The only advice that’s worth a damn when it comes to writing is to sit down and write. There are no quick fixes, no cheat sheets, no words that will bring around some grand epiphany. Good writing is earned from experience. It comes gradually through practice.

Asking “how to write?” and “where do ideas come from?” are the wrong questions. Only someone who doesn’t write would think these questions important – like quizzing a surgeon how he knows where best to make the incision. A writer can give advice on technique, discipline, and what to read. Books teach how good writing works.

In 1934, Arnold Samuelson read Ernest Hemingway’s short story “One Trip Across.” It inspired the 22-year-old student to travel across America and seek out the author. He wanted to ask Hemingway for his advice on how best to write.

Samuelson had just finished a course in journalism at the University of Minnesota. He harboured ambitions to be a writer. Packing a bag, he hitch-hiked his way down to Hemingway’s home in Key West. When he arrived, he found the place, like the rest of America, in the grip of the Great Depression. He spent his first night sleeping rough on a dock. During the night, he was woken by a cop who invited Samuelson to sleep in the local jail. He accepted the offer. The next day, feeling refreshed, Samuelson ventured out in the sun to search for his hero’s home.

When I knocked on the front door of Ernest Hemingway’s house in Key West, he came out and stood squarely in front of me, squinty with annoyance, waiting for me to speak. I had nothing to say. I couldn’t recall a word of my prepared speech. He was a big man, tall, narrow-hipped, wide-shouldered, and he stood with his feet spread apart, his arms hanging at his sides. He was crouched forward slightly with his weight on his toes, in the instinctive poise of a fighter ready to hit.

Hemingway asked what he wanted. Samuelson explained how he had read “One Trip Across” in Cosmopolitan, and wanted to talk with him about it. Hemingway thought for a moment, then told the youngster to come back next day at one-thirty sharp.

