Sir Christopher Wren

Said, ‘I am going to dine with some men.

If anyone calls

Say I am designing St. Paul’s.’

– Edmund Clerihew Bentley, 1905.

In the early hours of Sunday 2nd September 1666, fire took hold at the house of Thomas Farynor, King Charles II’s baker on Pudding Lane, not far from London Bridge. A workman smelt smoke and sounded the alarm. Farrynor, his wife, daughter and one servant, crawled through an upstairs window and fled across the rooftops. They left behind the maid, who was by a popular account too scared to move. Thus she became the Great Fire of London’s first victim.

Of course, to begin this was just a small fire. Sir Thomas Bloodworth saw the flames and stated, “A woman might piss it out.”

History proves him wrong.

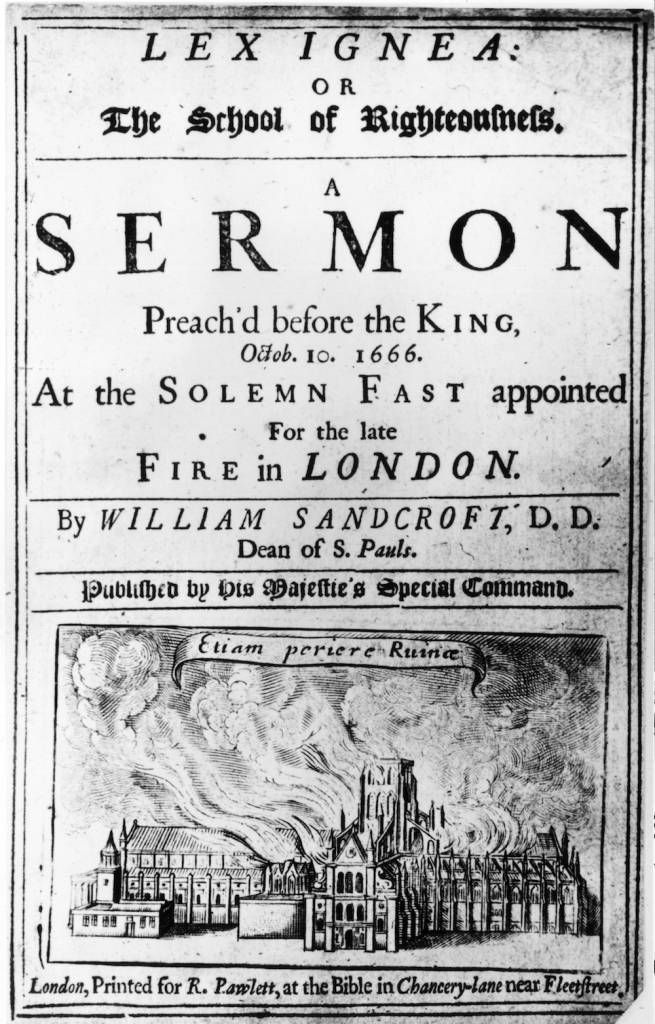

October 1666, A pamphlet announcing a sermon to be preached by William Sandcroft DD (Doctor of Divinity) Dean of St Paul’s on 10th October 1666 in the presence of the King, to remember the Great Fire of London.

One spark and all would be gone. But the baker was adamant that he’d put out the fires in his overs before retiring to bed. A Parliamentary Committee convened to debate the fire’s cause. The King declared it an act of God. But a French Protestant called Robert Hubert confessed. He and 23 conspirators had started it deliberately, he said. The Earl of Clarendon commented: “Neither the judges, nor any present at the trial did believe him guilty; but that he was a poor distracted wretch, weary of his life, and chose to part with it.” He was helped by a jury – that included three Farynors – and was hanged at Tyburn,” notes Robinson, who has more:

The Parliamentary committee reported in January 1667 that ‘nothing hath yet been found to argue it to have been other than the hand of God upon us, a great wind, and the season so very dry’. Yet with Farynor declaring – as expected – that his ovens had been completely extinguished on the night in question, the committee was as widely believed as the Warren Report, and the cause of the fire became the grassy knoll of late seventeenth century conspiracy theorists. In 1678, during the Popish Plot, Titus Oates declared that Jesuit priests were to set fire to the city, prompting a Commons resolution declaring that ‘the City of London was burnt in the year 1666 by the Papists… to introduce arbitrary power and Popery into this Kingdom’. In 1685 the Duke of Monmouth, rebelling against the new King, the Catholic James II, accused him of deliberately starting the fire. It was not until 1831 that the inscription on the fire’s commemorative Monument, blaming ‘the treachery and malice of the Popish faction’, was removed. An inferno caused by a forgetful baker, fuelled by a strong wind and indecisive leadership, was blamed on Catholics for over 150 years.

