1918-1919. An epidemic of “Spanish Flu” spread around the world. At least 20 million died, although some estimates put the final toll at 50 million. It’s estimated that between 20 per cent and 40 per cent of the entire world’s population became sick

The “Spanish flu” pandemic of 1918/19 was awful and it was terrible. The 1918H1N1, to give its proper name, has been estimated that it infected about a third of earth’s human population and killed about 50 million people. In Britain alone the virus was responsible for the death of about 250,000 people. The high death rate in healthy people, particularly those in the 20-40 year age group (often from a secondary infection), was a distinctive feature of this particular pandemic. The Daily Mirror reported that 65 soldiers had to be buried at sea from just one troopship before it arrived at Southampton. The global economy decreased by about 5 per cent.

Sometimes death came terrifyingly quickly with victims turning blue-black and drowning in their own body fluids. There were no influenza vaccines or antibiotics to treat secondary bacterial infections. It wasn’t proved that Influenza was caused by a virus until 1933.

When the outbreak started WW1 was still happening and there were wartime restrictions on helpful communication. The amount of infections and deaths were suppressed in many countries fighting in the war so as to maintain public morale. Spain, a neutral country, had no such restrictions and newspapers were allowed to openly report on the impact the flu was having. This meant the rest of the world thought the situation particularly bafd in Spain – hence the inaccurate name “Spanish Flu”. Historian John Barry, author of “The Great Influenza,” wrote that the US Congress passed a Sedition Act in May 1918, which made it a crime to “wilfully utter, print, write, or publish any disloyal, profane, scurrilous, or abusive language about the form of the Government of the United States.” That meant, whether they wanted to or not, the newspapers had to suppress any reports of the flu epidemic. It also meant, according to Barry, that “against this background, while influenza bled into American life, public health officials, determined to keep morale up, began to lie.” The huge movement of soldiers around the world contributed to the transmission of the H1N1 virus with a speed never before seen.

