In 1870, Danish carpenter Jacob Riis, 21, took his berth in steerage on the Iowa and journeyed from Glasgow to New York. Riis disembarked in New York on June 5. In his pockets he carried his worldly goods: a lock of his lover’s hair (while he was away she married a military hero in Denmark) and $40 his friends had given him. He soon invested half the cash on a revolver for defense “against human or animal predators”. He might have bought some bullets.

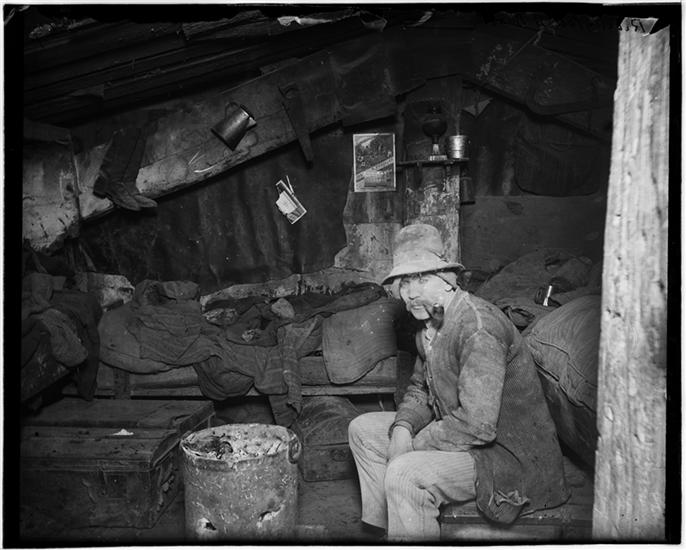

One night Riis was bedding down in the Church Street Station Lodging-room when his gold locket keepsake was stolen and his dog clubbed to death. That night, he recalled, cured him of dreaming. In squalor “all the influences make for evil,” he wrote.

His social conscience pricked and bloodied, Riss found work as a journalist covering the impoverished Lower East Side. He soon began lecturing on the state of the city’s poor. The title of his talks was morbid: “How the Other Half Lives and Dies.” It was abridged for his 1890 book How the Other Half Lives.

