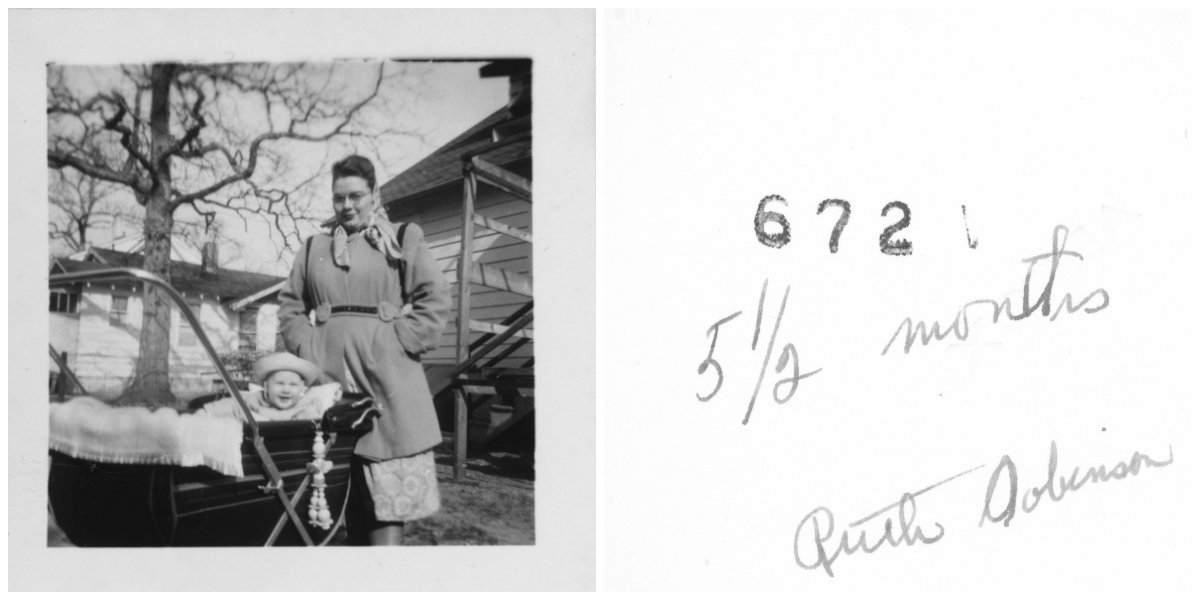

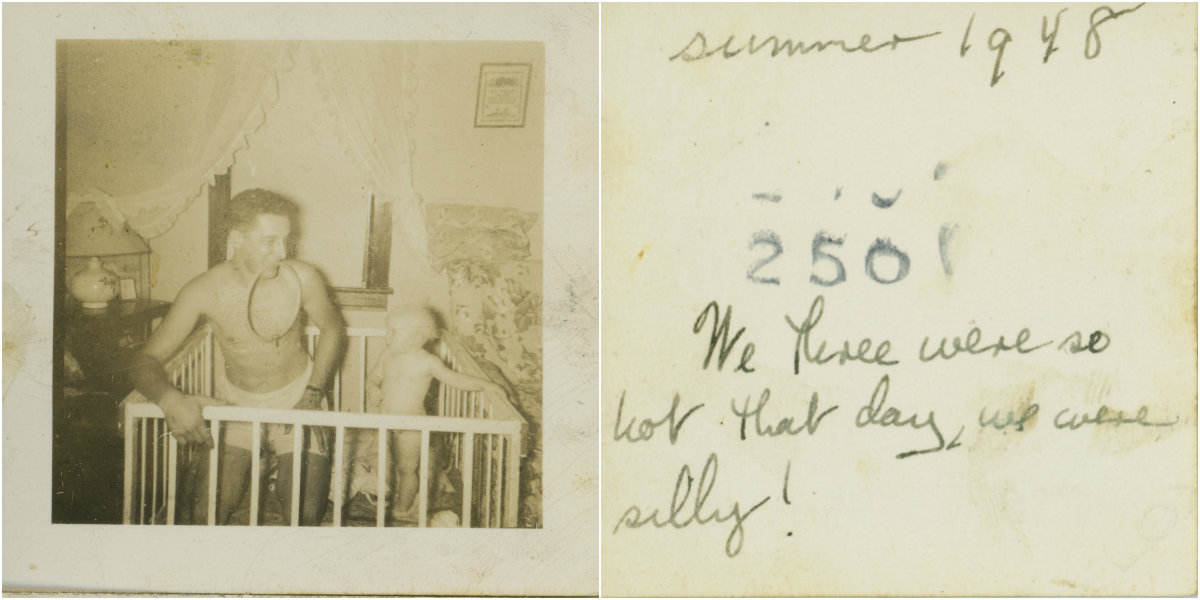

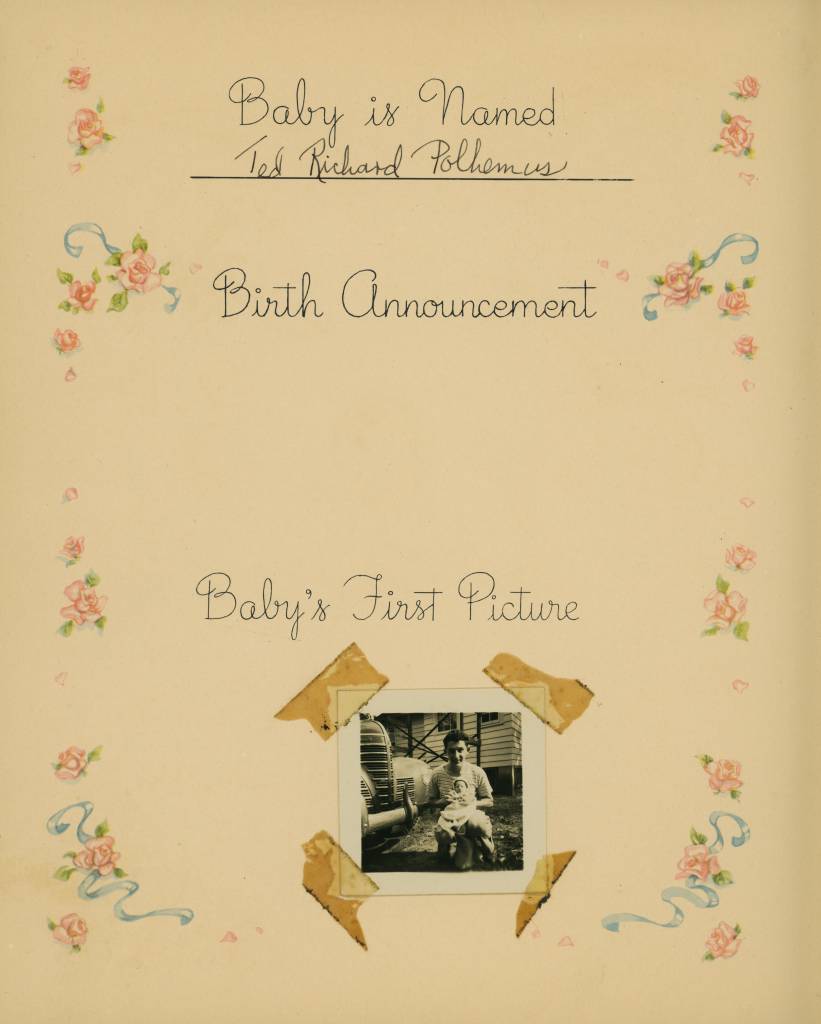

Ted Polhemus shares his personal photo archive. His life begins in the bosom of the All American, late 1940s family. Many of the photographs are from tiny 4mm photos taken by his mother and father in the mid 1940s. The family album opens in October 1947, just after Ted’s birth. The very young Ted, the first born of three, is with his father, Charles Sydney Polhemus, and mother, Peggy’ (Margaret) Polhemus, at the family’s home at 19 Oak Terrace, Neptune City, New Jersey, USA.

The album is a delightful snapshot of a time when the war was over and American families were booming. The pictures accompany Ted’s book BOOM! – A Baby Boomer Memoir, 1947-2022 – extracts from it feature between the pictures of the American dream. It tells the story of how Ted Polhemus came to be and what life was like back then in small-town middle class America, where, as John Updike put it, ‘extremes clash and ambiguity restlessly rules.’ – Paul Sorene.

