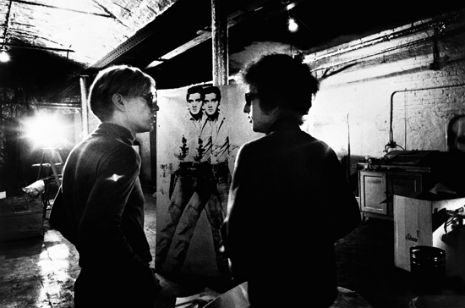

In 1965 Andy Warhol made a short black-and-white film of Bob Dylan. Recording on a Bolex 16mm camera and 100-feet rolls of film, Warhol and his assistant Gerard Malanga collected Dylan for their moving visitor books. In all, Warhol made 472 3-minute films of 189 callers to his Factory studio on New York’s East 47th Street.

Edie Sedgwick, Salvador Dali, Nico, Marcel Duchamp, Mama Cass, Allen Ginsberg, Dennis Hopper, Lou Reed and Susan Sontag all posed for Warhol. But not every sitter was a famous face. One film is captioned by Callie Angel in Andy Warhol Screen Tests: The Films of Andy Warhol Catalogue Raisonne: “A young man named Stevie, with an illegible last name. Near the end of the roll, someone throws water on his face from offscreen.”

In its review of Angel’s book, the University of Minnesota Press (UMP) writes:

Between 1964 and 1966, Warhol created more than four hundred black-and-white moving image portraits or “Screen Tests” of luminaries, celebrities, and wannabes from the art, literary, music, dance, film, and modeling worlds. Originally dubbed “stillies” by Warhol for their subjects’ uncanny lack of movement in a moving picture medium, these approximately three-minute, 16mm silent films were first inspired by Warhol’s discovery of a New York Police Department brochure that contained mug shots of the Thirteen Most Wanted criminals.

Ever anxious to eroticize the illicit, Warhol derived an idea for a series of portrait films called the Thirteen Most Beautiful Boys, which would combine the artist’s obsession with collection and classification with his emerging fascination with duration. Over the course of two years, far more than thirteen portraits were made, and not solely of boys. In the catalogue,

“None of these screen tests amounted to giving those people the opportunity to go on in the underground film world,” said Malanga in 2009. “It was kind of a parody of Hollywood.”

The face sat. The camera rolled. J. Hoberman writes: “Warhol documented his subjects simply having what a Hindu might call their being – that is, coping with the odd circumstance of total, indifferent scrutiny.”

You can pose and gurn for a few seconds. But after a minute or so something is going to change. Warhol wanted to see behind the mask.

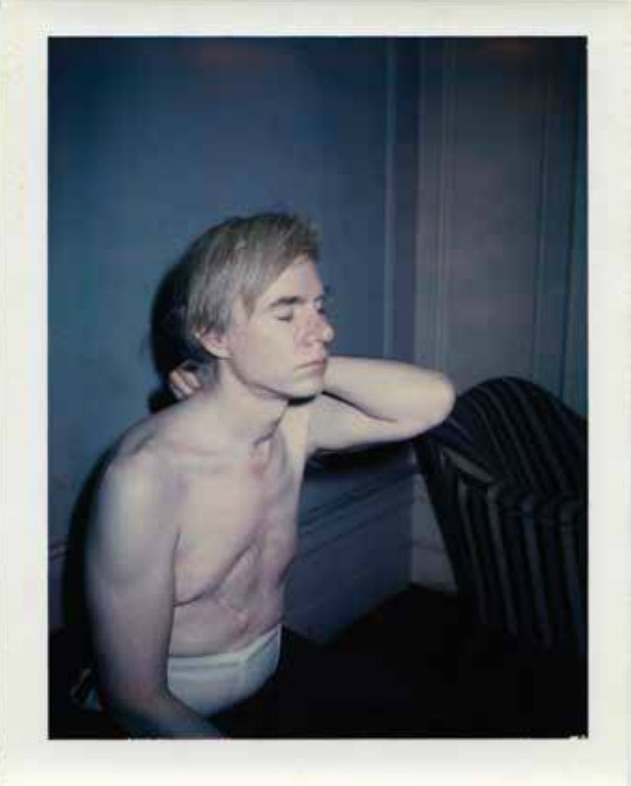

Andy Warhol notes in The Philosophy of Andy Warhol:

“Beauties in photographs are different from beauties in person. It must be hard to be a model, because you’d want to be like the photograph of you, and you can’t ever look that way. And so you start to copy the photograph. Photographs usually bring in another half-dimension. (Movies bring in another whole dimension. That screen magnetism is something secret – if you could only figure out what it is and how to make it, you’d have a really good product to sell. But you can’t even tell if someone has it until you actually see them up there on the screen. You have to give screen tests to find out.)”

