George Hunter of the Charlatans never shot Jerry Garcia of the Grateful Dead, not even once. But in the spring of 1966, on the grounds of Rancho Olompali just north of San Francisco, Garcia had reason to believe Hunter was gunning for him, causing the great guitarist to royally freak out. The misunderstanding unfolded when Hunter decided to drop some LSD and bring a loaded .30-30 Winchester rifle to a party at the Dead’s new Marin County hangout. Hunter never intended to strike fear into the heart of his genial host, but when he did, he was so high that he began to panic—perhaps he had accidentally shot someone, if not Garcia, after all. It took a long bummer of a night, and three of Hunter’s closest friends, to shake that demon thought from his troubled mind.

“I said, ‘How would you like to be looking down the barrel of this thing?’”

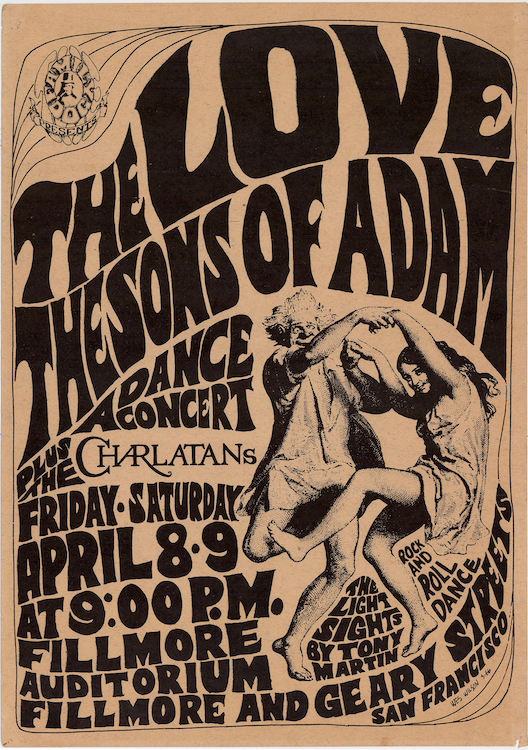

You’ve probably never heard of the “Incident at Olompali,” as no one has called it since, and your awareness of the Charlatans is likely limited to seeing the band’s name on scores of vintage rock posters, alongside more familiar monikers such as Jefferson Airplane, Quicksilver Messenger Service, Big Brother and the Holding Company, and Grateful Dead.

That’s too bad, because in their heyday, from 1965 to 1968, the Charlatans were a lot of people’s favorite band, thanks to a danceable mix of distinctively American musical genres—from the blues and rock to Western swing and jazz. Around the time of the Charlatans’ first paying gig, in June of 1965, the Grateful Dead were still playing pizza parlors as the Warlocks, Jefferson Airplane had yet to take off, Big Brother was a year away from handing Janis Joplin a microphone, and Quicksilver was not even a gleam in anyone’s eye. By 1966, the Charlatans had a record deal with the same label that had released the 1965 smash hit Do You Believe In Magic? by the Lovin’ Spoonful.

