In 1920, the 18th Amendment was passed making the manufacture and sale of alcohol illegal. But many people in this time of ‘Prohibition’ continued to drink and gangsters made enormous amounts of money from supplying illegal liquor.

In early 1933, Congress adopted a resolution proposing a 21st Amendment to the Constitution that would repeal the 18th. It was ratified by the end of that year, bringing the Prohibition era to a close.

What happened and why?

Beer barrels are destroyed by prohibition agents in an unknown location.

Picture date: Jan. 16, 1920.(AP-PHOTO)

Ref #: PA.2683951

Date: 16/01/1920

Why did Prohibition come about?

BBC:

National mood – when America entered the war in 1917 the national mood also turned against drinking alcohol. The Anti-Saloon League argued that drinking alcohol was damaging American society.

Practical – a ban on alcohol would boost supplies of important grains such as barley.

Religious – the consumption of alcohol went against God’s will.

Moral – many agreed that it was wrong for some Americans to enjoy alcohol while the country’s young men were at war.In 1929, however, the Wickersham Commission reported that Prohibition was not working.

This September 1921 file photo shows contestants in the first Miss America pageant as they line up for the judges in Atlantic City, N.J. Second from left is Margaret Gorman, who won the competition.PA.9517261. Date: 01/09/1921

Ohio State University has more:

The prohibition movement’s strength grew, especially after the formation of the Anti-Saloon League in 1893. The League, and other organizations that supported prohibition such as the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union, soon began to succeed in enacting local prohibition laws. Eventually the prohibition campaign was a national effort.

During this time, the brewing industry was the most prosperous of the beverage alcohol industries. Because of the competitive nature of brewing, the brewers entered the retail business. Americans called retail businesses selling beer and whiskey by the glass saloons. To expand the sale of beer, brewers expanded the number of saloons. Saloons proliferated. It was not uncommon to find one saloon for every 150 or 200 Americans, including those who did not drink. Hard-pressed to earn profits, saloonkeepers sometimes introduced vices such as gambling and prostitution into their establishments in an attempt to earn profits. Many Americans considered saloons offensive, noxious institutions.

The prohibition leaders believed that once license to do business was removed from the liquor traffic, the churches and reform organizations would enjoy an opportunity to persuade Americans to give up drink. This opportunity would occur unchallenged by the drink businesses (“the liquor traffic”) in whose interests it was to urge more Americans to drink, and to drink more beverage alcohol. The blight of saloons would disappear from the landscape, and saloonkeepers no longer allowed to encourage people, including children, to drink beverage alcohol.

Some prohibition leaders looked forward to an educational campaign that would greatly expand once the drink businesses became illegal, and would eventually, in about thirty years, lead to a sober nation. Other prohibition leaders looked forward to vigorous enforcement of prohibition in order to eliminate supplies of beverage alcohol. After 1920, neither group of leaders was especially successful. The educators never received the support for the campaign that they dreamed about; and the law enforcers were never able to persuade government officials to mount a wholehearted enforcement campaign against illegal suppliers of beverage alcohol.

Former President Woodrow Wilson, with the help of an unidentified aide, leaves his Washington home in 1921. Mark Benbow, historian at the Woodrow Wilson House, has grown tired of hearing people wrongly say the 28th president was responsible for Prohibition because it occurred while he was in the White House.

Ref #: PA.2728206 Date: 28/11/1921

Ratified on January 29, 1919, the 18th Amendment went into effect a year later, by which time no fewer than 33 states had already enacted their own prohibition legislation. In October 1919, Congress passed the National Prohibition Act, which provided guidelines for the federal enforcement of Prohibition. Championed by Representative Andrew Volstead of Mississippi, the chairman of the House Judiciary Committee, the legislation was more commonly known as the Volstead Act.

Both federal and local government struggled to enforce Prohibition over the course of the 1920s. Enforcement was initially assigned to the Internal Revenue Service (IRS), and was later transferred to the Justice Department. In general, Prohibition was enforced much more strongly in areas where the population was sympathetic to the legislation–mainly rural areas and small towns–and much more loosely in urban areas. Despite very early signs of success, including a decline in arrests for drunkenness and a reported 30 percent drop in alcohol consumption, those who wanted to keep drinking found ever-more inventive ways to do it. The illegal manufacturing and sale of liquor (known as “bootlegging”) went on throughout the decade, along with the operation of “speakeasies” (stores or nightclubs selling alcohol), the smuggling of alcohol across state lines and the informal production of liquor (“moonshine” or “bathtub gin”) in private homes.