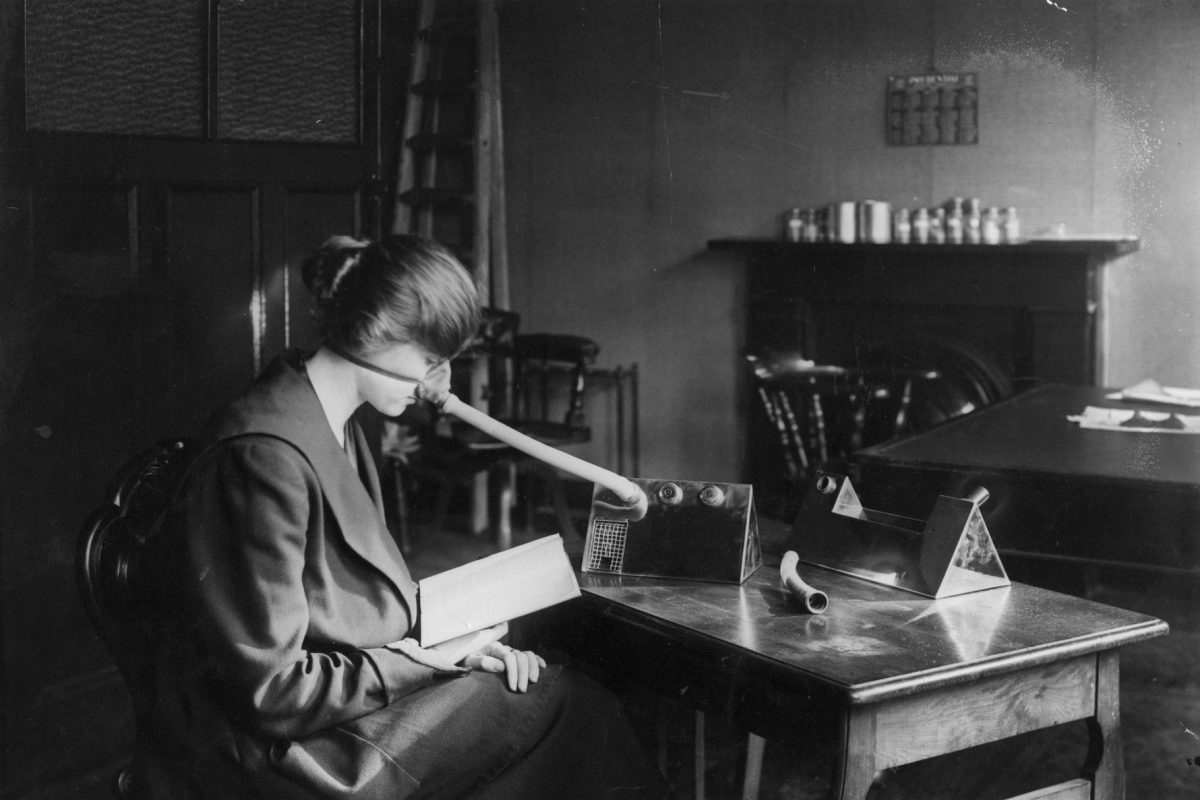

A public health worker carries a spray pump filled with cleaning spray for use on buses

In Britain the disease came in three separate waves. Relatively benign in the spring of 1918, ‘catastrophic’ at the end of the same year and a last moderate wave in the Spring of 1919. Ben McIntyre in the Times described the ‘patchy and muted’ British response of the time:

ome local authorities urged people who felt unwell to remain at home, keep handkerchiefs away from children, clean their teeth thoroughly and eat plenty of porridge. “Give up shaking hands for the present and give up kissing for all time,” one pamphlet urged. Many elementary schools were closed, but secondary schools remained open, as did cinemas and churches. Among the cures suggested were whisky, cigarettes and raw onions. Quacks offered such remedies as Dr Williams’ Pink Pills for Pale People.

The lack of wartime and post-wartime reporting of the flu outbreak meant that the memory of what happened almost disappeared. There are no memorials commemorating the deaths caused by Spanish Flu although it caused far more than the shells, tanks, bombs and bullets on the battlefields of France and elsewhere. In an article in the Daily Mirror published in March 1919 and headlined “WHY “FLU” STILL DEFEATS THE DOCTORS. “M.D.” – “When will nations realise that lice, rats, mosquitoes and fleas are deadlier “weapons” against human life than any machine gun or cloud of poison gas?”

