The Clash Revisited

Julien Temple’s latest raking of the coals of the punk ‘revolution’ looks at The Clash – a band often regarded with disdain and suspicion by the courtiers of the Sex Pistols (and indeed by the Pistols themselves).

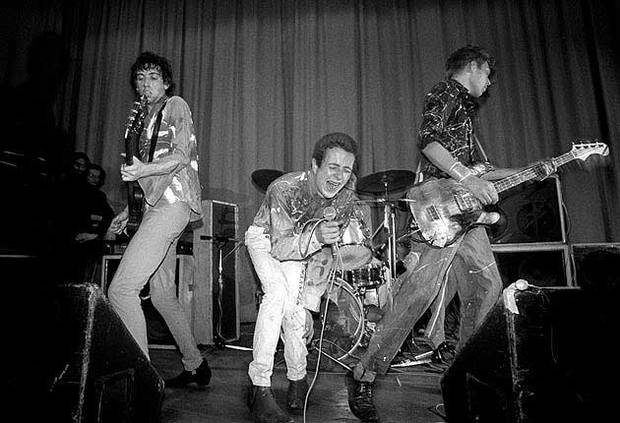

The film revolves around their performance on 1 January 1977 at the Roxy, a small run-down nightclub in Covent Garden which had been commandeered to serve as Punk HQ.

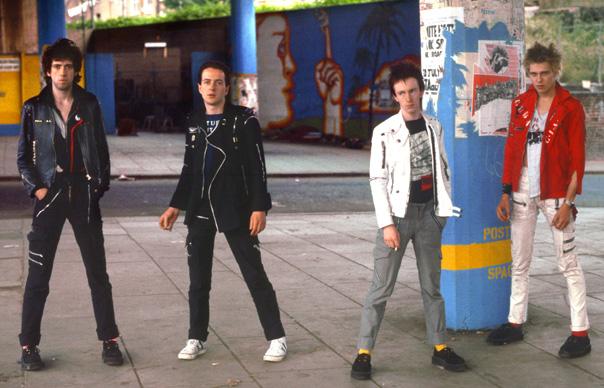

Although only a few months old, the band already had a distinct image: paint-splattered jumble sale clothes and stage backdrops of tower blocks painted by bassist Paul Simonon. They also had a unique body of songs, reflecting life on the dole or in dead-end jobs. A selection of these had been recorded as demos in November 1976…

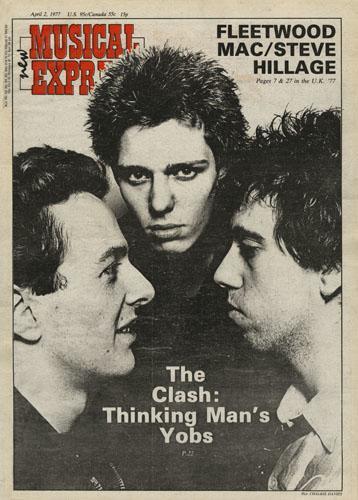

In January, the Clash signed for CBS (prompting cries of ‘Sell-out!’) and by the autumn, with the Sex Pistols having been effectively banned from performing, they were the best band on the planet. Joe Strummer was the nearest thing to a rock god that we were allowed to have. (Rock gods were anathema to the Year Zero. In the words of the Clash: ‘no Elvis, Beatles or The Rolling Stones in 1977’.)

The Clash were playing regularly now, and had developed from the shambolic ‘garage band’ of self-mythology into a dynamic and exhilarating live act.

On top of this, they were in the middle of a run of white-hot singles unequalled by any band since The Who back in the mid-sixties, which had started with the NME give-away ‘Capital Radio’ and would continue through ‘Complete Control’ and ‘Clash City Rockers’ to their punk-reggae triumph ‘White Man in Hammersmith Palais’.

It couldn’t last. By 1979, The Clash were a spent force. They were no longer ‘bored with the USA’ and were busy creating London Calling – a flabby double-album of second-rate Americana and preposterous protest songs about Spanish bombs, state repression, and, er, supermarkets. It ended up being named ‘album of the eighties’ by the old farts’ bible Rolling Stone, and that was exactly what it deserved.