In addition, the Prohibition era encouraged the rise of criminal activity associated with bootlegging. The most notorious example was the Chicago gangster Al Capone, who earned a staggering $60 million annually from bootleg operations and speakeasies. Such illegal operations fueled a corresponding rise in gang violence, including the St. Valentine’s Day Massacre in Chicago in 1929, in which several men dressed as policemen (and believed to be have associated with Capone) shot and killed a group of men in an enemy gang.

Al Capone, called before a grand jury, talks to a man in Chicago, Ill.

March 21st, 1929. Capone was charged with tax evasion in 1931 and sentenced to 10 years in prison

Ref #: PA.2484235

Date: 21/03/1929

Authorities unload cases of whiskey crates labeled as green tomatoes from a refrigerator car in the Washington yards on May 15, 1929. The grower’s express cargo train was en route from Holandale, Fla., to Newark, N.J. (AP Photo) Ref #: PA.8642868 Date: 15/05/1929

Crime boomed:

Prohibition created an enormous public demand for illegal alcohol.

Gang leaders such as Al Capone and Bugs Moran battled for control of Chicago’s illegal drinking dens known as speakeasies.

Capone claimed that he was only a businessman, but between 1927 and 1930 more than 500 gangland murders took place.

The most infamous incident was the St Valentine’s Day massacre in 1929 when Capone’s men killed seven members of his rival Moran’s gang while Capone lay innocently on a beach in Florida.

Capone was imprisoned for income-tax evasion and died from syphilis in 1947.

It has been estimated that during Prohibition, $2,000 million worth of business was transferred from the brewing industry and bars to bootleggers and gangsters.

Rae Samuels holds the last bottle of beer that was distilled before prohibition went into effect in Chicago, Ill., Dec. 29, 1920. The bottle of Schlitz has been insured for $25,000.

Ref #: PA.2470949 Date: 29/12/1930

Large quantities of Canadian beer and whisky are being transported in cars from Amherstburg, Ont., Canada, across the frozen lower Detroit River, to the Michigan side of the international boundary line, Feb. 14, 1930. The cars are driven with one door open, so if the car goes through the ice the driver can scramble free. (AP Photo)

Ref #: PA.3325810

Date: 14/02/1930

Jack (Legs) Diamond on August 26, 1930, one of the biggest gang-leaders, racketeers, and bootleggers in America, who is reported to be en route for England in the liner ÂBalticÂ. It is stated that the captain of the ship has been asked to put Diamond into irons and take him back to New York. Diamond is the bitterest enemy Scarface Al Capone has in America. (AP Photo) Ref #: PA.9868985

An industry died. The National Library of Medicine:

In 1916, there were 1300 breweries producing full-strength beer in the United States; 10 years later there were none. Over the same period, the number of distilleries was cut by 85%, and most of the survivors produced little but industrial alcohol. Legal production of near beer used less than one tenth the amount of malt, one twelfth the rice and hops, and one thirtieth the corn used to make full-strength beer before National Prohibition. The 318 wineries of 1914 became the 27 of 1925.27 The number of liquor wholesalers was cut by 96% and the number of legal retailers by 90%. From 1919 to 1929, federal tax revenues from distilled spirits dropped from $365 million to less than $13 million, and revenue from fermented liquors from $117 million to virtually nothing.28

The Coors Brewing Company turned to making near beer, porcelain products, and malted milk. Miller and Anheuser-Busch took a similar route.29 Most breweries, wineries, and distilleries, however, closed their doors forever. Historically, the federal government has played a key role in creating new industries, such as chemicals and aerospace, but very rarely has it acted decisively to shut down an industry.30 The closing of so many large commercial operations left liquor production, if it were to continue, in the hands of small-scale domestic producers, a dramatic reversal of the normal course of industrialization.

Such industrial and economic devastation was unexpected before the introduction of the Volstead Act, which followed adoption of the Eighteenth Amendment. The amendment forbade the manufacture, transportation, sale, importation, and exportation of “intoxicating” beverages, but without defining the term. The Volstead Act defined “intoxicating” as containing 0.5% or more alcohol by volume, thereby prohibiting virtually all alcoholic drinks. The brewers, who had expected beer of moderate strength to remain legal, were stunned, but their efforts to overturn the definition were unavailing.31 The act also forbade possession of intoxicating beverages, but included a significant exemption for custody in one’s private dwelling for the sole use of the owner, his or her family, and guests. In addition to private consumption, sacramental wine and medicinal liquor were also permitted.

