‘Alma, tell us / All modern women are jealous. / Which of your magical wands / Got you Gustav and Walter and Franz?”

– Tom Lehrer

Alma Mahler, circa 1908

Oskar Kokoschka (1 March 1886 – 22 February 1980) was an Austrian artist, poet, playwright and teacher who kept a handmade, life-sized doll fashioned to look and feel like the his former lover Alma Mahler (nee Alma Maria Schindler; 31 August 1879 – 11 December 1964). Alma was a musician in Vienna who married, in order: the composer Gustav Mahler; the founder of the Bauhaus, Walter Gropius (after testing the fluids with an affair and praising him as “the true Aryan type. The only man who was racially suited to me. All the others who fell in love with me were little Jews”); and finally the Jewish writer Franz Werfel, whom she tormented with her rampant antisemitism. She also got off with pretty much any man worth knowing in central Europe, including the artist Gustav Klimt (July 14, 1862 – February 6, 1918), who gave her her first kiss at 17.

Alma Mahler liked older men. And they liked her. The humorist Tom Lehrer admired her, too, albeit after her death, and having read her obituary put her story to song a year later in 1965. That obituary in the New York Times pointed to a life well lived:

Mrs. Alma Mahler Werfel, widow of the writer Franz Werfel and earlier of the composer Gustav Mahler, died yesterday in her apartment at 120 East 73d Street…

Mrs. Werfel, who was once described as “the most beautiful girl in Vienna,” recalled in her autobiography that she had always been attracted to genius. She noted that she had once confided to her first husband, Mahler, that what she really loved in a man were his achievements.

…

She was a 21-year‐old music student in 1902 when she met Mahler, who was 41 years old and director of the Court Opera House…

While still married to the composer, she met Walter Gropius, then a little‐known architect. She described him in her diary as an “extraordinarily handsome German,” and added that the night of their first meeting wore into sunrise. “There remained no doubt,” she wrote, “that Walter Gropius was in love with me and expected me to love him.”

Mahler found out about their affair, brought the architect to their home and asked Alma to make a choice. She chose to remain with the composer, but Mr. Gropius continued to write love letters to her. She said in her book “And the Bridge Is Love,” published in 1958, that Mahler read Mr. Gropius’s correspondence and “wrote beautiful poems about it”…

While still married to Gropius she met Franz Werfel and had a son by him. The child died in infancy.

Mr. Gropius and Alma finally agreed to a divorce in 1918. She then moved in with Werfel, and they were married in July, 1929…

She also wrote that other great men who were in love with her were Dr. Paul Krammerer, the biologist, and Ossip Gabrilowitsch, the Russian pianist and conductor who later married Mark Twain’s daughter.

Werfel and Alma fled Nazi Germany in the late nineteen thirties, their experiences prompting Franz to write “The Song of Bernadette” and “Jacobowsky and the Colonel.” They came to the United States in 1940 and settled in California, where Werfel died in 1945. She moved to New York in 1952.

Here’s a little lyrical lightness before we get to Oskar’s tortured heart and the less commonplace stuff:

Unlike her other lovers, Kokoschka was Alma’s junior. He saw her and in an instant was riled with violent passion. “Suddenly,” Alma reported of their first meeting in 1912, “he pulled me into his arms. For me it was a strange, almost shocking and violent hug.”

In Alma Mahler, Muse to Genius : From Fin-de-Siècle Vienna to Hollywood’s heyday by Karen Monson (1983), we read that having squired Mahler, Kokoschka was more than a tad possessive towards her. Lest we think hers a benign presence, Edward Lucie-Smith, notes in Lives of the Great 20th Century Artists: “They travelled to Italy together, and on one occasion visited the Naples aquarium. Kokoschka watched an insect sting and paralyse a fish, before devouring it, and at once associated the scene with the woman by his side.” In The Artist’s Wife (2001), Max Philips narrates: “At the age of 32, she takes up with a wild and frighteningly possessive painter named Oskar Kokoschka, who is 26. She taunts him, telling him she’ll marry him only if he produces a masterpiece.” Such was the woman who judged men by their achievements.