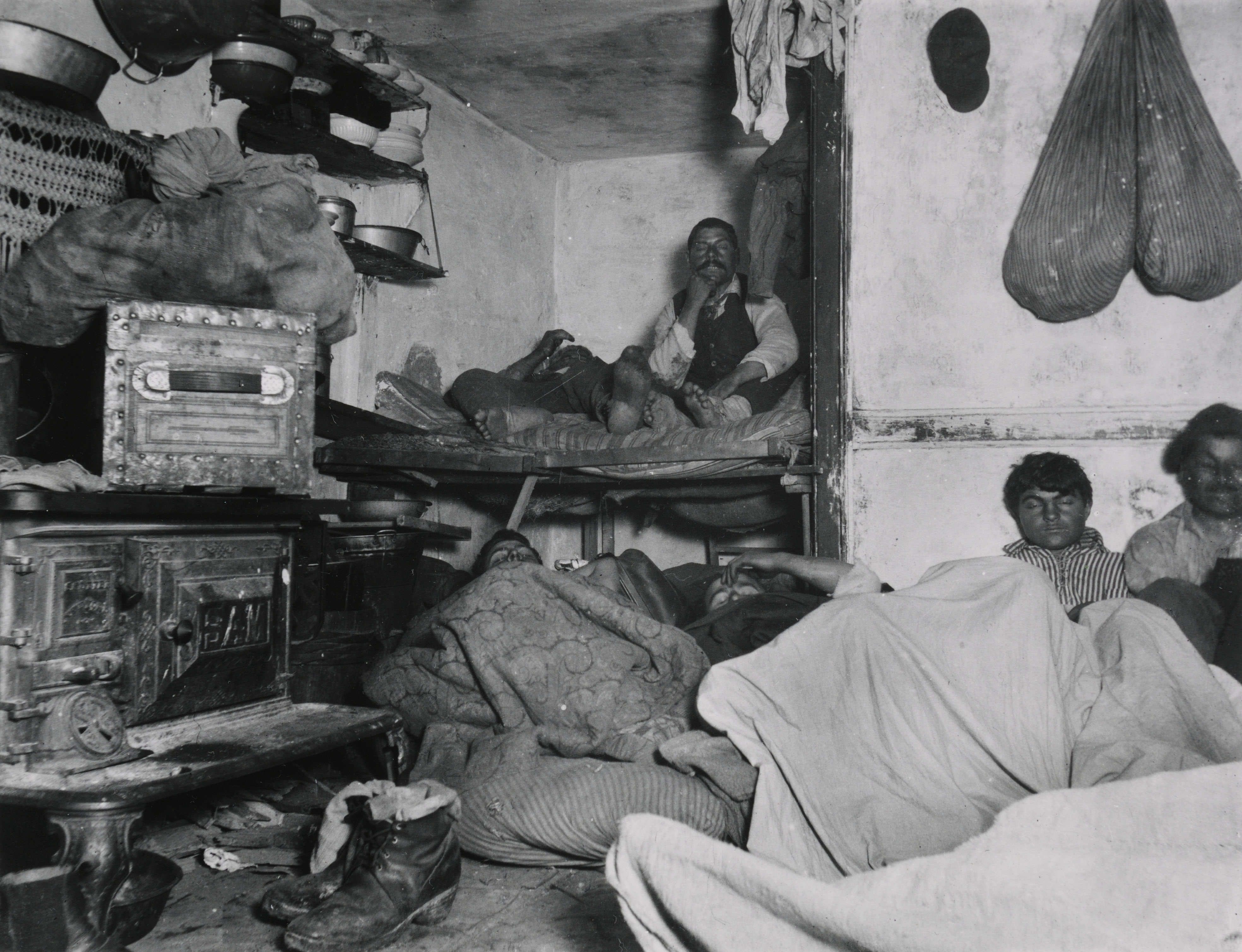

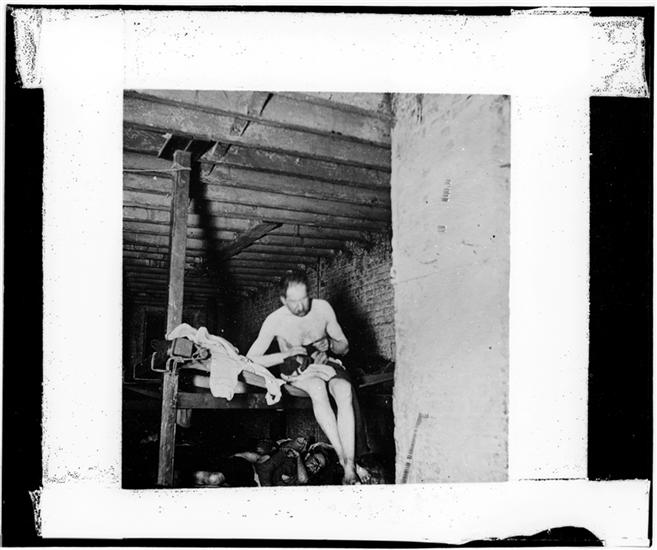

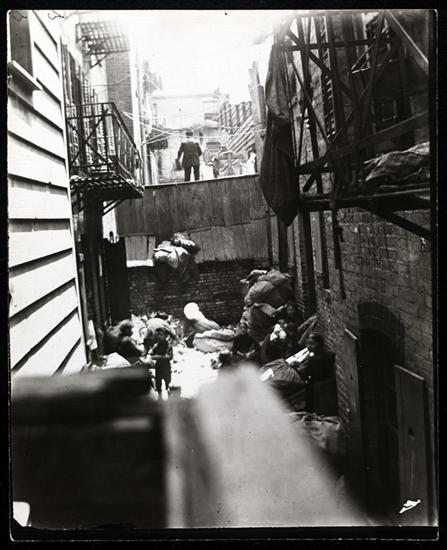

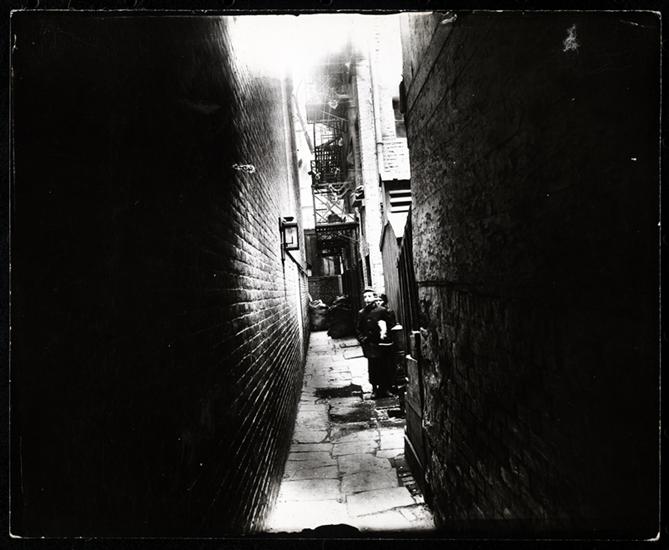

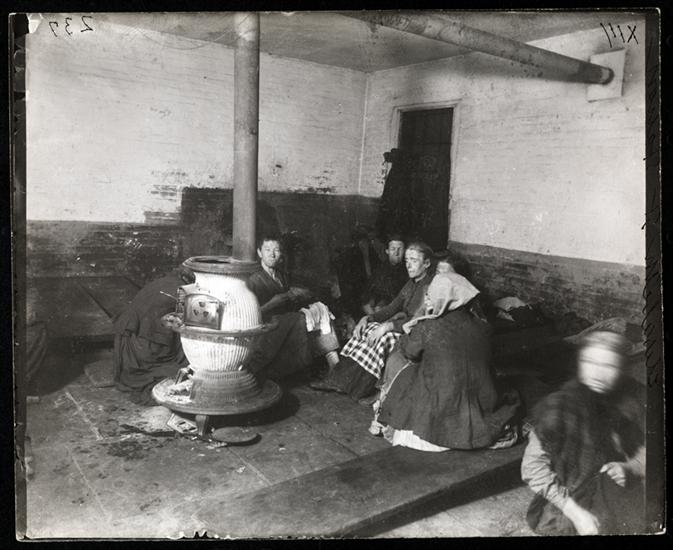

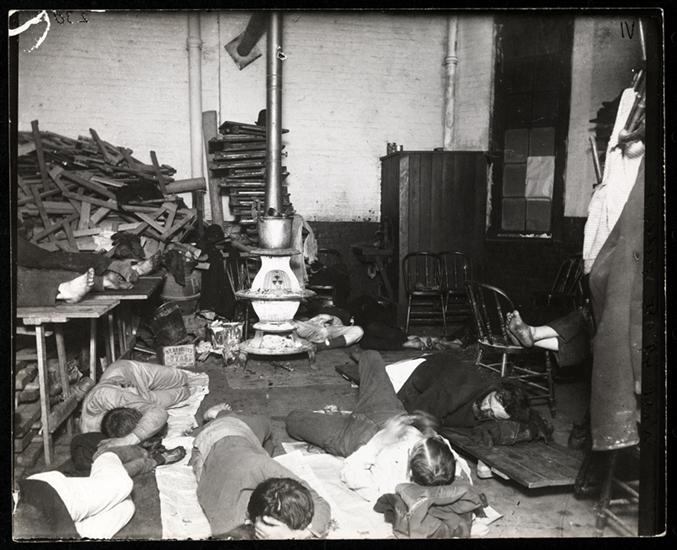

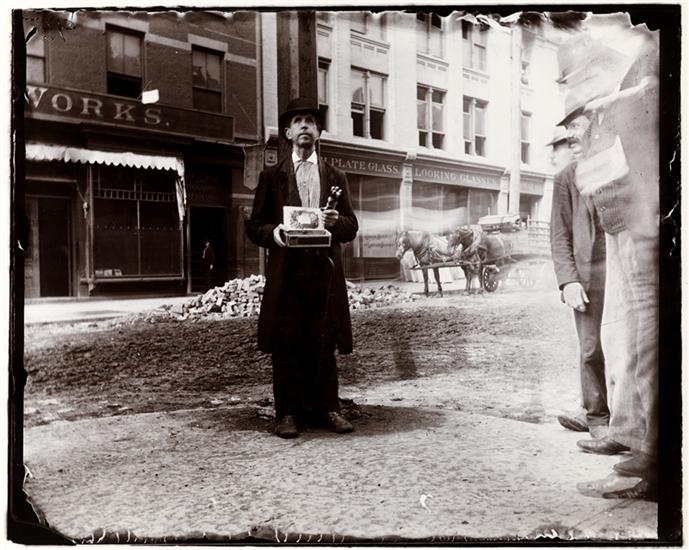

He realised photography possessed the power to capture a moment and transmit it to the nation. Leading a team of amateur photographers equipped with magnesium powder and potassium chlorate to produce Blitzlicht, and a tooled-up policeman, Riis fired a flashbulb into the dingy, airless rooms in rear tenements where natural light never ventured – where people would rent a “spot” on the floor for 5 cents a night – sweatshops and alleyways where people for whom New York’s Gilded Age was elsewhere existed and perished.

