Photography and modern warfare grew up, side by side, on battlefields, burial grounds, and in the trenches and ruined European cities of World War I. In France, German photographer Hans Hildenbrand took what are some of the few color photographs of the front lines. “The overwhelming majority of photos taken during World War I were black and white, lending the conflict a stark aesthetic which dominates our visual memory of the war,” Der Spiegel explains.

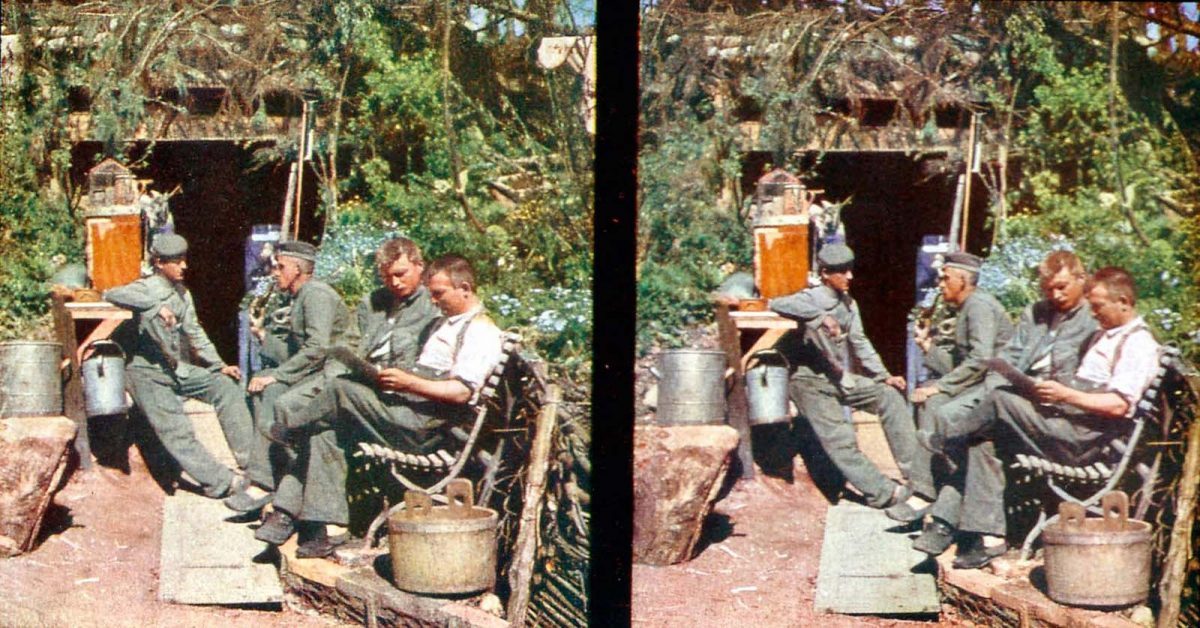

If Hildenbrand’s photographs look staged, it’s because they were, “not for reasons of propaganda, but rather because the film he was working with wasn’t sensitive enough to capture movement.” The limitations of color at the time parallel those of the medium itself in 1847, when the first photographer took images of war, fragile daguerreotypes from the Mexican-American war that showed staged portraits, landscapes, and burial grounds.

While the anonymous 1847 photographer’s images “provide insight into daily life on the periphery of the war, they are especially notable for what they do not depict,” Megan O’Hearn writes at Artstor. “In them, we see neither active battles or wounded and dead bodies, nor the idealization and glory sometimes associated with war.” This is mostly because the technology “rendered moving subjects as mere blurs,” just like Hildebrand’s color process.