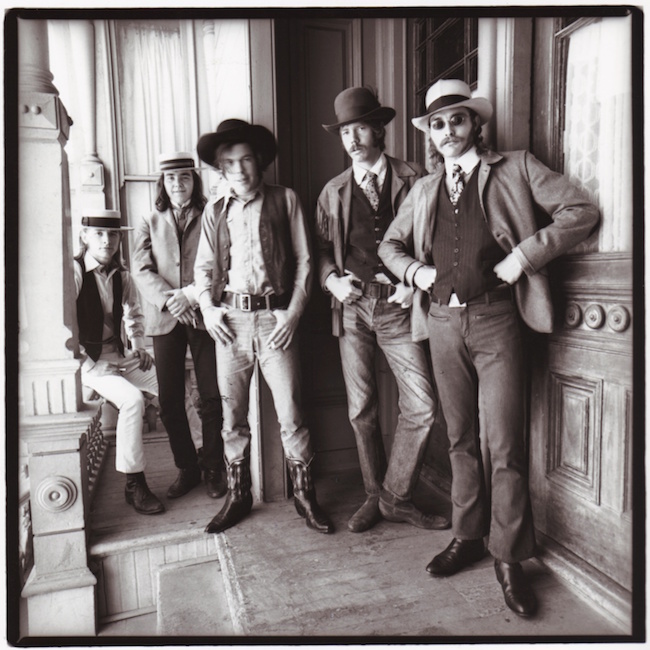

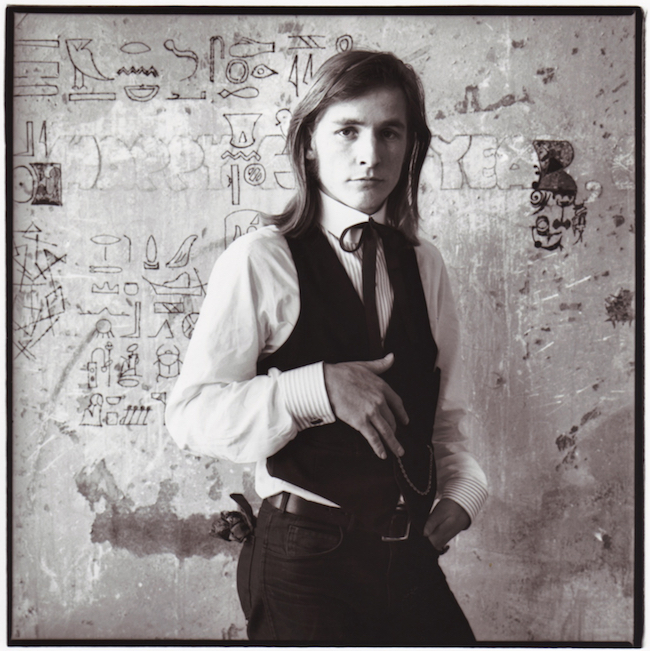

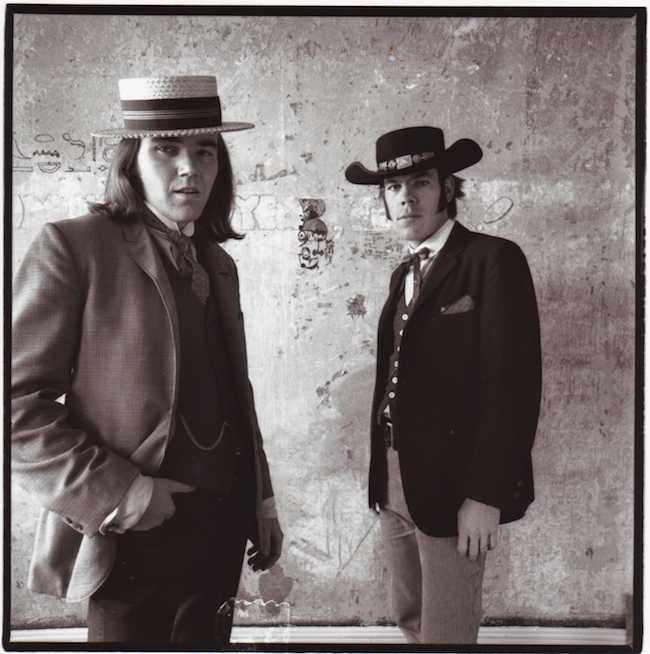

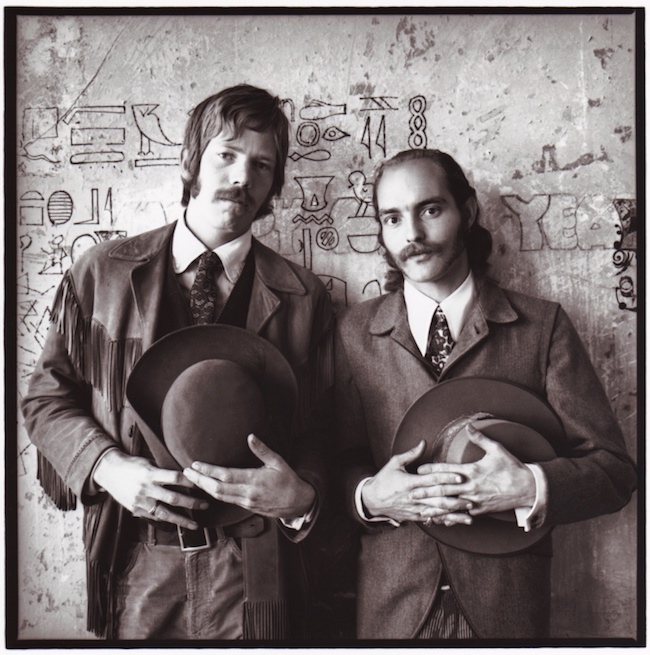

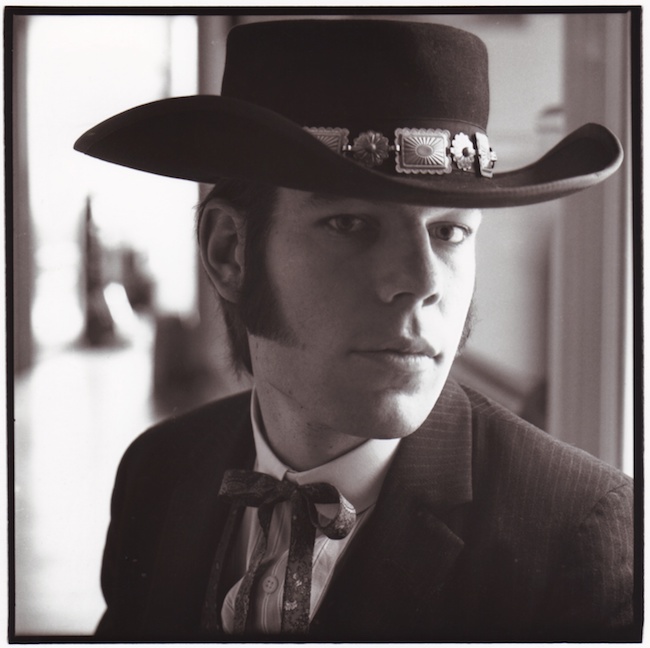

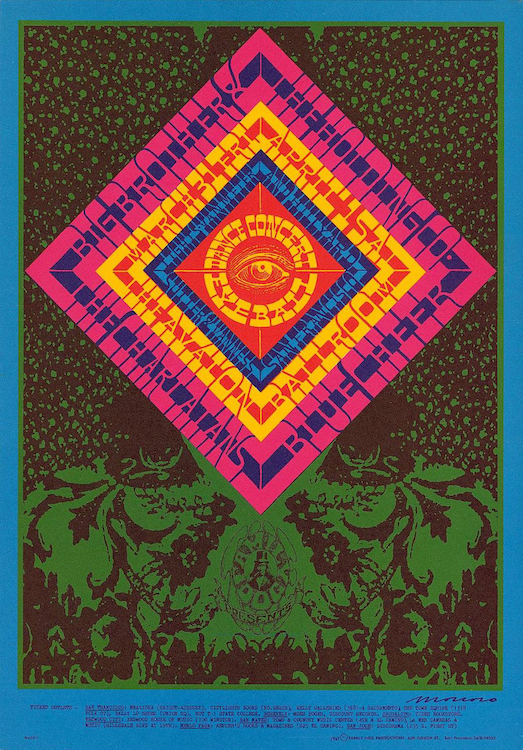

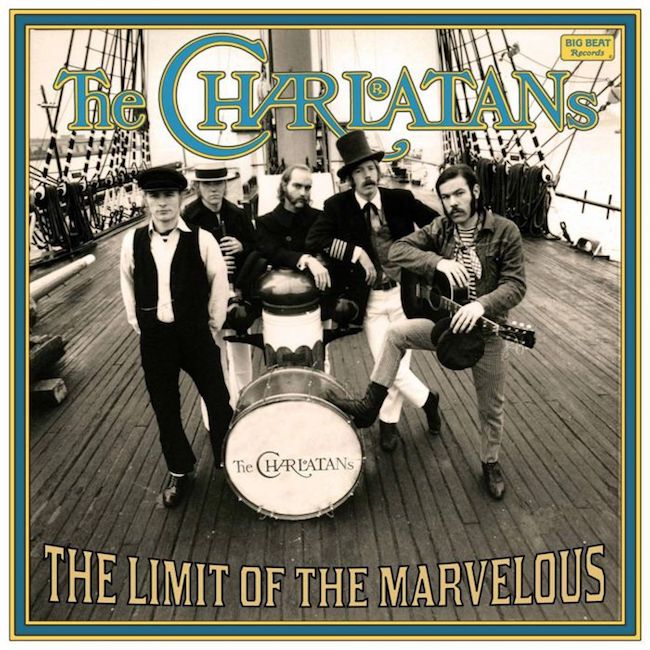

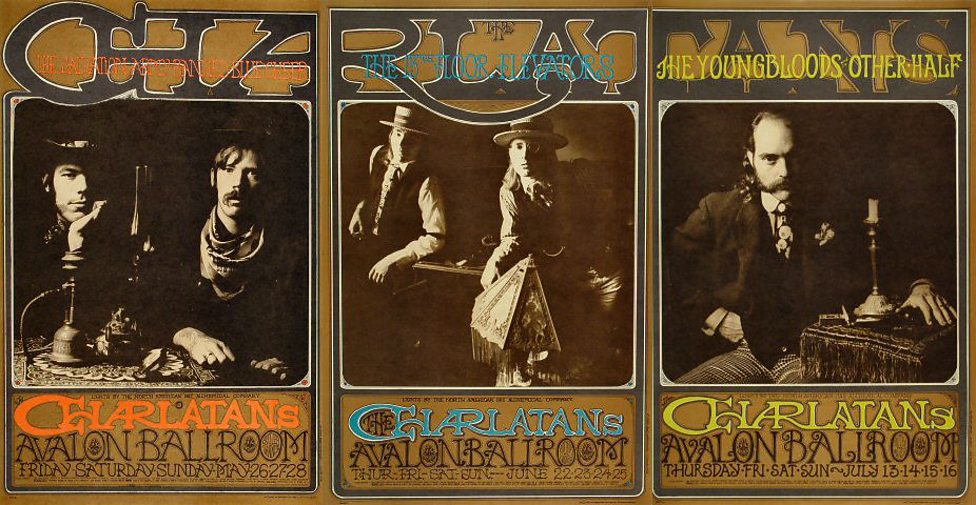

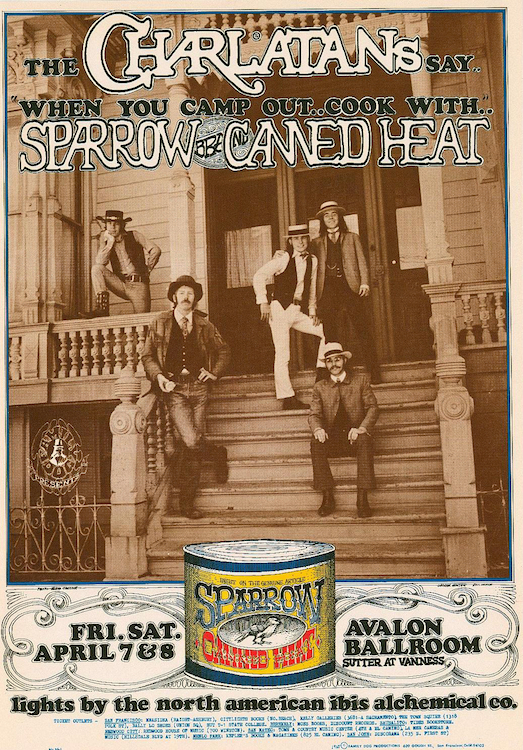

The Victorian-outlaw look of the Charlatans was captured best by photographer Herb Greene, whose photographs of the band were used in three posters by Rick Griffin and Robert Fried for shows at the Avalon Ballroom in May, June, and July of 1967. The band members in the top photo, from left to right, are George Hunter, Richard Olsen, Mike Wilhelm, Dan Hicks, and Mick Ferguson.

