ALFRED Hitchcock once remarked that every person understands fear, because everyone was once a child. “After all,” he declared, “weren’t we all afraid as children?”.

According to the authors of Monsters under the Bed and Other Childhood Fears (Random House; 1993, page 1), “childhood is a time of many fears” and children between the ages of six and twelve “experience an average of seven different fears.”

At its best and most illuminating, the horror film genre expresses fears about the future, about mortality, and about, even, how we live day-to-day. Some notable horror movies, however, have also attempted to explicitly sow terror (and indeed, melancholy…) by adopting the perspective of a child as he or she broaches change, and the onset of maturity. After all, the end of childhood is also, in many ways, the end of innocence itself.

The following five genre films masterfully express the difficulties of childhood’s end with expressionistic and haunting visuals, and thus explore, in cinematic terms, what it can mean to “grow up.”

Invaders from Mars (1953)

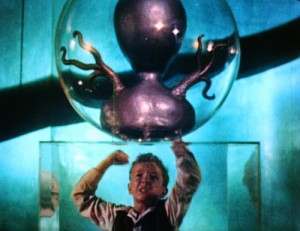

This B-movie from William Cameron Menzies concerns an American boy, David MacLean (Jimmy Hunt) who awakens one night and becomes aware of a Martian invasion. The alien invasion, not coincidentally, is headquartered out of his back yard, atop a hill. This fact immediately suggests that the threat emerges from the boy’s imagination, or perhaps from his subconscious mind.

After David attempts to convince his parents that the invasion is real, they are sucked down through a sand-pit vortex, and he loses them to the Martians. The MacLeans then return to the family house, but as emotionless drones or slaves. Their demeanor is such that it seems they have withdrawn all their love and affection from their own child.

The notion of suddenly losing the affection of your parents is terrifying enough, but the visuals of Invaders from Mars are also scary due to Menzies’ remarkable compositions, which are largely inspired by the tenets of German Expressionism. Specifically, the film’s exaggerated angles suggest a menacing, over-sized world as seen through the eyes of a child.

“Using low-angles, close-ups and outsized sets,” Paul Meehan writes in Saucer Movies: A UFOlogical History of the Cinema (The Scarecrow Press, 1998, page 50), “Menzies subtly shows the action through David’s childlike point of view.”

Not incidentally, young David also becomes the only individual who can save the planet Earth, even after he has teamed up with a Mom/Dad pair of adult scientists. This focus on the self as “hero” also is reflective of childhood, in a deep way.

Accordingly, Invaders from Mars is a “wish-fulfillment of every child’s fantasies of self-importance,” according to authors Kenneth Von Gunden and Stuart H. Stock in Twenty All-Time Great Science Fiction Films (Arlington House, 1982, page 83): “In his dreams, David is the respected friend of a doctor, a famous astronomer, and a military man. He is the one who recognizes a menace invisible to the adults around him.”

During the climax of Invaders from Mars, David learns that the invasion is indeed a nightmare. He is home safe, in bed. But as he awakes from his dream, he sees the alien saucer land in his backyard all over again, an explicit suggestion that the cycle — and the terror — will repeat.

It has not difficult, therefore to contextualize the film’s invasion as a manifestation of a child’s recurring fear that his parents don’t really love him, or could permanently withdraw their love if he displeases them. In the case of Invaders from Mars, the end of innocence is heralded by David’s lesson that love is not unconditional and that external factors can take it away.

Let the Right One In (2008)

Tom Alfredson’s Let the Right One In is the sort of horror movie that Ingmar Bergman might produce or direct: a contemplative meditation on childhood and friendship. The film tells the story of Oskar (Kare Hedebrant) a lonely twelve-year old boy who lives in a gray apartment complex in blue collar Stockholm.

