Thrown into solitude… [the prisoner] reflects. Placed alone, in view of his crime, he learns to hate it; and if his soul be not yet surfeited with crime, and thus have lost all taste for any thing better, it is in solitude, where remorse will come to assail him…. Can there be a combination more powerful for reformation than that of a prison which hands over the prisoner to all the trials of solitude, leads him through reflection to remorse, through religion to hope; makes him industrious by the burden of idleness..” – Alexis de Tocqueville and Gustave de Beaumont’s letter to the French Government (1831) on their visit to Eastern State Penitentiary.

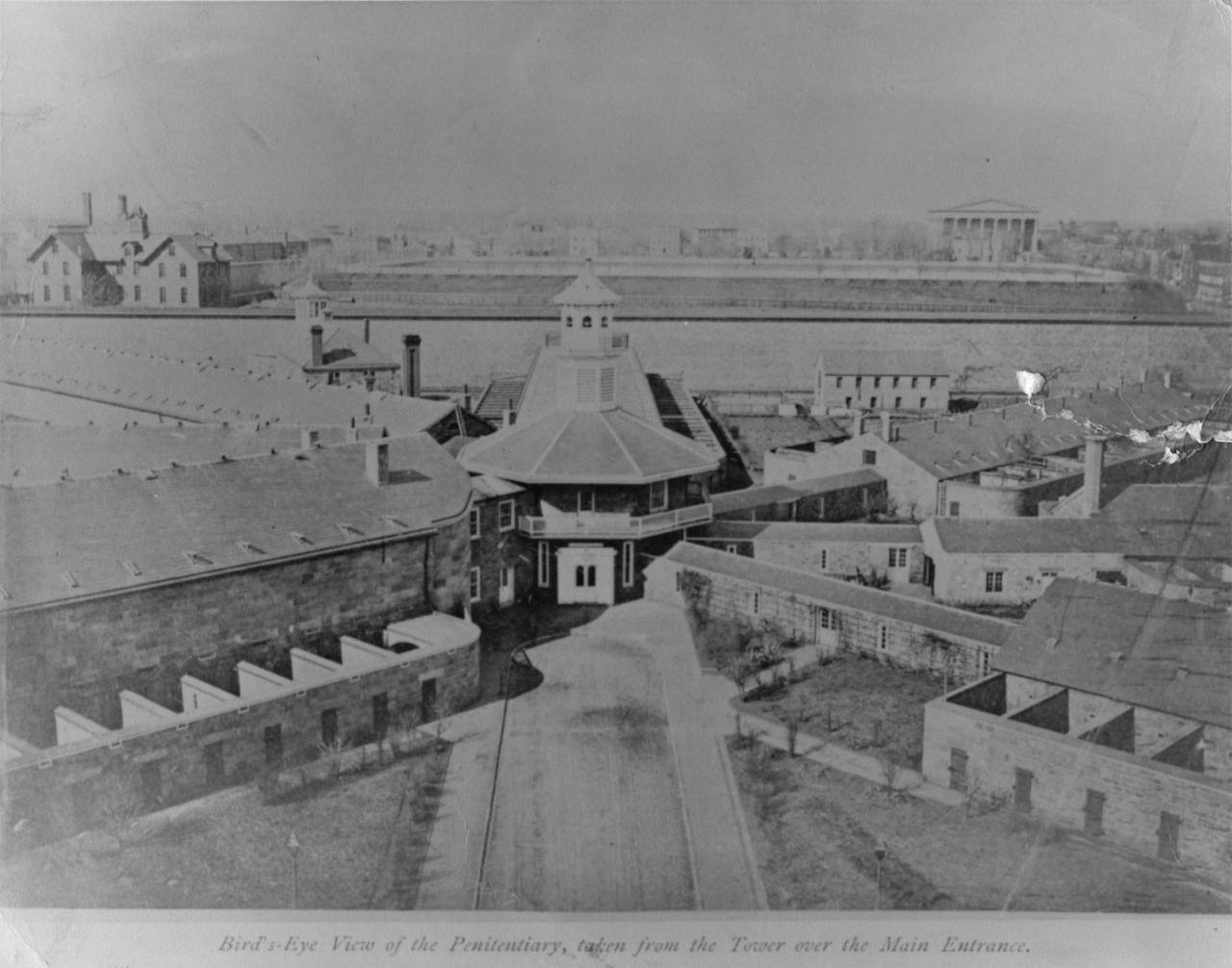

View from the Administration Building, c. 1870. Photo: collection of Eastern State Penitentiary Historic Site, gift of Jack Flynn.

Eastern State Penitentiary has its roots in a 1787 meeting between members of The Philadelphia Society for Alleviating the Miseries of Public Prisons (the world’s first prison reform group was founded in 1787 by Dr. Benjamin Rush) and Benjamin Franklin (January 6, 1705 – April 17, 1790), who joined the group on August 13, 1787. They wanted to improve prison conditions, and use them to encourage prisoners to reflect on their errors and seek Enlightenment. Franklin resolved to build a prison designed to create genuine regret and penitence in the criminal’s heart. The prison would change the behavior of inmates through “confinement in solitude with labor”.