A prohibition-thirsty American Legionnaire goes into action in Windsor, Canada August 17, 1954, where the beer flowed freely, during the 1931 Legion convention across the river and the border in Detroit, Mich. His sign reads: ÂYou have liberty – we have a state – we want BeerÂ. Legion officials have decreed a Âsafe and sane convention this year, in Washington, D.C. (AP Photo)

Ref #: PA.9914531

Date: 01/01/1931

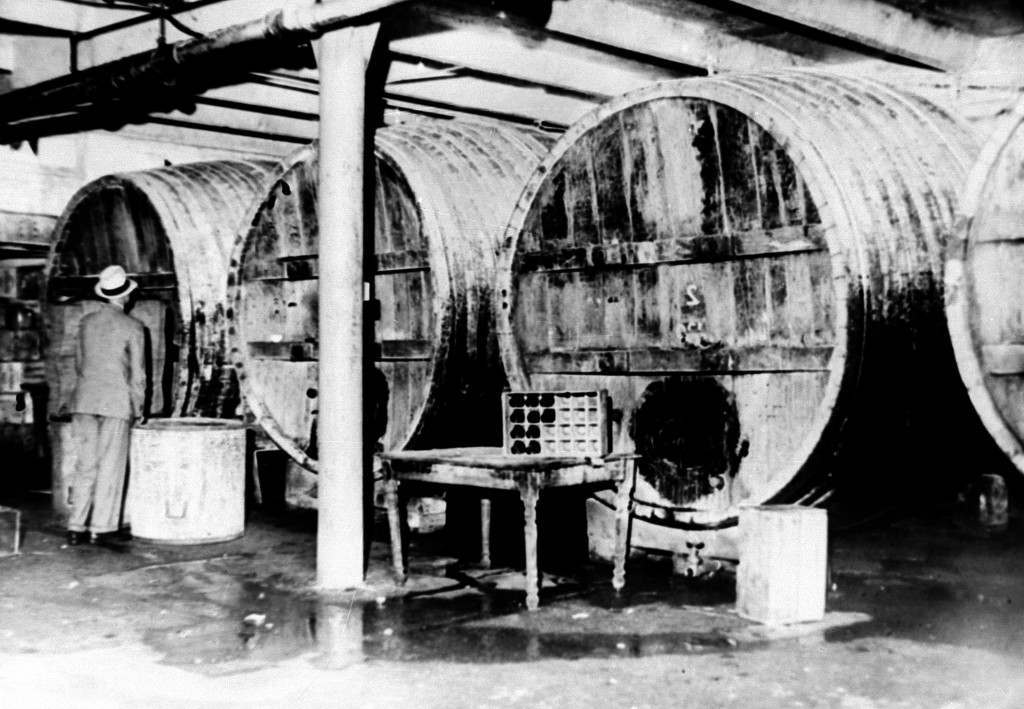

The largest distillery ever uncovered in Detroit was raided and prohibition officers are seen inspecting tanks and vats in one part of the plant, on Jan. 5, 1931. Each of these vats have a capacity of 15,000 gallons and there were thirteen on this floor alone. (AP Photo)

Ref #: PA.3325793

Date: 05/01/1931

Estelle Zemon shows the vest and pant-apron used to conceal bottles of alcohol to deceive border guards during the U.S. alcohol prohibition on March 18, 1931. (AP Photo)

Ref #: PA.3874951

Date: 18/03/1931

Estelle Zemon, left, and an unidentified woman model ways to conceal bottles of rum to get past customs officials during the U.S. alcohol prohibition, March 18, 1931. (AP Photo)

Ref #: PA.3874952

Date: 18/03/1931

Coast guardsmen stand in front of two truck loads of liquor that were seized after a midnight battle between three Falmouth policemen and a score of alcohol smugglers in the woods near Falmouth, Ma., April 14, 1931. One policeman was injured and all the rum runners escaped. (AP Photo)

Ref #: PA.8693290

Date: 14/04/1931

Large beer vats are seized by prohibition agents on West 25th Street in New York City, July 22, 1931. (AP Photo)