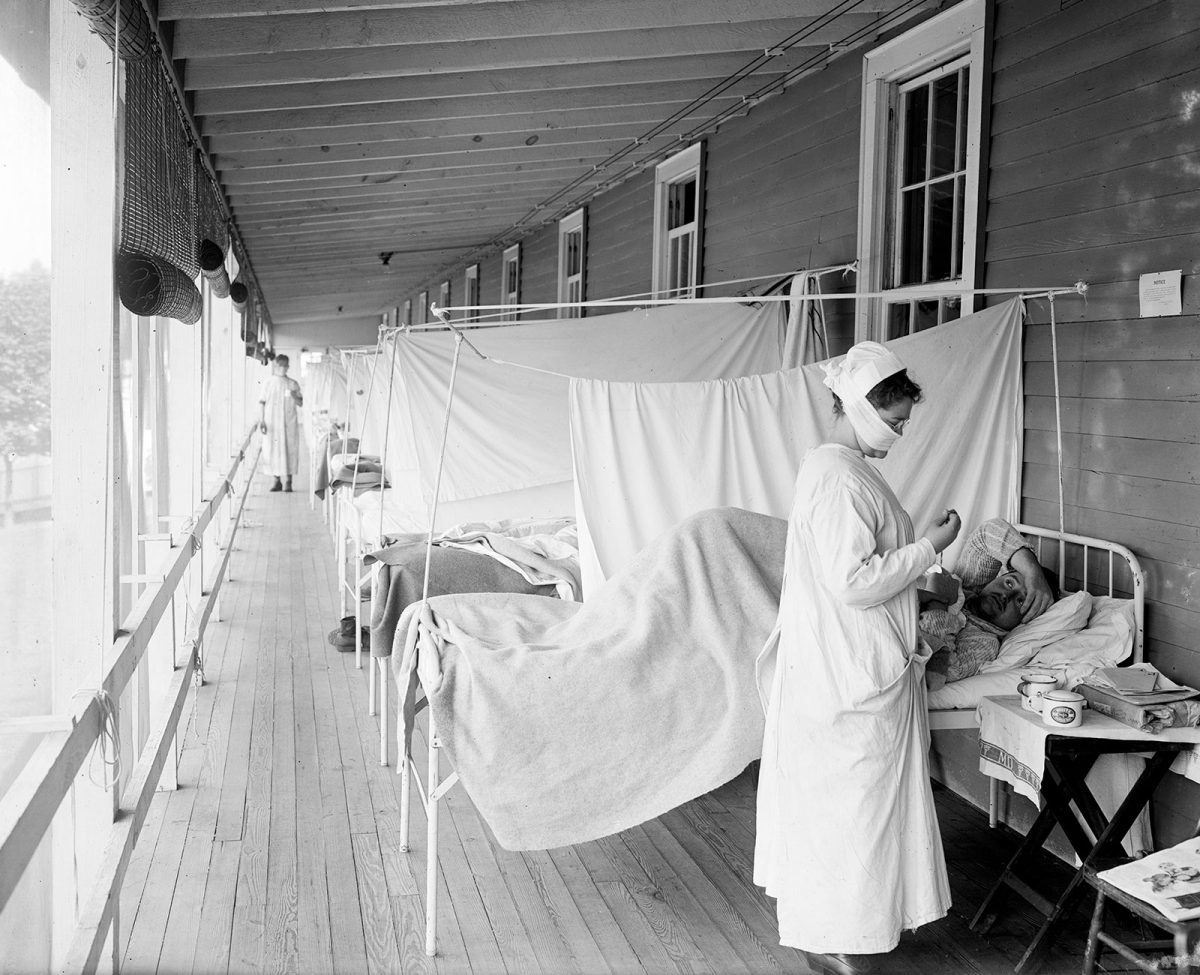

Walter Reed Hospital The influenza ward at Walter Reed Hospital, Washington, D.C., during the 1918–19 epidemic.