Prison would aid what Auschwitz survivor Viktor Frankl (March 26, 1905–September 2, 1997) called Man’s Search for Meaning. But where Frankl found resolve and solace through humor and love for mankind, the Eastern State Penitentiary prisoner was forced to look for it in the Heavens and a spiritual awakening. Franklin and his fellow campaigners saw no further need for “public punishments” like “the gallows, the pillory, the stocks, the whipping post, and the wheelbarrow”. Their new Penitentiary would offer an enlightened alternative.

Land was earmarked for the new prison on farmland outside Philadelphia. In 1829, the place opened. And in stepped Charles Williams, Prisoner Number One. Like everyone of the 250 prisoners in the new model prison, Williams had his own cell. The records tell us:

“…Charles Williams, Prisoner Number One. Burglar. Light Black Skin. Five feet seven inches tall. Foot: eleven inches. Scar on nose. Scar on Thigh. Broad Mouth. Black eyes. Farmer by trade. Can read. Theft included one twenty-dollar watch, one three-dollar gold seal, one, a gold key. Sentenced to two years confinement with labor. Received by Samuel R. Wood, first Warden, Eastern State Penitentiary….”

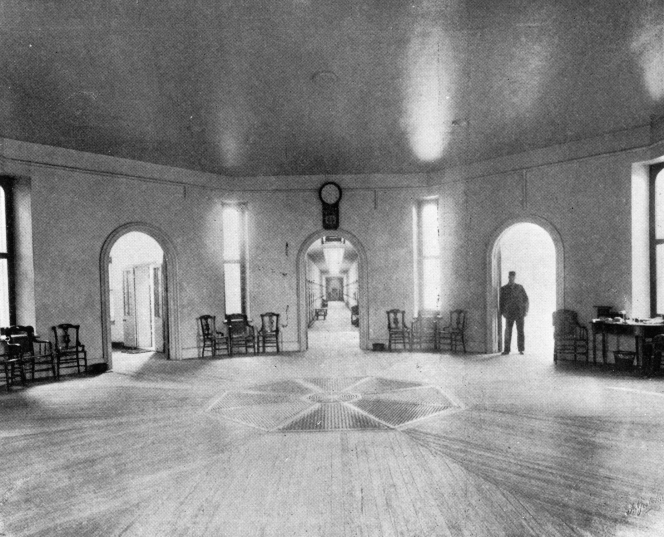

Center. Eastern State Penitentiary Architect John Haviland designed a prison laid out like the hub and spokes of a wheel. The seven cellblocks would radiate from a circular room known as “Center.” He later wrote that it was a design that would promote “watching, convenience, economy and ventilation.” c.1890s.

The concept plan, by the British-born architect John Haviland (1792-1852), reveals the purity of the vision.

Seven cellblocks radiate from a central surveillance rotunda. Haviland’s ambitious mechanical innovations placed each prisoner had his or her own private cell, centrally heated, with running water, a flush toilet, and a skylight. Adjacent to the cell was a private outdoor exercise yard contained by a ten-foot wall. This was in an age when the White House, with its new occupant Andrew Jackson, had no running water and was heated with coal-burning stoves.

