‘Harlotry becomes Audrey Hepburn’ wrote the Manchester Guardian at the beginning of it’s review of Blake Edward’s Breakfast at Tiffany’s in October 1961, before continuing ‘but then anything or everything becomes this enchantress’. To most critics and the movie-going public, Hepburn could almost do no wrong at this stage of her career, even if she was woefully miscast. When the pre-production started on Truman Capote’s novella, originally published by Esquire magazine in November 1958, many people were worried about what exactly Holly Golightly was or did. Including Hepburn herself, “When you publicise this unusual role,” she told Blake Edwards, while they were filming, “please make it clear that I do not play a trollop; I play a kook”. Marilyn Monroe–whose background was far closer to the character in Truman Capote’s original*, especially if you compare it with Audrey’s–had turned down the role on the advice of her acting coach Paula Strasberg who said she shouldn’t play a ‘lady of the evening’. Kim Novak and Shirley MacLaine , eventually regretting it, also said no to the part.

The Paramount publicity department did everything they could to deflect the public from worrying about any hint of prostitution in Hepburn’s role. But they also had to explain what a ‘kook’ was, worried that people might consider it, God forbid, Beatnik terminology:

“She’s a kook, and all that jazz,” they say. But what do they mean, dad?

At the moment, the only authenticated, self-styled kook is Miss Audrey Hepburn who claims to be one as Holly Golightly in Jurow-Shepherd’s Breakfast at Tiffany’s.

Holly Golightly keeps a fish in a birdcage. Holly Golightly takes breakfast on the sidewalk of Tiffany & Co. on Fifth Avenue. Holly Golightly wears clothes designed by Hubert de Givenchy of Paris. Holly has a cat whose name is “Cat.”

But what’s a kook?

Kook is not, as everybody associated with Breakfast at Tiffany’s knows, a beatnik term. Couldn’t be. The star is Audrey Hepburn, not Tawdry Hepburn.

Playboy magazine asked Truman Capote during an interview in 1968 about the character he had created in his novella published originally by Esquire magazine in November 1958:

Golightly was not precisely a call-girl she had no

job, but accompanied expense-account men to the best restaurants

and night dubs, with the understanding that her escort was obligated

to give her some sort of gift, perhaps jewellery or a check. Holly was

always running to the girl’s room and asking her date, “May I have a

little powder-room change?” And the man would give her $50.

In Capote’s original novella, Holly Golightly tells the nameless narrator:

I haven’t anything against whores. Except this: some of them may have an honest tongue but they all have dishonest hearts. I mean, you can’t bang the guy and cash his cheques and at least not try to love him.

