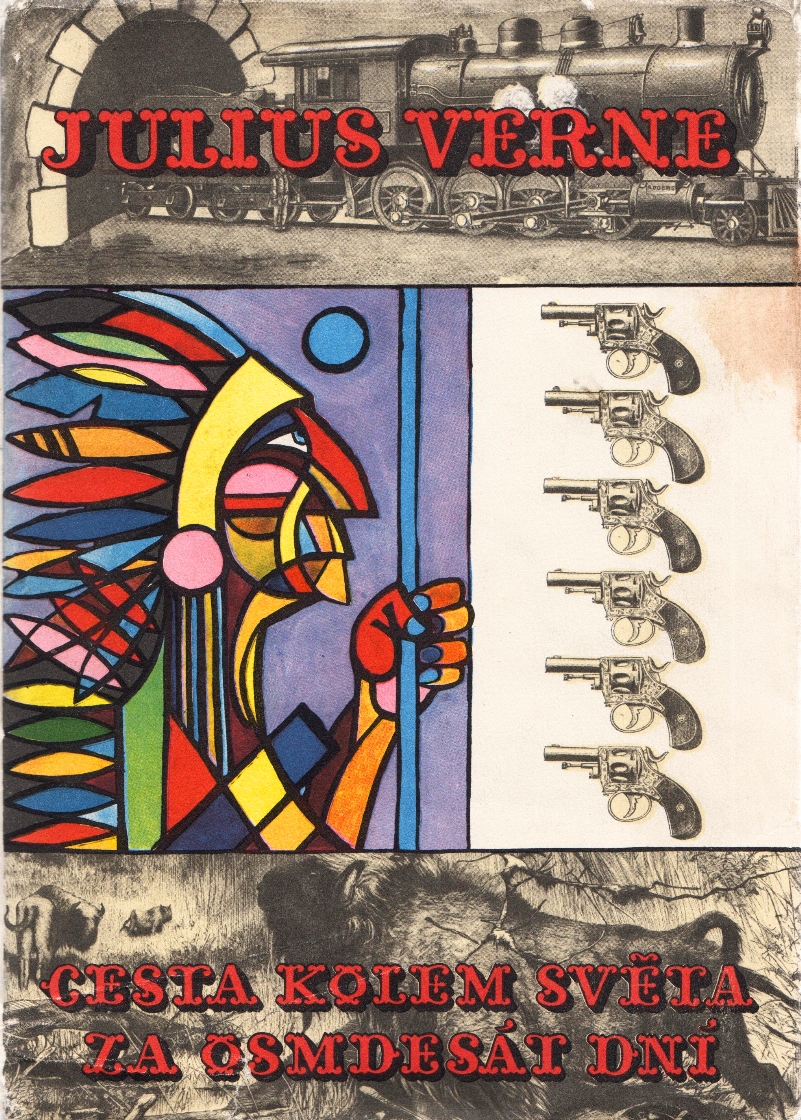

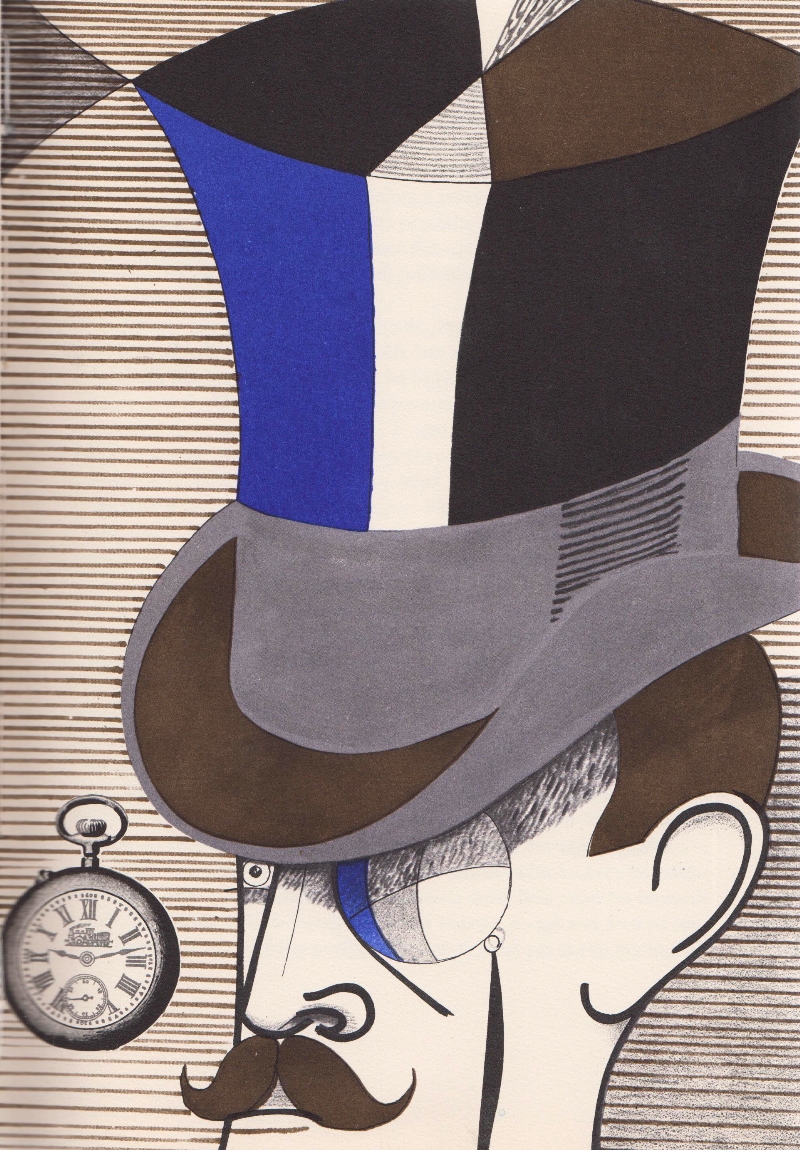

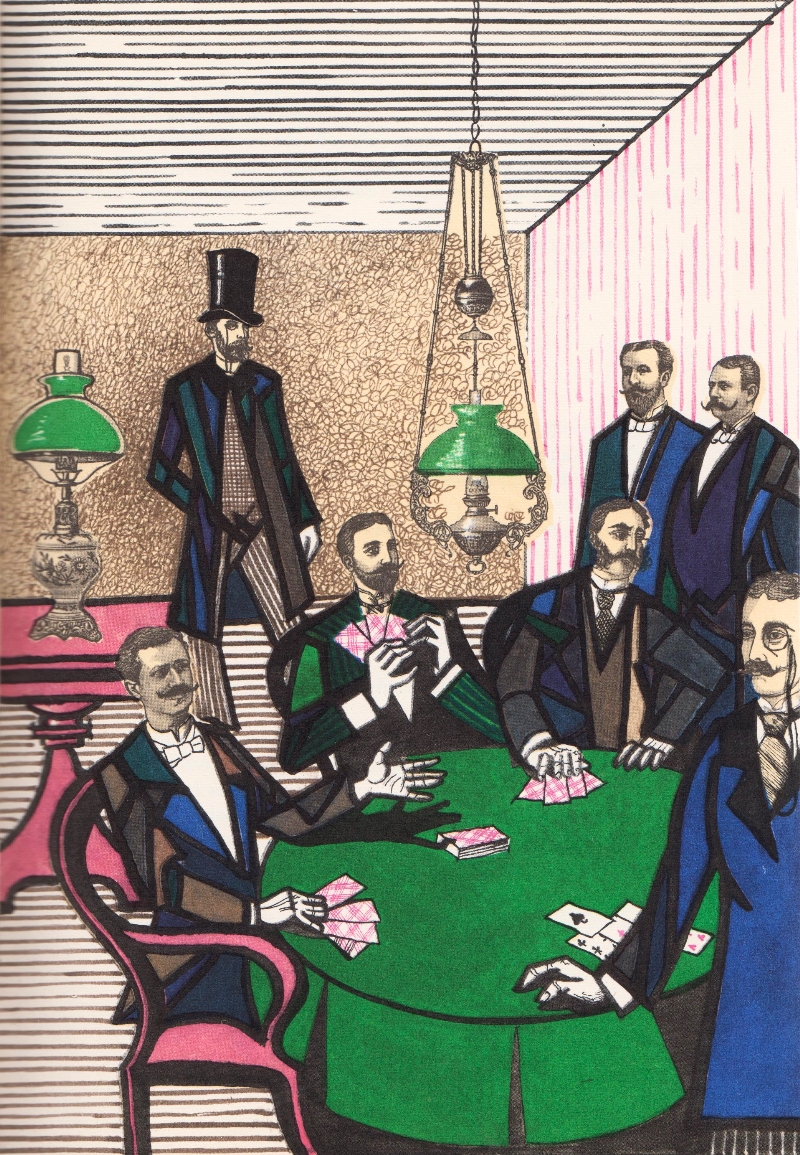

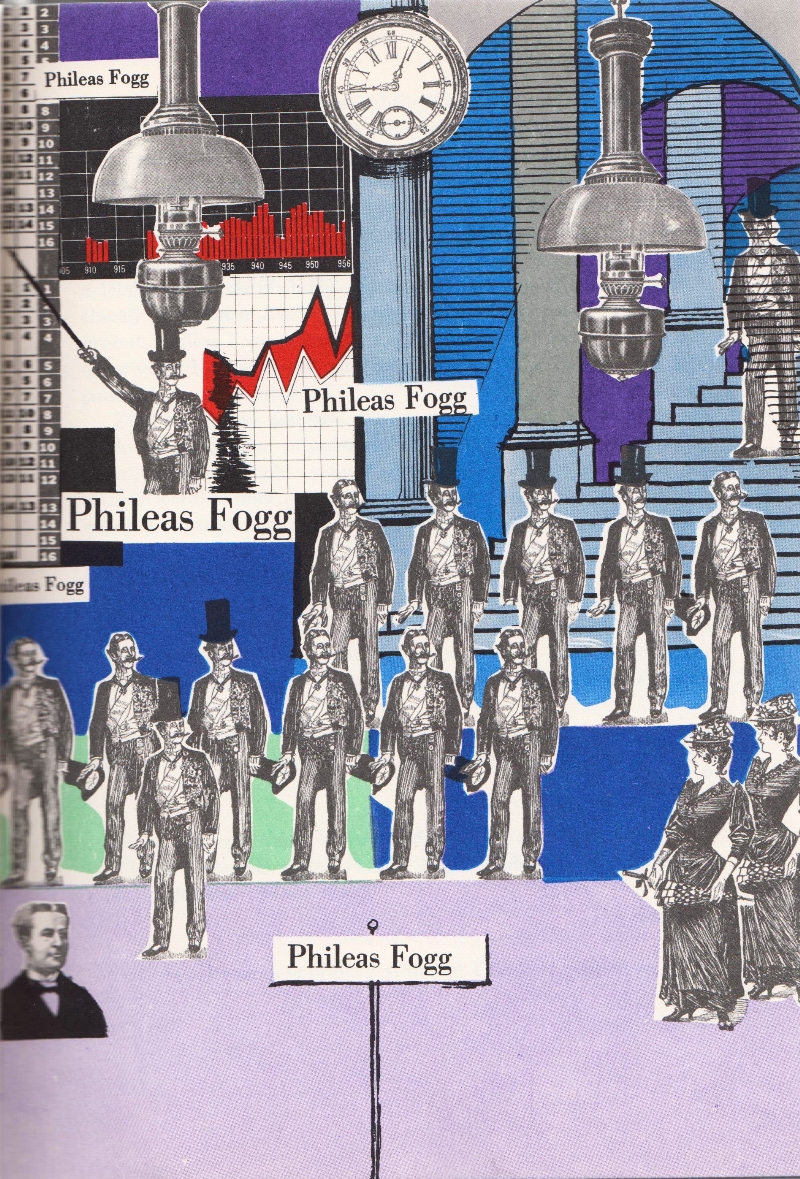

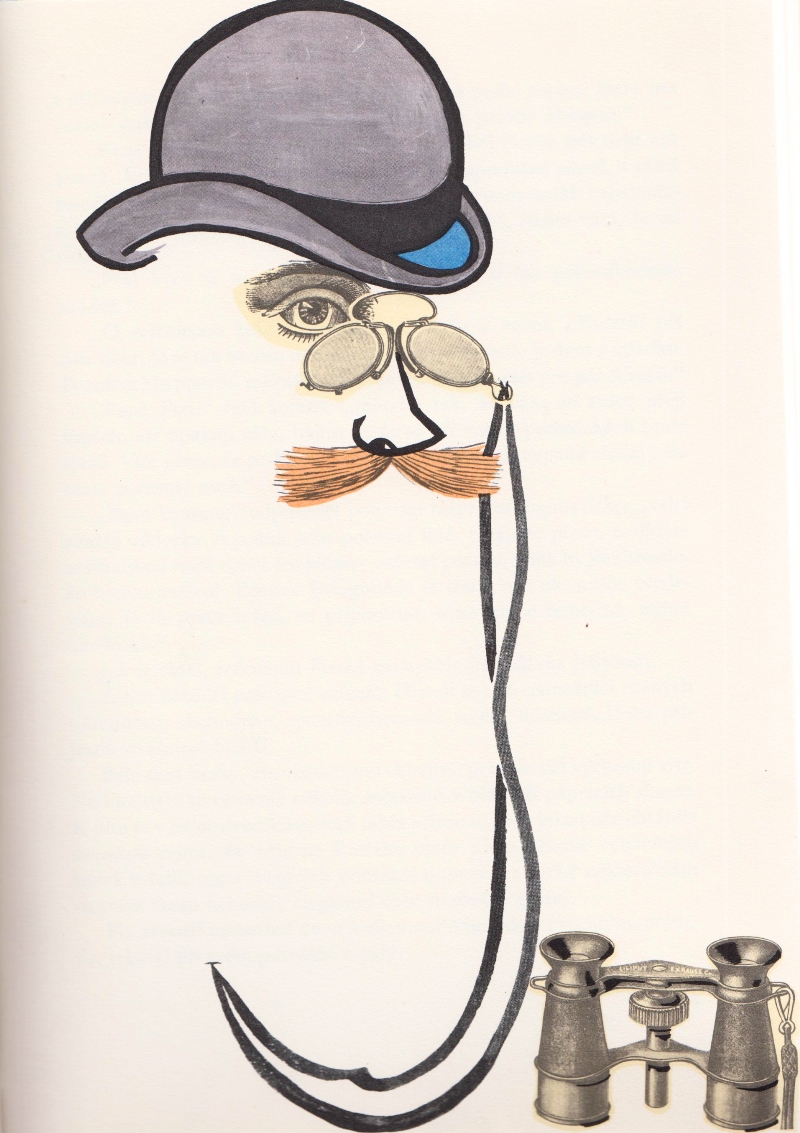

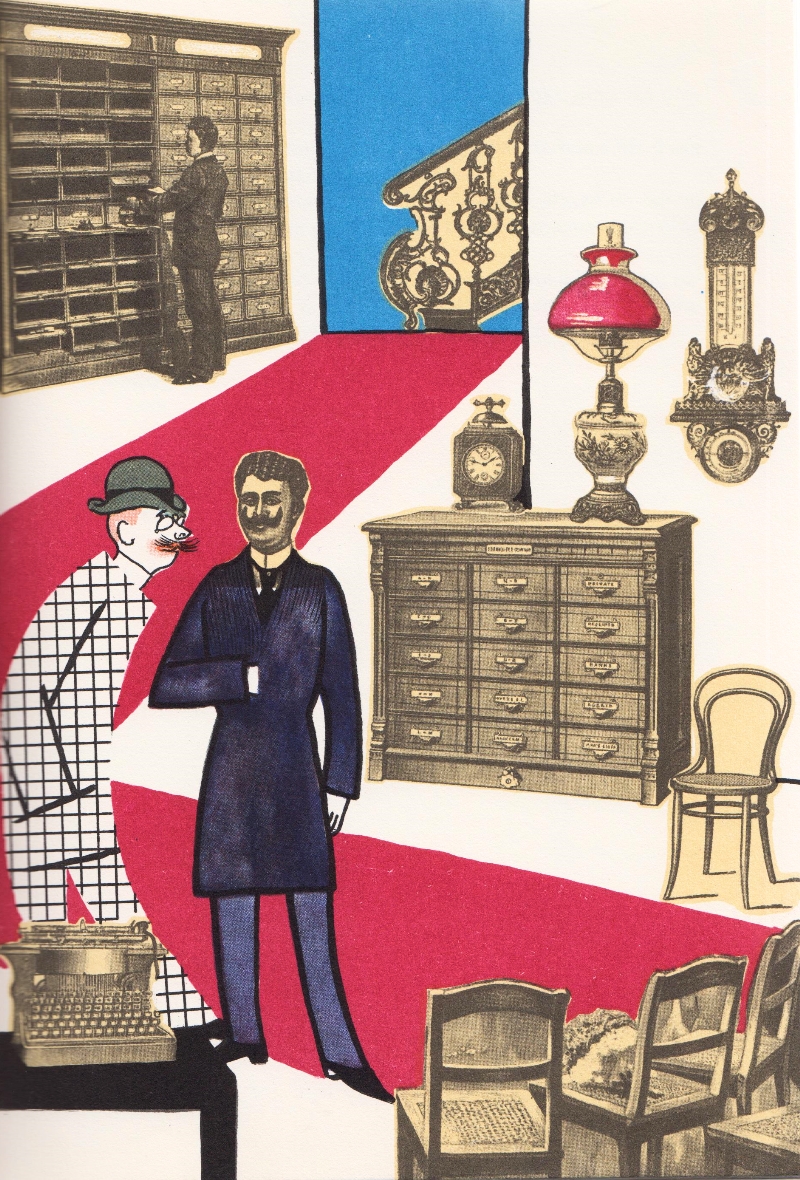

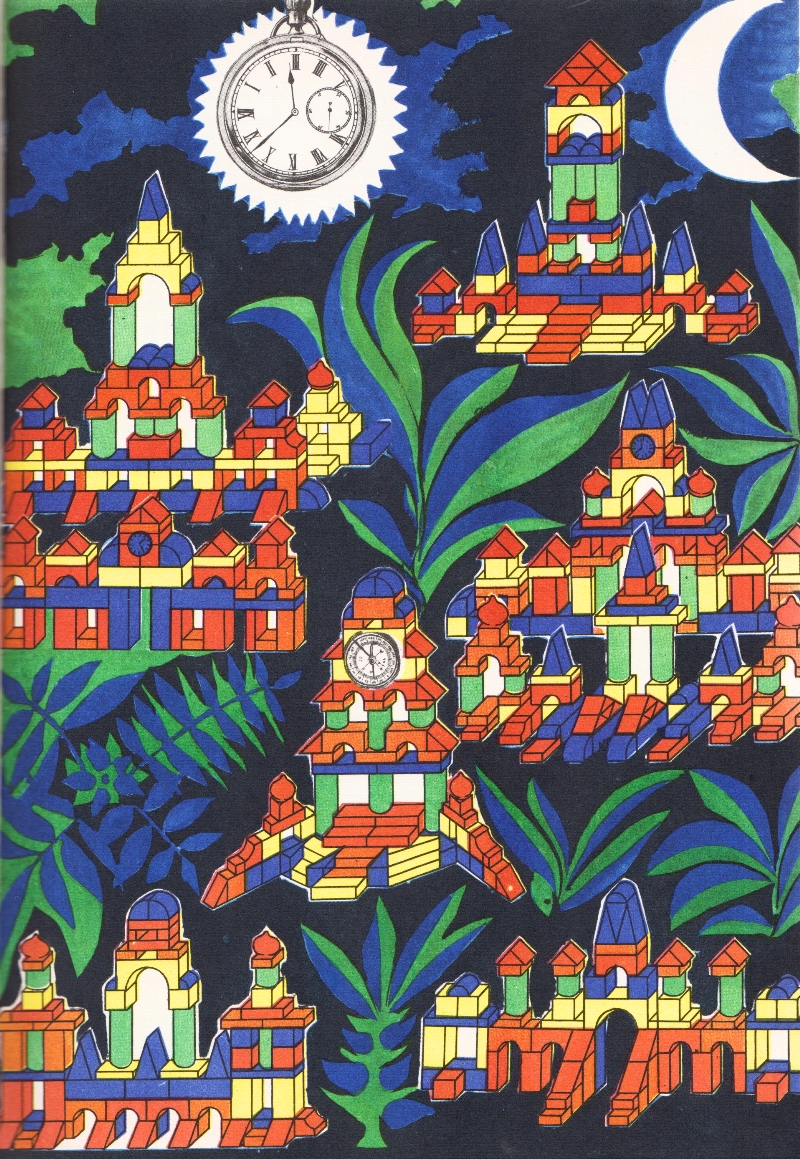

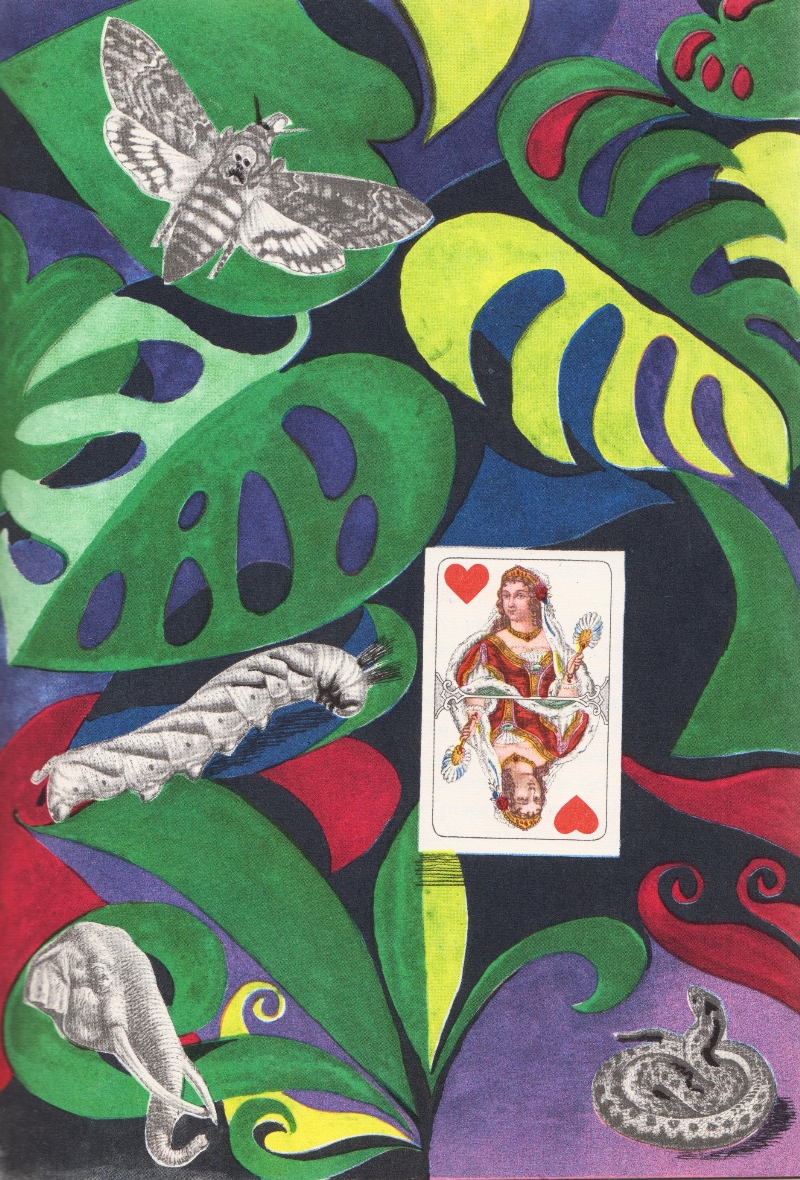

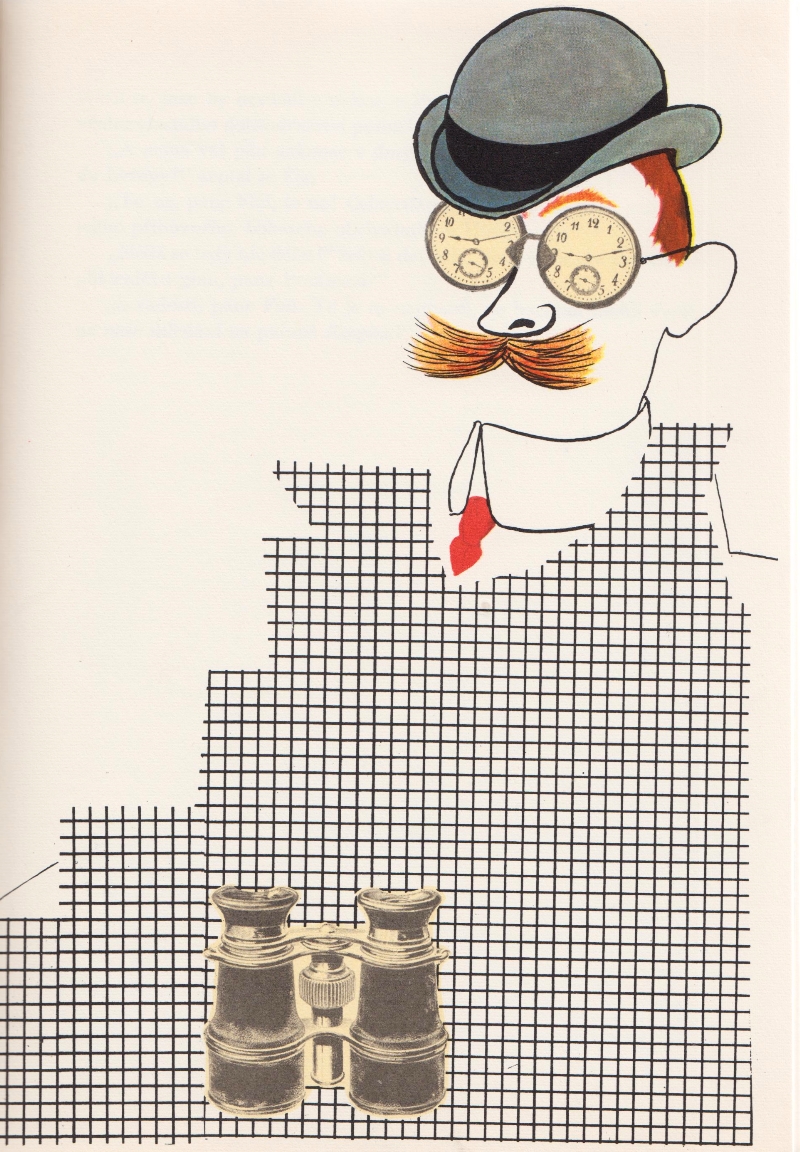

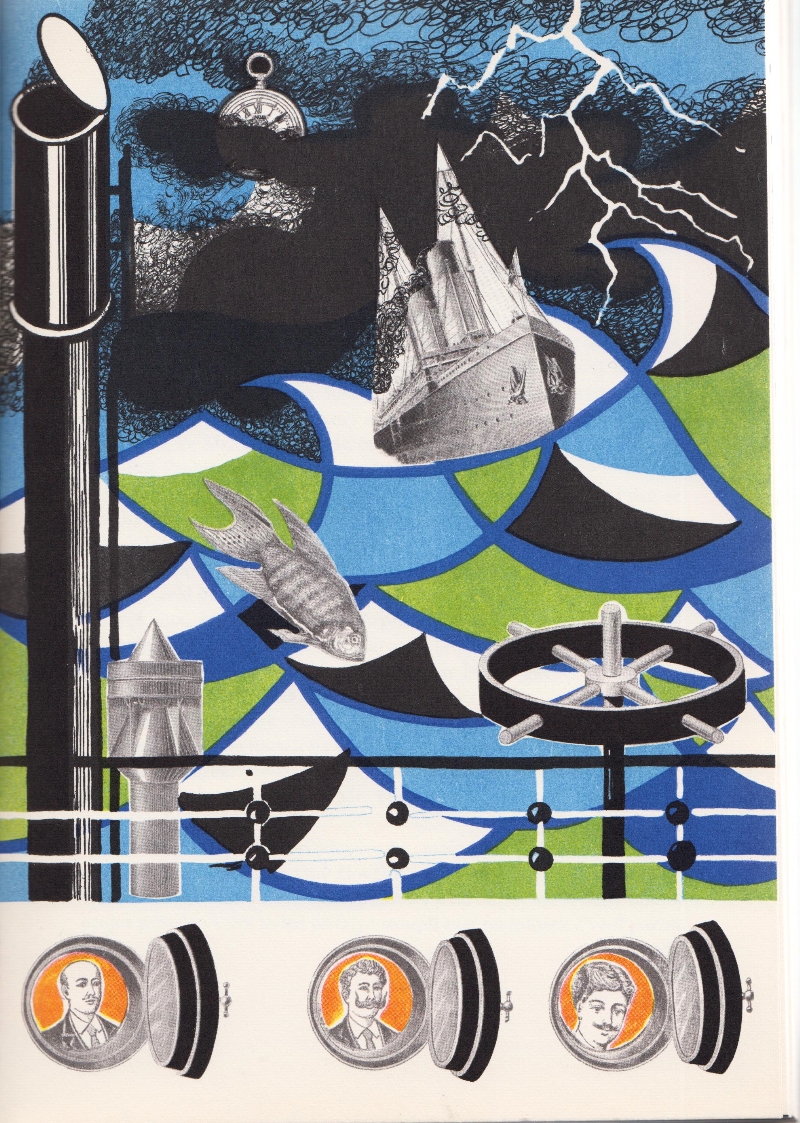

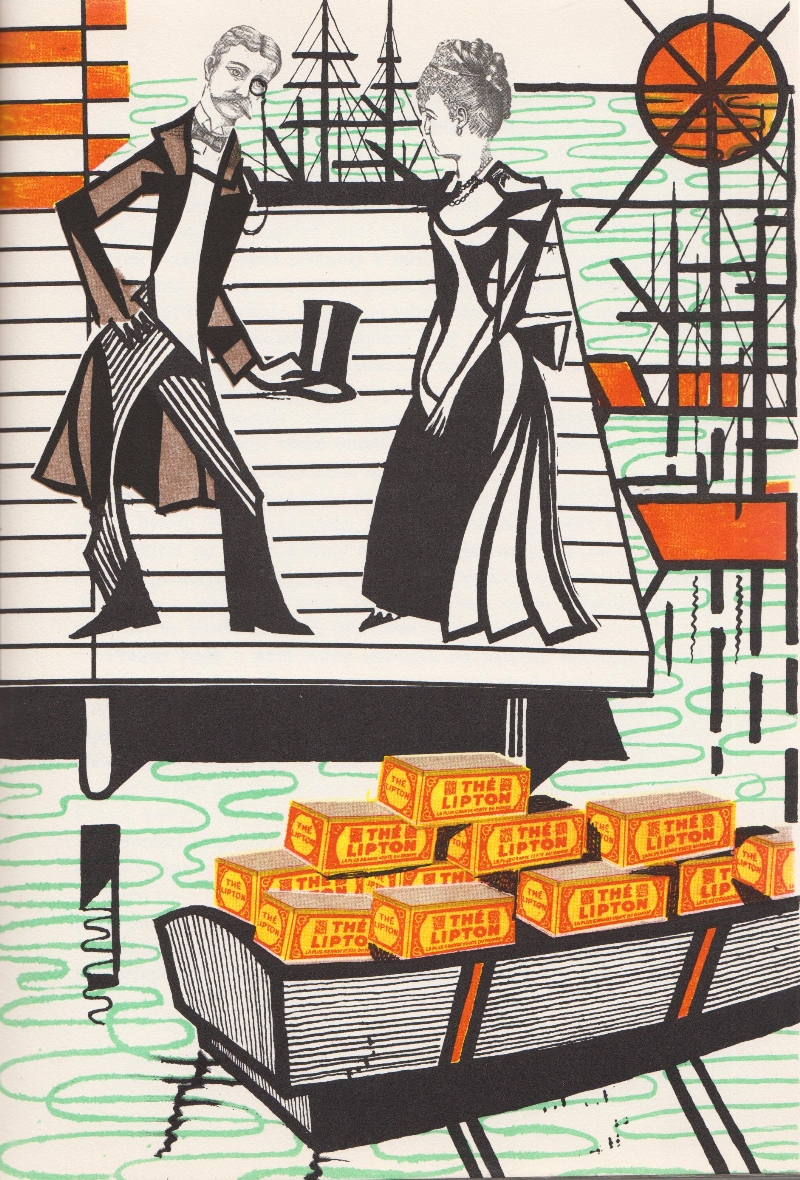

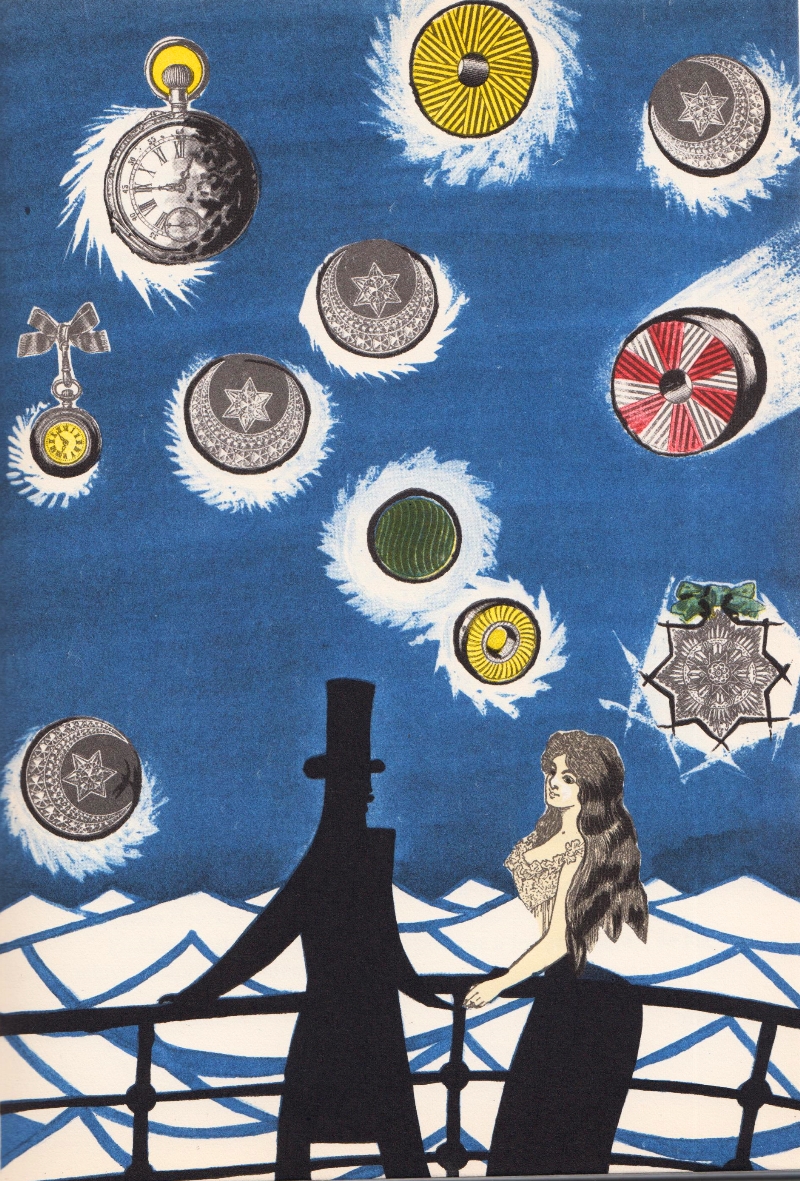

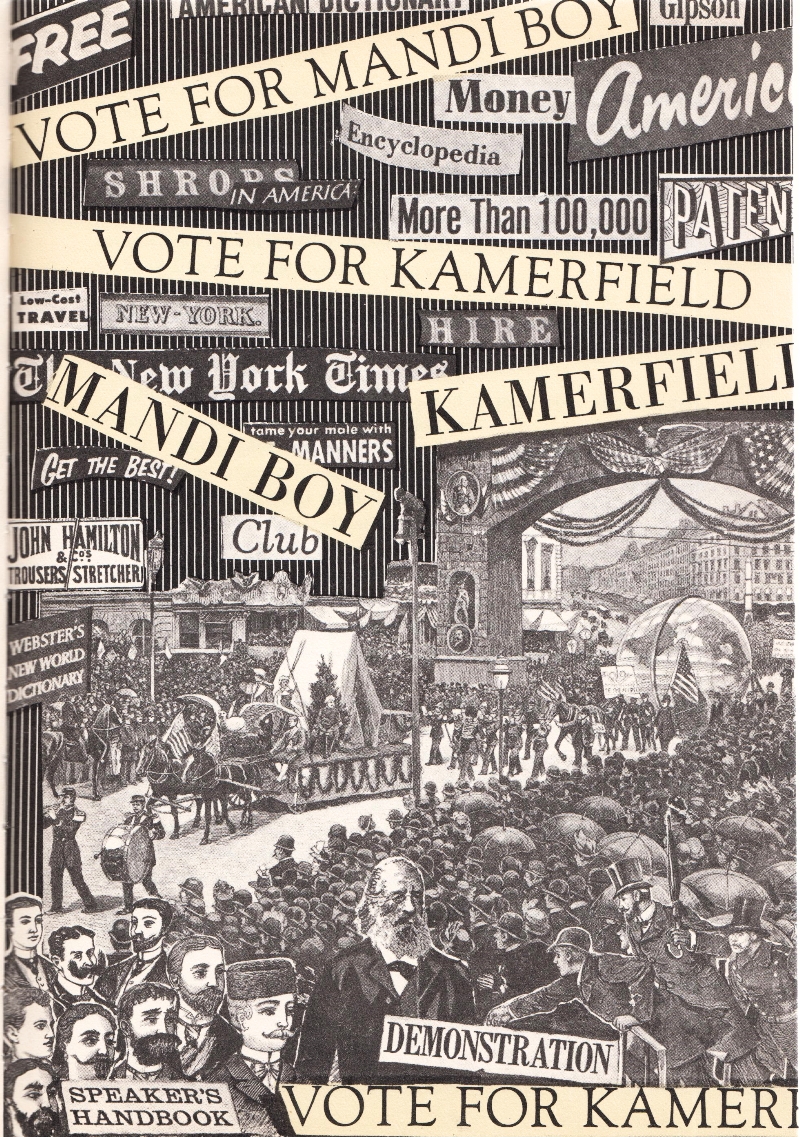