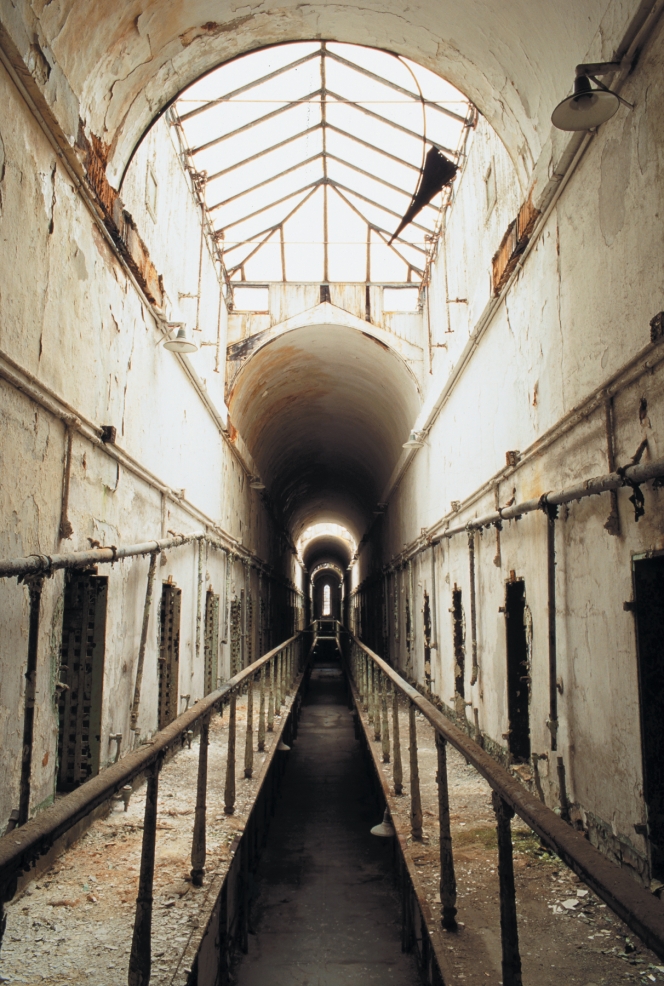

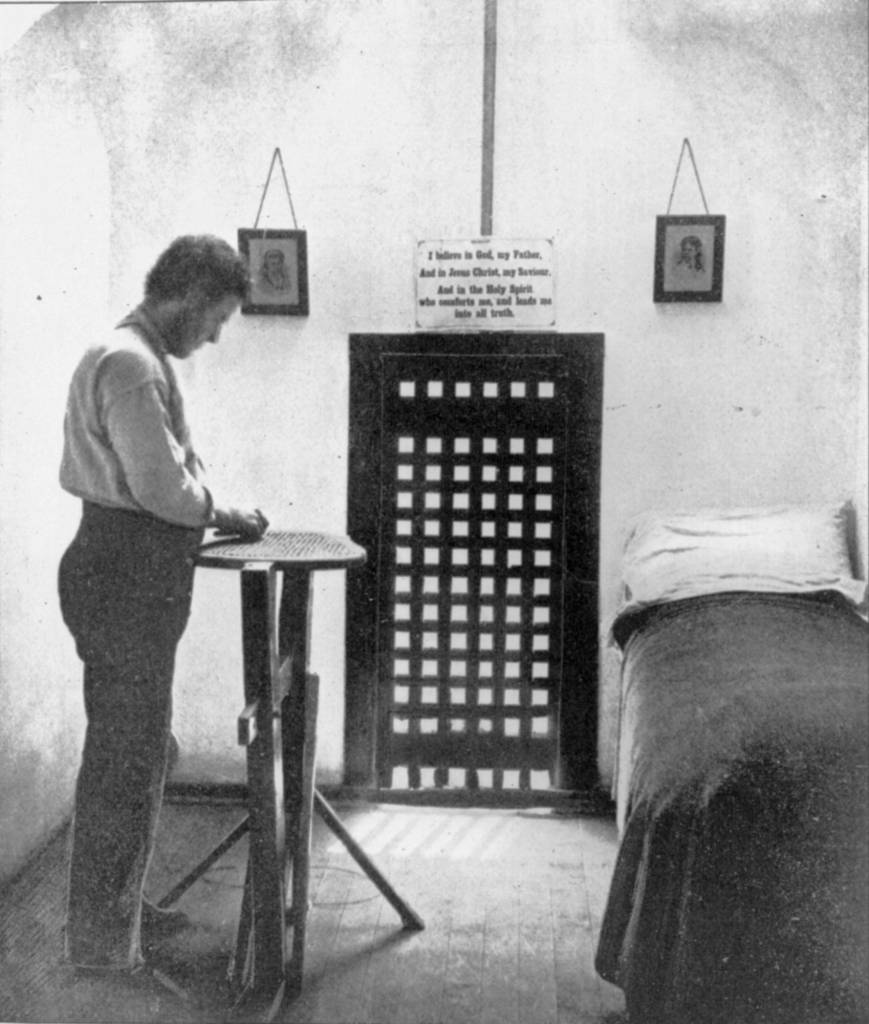

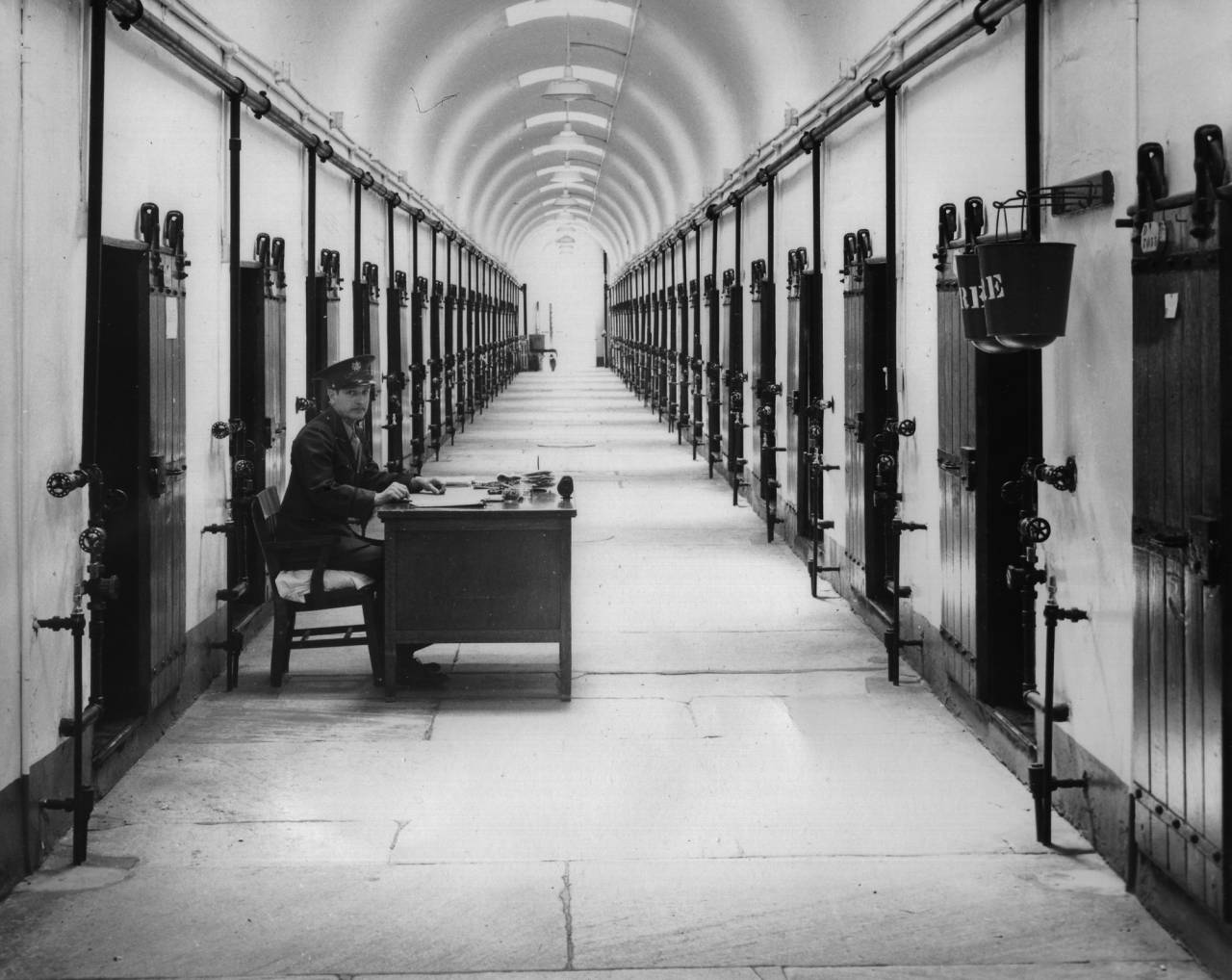

In the vaulted, skylit cell, the prisoner had only the light from heaven, the word of God (the Bible) and honest work (shoemaking, weaving, and the like) to lead to penitence. In striking contrast to the Gothic exterior, Haviland used the grand architectural vocabulary of churches on the interior. He employed 30-foot, barrel vaulted hallways, tall arched windows, and skylights throughout. He wrote of the Penitentiary as a forced monastery, a machine for reform. But he added an impressive touch: a menacing, medieval facade, built to intimidate, that ironically implied that physical punishment took place behind those grim walls.