Ernest Hemingway and Others with Marlin July, 1934

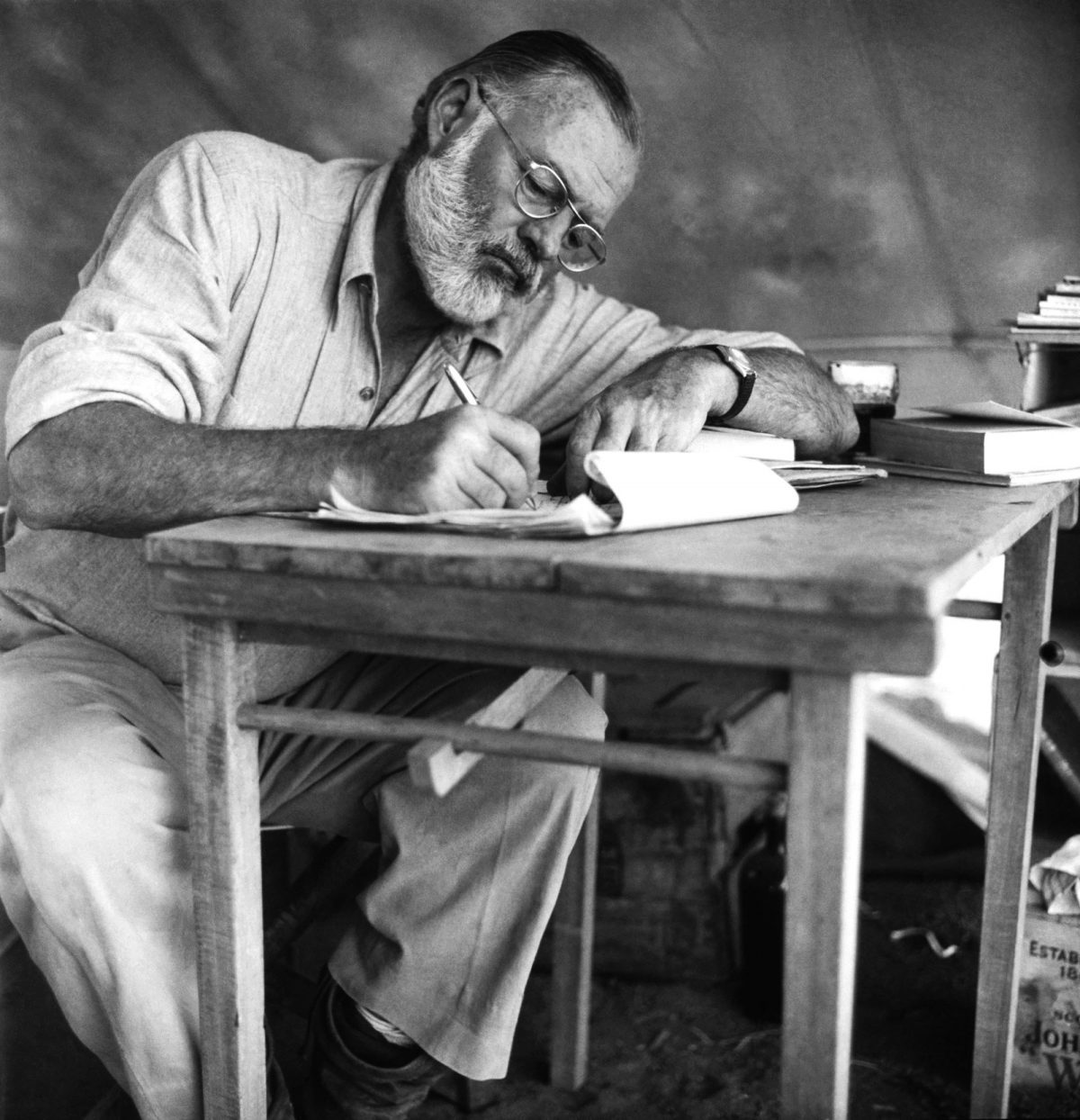

The following day Samuelson arrived early. Hemingway was seated on his porch waiting for him. They started talking about writing. Hemingway said:

“The most important thing I’ve learned about writing is never write too much at a time,” Hemingway said, tapping my arm with his finger. “Never pump yourself dry. Leave a little for the next day. The main thing is to know when to stop. Don’t wait till you’ve written yourself out. When you’re still going good and you come to an interesting place and you know what’s going to happen next, that’s the time to stop. Then leave it alone and don’t think about it; let your subconscious mind do the work. The next morning, when you’ve had a good sleep and you’re feeling fresh, rewrite what you wrote the day before. When you come to the interesting place and you know what is going to happen next, go on from there and stop at another high point of interest. That way, when you get through, your stuff is full of interesting places and when you write a novel you never get stuck and you make it interesting as you go along.

They then talked about books, Hemingway asked:

“Ever read War and Peace? That’s a damned good book. You ought to read it. We’ll go up to my workshop and I’ll make out a list you ought to read.”

