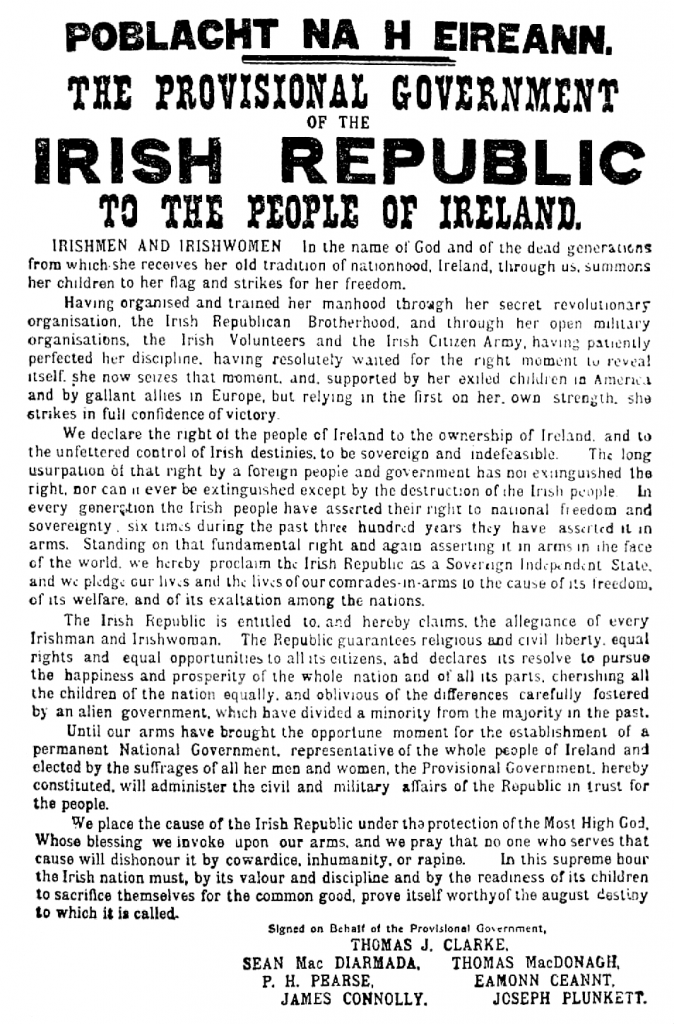

One hundred Easters ago, a band of Irish republicans stormed the General Post Office (GPO) in British-ruled Dublin and proclaimed the existence of a new republic. The Irish Republic. Padraic Pearse, one of the leaders of this somewhat chaotic rebellion against the British Empire, which at the time ruled not just Ireland but 14million square miles of the Earth’s territory and half a billion people from Africa to Asia, stood on the steps of the GPO and read aloud the Proclamation of the Republic. It was just 475 words long, half the length of a newspaper article, and it was signed by just seven men, who made up the military council of the Irish Republican Brotherhood. And yet this proclamation, this dream of a Republic, this sheet of paper and the willingness of men and women to fight to the death for it, would change Irish history and British history and impact on vast swathes of the globe. Indeed, the world is still reeling from the brilliant blow for popular sovereignty made by the men and women of the Easter Rising 100 years ago.

The Proclamation sounds as fresh and modern and radical today as it must have done to those painfully young citizen soldiers who went out to fight for it on Easter Monday in 1916. Revisionists love to slam the warriors of 1916 and the ‘terrible beauty’ they created (in Yeats’ words) for being romantic and even backward, all about making a ‘blood sacrifice’. But what is backward about the Proclamation’s guarantee of ‘religious and civil liberty, equal rights and equal opportunities to all its citizens’? Or its promise to pursue ‘the happiness and prosperity of the whole nation’ and to ‘cherish… all of the children of the nation equally, and oblivious of the differences carefully fostered by an alien Government’? Notably, the Proclamation is addressed to both ‘Irishmen and Irishwomen’; two years before British women got the vote it promised a system of government ‘representative of the whole people of Ireland and elected by the suffrages of all her men and women’. Backward? The Proclamation is a searing statement of faith in ordinary men and women, in people and liberty, in universalism and democracy; this rebellion ‘strikes… for freedom’, the authors said.

Of course, its key demand — although demand isn’t the right word; the most magnificent thing about the Easter Rising is that it didn’t demand a Republic but simply proclaimed one — is for Irish self-determination. It asserts the right of the Irish people to ‘national freedom and sovereignty’. It says that the right of the people of Ireland to the ‘ownership of Ireland and to the unfettered control of Irish destinies’ is ‘sovereign and indefeasible’. And then, the most brilliant blow, it says that the men and women who took over the GPO are now the actual government of Ireland: ‘[T]he Provisional Government, hereby constituted, will administer the civil and military affairs of the Republic in trust for the people.’ The cockiness of it all remains stirring 100 years later; its insistence of a people’s right to determine their nation’s affairs, to have a say, the say, on what happens within their country, within their borders, remains inspiring today, when sovereignty across Europe is being diluted in the name of the phoney cosmopolitanism of a new Brussels-based oligarchy.

