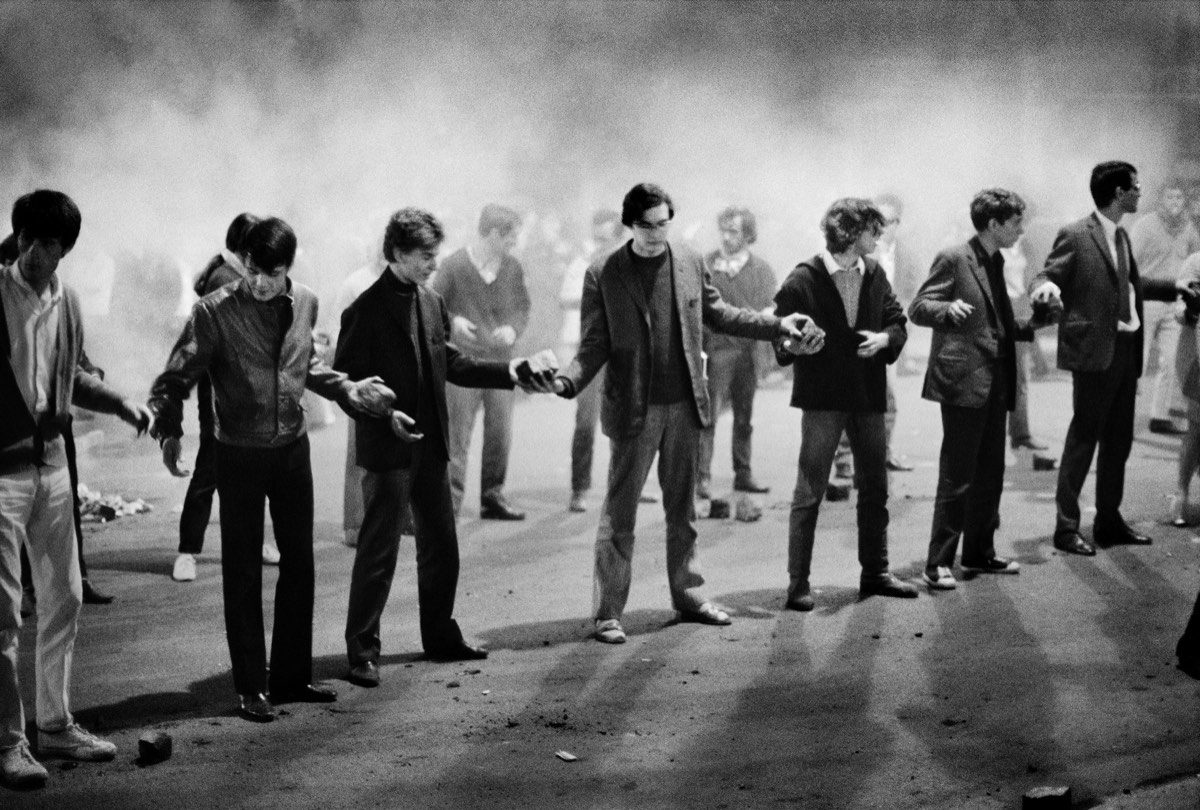

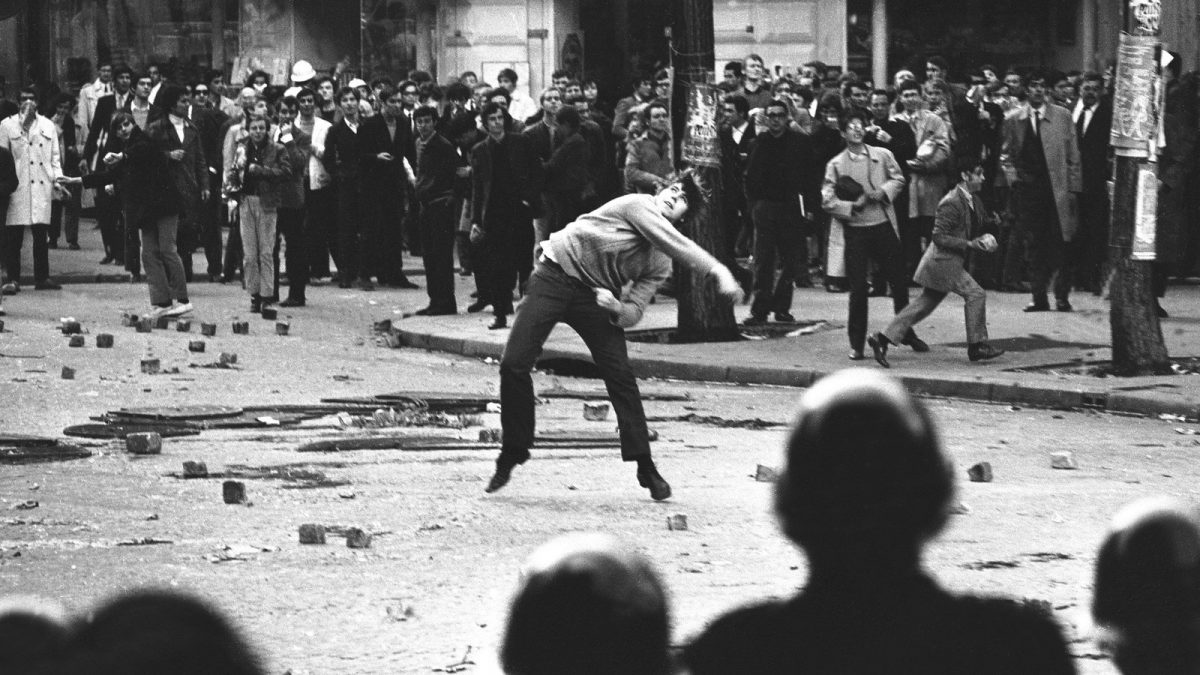

“I’ve never seen such violence in a western capital as I saw in Paris that month,” photographer Bruno Barbey said of documenting the Paris uprisings in May of 1968. Barbey was no newcomer to such scenes. The Moroccan-born French photographer had traveled the world, first coming to prominence for his three-year project The Italians, which attempted to capture “the spirit of a nation,” writes The Independent Photographer, and he had undertaken another major series to “document cultural similarities and differences between European and African countries.”