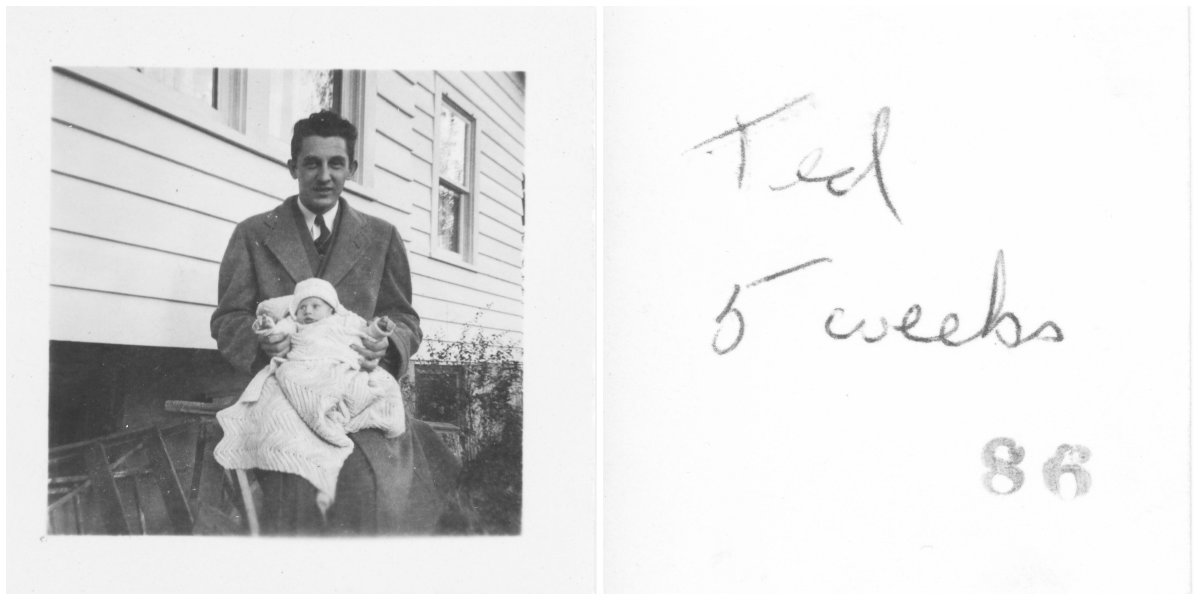

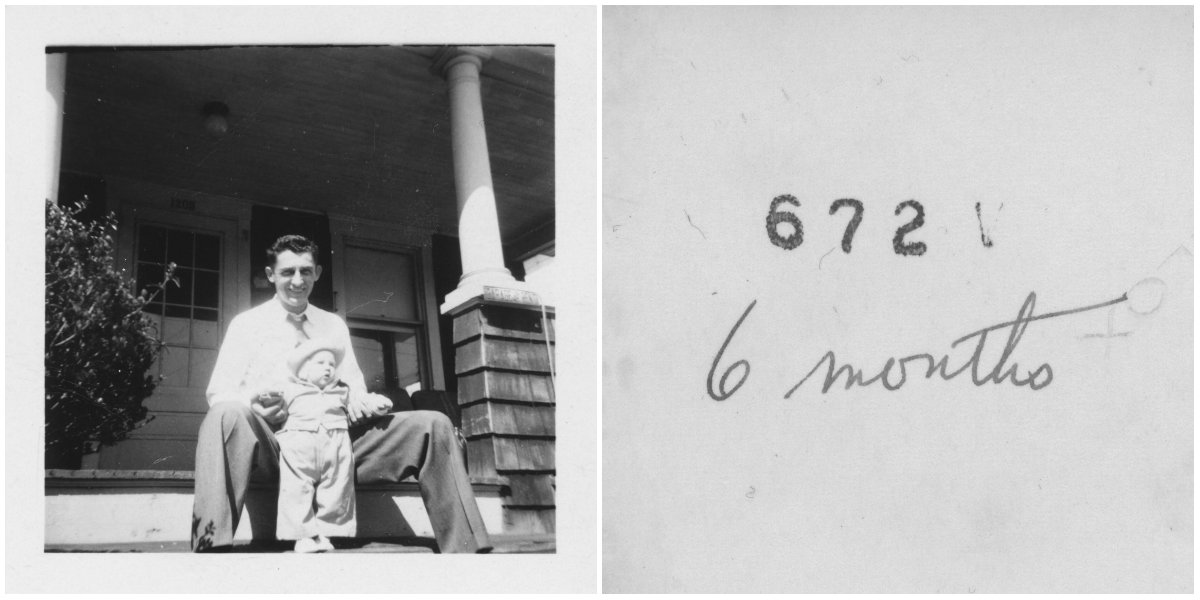

Early (5 weeks) pic of me with my father, Charles Sydney Polhemus, 19 Oak Terrace, Neptune City, New Jersey, USA

Ted Polhemus writes:

Charles Sydney Polhemus returned from Europe, the war finally over, in 1945. It had been the first time he’d left America, possibly even his first time out of New Jersey. He had ‘prayed every day I wouldn’t have to shoot anyone’ and, his prayers answered, he had seen no significant military action. Crossing the English Chanel about a week after DDay, then traveling across France, he allowed himself to be talked into celebrating reaching the Rhine with a glass of beer. (When his teetotal Methodist mother heard of this she had reportedly taken to her bed in despair that her eldest son had ‘gone to the Devil’.)

But Charles Polhemus’ celebrations had been brief: a ‘Dear John’ letter received the next day informed him that his hometown sweetheart back in Neptune City, New Jersey, had found someone else. Contrary to his normally frugal character (and certainly unaware of any Wagnerian symbolism) he threw his gold engagement ring into the Rhine.

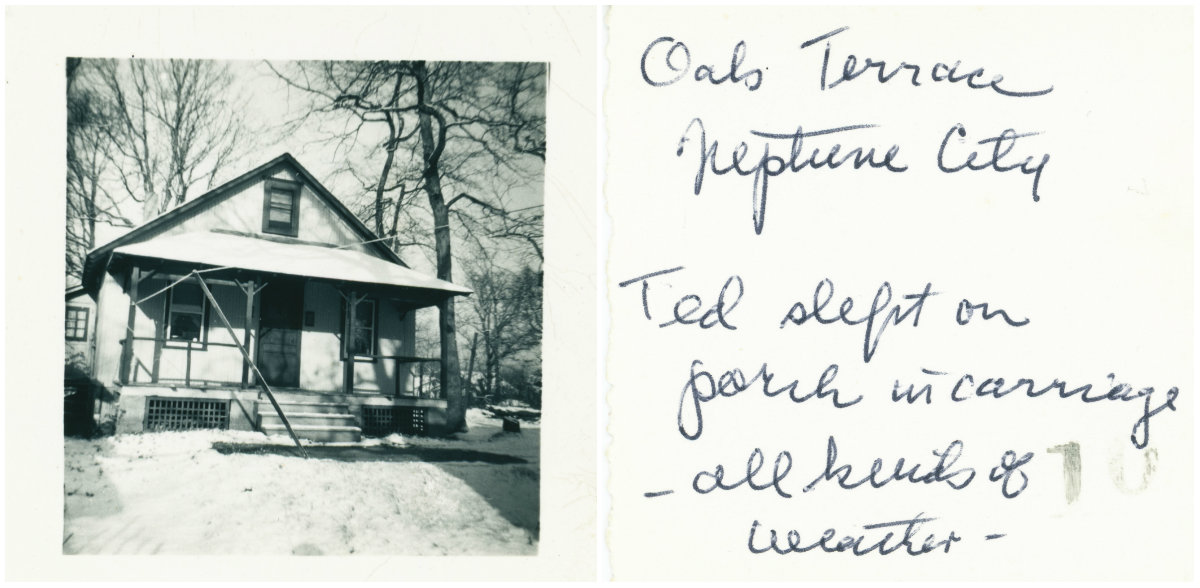

The Neptune City, New Jersey, USA to which Charles Polhemus returned was little changed from the one he left behind some three years previously. A double misnomer, this community of some two or three thousand souls was actually a town rather than a city and, located about one mile from the sea, wasn’t quite the Roman god’s watery domain. While Neptune City’s Main Street – Corlies Avenue – boasted a couple of multistory buildings, and while a rightangled, numbered grid of streets suggested that the town’s founding fathers had anticipated a certain degree of urbanity, in truth, Neptune City had developed mostly as single story ‘bungalows’ – typically, rectangular in shape with the smaller side, featuring a porch, facing onto the sidewalk and the road.