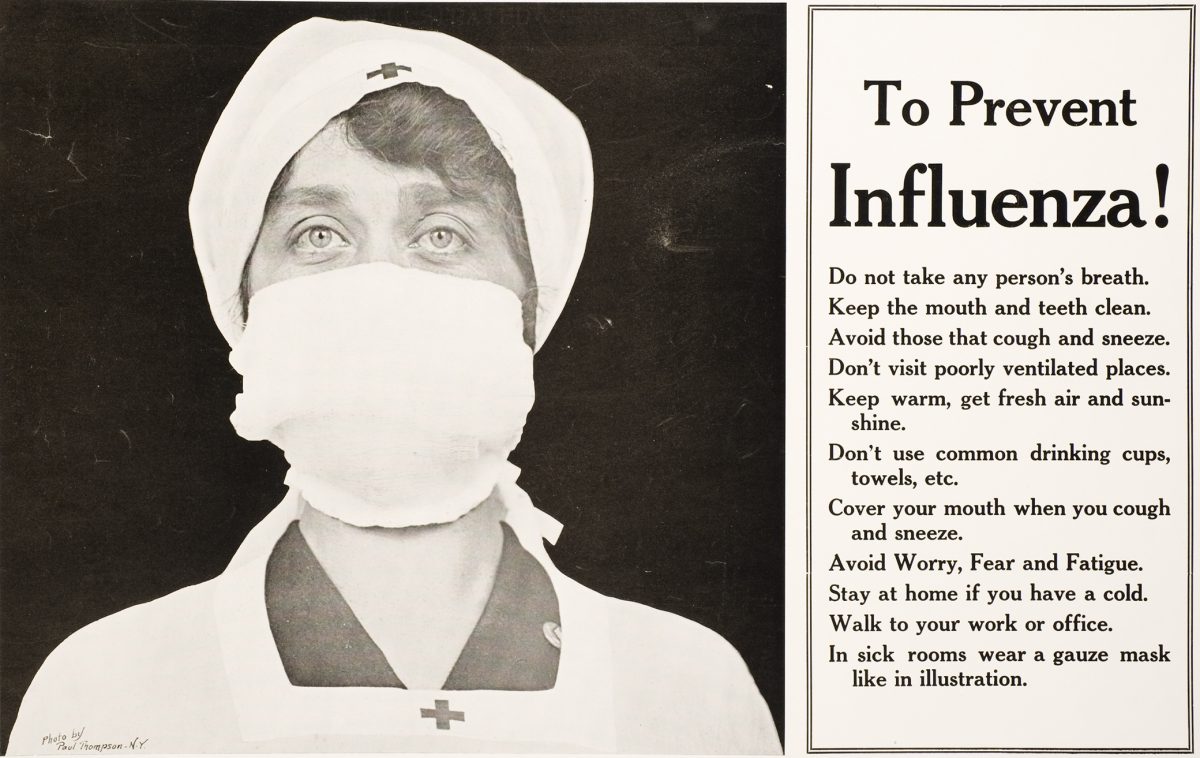

“To Prevent Influenza!” poster, from Illustrated Current News, 1918.

A man sprays the floor of an open top bus with an “anti-flu spray”. Public transport was suspected of spreading disease

St. Louis Red Cross Motor Corps workers and ambulances waiting to receive influenza patients in 1918

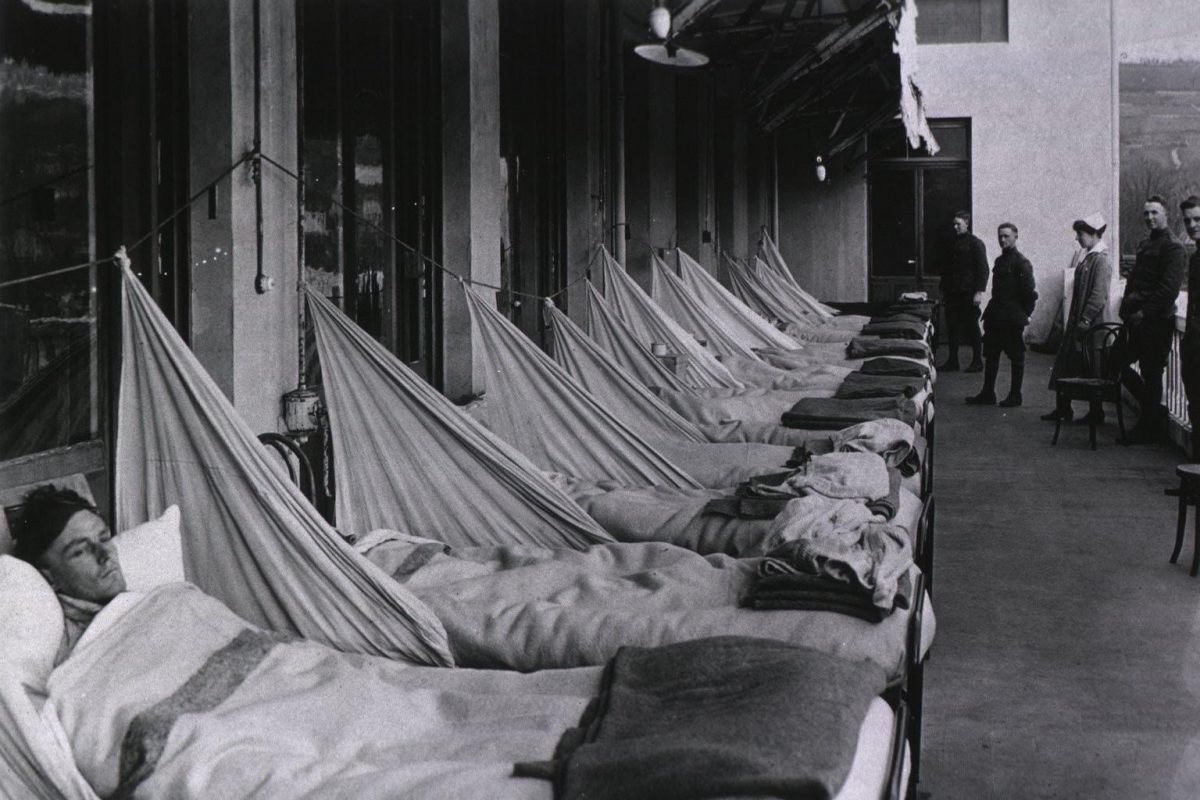

An emergency hospital in Kansas during the 1918 influenza epidemic

A New York city street sweeper wearing a mask during the 1918 influenza epidemic.