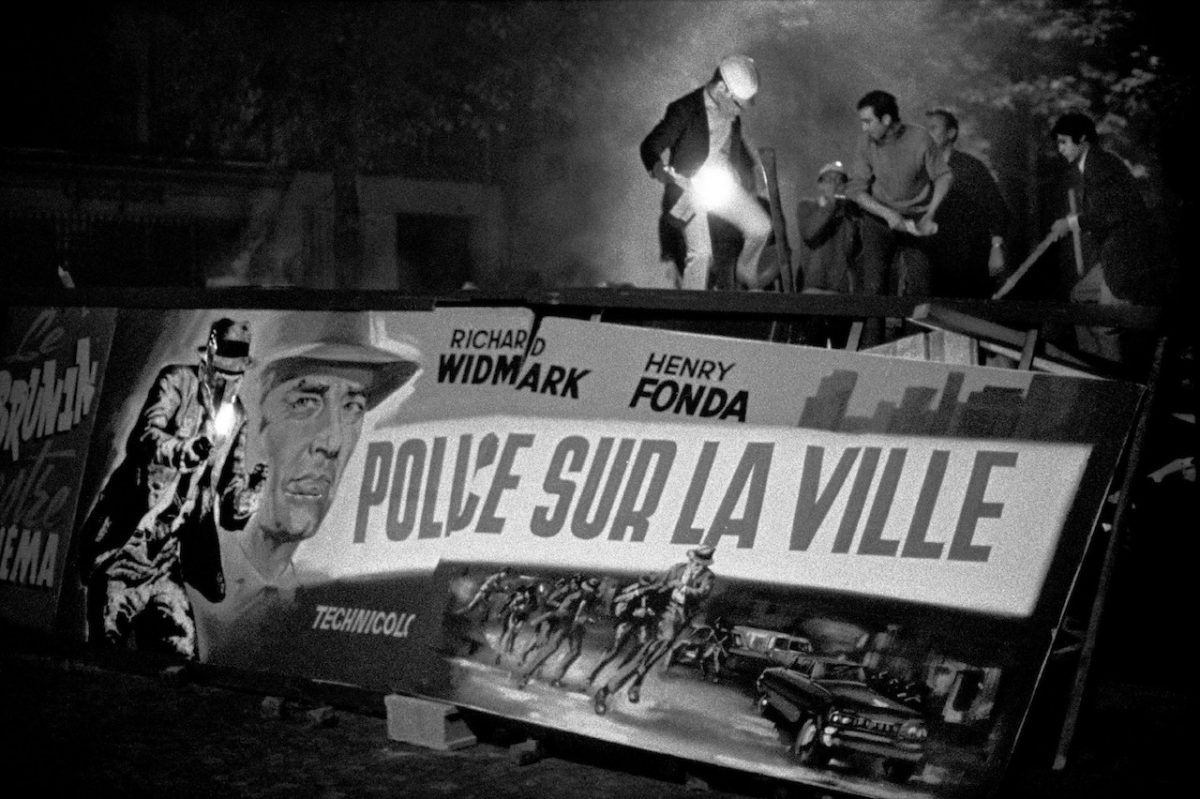

Barbey had also made the shift to color in 1966 while working in Brazil, which he maintained was “one of the high points of his career.” But when he arrived in Paris two years later on commission, he chose to return to black and white, as he would do in later photographs of starving refugees in India and a camp of armed Palestinian Al Fatah fighters. Perhaps there was something about the stark morality of these scenes – in the photographer’s own conviction, that is – which drew him back to higher contrast.