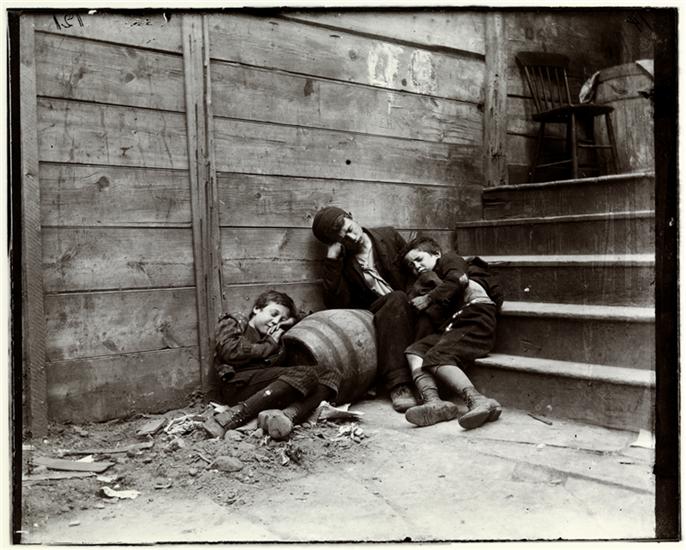

Some of his images seem staged. In one picture of urchins, or “street Arabs” as Riis called them, you can see the smile on a boy’s face as he’s told to lie still and wait for the flashlight to explode.

Photographs often need a narrative to make a point. Riiis’ writing, as he noted, “did not make much of an impression — these things rarely do, put in mere words — until my negatives, still dripping from the dark-room, came to reinforce them.” “I am a writer and a newspaper man,” said Riis. The story was all.

Riis’ campaigning style and work as police reporter for The New York Tribune brought him to the attention of police commissioner Theodore Roosevelt, who said of his friend: “The countless evils which lurk in the dark corners of our civic institutions, which stalk abroad in the slums, and have their permanent abode in the crowded tenement houses, have met in Mr. Riis the most formidable opponent every encountered by them in New York City.”

The belief that every man’s experience ought to be worth something to the community from which he drew it, no matter what that experience may be, so long as it was gleaned along the line of some decent, honest work, made me begin this book.

-Jacob Riis, Preface to How The Other Half Lives

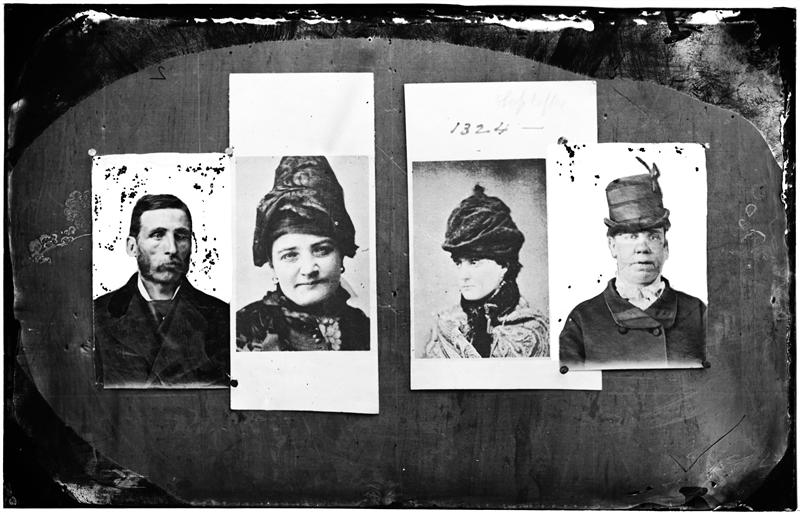

Rogue’s Gallery, Funeral Wells & Sofy Levy; and 2 other women thieves — the prettiest & the ugliest in the Rogue’s Gallery put together. The Pretty one is a blackmailer; the ugly one a horse thief.

DATE:ca. 1890

Mug shots depicted differ from title description. Based on descriptive information in Thomas Byrnes’s “Professional Criminals of America” (1886 and 1895), the image purported to be of James “Funeral” Wells does not look like him. According to Byrnes, Sofy Levy’s real name was Sophie Lyons.