Given their head start as performers, the Charlatans should have been one of the biggest music acts of the 1960s. They were doing acid tests before anyone even called them that, and were the first band to promote itself with a poster and perform while bathed in the glow of a light show. Just as importantly, the Charlatans were trailblazers at a moment in musical history when rock bands were being rewarded for conforming to the new psychedelic orthodoxy. In particular, the band’s embrace of Americana was years ahead of the Byrds, Grateful Dead, and Eagles, who also wove threads pillaged from those genres into their repertoires. That’s not to give the Charlatans credit for “Sweetheart of the Rodeo” and “Workingman’s Dead”—or blame for “Desperado”—but they got to the Americana party first.

All of this should have worked in their favor, but by the Summer of Love in 1967, the band was self-destructing, and by the time Jimi Hendrix was playing the last notes of “Hey Joe” at Woodstock in the summer of 1969, the Charlatans were history. What happened?

This uniquely San Francisco story begins, as many do, in Los Angeles. That’s where the band’s co-founder and leader, George Hunter, first laid eyes on the future mother of his children, Lucy Lewis. “We met at San Fernando Valley State College around 1961,” Lewis recalls. “I was a dancer taking classes; he was this boy-genius architect.”

“Architecture was my forte, or whatever you’d call it,” Hunter says. “In high school, I had a job as an office boy at William Pereira & Associates, which was designing the Los Angeles County Museum of Art at the time. I would stay late, drawing trees on plans, dumb things like that. Eventually, I worked for a company that was making the presentation models for Pereira. That was more sophisticated—we made our own injection molds.”

