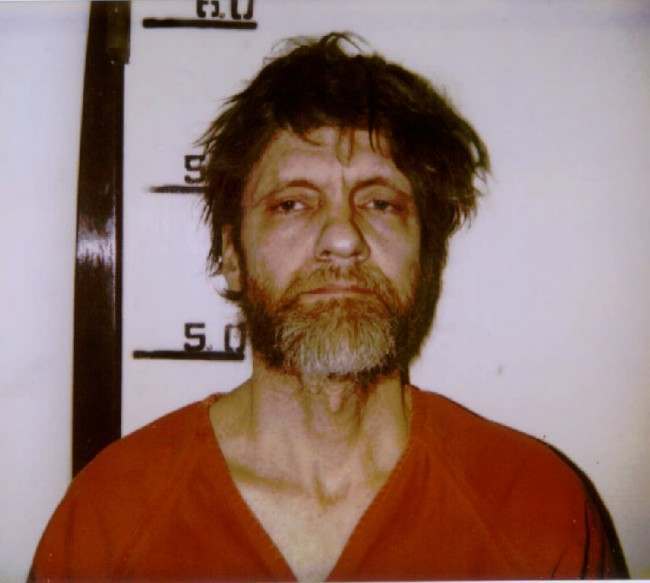

ON May 3 1996, Theodore John Kaczynski, 53, had his mug shot taken by7 the Lewis and Clark County Jail in Helena, Montana. Kaczynski had been taken into custody at his mountain cabin north of Helena as a suspect in the Unabomber bombing spree.

The man called the “Unabomber” had killed three people and maimed 23 others with parcel bombs. His first known device exploded in 1978 and the last, killing California Forestry Association president Gilbert Murray. His campaign had continued to his most recent bomb in 1995. His final bombs was his 16th.

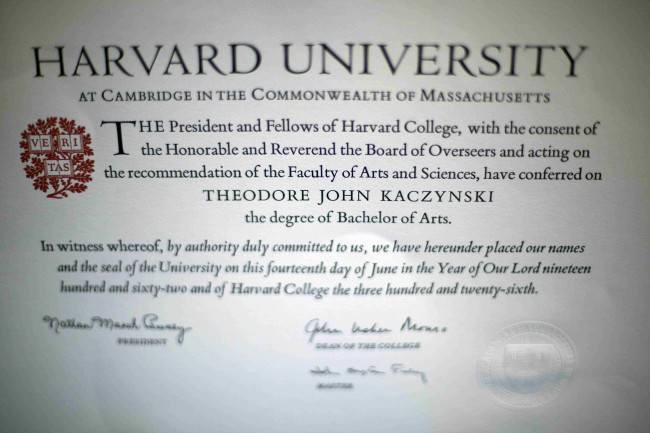

Kaczynski, a Harvard graduate with doctorate from the University of Michigan, had taught mathematics at the University of California at Berkeley. Police had long suspected the bomber was an educated man. The “Una” of his nickname was rooted in his chosen targets – universities and airlines.