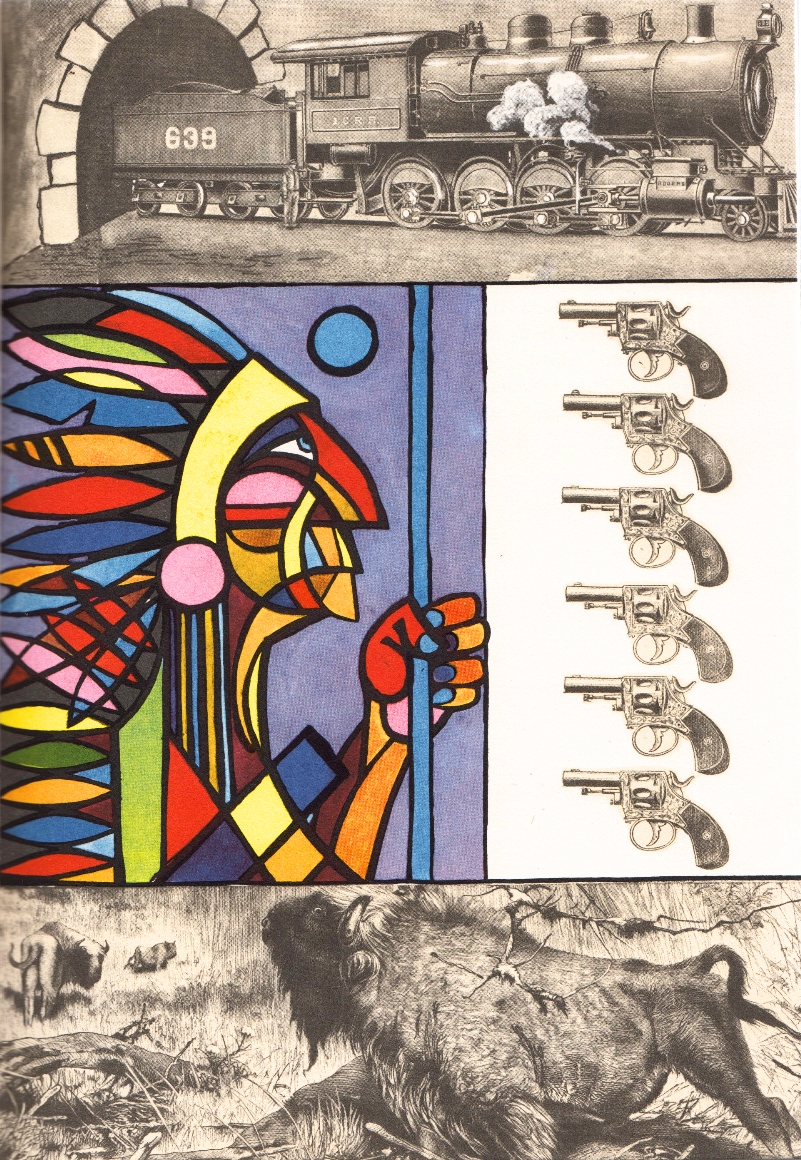

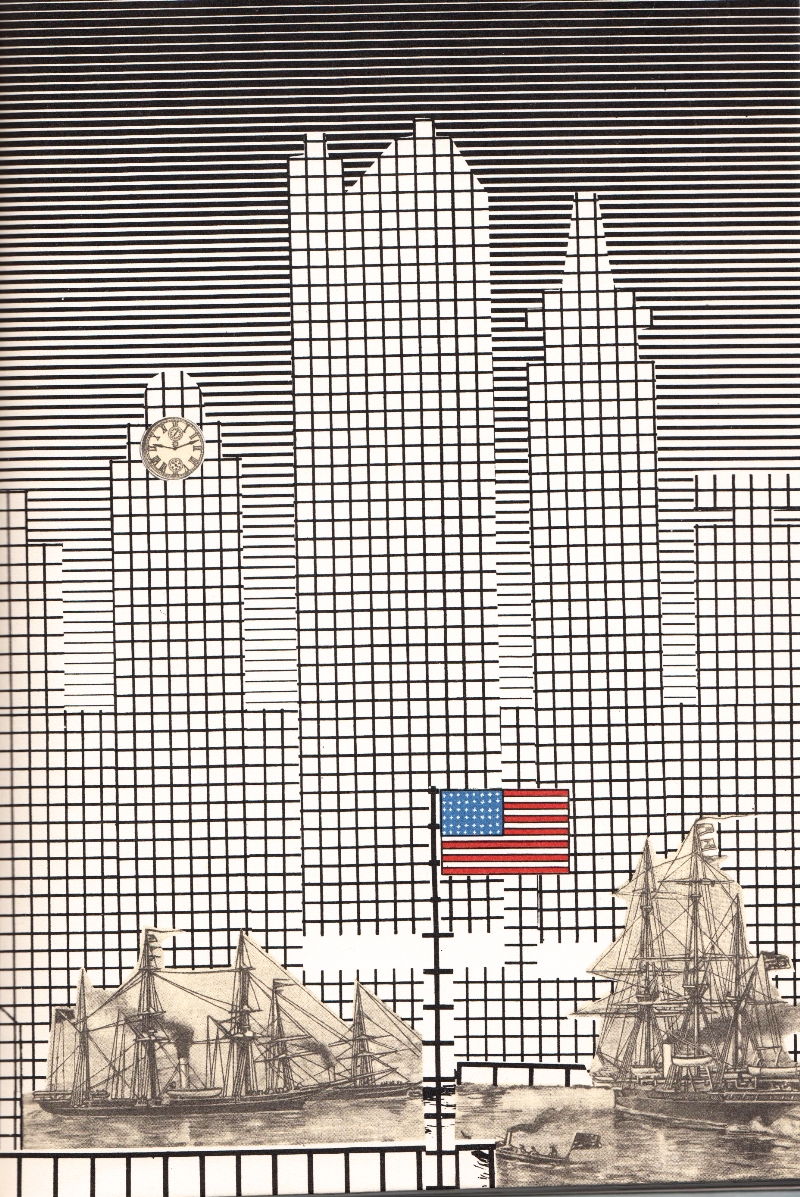

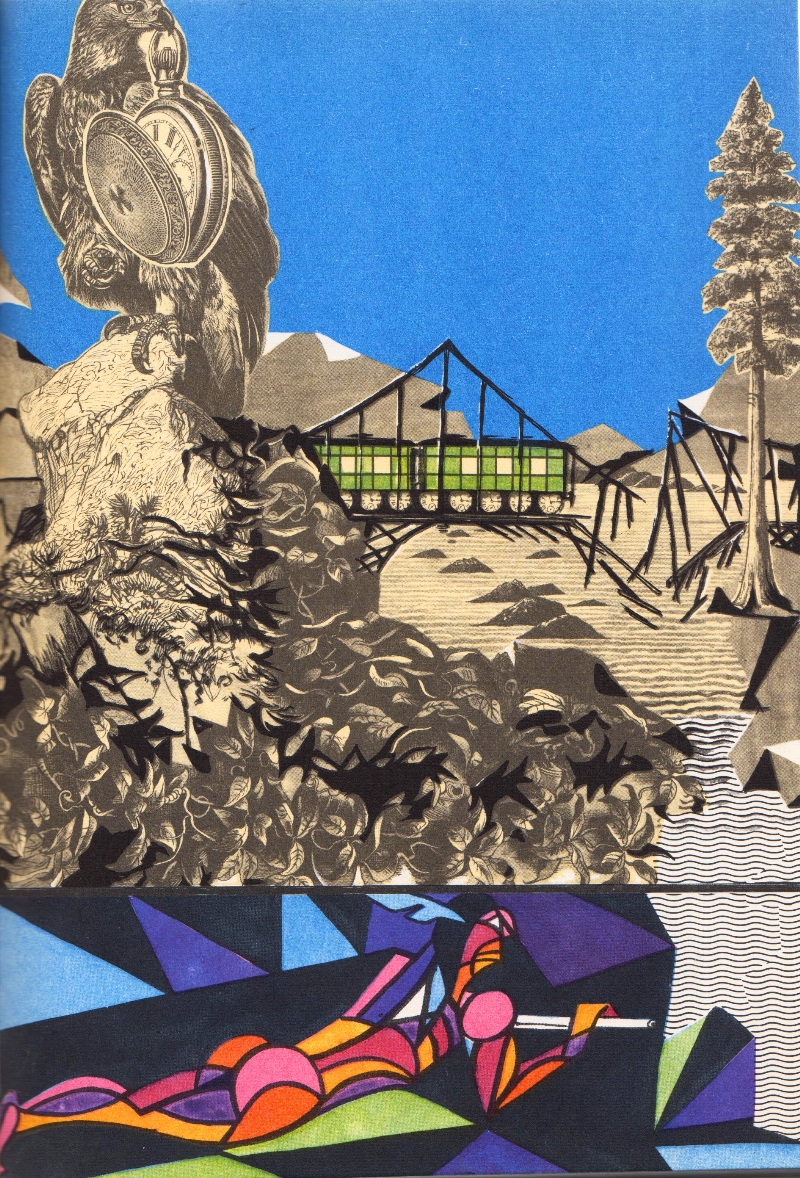

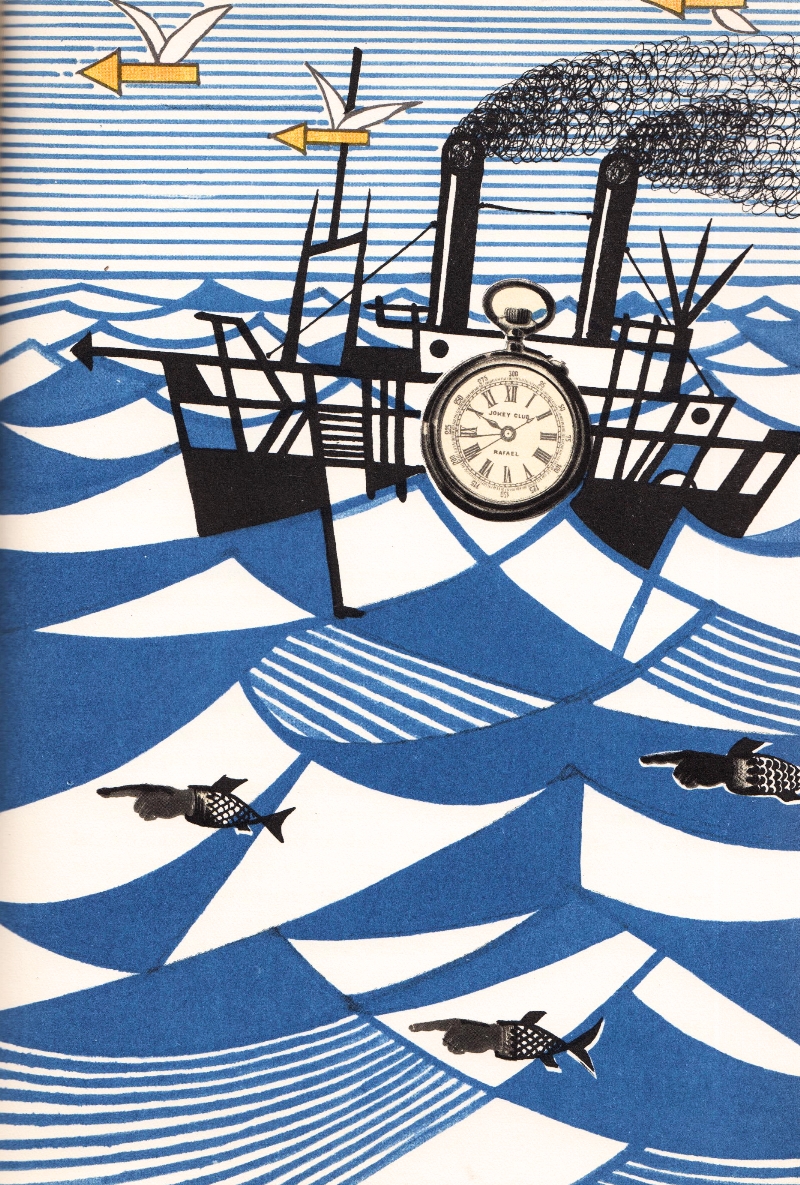

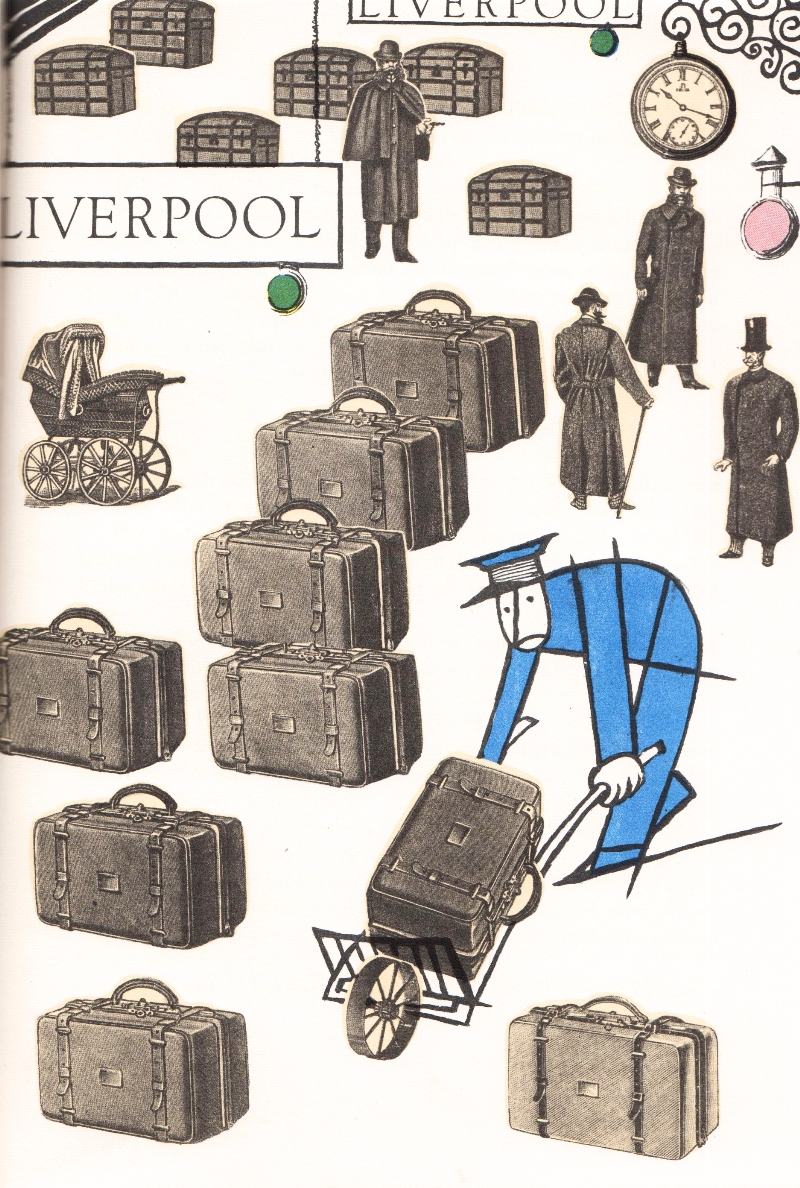

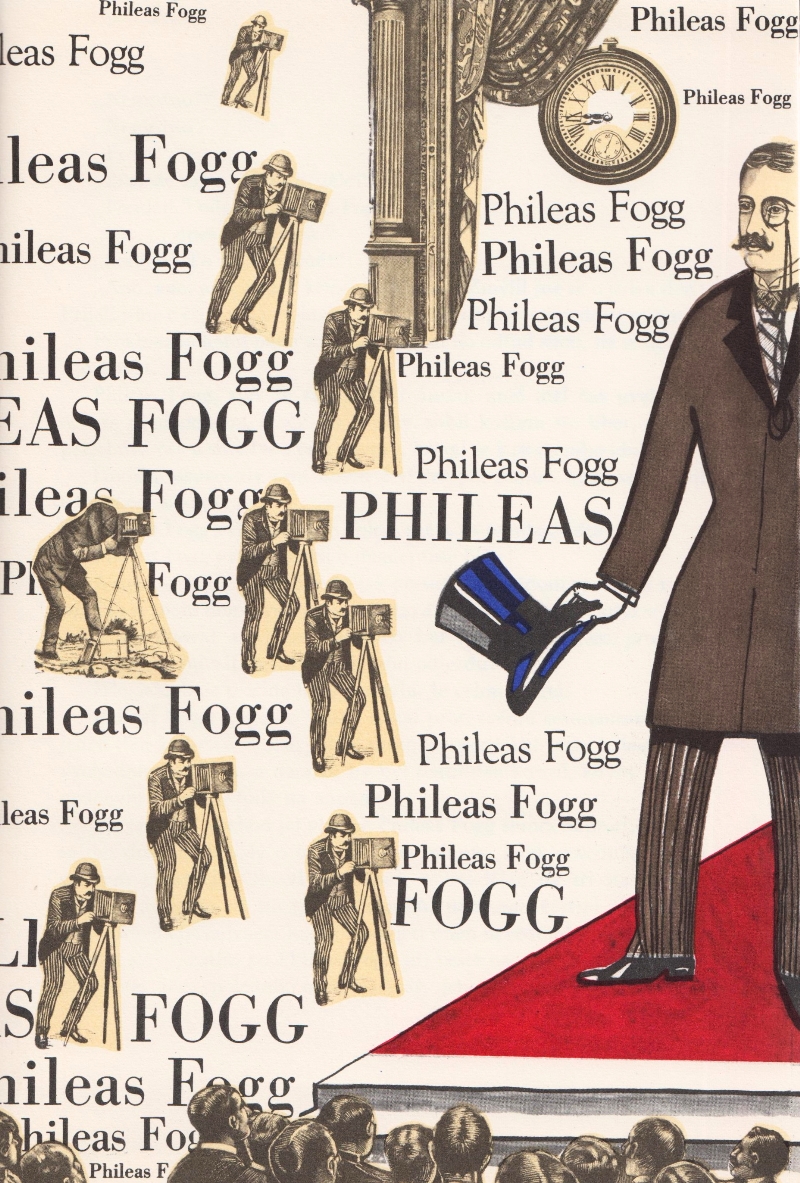

These illustrations by Adolf Hoffmeister appear in Cesta Kolem Světa za Osmdesát Dní, a 1959 Czech edition of Jules Verne’s book Around the World in Eighty Days (1873). Hoffmeister’s busy, assertive and bold collages are infused with energy.