Ref #: PA.8664676

Date: 22/07/1931

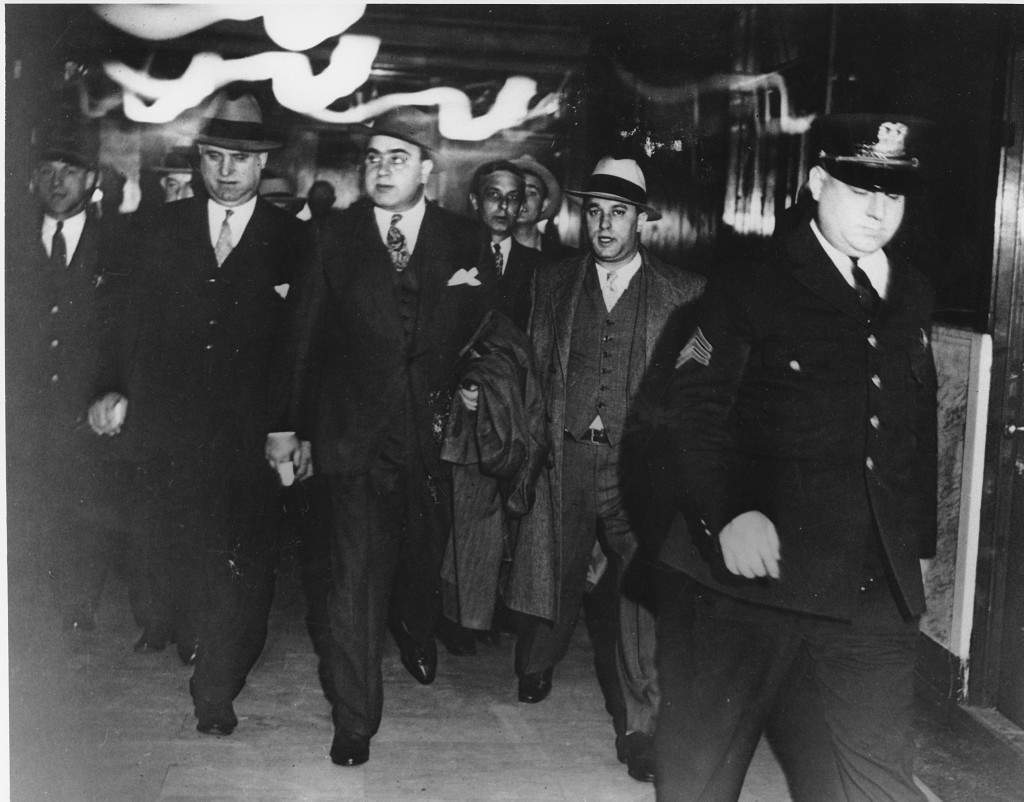

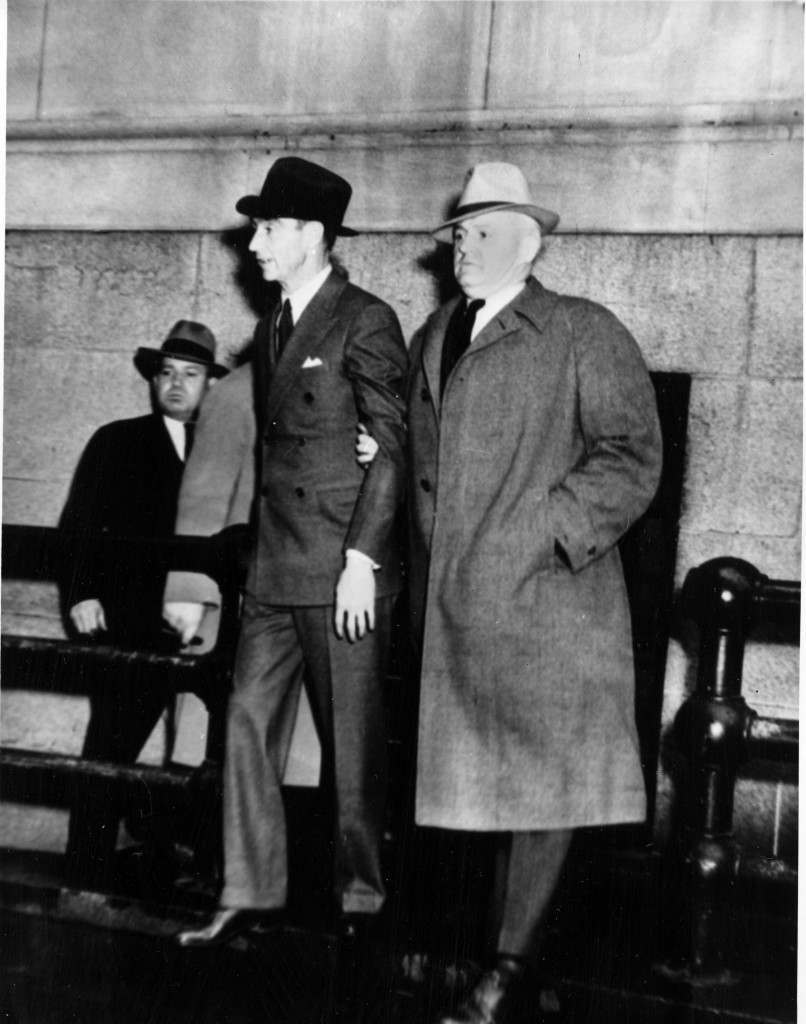

Jack “Legs” Diamond, center, and his attorneys, leaving the Federal Court in New York on August 8, 1931, after his conviction of owning an unlicensed still and conspiring to violate the prohibition law. The jury deliberated slightly more than two hours before returning its verdict. Under the terms of the law Diamond is subject to maximum sentence of four years in federal prison and a combined fine of $11,000. (AP Photo)

Ref #: PA.9966469

Date: 08/08/1931

Al Capone looks at the camera as he walks out of Federal Court in Chicago with his attorney Michael Ahern.