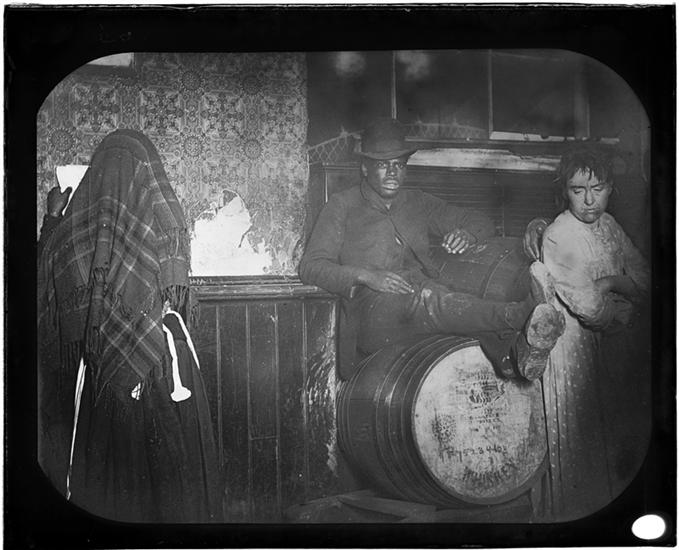

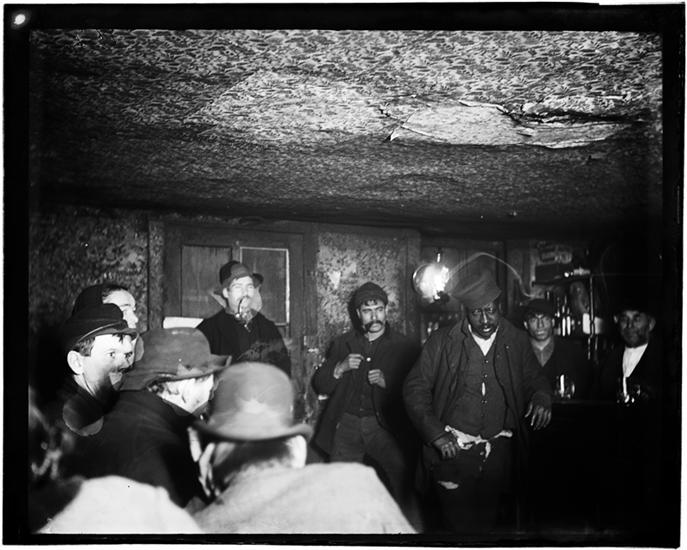

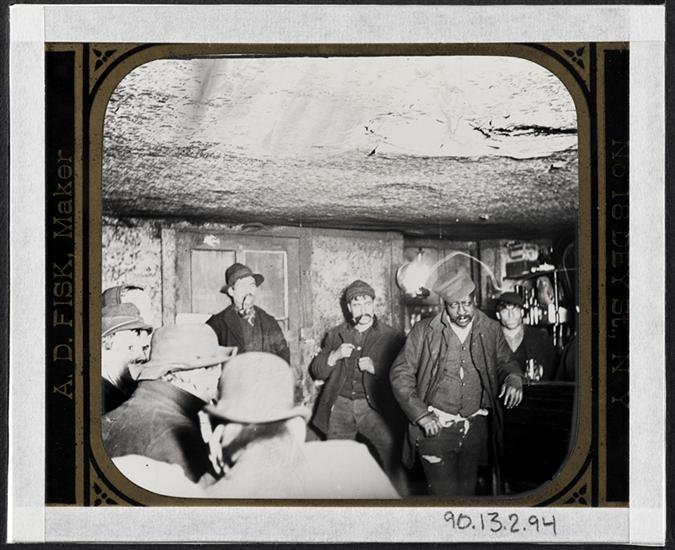

A Black-and-Tan Dive in “Africa.”

DATE:ca. 1890

An African American man seated on a whiskey keg flanked by two women in a “Black and Tan” dive bar on Broome Street near Wooster Street.

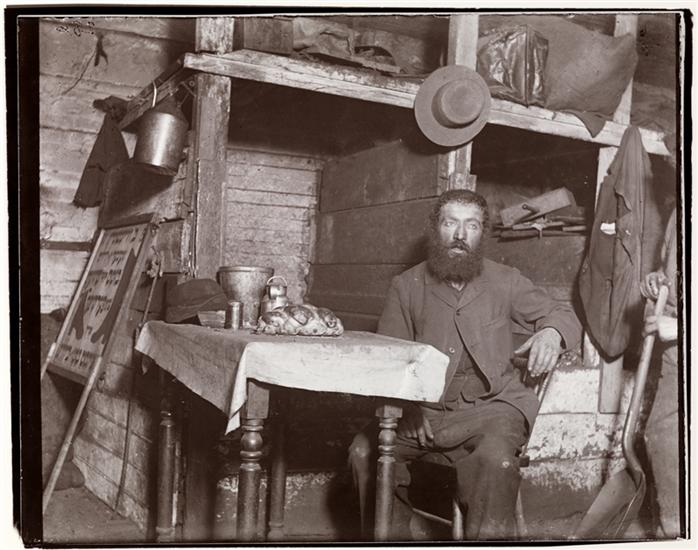

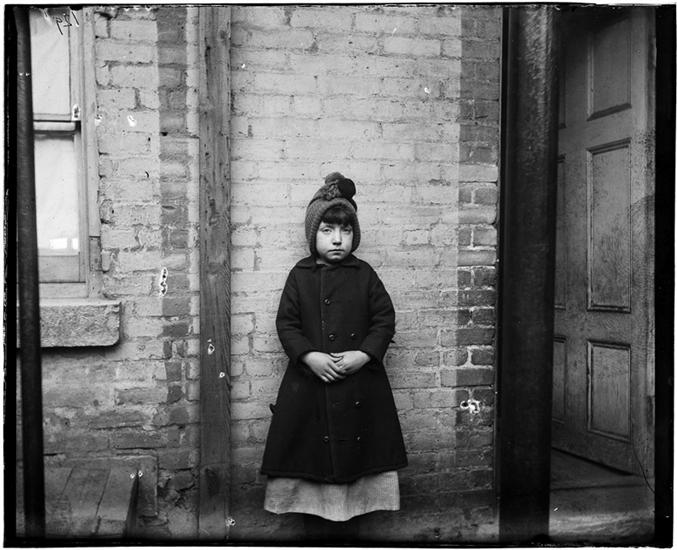

As was then, so it now: the immigrant poor are monstered and ignored. Slum dwelling are for slum people. So they say. The NY Public Library tells us:

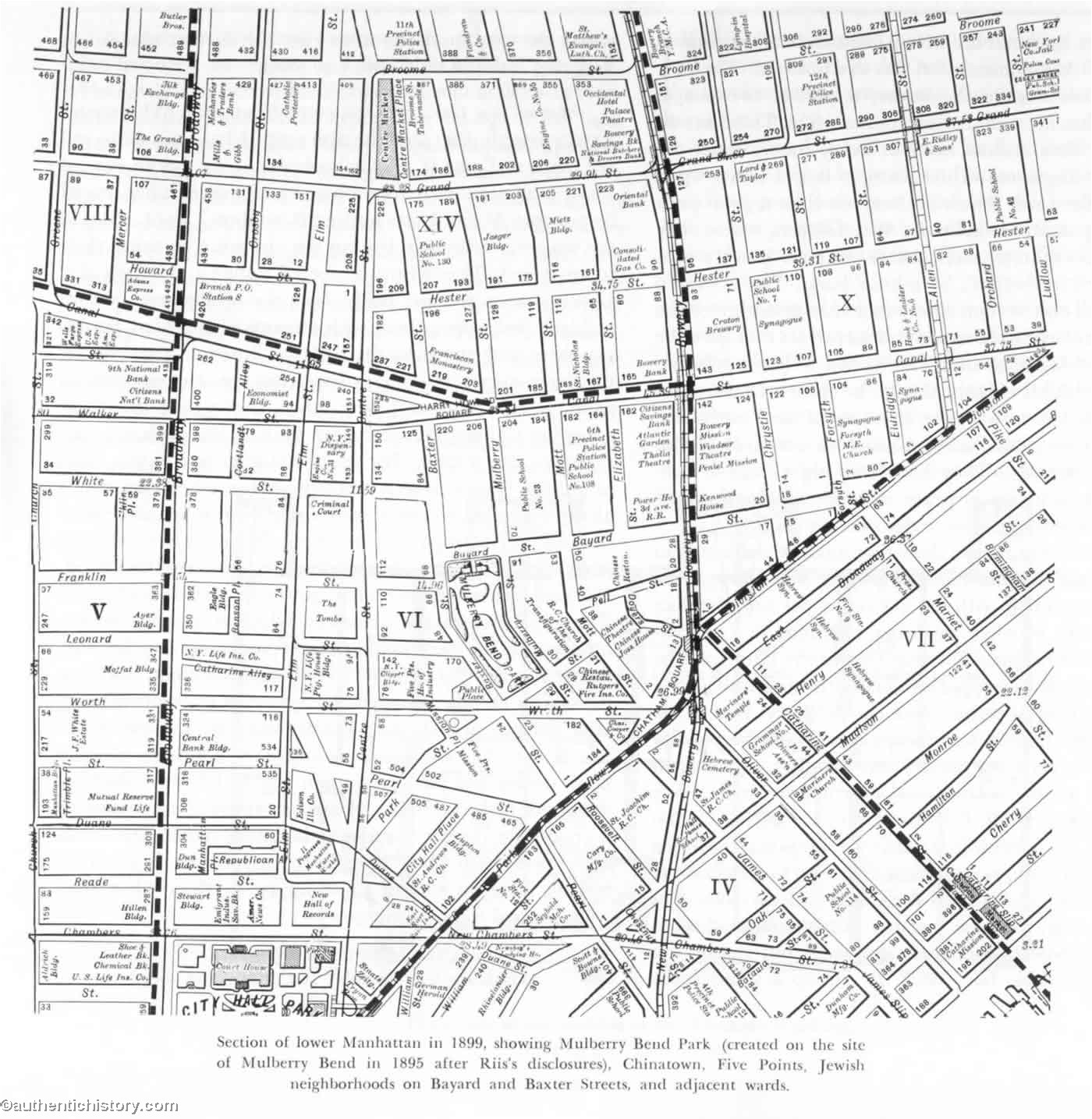

During the late 19th and early 20th centuries the population of Manhattan’s Lower East Side soared as tens of thousands of eastern European Jewish and Italian immigrants moved into the area’s crowded tenement buildings. These new immigrants found work in the garment industry, as pushcart vendors in the lively retail trade along Orchard and Grand Streets, and other trades. They established benevolent societies and fraternal organizations, joined local churches and synagogues, and participated in the thriving popular culture of the theaters and dance halls on 2nd Avenue and The Bowery. But flourishing alongside this working class culture were a host of urban problems. Poverty, hunger, disease, crime, decrepit housing and unsanitary streets were all pervasive on the Lower East Side. Such conditions dimmed the hopes of many immigrants. They also alarmed many wealthy and middle-class Americans who perceived in them threats to moral order, political stability and cultural progress. Early attempts to ameliorate conditions in a changing urban society included the creation of charity organizations, industrial training schools, and church missions.

LONG ago it was said that “one half of the world does not know how the other half lives.” That was true then. It did not know because it did not care. The half that was on top cared little for the struggles, and less for the fate of those who were underneath, so long as it was able to hold them there and keep its own seat. There came a time when the discomfort and crowding below were so great, and the consequent upheavals so violent, that it was no longer an easy thing to do, and then the upper half fell to inquiring what was the matter. Information on the subject has been accumulating rapidly since, and the whole world has had its hands full answering for its old ignorance.