Hoffmeister’s was once an advocate of Dada, the art movement that produced odd and jarringly incongruous juxtapositions of images and words. But in this work, he’s embraced the book’s linear narrative. Every image reflects a passage in the story; and lest you lose track of the essential plot driver – Phileas Phogg has 80 days to circumnavigate the globe – Hoffmeister includes the image of a watch (an identical watch) in nearly every panel. Bit surreal? It’s meant to be. Hoffmeister was also a surrealist.

In Andre Breton’s Manifeste du Surréalisme (1930), he “defined ‘surreality’ as the reconciliation of the reality of dreams with the reality of everyday life into a higher synthesis”. Fogg might be lost in dreamy love as he stands with Aouda, the widowed princess whose life he saves, but above the mesmeric waves the strikingly weird sky features that ticking watch.

Hoffmeister (5 August 1902 – 24 July 1973) was a man of talent. His obituary in the New York Times declared “CZECH ARTIST, DEAD”. But as this biography in Equus shows, he as much more:

Adolf Hoffmeister (1902-1973) was a Czech writer, journalist, playwright, painter, caricaturist, translator, diplomat, lawyer, and traveller. In 1920 he became the youngest co-founder of the Devětsil art group. In 1922 he made the first of the many journeys to Paris, where he regularly met with the international arts scene, many of whose representatives he would interview for Czech press.

In 1927 the Liberated Theatre staged his dadaist plays, in 1928 he had the first solo exhibition in Paris at the Gallerie d’Art