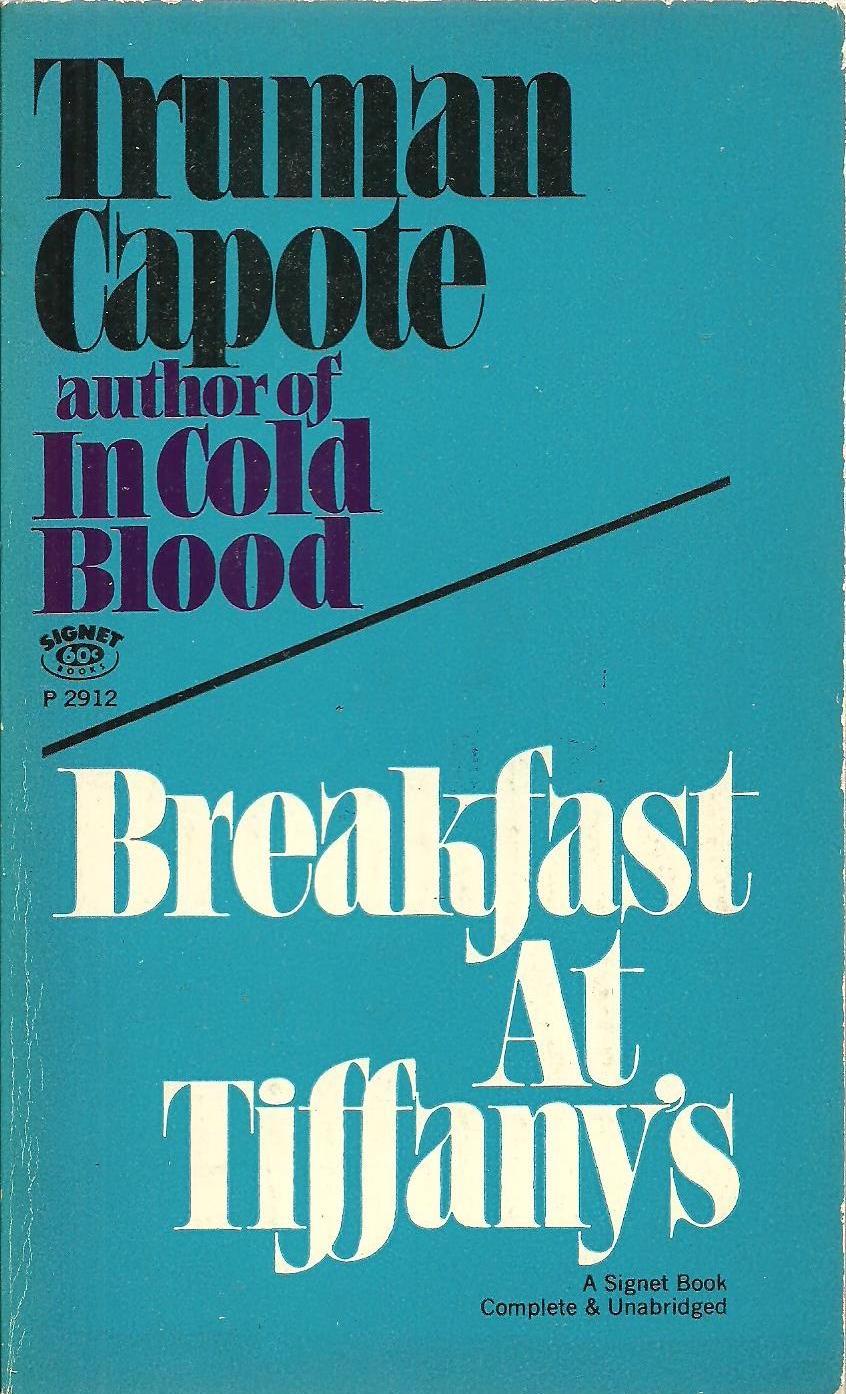

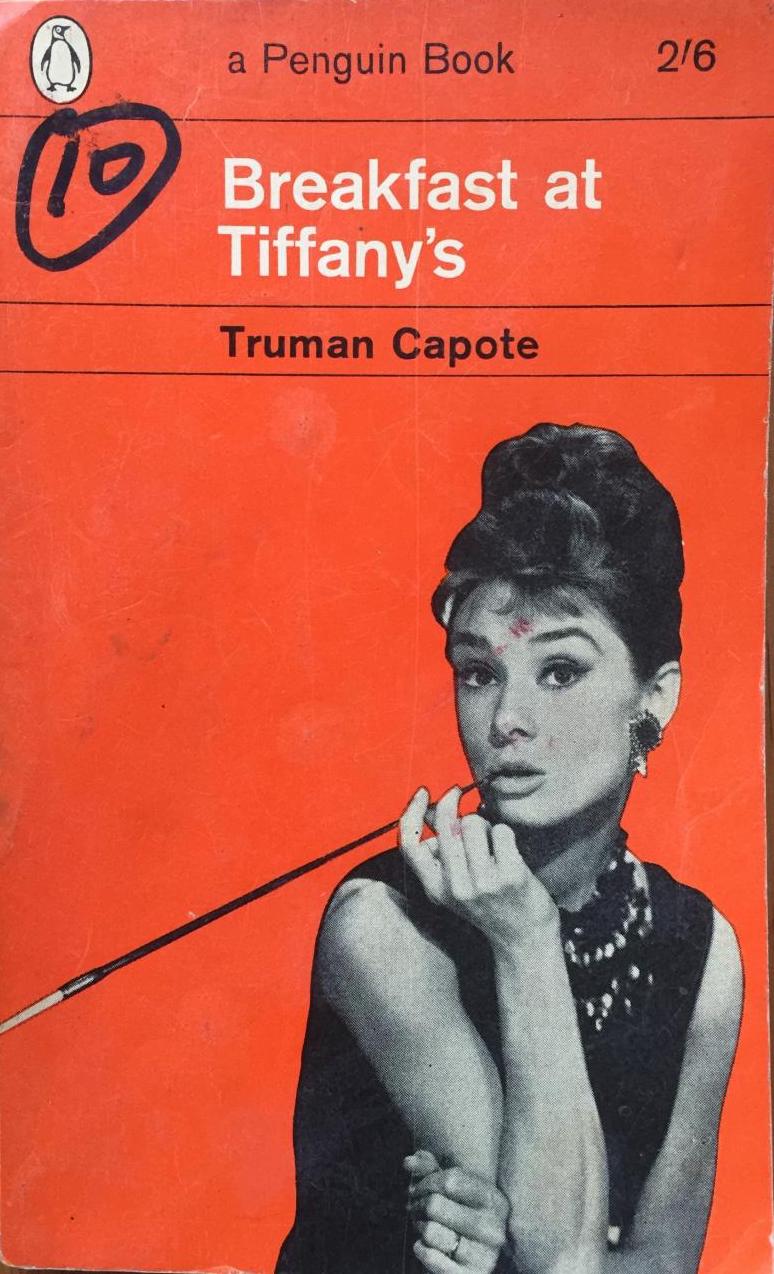

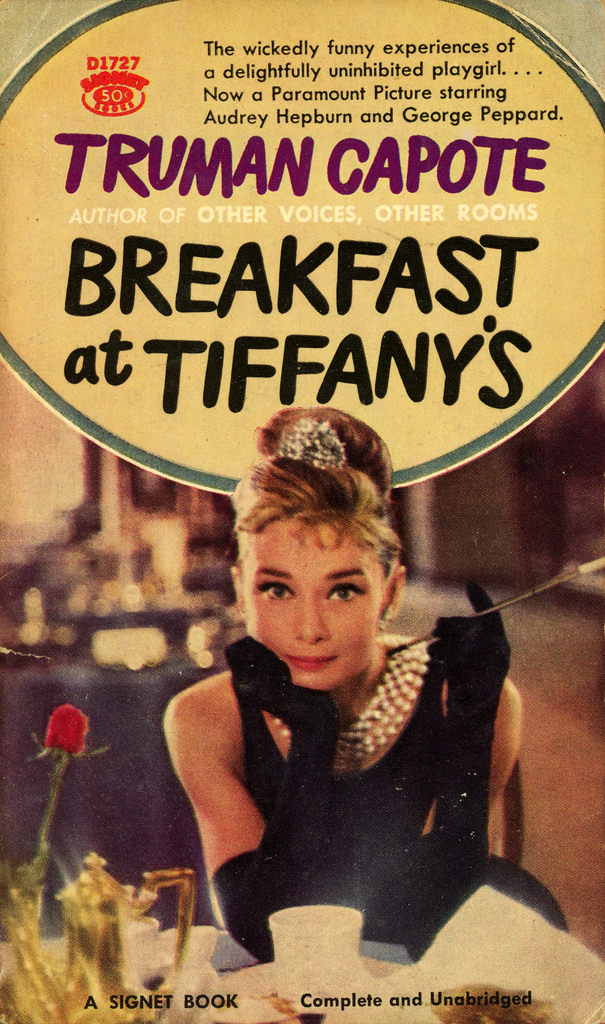

Capote’s original story initially appeared in the November, 1958 issue of Esquire magazine. Shortly afterwards, a collection of the novella and three short stories by Capote was published by Random House and subsequently by Signet.

