You and Brion have described your collaborations over the years as the products of a “third mind.” What’s the source of this concept?

WILIAM S. BURROUGHS: A book called Think and Grow Rich.

BRION GYSIN: It says that when you put two minds together. . .

BURROUGHS: . . . there is always a third mind . . .

GYSIN : . . . a third and superior mind . . .

BURROUGHS: . . . as an unseen collaborator.

Bryon Gysin, William Burroughs and the Dream Machine, 1972, by Charles Gatewood

William S. Burroughs’ cut ups are arguably the most famous and productive literary experiment of the 20th century, rippling through the work of hundreds of novelists, artists, and musicians who followed in his wake. It’s hard to overstate Burroughs’ importance to the counterculture and, thus, to popular culture writ large. But Burroughs himself was always quick to note that he wouldn’t have discovered his metier without his longtime friend and collaborator Brion Gysin, the artist Burroughs called the only man he ever respected.

Brion Gysin with the Dream Machine, 1962

It was Gysin who invented cut-ups, in his sound and film experiments with mathematician Ian Sommerville, using techniques Burroughs would later take up in his own occult experiments. In 1978 Gysin and Burroughs extolled the virtues of the cut-up method in their book The Third Mind. Burroughs found the cut-up method transformative, “an efficient tool capable of dismantling all the mechanisms of fiction,” writes art historian Gerard-Georges Lemaire. But Gysin had “already moved on” according to New Museum curator Laura Hoptman.

There is a series of letters [Burroughs] wrote to Gysin in 1960 or 1961 from Tangiers. I mean they wrote daily – there are hundreds of these letters – and they would say things like: ‘Go outside and do a dérivé; walk around and find all the blue objects and take pictures of them and cut them up,’ or, ‘Take your permutation poems and translate them into different languages and then cut them up’. And Gysin would write back: ‘You know, man, this cut-up thing is just not my bag, but this DREAMACHINE!

For Gysin, it was the Dream Machine, which he and Sommerville invented in the early 60s, that pointed the way to the future of art, culture, and entertainment. “A pioneering piece of hallucinatory kinetic art,” writes Visual Melt, the machine was “constructed out of nothing more than a turntable that rotated at 78rpm, a cantilevered light and a cylinder with rounded parallelograms cut from its surface.” Gysin had the idea while falling asleep on a bus.

As the sun set amongst the trees, it created a flicker effect that induced a lucid dream. Later, with Sommerville, he would learn that the revolutions of the turntable could recreate this effect and correspond to the frequency of alpha waves emitted by the brain during deep sleep. It was dubbed as the first piece of art meant to be viewed with eyes closed, and was Gysin’s (unsuccessful) intention to sell the machine to Panasonic in order to eventually replace the television.

Sommerville and Gysin theorized that the 78rpm speed of the Dream Machine “projects light at a constant frequency of eight to thirteen minutes per second,” Marina Cashdan writes at The White Review, “which corresponds to alpha waves present in the human brain during wakeful relaxation. The flickering light creates a trance-like hallucinatory state. For Gysin, the Dream Machine was the culmination of his research.” Debuting in 1962 at the Museé des Arts Decoratifs in Paris, the machine “did in fact prove to be a source of artistic inspiration, though not to the degree Gysin hoped.”

Not only did Gysin believe the Dream Machine could replace television, but he also thought it might replace drugs. He was greatly inspired by Marcel Duchamp, who had tried to market a similar device, the Rotorelief, as a novelty tool for hypnosis and relaxation. Duchamp had failed to arouse interest among investors and the general public. The Dream Machine was also too esoteric for mass appeal. Gysin may have had his eye on the popular market, but the machine arose from a constellation of early sixties experiments with Sommerville and Burroughs that were anything but commercial.