Oct. 11th, 1931. Capone is on trial for tax evasion

Ref #: PA.2534974

Date: 11/10/1931

Chicago crime boss Al Capone, center, in the custody of U.S. marshals, leaves the courtroom of Federal Judge James H. Wilkerson in Chicago.

Oct. 24th, 1931. He is facing tax evasion charges.

Ref #: PA.2534968

Date: 24/10/1931

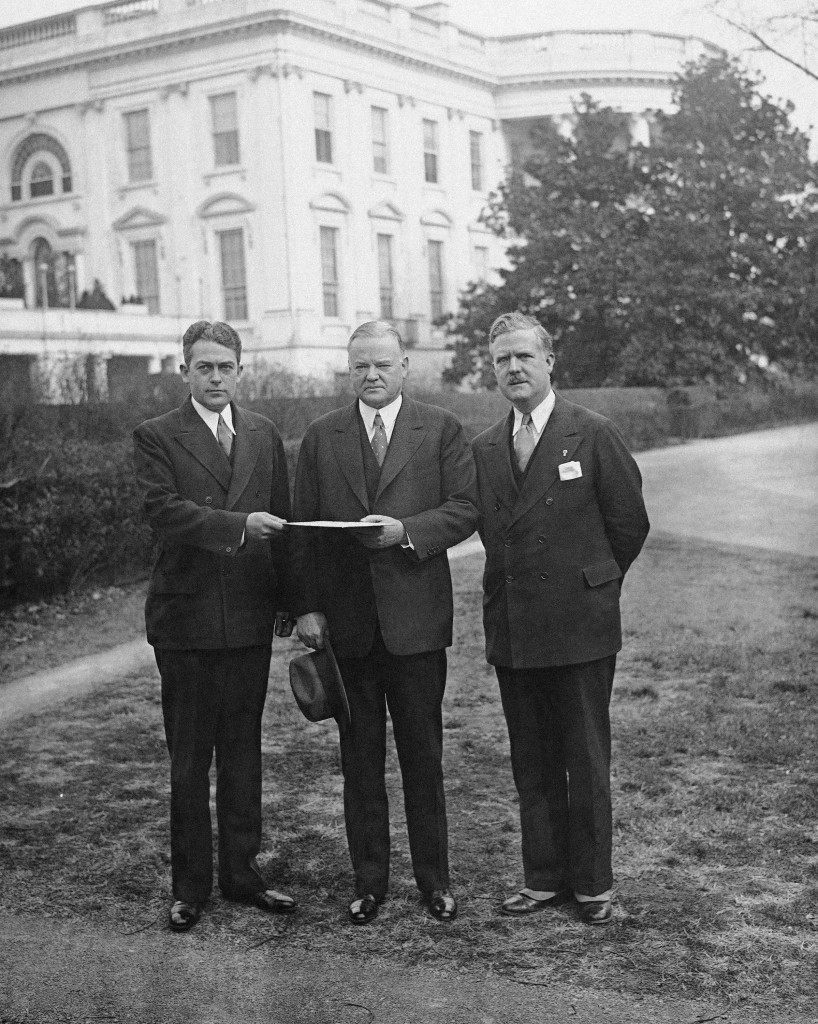

A program calling for a prohibition referendum and an additional expenditure of $25,000,000 for veterans relief was presented to President Herbert Hoover at the White House on Dec. 8, 1931, by Harry L. Stevens, Jr., commander of the American Legion. From left to right are Stevens, President Hoover and John Thomas Taylor, legislative representative of the Legion. (AP Photo)

Ref #: PA.9996645

Date: 08/12/1931

Prohibition agents uncover about $300,000 worth of liquor concealed in a pile of coal when they boarded the coal steamer Maurice Tracy in New York harbor on April 8, 1932. The inspectors shovelled coal for about an hour before they discovered the 3,000 bags of bottled beverages. (AP Photo)

Ref #: PA.2823668

Date: 08/04/1932

Coast guardsmen stand on a speed boat packed with nearly 700 cases of liquor they captured as it was unloaded at Newburyport, Mass., on the morning of May 6, 1932. They pursued the craft from outside the harbor into the Merrimack River. The crew fled as the government boat approached. (AP Photo)