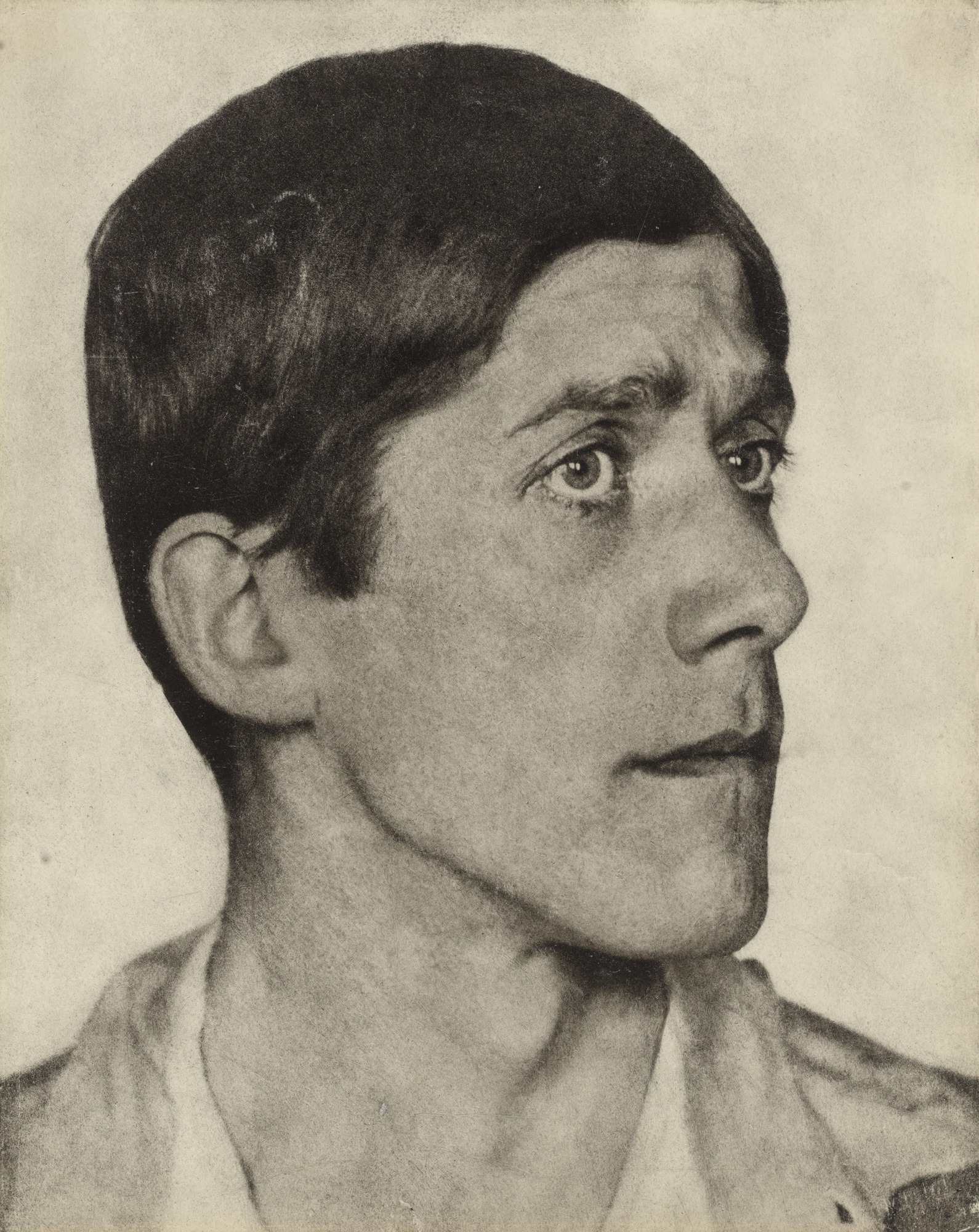

Oskar Kokoschka – 1919

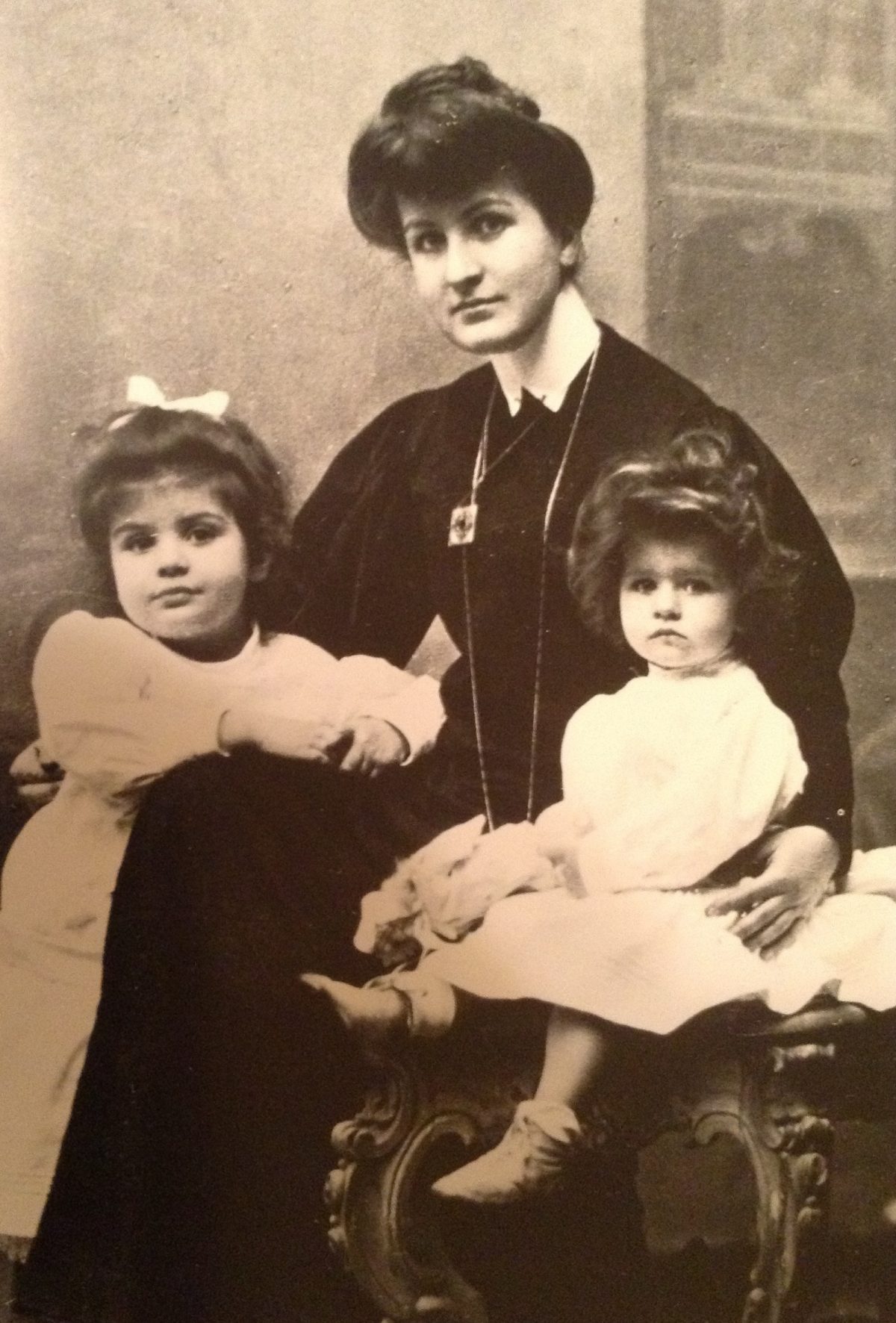

Alma and Gustav Mahler

Alma Mahler with her daughters Maria (at left) and Anna (at right), cabinet card photo circa 1906

And before we get to the oddness, the Nonist has more:

Alma became pregnant and, against Oscar’s wishes, has the child aborted. Oscar is crushed. At the outbreak of World War I in 1914 he volunteers and serves with the Austrian army. In 1915, while stationed in Russia, Oscar receives a serious injury via unfriendly bayonet. He returns from the front to find Alma has married an old flame, architect Walter Gropius. Oscar is double-crushed. In 1918, underlining military doctor’s previous assessment of him as “mentally unstable,” he reacts to all this heartache the way any good, obsessive, expressionist painter would.