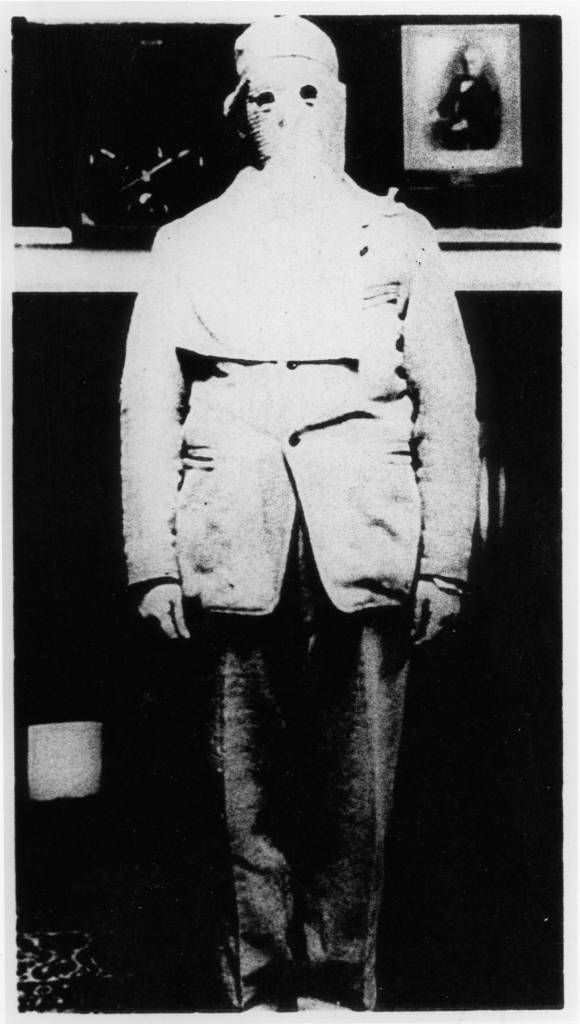

The early system was strict. To prevent distraction, knowledge of the building, and even mild interaction with guards, inmates were hooded whenever they were outside their cells. But the proponents of the system believed strongly that the criminals, exposed, in silence, to thoughts of their behavior and the ugliness of their crimes, would become genuinely penitent. Thus the new word, penitentiary.

Inmates shoemaking, c. 1897. Photo: collection of Eastern State Penitentiary Historic Site, from Warden Cassidy on Prisons and Convicts.

Cellblock 3 corridor, c. 1897. Photo: collection of Eastern State Penitentiary Historic Site, from Warden Cassidy on Prisons and Convicts.