Contemporain. In the 1930s, the legal office he worked at represented many of the German exiles fleeing Nazism including Thomas Mann.

As member of the Mánes Association of Fine Arts, he was instrumental in introducing and defending the anti-Nazi photomontage artwork of John Heartfield.

He himself fled Nazism in 1939 for Paris, where he was interned for 7 months, then via a Morocco concentration camp, in 1941 he reached New York. After WW2 he returned to Prague and joined the Communist party and went on to work in diplomacy and the academia. Following his pro-reform interventions in August 1968, he was banned from public life and spent his final years in obscurity.

Granta adds that Hoffmeister edited one of the main Czech daily newspapers, Lidové noviny (1928-30) and the main literary paper, Literární noviny (1930-32):

Hoffmeister set up an anti-fascist magazine, Simplicus, in the 1930s after the German satiric magazine Simplicissimus was banned by the Nazis. He also wrote the libretto for a children’s opera, Brundibar, with music by the Czech composer Hans Krása in 1938; the opera was performed fifty-five times by children in Terezín concentration camp where Krása was interned…

After the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia, Hoffmeister emigrated to France once again in 1969, but decided to return in 1970. He died three years later in the Orlický mountains, judged by the regime to be a non-person.

Hoffmeister also translated James Joyce’s Anna Livia Plurabelle.

Via Tres Bohemes,

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.