Because Hunter had a good friend attending San Fernando State, he often hung out on campus, which is where he first spotted Lewis. “He just started following me around,” Lewis says, which was fine with her. “He knew where all the best parties were. We went to all the cool places, like Pogo’s Swamp and the 5th Estate. We had a lot of fun.”

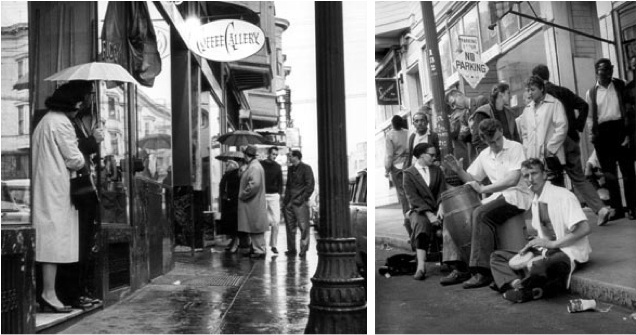

When Lewis transferred to San Francisco State College in 1962, Hunter followed her there, too. And that’s how he met his future co-founder of the Charlatans, Richard Olsen, who’d left Chicago a year or so earlier to study jazz and maybe, just maybe, make it as a musician in the vibrant jazz scene in San Francisco’s North Beach neighborhood.

Charlatans co-founder Richard Olsen was lured to San Francisco in 1961 by the beatnik jazz scene in North Beach, seen here in 1959 (left) and 1961 (right). Photos by Jerry Stoll.