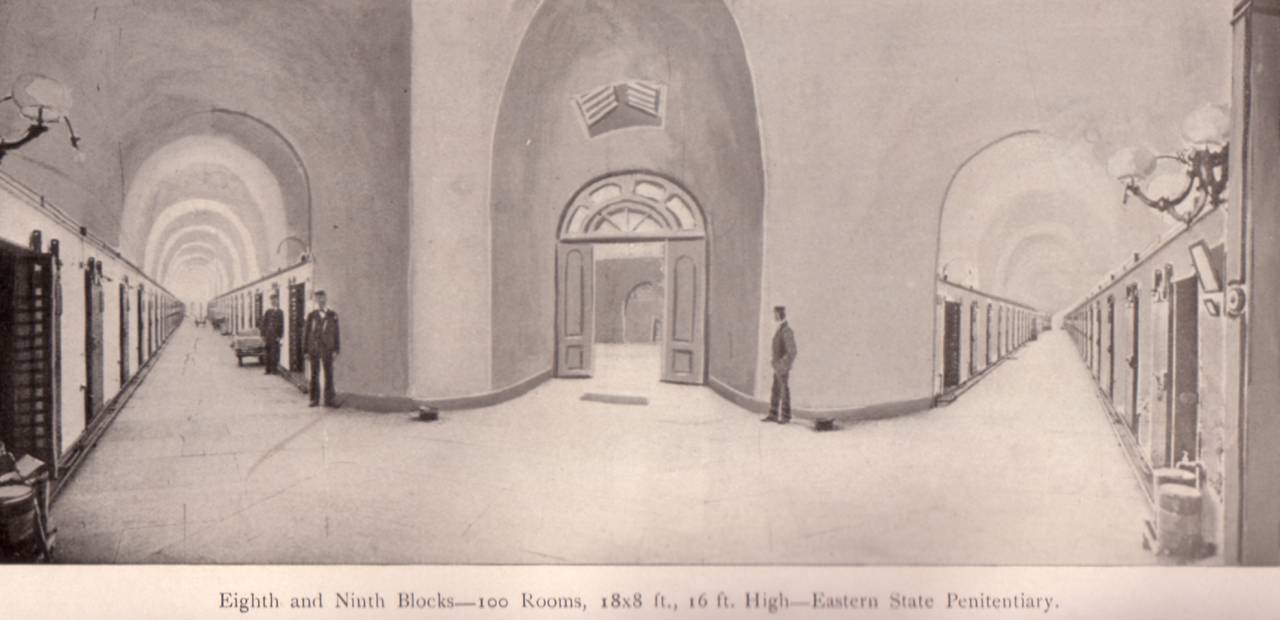

Cellblocks 8 and 9 corridors, c. 1897. Photo: collection of Eastern State Penitentiary Historic Site, from State Prisons, Hospitals, Soldiers’ Homes and Orphan Schools Controlled by the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania.

Cellblock 5 Gallery. When Eastern State Penitentiary opened in 1829, visitors from around the world marveled at its grand architecture and radical philosophy. With its high arched cathedral and over 1,000 skylights, the building feels more like a religious space, rather than a prison.

Not everyone was convinced.

In its intention I am well convinced that it is kind, humane, and meant for reformation; but I am persuaded that those who designed this system of Prison Discipline, and those benevolent gentleman who carry it into execution, do not know what it is that they are doing….I hold this slow and daily tampering with the mysteries of the brain to be immeasurably worse than any torture of the body; and because its ghastly signs and tokens are not so palpable to the eye,… and it extorts few cries that human ears can hear; therefore I the more denounce it, as a secret punishment in which slumbering humanity is not roused up to stay. – Charles Dickens recalls his visit to the prison in 1841 (from American Notes for General Circulation).

All seven original cellblocks could be seen by a single overseer or guard from the Central Rotunda. However, when Cellblocks 8 and 9 were added in 1877, mirrors had to be installed in the hallway to allow guards to see down these new blocks from the center.

The critics eventually prevailed. The Pennsylvania System was abandoned in 1913. In some countries in Europe and Asia the separate system continued until the post-Second World War period.

The later additions into the Eastern State Penitentiary complex illustrate the compromise reached when this munificent, ill-fated intellectual movement collided with the reality of modern prison operation. Warden Michael Cassidy added the first cellblocks in the 1870s and 1890s. They retain the barrel vaults and skylights, the feeding doors and mechanical systems. Mirrors provide continued surveillance into the new cellblocks from the Rotunda. But the cells did not include exercise yards. Inmates were issued hoods with–for the first time–eye holes. They would exercise together, in silence and anonymity.

