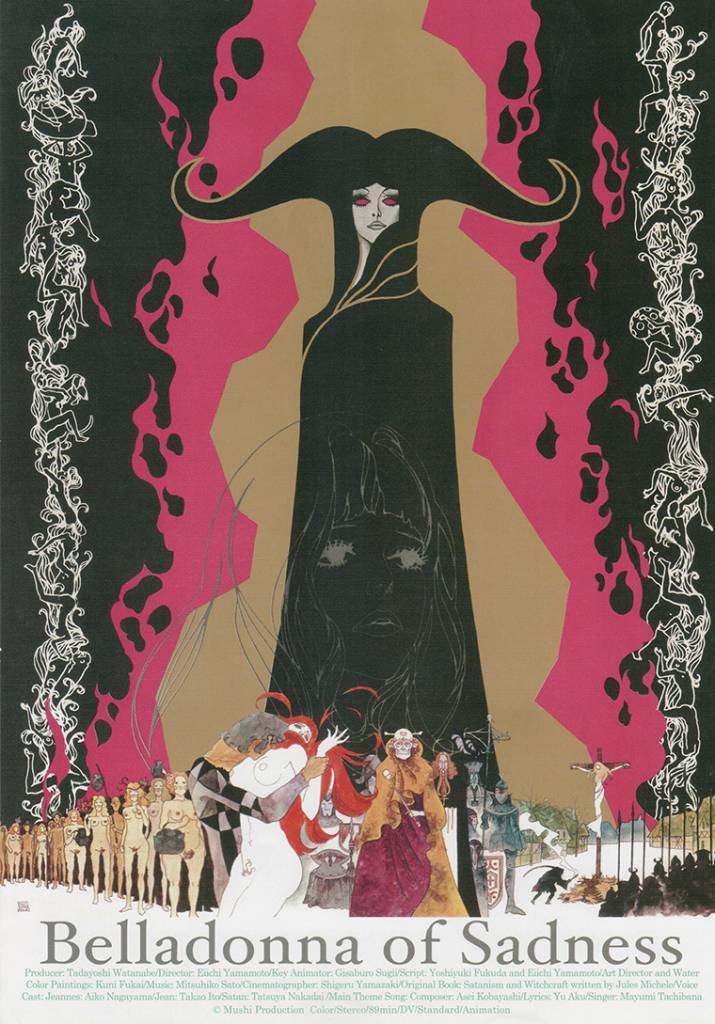

Belladonna of Sadness (Kanashimi no Belladonna) is a 1973 “long-forgotten X-rated psychedelic animation gem about one woman’s violation, persecution, and sexual awakening produced over four decades ago by the makers of Astro Boy.”

The trailer is trippy, shifting and captivating:

Cinelicious reviews:

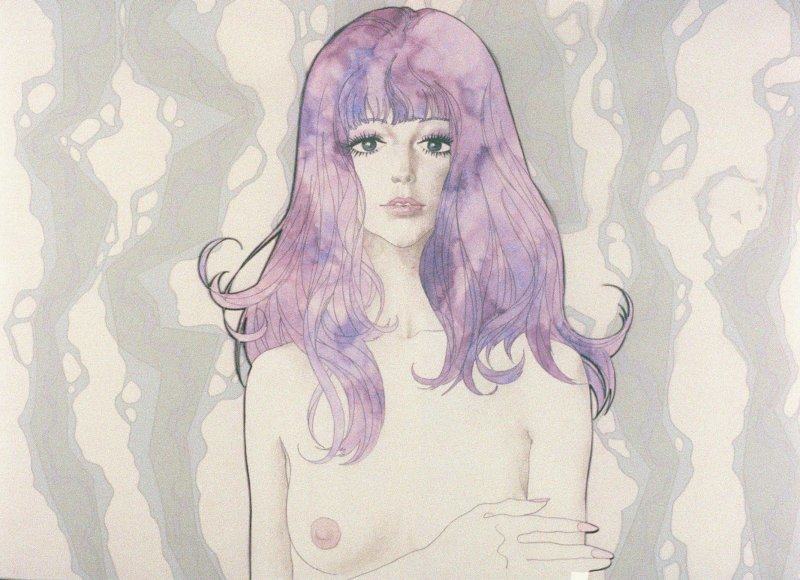

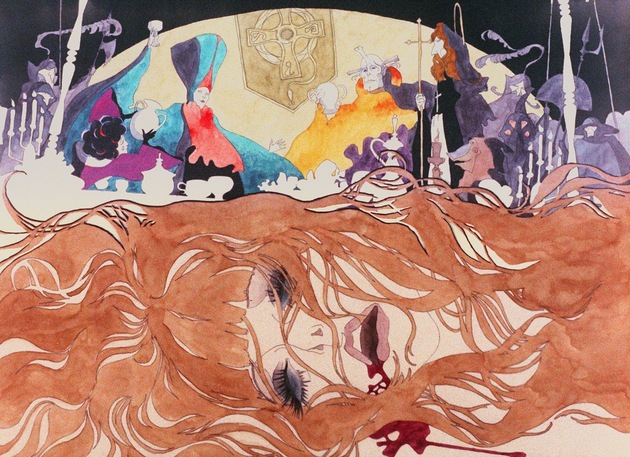

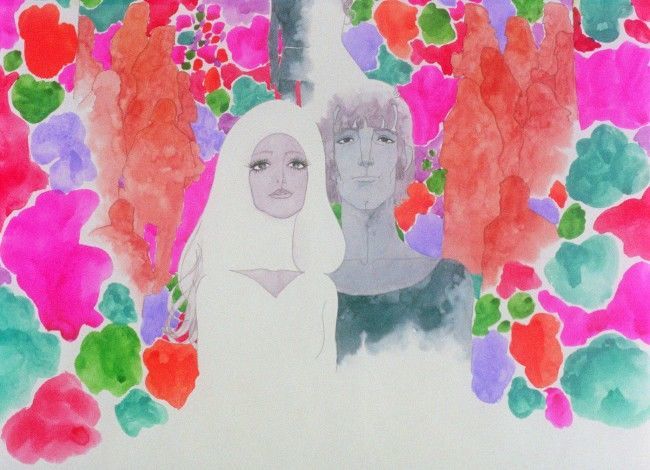

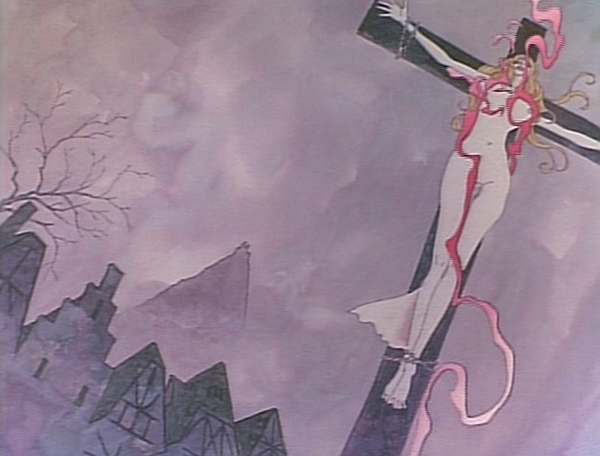

…a mad, swirling, psychedelic light-show of medieval tarot-card imagery with horned demons, haunted forests and La Belle Dame Sans Merci, equal parts J.R.R. Tolkien and gorgeous, explicit Gustav Klimt-influenced eroticism. The last film… unfolds as a series of spectacular still watercolor paintings that bleed and twist together. An innocent young woman, Jeanne (voiced by Aiko Nagayama) is violently raped by the local lord on her wedding night. To take revenge, she makes a pact with the Devil himself (voiced by Tatsuya Nakadai, from Akira Kurosawa’s RAN) who appears as an erotic sprite and transforms her into a black-robed vision of madness and desire.

Extremely transgressive and not for the easily offended, Belladonna is fueled by a mindblowing Japanese psych rock soundtrack by noted avant-garde jazz composer Masahiko Satoh.

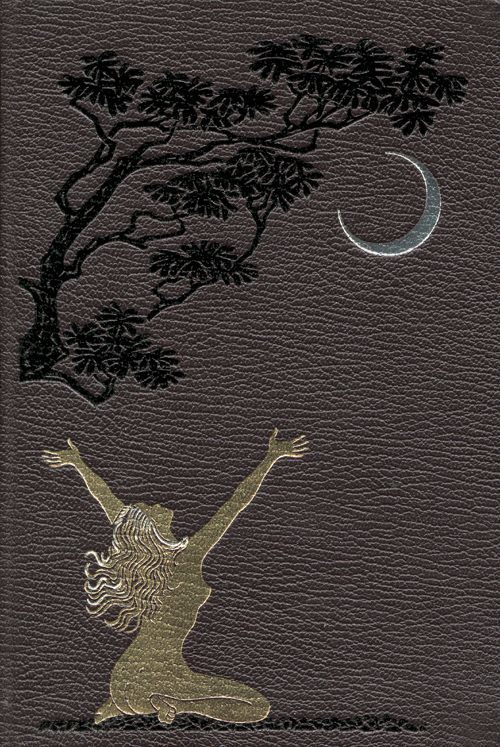

The film is based on French writer Jules Michelet’s 1862 treatise Satanism and Witchcraft.