So much for the mob and rule of law. What of the fire in a cramped city of fetid air and filth? The dirty air and that had spread the Black Death in 1665 now accelerated the flames. Plague killed one in every five Londoners . One year before fire raged a mortality bill dated 9–26 September 1665 recorded the deaths of 7,165 people from the Great Plague.

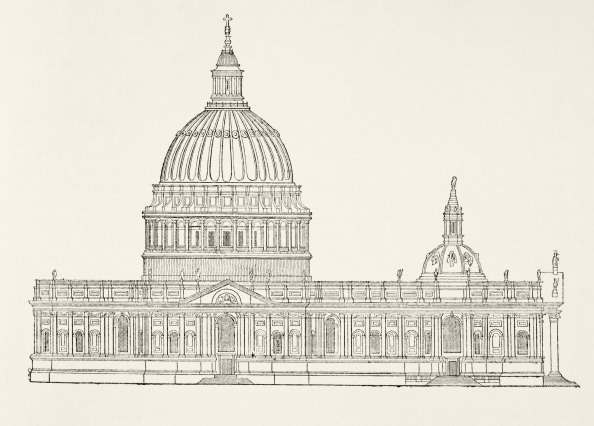

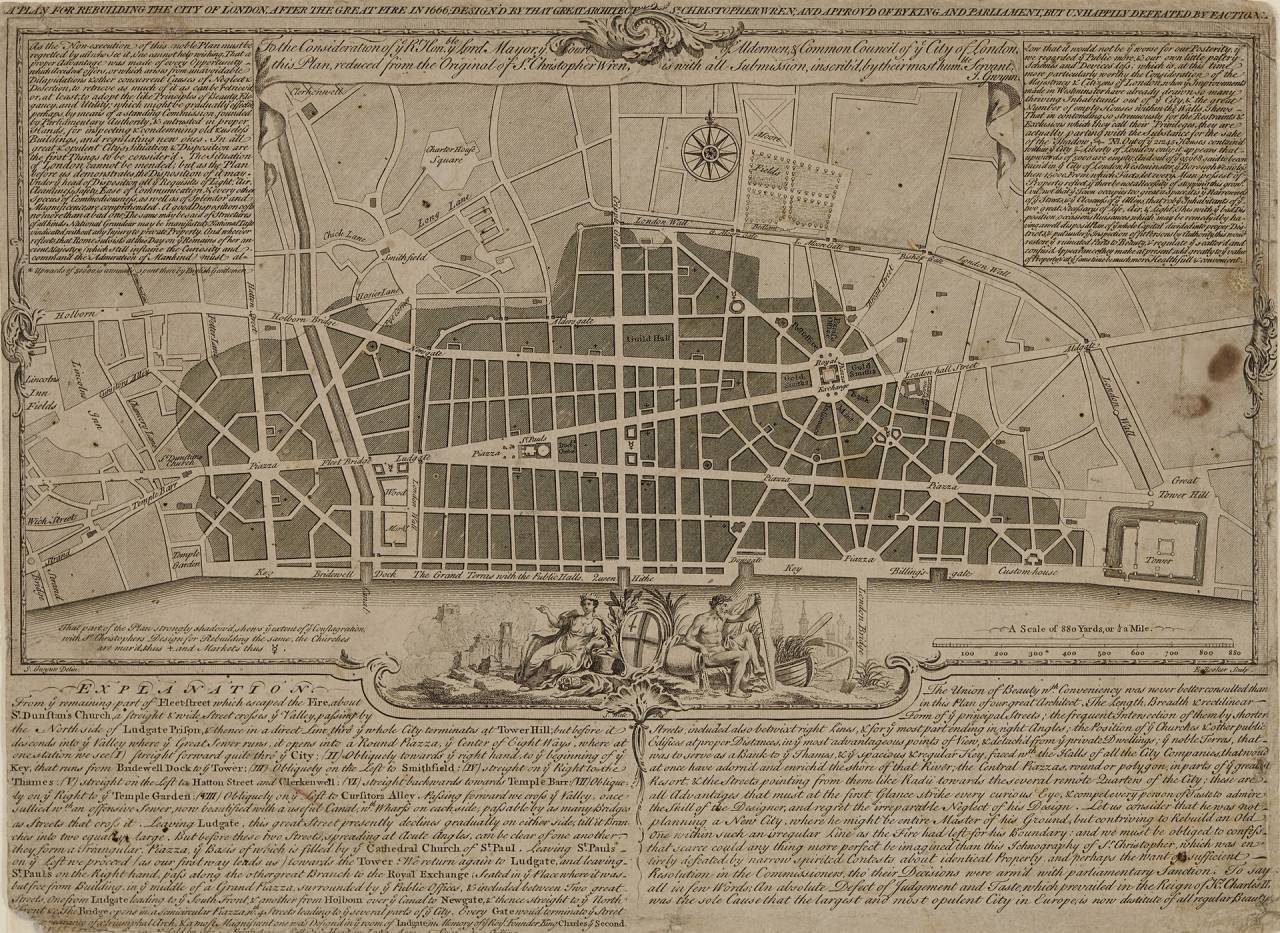

Was this fire Heaven sent, as Charles had stated? Did the fire purge the city it seared? By Thursday, the fire was almost out. Over 13,000 houses were gutted, leaving 100,000 people homeless. Five-sixths of the walled area of the city had been destroyed. One leading architect, Sir Christopher Wren, saw opportunity in the ashes. He envisaged a new London, a city of wide avenues and open spaces.

