The Bright Young Things at Wilsford, 1927 (Cecil Beaton at far right)

In the years between the wars, the pent-up demand for pleasure and creativity exploded. This was the Jazz Age, the age of Weimar cabaret culture, the Lost Generation in Paris, and of London’s Bright Young Things, a collection of Bohemian artists and socialites whom Evelyn Waugh showed in his satiric 1930 novel Vile Bodies “could match up with the Paris contingent drink-for-drink and affair-for affair.” The conservative Waugh had little sympathy for this coterie and portrayed them as flamboyant, superficial, and “emotionally empty” writes literary scholar Naomi Milthorpe. His descriptions capture the excesses of the decade as a whole:

… Masked parties, Savage parties, Victorian parties, Greek parties, Wild West parties, Russian parties, Circus parties, parties where one had to dress as somebody else, almost naked parties in St John’s Wood, parties in flats and studios and houses and ships and hotels and night-clubs, in windmills and swimming-baths, tea parties at school where one ate muffins and meringues and tinned crab, parties at Oxford where one drank brown sherry and smoked Turkish cigarettes, dull dances in London and comic dances in Scotland and disgusting dances in Paris – all that succession and repetition of massed humanity…

Waugh observed the group from a sneering distance, setting down antics “so madly and unmorally irresponsible,” went a contemporary New York Times review, “that beside them Scott Fitzgerald’s most defiant characters are staid and conservative.” Their visual representation, however fell to one of the members themselves, photographer Cecil Beaton, who staged theatrical spectacles to document the actors, artists, and intellectuals of the circle and members of his own family.

Nancy and Baba Beaton, 1924

Beaton’s first published photographs, in fact, were of his socialite sisters Nancy and Baba, in the Tatler. Soon afterward, he met Dorothy Todd, editor of Vogue, and published his first photo of hundreds for the magazine, depicting “university acquaintance, George ‘Dadie’ Rylands, dragged up as John Webster’s Duchess of Malfi,” AnOther magazine notes, “‘in the subaqueous light outside the men’s lavatory of the A.D.C. Theatre at Cambridge,’ as Beaton would write afterwards.”