Rather than as a neutral observer, Barbey entered the fray, along with photographers Marc Riboud and Henri Cartier-Bresson with a belief in the justness of its cause. As Miss Rosen writes at Blind:

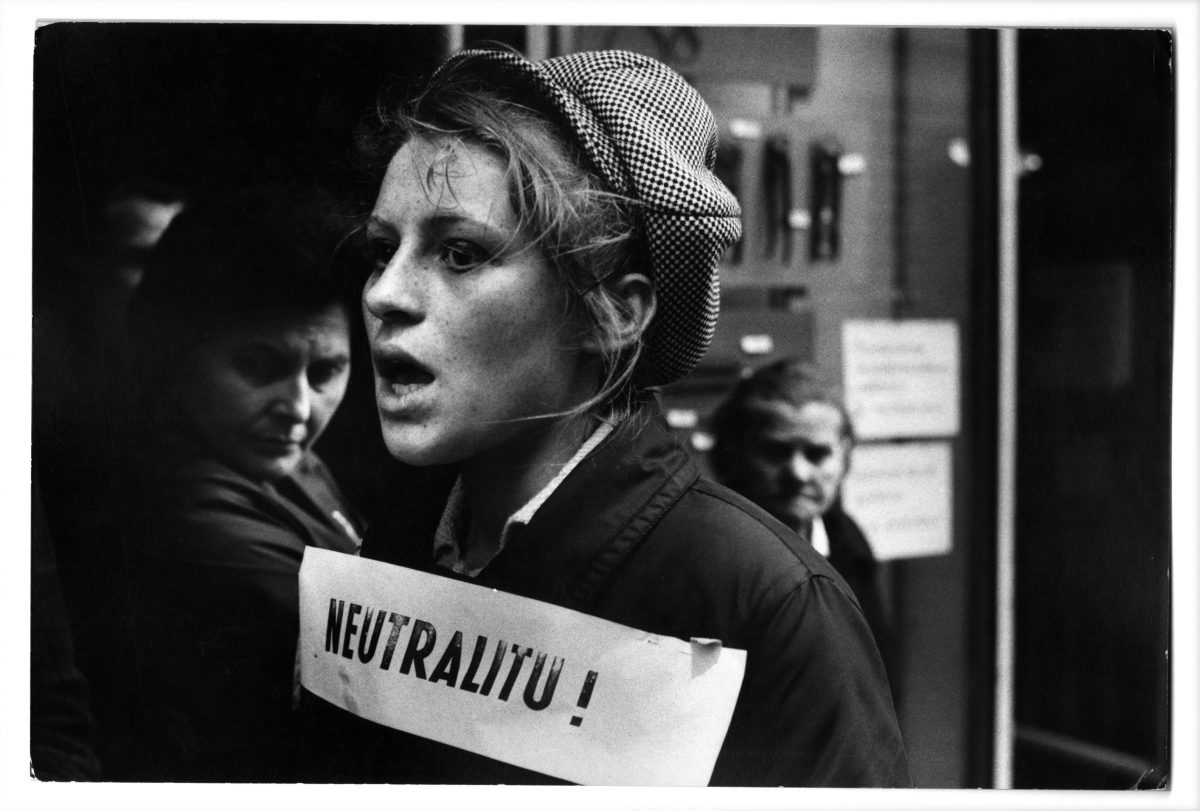

Although Barbey wasn’t a militant, he acknowledged his sympathies lay with the demonstrators, and spoke in awe of what he witnessed during that time. “Many were disillusioned at the end of the May movement but I wasn’t; I was occupied with other causes that were more urgent.” Barbey revealed.