Oskar’s mother is dismissive of her son’s needs (especially when something good is on TV), and Oskar’s father, an alcoholic, has all-but abandoned him. Life — much like the constant snowfall outside his apartment’s windows — seems like a never ending blizzard…of bleakness and boredom. At school, he is bullied by his schoolmates, and all that seems to penetrate Oskar’s lonely world are the stories he hears from teachers of true crime, of murder, and of death.

In a world of only gray, such color — the color of blood? — seems romantic.

Very soon, Oskar meets Eli (Lina Leandersson), a strange “new” girl in town who appears to be his contemporary but is actually an ageless, predatory vampire. When told of what she really is, Oskar doesn’t blink or blanch. In this hopeless context of loneliness and bullies, it’s actually a relief to believe in vampires.

When Eli reports that she must leave town (lest she be hunted down…), Oskar has a choice: remain “in the courtyard” as his mother orders, or take a chance and “let the right one in” to his closed-off emotional life, and try to seek some happiness.

An indictment of an adult world which fails children on every level, Let the Right One In imagines the ways that two kids might build a valuable emotional connection, even in the most difficult circumstances. They do so based on a mutual understanding of the things their lives lack: companionship, tenderness, security, and so forth.

Eli and Oskar, in the end, be monsters or become monsters, but, the film wonders if isn’t it better to have someone at your side, rather than live a life of isolation and gray. The dark cloud on the horizon is, appropriately — again — the end of innocence. Oskar will grow old, and Eli will not. She may have befriended him in the first place simply to assure that he will take care of her one day, much as another companion once did. That companion died, betrayed by Eli.

Does the same fate await Oskar?

Invaders from Mars (1986)

In 1986, Tobe Hooper remade the Menzies films of 1953, and updated the story of David MacLean (Hunter Carson) for the Reagan Era. In this iteration of the famous tale, David is termed “spaced out” by his school classmates, and it is clear he has seen one too many Spielberg blockbusters. What this film adds to the mix, then, is the idea of not just a lonely childhood, but the media-saturated childhood of the VCR generation.

Like the other films featured on this list, Hooper’s Invaders from Mars takes pain to establish that the adventure is occurring through the eyes of a child. Here, adults are depicted as contradictory and arbitrary automatons (because of Martian enslavement, again). This notion is accentuated by Hooper’s frequent use of low-angle compositions when adults feature prominently in the frame. In essence, the director films from a child’s height, frequently making the audience look up at the (imposing) grown-ups.

Developing the original’s subtext about children, this remake of Invaders concerns a boy who feels disenfranchised from his family (and school), and imagines an “invasion” as the reason that his parents are distant from him.

The Hooper film also suggests that sex — a great mystery to kids, obviously — is one aspect of his family life that keeps him from feeling close to his mother. At one critical juncture in the narrative, David witnesses his Mom and Dad walk away together — arm-in-arm — up to the backyard site of the invasion. Then, in the subterranean Martian headquarters, Mom is “implanted” (or penetrated) by a phallus-like Martian device. The idea, made literal on the screen, is that sex steals Mommy’s attention away.

At other junctures in the remake, we see David letting himself into his home, behaving as a “latch-key kid” of his generation. There is no one at home to care for him, except the TV. This situation suggests that his parents’ attention is elsewhere (on upward mobility, perhaps), and that David’s imagination is filled in with the “fantasy’ and horror he witnesses regularly on television (where Hooper’s Lifeforce [1985]) plays, despite its R-rating.

To explain the film’s subtext another way, David feels separate and isolated from his parents, who are “away” from him sharing the mysteries of sex, or the obsessions of career. Having grown up with the TV set as babysitter, David thus imagines delirious fantasies of Martian invasion to explain the reason why the adult world seems so strange.

This time, when David’s dream (or nightmare…) recurs in the film’s denouement one might even contextualize it — given the film’s commentary on television as a generation’s babysitter — as a “rerun.”

The Reflecting Skin (1991)

Philip Ridley’s uncompromising, visually accomplished The Reflecting Skin has often been compared to the films of David Lynch, and the subject of the film is, once more, the end of innocence that accompanies the onset of “maturity.”