Belladonna is an adaptation of La Sorcière, the 1862 novelized history of satanism and witchcraft in the late middle ages. The book was written by feminist, freethinker, and Frenchman Jules Michelet [1798-1874], who, like many other post-revolution French intellectuals, was eager to condemn the barbaric European forces of the prior few centuries. In Michelet’s story, the practice of witchcraft is not simply the leftover trace of ancient pagan traditions, but an active rebellion against an oppressive church and system of government. While the church expected serfs to suffer and slave away during their time on earth with only the promise of a better afterlife to console them, witchcraft provided a glimpse of happiness in the here and now.

Jules Michelet, French historian, c1860-1874. Michelet (1798-1874) is best known for his 17-volume History of France (1833-1867).

Where the church feared the imperfections of nature, witchcraft embraced them. Where the church could only respond to ailments with prayer and holy water, witchcraft offered painkillers and psychoactive potions from datura plants. According to Michelet, the spirit of rebellion and experimentation found in 14th century witchcraft was a progenitor of the enlightenment values yet to come. Furthermore, this was a movement led by women, those who likely suffered the most at the hands of the church and the feudal system. He insinuates that society’s emancipation from oppression is contingent on female liberation and sexual empowerment. It’s easy to imagine how these ideas must have resonated with the revolutionary leftist Japanese filmmakers of more than a century later (yes, they were working in animation too).

The film adaptation of La Sorcière is often very faithful to the book, to the point of replicating much of its dialogue. It tells the story of an archetypal witch who suffers a series of misfortunes that lead her down the path from being a chaste, obedient peasant’s wife, to giving in to her awakened earthly desires, to finally blossoming into the bride of Satan himself. The process of selling one’s soul to the Devil can be interpreted literally or metaphorically, but keep in mind that at least according to Michelet, those who would enter into such a pact in the middle ages presumably believed they were literally sacrificing eternity for just a glimmer of relief from a cruel and bleak life. A pact with Satan was the ultimate act of desperation, not just a casual mistake. On the other hand, none of the “powers” that Jeanne acquires from the Devil require any sort of supernatural explanation. They are simply things that Medieval society has withheld from her: an independent spirit, a liberated sexual libido, communion with nature, an inquisitiveness that allows her to discover the medicinal properties of plants, an air of confidence that enhances her powers of persuasion. Her relationship with the Devil may be nothing but a psychological coping mechanism for the brutality she suffers.

The film was designed by illustrator Kuni Fukai, whose drawings may appear to be more Western than Japanese. But his style seems to be a sort of late 60’s psychedelic Art Nouveau revivalism inspired by the likes of Aubrey Beardsley’s Victorian parodies, which were likewise inspired by erotic-grotesque shunga prints, thus coming full circle back to Japan. Much of the film features Fukai’s drawings directly, with the camera panning over still frames, but the film often transitions seamlessly into full animation thanks to animation director Gisaburo Sugii. This extra motion tends to happen during the film’s numerous sex scenes, but they are generally not visually explicit. Instead, they are animated in a variety of highly stylized expressionistic ways, taking full advantage of animation’s ability to caricature form and motion.

The third entry in the Animerama trilogy of racy adult animated features was produced in the late ’70s by the company founded by Osamu Tezuka, the grandfather of anime. But the series bombed, and Tezuka’s studio Mushi Productions went under shortly thereafter. Belladonna of Sadness never even made it across the Pacific.

Ever since then, Belladonna’s lived on only in the rarefied hearts, minds, and collections of obscure art fiends and animation hounds. Prized for its dreamlike watercolors and funkadelic score, Belladonna earned cult status for its striking visuals, brutal violence, and explicit sexuality, folded into a boldly controversial feminist narrative.

Belladonna of Sadness has recently received a 4K restoration by Los Angeles-based post-production company Cinelicious. Belladona of Sadness is TCJ spoke to the artists:

Dennis Bartok: “The restoration and re-release of Belladonna of Sadness actually came out of an informal lunch in Spring of 2014 here at the Cinelicious offices with Hadrian Belove, founder and head of The Cinefamily non-profit film organization in Los Angeles. I asked Hadrian, “If you could restore any rare or unknown films which would you pick?” — and the first one he mentioned was Belladonna of Sadness…

“Although I’m a huge fan of Japanese cinema including anime, and had shown literally hundreds of rare and classic films… I’d never seen or even heard of Belladonna — which is some indication of just how far off the radar it is! I watched a pretty fuzzy, dupey version illegally posted on YouTube and was immediately blown away by the mixture of eroticism, psychedelia, and the occult, along with the phenomenal fuzz-stoked soundtrack by Masahiko Satoh. Since the film had never been released on the U.S., I started a detective search to track down the rights holder in Japan: through a colleague in Germany, Andreas Rothbauer, I was put in touch with Stephan Holl at Rapid Eyes Movies there who’d released Belladonna on DVD in Germany and France — Stephan kindly gave me contact info for Kiyo Joo at Gold View Company in Japan, who represents Mushi Productions, the original production company for the film.

And now for the new brighter trailer.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.