The book, Capote once said, was “rather bitter” and “real,” but the film was “a mawkish valentine to New York City and Holly and, as a result, was thin and pretty, whereas it should have been rich and ugly. It bore as much resemblance to my work as the Rockettes do to [the Russian ballerina Galina] Ulanova.”

The Manchester Guardian wrote of the book in November 1958:

Mr Truman Capote, cuter and flossier than ever, is back with four brilliant sentimentalities, of which the title story looms larges. It is a neon fairytale. The narrator, an elegant puss – half marzipan, half bourbon – flings the epithets about like confetti and it all goes with a crackle. The Gretal to his sexless Hansel is an ex-child bride from Texas, a schizophrenic heartbreaker of eighteen whose love affairs are fireflies leading through the swamps of New York.

Holly Golightly seems as tough as a baby’s dummy spangled with diamonds, but her heart is all soft, innocent gold.

CLASSIC HOLLYWOOD WEB FEATURE. British actress Audrey Hepburn strums a guitar with her co star George Peppard between takes on the set of “Breakfast in Tiffany’s” at a film studio in Hollywood on Dec. 7, 1960.

Blake Edwards was said to have actually fallen to his knees to beg the film’s producers not to cast George Peppard in the male lead. Hepburn was annoyed that Peppard overanalysed everything and found him rather “pompous.” Mrs. Patricia Neal later said that he thought he wanted to be an “old-time movie hunk,” and didn’t think her character should be so domineering of him.

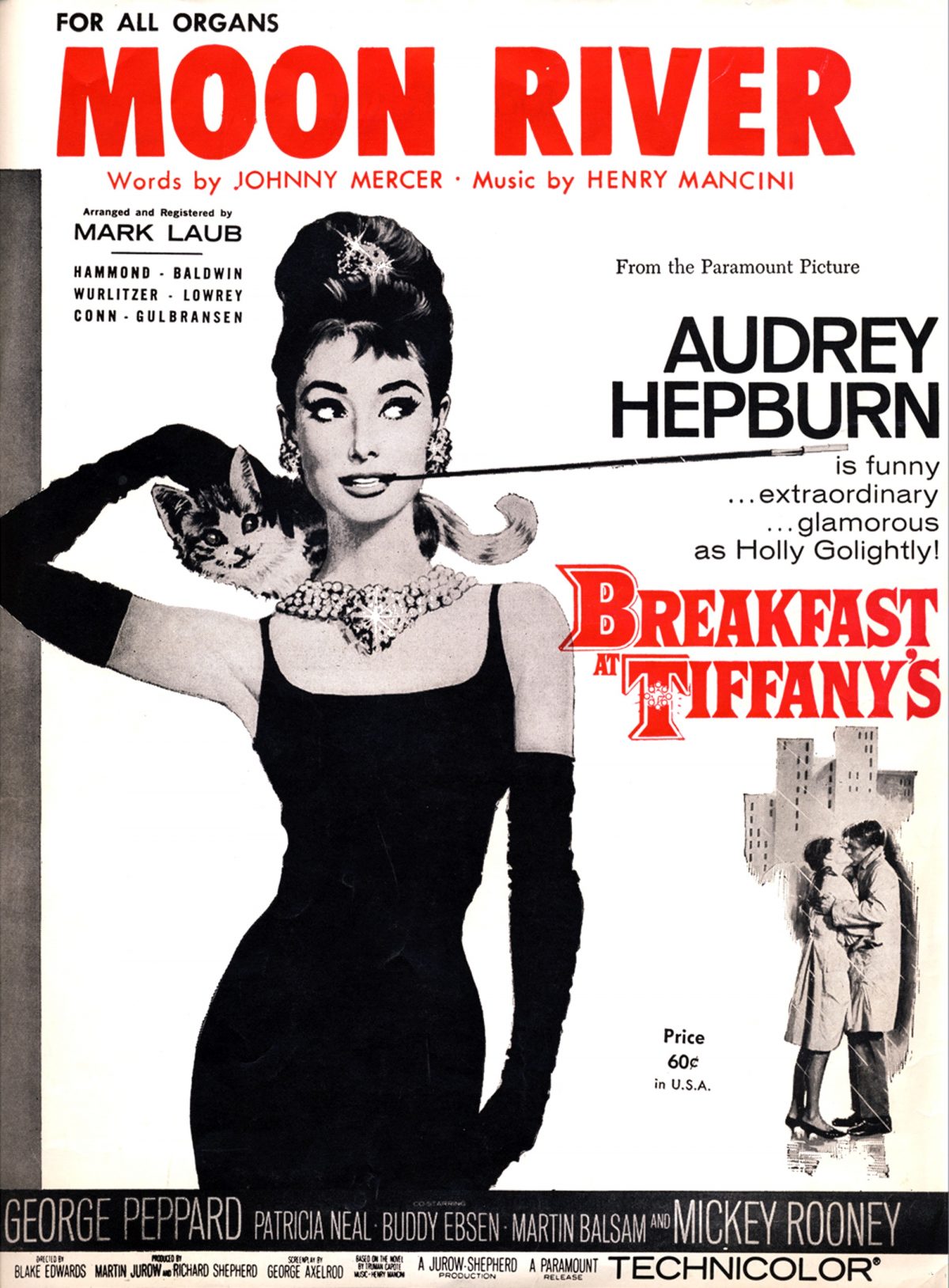

Audrey Hepburn wrote to Henry Mancini (who took a month to write the tune for Moon River and once said that it was the hardest piece of music he ever had to write) when she first saw the film with his music:

Dear Henry,

I have just seen our picture – BREAKFAST AT TIFFANY’S – this time with your score.