Ref #: PA.8631861

Date: 06/05/1932

Delegates to the convention of the Women’s Organization for National Prohibition Reform gather in front of the Capitol Building for a group photo in Washington, D.C., April 13, 1932. The W.O.N.P.R. delegation is on hand to call on their representatives and senators to repeal the dry law. (AP Photo)

Ref #: PA.8655549

Date: 13/04/1932

Was prohibtion a healthy opiuon? Cato notes:

One of the few bright spots for which the prohibitionists can present some supporting evidence is the decline in “alcohol-related deaths” during Prohibition. On closer examination, however, that success is an illusion. Prohibition did not improve health and hygiene in America as anticipated.

Cirrhosis of the liver has been found to pose a significant health risk, particularly in women who consume more than four drinks per day. However, deaths due to cirrhois and alcoholism are a small portion of the total number of deaths each year, and alcohol can be considered only a contributing cause of most of those deaths.[25] Many people who do not drink develop cirrhosis, and the vast majority of heavy drinkers never develop it. Dr. Snell of the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, reported in 1931 that “we know now that cirrhosis occurs in only 4 per cent of alcoholic individuals.” Even in the worst pre-Prohibition year, recorded deaths due to alcoholism and cirrhosis of the liver amounted to less than 1.5 percent of total deaths.

An examination of death rates does reveal a dramatic drop in deaths due to alcoholism and cirrhosis, but the drop occurred during World War I, before enforcement of Prohibition. The death rate from alcoholism bottomed out just before the enforcement of Prohibition and then returned to pre-World War I levels.[29] That was probably the result of increased consumption during Prohibition and the consumption of more potent and poisonous alcoholic beverages. The death rate from alcoholism and cirrhosis also declined rather dramatically in Denmark, Ireland, and Great Britain during World War I, but rates in those countries continued to fall during the 1920s (in the absence of prohibition) when rates in the United States were either rising or stable.

Prohibitionists such as Irving Fisher lamented that the drunkards must be forgotten in order to concentrate the benefits of Prohibition on the young. Prevent the young from drinking and let the older alcoholic generations die out. However, if that had happened, we could expect the average age of people dying from alcoholism and cirrhosis to have increased. But the average age of people dying from alcoholism fell by six months between 1916 and 1923, a period of otherwise general improvement in the health of young people.

There appear to have been no health benefits from Prohibition. On the contrary, the harmlessness and even health benefits of consumption of a moderate amount of alco- hol have been long established. As early as 1927 Clarence Darrow and Victor Yarros could cite several studies showing that moderate drinking does not shorten life or seriously affect health and that in general it may be beneficial. According to the eminent Harvard psychologist Hugo Månster berg, “there exists no scientifically sound fact which demonstrates evil effects from a temperate use of alcohol by normal adult men.”

Workers of the Women’s Organization for National Prohibition Reform (WONPR) pose in a hansom cab in front of the New York City public library on May 20, 1932, during their personal campaign to repeal the Eighteenth Amendment. From left to right are, Mrs. Richard P. Haws, Mrs. Edward K. McCagg, Phyllis Thompson, Mrs. Linsley V. Dodge and Mrs. Moore Erwin. (AP Photo)