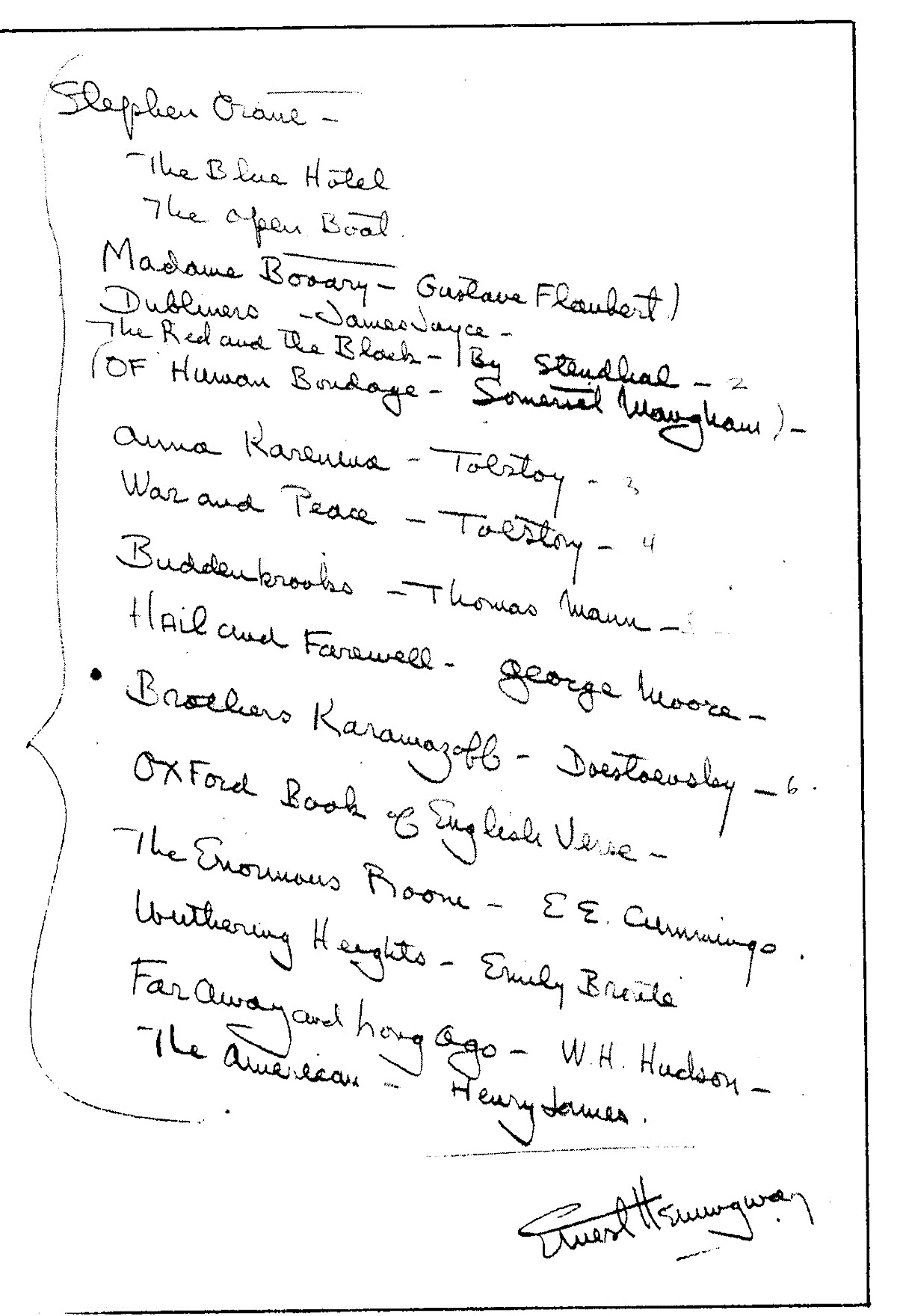

In the cool of the house, Hemingway wrote down a list of fourteen books and two short stories which he suggested a young writer should read:

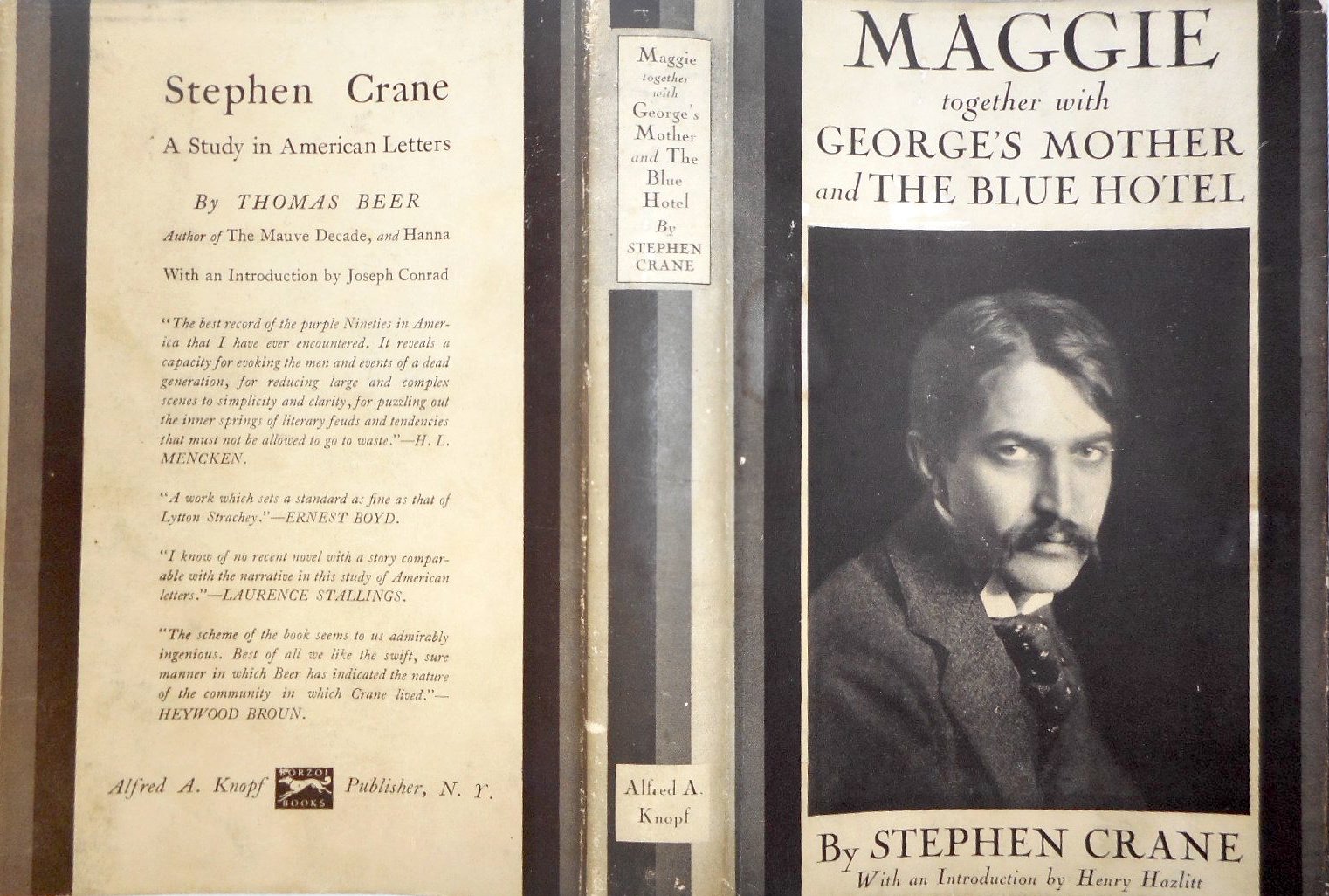

The Blue Hotel by Stephen Crane

The Open Boat by Stephen Crane

Madame Bovary by Gustave Flaubert

Dubliners by James Joyce

The Red and the Black by Stendhal

Of Human Bondage by Somerset Maugham

Anna Karenina by Leo Tolstoy