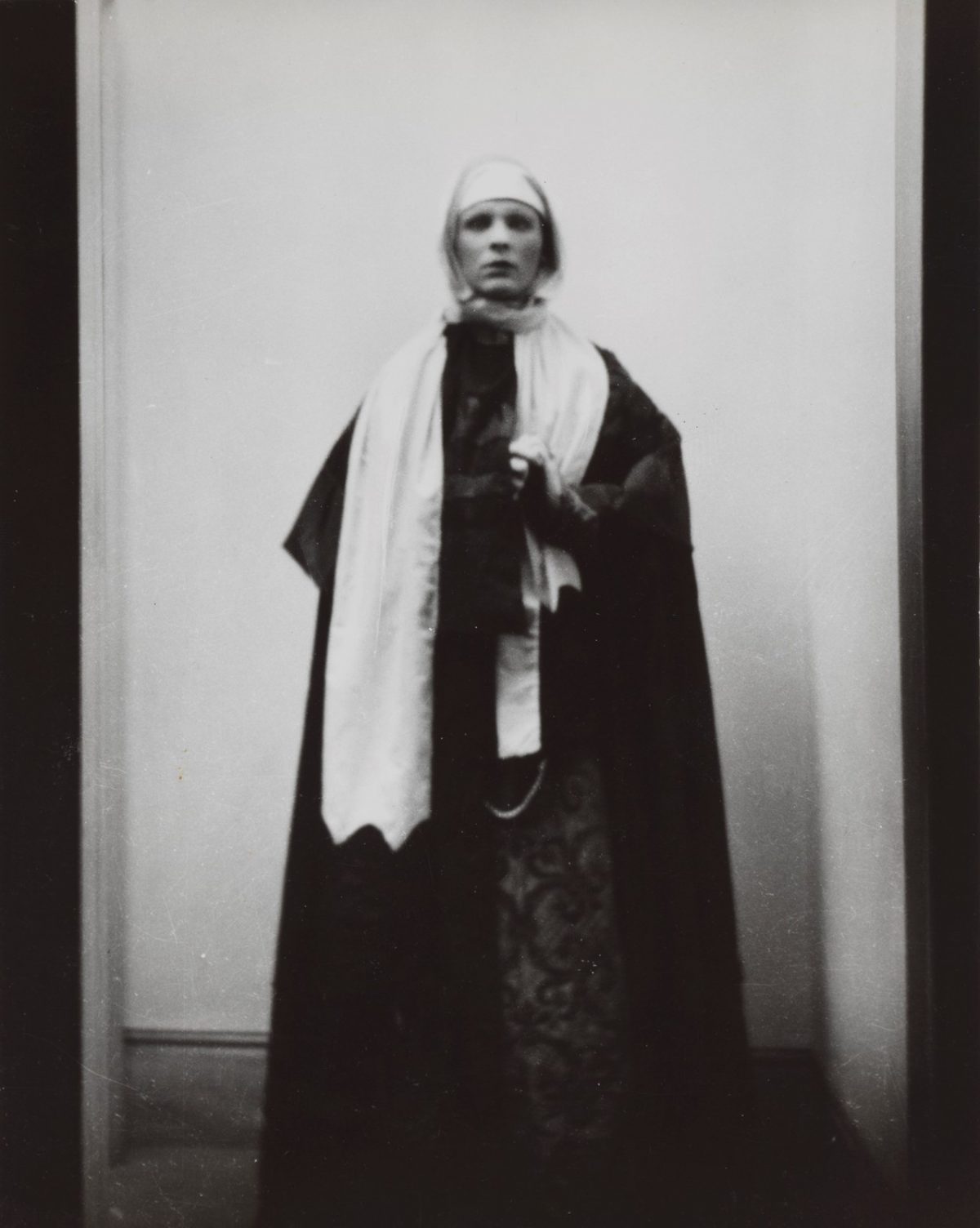

George ‘Dadie’ Rylands as the Duchess of Malfi, 1924

The image “was an early indication of his style: swooning and romantic portraits of Britain’s thinking classes, where broad strokes of fantasy and artifice stood as a defiant rebuke to the austerity of post-war life. They were preoccupations which would follow Beaton throughout his life,” showing up, for example, in the rehabilitation of the royal family in his post-WW II role of court photographer for the Windsors.

Beaton was an odd character. He was certainly more than he seemed to his contemporaries, including Waugh, who had attended prep school with Beaton and “bullied him cruelly,” Selina Hastings writes at the Tatler. In his first novel, Decline and Fall, Waugh turned Beaton into photographer David Lennox, and introduced as having “emerged with little shrieks from an Edwardian electric brougham and made straight for the nearest looking-glass.” Beaton could be vicious and catty (He once called Richard Burton “as butch and coarse as only a Welshman can be” and Katherine Hepburn “a rotten ingrained viper.”) Well known for his “elegance and bitchery,” the photographer happily described himself as a “scheming snob.”