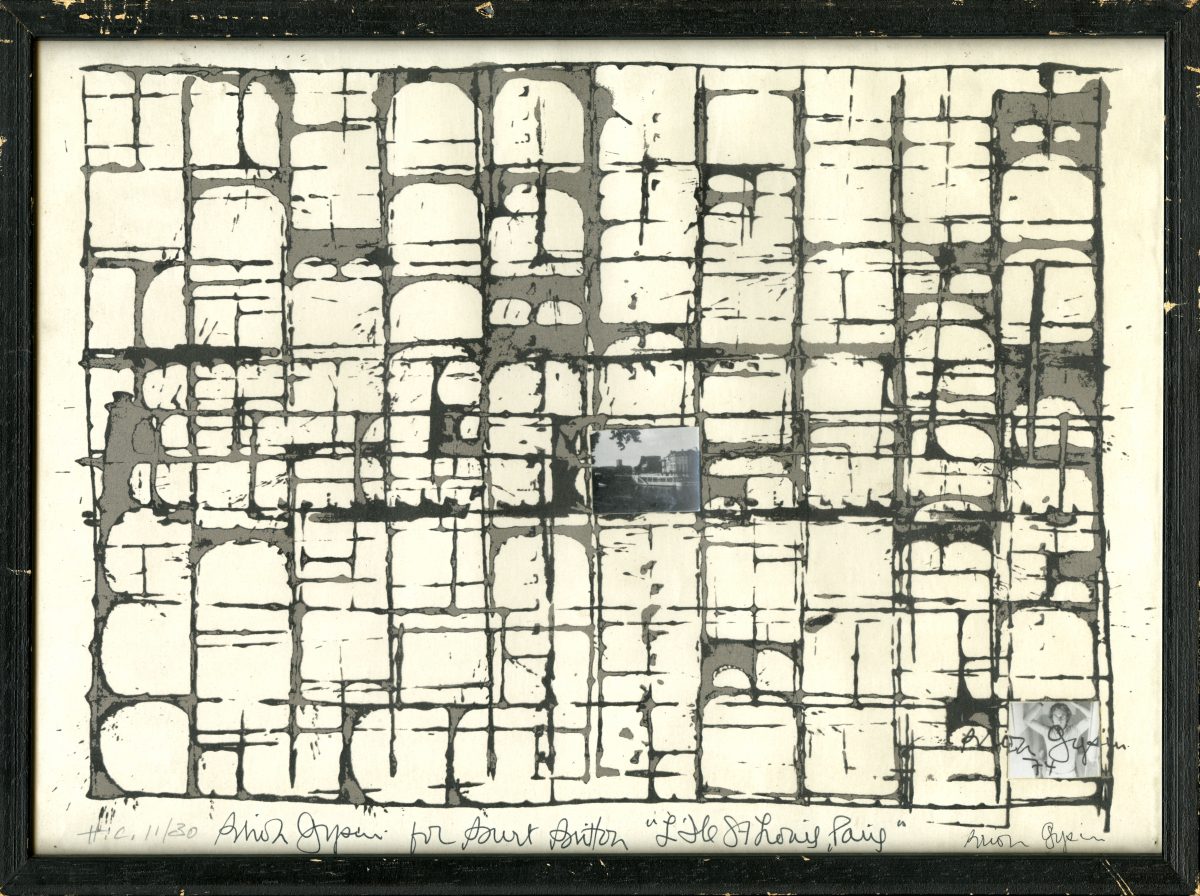

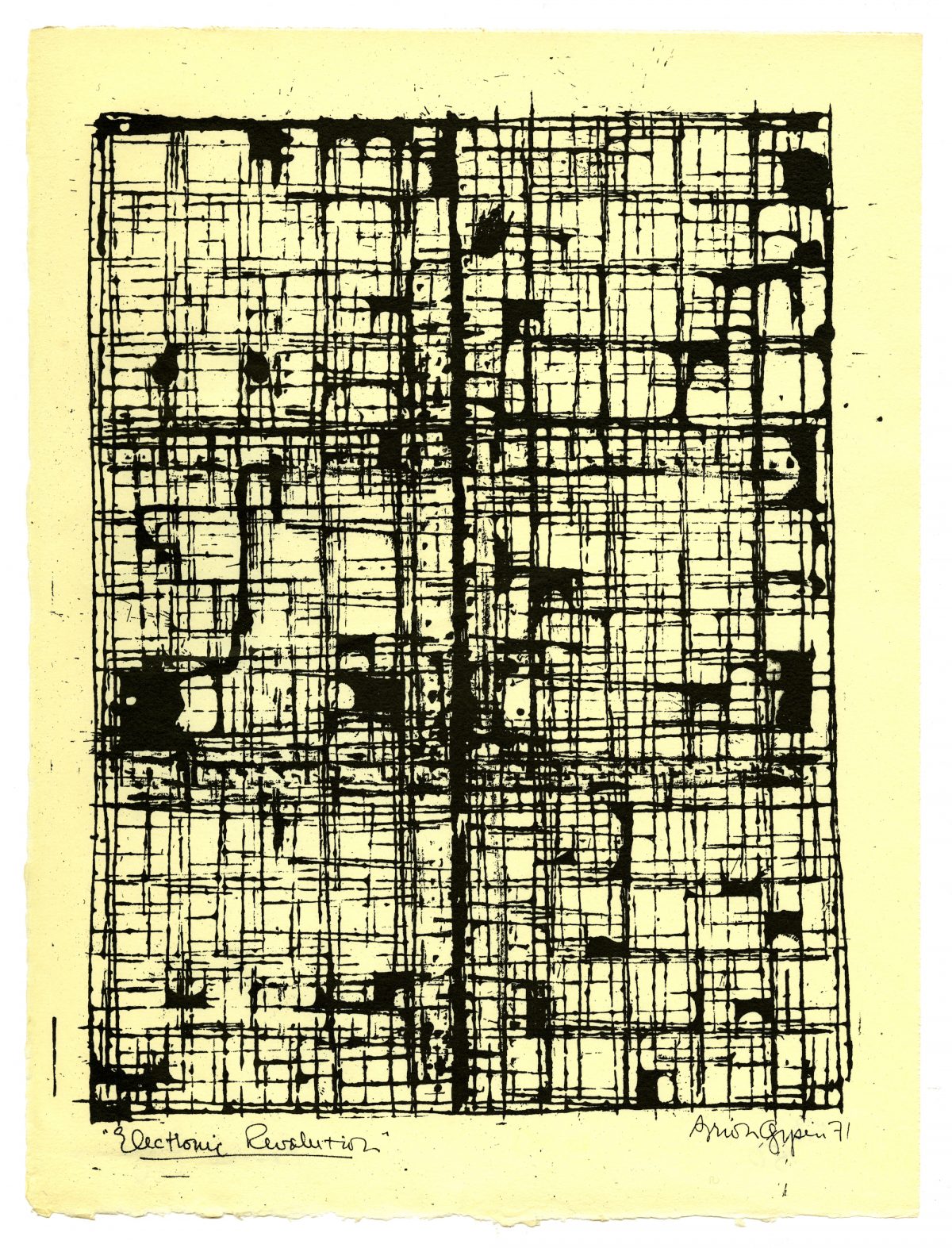

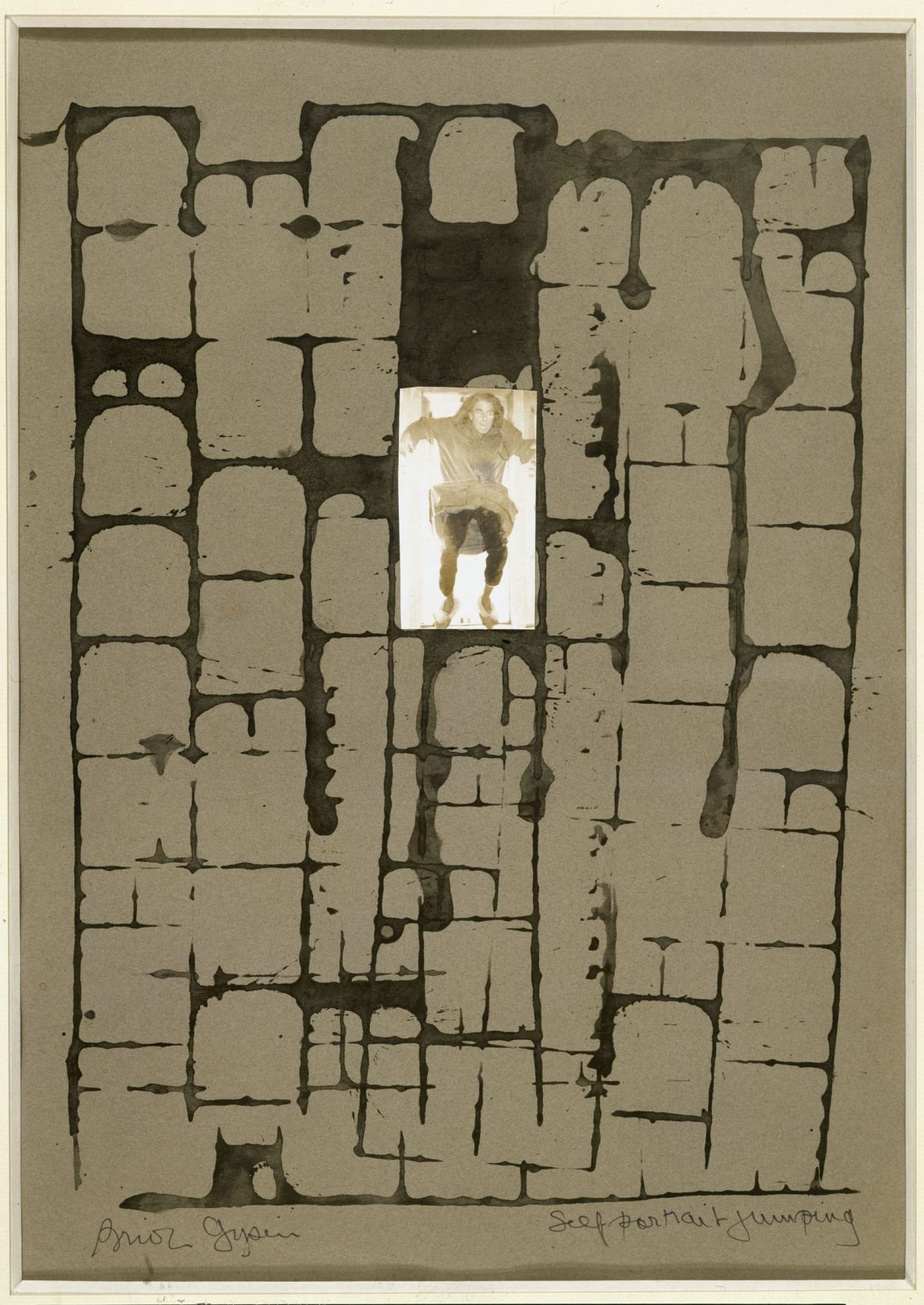

From this productive period came not only the cut-ups and the Dream Machine but also Gysin’s “roller grid” prints. “Repetitive yet always featuring distinct markings,” points out University of Delaware exhibition notes, “the roller grids represented an idiosyncratic system, an irrational order, combining repetition and chance. The principle of the “rolling grid” (endless repetition with endless variation) can be seen at work in many of Gysin’s and Williams S. Burrough’s projects, including the Dream Machine.”

One of Gysin’s roller grid prints, Self-Portrait Jumping, provided the title for a conceptual sound-art project that features Gysin’s readings of his poetry and stories over avant-garde compositions by Ramuntcho Matta, including the over 30-minute raga “Dreamachine.” The machine would continue to inspire, providing a subject for the 1997 documentary Flicker, further up, a thorough survey of Gysin and the only piece of art made for looking at with eyes closed.

Text from The Third Mind, by Brion Gysin and William S. Burroughs

Brion Gysin, L’Ile St. Louis, Paris, 1974

Brion Gysin, Electronic Revolution, 1971

Brion Gysin, Self-Portrait Jumping, 1974

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.