Compared with the neighboring seaside resort towns of Asbury Park, Ocean Grove, Bradley Beach, Belmar and Avon – down the ‘shore’ where, according to Tom Waits, ‘everything’s alright’ – Neptune City had quite a low population density. Yet its homes were, nevertheless, tightly packed together compared to the even less populous ‘suburbs’ which would soon mushroom up on the once agricultural land to the west of Neptune City.

With my parents Charles and Peggy Polhemus in the backyard of my mother’s parents’ home in Interlaken, New Jersey, 1947-8

Born and raised in a two room ‘shack’ on the corner of Corlies Avenue and South Main Street (later, the same corner where his younger brother Doug would have a Gulf gas station), Charles Polhemus – ‘Charlie’ – had attended Neptune High School just a stone’s throw away from his home where, over six foot tall, he excelled as a basketball player and was (according to women of his age one would encounter, years later, in the supermarket) ‘the best dancer in town’.

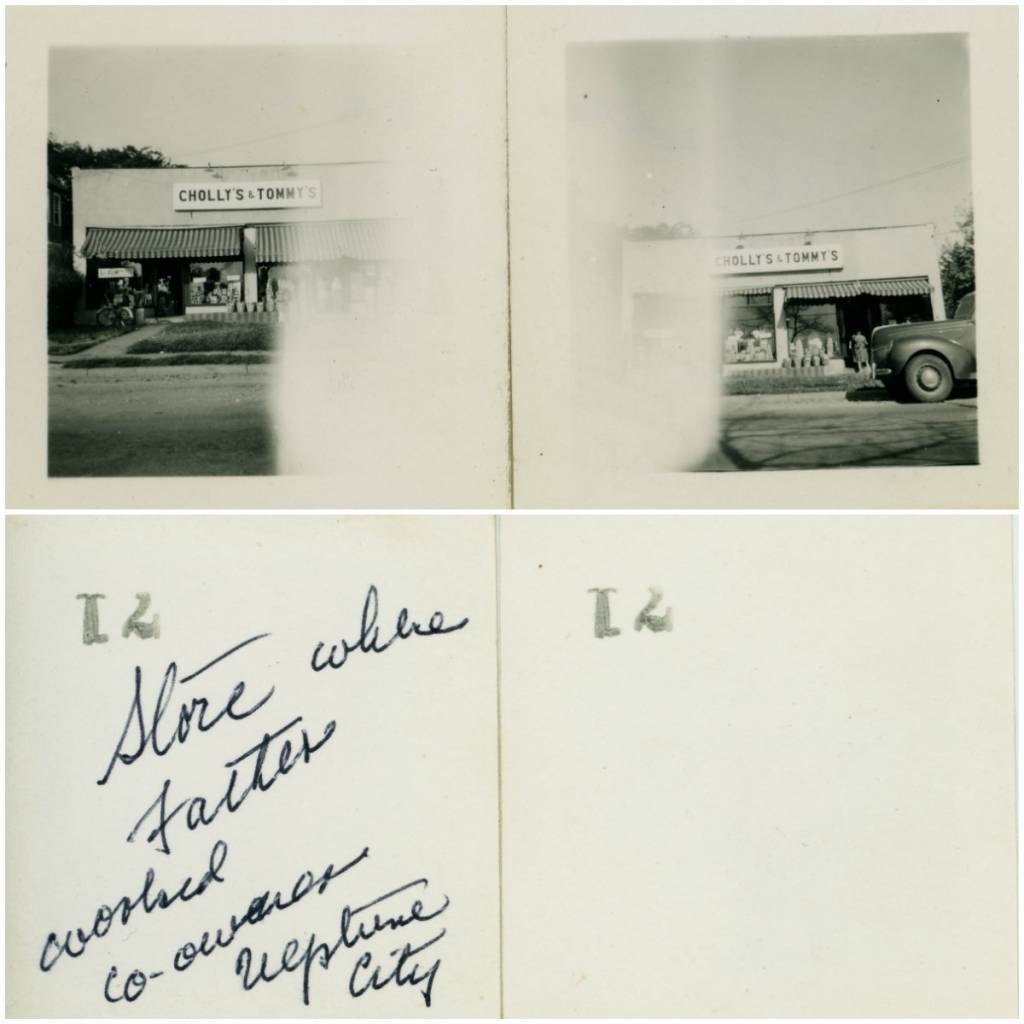

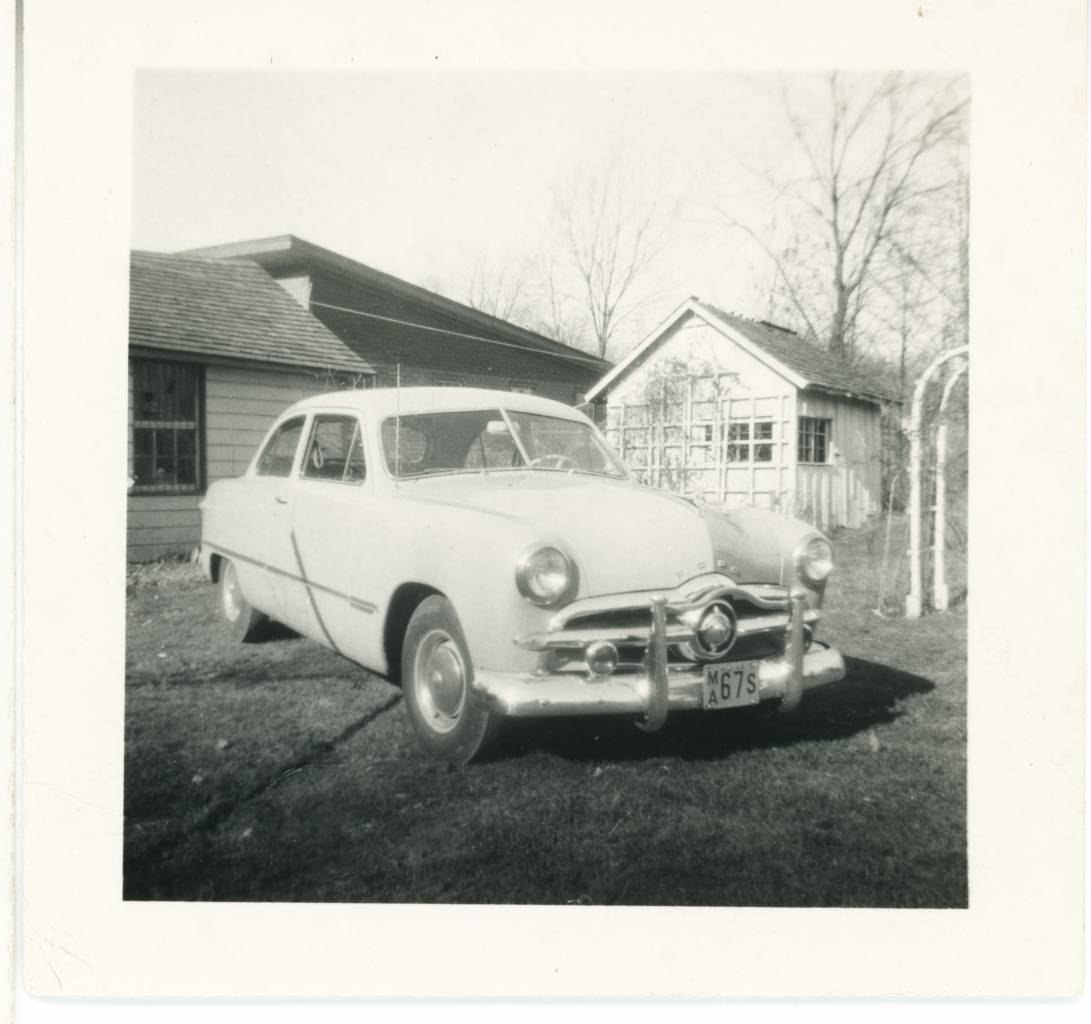

Back from the war, having survived it and with a little money in the bank, he bought himself a second hand but slightly flash car (a 1939 Plymouth with an extra, showy ‘over-rider’ bumper fitted; the same car Philip Marlowe would drive in the 1946 film of The Big Sleep) and a half share in a corner shop in the heart of Neptune City – just across from where his parents, now a step up from the ‘shack’, had bought themselves a bungalow. In Philip Roth’s Sabbath’s Theater, the narrator Sabbath and his older brother Morty grow up in the years before WWII on McCabe Avenue in Bradley Beach, about a twenty minute walk from the ‘shack’ where Charles Polhemus, my father, was himself growing up at that time.

