Christopher Payne takes us back to when mental illness was even less understood than it is today in his pictures of former asylums taken between 2002 and 2008. These vast architectural relics cast sinister shadows on the modern human psyche. That was then, we tell ourselves. And it as awful. But an asylum is a refuge. It offers sanctuary and a safe place to be different. The Oxford English Dictionary says an asylum is “a benevolent institution according shelter and support to some class of the afflicted, the unfortunate, or destitute.”

Payne’s pictures show us the afterlife of once thriving buildings, vital and hulking parts of America’s mental health industry.

The late Dr Oliver Sachs writes an introduction to Payne’s book Asylum: Inside the Closed World of State Mental Hospitals.

We tend to think of mental hospitals as “snake pits”—places of nightmarish squalor and abuse—and this is how they have been portrayed in books and film. Few Americans, however, realize these institutions were once monuments of civic pride, built with noble intentions by leading architects and physicians, who envisioned the asylums as places of refuge, therapy, and healing.

For more than half the nation’s history, vast mental hospitals were a prominent feature of the American landscape. From the mid-nineteenth century to the early twentieth, more than 250 institutions for the insane were built throughout the United States; by 1948 they housed over half a million patients. But over the next thirty years, with the introduction of psychotropic drugs and policy shifts toward community-based care, patient populations declined dramatically, leaving many of these massive buildings neglected and abandoned.