Which was..? Yes. Spot on. Kokoschka commissioned doll-maker Hermine Moos to create a life-sized Alma Mahler doll to her exact, anatomically accurate specifications. In 1918, the artist sends dear Hermine his order:

“Yesterday I sent a life-size drawing of my beloved and I ask you to copy this most carefully and to transform it into reality. Pay special attention to the dimensions of the head and neck, to the ribcage, the rump and the limbs. And take to heart the contours of body, e.g., the line of the neck to the back, the curve of the belly. Please permit my sense of touch to take pleasure in those places where layers of fat or muscle suddenly give way to a sinewy covering of skin. For the first layer (inside) please use fine, curly horsehair; you must buy an old sofa or something similar; have the horsehair disinfected. Then, over that, a layer of pouches stuffed with down, cottonwool for the seat and breasts. The point of all this for me is an experience which I must be able to embrace! Can the mouth be opened? Are there teeth and a tongue inside? I hope so!”

Oskar Kokoschka als Dragoner, c. 1915

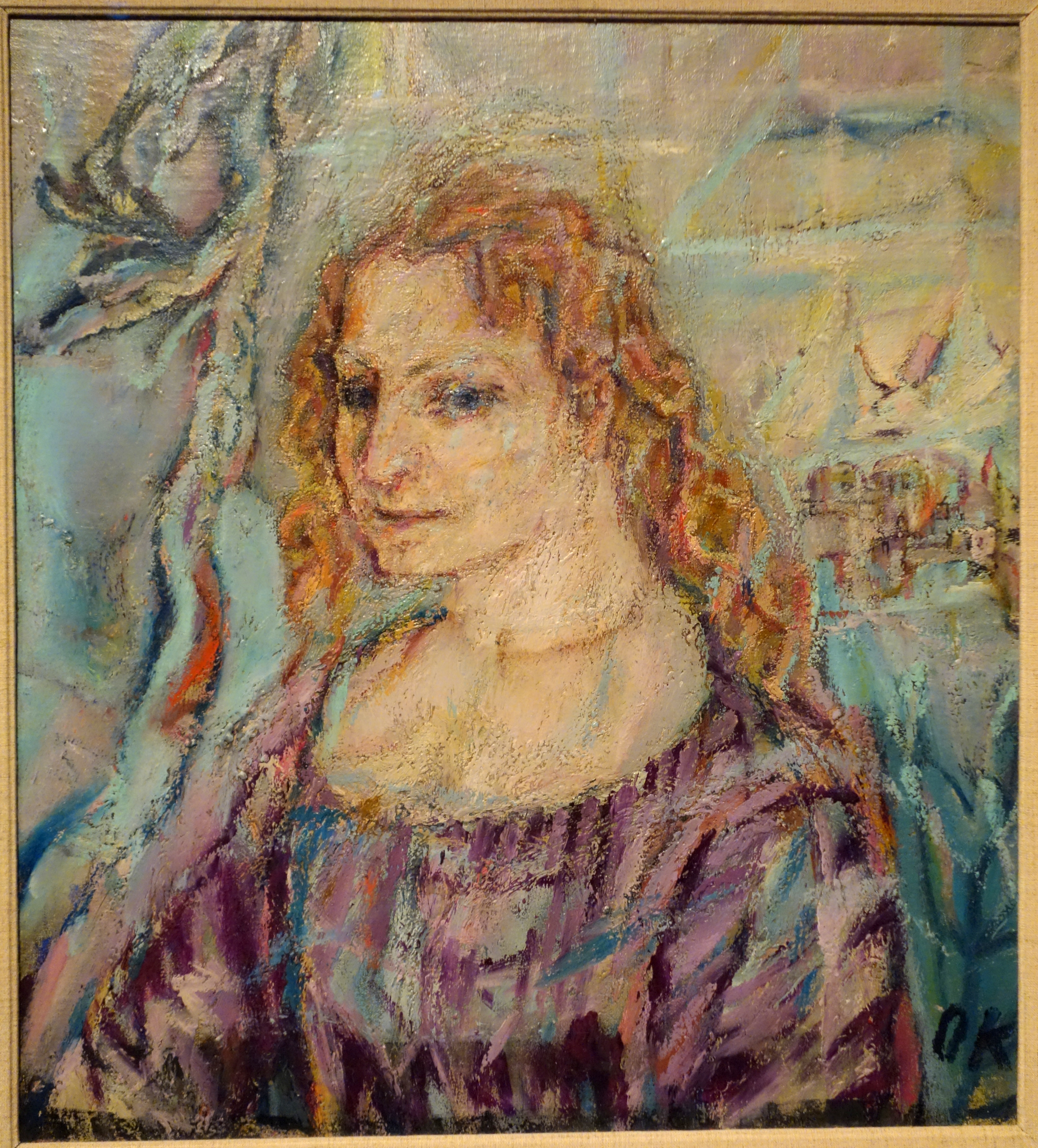

Alma Mahler by Oskar Kokoschka, 1912

The Bride of the Wind (Die Windsbraut) (or The Tempest) is a 1913–1914 painting by Oskar Kokoschka. The oil on canvas work is housed in the Kunstmuseum Basel. Kokoschka’s best known work, it is an allegorical picture featuring a self-portrait by the artist, lying alongside his lover Alma Mahler.

It took Hermine Moos nine months to give birth to the Alma doll. Kokoschka grew impatient. He put pen to paper:

“I would die of jealousy if some man were allowed to touch the artificial woman in her nakedness with his hands or glimpse her with his eyes! When shall I be able to hold all this in my hands?”

He knew other women, notably a maid named Hulda who carved his initials into her breasts. But… as he told Hermine:

“I was preoccupied with anxious thoughts about the arrival of the doll, for which I had bought Parisian clothes and underwear. I wanted to have done with the Alma Mahler business once and for all, and never again to fall victim to Pandora’s fatal box, which had already brought me so much suffering.”

Alma Mahler II was delivered to Kokoschka in February 1919, upon which, according to what the artist told his friend, the photographer Brassaï, his butler saw it and suffered a stroke. Kokoschka was madly excited, writing in his diary:

“In a state of feverish anticipation, like Orpheus calling Eurydice back from the Underworld, I freed the effigy of Alma Mahler from its packing. As I lifted it into the light of day, the image of her I had preserved in my memory stirred into life.”