“I actually met Lucy before I met George,” Olsen says. “She was a dancer, and I was a music major, studying clarinet—we were both in the creative arts department at San Francisco State.” Before long, Hunter and Olsen were collaborating with Lewis on the dance performances she was choreographing with her roommate, Joan Alexander. Lewis recruited Olsen to be one of her dancers. Hunter, whose interest in hi-fi audio components was as keen as his affinity for architecture, provided the sounds.

“George was into in tape music,” Lewis says, referring to a genre of prerecorded audio championed by composer John Cage. “We gave him this little broom closet to work in, and he transformed it into a music studio.”

“I had one of those old Ampex tape machines in the brown leatherette case,” Hunter remembers. “I would record lots of different tones on a tape, cut it up into little pieces, and then reassemble it to get all these weird sounds.” “You’d go in there, and there’d be all these pieces of tape hanging in little loops,” Lewis recalls. To produce one weird sound captured on one of those little loops, Hunter removed the needle from a phonograph cartridge and replaced it with the end of a Slinky. “I used the cartridge like a contact mic—that’s basically what it was. You could take the needle out and put anything in there to generate all different kinds of sounds.”

The San Francisco Tape Music Center at 321 Divisadero was an early creative outlet for George Hunter. He provided sounds for his girlfriend Lucy Lewis’ dance-and-theater company—it was called 123 in an inverted homage to the center’s address—which performed there, and Hunter even made the center’s sign out front.

The San Francisco Tape Music Center at 321 Divisadero was an early creative outlet for George Hunter. He provided sounds for his girlfriend Lucy Lewis’ dance-and-theater company—it was called 123 in an inverted homage to the center’s address—which performed there, and Hunter even made the center’s sign out front.

For a while, Hunter and Olsen were active members of Lewis’ avant-garde theater-and-dance company, which she called 123—the name was a play on the addresses of the San Francisco Tape Music Center at 321 Divisadero Street, where 123 sometimes performed. In retrospect, though, Hunter and Olsen’s enthusiasm for 123 may have been because the two young men were at loose ends. At some point in 1963, Olsen was kicked out of SF State because his hair was too long, even though his locks were partially obscured by a hat. “I wore one of those newsboy caps, like Bob Dylan did,” Olsen remembers. As for Hunter, he was experimenting with a new business opportunity in the counterculture economy. “I used to go down to Los Angeles, score a couple of kilos of grass, and bring it back. You could get twice as much for it in San Francisco,” he says matter-of-factly.

Hunter still had a lot of friends and contacts in L.A., among them Mike Wilhelm, who had been a classmate of Hunter’s at Canoga Park High School. Wilhelm would become the Charlatans’ lead guitarist, but during the period when Hunter and Olsen were performing with 123 up in San Francisco, Wilhelm was doing a two-year stint in the Naval Air Reserves, which took him from his base at Los Alamitos, just south east of downtown Los Angeles, all the way to the coast of Vietnam. Between assignments, he gave himself the musical education that would become such an important part of the Charlatans’ sound.

“I had a cheap Harmony guitar,” Wilhelm says. “It didn’t look good or sound so hot, but it was something to learn on.” One of the first songs Wilhelm taught himself was “Peggy Sue” by Buddy Holly, but he soon fell in love with the blues. “I listened to all the blues 45s and 78s in my big sister’s record collection,” he says. “Then I started hanging around coffeehouses and hearing folk music, which got me interested in acoustic blues.”