War and Peace by Leo Tolstoy

Buddenbrooks by Thomas Mann

Hail and Farewell by George Moore

Portrait of George Moore by Manet

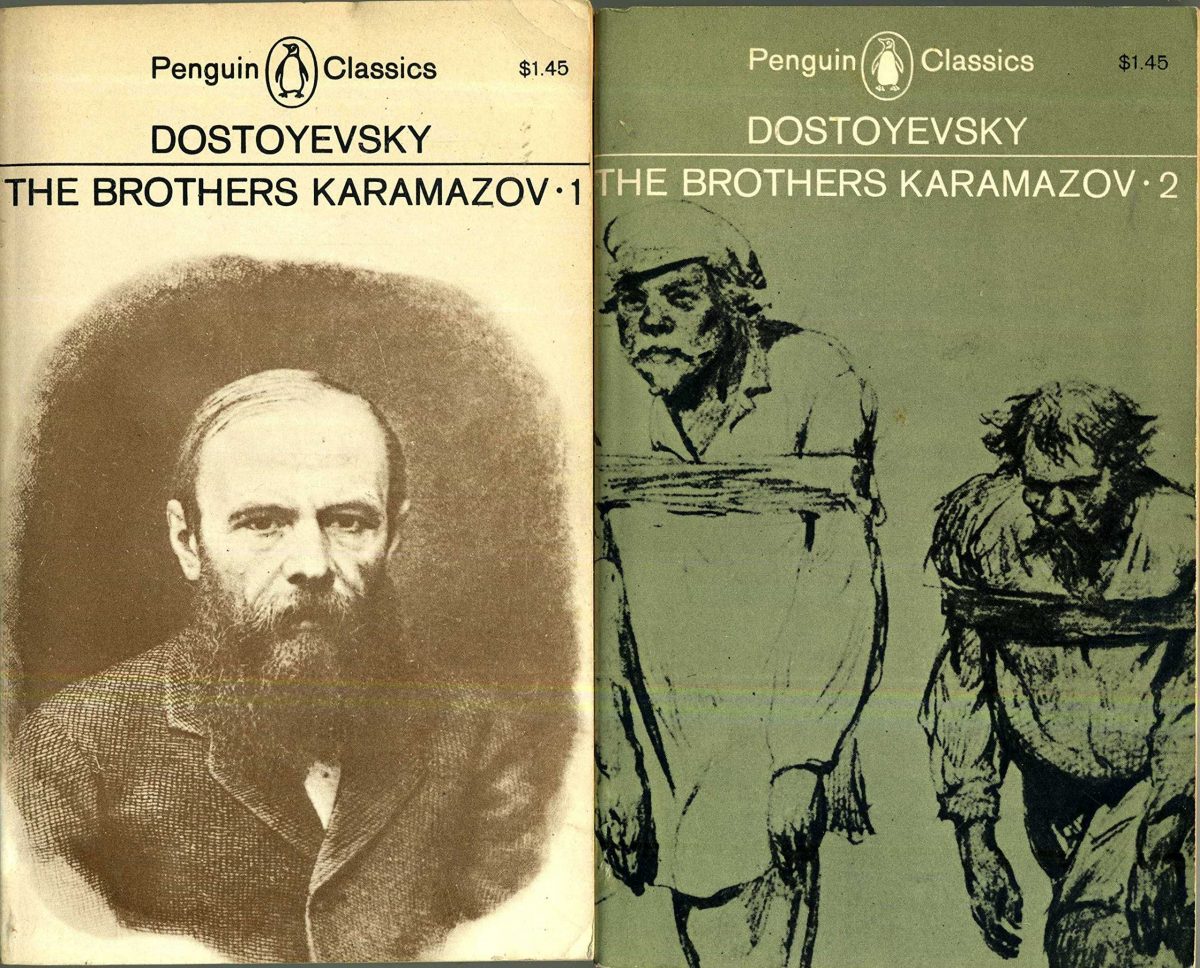

The Brothers Karamazov by Fyodor Dostoyevsky

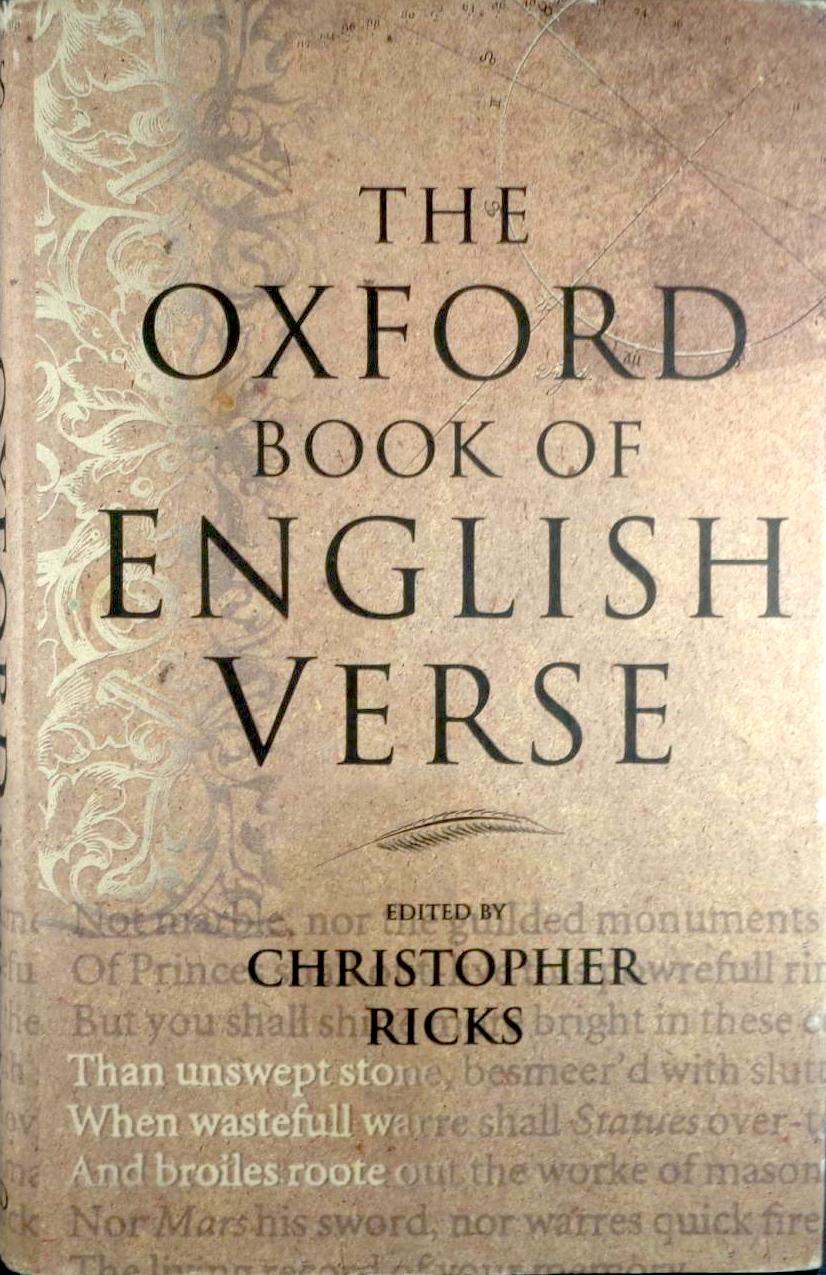

The Oxford Book of English Verse