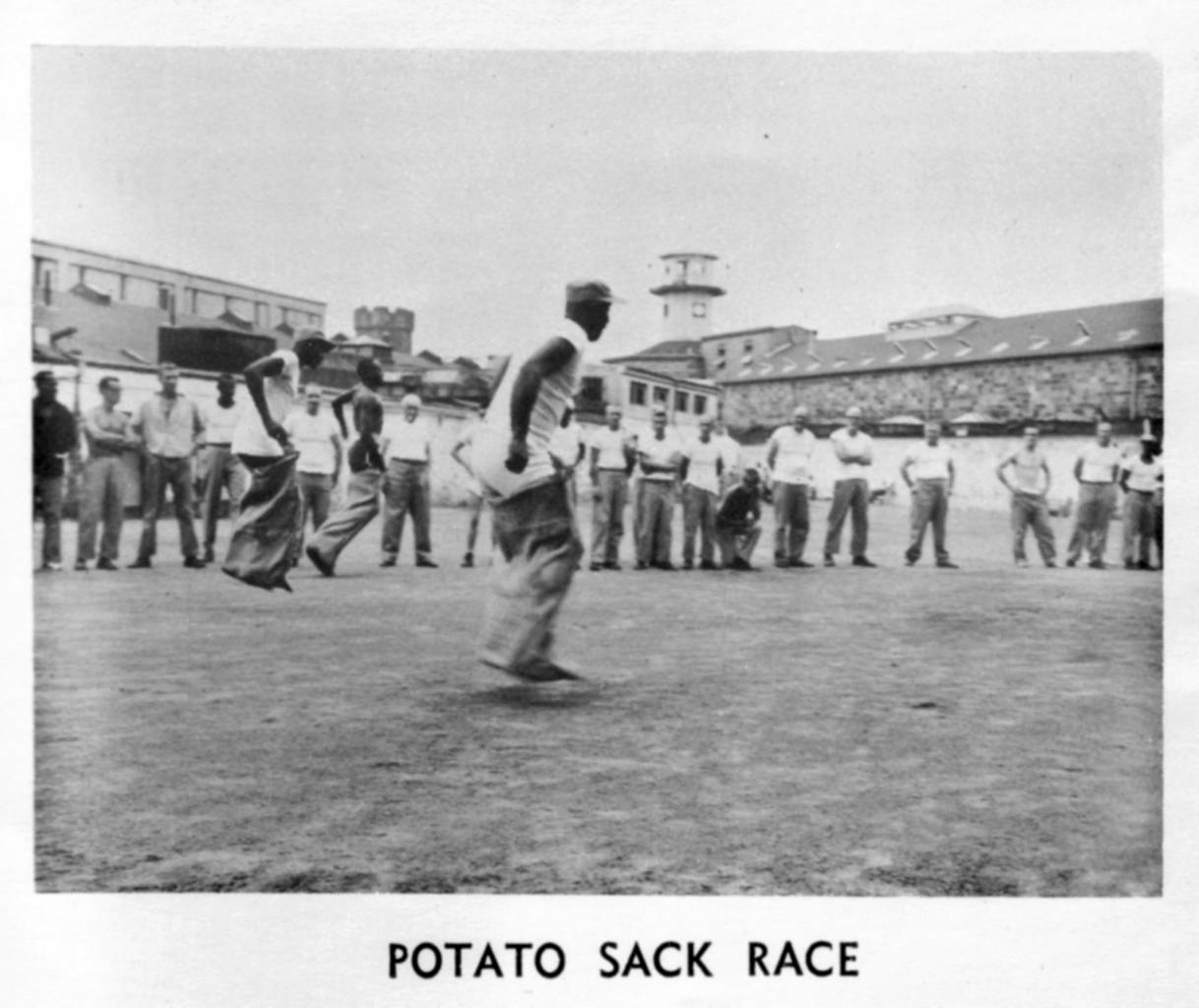

The system of solitary confinement at Eastern State did not so much collapse as erode away over the decades. A congregate workshop was added to the complex in 1905, eight years before the Pennsylvania System was officially discontinued. By 1909 an inmate newspaper, The Umpire, ran a monthly roster of the inter-Penitentiary baseball league scores…

Inmate caning a chair, c. 1870s. Photo: from Richard Vaux, Brief Sketch of the Origin and History of the State Penitentiary (Philadelphia: McLaughlin Brothers, 1872).

Still more cellblocks were constructed. Reinforced concrete replaced stone. The new cells were small, square, and lit by ordinary windows, but the halls had the catwalks and skylights typical of the early Eastern cellblocks. The cellblocks were invisible from the Rotunda. Subterranean and windowless cells, with neither light nor plumbing, brought a return to solitary confinement at Eastern. This time the isolation was not for redemption, but punishment. The cells were nicknamed “Klondike.”

Pep “The Cat-Murdering Dog” was a black Labrador Retriever admitted to Eastern State Penitentiary on August 12, 1924. Prison folklore tells us that Pennsylvania Governor Gifford Pinchot used his executive powers to sentence Pep to Life Without Parole for killing his wife’s cherished cat. Prison records support this story: Pep’s inmate number (C-2559) is skipped in prison intake logs and inmate records. The Governor told a different story. He said Pep had been sent to Eastern to act as a mascot for the prisoners. He and the Warden, Herbert “Hard-Boiled” Smith, were friends. Pep was much loved, and lived among the inmates at Eastern State for about a decade. While the truth may never be known, in photographs Pep—with his head down and ears back–looks GUILTY.