– Jacob Riis, Introduction to How The Other Half Lives

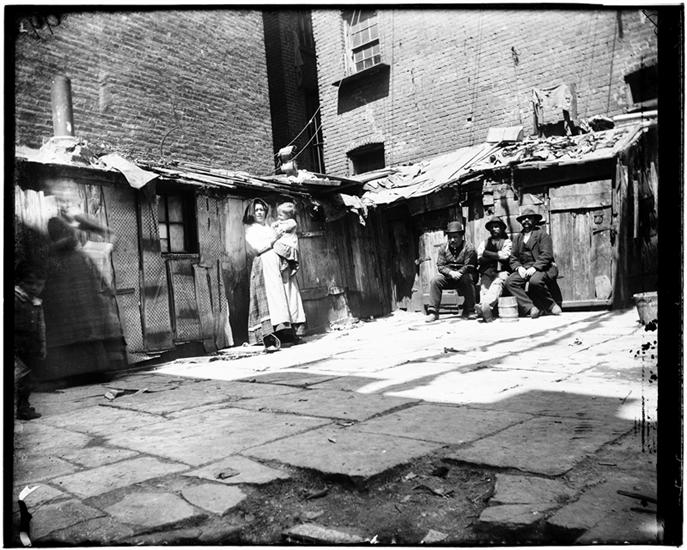

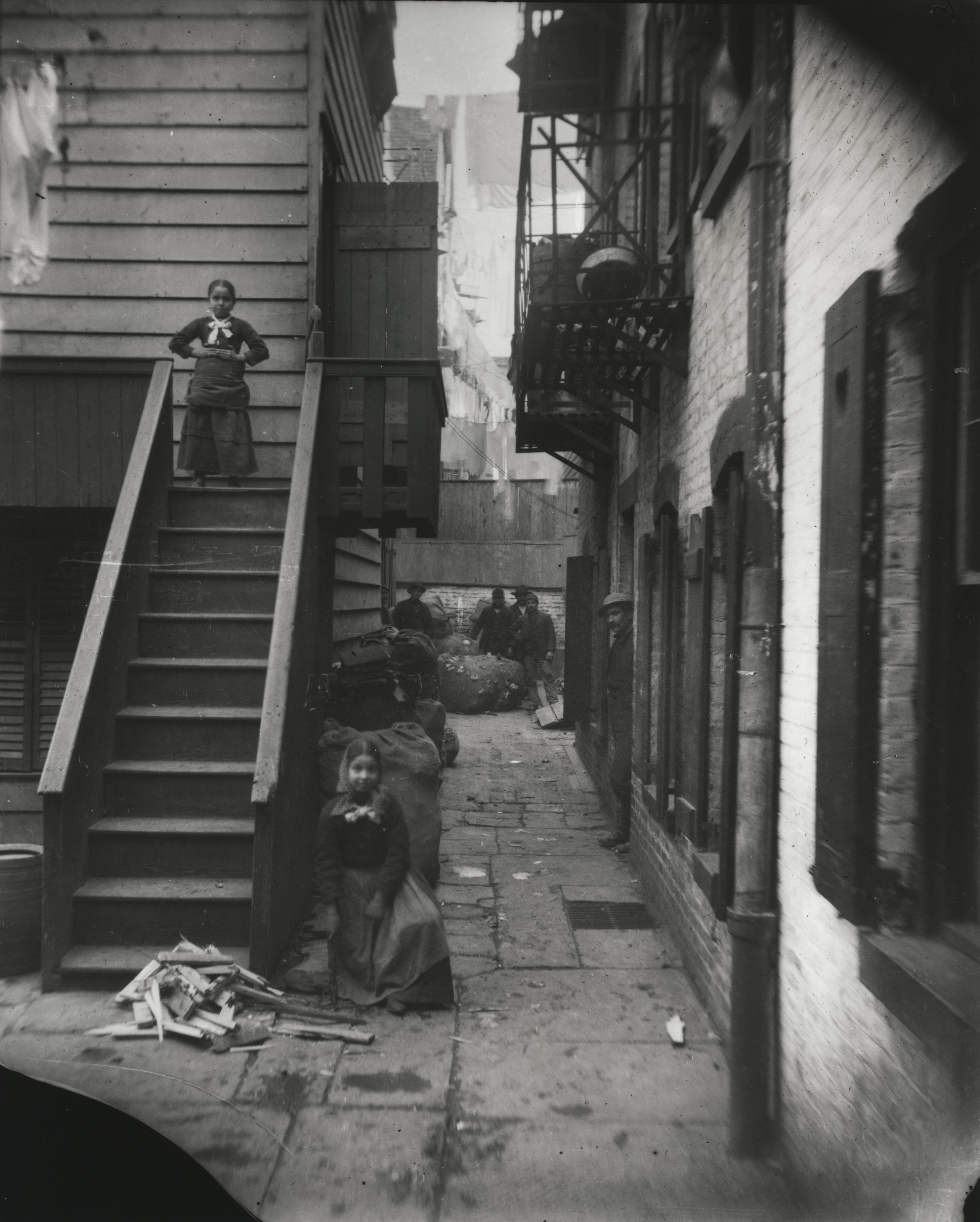

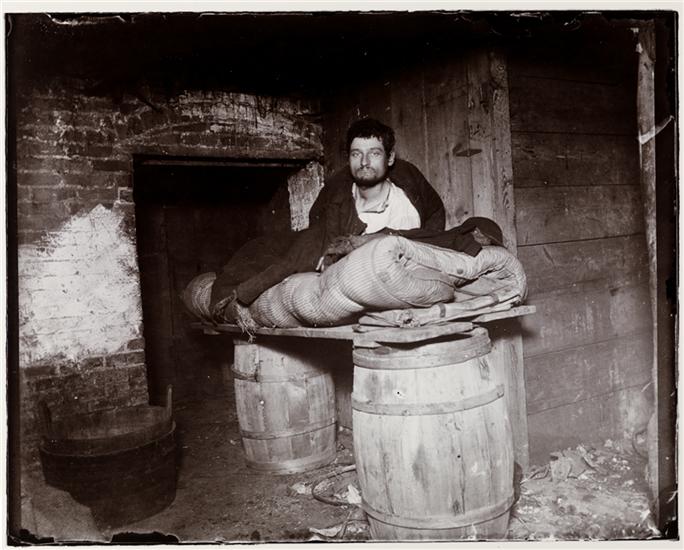

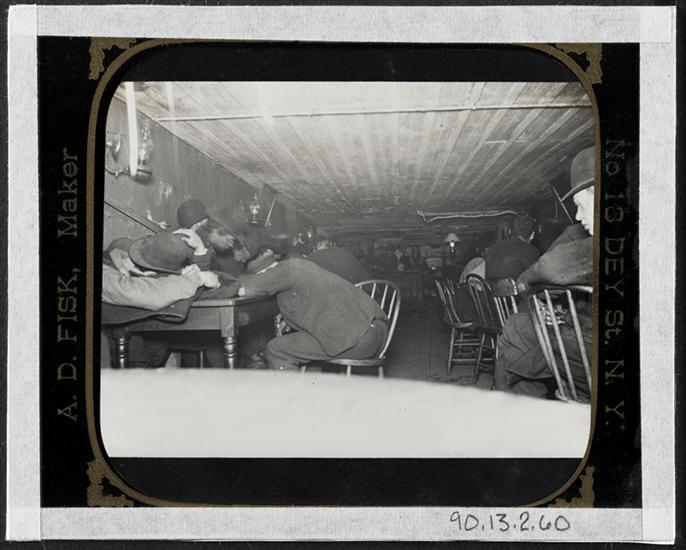

It costs a Dallar a Month to sleep in the Sheds.

DATE:ca. 1897

A woman holding a child, and men sitting in a rear yard of a Jersey Street tenement.

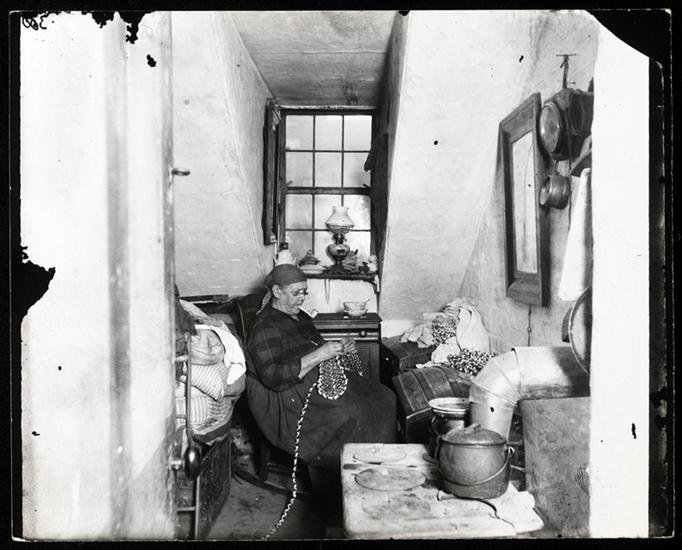

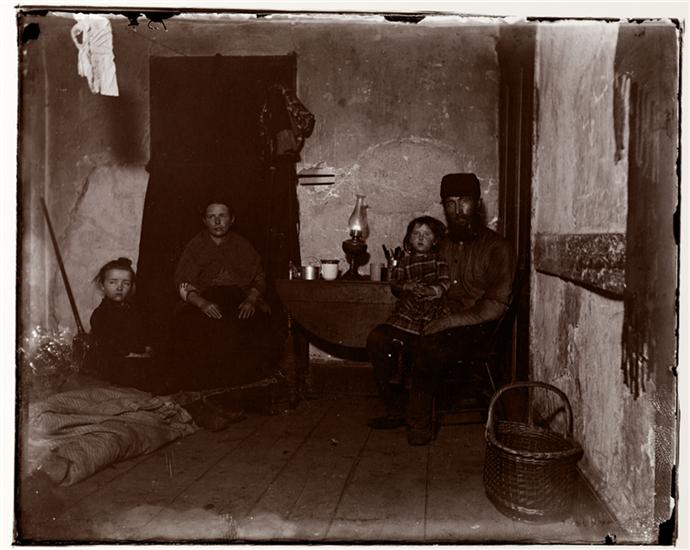

Old Mrs. Benoit in her Hudson Street attic, an Indian widow who lived there four years.

