“I think people will continue to enjoy the Coyote cartoons we made because he makes the same kind of errors we do. We tried to inject character in them, but we didn’t do it consciously”

– Chuck Jones

Chuck Jones (September 21, 1912 – February 22, 2002) was the hymned American animator of, among other cartoon characters, Warner Brother’s Bugs Bunny, Daffy Duck, Porky Pig, Pepé Le Pew, Road Runner and Wile E. Coyote.

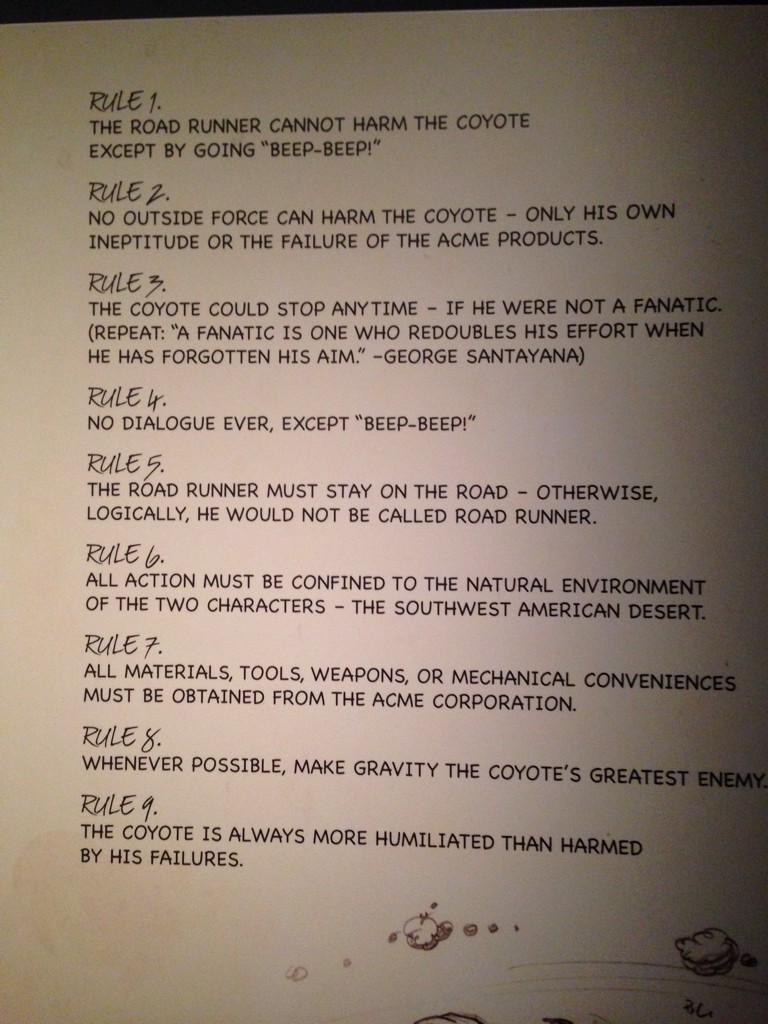

His list of rules for the Road Runner and Wile E. Coyote cartoons show us how he plotted a story.

Ever since the pair debuted on 17 September 1949 in a Looney Tunes short titled “Fast and Furry-ous”, he kept it simple. Film director Amos Posner shared this photo taken at the What’s Up, Doc? The Animation Art of Chuck Jones exhibit at New York’s Museum of the Moving Image:

We know the importance of making lists. And this one first appeared in his 1999 autobiography Chuck Amuck: The Life and Times of an Animated Cartoonist. Although back then there were 11 rules.

1. The Road Runner cannot harm the Coyote except by going “meep, meep.”

2. No outside force can harm the Coyote — only his own ineptitude or the failure of Acme products. Trains and trucks were the exception from time to time.

3. The Coyote could stop anytime — if he were not a fanatic.

4. No dialogue ever, except “meep, meep” and yowling in pain.

5. The Road Runner must stay on the road — for no other reason than that he’s a roadrunner.

6. All action must be confined to the natural environment of the two characters — the southwest American desert.

7. All tools, weapons, or mechanical conveniences must be obtained from the Acme Corporation.

8. Whenever possible, make gravity the Coyote’s greatest enemy.

9. The Coyote is always more humiliated than harmed by his failures.

10. The audience’s sympathy must remain with the Coyote.

11. The Coyote is not allowed to catch or eat the Road Runner.

Check Jones in 1976 – by Alan Light. Jones won three Academy Awards. The cartoons which he directed, For Scent-imental Reasons, So Much for So Little, and The Dot and the Line, won the Best Animated Short.

By way of an aside, Jones thanked novelist Mark Twain for introducing him to coyotes.

I found the Coyote in the fourth chapter of Roughing It, which is a journal he wrote about traveling by stagecoach to Carson City, Nevada. During that period, he kept hold of the things he’d seen and among them were things like tarantulas, and so on. Twain opens that chapter with a description of the coyote, which is about as accurate as anybody has ever described one. He, also, humanized him. And that was kinda news to me. I hadn’t run into anything where I felt that a coyote was like a human being.