The Republic was strangled at birth. The Easter Rising lasted for six days, after which the volunteers who took control of the GPO and other parts of Dublin, and the smaller groups who launched risings around Ireland, had either been crushed or arrested by the huge influx of British military forces. And yet its blow could not be undone. The Rising devastated the political elites of Ireland that had been negotiating with Britain for Home Rule, a flimsy, watered-down form of national autonomy, and also the prestige and authority of the British Empire itself. Launched in the midst of the First World War, the Rising unravelled the actual British state — the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland — exactly as the British state was seeking to defend its rule and authority elsewhere. And it inspired other anti-colonial movements to strike, or plan future strikes, against rule by foreign regimes. From Ho Chi Minh (then a dishwasher in London) to the emerging Indian nationalist movement to Burmese activists desiring national freedom, all were moved by the Rising and its fallout. A pamphlet handed out by Bengalis opposed to British rule was titled, ‘What Ireland has done, Bengal will do’.

Everyone quotes Yeats’ view of the Easter Rising — that Ireland was now ‘changed utterly’. But so was everything else. Britain, its Empire, the global fervour for freedom from colonialism — all of this was rattled and shaped and awoken by the six-day disturbance in Ireland and the daring proclamation of a Republic. Lenin was right when he said this ‘rebellion in Ireland’ would prove to be ‘a hundred times more significant politically than a blow of equal force delivered in Asia or Africa’. This is why much of the cultural elite in Ireland and the intellectual classes in Britain are still so physically, morally and politically agitated by the events of Easter 1916. They will never — never — forgive the Irish for what they did on that Easter Monday morning, and how they destabilised Ireland’s own political elite, the British state and the moral claims of Empire. The British can handle romantic dramas about the Indian movement for independence, and they sympathise with Kenyans who suffered terribly under British rule, and they can handle the tragic Irish figure of Michael Collins, who in 1921 signed the Anglo-Irish Treaty that partitioned Ireland. But 1916? That still fills them with dread. This week, a writer for the The Times, the establishment paper, slammed the ‘bloodstained myth’ of the Easter Rising; it was ‘an act of folly’.