Although slightly younger, Jewish (as opposed to my father’s strict Methodist) and in Bradley Beach rather than Neptune City, the life of these two fictional brothers would have been similar to that of my father and his younger brother Doug. A life where most people knew one another. Where you could walk to the bank, the corner shop, the beach or to visit in each others’ homes. Where you might sit on the porch watching the world go by whilst sipping a cold root beer and, on a Saturday night in summer, music blaring from a radio or a jukebox, despite what the Methodists might say, there could be dancing in the street.

This was a world where men like Sabbath’s uncle Fish sold vegetables on the street from a push cart, where pretty much anything an ordinary person needed could be bought just down the street (or by mail order from the Sears, Roebuck and Co. Catalog). Crucially, unlike the less populated, sprawling suburbs, which would start to push back inland in just a couple of years, this was a world on a human scale where for most people it was nice but not actually essential to have a car.

One Sunday morning in 1945, as he had done every Sunday morning since returning from the war, Charles Polhemus, together with his parents and his brother Doug (also just returned from the war, the Pacific in his case) went to the Memorial United Methodist Church over on West Sylvania Avenue. As the regular minister was on his summer holiday, the service that day was conducted by the recently retired Rev. Joseph Wardell Chasey who, once the Methodist Bishop of New York State, had recently moved down the shore to the upmarket neighborhood of Interlaken just north of Asbury Park (Rev. Chasey having done very well with his Bell Telephone shares bought soon after the company was formed, and held onto through the depression when many less secure would have had to sell up).

Accompanying Rev. Chasey were his wife Carrie and his younger daughter Margaret – known as ‘Peggy’ – who was in her final year of a liberal arts education at Douglas College in northern New Jersey. Blonde, attractive, bright, Peggy Chasey had the year before met and fallen in love with a young teacher at her college, who was Mr Right in all regards except one: he wasn’t Methodist. Submitting reluctantly to her father’s wishes (and, arguably, tragically because, if the truth be known, she would carry a torch for this man throughout her life), Peggy Chasey said no to Mr Right and, now in 1945 sitting in the congregation of the Memorial United Methodist Church, her eyes met the young, handsome, ex-GI Charles Polhemus who, while working rather than middle class like herself, was Methodist to his core. The couple were married in the same Church (the bride’s father presiding) and I, the eldest of what would be three children, was born October 11 1947 – the second year of the baby boom in America.