A movie without music is a little bit like an aeroplane without fuel. However beautifully the job is done, we are still on the ground and in a world of reality. Your music has lifted us all up and sent us soaring. Everything we cannot say with words or show with action you have expressed for us. You have done this with so much imagination, fun and beauty.

You are the hippest of cats – and the most sensitive of composers!

Thank you, dear Hank.

Lots of love

Audrey

It is said that the producers initially disliked the song but it went on to win Best Original Song at the Academy Awards that year.

The party scene took six days to film. According to studio notes, the partiers drank dozens of real bottles of champagne, as well as gallons of soft drinks, lots of party food (hot dogs, cold cuts, chips, dips, and sandwiches), and 60 cartons of cigarettes. The smoke from which needed to be added to by a smoke machine.

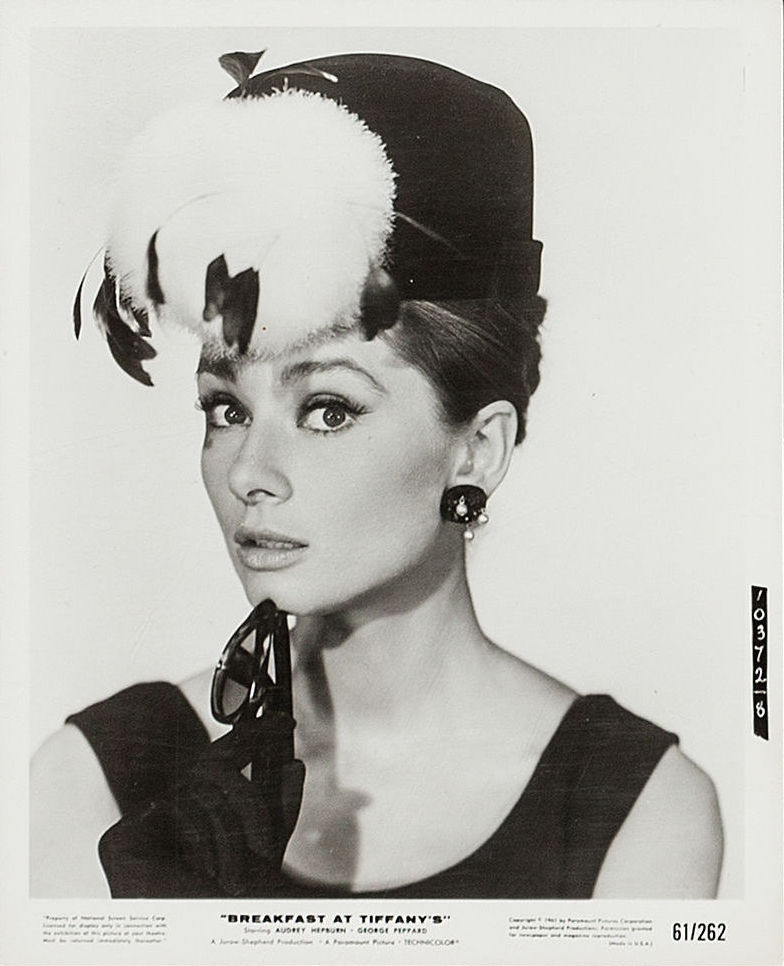

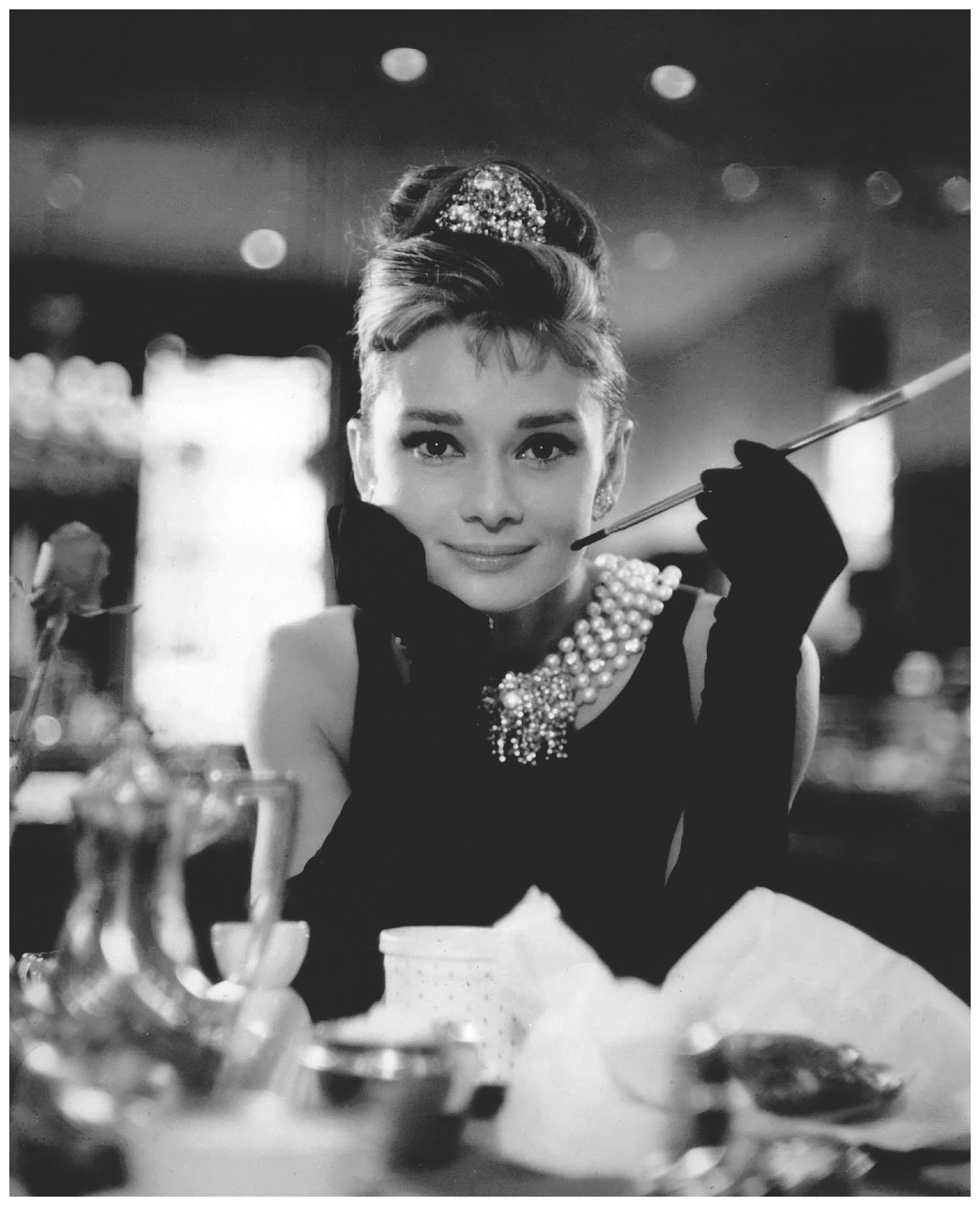

Hubert de Givenchy designed Holly’s famous little black dress – some say it was the first. It was auctioned off in 2006 at Christie’s for over $900,000.