Ref #: PA.8649228

Date: 20/05/1932

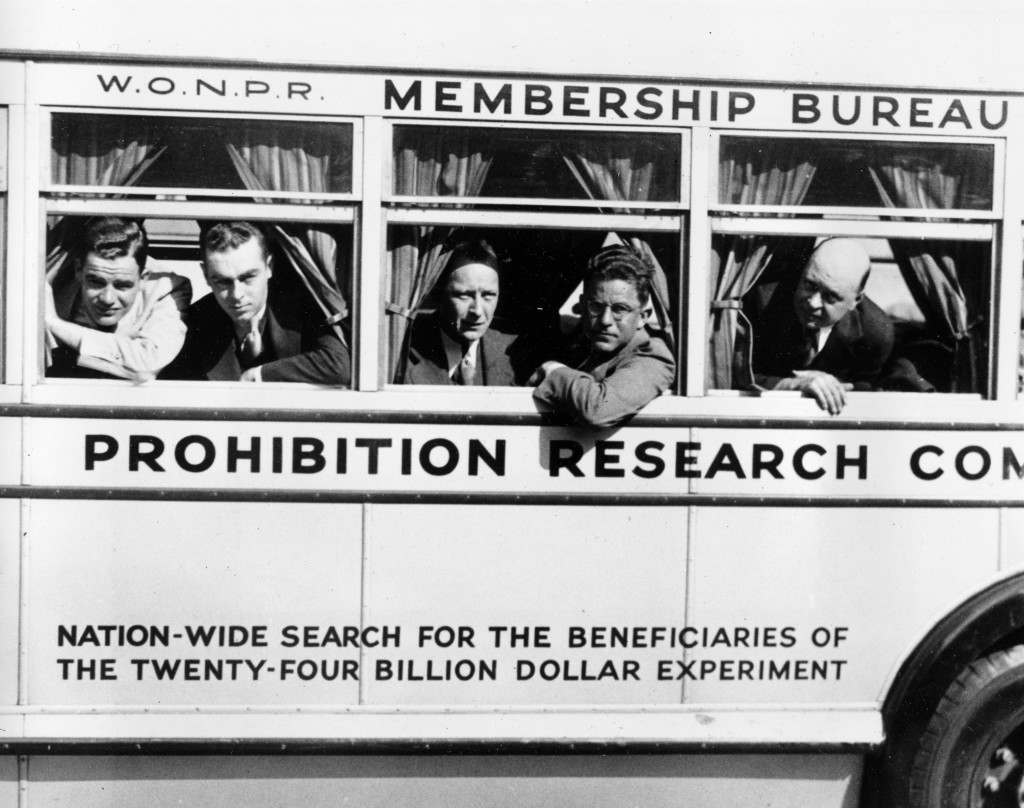

Five members of the alchohol Prohibition Research Committee depart on the bus Diogenes, named after the man who sought in vain for an honest man, in New York City, June 1, 1932. The membership is seeking one drunk who has been reformed by the 18th amendment in their campaign against the liquor ban. From left are, Stephen Duggan Jr., assistant investigator; Russell Salmon, chief investigator; Ernest Boorland Jr., member of the executive committee; Robert Nicholson, assistant director; and Paul Morris, director. (AP Photo)

Ref #: PA.8663757

Date: 01/06/1932

Drug Library looks at the repeal.

It is difficult to assess the relative numbers of the wet and dry partisans during the last few years of national prohibition. In terms of strength, however, the wets surely had the edge which less than two decades before had belonged to the drys. The new wet strength showed up at the National Convention of the Democratic party held in Chicago in 1932, where Mayor Cermak of that city filled the galleries with his supporters. And, though Franklin D. Roosevelt had wooed the dry vote for some time, he now came forward on a platform which favored the outright repeal of the 18th Amendment. Accepting his nomination, he stated:

I congratulate this convention for having had the courage, fearlessly to write into its declaration of principles what an overwhelming majority here assembled really thinks about the 18th Amendment. This convention wants repeal. Your candidate wants repeal. And I am confident that the United States of America wants repeal (Dobyns, 1940: 160).

While dry leaders looked on with disgust, Roosevelt was elected president and Congress turned a somersault. The repeal amendment was introduced February 14, 1933, by Sen. Blaine of Wisconsin and approved two days later by the Senate 63 to 23. The House followed four days later, voting 289 to 121 to send the amendment on to the States (Lee, 1963: 231). It required approval by 36 states. Michigan was the first state to ratify it; 39 states voted, on the amendment during 1933, with 37 approving its ratification and two-North and South Carolina-voting against its ratification. The final ratification was accomplished on November 7,1933, when Kentucky, Ohio, Pennsylvania and Utah gave their approval.

Congress officially adopted the 21st Amendment to the Constitution on December 5, 1933.

Women turn out in large numbers, some carrying placards reading “We want beer,” for the anti prohibition parade and demonstration in Newark, N.J., Oct. 28, 1932. More than 20,000 people took part in the mass demad for the repeal of the 18th Ammendment. (AP Photo)

Ref #: PA.6501630

Date: 28/10/1932

Mrs. William T. Healey, left, of Atlanta, Ga., and Mrs. Mae L. Hamilton, of Omaha, Neb., pose at the meeting of the National Executive Committee of the Women’s Organization for National Prohibition Reform (WONPR) at Princeton, N.J., on Dec. 6, 1932. They are wearing matching dresses with the small-lettered repeal as the motif for the design. (AP Photo)

Ref #: PA.8627073

Date: 06/12/1932

U.S. prohibition agents in Atlanta, Ga., intercept a carload shipment of liquor billed as vegetables from Fort Lauderdale, Fla., to Chicago, Ill., during the alcohol prohibition in this undated photo. Three sqauds of prison inmates, wearing striped prison gear and ankle chains, break up the bottles with sledgehammers. Inside the doors of the train cars, behind a few crates of string beans and potatoes, prohibition agents found crates of pint bottles of whiskey, several thousand in number, piled five deep in the freight car. A telegram from Fort Lauderdale tipped the federal men that the car was coming through Atlanta.