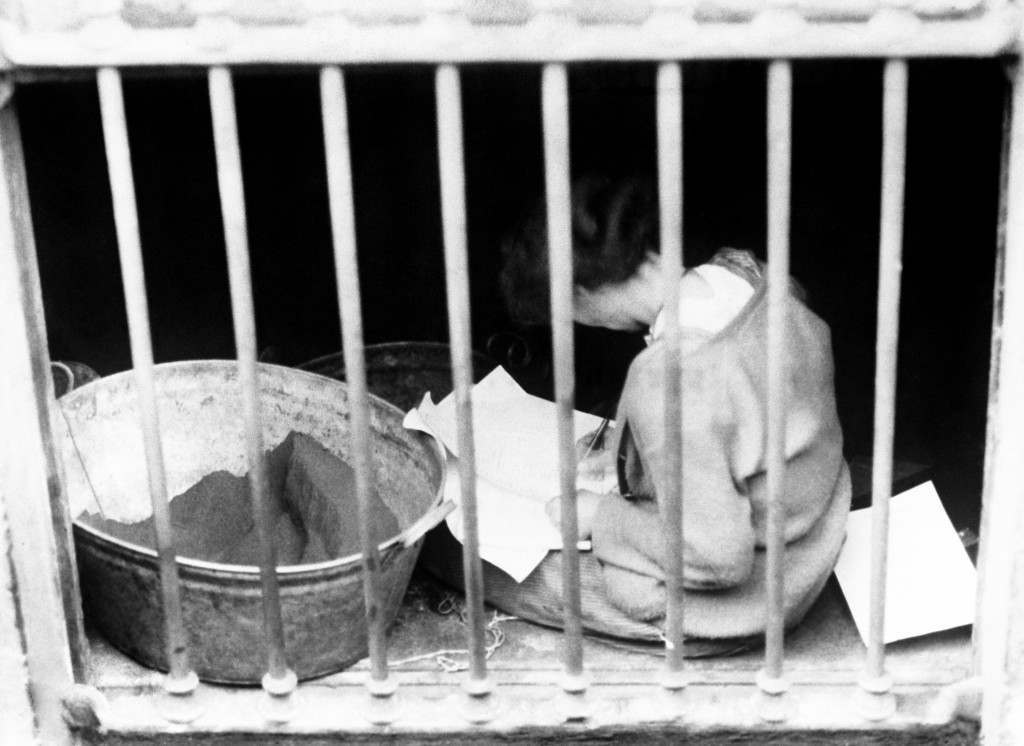

Constance Markiewicz, later known as Mrs Gore-Booth, in a prison cell in Dublin. The Countess was an Irish Sinn Féin and Fianna Fáil politician, revolutionary nationalist and suffragette. She was the first woman elected to the British House of Commons, though she did not take her seat.An active participant in the 1916 Easter Dublin Uprising she is here seen through a cellar window in Liberty hall after her surrender to the British Army.

An untold amount of military and intellectual energy was devoted, and is devoted still, to crushing the Irish Republic. If the dangerousness of an idea can be judged by the reaction it incites from the authorities and intellectuals, then the Irish Republic must surely count as one of the most dangerous ideas of the 20th century. The British crushed it first with brute force in the six days that the Rising lasted, giving rise to the Irish War of Independence in 1919 and later the Irish Civil War of 1922, and then they crushed it with Partition, which split Ireland into the 26 counties of the South and the six counties of the North, permanently destroying the Proclamation’s government on behalf of ‘the whole people of Ireland’. Intellectually, meanwhile, British and Irish thinkers have devoted an extraordinary amount of energy to delegitimising the Republic, in particular its universalism. From Conor Cruise O’Brien’s 1972 revisionist history States of Ireland, which said there were ‘two states’ in Ireland, one nationalist, one Unionist, to the current obsession with institutionalising and respecting Ireland’s ‘cultural diversity’, the Republic’s dream of ‘cherishing all of the children of the nation equally’ and ‘oblivious of… differences’ has been killed by the sanctification of separatism and sectarianism instead.

The discomfort that the short-lived dream of a Republic still evokes in the rulers of both Britain and Ireland is clear from this weekend’s commemorations in Dublin. Irish ministers pay lip service to the heroism of 1916, but their hearts, and minds, aren’t in it. As a columnist for the Irish Independent says, ‘Official Ireland’ is ‘terribly nervous about commemorating the 1916 Rising’. It isn’t hard to see why. The 26-county state of the Republic of Ireland (as it named itself in 1948, having previously been the Irish Free State) claims its moral and political authority from the Proclamation read on the steps of the GPO, and yet it has spectacularly failed to fulfil the Proclamation’s promise. This state does not govern the ‘whole people of Ireland’; and, as made clear by recent interventions by the European Union, to police Ireland’s economic decision-making, its nationhood is far from ‘sovereign and indefeasible’. The Dublin government constantly fears the exposure of the falseness of its claim to be the Republic. The two great things asserted in the Proclamation — democracy and universalism; the right of a people to govern themselves and the ideal of equality over identity — remain unrealised. The ideal of self-government is as weak today as it has been at any time in living memory, not just in Ireland but across Europe, and the ideal of universalism is now undermined, not by a sectarianism ‘carefully fostered by an alien Government’, but by the PC-sounding but deeply divisive institutionalisation of diversity in Ireland and the politics of identity everywhere.

What the Easter Rising really speaks to is that human beings are sometimes confronted by tough, deep moral choices, and how they choose to respond can determine not only their own futures but the world’s future, too. The Rising shows that, even in the most difficult circumstances, even with the largest Empire that the world has ever known lined up against you, people can make history. They can impact on global events, reclaim lost freedoms, create whole new republics and nations. Too often today, from Ireland itself, which now obsesses over how the Famine and various conflicts have ‘scarred’ the national psyche, to the Rhodes Must Fall movement, which treats black students as the unwitting inheritors of long-gone historical pains and crimes, we are told that history makes us rather than the other way round. The Easter Rising disproves this. Badly armed, not especially well organised, but driven by a deep moral conviction in self-government and freedom, these people made history; they changed the world.

British soldiers searching the River Tolka in Dublin for arms and ammunition after the Easter Rising. May 1916

The Irish Republic, this terrible beauty, this most dangerous idea of the 20th century, could not be allowed to live. It lasted six days. Military, political and intellectual elites aligned themselves against it. And yet it speaks to us still. You don’t have to be an Irish nationalist, or even Irish, to find the strangled Irish Republic inspiring. You just have to be someone who believes in self-government and freedom and that universalism is preferable to the fostering, or even worse the celebration, of petty differences between people. The dream of the Republic lives on, not just for Ireland but for all people who long to control their nation’s political affairs and their own lives, and, who knows, maybe even make history.

Brendan O’Neill is editor of spiked. Follow Spiked on Facebook.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.