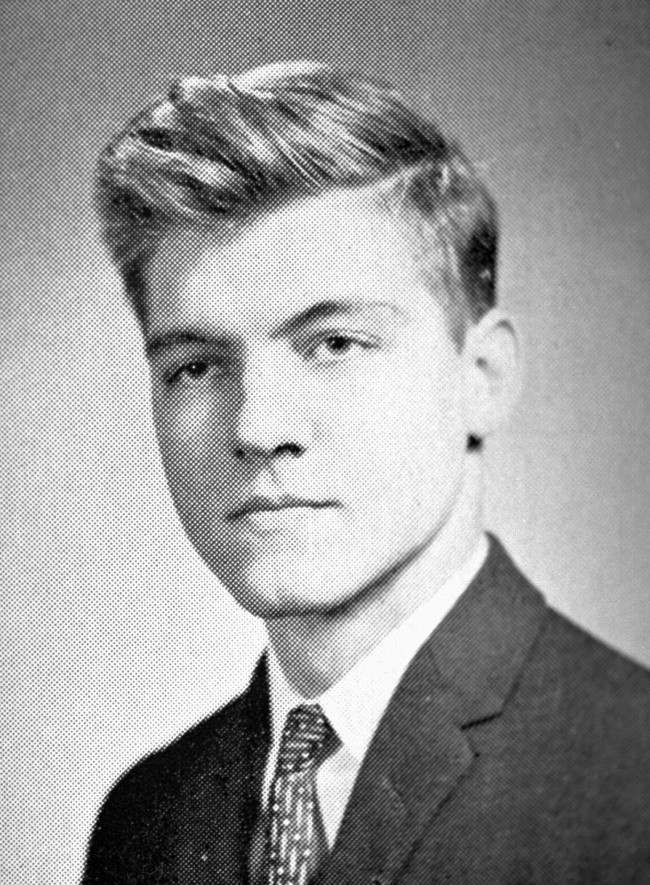

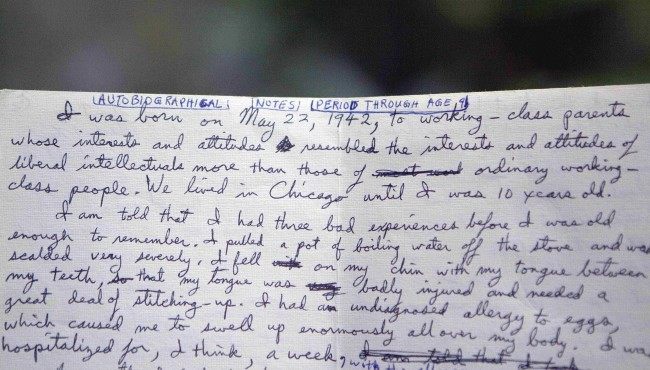

A member of the Unabom task force, demanding anonymity, has told The Associated Press that Ted John Kaczynski, shown in this image from a 1962 Harvard yearbook, has been named a possible suspect in the Unabomber killings. Family members turned the former Berkeley professor in to the FBI, and federal agents began searching his Montana home Wednesday, April 3, 1996, law enforcement officials said.

He was thought to be motivated by hatred of the capitalist system and technological advances.

A neighbour of Mr Kaczynski home in Lolo National Forest, Montana, was Dick Lundberg. He told media after the arrest:

“He kept to himself, never bothered anyone. He never did say anything bad about anybody. We thought he was all right.”

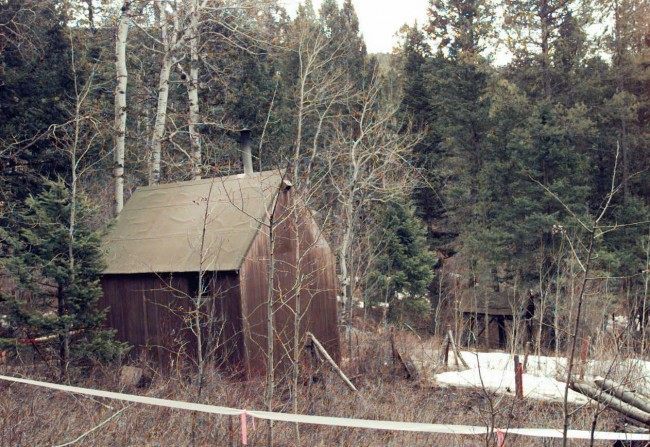

The cabin of suspected Unabomber Theodore Kaczynski, partially surrounded by white, plastic tape, sits at the end of a muddy, private road, hidden in a wooded setting about 300 yards from the nearest neighbor Saturday, April 6, 1996 in Lincoln, Mont. The home, on 1.4 acres, is only 10 by 12 feet, with no electricity or plumbing. Date: 06/04/1996