Ref #: PA.2470951

Date: 01/01/1933

Here is the ceremony employed by the Eagles club of Milwaukee to mark the passing of Âœ of one percent beer in favor of the 3.2 brew. At the stroke of the Eagles pictured at night on April 6, 1933, held up their drinking to give near beer a ÂDecent funeral. The sign over the coffin reads: Âhere lie the remains of Âœ of 1 percent. May he stay dead and never come to life again. (AP Photo)

Ref #: PA.7253520

Date: 06/04/1933

A crowd gathers on Broadway to celebrate the repeal of prohibition after midnight in New York City, April 7, 1933. A beer keg is held aloft at right.

Ref #: PA.2483836

Date: 07/04/1933

IT ent on

A delegation of women, joined by some men and children, pledge themselves to fight the prohibition laws as they stand in front of the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, D.C., April 14, 1933. Leading the delegation is Mrs. Henry W. Peabody, front row, left. The woman at center is Mrs. A. Haines Lippincott of Camden, N.J., and Mrs. Jesse Nicholson of Maryland is at right. (AP Photo)

Ref #: PA.8643825

Date: 14/04/1933

A crowd gathers as kegs of beer are unloaded in front of a restaurant on Broadway in New York City, the morning of April 7, 1933, when low-alcohol beer is legalized again. (AP Photo)

Ref #: PA.8660465

Date: 07/04/1933

People enjoy legal drinking as they gather at Cavanagh’s in New York City on Dec. 5, 1933 after the 21st Ammendment is ratified.

Ref #: PA.2483870

Date: 05/12/1933

Miss Bunny Swanson (left) impersonating the Spirit of Repeal, assisting happy art student Mourners in stowing away an effigy of prohibition during a ceremony at the Art Students League Building in New York on Dec. 4, 1933, a processional trip along Fifth Avenue, will follow, when the ÂRemains will be escorted to the ballroom of a New York Hotel, to lie in state during the league repeal ball and Revel on December 5. (AP Photo)

Ref #: PA.7253564

Date: 04/12/1933

Art students hustling an effigy of Prohibition into a coffin at the Art Students League building in New York on Dec. 4, 1933. A procession trip along Fifth Avenue will follow. (**Caption information received incomplete) (AP Photo)

Ref #: PA.9500737

Date: 04/12/1933

Mobster Dutch Schultz holds his head in agony as he lays in his hospital cot, his arm and chest wounds exposed, in Newark, N.J., on Oct. 23, 1935. Schultz and his bodyguards were shot by rival gangsters in a massacre and he died later the same night from his gun shot wounds. He was born Arthur Flegenheimer in Bronx, N.Y., in 1902. (AP Photo)

Ref #: PA.4097802

Date: 23/10/1935

Isadore “Kid Cann” Blumenfeld, center, charged with the murder of Walter Liggett, Minneapolis weekly newspaper publisher, has his manacles removed in court on the first day of his trial in Minneapolis, Jan. 20, 1936. At left is Thomas McMeekin of St. Paul, defense counsel. (AP Photo)

Ref #: PA.7428100

Date: 20/01/1936

A U.S. federal agent uses an axe to destroy the copper equipment used in this large illegal liquor plant during a raid near Griffin, Ga., on May 5, 1937. (AP Photo)

Ref #: PA.3388995

Date: 05/05/1937

U.S. Federal agents raid an illegal liquor plant near Griffin, Ga., where beer and wine are legal, on May 5, 1937. This plant in Lamar County is worth several thousand dollars. (AP Photo)

Ref #: PA.3388998

Date: 05/05/1937

Al Capone, right, Chicago’s infamous gang overlord during prohibition, leaves Harrisburg, Pa., on Nov. 16, 1939 with a federal officer for Lewisburg, Pa., where he was released after spending seven years in prison in Atlanta and San Francisco’s Alcatraz. (AP Photo)

Ref #: PA.8683302

Date: 16/11/1939

Owney Madden, left, owner of the Cotton Club during prohibition, is escorted by an unidentified detective as they leave police headquarters for questioning on May 4, 1940. (AP Photo)

Ref #: PA.8640050

Date: 04/05/1940

Marie Beiser, Baltimore beauty, took a personal hand in collecting scrap aluminum for defense purposes, July 25, 1941. Among the articles she added to a pile of castoffs gathered by her mother was an old aluminum beer keg of the pre-prohibition era. Marie was “Miss Maryland” in the 1940 Atlantic City beauty pageant. (AP Photo)

Ref #: PA.4716172

Date: 25/07/1941

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.