DATE:ca. 1897

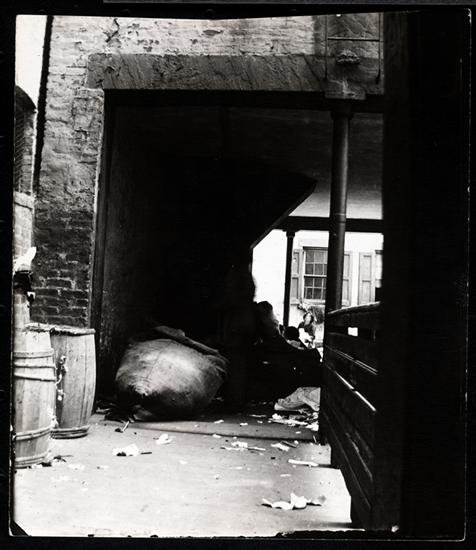

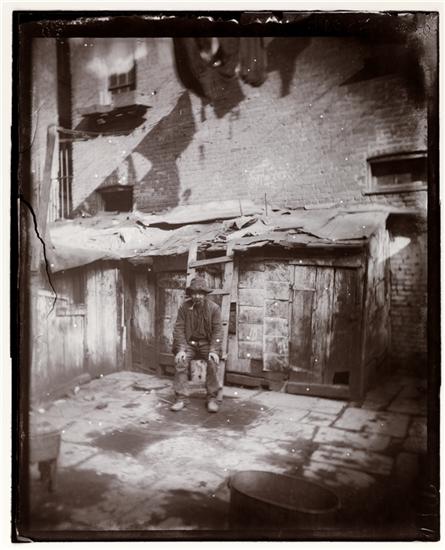

Arch under the first rear tenement at 55 Baxter Street leading to the second rear, with stairs up which Vincenzo Nino went to murder his wife in 1895. House believed to be haunted.

DATE:ca. 1890

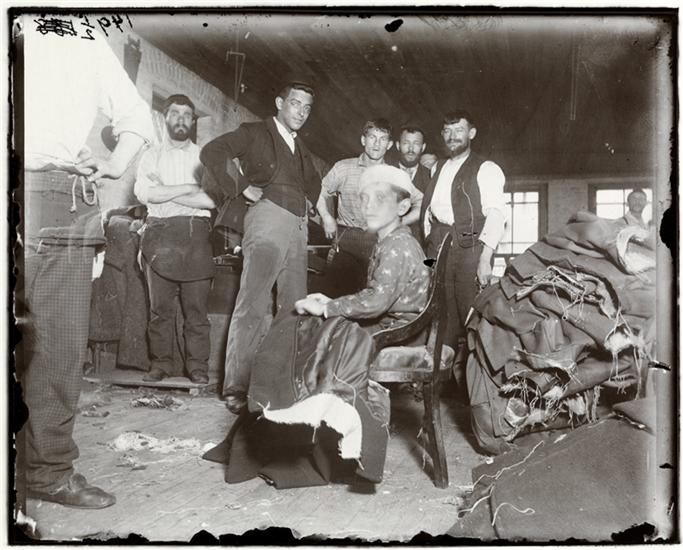

In a Sweat Shop.

DATE:ca. 1890

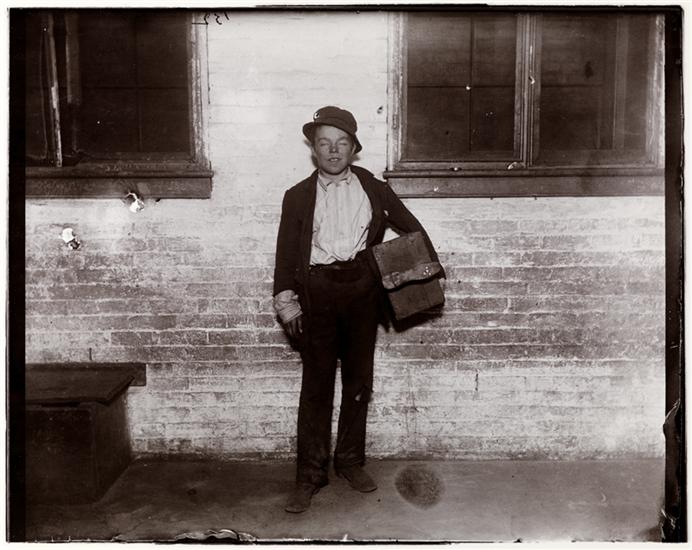

“12 year old boy at work pulling threads. Had sworn certificate he was 16 — owned under cross-examination to being 12. His teeth corresponded with that age.”

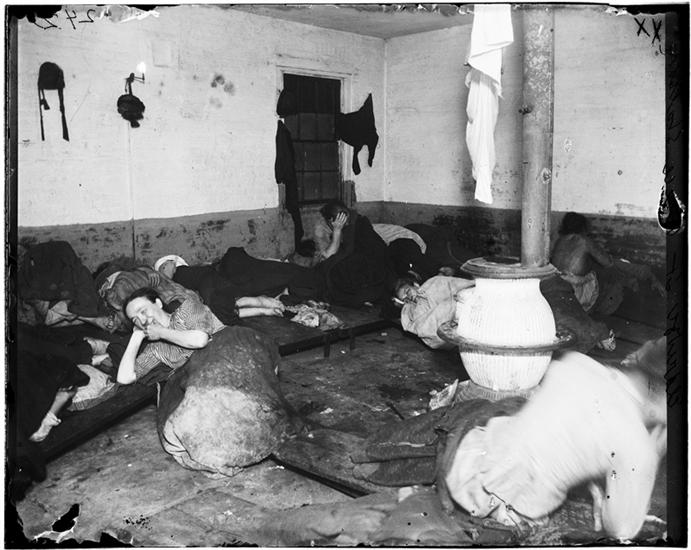

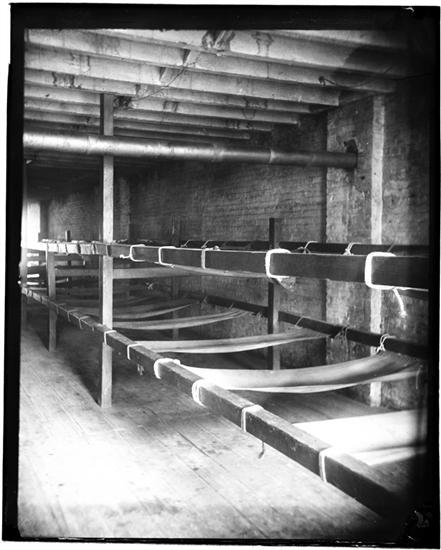

Women’s Lodging Room in Eldridge Street Police Station.