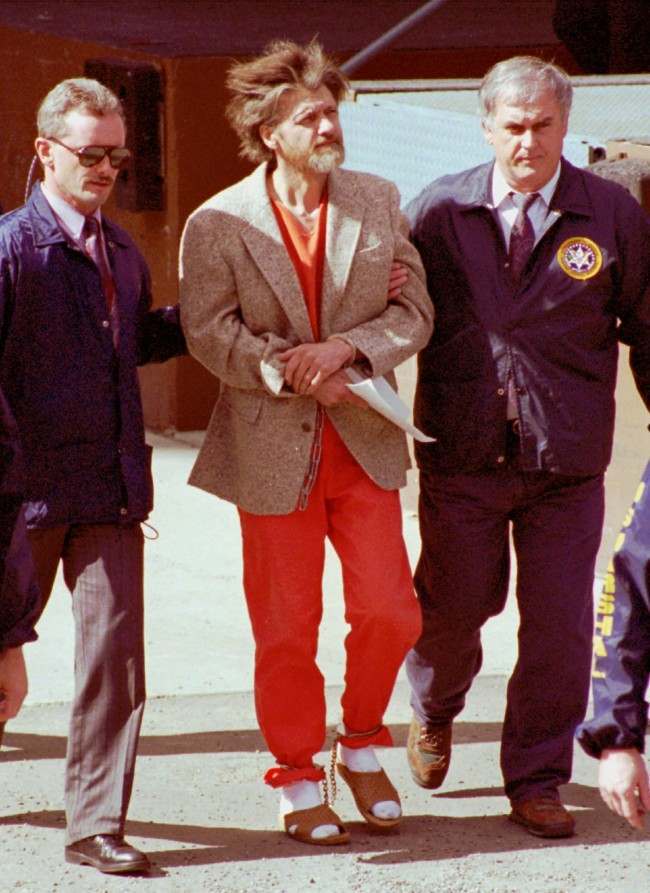

Wearing a sport coat over his jail coveralls, Theodore John Kaczynski is escorted in handcuffs and ankle shackles by two unidentified federal agents as they leave the federal courthouse in Helena, Mont., Thursday, April 4, 1996. Federal agents found a partially assembled bomb in the mountain shack of the former Berkeley math professor suspected of being the Unabomber.

A tip-off from members of Theodore Kaczynski’s own family is said to have led to his arrest.

At the family home in Chicago they discovered notes by Mr Kaczynski which were strikingly similar to the Unabomber’s “manifesto” published by the Washington Post and New York Times newspapers last year. (More on that below.)

His younger brother David, who had first contacted the police, received a $1m reward.

He said he would use the money to help the Unabomber’s victims.

David Kaczynski, the brother of Unabomber Theodore Kaczynski, listens to a question before his talk on Tuesday, March 28, 2006, in Albany, N.Y., at the Center for Disability Services. Ten years after Theodore Kaczynski’s arrest, the once-friendly brothers are worlds apart. One is in prison for life. The other talks to crowds as an anti-death penalty lobbyist and offers a picture of his infamous brother as a human being suffering from mental illness. Date: 28/03/2006

In 1998, he pleaded guilty to being the Unabomber.

In May 1998 Theodore Kaczynski was sentenced to life imprisonment without parole.

Unabomber Theodore Kaczynski is shown in police custody while entering a federal courthouse in Helena, Mont., in this June 21, 1996 file photo.