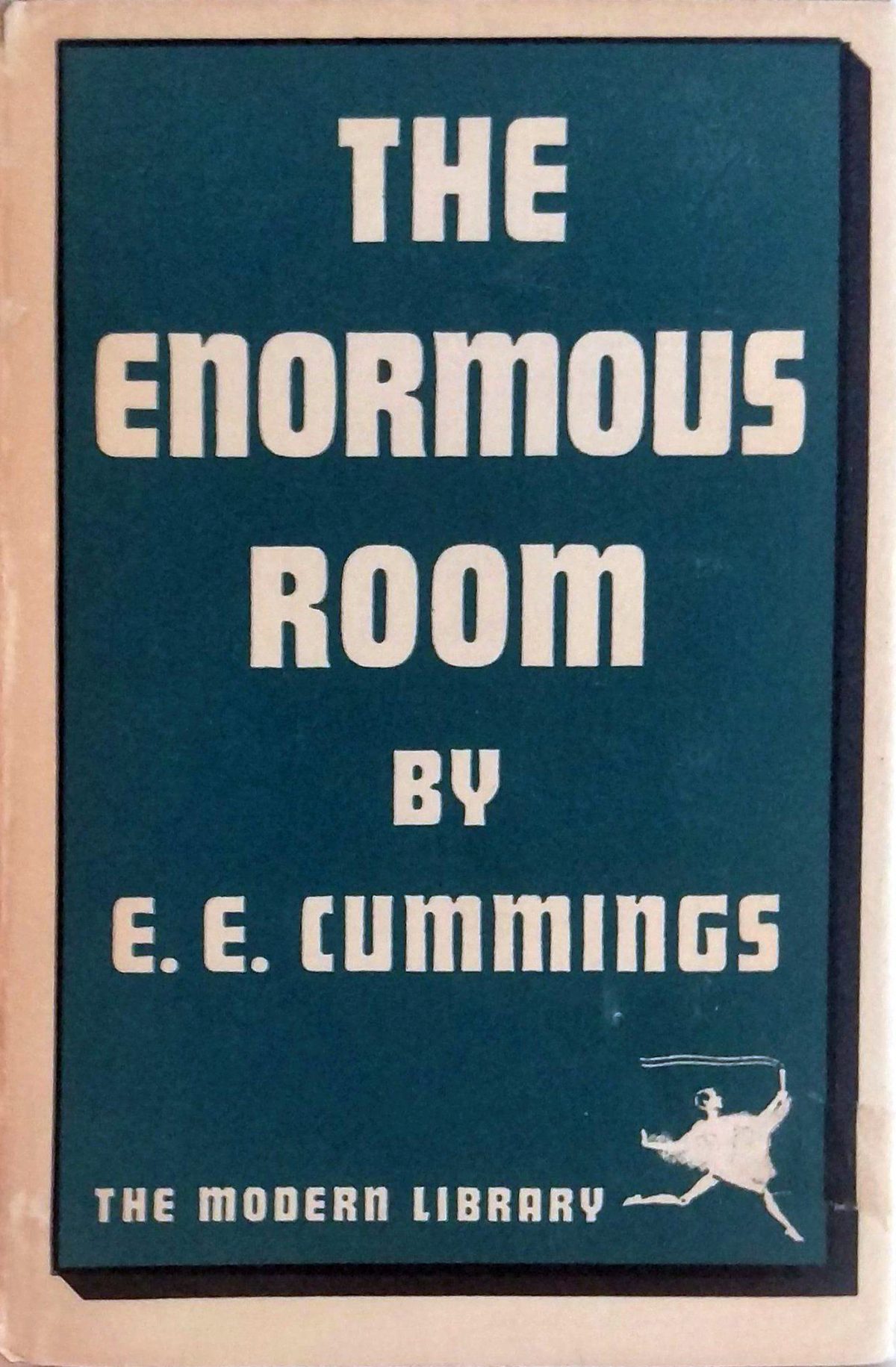

The Enormous Room by E.E. Cummings

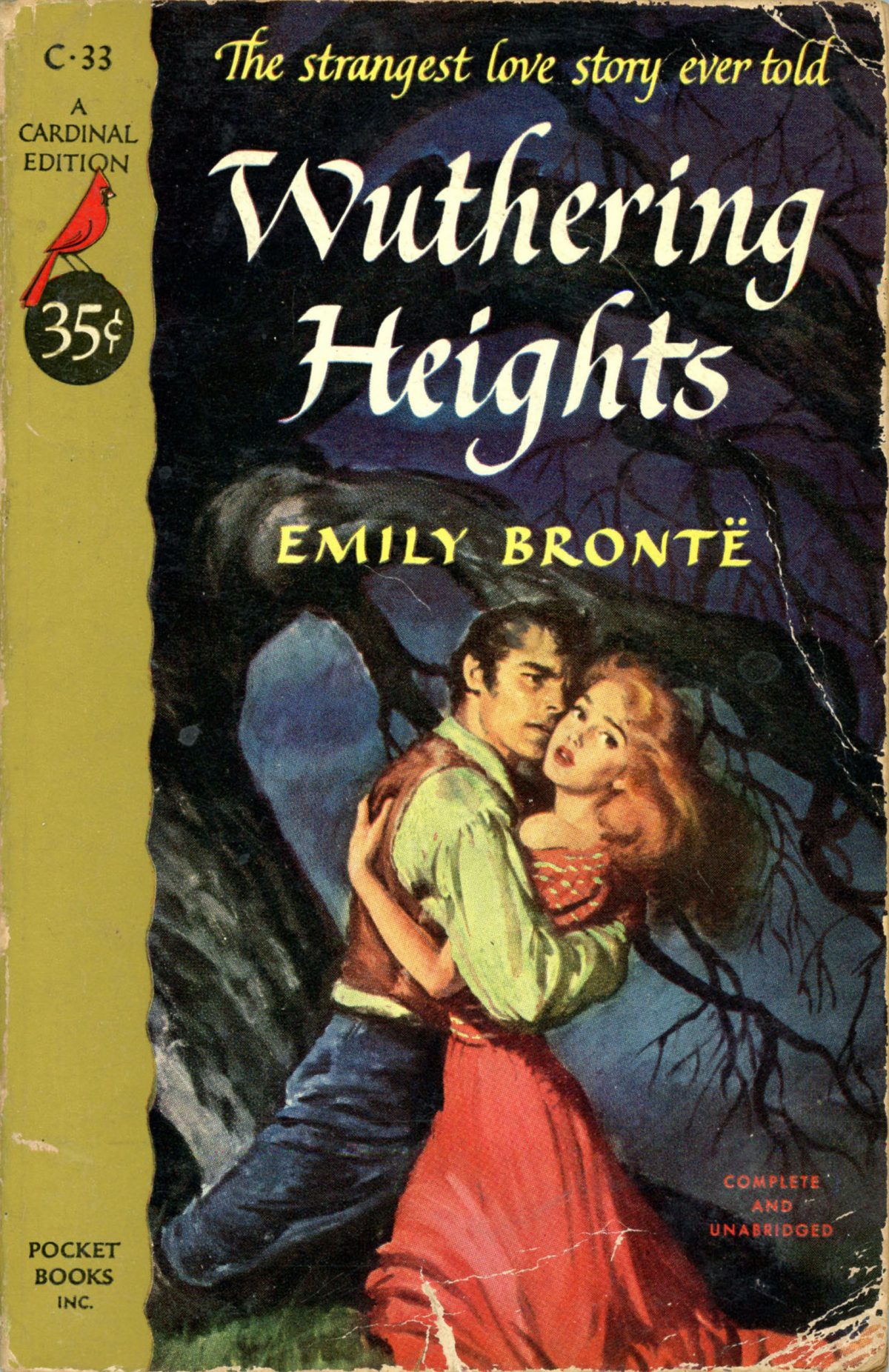

Wuthering Heights by Emily Bronte

Far Away and Long Ago by W.H. Hudson

The American by Henry James

Ernest Hemmingway Reading List

Hemingway gave Samuelson a collection of Stephen Crane’s short stories, and a copy of A Farewell to Arms. When Hemingway heard Samuelson was sleeping at the town jail, he invited him to sleep on his 38-foot cabin cruiser Pilar. He said he needed someone to keep it in good condition.