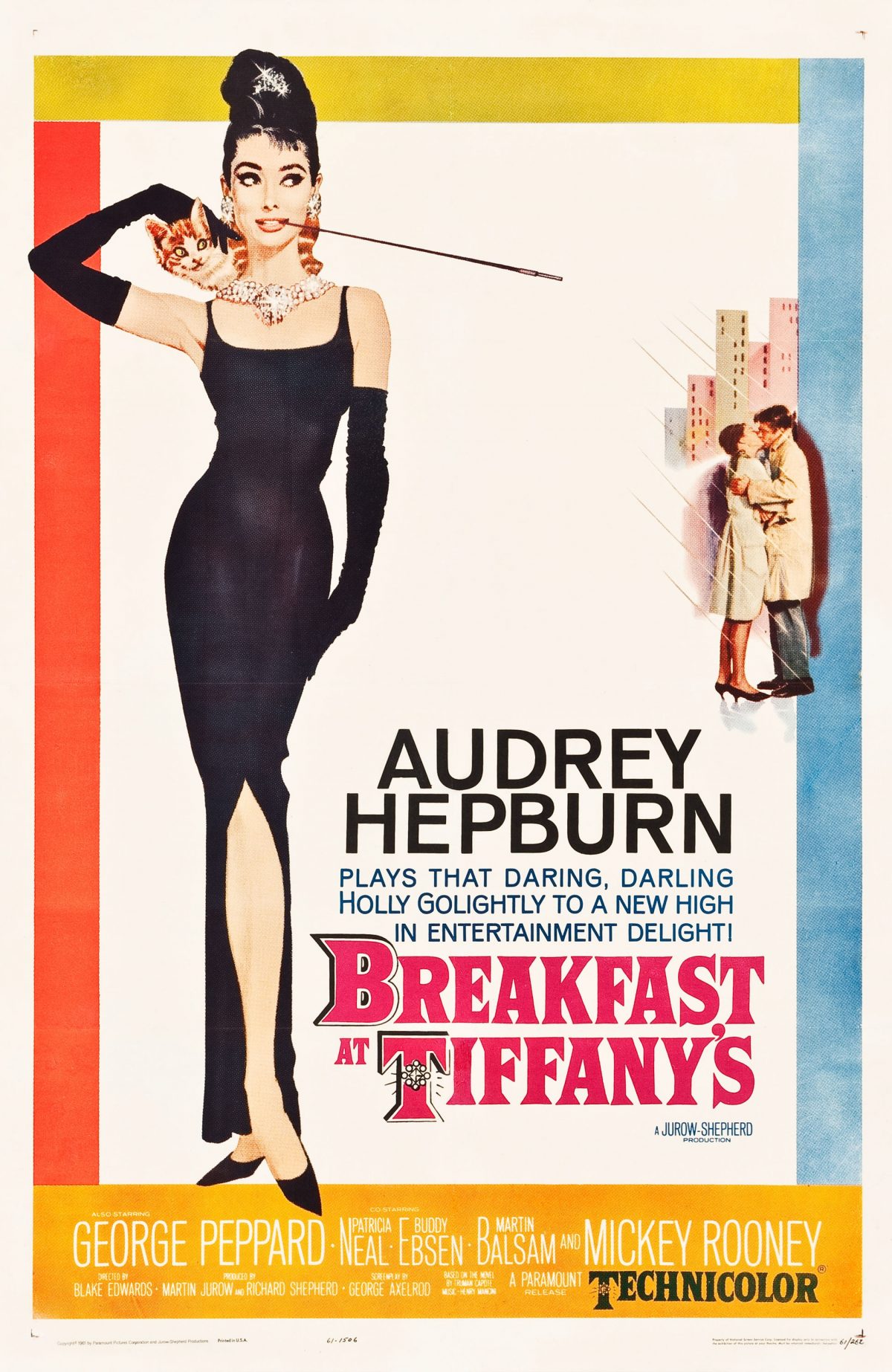

Robert McGinnis designed the poster: “They sent me a few movie stills to work with… The stills weren’t really any good, so I had to take a few leaps of my own. I was shooting pictures of a model for a book cover I was doing, and had her pose with the little orange cat I had back in those days. I put the cat on her shoulder, but the cat wouldn’t stay, so she had to put her right arm up to hold it there. That was an accident. I didn’t tell the model to put her hand there. It was just the only way she could keep the cat in place. That right there was the missing piece, and it was the only variation from the many movie stills they gave me.”

Breakfast at Tiffany’s (1961)

Directed by: Blake Edwards

Cast: Audrey Hepburn, George Peppard, Patricia Neal, Mickey Rooney

Belgian-born actress Audrey Hepburn (1929 – 1993), in a black, shoulderless dress, matching gloves, and a tiara, smiles with a cigarette holder in her hand, in her role as Holly Golightly the film, ‘Breakfast at Tiffany’s,’ directed by Blake Edwards, New York, New York, 1961. (Photo by Paramount Pictures/Courtesy of Getty Images)