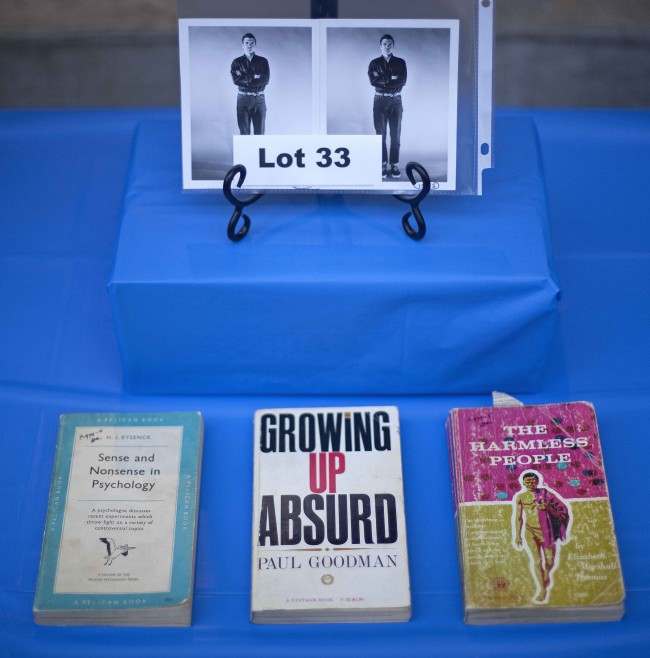

On July 21, 2005, a federal appeals court ordered the government to sell Kaczynski’s writings and other materials the authorities seized in 1996 from his Montana cabin and use the proceeds to pay restitution to his victims.

The cabin went on sale. It was yours for $69,500.

Workers move the cabin that Unabomber Theodore Kaczynski lived in, out of a storage facility in Rancho Cordova, Calif., Thursday, May 1,2003. The cabin was to be dismantled and moved to another location, but a last minute change of plans stopped the razing. The cabin, built by Kaczynski in Monatana, was trucked to Rancho Cordova, a suburb of Sacramento, in December of 1997 by the federal defenders office. The cabin was stored by a company that specializes in the secure storage of critical evidence and sensitive material.

Date: 01/05/2003

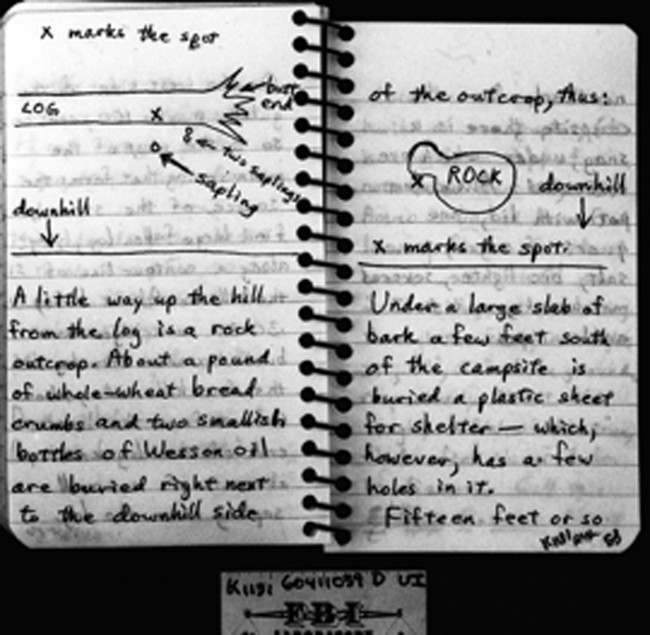

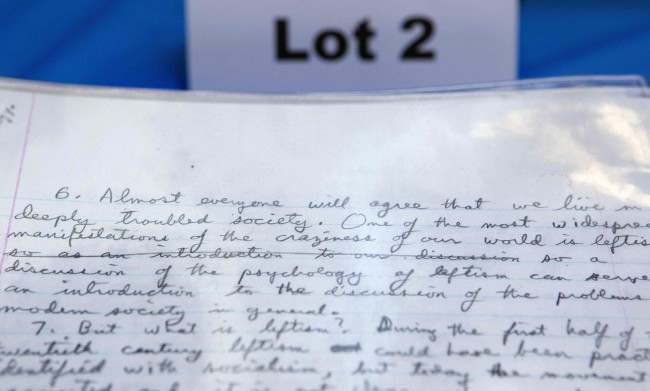

Other times for sale: a notebook:

His hoodie and sunglasses.