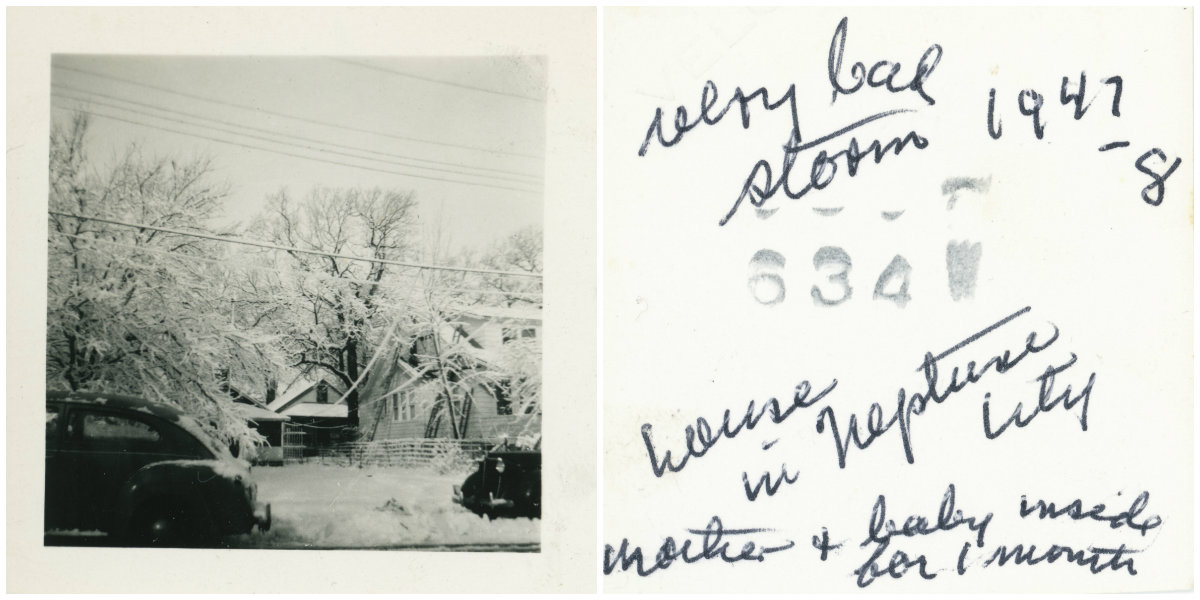

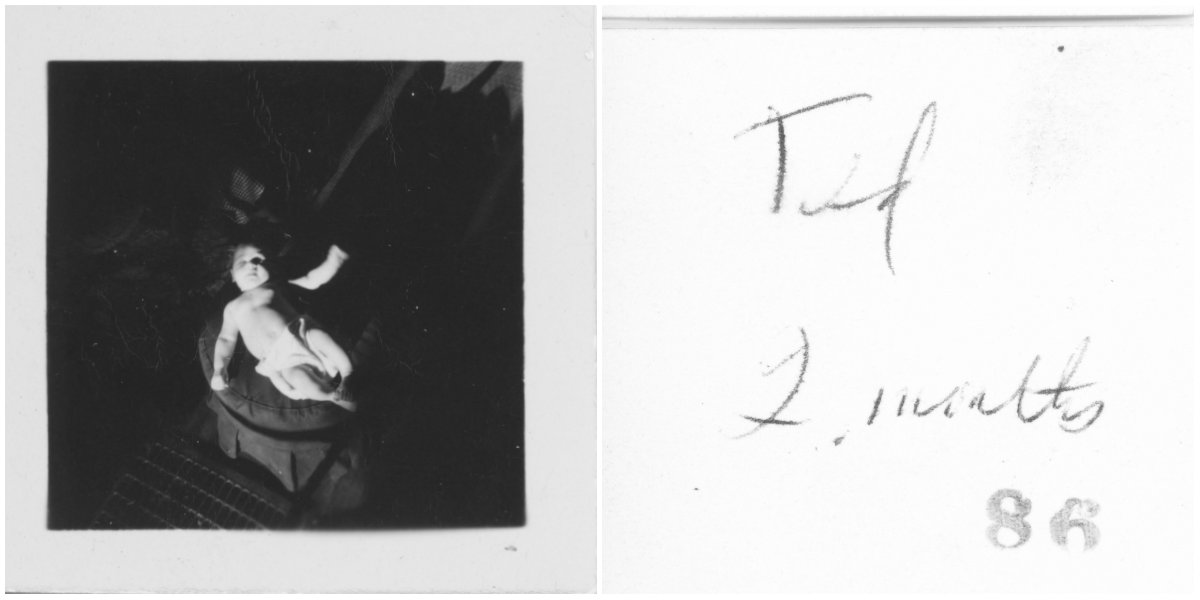

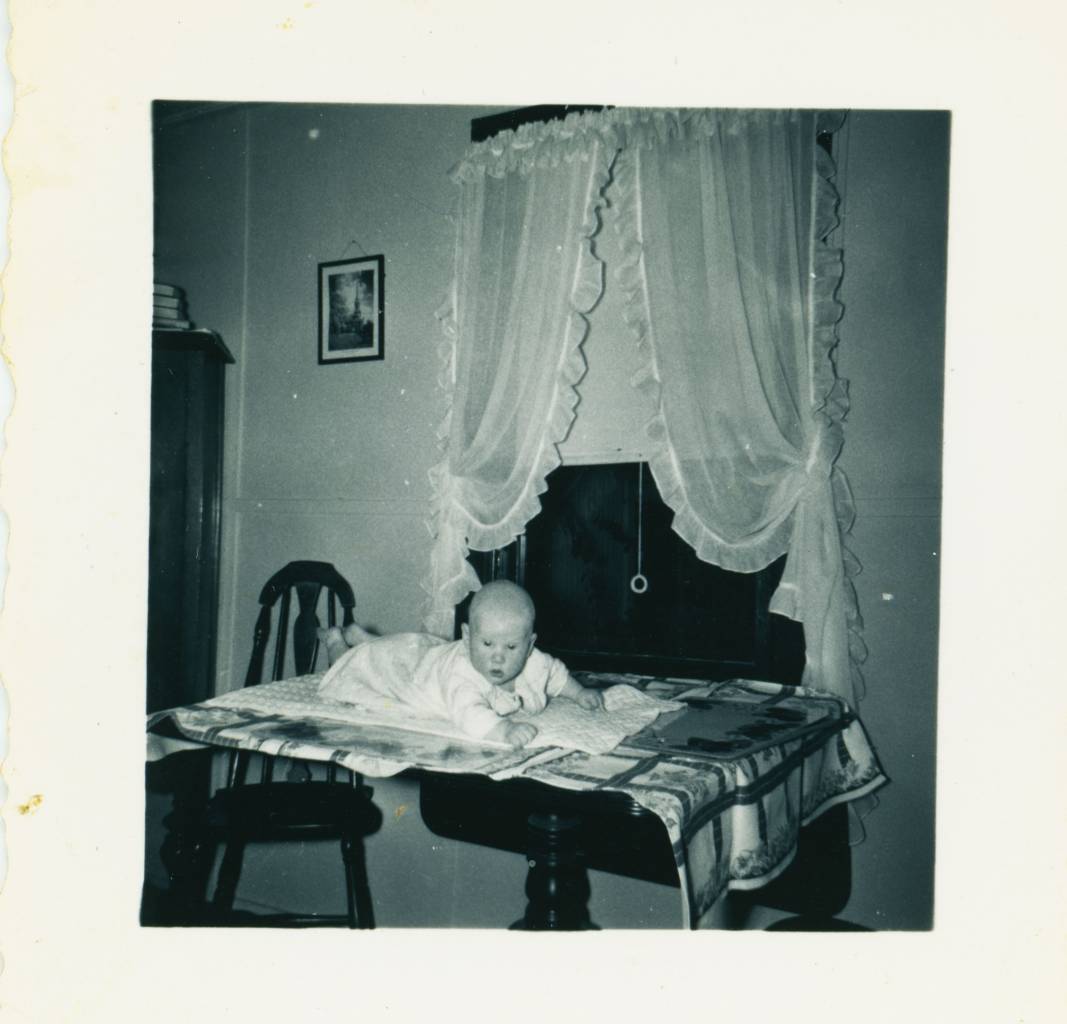

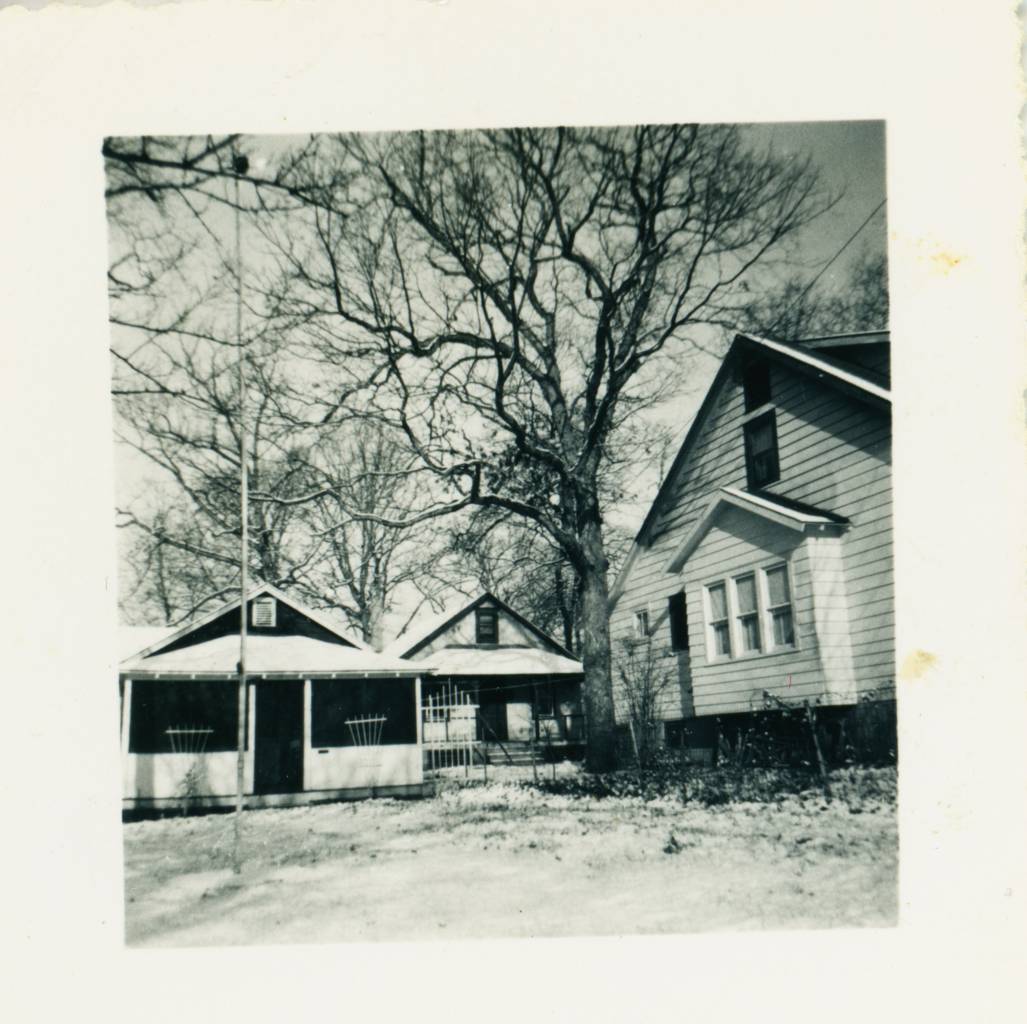

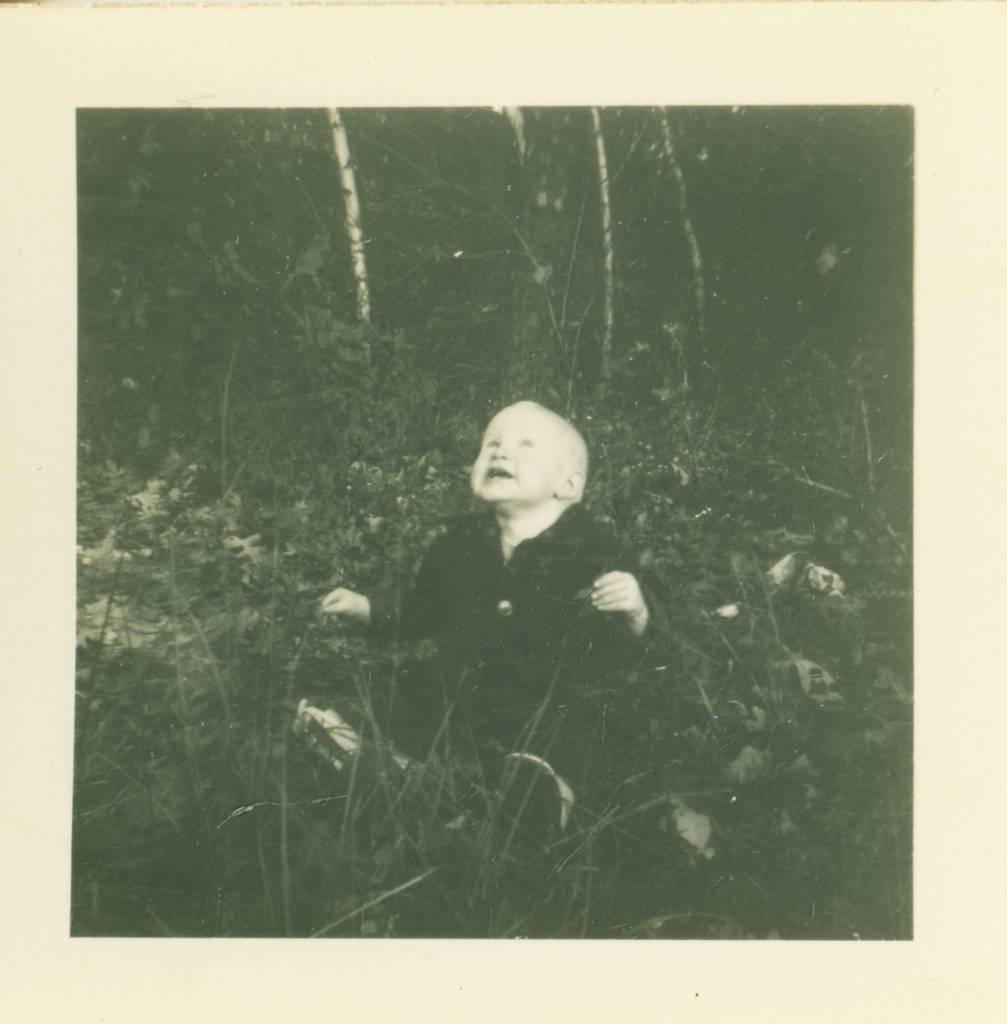

For the first four years of my life my parents and I lived on Oak Terrace, a few blocks away from the church where my parents had been married and, in the other direction, a few blocks from my father’s corner store and his parents’ bungalow. 19 Oak Terrace was also a bungalow, also a rectangle with its shorter side fronted by a porch and facing onto the sidewalk and street. Although my memories of this period are dim, if not actually non-existent, tiny 2”X” B&W photos suggest a happy, All American, late 1940s family.