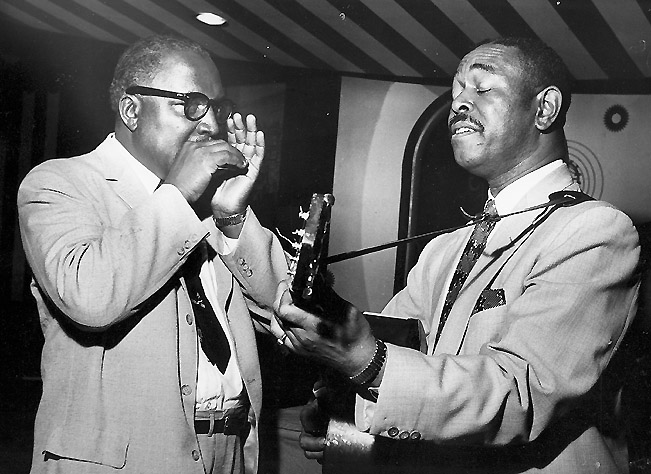

The biggest early influence of Charlatans guitarist Mike Wilhelm was Brownie McGhee (right), seen here at the Marquee Club in London with his longtime performing partner, harmonica player Sonny Terry. Via Chris Barber LP Collection.

During this period, from roughly 1961 to ’63, Wilhelm gravitated to the music of Sonny Terry and Brownie McGhee. Naturally, Wilhelm was especially interested in McGhee’s guitar playing, which is why it was such a thrill for the young guitarist to meet his hero. “It was just by chance,” Wilhelm says of his first encounter with McGhee. “I had my guitar with me, so I asked him how he fingered his signature turnaround, which is where the end of one verse goes into the next. He said, ‘Let me see your guitar,’ and he showed me the fingering. A week later, I ran into him again. By then I could play his turnaround, so he showed me some other things. Pretty soon he was giving me lessons, except he wasn’t charging me. He just kind of took me under his wing.”

“I listened to all the blues 45s and 78s in my big sister’s record collection.”

Armed with McGhee’s advice about how to find his own sound as a musician—”he taught me a lot of stuff that at the time I didn’t even know I needed to know”—and finished with his commitment to the Naval Air Reserves, Wilhelm hitchhiked to Northern California at the end of the summer of 1963, intent on making it as a musician. “I met some guitar players on the road,” he remembers. “They were attending Cal, so I settled in Berkeley, renting the sort of room a student would have rented.” Wilhelm soon found himself playing guitar in the house band of a “frat rat” hangout called the Monkey Inn. “It was painted black inside, with Greek letters on the walls, sawdust on the floor, and these red-checked tablecloths. We played a lot of instrumental surf music, which is how I got into the electric guitar, learning how to use echo boxes, and all that stuff.”

On some of his days off, Wilhelm would play open-mic nights in folk-music clubs. “One place I played was the Cabale down on San Pablo Avenue. The kids in the folk scene there, the folkies, were supposedly these nonconformists, but they all wore the same uniform—blue chambray work shirts, faded Levi’s, and Acme roughout cowboy boots—all of them.”

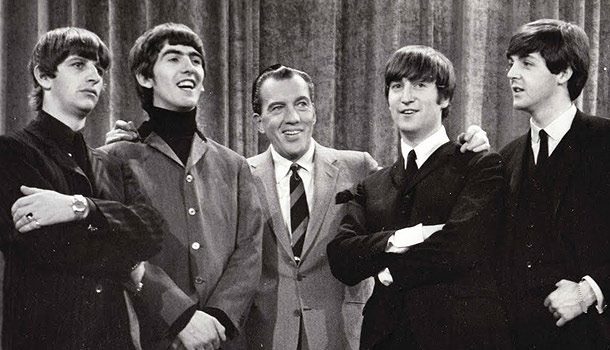

Wilhelm also did open mics at the Blue Unicorn on Hayes Street in San Francisco, which is how he reconnected with George Hunter, bumping into his old friend on the street. By the summer of 1964, Wilhelm was living in Hunter and Lewis’ flat at 200 Downey Street, just up the hill from the Haight-Ashbury neighborhood. The pieces of the Charlatans were coming together, but the catalyst for the formation of the Charlatans had actually occurred a few months earlier, on February 9, 1964, to be exact, when The Beatles first appeared on “The Ed Sullivan Show.” The live telecast was watched by an estimated 73 million American viewers, about a third of the entire U.S. population at the time.