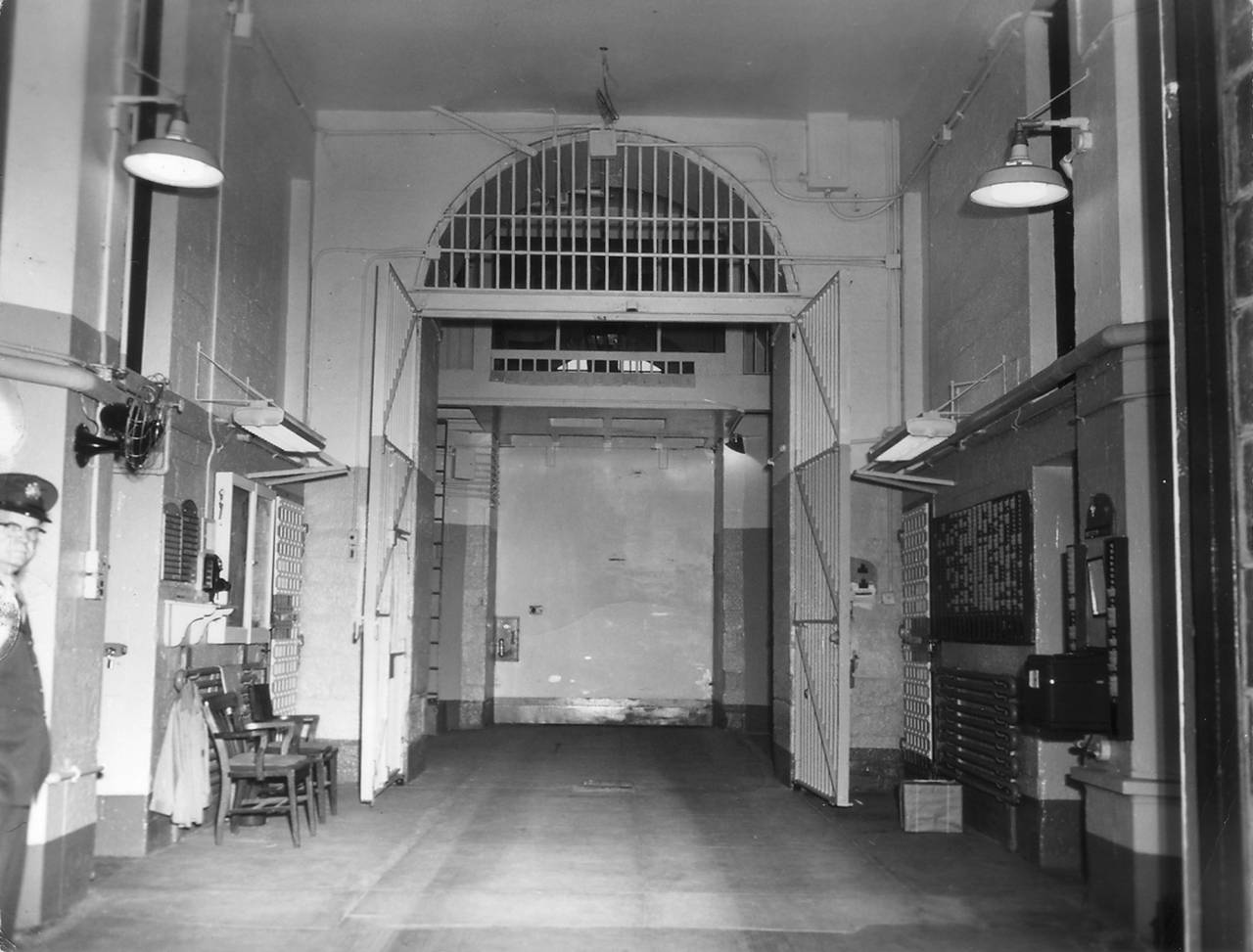

The last major addition was made to Eastern State Penitentiary’s complex of buildings in 1956: Cellblock Fifteen, or Death Row. This modern prison block marked the final abandonment of any aspect of the Eastern’s original architectural vocabulary. The fully-electronic confinement system inside separated the inmates from the guards at virtually all times. Within the Penitentiary’s perimeter wall, built with the belief that all people are capable of redemption, prisoners awaited execution.

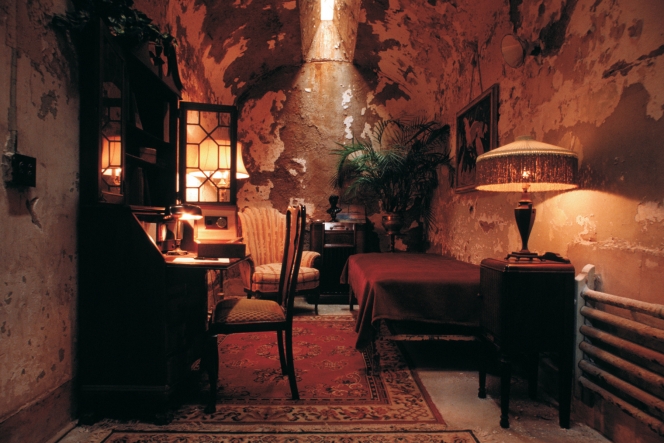

Cell of Al Capone. “Scarface” Al Capone, “the notorious king of Chicago’s racket world,” got his first taste of prison life in Philadelphia. While the courts were tough on Capone, his stay at Eastern State Penitentiary was rather comfortable. Capone spent 8 months in one of Eastern State’s “Park Avenue” cells. In 1929, a newspaper reporter for the Philadelphia Public Ledger described Capone’s cell.