1918-1919. An epidemic of “Spanish Flu” spread around the world. At least 20 million died, although some estimates put the final toll at 50 million. It’s estimated that between 20 per cent and 40 per cent of the entire world’s population became sick

A Red Cross demonstration in Washington during the influenza pandemic of 1918

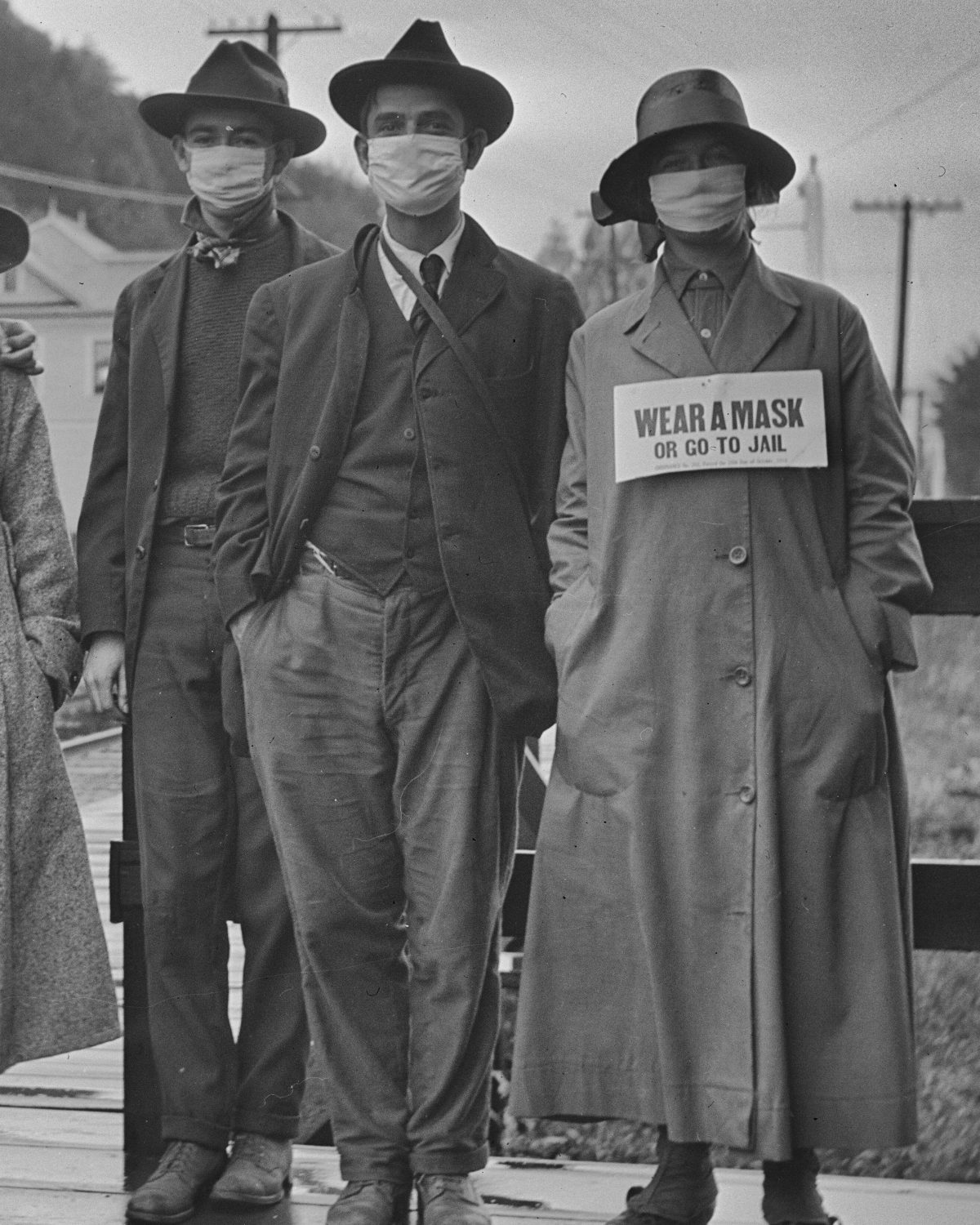

wear a mask or go to jail

mask wearing on a trolley bus

A woman social distancing while wearing a flu mask during the 1918-1919 flu pandemic.