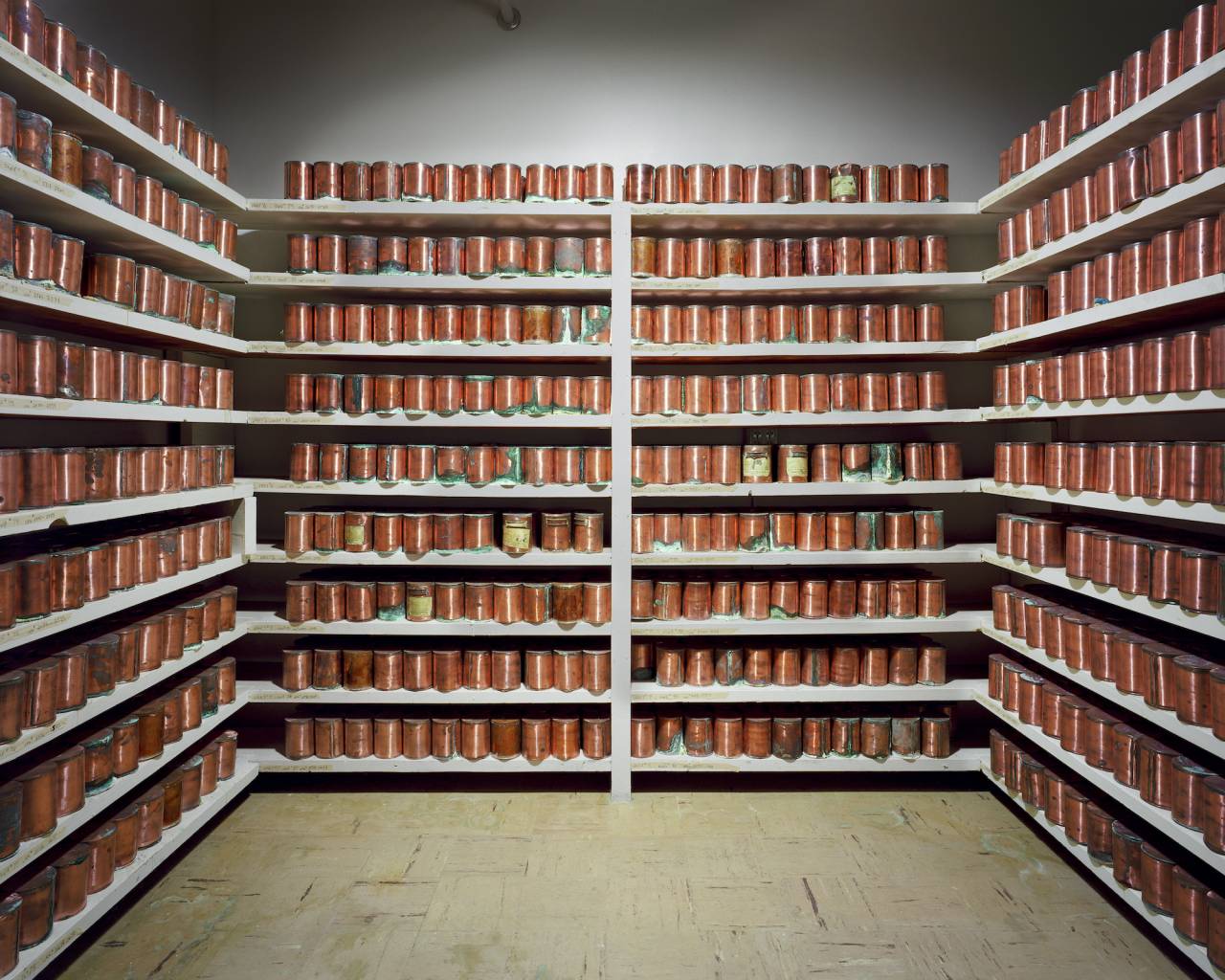

From 2002 to 2008, I visited seventy institutions in thirty states, photographing palatial exteriors designed by famous architects and crumbling interiors that appeared as if the occupants had just left. I also documented how the hospitals functioned as self-contained cities, where almost everything of necessity was produced on site: food, water, power, and even clothing and shoes. Since many of these places have been demolished, the photographs serves as their final, official record.

Sachs wrote in 2009:

….it is salutary to hear the voice of an inmate, one Anna Agnew, judged insane in 1878 (such decisions, in those days, were made by a judge, not a physician) and “put away” in the Indiana Hospital for the Insane. Anna was admitted to the hospital after she made increasingly distraught attempts to kill herself and tried to kill one of her children with laudanum. She felt profound relief when the institution closed protectively around her, and most especially by having her madness recognized. As she later wrote:

Before I had been an inmate of the asylum a week, I felt a greater degree of contentment than I had felt for a year previous. Not that I was reconciled to life, but because my unhappy condition of mind was understood, and I was treated accordingly. Besides, I was surrounded by others in like bewildered, discontented mental states in whose miseries…I found myself becoming interested, my sympathies becoming aroused…. And at the same time, I too, was treated as an insane woman, a kindness not hitherto shown to me.

Dr. Hester being the first person kind enough to say to me in answer to my question, “Am I insane?” “Yes, madam, and very insane too!”… “But,” he continued, “we intend to benefit you all we can and our particular hope for you is the restraint of this place.”…I heard him [say] once, in reprimanding a negligent attendant: “I stand pledged to the State of Indiana to protect these unfortunates. I am the father, son, brother and husband of over three hundred women…and I’ll see that they are well taken care of!”

It’s that photo in particular, taken at the old Hudson River State Hospital in New York, that still confounds Payne:

“For some reason, everyone left their toothbrushes there,” he tells Laura Sullivan, guest host of weekends on All Things Considered. “The fact that this little box of toothbrushes had survived on the wall while the rooms around it were crumbling was incredible.”

Oliver Sachs:

Asylums offered a life with its own special protections and limitations, a simplified and narrowed life perhaps, but within this protective structure, the freedom to be as mad as one liked and, for some patients at least, to live through their psychoses and emerge from their depths as saner and stabler people.

In general, though, patients remained in asylums for the long term. There was little preparation for return to life outside, and perhaps after years cloistered in an asylum, residents became ‘institutionalized’ to some extent, and no longer desired, or could no longer face, the outside world.”

All images: © Christopher Payne

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.