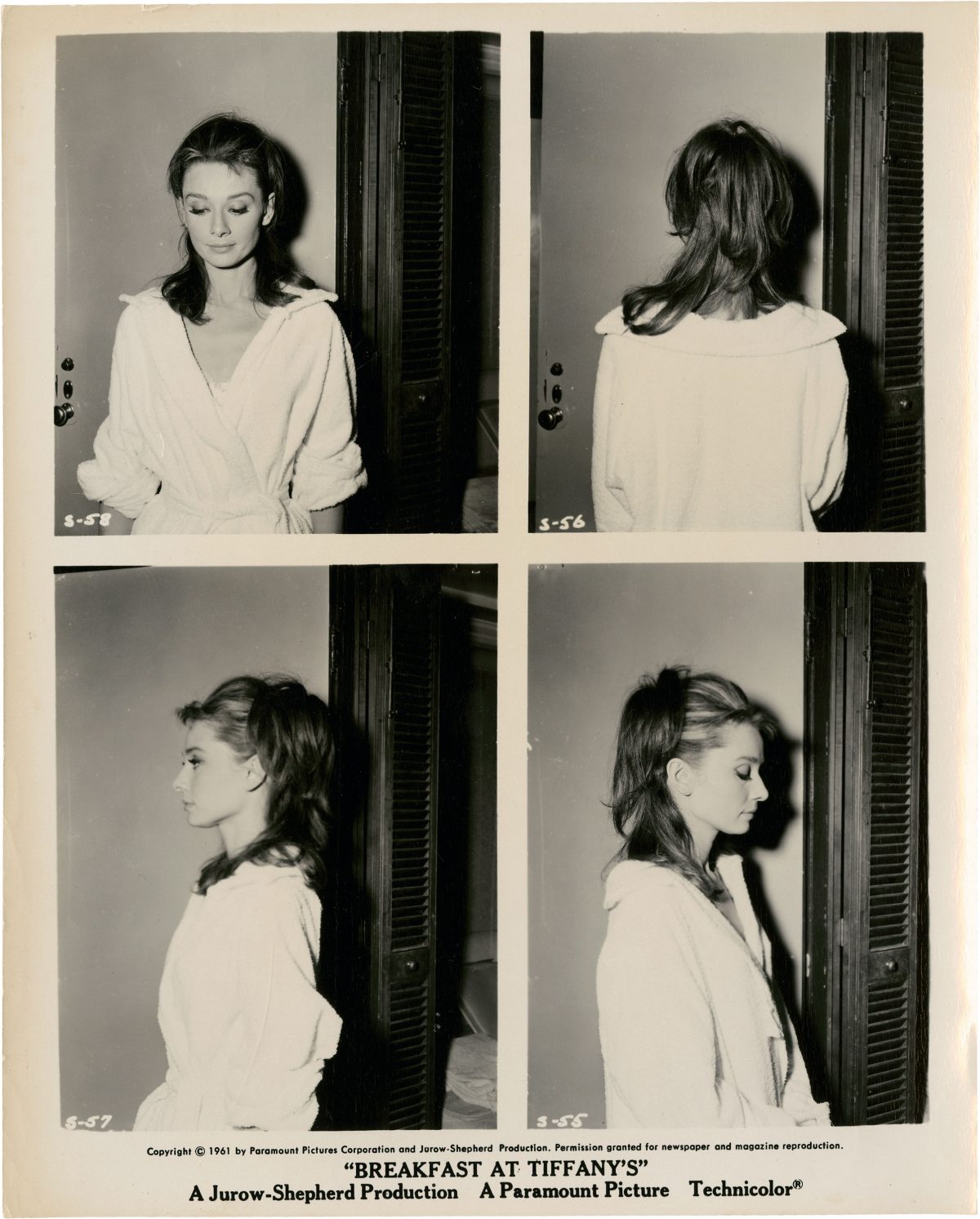

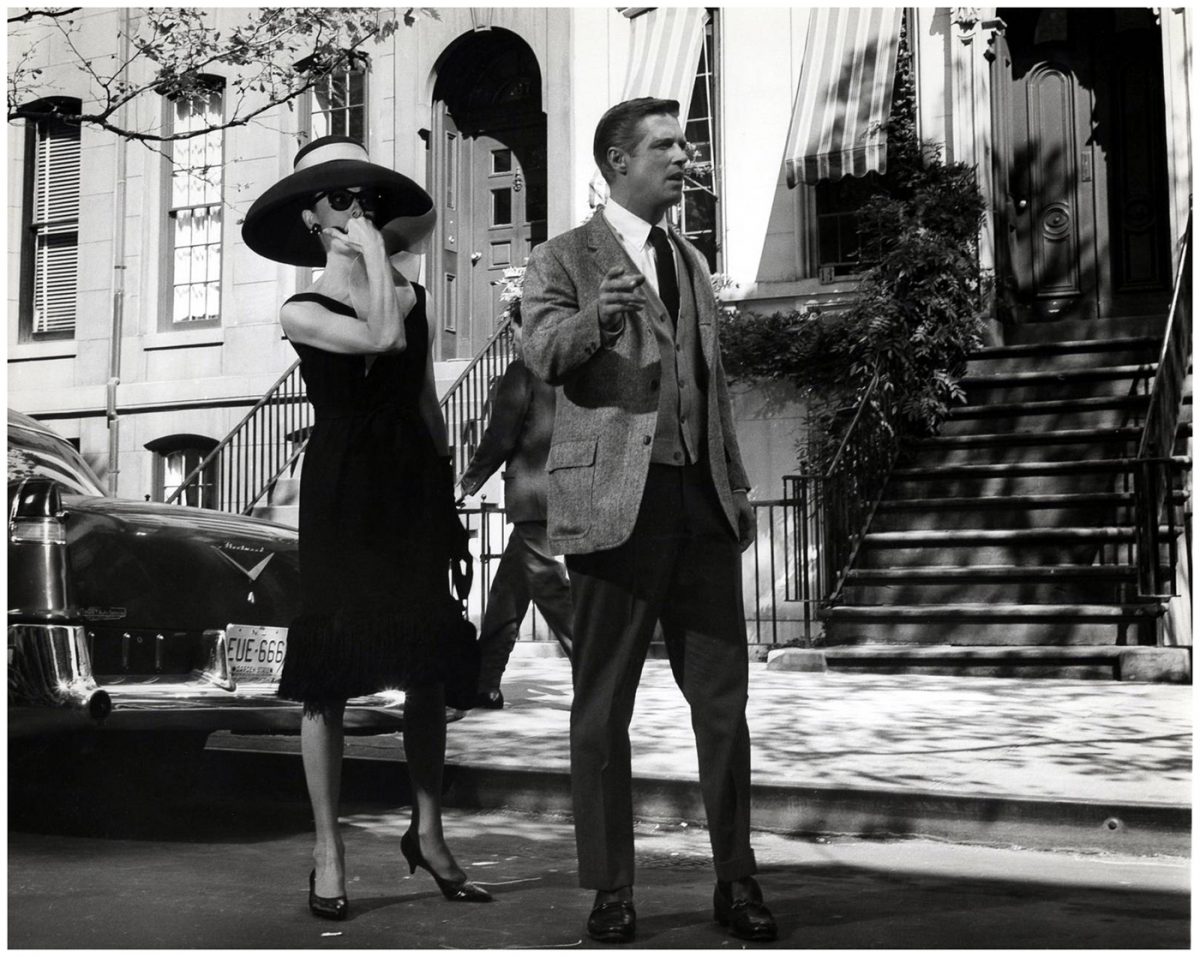

Breakfast at Tiffany’s (1961)