UMP:

By 1966, these films came to be known as “screen tests” in spite of the fact that they were not used to determine the subject’s desirability for future film projects. Being asked to

pose for Warhol’s camera often flattered visitors to the Factory with the lure of fame and glamour, as well as the possibility of screen immortality, but submitting to Warhol’s sadomasochistic rules tended toward the unbearable. In addition to mandating the conventions that applied to official portraits like passport photos—the camera should not move, the background should be as plain as possible, and the subject should be well lit and centered—Warhol added a few requirements that were nearly unthinkable in a moving picture format. Before walking away from his Bolex camera and allowing the subject to endure the camera’s intractable gaze, Warhol instructed his sitters to refrain from any kind of movement whatsoever, including talking, smiling, and even blinking.

American folk/rock singer and songwriter Bob Dylan smiles during a meeting with the British press, April 28, 1965.

“In Pop: The Genius of Andy Warhol, Tony Scherman and David Dalton write:

When movies were invented, their critics claimed there was one thing they couldn’t do: capture the soul, the distillation of personality. Ironically, this turned out to be one of film’s greatest capacities. Operated close up, the movie camera lets us read, perhaps more clearly than any other instrument, a subject’s emotions. As his hundreds of sixties, seventies, and eighties photo-silk-screen portraits attest, Warhol was compelled to portray the human face. The Bolex let him home in on flickering expressions and shifting nods, a near-instant raising and lowering of eyebrows, a quick sidelong glance, pensive and thoughtful slow noods, or a three-minute slide from composure into self-conscious giddiness–fleeting emotions that neither paint nor a still camera could capture. Andy’s ambition for the Screen Tests, as for film in general, was to register personality…

As for Andy’s motives, he was clearly star-struck, in awe of Dylan’s sudden, vast celebrity. He had a more practical agenda, too: to get Dylan to appear in a Warhol movie.

Craig Hubert says the two men had not formerly met before the day of the screen test:

The two cornerstones of 1960s popular culture had never officially met, but by various accounts Warhol was star struck by the singer, who was just exiting his troubadour phase and entering his sunglasses-and-wild-hair electric period. Dylan and Warhol had already undoubtedly crossed paths in New York: Warhol, in his memoir, remembers stepping over Dylan, drunk and having fun, while leaving a party on Macdougal Street a few years earlier, and other reports claim Dylan and Warhol were often at the same parties. The two were definitely aware of each other, despite claims to the contrary, and their two camps, described by Victor Brockis in his biography of Warhol as “the two poles of the New York underground,” remained in opposition to each other long after the meeting.

The meeting was far from relaxed.

“Every time they put a Bob Dylan record on, we’d take it off and put on Maria Calls,” Ondine, a former Warhol superstar tells Steven Watson in Factory Made: Warhol and the Sixties. “And [Dylan] sat there, and he sat in his chair quietly and got more and more pissed off.”

Richard Metzger adds:

When Dylan stopped by the tin-foil covered Factory, he is alleged to have taken an immediate dislike to Warhol and the “phonies” of his entourage. It has long been suspected that the spitting lyrics of “Like a Rolling Stone,” in part, describe Dylan’s feelings about Warhol—was he “the diplomat on the chrome horse”?—and how he felt about the artist’s perceived exploitation of Edie Sedgwick, who Dylan was at one point romantically involved with (and who was his muse for some of Blonde on Blonde).

John Herald has a witty aside with a biter aftertaste of how the shoot ended:

Dylan visited Warhol’s Factory studio in mid to late December 1965. After sitting for his two-minute “screen test,” Dylan was given a tour of the studio by Warhol himself. At some point, he asked for payment for doing the film and brazenly picked out a Double Elvis as his booty (the stories on how this transpired vary). Warhol didn’t really know what to say, so off trooped Dylan and his entourage, carrying the silk-screen which they roped to the top of Dylan’s station wagon. When Dylan got back to his new home in Woodstock, he expressed dislike for the portrait and traded it for a sofa from his manager’s wife Sally Grossman (the woman on the cover of the album Bringing It All Back Home). In 1988, Sally sold the Double Elvis for $720,000. Two-and-a-half decades later, in November 2014, a Triple Elvis sold for $81.9 million. In his memoir Chronicles, Dylan expressed some regrets over the deal he made for the sofa.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.