After World War II, a child named Seth Dove (Jeremy Cooper) lives in a bleak mid-western town. He soon meets a beautiful widow, Dolphin Blue (Lindsay Duncan), who claims to be a vampire. At the same time that Dolphin and Seth encounter one another and begin a strange friendship, a series of murders occur on the outskirts of town.

Meanwhile, Seth’s older brother, Cameron (Viggo Mortensen), a war veteran, seems to be suffering from terminal radiation sickness. But Seth interprets Cameron’s symptoms, such as bleeding gums, to be a symptom of his vampiric enslavement to Dolphin. He gets this idea from a comic-book.

In the end, however, Seth comes to realize that he has interpreted the world all wrong. All the comic-books are not true, and that Dolphin is little more than a lonely, haunted woman. The source of the deaths in town is a very human (and sinister) one.

But here’s the problem. A world without vampires is also a world without magic.

At the film’s denouement, Seth discovers that there is nothing special, nothing miraculous and nothing wondrous in the world. In The Reflecting Skin’s last shot, he shouts vainly to the universe at large, decrying his involuntary initiation into adulthood. Like all children, Seth had surrounded himself in the magical cocoon of childhood, where he had imaginary friends, and the possibility of a hopeful future.

Now, he has been shunted into a much more despairing, empty place.

“Innocence is Hell,” Dolphin Blue tells Seth in The Reflecting Skin, but life “only gets worse” after it is gone. The film’s discussion of innocence’s end is also mirrored in Cameron’s subplot. A soldier, was stationed in the Pacific during World War II and must have been exposed to fall-out from an atomic bomb.

If so, The Reflecting Skin is about the end of innocence not just for Seth, but for the modern world

Phantasm (1979)

Don Coscarelli’s 1979 horror masterpiece is perhaps the most affecting of all the films featured on this list. It is the story of a boy, Mike (Michael Baldwin) who is in deep mourning over the recent deaths of his parents, and also the death of his older brother, Jody (Bill Thornbury).

Because of all the death he has witnessed, Michael constructs the “phantasm” of the movie’s title to make sense of it. Specifically, he imagines a villainous Tall Man (Angus Scrimm) turning death into an industry in his small town, and he conceives a world in which he and Jody are together, fighting a pitched battle against this angel of death.

In this world, the Tall Man — representing death — can be defeated, and life can return to normal.

Yet even in his heroic fantasy Michael can’t completely banish the specter of mortality, the constant, waking fear of being left alone. In one cleverly-composed scene, Coascarelli focuses on Mike running in the background of a frame, attempting to keep up with Jody (who is riding a bike).

But Jody, oddly unaware of his brother’s presence behind him, pulls further and further away from his desperate sibling. Eventually, Mike stands alone in the frame, abandoned, and it is clear his fear of being left alone is manifest.

“It’s Jody again,” he notes, “I found out that he’s leaving.”

Many times throughout Phantasm, Coscarelli clues in viewers to film’s nature as a child’s dream or fantasy by focusing explicitly on how young Mike sees the world. At one point, we see only his eyes as he peeks out of a half-open coffin in a mortuary. At another point, we watch him spy on the Tall Man, using a pair of over-sized binoculars.

Right to the very end, Mike tries to deny the permanence of death (and therefore the end of his innocence) but his vision is shattered once more, in the film’s finale, when the Tall Man comes for him again.

In his 2011 text, The Sociology of Childhood, author William Corsaro wrote that horror movies can form a sort of “risk management for children and youth in which they challenge themselves emotionally to deal with fears.”

Let The Right One In, The Reflecting Skin, both versions of Invaders from Mars and Phantasm may perform the same task for jaded adults. These films allow mature viewers to remember how it felt to be a kid, and they in tap into the universal fears and dreads that Alfred Hitchcock said we all faced.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.