“The whole room was suffused in the glow of a desk lamp which stood on a polished desk… On the once-grim walls of the penal chamber hung tasteful paintings, and the strains of a waltz were being emitted by a powerful cabinet radio receiver of handsome design and fine finish.”

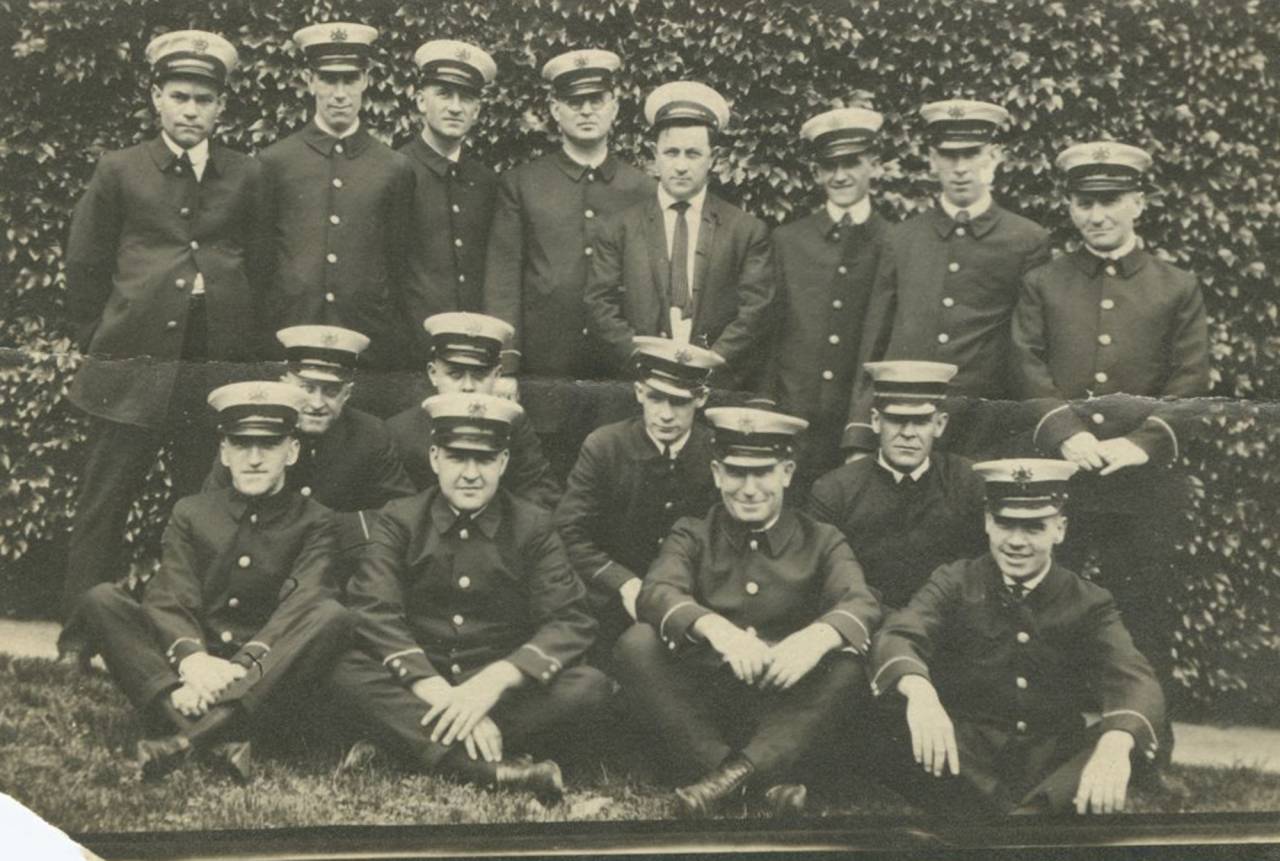

Lieutenant Jack Skelton at desk, c. 1944. Photo: collection of Eastern State Penitentiary, gift in memory of Lieutenant Jack Skelton.

View from the Administration Building, c. 1960. Photo: collection of Eastern State Penitentiary, gift of Alan J. LeFebvre.

Fingerprinting in the Bertillon Office, c. 1960. Photo: collection of Eastern State Penitentiary Historic Site, gift of the Scheerer Family.

Inside of the gatehouse, c. 1960. Photo: collection of Eastern State Penitentiary Historic Site, gift of the Scheerer Family.

Eastern Echo, Winter 1964, “July 4th Field Events.” Collection of Eastern State Penitentiary Historic Site, gift of the William F. Derau Family.

The Commonwealth closed the facility in 1971.

The United States now has the highest rate of incarceration in the world, by far, with 2.2 million citizens in prison or jail. This phenomenon has generally been driven by changes in laws, policing, and sentencing, not by changes in behavior. The results have disproportionately impacted poor and disenfranchised communities (mostly communities of color). In contrast, these historic changes remain nearly invisible to many Americans.

Pictures via Eastern State, which you can visit. More information here.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.