While hardly luxurious, at least in retrospect, the bungalow at 19 Oak Terrace would seem to have offered a reasonable life for a young, post-war couple: the mother able to push her child’s pram to the shops, the bank, the hairdresser or to visit with a relative or neighbor. Children and teenagers could have a level of independence without any need to get their parents to drive them everywhere. If, unlike my teetotal parents, an adult wanted to go for a few beers in a bar, he (perhaps not she but my father’s Aunt Charlotte told me privately that she enjoyed a cocktail at ‘The Green Parrot’ on Highway 33) could have avoided drinking and driving by simply walking home. By today’s standards, Neptune City and thousands of other small towns like it scattered across America, were ecologically and sociologically sensible communities. The intriguingquestion then is why, as my family would do in the early ‘50s, millions of young American families turned their backs on towns like Neptune City – the home towns to which these GIs had triumphantly and optimistically returned after the war – and gravitated to new, land hungry suburbs?

The obvious answer to this question is that, given the ever swelling ranks of the Boomer babies, there simply had to be more and larger homes and it was probably cheaper and more straightforward to spread out beyond the gridded town limits rather than to rebuild higher within existing communities. So, like a lot of things, this suburban sprawl (which in the 21st century – the gas running out – disadvantages America with what looks increasingly to be a dysfunctional infrastructure) is the Boomers’ fault. But there are other factors to be considered. Firstly, it could be said that, even before the outer spread of the suburbs, America’s small towns – its fundamental social unit since its founding – were in decline.

The key problem was what was happening on and to Main Street USA: as in the case of Neptune City’s Corlies Avenue. As well as serving as the heart and central focus of those who lived in the town, Main Street USA was also the highway used by others to get from A to B. In Neptune City’s case, its Main Street, Corlies Avenue, was also the final half mile of Route 33 which runs all the way across the state to the capital Trenton. This would be great for Uncle Doug’s gas station on the corner of Corlies and South Main Street, but it simultaneously turned Neptune City’s heart into a thoroughfare – in the process, slicing the whole town in half; making it a bit of an ordeal to amble from the barbershop over to the bank and have a nice chat with whoever you ran into on the way.

With my father’s mother Nancy Allgor Polhemus in front of my father’s parents’ home at 1205 9th Ave, Neptune City, New Jersey, 1947

And, across America, long before the GIs had started to return home and the baby boom kicked off, Main Street USA, as well as functionally dividing rather than unifying each community, looked shabby and aesthetically dispiriting. Unlike in Britain and Europe where telephone and electricity companies would more often than not be obliged to take the more expensive option of burying cables underground, small town America always bristled with slightly off perpendicular telephone poles and main street was usually no exception. Nor was it seen as properly American for town planners to make any effort aesthetically to coordinate and control the look of its town centers which, accordingly, were only rarely glimpsed in the paintings of Normal Rockwell, who could more easily accommodate his cozy American Dream in nostalgic interiors or idyllic natural settings.

What you had instead, to take Corlies Avenue as an example, was a bank which rose two or three stories high with an impressive stone facade on its front while, on its sides, presumably in anticipation of the multistory structures which would be built to either side, its walls were naked, cheap looking bricks – giving the impression of architectural fraud and deceit. And, as the years rolled on and it became increasingly clear that this bank would never, ever have any company or support on either side, this lone building became a poignant symbol of the long gone dreams of Neptune City’s future.

After returning from Europe as a GI in WII, my father (Charles Polhemus) went into partnership with another ex-GI from Neptune (‘Tommy’) in a local grocery shop in Neptune City, New Jersey, USA – only a block or two from where his parents lived on 9th Ave. News to me that Charles was known as ‘Cholly’. A few years later my father quit this work on the grounds that he refused to agree that they should open on Sunday and in time became a truck driver.

Architecturally, even in the immediate post-war years before the shift to the sprawling suburbs of greater Neptune would forever destroy Neptune City’s future as a town center, the mostly one-story buildings which jostled for position along the length of Corlies Avenue were what we would today describe as post-modern in their inability to coalesce into some sort of single aesthetic pattern: here a traditional style barber shop unchanged for fifty years, there a dry cleaners effecting an air of modernity, here a would-be grand bank, there a pool hall (yes, right here in Neptune City) with tattooed, no good punks leaning on their bikes outside, here a police station and jail badly in need of a new coat of paint. The only consistency in the regular but slightly akimbo spacing of the telephone poles.

Increasingly dysfunctional owing to ever more, ever faster through traffic, ugly, hodgepodge, aesthetically unappealing, small town America’s Main Street ceased to be a place which could be celebrated by a Norman Rockwell or any of his advertising illustrator imitators – and, in a very real sense, despite its lingering iconic resonance, became largely invisible in America’s vision of itself. My father had grown up right there on Corlies Avenue, he must have known every inch of this center of his town, but with a second child on the way and – having sold his share in the corner store because, he said, he didn’t want to be involved with a shop open on Sundays – a new job driving a truck for the Keebler Biscuit Company, he seems to have had little hesitation about turning his back on his community and heading out a few miles inland to what, at the time, was mostly small vegetable farms (New Jersey being ‘The Garden State’) or uninhabited, unused, left-to-nature land.

In the great American tradition, my father, my mother and I were – literally – heading West. Frontier explorers. With less than half the population density of the old communities like Neptune City, the new suburbs in greater Neptune and elsewhere across America heralded the first Space Age: the GIs who had mile by mile reclaimed the territories of Europe and the Pacific, now, with their wives and growing families, laying claim to bits of land they could call their own. Space. MySpace. It might, in my father’s words, be only ‘postage stamp size’ but it would be his own postage stamp sized bit of space, of territory.

When you look at Neptune’s suburbs on Google Earth today what you see is some pretty big postage stamps with mostly one floor, low level but long buildings – the long part of the rectangle now, luxuriously, running parallel with the road – positioned with plenty of lawn to the front and the back. Multiplied by millions of similar suburban dwellings across America – most initially fueled by the demographic time bomb of the Boomers – this exodus from the cities and the towns spread an entire country out horizontally as had never happened before. Elbow room. Space for the kids to grow up. But all of it, as never before in human history, making an entire, vast country dependent upon the motor car and affordable gas. (England’s earlier development of suburbs in the 19th and early 20th centuries being structured around and deriving from the spread of the train and the underground railway.) But the black gooey stuff was just bubbling up from the ground in Texas and California in the ‘40s and ‘50s, so no worry.