As that awful decade dawned, they were just another rock band, stuck on the album-tour-album treadmill. They had played straight into the enemy’s hands. Far from killing the bloated beast of rock, punk had ended up giving it what the resolutely middle-of-the-road pop historian Paul Gambaccini described approvingly as ‘a much-needed shot in the arm’.

It would be easy to conclude that punk was a waste of time, and is best forgotten. In one sense, this is true. Musically, it produced a few great records, a fair number of decent ones, and – to these ears at least – a huge amount of crap. Today’s punks continue to thrash out their three chords with enthusiastic rage, but they are trapped in a blind alley, and the rest of the world has long since passed them by.

But The Clash’s best music still sounds great today. Listen and learn, kids, as Dave Lee Travis would say (though not, of course, with The Clash in mind). The Clash had it all: they looked great and they sounded great. In short, they were great. And they didn’t just talk the punk talk – they walked the walk, too. In those days, you really could turn up at a run-down hall and rub shoulders with Mick Jones and Joe Strummer. For a while, at least, they were a real ‘people’s band’, just like Jones’s heroes Mott The Hoople had been in the early Seventies.

Punk’s much-vaunted ‘political’ legacy is every bit as unimpressive, yet it is still revered in a way that the music is not. For that reason alone it is of more than just historical interest.

Punk’s nihilistic wing was, by definition, self-destructive, but the Sex Pistols at least had a glorious ‘fuck you’ attitude that you couldn’t help but admire. The problem came with the more worthy camp-followers, of whom the Clash were the unquestioned leaders. ‘Dole-queue rock’ was the phrase most commonly associated with the band, and it was a godsend for the music papers, which were desperate to get a handle on a phenomenon that had taken most of their dope-smoking ‘scribes’ by surprise.

This had unforeseen consequences. The Clash’s tower block chic and Joe Strummer’s ludicrously affected accent were the start of a middle-class cult of ‘street credibility’ which soon saw the noble Doctor Marten appropriated by right-on students, as they cut their hair and brought feminism, vegetarianism and other dubious causes to punk’s table. The deathly ‘post-punk’ era was born, with its humourless lyrics, boring tunes, horrible hennaed hair and boiler suits. Of the other, more overtly left-wing acolytes like Tom Robinson and Billy Bragg, the least said, the better.

Another consequence of the ‘politicising’ of punk was its reduction to a crude working-class caricature. This paved the way for Sham 69, a skinhead revival and Garry Bushell’s bizarre ‘Oi!’ movement, which claimed to be the true standard-bearers for The Clash’s proud tradition. (In the unlikely event that either Bushell or his protégés The Business have been invited back to my school to make speeches as distinguished old boys, and turned the air blue in true punk style, then I take it all back. All the best, Micky and Steve!)

Strummer’s own social conscience was the result of his personal experience. Like many of his champions in the music press, he was nostalgic for the radical mood of the sixties. As a veteran of the squatters’ movement, he instinctively sided with anyone who challenged authority, especially the police.

However, he had no involvement in real politics. So while the Clash played high-profile benefits for Rock Against Racism, they remained suspicious of organisations. And though their record sleeves, stage backdrops and self-made clothes were festooned with political slogans and symbols, they were always more interested in gestures than debate.

Strummer’s ideas may have been rough-and-ready, but they were heartfelt, and he wasn’t in the habit of mincing his words. In January 1978, The Clash appeared on a TV show called Something Else, described by the Radio Times as ‘an experimental magazine programme devised and produced by teenagers (with help from the Community Programme Unit) for teenage viewers’. The idea was for The Clash to play some songs and discuss issues relevant to young people with the left-wing Labour MP Joan Lestor.

The result probably wasn’t quite what the BBC had in mind. Having singularly failed to fire the audience’s enthusiasm with her defence of the Callaghan government, Lestor listened in horror as Strummer put forward his own suggestions, such as rounding up the rich and ‘putting them in camps’. Clever? Not really. Grown-up? Hardly. Funny? Not ’arf.

Of course, it is ultimately pointless to analyse the politics of The Clash, because their politics weren’t really the point. The point was passion. Everything Strummer did and said came from the gut. His rage was an emotional response to the world around him, and it is impossible to appreciate its impact without understanding the way we were before punk came along.