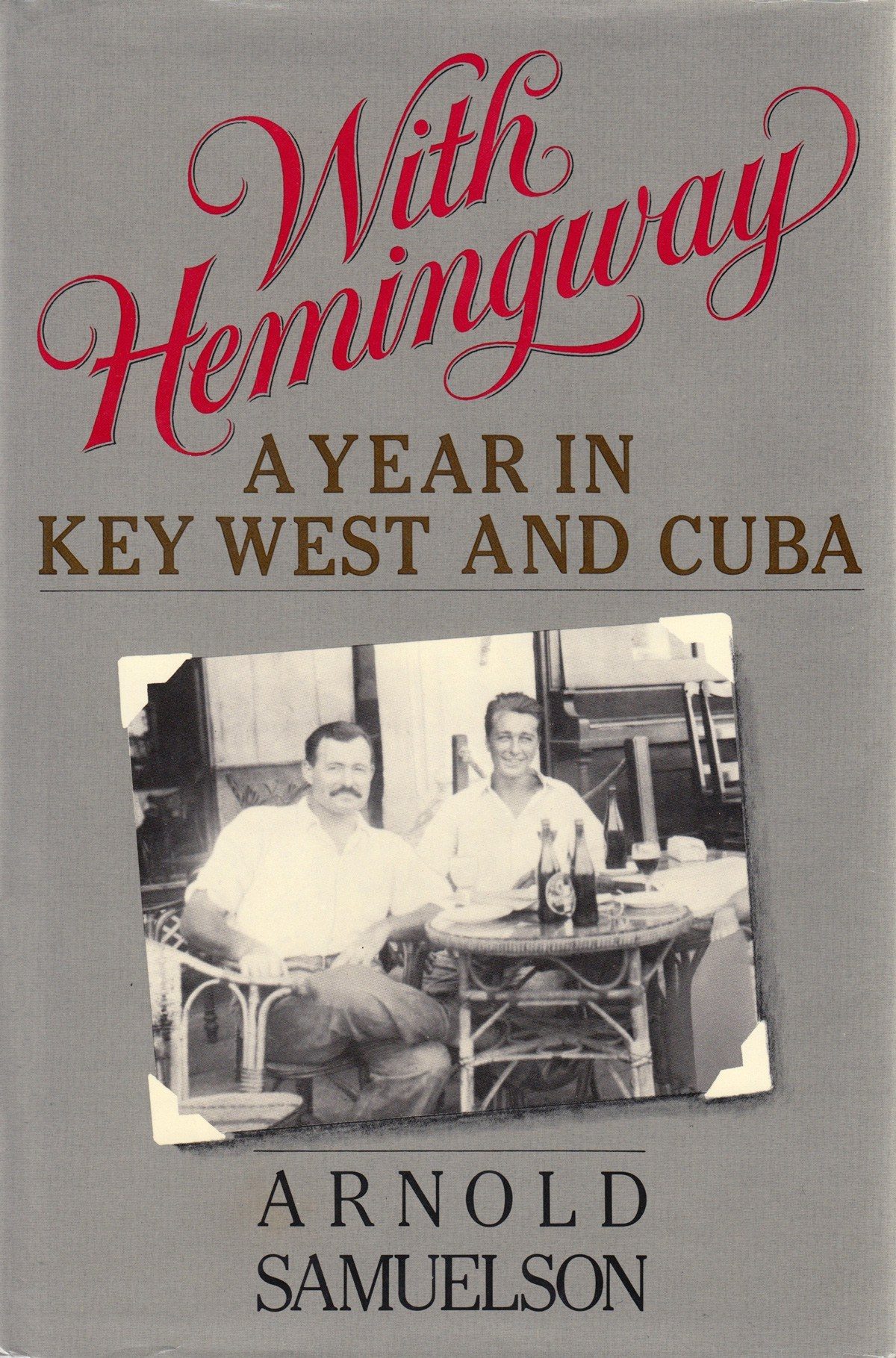

Over the next year, Samuelson worked for Hemingway, travelling with him to the Florida Keys and Cuba. He later published a memoir based on his experiences, With Hemingway: A Year in Key West and Cuba.

Ernest Hemingway posing topless with two cats, a dog and the model Jean Patchett at his ranch in Cuba for a 1950 issue of Vogue

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.