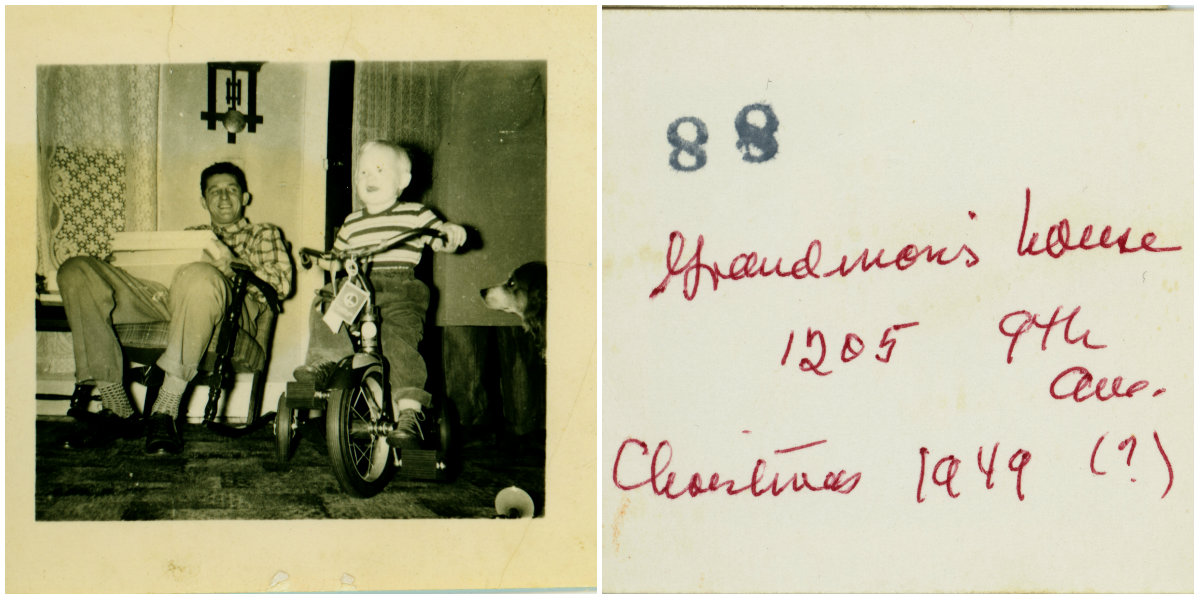

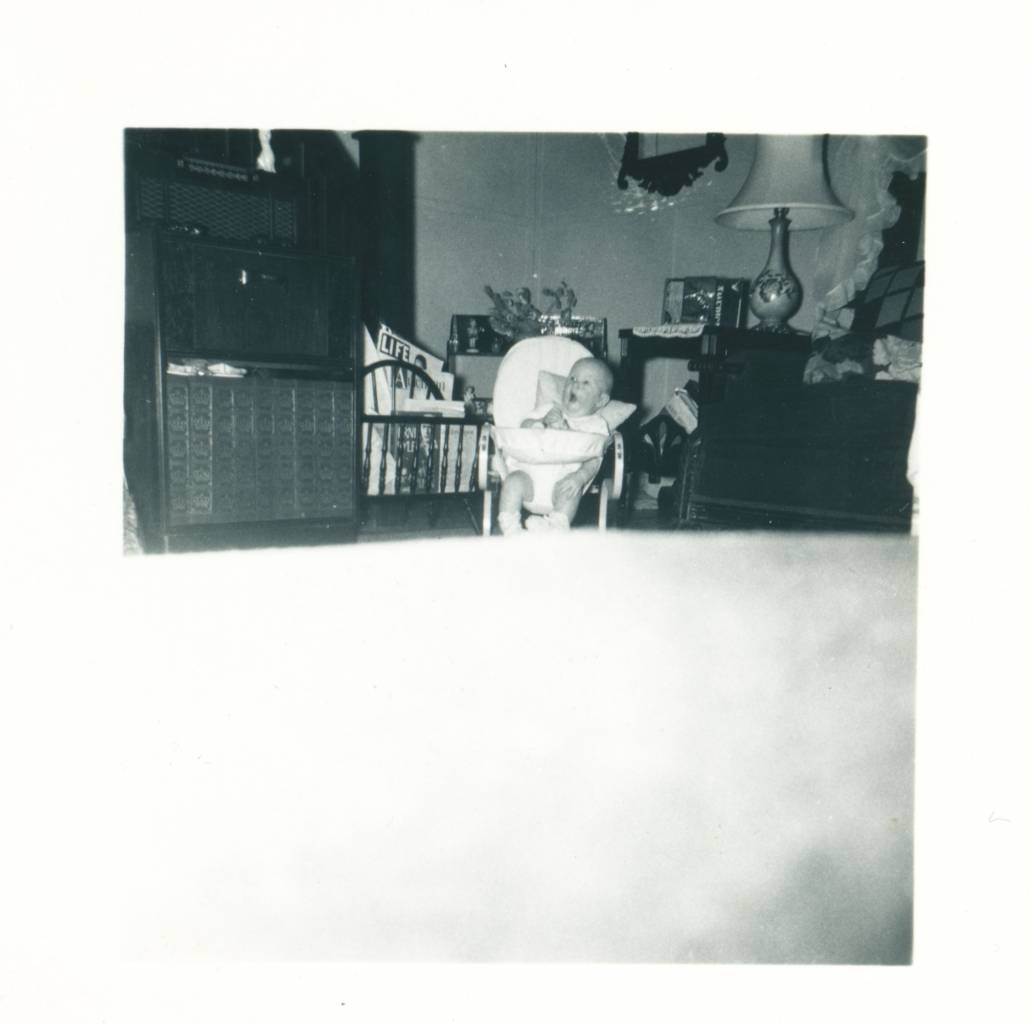

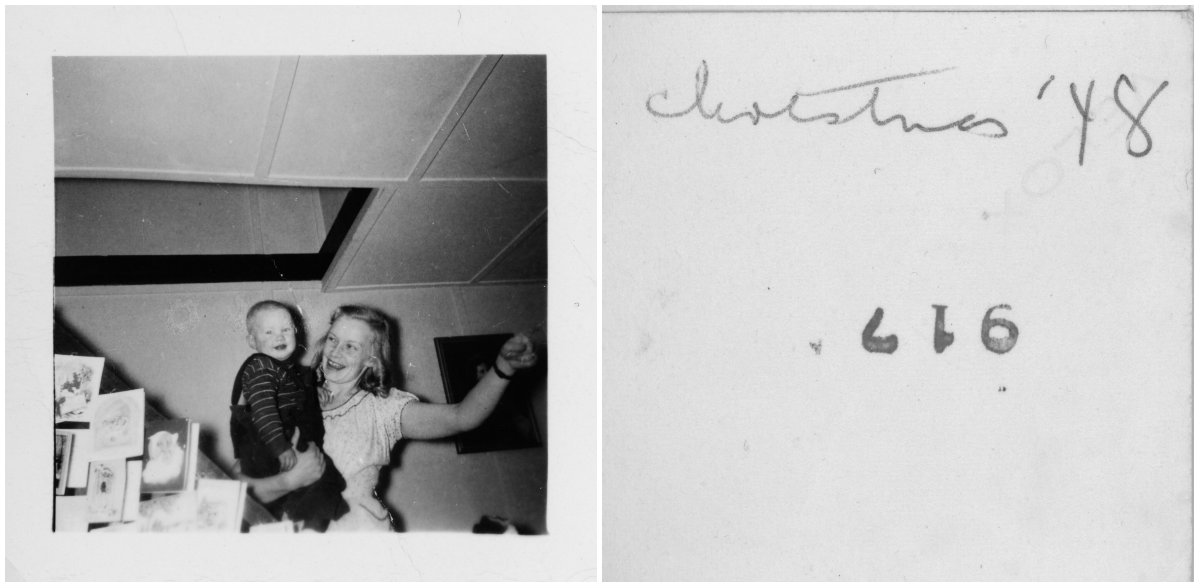

Early pic of me (Ted Polhemus) with my mother (‘Peggy’ (Margaret) Polhemus), 19 Oak Terrace, Neptune City, New Jersey, Christmas, 1948

The return of the GIs, the economic prosperity and the baby boom might have resulted in a town like Neptune City building upwards with multistory dwellings, replacing the often jerry-built or ramshackle bungalows; in the process finally realizing the urban vision of Neptune City’s founding fathers. But that would have gone against the grain of the national mood.

The late ‘40s/early ‘50s were the golden age of the Western, High Noon (1952) and Shane (1952) not only demonstrating notions of rugged individualism and self reliance, which surely clicked with the soldiers come back from foreign parts, but also projected these values against a backdrop of seemingly limitless space. By the late ‘40s that other American bible, The Sears Roebuck Catalog, for the first time included page after page of denim clad ‘cowboys’ and ‘cowgirls’ who proclaim ‘Yippee!’

The astounding success of the 1955 film of the musical Oklahoma! drove the point home: real Americans, heroic Americans needed land to roam free – if not the Great Plains or the Rockies, then at the very least your own backyard where you could, like cowboys, fire up the barbeque and cook some real American meat.

Back in 1947, on Oak Terrace, all this momentous transformation of America and of our lives as Americans was still to come, a fantasy just taking shape. My mother pushes me in my huge pram to the shops to buy dinner, over to my grandparents, perhaps to get rid of me for a few hours so she can go and have her blonde hair permed in the Veronica Lake style she favored at that time. Or we might go off to watch the boys playing baseball on the vacant lot. Years later with, I always thought, worryingly, just a touch too much twinkle in her eye, she would time and again tell the story of how one day a baseball hit high and wide landed just inches away from my pram. ‘Could have killed you’, she would add. Was the boy who hit the near deadly baseball the nine year old Jack Nicholson, who was growing up a few blocks over from Oak Terrace? Unlikely to be the three year old Danny DeVito whose family owned, or would go on to own, the dry cleaners and the pool hall.