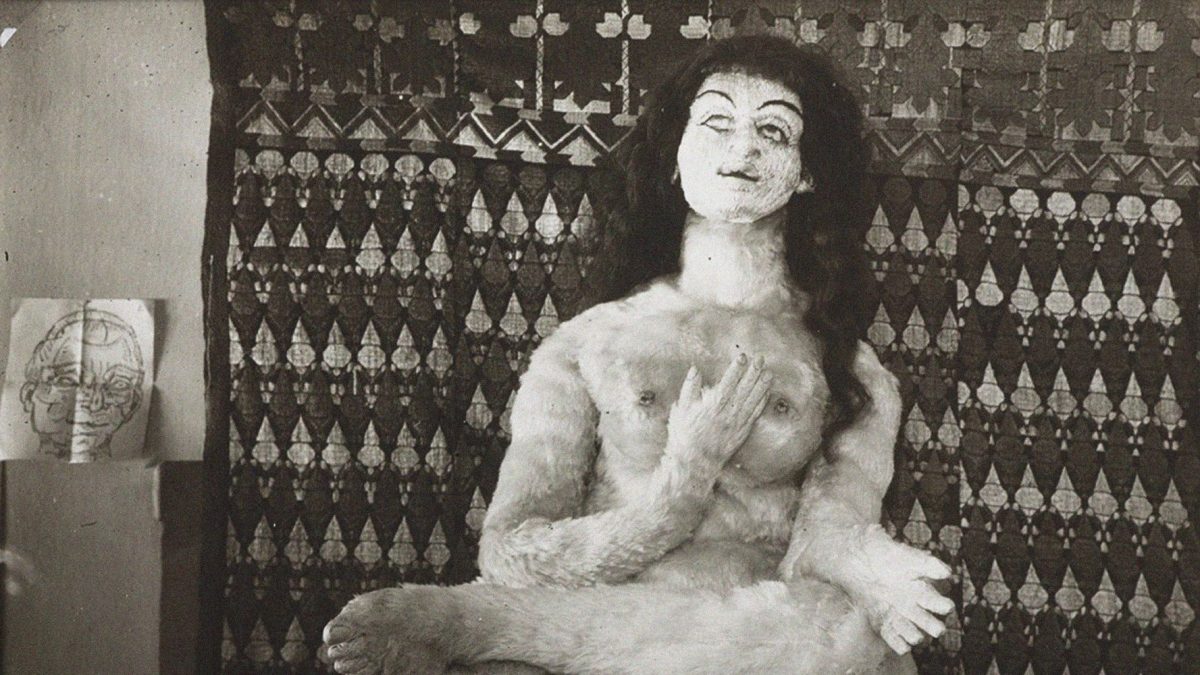

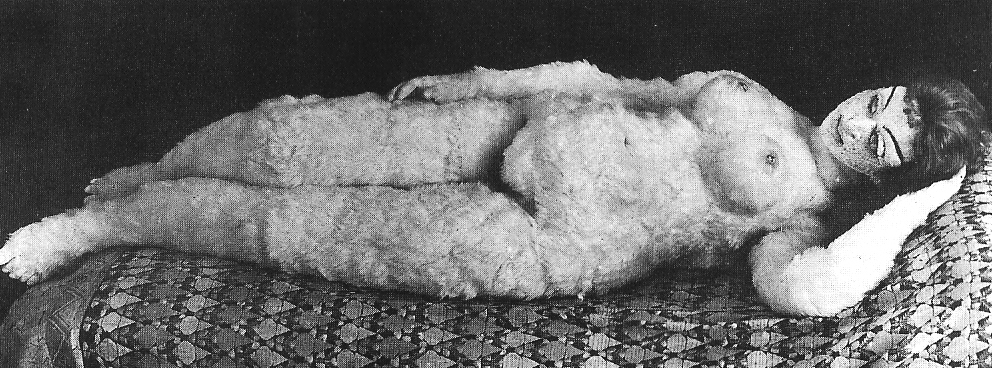

Alma Mahler doll

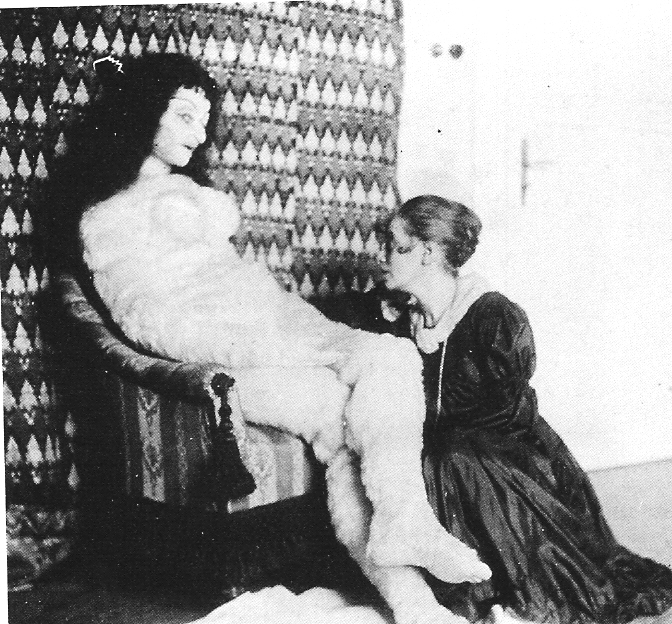

Hermine Moos and the Alma Mahler doll

He liked it? No, not much but it’d have to do. Buyer beware. He wrote once more to Hermine:

“I was honestly shocked by your doll which, although I was long prepared for a certain distance from reality, contradicts what I demanded of it and hoped of you in too many ways! The outer shell is a polar-bear pelt, suitable for a shaggy imitation bedside rug rather than the soft and pliable skin of a woman. The result is that I cannot even dress the doll, which you knew was my intention, let alone array her in delicate and precious robes. Even attempting to pull on one stocking would be like asking a French dancing-master to waltz with a polar bear!”