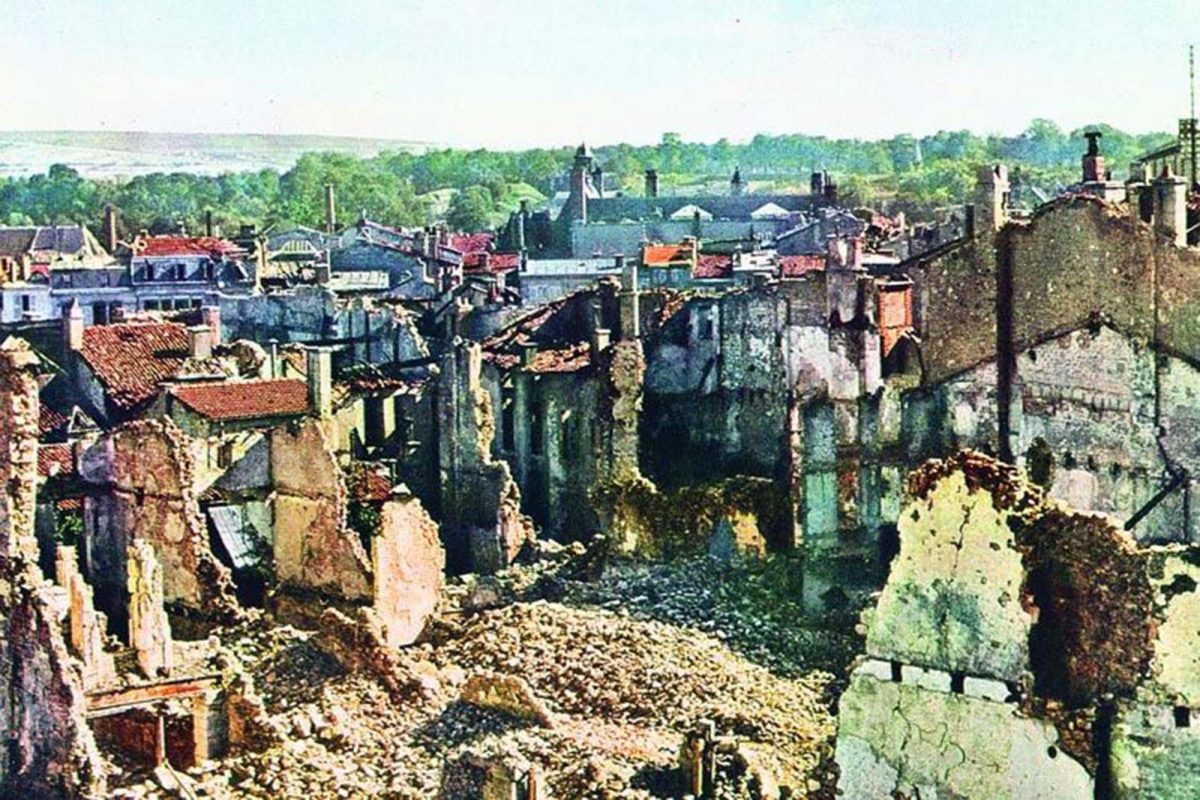

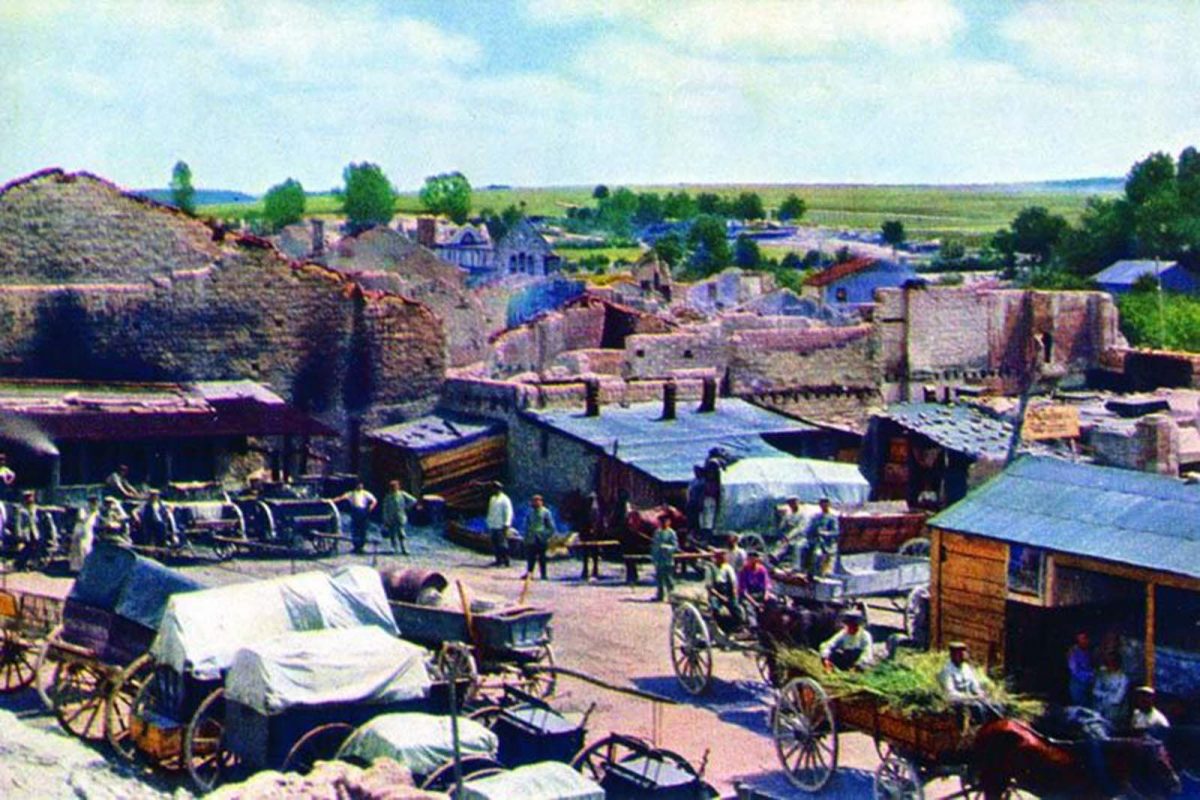

Hildenbrand’s photographs telegraph a placid absence of real conflict, and also no obvious attempts to glorify its soldier subjects, who often appear standing leisurely in the distance, dwarfed by ruined landscapes like figures in a painting. The “autochrome” techniques Hildenbrand used, as well as his eye for composition, contributes significantly to this effect.

Long after it became a commercial pursuit available to the masses (some of whom immediately set about hoaxing others), photography was assumed by most educated people to represent objective reality. That belief was so persistent that even a skeptic like Virginia Woolf could write in 1938 that “photographs, of course, are not arguments addressed to the reason; they are simply statements of fact addressed to the eye.”

Governments quickly realized that photographs do not have to be doctored or faked to make an “argument addressed to reason.” They simply needed to be posed carefully and selected just so. In 1853, when the Crimean War began, “the British government,” O’Hearn writes, “sought to document the war as a means of uniting the public behind their increasingly unpopular war efforts.” They dispatched four official photographers to tell a story people would respond to, though many of the results did not survive to publication.

By the time of World War I, photography on the battlefield had become commonplace by comparison. Hildenbrand was one of 19 photographers sent by the Kaiser to document the war. “’Embedded’ with a platoon of German troops in Champagne from June 1915 to January 1916,” Der Spiegel notes, his photographs would have been subject to censorship. Some of them, like the photo of a military camp above, were published as postcards.

One of the most striking things about Hildenbrand’s oevre is how freely he records scenes of destruction. During World War II, both sides became much pickier about what kinds of scenes they would let photographers document. During World War I, images of destroyed churches were a persistent motif.

However, both Hildenbrand and French contemporary Jule Gervais-Coutellemont (see his 1916 view of Verdun, above) used color photography during the war to bring even to destruction an irresistible kind of beauty, with ruins rendered like Impressionist works of art. It’s no wonder Hildebrand went on to photograph stunning landscapes and staged portraits of villagers for National Geographic. His war photos draw the eye away from guns, trenches, and bivouacs to the blasted cities and verdant forests and mountains beyond.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.