Anyway, I survived the baseball and the, some might think, cramped and old-fashioned lifestyle of Neptune City.

Early pic of me (Ted Polhemus – bald head bottom right) with, from left to right, my mother’s father the Rev Joseph W Chasey, my father’s mother Nancy Allgor (sp?)-Polhemus, my mother (Peggy Chasey-Polhemus), my mother’s mother Carrie Chasey and, far right, my father’s father Russell Polhemus – I would guess taken at my mother’s parents’ home in Interlaken, New Jersey, USA

I’ve been told this a 1938 Plymouth with an extra, showy ‘over-rider’ bumper fitted (the same car Philip Marlowe drove in the 1946 film of The Big Sleep). I’m guessing that this must have been a new family car in 1948/9 photographed I think at 19 Oak Terrace, Neptune City, New Jersey, USA.

Within just a few years, all of us – Jack, Danny and I – and our families had left Neptune City. (Nicholson’s family being rather unconventional, in that his ‘mother’ was actually his grandmother, his ‘sister’ in fact his mother – all of which my father told me long before Jack apparently knew it himself.) As a result, that Small Town America which GIs like my father had fought to defend and then triumphantly returned to, went into decline – one from which it will probably never recover. (At least not until the oil really does run out and, no longer able to get the kids to school, their food from the supermarket, a future generation of Americans might conceivably rediscover the practical and social advantages of small town life.)

In the late ‘50s/early ‘60s I attended Neptune Junior High School, at the time located in the old Neptune High School building to which my father had gone, across the street from ‘the shack’ in which he and his brother Doug had grown up.

Twice a day my mother would run me the couple of miles to and from the school in her embarrassingly old and dilapidated car – we now, inevitably, having become a two-car family. This journey took us the length of Corlies Avenue which, with each passing year, became less of a town center where people went for a haircut, to the bank to top up their savings account, to pick up a couple of chops from the butcher, and became more and more a last refuge for those who had missed the boat on the American Dream. Failed or failing shops (some of them, no doubt, once a thriving part of Neptune City life, others just chancing what could be made of very low rents) littered the street – the stone fronted bank, now featuring a drive-in facility off to its still vacant side, looking ever more absurd and sad with each passing year.

Me (Ted Polhemus) with my father’s mother (Nancy Polhemus) and unknown woman on the right, at my father’s parents’ house at 1205 9th Ave, Neptune City, New Jersey, USA, Christmas, 1949.

From left to right: my mother’s mother, Carrie Brookes-Chasey, my mother’s sister’s boy Chuck, my mother’s sister, Ruth Tickner, me, my mother’s sister’s daughter Beverly, my mother’s mother’s sister Agnes Brookes (like so many women of her WWI generation, she never married)

The only members of my family who stayed on in Neptune City (Uncle Doug having married and, on the profits of his thriving gas station, moved to a particularly upmarket suburb) were my paternal grandfather Russell Sage Polhemus and his older sister Charlotte. One of my childhood heroes, a bit of a black sheep, rumoured occasionally to be found in The Green Parrot bar over by the hospital on Highway 33, strangely sophisticated and stylish for our family, Great Aunt Charlotte had by this time retired from her job as a fashion buyer for the prestigious Steinbeck Department Store in the still grand city of Asbury Park. A victim of that other great post-war demographic blip, the shortage of marriageable young men after WWI, Aunt Charlotte had never married and now, perhaps due to reduced circumstances, maybe from a sense of family responsibility, possibly just seeking companionship, lived in one of the two small bedrooms in Grandpop Polhemus’ bungalow on 9th Avenue in Neptune City.

Grandpop’s wife Nancy Allgor Polhemus, my father’s mother, a country farm girl famous in her youth for walking some ten miles to church and back every Sunday, died in the early ‘50s only a few years after seeing both her sons leave home for the newfangled suburbs. At the funeral, tears streaming down his face, Grandpop exclaimed to my father, ‘Charles, it’s a terrible thing. First my dog dies and now my wife’. When his sister Aunt Charlotte died in the late ‘50s (my getting the bed she died in causing many a nightmare) Grandpop carried on alone in his bungalow.

A man who believed that the secret of a long life (and it must be admitted he lived into his 90s, surviving both his children as well as his wife) was to expose oneself to fresh air as little as possible, Grandpop Polhemus ventured from his bungalow only on Tuesday and Thursday evenings when he would have a meal with, in turns, our family and then Uncle Doug’s.

Me (Ted Polhemus) with my mother’s sister’s son Chuck Tickner. This was probably in Union Center, NY, USA

After I got my driving license in 1964 until the time I went off to college, I would go to collect him. Given that the windows and doors were rarely if ever opened, and given that Grandpop’s life was measured out in Montecristo (but not real Cuban) cigars, I would hope to get in and out as quickly as possible. Outside on the porch, each and every time, he would hand me a dollar (not, in fact, sufficient for this purchase even then) and suggest I go over the street to what had once been my father’s corner store and get some ice-cream. ‘What flavor?’ I would ask, knowing full well the answer. ‘Cherry vanilla, Briars Cherry Vanilla’ would be his suggestion, ‘everyone likes that’, when, in truth, no one in either family except Grandpop much cared for cherry vanilla – thereby ensuring that the old guy would consume close onto a gallon of the stuff every week.

At dinner, if you passed Grandpop a serving plate of, say, peas, he would want to know if they were Birdseye because ‘they freeze them straight from the field’, or whatever was the tag line of the current TV commercial. This was because, as disinclined to sleep in his bed as to take a bath, Grandpop would spend his nights resting in his Lazy Boy recliner and watching three old TV sets at once, all on the same channel, his great and terrible abiding fear being that two sets might cease to function simultaneously – a fear which was not all that unrealistic back in the early days of TV but which, now in the ‘60s reliability having improved, was arguably a little over the top. Breakfast, his only sustenance apart from Tuesday and Thursday nights eating out, was always Nabisco Shredded Wheat – full boxes stacked against one wall, empty boxes stacked on the wall opposite, a little table, a chair, a bottle of milk, a bowl and a spoon in between.

It was a similar story on the dinning room table: unopened boxes of Montecristo cigars (gifts for his birthday, Father’s Day or Christmas – it was never a problem knowing what to get him) at the far end, a small pile of the twist string openers from the cigars, a mountain of the cellophane cigar wrappers and, finally, a carefully arranged stack of the empty boxes. A sensible, orderly (but not,it must be said, very clean) man, Grandpop thought it a waste of time taking down and then putting up again his Christmas decorations. So, even in July, the stuffy, hot, airless bungalow was festooned with strings of old Christmas cards – layered up and up in a sort of archaeological stratification – and, if my father had not insisted upon taking it away, last year’s long deceased Christmas tree.

Such was Grandpop Polhemus’ life in Neptune City, after the rest of the family had died or moved away to the suburbs.

Near the end of Philip Roth’s Sabbath’s Theater, on a whim, Sabbath visits his hundred year old Uncle Fish, who is also living a lonely and less than spic and span existence about a mile away from Grandpop’s bungalow, in Bradley Beach. Fish’s place is two stories high, and although he does not really sleep much he does go up to bed at night. He tells Sabbath he’s out of cereal (an eventuality which, due to careful stockpiling, would never befall Grandpop) but does make his own lunch every day: a lamp chop, a little apple sauce with maybe an orange for dessert. Of course there are no Christmas decorations, Fish being Jewish. Also, unlike Grandpop Polhemus, Fish would have a shower occasionally. In an old sideboard which used to belong to his family (his parents both now dead), Sabbath finds a box marked ‘Morty’s Things’.

Unlike Sabbath and my father and uncle, Sabbath’s younger brother Morty didn’t survive the war – shot down over the Pacific. At the bottom of the cardboard box Sabbath finds the officially folded flag which had draped his brother’s coffin. For some of us the obvious yet all too easily forgotten truth is that a great many GIs never made it back to their home towns and many of those who did, unlike my father and my uncle, were deeply scarred psychologically if not physically. Such GIs had had their High Noon showdown and most of them, like Gary Cooper’s Marshal Will Kane, had lived up to the terrible challenges of their time, their war. They had done what a man’s got to do. Now that war was over and for the survivors it was time to move on to a new – and who could possibly doubt it? – better life for themselves and their growing families. Now was the future, an American, suburban future.

All images and text copyright Ted Polhemus. You can read the story behind the pictures and what happened next in Ted’s book BOOM! – A Baby Boomer Memoir, 1947-2022.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.