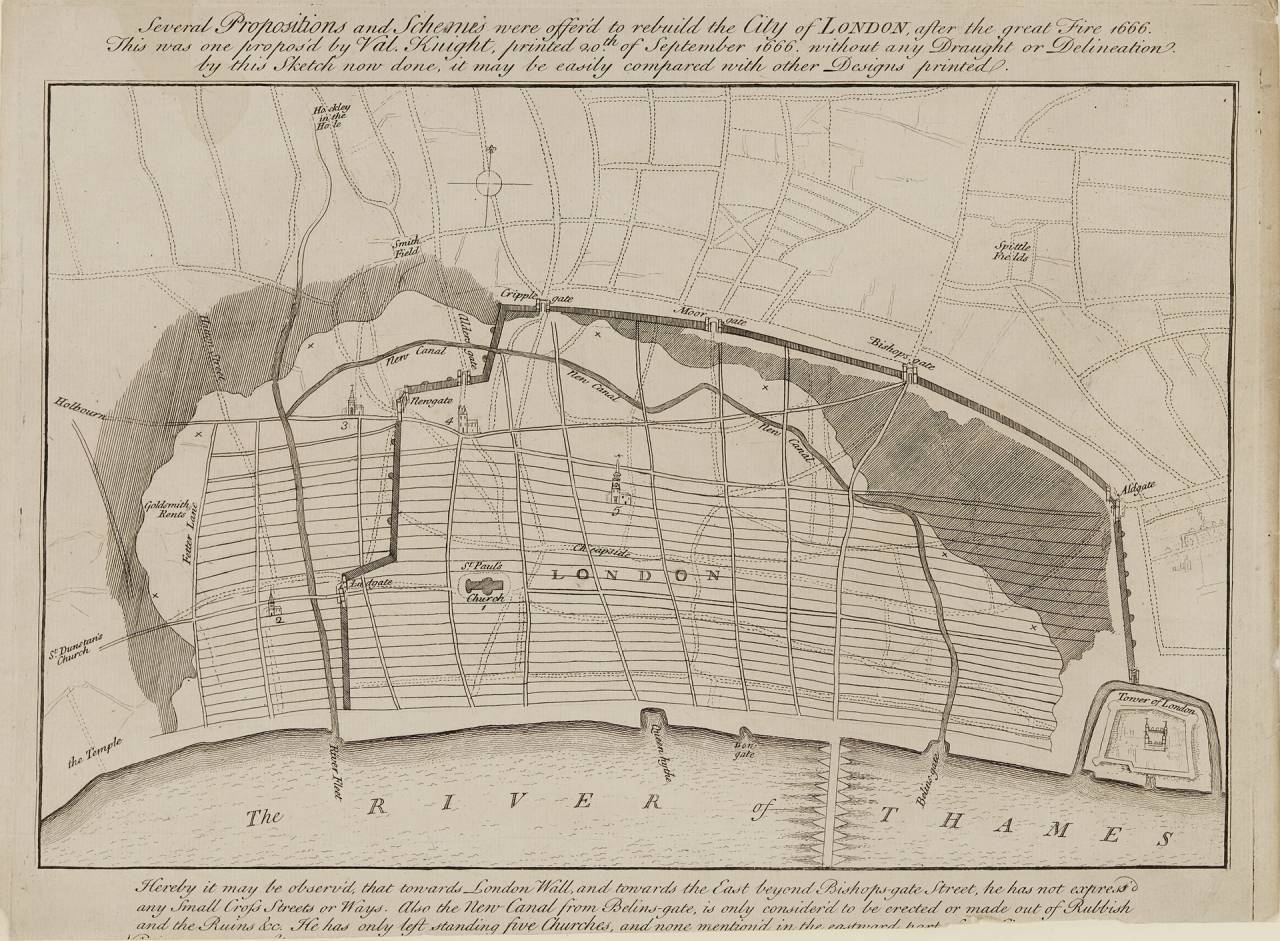

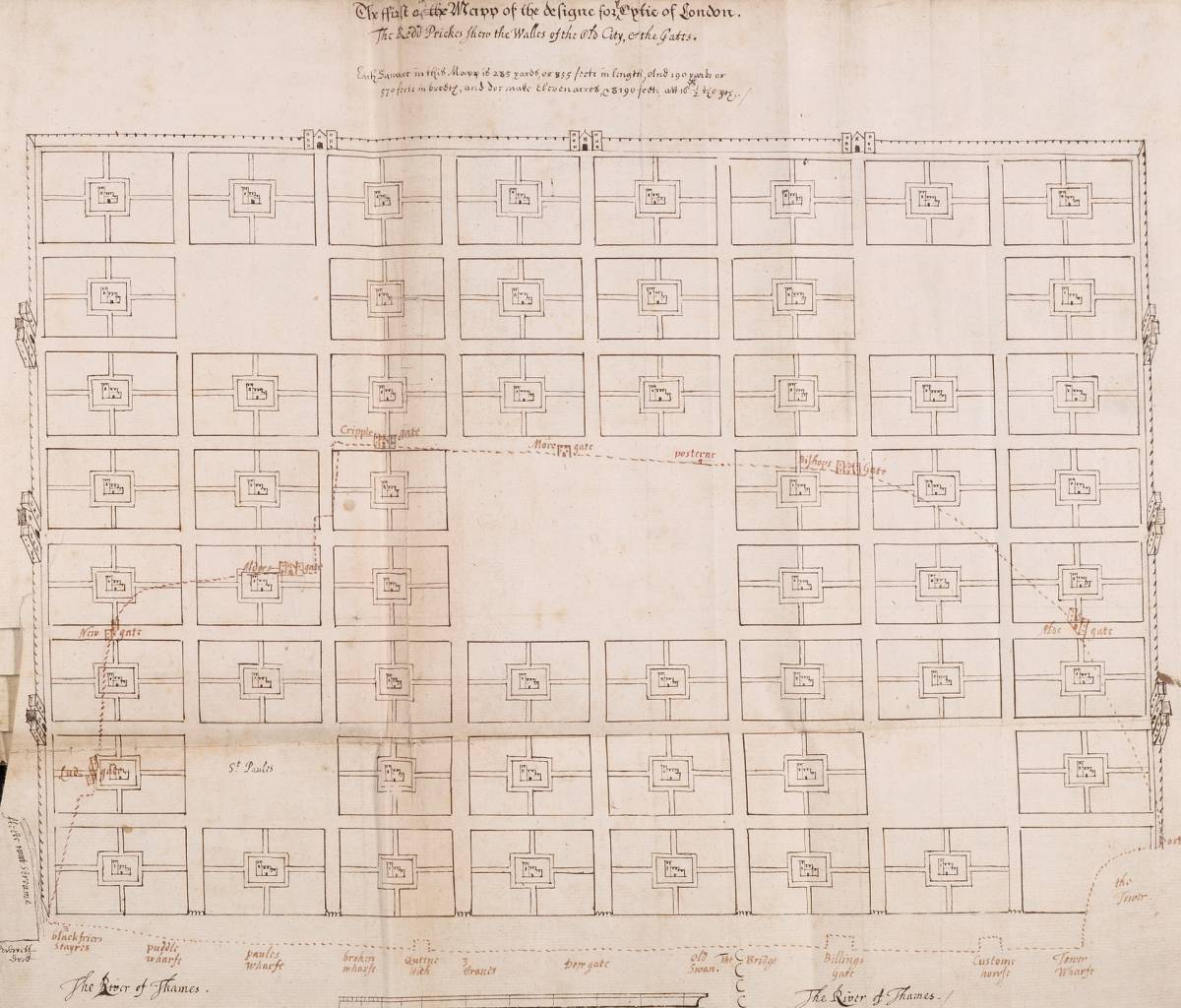

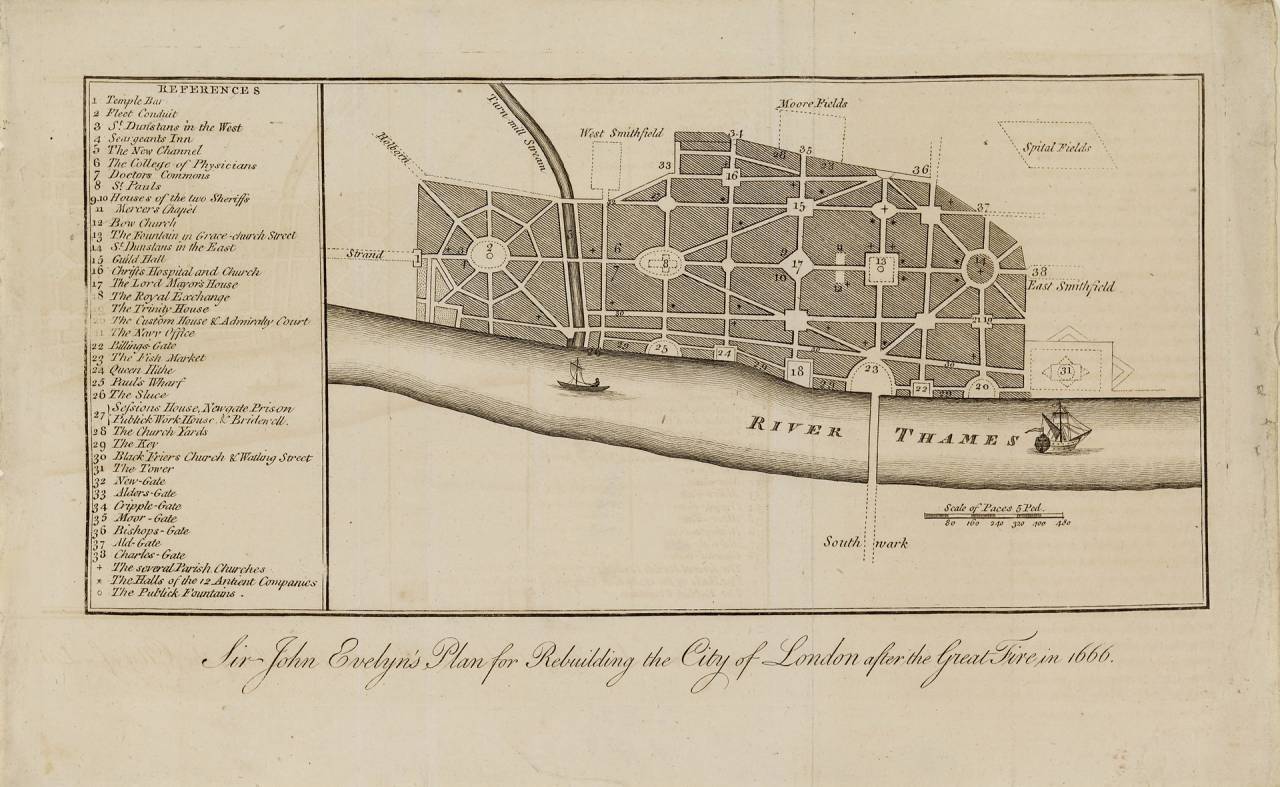

Other visionaries produced their masterplans for London, a place to match Charles II call for “a much more beautiful city than is at this time consumed… of such breadth as may with God’s blessing prevent the mischief that one side may suffer if the other be on fire.”

Blessedly, no single architect was commissioned to design a moribund city of order and uniformity, preventing it from becoming a dull museum piece like Georges-Eugene Haussmann’s Paris. Rules were set on the height of buildings and a movements away from wood exteriors. But London’s haphazard sprawl remained.

Below are five designs for the new London, each a composite blend of its time and the architect’s ego and dream. Wren got the biggest job, redesigning the ruined St Paul’s. Tourists and Londoners visiting the beautiful Cathedral can arrive via the wide expanses of Cannon Street and Cheapside. Or if they want to wend their way, they can nip down this and that lane, meandering through the city’s higgledy-piggledy pockets of life. Do that. It’s much better. If you’re lucky, you might even get lost.

‘Well-respected in royal circles’- scientist Robert Hooke’s plan. Illustration- London Metropolitan Archives, City of London

‘Wide boulevards and grand civic spaces’- Christopher Wren’s plan to rebuild London. Illustration- RIBA

See Creation from Catastrophe at the Riba Architecture Gallery.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.