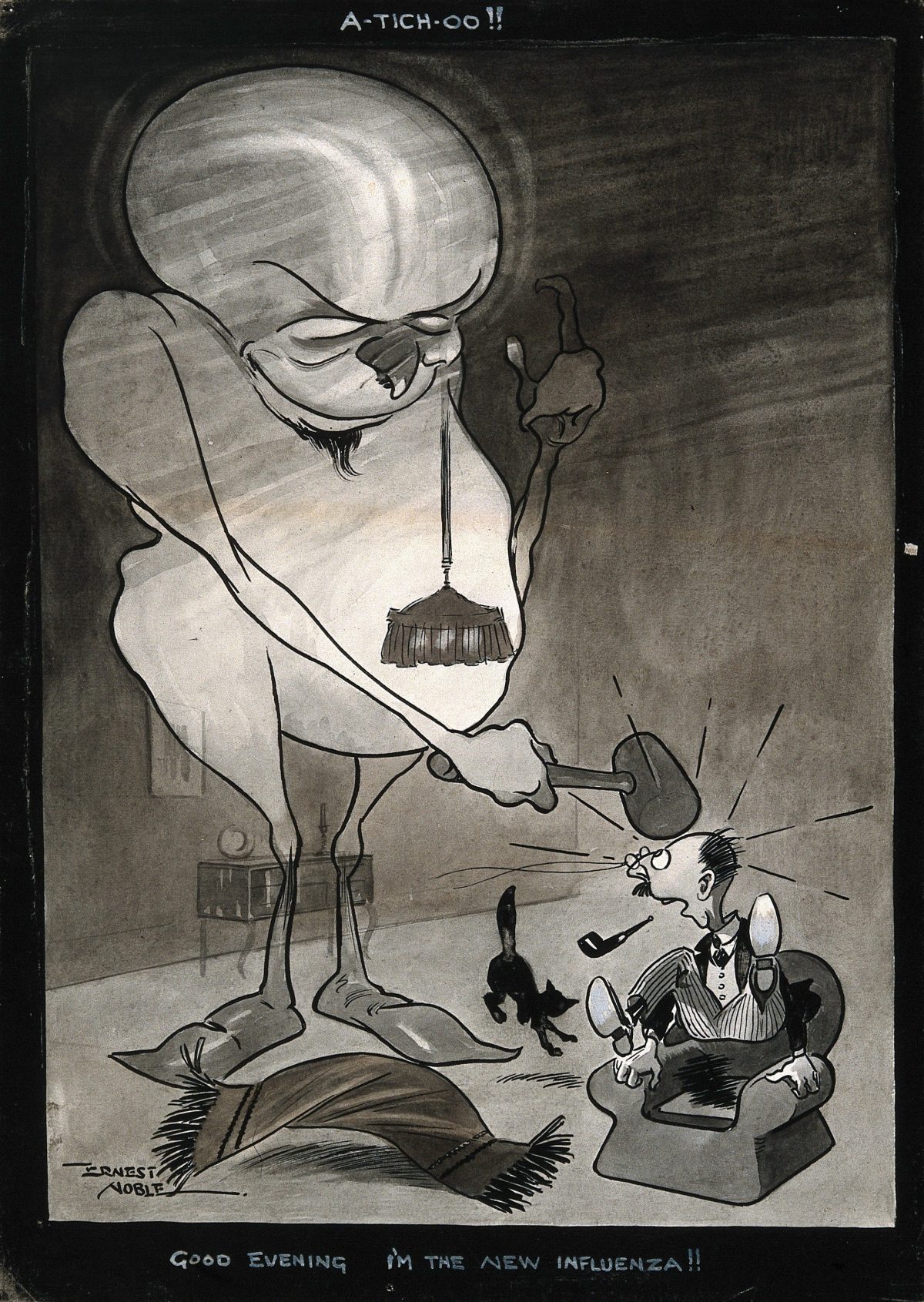

Poster illustrating new flu epidemic

People wait in line to get flu masks on Montgomery Street in San Francisco in 1918. (Hamilton Henry Dobbin

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.