DATE:ca. 1890

Women sleeping on plank beds and the floor.

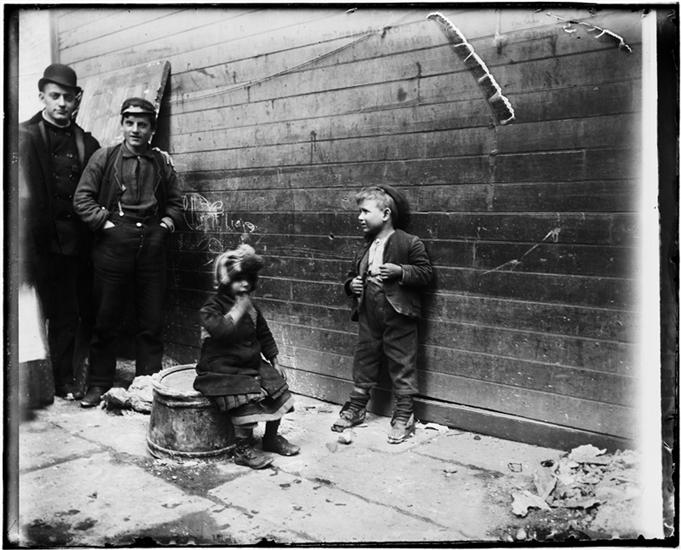

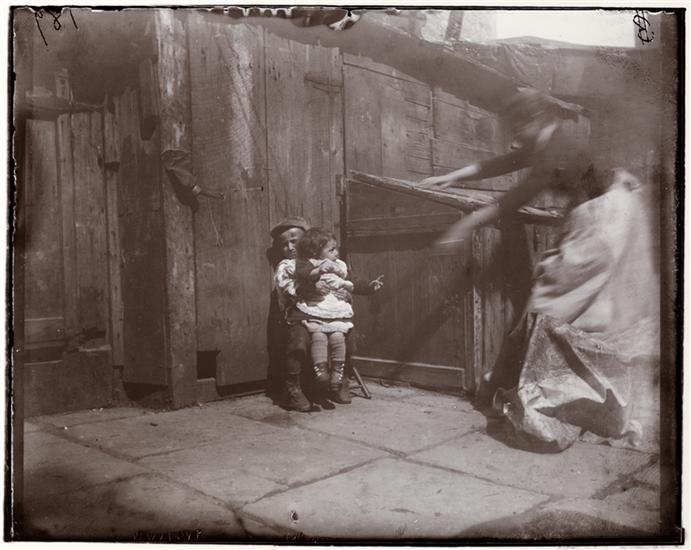

Two Greek children in Gotham Court debating if Santa Claus will get to their alley or not. He did.

DATE:ca. 1890

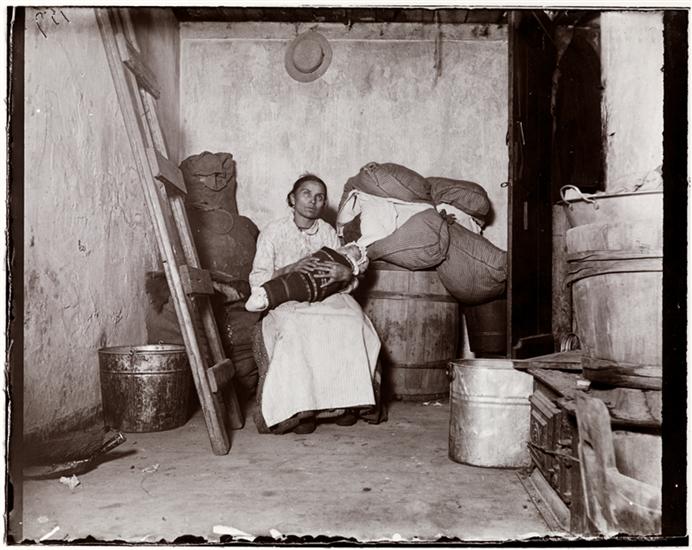

A “Scrub” and her Bed — the Plank.

DATE:ca. 1890

An old woman with the plank she sleeps on at the Eldridge Street Station women’s lodging room.

![Children in "The Ship," destroyed by B. of Health in 1897, after the visit of Roosevelt & myself [Jacob A. Riis] there. DATE:1895 Four children at a table, eating, in a tenement building known as "The Ship" on Hamilton Street.](https://flashbak.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/MNY201086.jpg)

Children in “The Ship,” destroyed by B. of Health in 1897, after the visit of Roosevelt & myself [Jacob A. Riis] there.

Four children at a table, eating, in a tenement building known as “The Ship” on Hamilton Street.

![The Old Gribbon sisters at 5 Van Dam Street photographed Dec. 1895 after I [Jacob A. Riis] had got them pensioned by Miss Emily Vanderbilt Sloane. DATE:1895](https://flashbak.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/MNY201081.jpg)

The Old Gribbon sisters at 5 Van Dam Street photographed Dec. 1895 after I [Jacob A. Riis] had got them pensioned by Miss Emily Vanderbilt Sloane.

When on May 25, 1914, Riis died of heart disease at age 65, Lillian Wald, founder of the Henry Street Settlement,

eulogized him “for friendship and encouragement and spirited fellowship, for opening up the hearts of a people to emotion, and for the knowledge upon which to guide that emotion into constructive channels.

Jacob August Riis (May 3, 1849 – May 26, 1914). Captions in italics by Riis.

Photos via: Museum of New York

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.

![The Church Street Station Lodging-room, in which I [Jacob A. Riis] was robbed. DATE:ca. 1890](https://flashbak.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/MNY12539-1.jpg)

![[Chinese Opium Joint.] DATE:ca. 1895](https://flashbak.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/MNY24761.jpg)

![[Bringing foundling to police.] DATE:ca. 1895](https://flashbak.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/MNY31619.jpg)

![New York "The Battle with the Slum" poster for Riis lecture.] DATE:1905](https://flashbak.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/MNY31489.jpg)