Imperial Wizard H.W. Evans

By 1924, the Ku Klux Klan had reached its peak historical membership, with estimated numbers in the millions. “Its numbers dropped to about 350,000 three years later,” writes Eric Herschthal in a review of two recent histories. While sex scandals and embezzlement among the “invisible empire”’s leaders are often cited for the precipitous drop, historians argue that what really set them back was too much success.

In the years of the so-called “second coming” of the Klan after the release of D.W. Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation in 1915, “the Klan so thoroughly baked its all-encompassing racism into mainstream society that it had nothing else to do.”

It played a pivotal role in the Immigration Act of 1924, which drastically cut the number of Jewish immigrants, and excluded Asian immigrants entirely. It’s lobbying on behalf of eugenics led to sterilization laws in thirty states, which disproportionately targeted poor and black women. And at the local level, the Klan got school districts throughout the country to prohibit any textbook that “speaks slightly of the founders.”

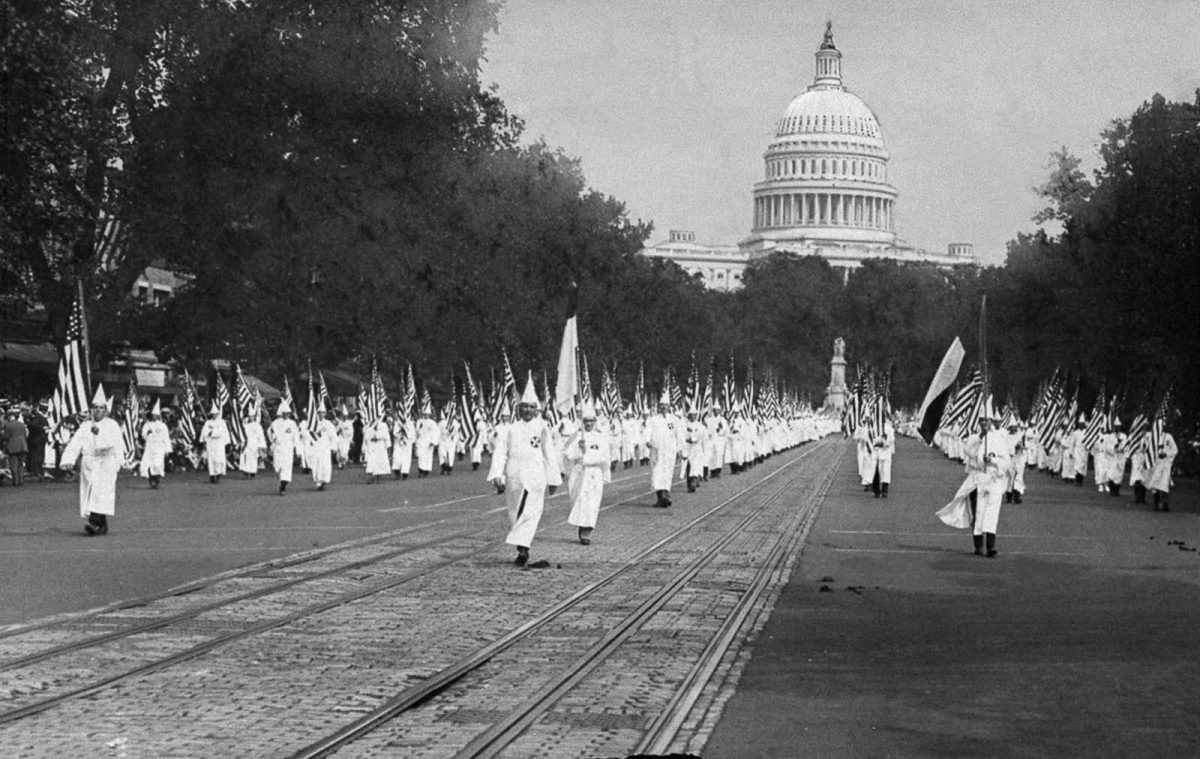

The huge August 8, 1925 Klan march on Washington—which saw over 50,000 members in full regalia take over the streets of the U.S. capital city—was as much a victory celebration as a recruitment effort.

The Chicago Herald described the scene at the time: “state and county delegations of the order trooped along in the plain robe and hoods” lead by “kleagles, dragons, and other dignitaries of the organization in green silken robes and hoods, flaming red, bright yellow, and red, white, and blue” along with “companies of Klan guards in snappy uniforms, white caps, black Sam Browne belts, and black puttees.” It’s estimated that the march drew around 150,000 spectators.

Marchers saw little reason to hide their faces. In part, this was because the parade was only sanctioned if they marched unmasked. “But a mask was not really necessary,” notes Joshua Rothman at The Atlantic. The organization had members and defenders at every level of government. Their advocacy of “true Americanism” through forms of ethnic cleansing like eugenics and immigration bans had made them palatable to the public.

The Herald’s awed coverage was typical. “Tabloids covered the group incessantly,” Herschthal writes. “Pulp novelists made hooded Klansmen central characters in works of fiction; newspapers reported on its youth basketball and baseball teams. Even when the Klan was condemned, which was often…. The public was forced to debate the group’s merits.” Given multiple platforms from which to disseminate their rebranded message—one that was anti-worker, anti-urban, anti-Catholic, and anti-immigration as well as anti-black—their “particular brand of racism became ‘sanitized and normalized.’”

Rothman describes the organization’s largely overlooked influence on American life:

The Klan sponsored parades and picnics, baseball teams and beautiful-baby contests. Klansmen had musical troupes that performed public concerts and bands that played at state fairs. It had extensive women’s auxiliaries and even a number of auxiliaries for children, which had names such as the Junior Ku Klux Klan, the Tri-K Klub, and the Ku Klux Kiddies.

Fierce efforts to condemn and combat the Klan contributed to the publicity and galvanized their wide base of support, motivating those who shared their beliefs to become more politically active in response to the supposed threats of Civil Rights. By 1925, When the KKK marched unmasked through Washington, DC, “American values” had become synonymous and inseparable from Klan values.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.