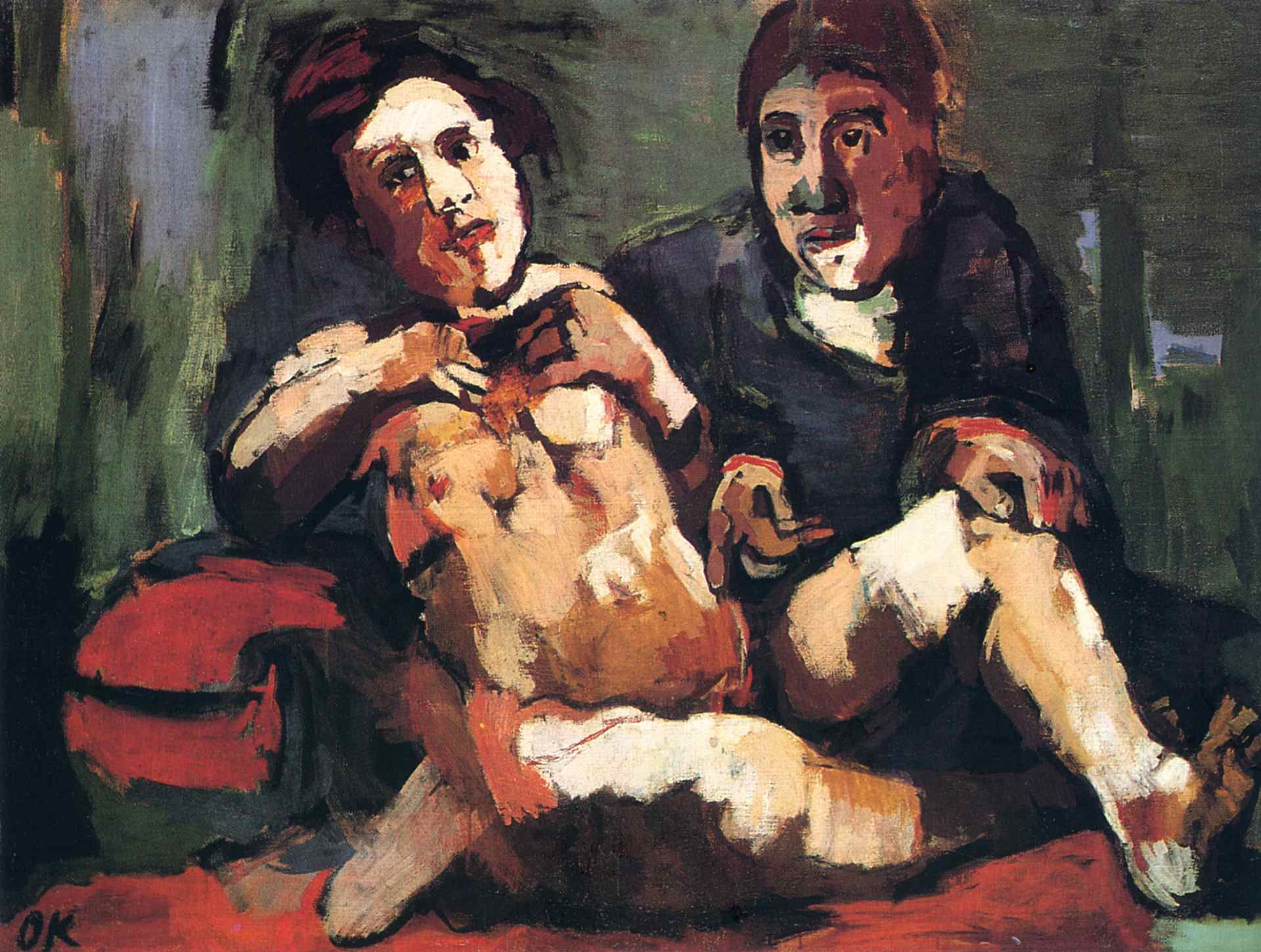

Designed by Moos, the doll was a work of macabre wonder: a swan-skin body (the feathers were still attached) stuffed with sawdust. You can see it in these photos and in approximately 33 of Kokoschka’s artworks. If you’d been around at the time, you might have seen him dining with it in restaurants. But you can’t see the actual Alma Mahler II because Kokoschka murdered her.

Dear diary:

“Finally, after I had drawn it and painted it over and over again, I decided to do away with it. It had managed to cure me completely of my Passion. So I gave a big champagne Party with chamber music, during which my maid Hulda exhibited the doll in all its beautiful clothes for the last time. When dawn broke – I was quite drunk, as was everyone else – I beheaded it out in the garden and broke a bottle-of red wine over its head.”

Self-portrait with Doll, 1921, by Oskar Kokoschka

Kokoschka was deemed an enemy of the state by the Nazis and his work banned as ‘degenerate‘. He married a much younger woman, moved to Cornwall, England, and in 1946 became a British citizen. He regained his Austrian citizenship in 1978.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.