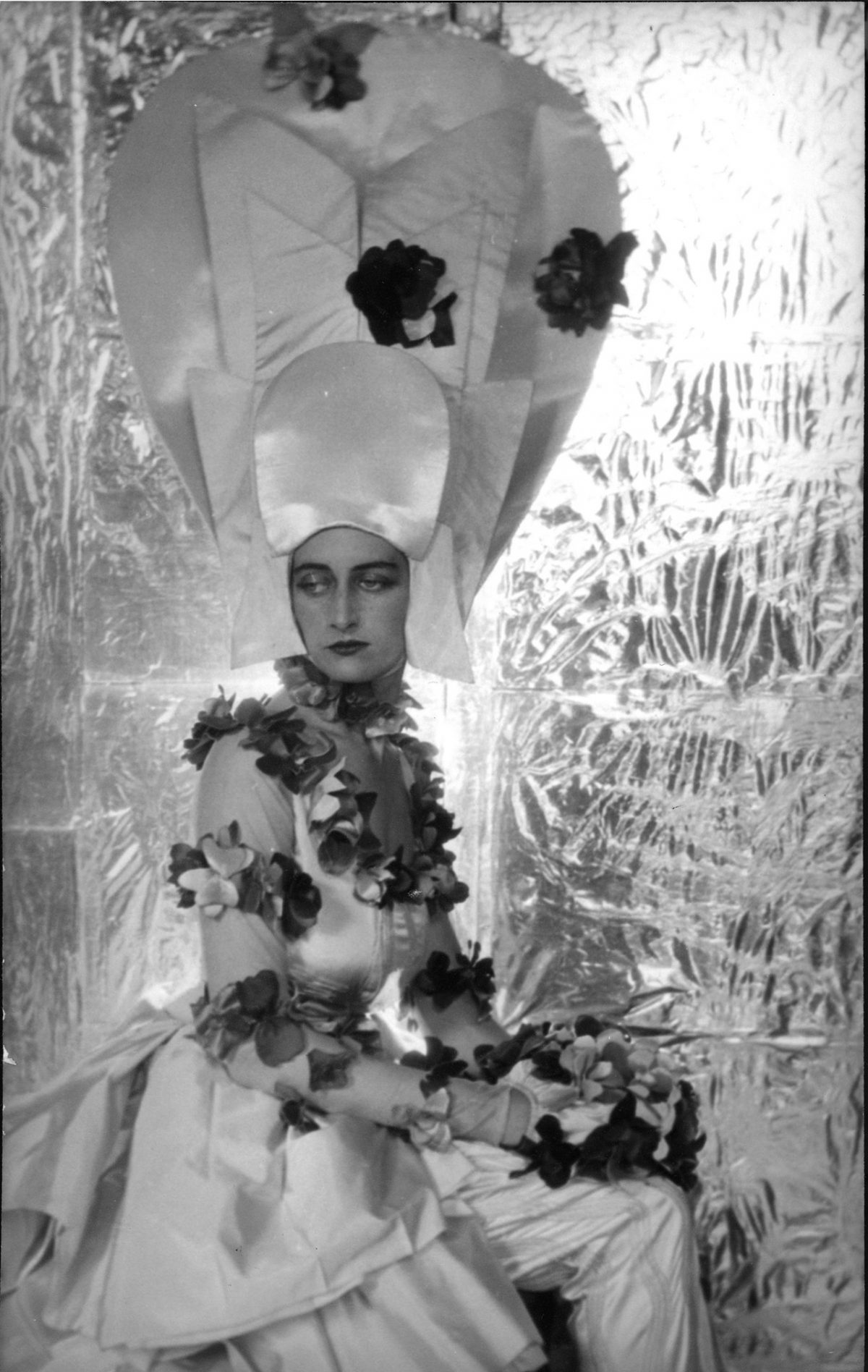

Edith Sitwell at Sussex Gardens, 1926

In depictions from the time, the Bright Young Things, aside from their aristocratic pedigree and artistic renown, resemble nothing so much as addled modern club kids or vapid 21st century influencers. Beaton was their Warhol, part of the scene and also its primary scenarist, “both observer and recorder,” Hastings writes, “as well as eager participant, appearing in pink satin and heavy make-up as a 17th-century dandy, as the Madam of a brothel, and in a coat covered in broken eggshells and roses.”

On the other hand, there was more substance to Beaton that Waugh would allow, and more than Beaton himself knew during the 20s. When the extravagance came to its inevitable end, “Beaton proved to be a profoundly accomplished, in unconventional war photographer,” writes AnOther, when the Ministry of Information sent him “from Britain to China, the Middle East, Africa, and India.” Beaton would later remark, “the war has pitchforked me out of my self-made rut into all sorts of different worlds.”

War was, in a sense, “the making of” Beaton, as Imperial War Museum curator Hilary Roberts comments. It gave him a sense of his capacities beyond the endless parties. But it did not change his essential orientation toward fantasy and glamor. Beaton would go on to photograph some of the most renowned figures of the 20th century and win Academy Awards for his costume design. The scene of the Bright Young Things may have been frivolous, but its cultural influence remains in every campy, over-the-top celebration of pleasurable excess.