He described how the coyote dressed and so on. At the end of the paragraph, Twain wrote, “He may have to go 10 miles for his breakfast and 30 miles for his lunch and 50 miles for his dinner, and we ought to pay attention to that and give him his credit, because he does that instead of laying around home, being a burden on his parents.”

It was a new concept to my young mind, this way of humanizing the coyote’s traits. It’s a concept that stayed with me. Every year I re-read that book [Roughing It], including this year. Each time I re-read it, I find something I don’t expect. Obviously, I wasn’t looking for ideas when I was five or six years old, but I got them anyway. Mark Twain gave me the whole key to thinking that animated characters think the way we do.

And now for the main feature…

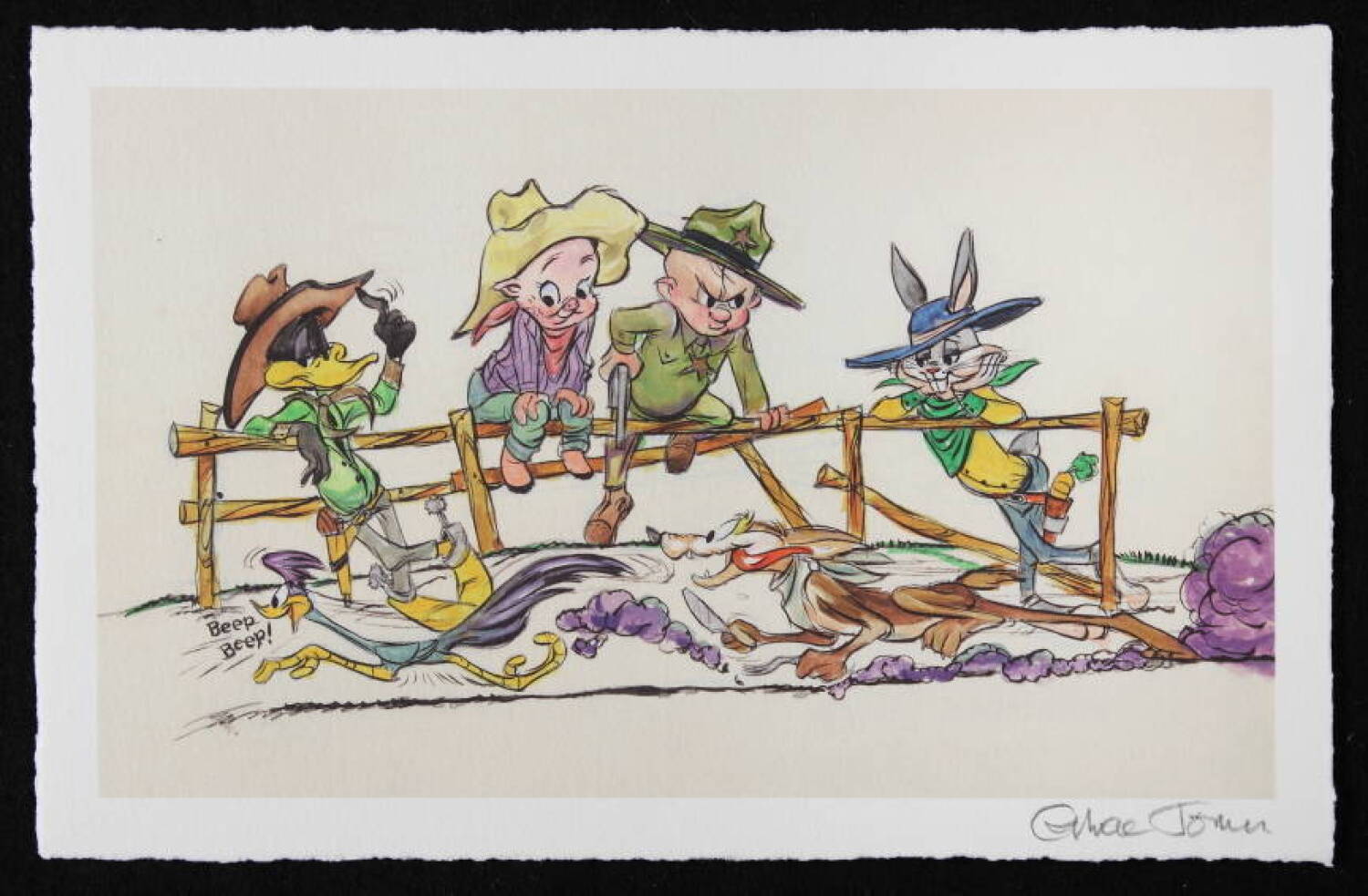

Lead Image: Warner Brothers print of Bugs Bunny, Daffy Duck, Porky Pig and Elmer Fudd in western gear, signed lower left in pencil “Chuck Jones”, via Julien’s Auctions.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.