And:

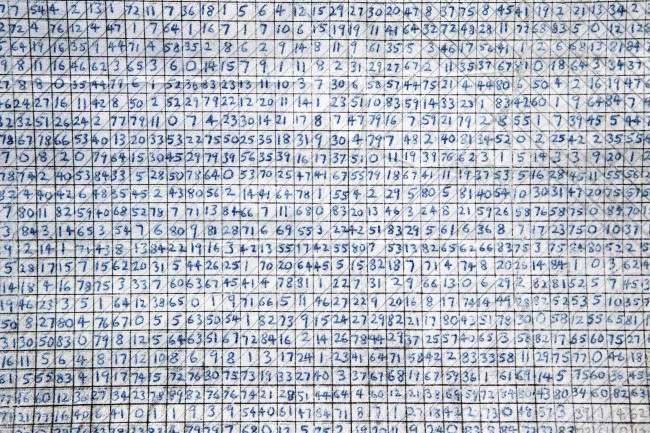

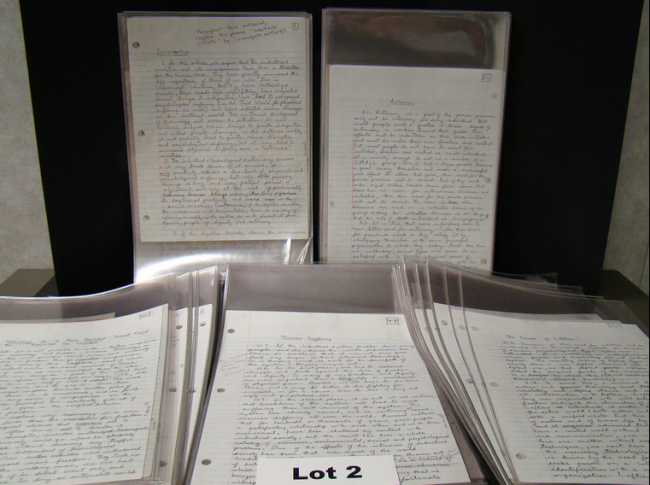

The handwritten manifesto

The handwritten manifesto

You could read his diaries, musing on such lines as:

“Experiment 97. Dec. 11, 1985. I planted bomb disguised to look like scrap of lumber behind Rentech Compute store in Sacramento. … The device was hidden inside a hollow piece of wood, so that when the wood were to be grabbed or picked up, the bolts in the trigger would come out. The device was deployed on December 11th, 1985.”…

“In some of my notes I mentioned a plan for revenge on society. Plan was to blow up an airline in flight. Late summer and early autumn I constructed device. Much expense, because had to go to Gr. Falls to buy materials.”…

“Last fall I attempted a bombing and spent nearly three hundred bucks just for travel expenses, motel, clothing for disguise, etc. Aside for cost of materials for bomb. And then the things failed to explode. Damn, this was the firebomb found in U. of Utah business school outside of room containing some computer stuff.”…

The lots raised a total of $232,246.

Was that his only legacy? Aside from the graves and wounds, some have repatriated the killer.

The New York Times’ William Glaberson profiled the man:

…the half-mythic Unabomber was one thing. The man charged with his crimes, Theodore Kaczynski, is something else entirely. For starters, he tried to hang himself with his underwear, accelerating a metamorphosis from anti-technology crusader to bad joke.

“There is an immunity that comes from being unknown,” said Todd Gitlin, a professor of culture, journalism and sociology at New York University. “Then all these myths can be projected onto him: He’s the motivated runaway who is hiding from the wicked world, the loner, ‘Who is that masked man?”‘

But as the public lens has focused on the real defendant who replaced the rakish Unabomber portrayed in the famous FBI sketch, the popular image has degenerated into material for Jay Leno and water-cooler comics. In many of the jokes, the Unabomber seems “pathetic more than evil,” said Professor Gitlin.

It may be that the humor comes from a deep fear of the harm that a disturbed criminal can do. “There is something that is very difficult for society to confront, and that is that crazy people have the means to do damage,” Professor Gitlin said. “If you think of him as a joke, then you don’t have to confront that: He has become shtick.”