In the mid-seventies, Britain was a tense and volatile place, with soaring unemployment, rampant inflation, wage freezes, anti-police riots, IRA bombs, and a culture of random street violence. In the circumstances, one might have expected the mood of the times to be one of edginess and experimentation. Yet nothing could have been further from the truth.

Looking back, what strikes you most is the almost wilful refusal to acknowledge the real state of things. Television pumped out a diet of pap seemingly aimed at the asinine Home Counties families that populated its own sitcoms. The radio broadcast an endless round of bland pop and ‘golden oldies’. Rod Stewart –one of the few pop stars with real appeal – had split the Faces and degenerated into a preening old queen.

The fashion of the day was a weird 1930s mutation consisting of vast pinstriped Oxford bags, worn over hideous two-tone brogues with thick wedge soles. Huge shirt collars were splayed out over leather coats. Hair was blow-dried and sprayed rigid with lacquer. Enter a disco with its cut-price Deco decor and you risked asphyxiation by The Great Smell of Brut. There, under the revolving mirror-balls, we shuffled like zombies towards oblivion.

That is why punk was so important. Until then, conforming was everything. Not as in being a good boy and getting a pat on the head, but in the sense of fitting in with your peers. Irony and individuality weren’t big back then, and anything that marked you out as a ‘weirdo’ or a ‘poof’ could get you into trouble. Being a punk was asking for it, but it was worth the added tension and the occasional kicking. As Joe Strummer sang: ‘What we wear is dangerous gear / It’ll get you picked on anywhere / Though we get beat up, we don’t care / At least it livens up the air’.

That was the thing about punk – it made you feel alive. And it put the shitheads on the back foot. Suddenly the local kingpins weren’t so important. A few teenage years of boozers and discos followed by marriage and a job suddenly didn’t seem such a good deal. Now there was a wider world to explore, with gigs and parties all over London and a new crowd of people who didn’t give a monkey’s what others thought of them.

Overnight, the world seemed completely different. Through our eyes, everyone else appeared comically – and sometimes scarily – grotesque. Teds who lived in the past with their Gene Vincent records. Beermat-flippers down the pub. Girls who got engaged at 16 and said ‘Don’t be stew-pid!’ whenever anyone said anything remotely unusual. Teachers with beards and brown suits. Middle-aged swingers. Old Bill (who picked on you for nuffink!). Hardworking homeowners who ‘weren’t prejudiced’ but ‘wouldn’t want them living next door’. Moderates who ‘weren’t prudes’ but thought that some of the blue material around these days ‘went too far’. Brain-dead comedians who made jokes about punks living in dustbins. Geezers with flat noses and tinted bins who thought it was ‘time to give the NF a go’. Skinny little tossers who sat drunk on the last train home and puked over their ties. Smug students with loud voices and big badges. Ordinary, decent people who ‘didn’t like to make a fuss’. And any other cunts I may have overlooked.

Punk wasn’t all about hate, but it was partly about it. It made you hate your second-rate, sordid surroundings. It made you hate anything and anyone that restricted your freedom. Above all, it made you hate the life that lay in wait for you, and the person you might become. It was a wake-up call to a sleeping generation.

From time to time I bump into former punks. They are a varied bunch – not quite anything from a duke to a dustman, but not far off. And whatever they are doing now, you can always spot them. However grown-up, or responsible, or rich, or influential they are, they all have something in common: a little punk inside their head who refuses to give respect to people who don’t deserve it, or take seriously the moralistic platitudes which we are served up as a design for living. This is nothing to shout about in itself, but if you have that inner punk, you have a choice. You can ignore him or follow him – it’s your call.

Nowadays, every kid grows up expecting the best for himself. People complain that the young have no respect for others, yet demand respect for themselves. People say a lot of things, and to quote Joe again, ‘You know what they said? Well some of it was true’. But if I had to choose between today’s kids, with their giant egos and grandiose expectations, and my generation, for whom a trip ‘into town’ (from Eltham to the West End) was a big deal, and a bunk-up and a fight was about as good as life got, then there’s simply no contest.

The Clash didn’t change the world, but they changed my world. In a way, they saved my life. For that, I’d forgive them anything.*

*With the possible exception of ‘Rock the Casbah’.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.