Directed by: Blake Edwards

Cast: Audrey Hepburn, George Peppard, Patricia Neal, Mickey Rooney

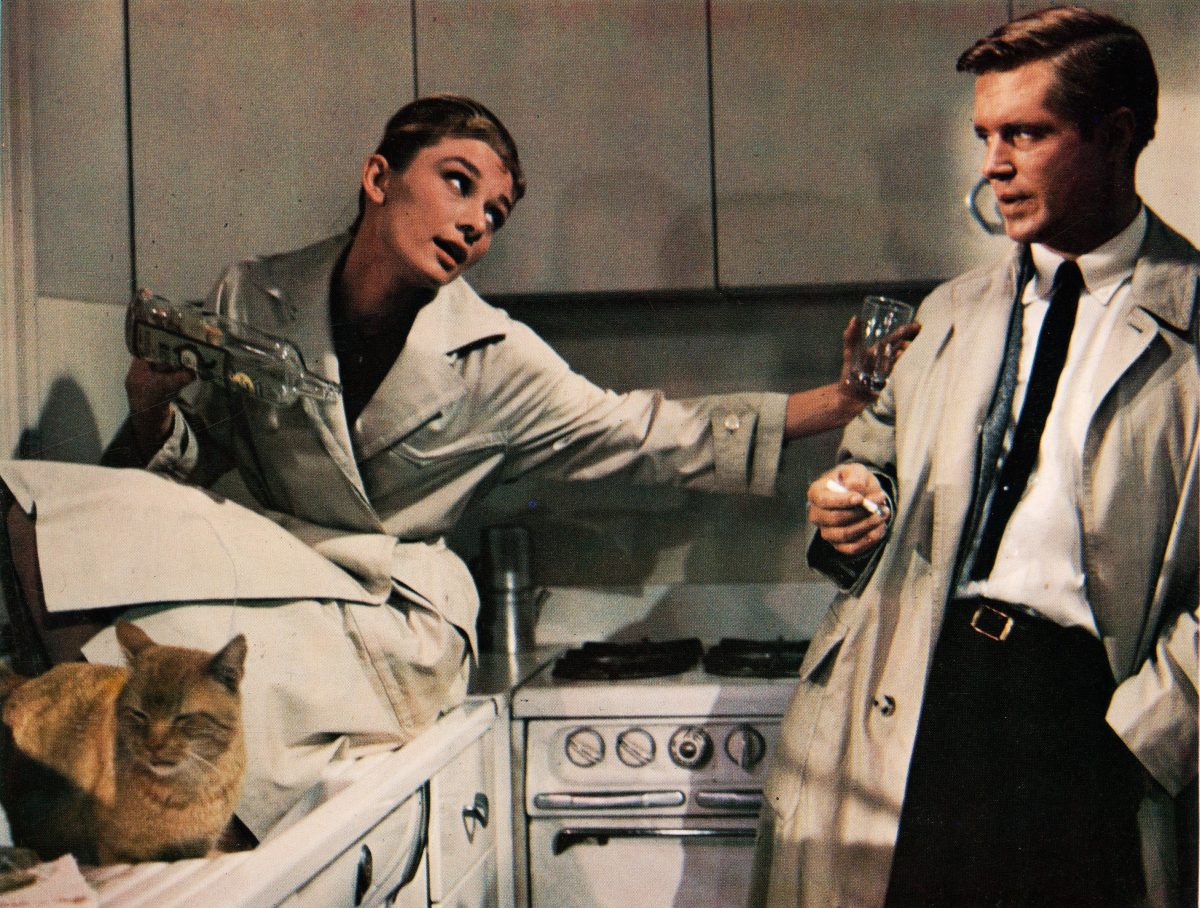

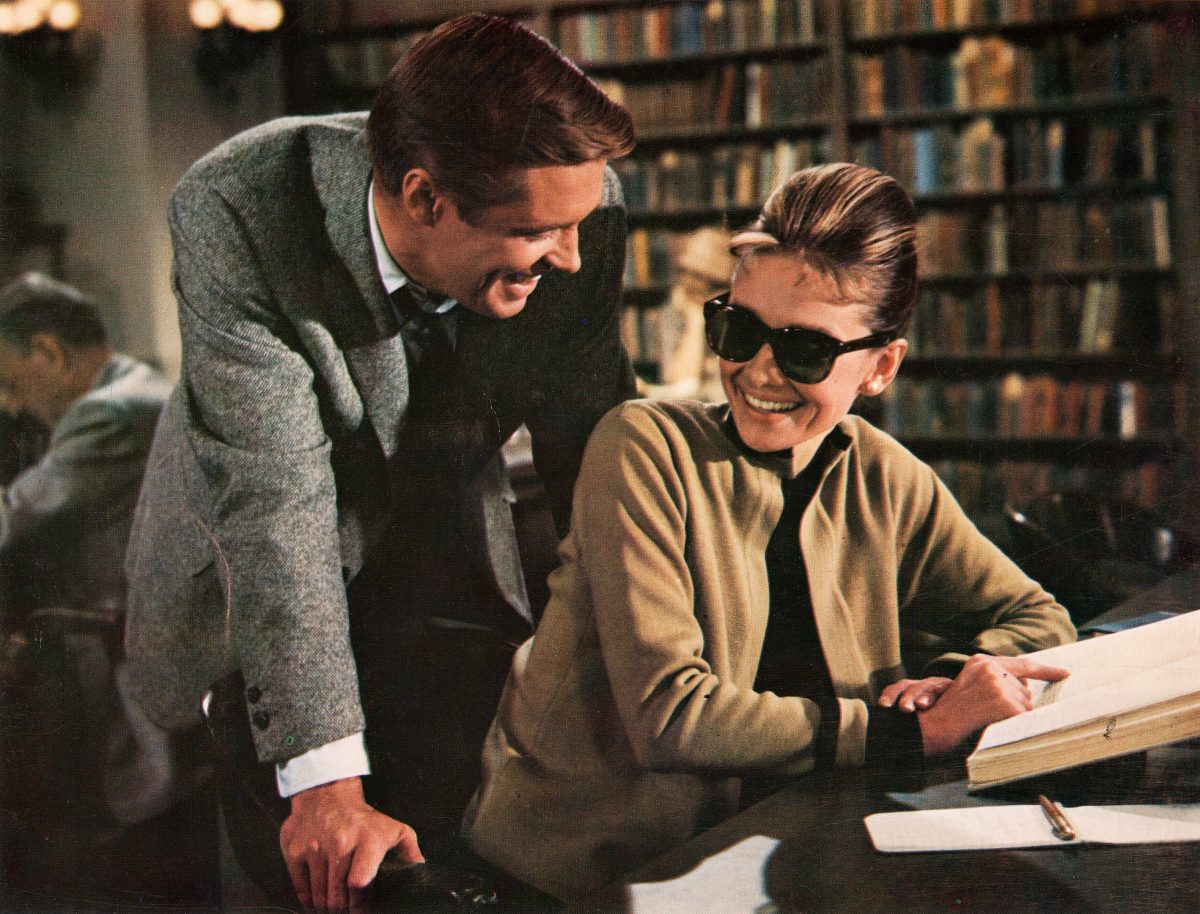

Breakfast at Tiffany’s (1961)

Directed by: Blake Edwards

Cast: Audrey Hepburn, George Peppard, Patricia Neal, Mickey Rooney

* Sarah Churchwell’s article in the Guardian discusses Marilyn Monroe and Audrey Hepburn’s relative suitability for the role of Holly Golightly.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.