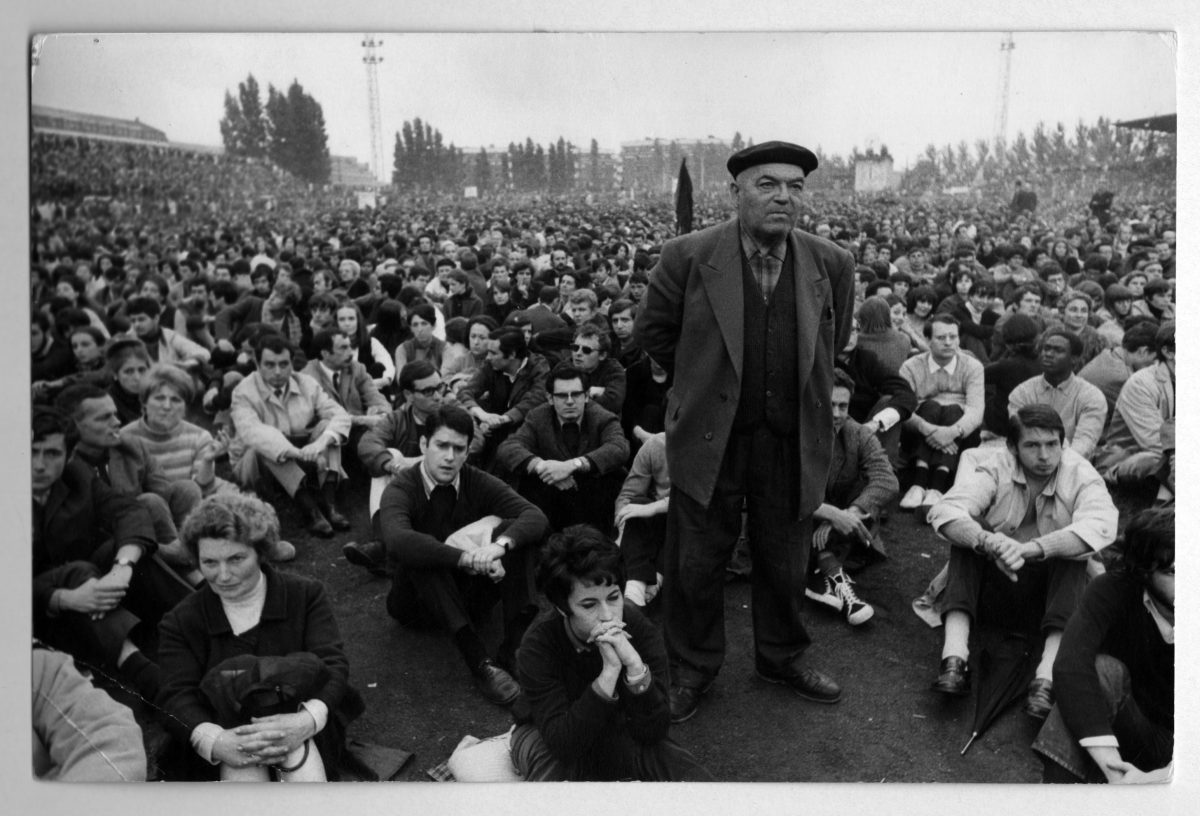

The Paris uprising of 1968 is typically characterized as a movement of Marxist and anarchist students and their disgruntled professors, an idea that reduces its scope to the generation of disaffected, middle-class “future bosses” and ignores the significant participation of workers all over the country. Barbey’s photographs seem to reinforce this impression. Some resemble stills from an unmade Jean-Luc Godard film, with their young, hip, lefty subjects.

But the struggle was bigger than the students in Paris, whose demands were uncompromisingly, stridently utopian. It was, writes Michell Abidor, who compiled an oral history after the events, a fight for “a new way of arranging society, for new forms of economic and social and class relations” and included workers in factories around the country, “united against a sclerotic Gaullist state” and its conservative hierarchies.

Nonetheless, there was a split between workers and students. The desires of Parisian demonstrators “found their purest expression in their slogans, graffiti and posters,” that read “The hindrances placed on pleasures incite unhindered pleasures”; “Life, quickly!”; and, of course, “Be realistic—demand the impossible.” By contrast, workers like Bernard Vauselle remembered that “it was really the bread-and-butter demands we were interested in, not the political demands.” For most of those on the barricades, the two were inseparable.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.