Did the Unabomber become a star?

In 2013, Jenna Wortham wrote:

Now that I’m back and mostly recovered from South by Southwest, my friends, editors and fellow reporters keep asking me about the most interesting thing I saw in Austin.

Some things I have already written about.

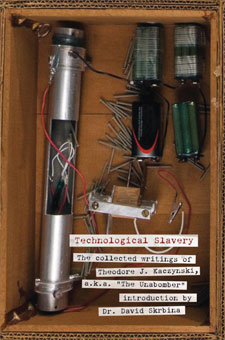

Others, I haven’t been able to get out of my mind, like the chat I had with David Skrbina, a professor at the University of Michigan-Dearborn…

Mr. Skrbina was in Austin to debate the merits of technology, and you can guess which side he came down on. He thinks we would be better off without any of it, and has no interest in exploring reasons we might need more of it…

Mr. Skrbina was heavily influenced by the lengthy manifesto written in 1995 by Ted Kaczynski, the Unabomber, which cast doubt on the benefits of technology and raised questions about unforeseen consequences of technology in modern society. Mr. Skrbina, began corresponding with Mr. Kaczynski, and helped to publish a collection of essays a few years ago. But he is quick to say that he does not condone or endorse the violent actions of Mr. Kaczynski.

“But just because he is a criminal doesn’t mean he’s not a rational, intelligent, thinker,” Mr. Skrbina said. He is a firm believer in Mr. Kaczynski’s principles, and Mr. Skrbina’s two daughters grew up calling the Unabomber Uncle Ted.

Mr. Skrbina says that many modern ailments and conditions — attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, depression and aggravated stress — are the direct result of cognitive difficulties exacerbated by the influence of technology. ”We aren’t evolved to live that highly interactive of a lifestyle,” he said. “We don’t adapt well to it.”

You kill a few people and your screed become worth reading and repeating?

The University of Colorado hosted a panel titled “The Unabomber Had a Point”.

And we can all know the Unabomber’s words because on Sep 19, 1995, The Washington Post and New York Times agreed to publish a 35,000-word manuscript submitted by the Unabomber, who had promised to halt his attacks if either newspaper ran his lengthy critique of industrial society.

The papers’ publishers issued a joint statement:

Statement by Donald E. Graham and Arthur O. Sulzberger Jr:

For three months The Washington Post and The New York Times have jointly faced the demand of a person known as the Unabomber that we publish a manuscript of about 35,000 words. If we failed to do so, the author of this document threatened to send a bomb to an unspecified destination “with intent to kill.”

From the beginning, the two newspapers have consulted closely on the issue of whether to publish under the threat of violence. We have also consulted law enforcement officials. Both the Attorney General and the director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation have now recommended that we print this document for public safety reasons, and we have agreed to do so.

Therefore, copies of the Unabomber’s unaltered manuscript are being distributed in today’s Washington Post. The decision to print was made jointly by the two newspapers, and we will split the costs of publishing. It is being printed in The Post, which has the mechanical ability to distribute a separate section in all copies of its daily paper.

You can read it in full here.

In 2011, Dr Keith Albow wrote on Fox News:

Was the Unabomber correct?

Kaczynski’s ideas, described in a manifesto entitled, “Industrial Society and Its Future,” cannot be dismissed, and are increasingly important as our society hurtles toward individual disempowerment at the hands of technology and political forces that erode autonomy.

So. What to make of the killer, who wrote before his bombing began:

I intend to start killing people. If I am successful at this, it is possible that, when I am caught (not alive, I fervently hope!) there will be some speculation in the news media as to my motives for killing…. If some speculation occurs, they are bound to make me out to be a sickie, and to ascribe to me motives of a sordid or “sick” type. Of course, the term “sick” in such a context represents a value judgment…. the news media may have something to say about me when I am killed or caught. And they are bound to try to analyse my psychology and depict me as “sick.” This powerful bias should be borne [in mind] in reading any attempts to analyse my psychology.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.