via Monovisions

Baba Beaton and Prince Galitzine, 1927

Anne Armstrong-Jones, 1928

Edward Le Bas as Mrs Vulpy in The Watched Pot, 1924

Zita and Teresa Jungman, 1927 Cecil Beaton

Mrs Beaton, c. 1925 – Cecil Beaton

Nancy and Baba Beaton, 1926

Maxine Freeman-Thomas, 1928

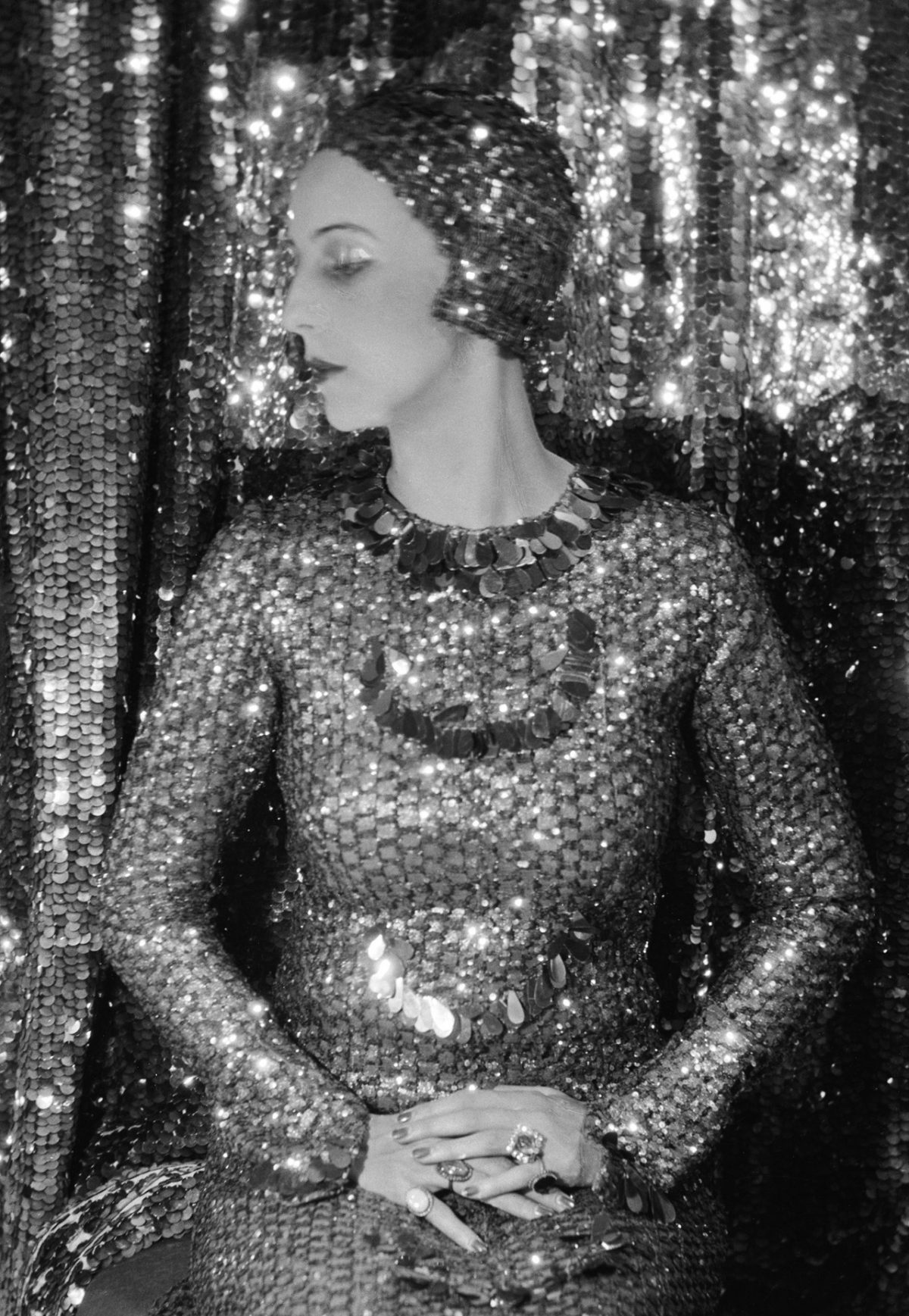

Anna May Wong, 1929

Oliver Messel in his costume for Paris in Helen!, 1932

Paula Gellibrand, Marquesa de Casa Maury, 1928

The Silver Soap Suds (L to R: Baba Beaton, the Hon. Mrs Charles Baillie-Hamilton and Lady Bridget Poulett), 1930

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.