No doubt countless U.S. musicians were inspired to start their own bands after seeing The Beatles perform on “The Ed Sullivan Show” on February 9, 1964. George Hunter was watching that night, too.

Two of those Americans were George Hunter and Chet Helms, the future impresario of the Family Dog, which produced regular concerts at the Avalon Ballroom between 1966 and 1968—many of those shows would feature the Charlatans. “Chet and I went over to somebody’s house where there was a TV and watched ‘The Ed Sullivan Show’ until The Beatles came on,” Hunter remembers. “They were such a radical departure from everything else at the time. Pop music was no longer just bubble gum.”

“The music that preceded The Beatles were songs like ‘Sugar Shack,’” Olsen adds. “Radio stations were playing all this really corny crap.” The Beatles were also an antidote to the most tumultuous event of the early 1960s. “Coming on the heels of the Kennedy assassination, The Beatles were so positive, so joyful, and fun. The timing was perfect. And that’s when we got the idea that we should put together a band.”

“It was, like, ‘Well, gosh, we could do that!’” Hunter says.

“I didn’t want to be a clarinet or sax player in a Beatles- or Rolling Stones-type band,” Olsen continues. “I wanted to play an instrument that would allow me to sing, so I ended up learning bass, but we still needed a guitar player. Then, one day, George says, ‘I know this guy. He plays at the Blue Unicorn.’” Enter Mike Wilhelm, followed by Mike Ferguson (1942-1979), who was an antiques and vintage-clothing dealer, a graphic artist, and a pianist. Drummer Sam Linde, who lived upstairs from Hunter and Lewis, was the last to join the band’s initial lineup and the first to be replaced—within a few months, Dan Hicks (1941-2016) was sitting behind the drum set.

Ironically, as the band’s leader, Hunter didn’t play an instrument, but his musical instincts were strong, and he could bang a tambourine and strum an autoharp with the best of them. “Actually, George did some really cool stuff with the autoharp,” Wilhelm says. “If there were chords on a song that weren’t on the autoharp, he’d cut up some felt blocks, make a new chord bar, and put it in the instrument. He sang some good vocals, too.”

As it turned out, Hunter’s limitations as a musician allowed the talents of the other band members—Ferguson’s barrelhouse piano, Olsen’s fundamentals in jazz, Hicks’ fondness for folk and swing, and Wilhelm’s blues bona-fides—to shine, giving the Charlatans its distinctive sound.

“They started practicing in our house,” Lewis says of the period from the fall of 1964 through the spring of 1965. “The front room hosted rehearsals 24 hours a day. There was big waffle padding all over the place.”

“We’d play some Chuck Berry, a lot of blues, some songs Wilhelm knew,” Olsen says. “We were just kind of getting our chops together, in that stumbling block period of learning to walk. We didn’t have any gigs lined up; we didn’t even have a proper name.”

By Olsen’s count, four names were tossed around at various points. Fifth Column never stood a chance (too intellectual), but the Androids briefly stuck. In part, the name was an homage to one of Hunter and Wilhelm’s literary heroes, Ray Bradbury, who used to give readings at Coffee House Positano in Malibu, which the two high-school friends used to frequent. “George had this idea that we’d play electronic music, and we’d be in these androidy costumes, sort of like Devo, but about 20 years earlier,” Wilhelm says.

For several months in 1964, Hunter, Olsen, Wilhelm, Ferguson, and Linde rehearsed as the Mainliners. That fall, after Hicks joined the group, they settled on the Charlatans. “George’s mother used to call him that,” Olsen says. “Everybody thought it was a great name for the band.”

Everybody, that is, except maybe Lucy Lewis, whose vision of building a successful dance-and-theater company could not compete with her boyfriend’s dream of being an American version of The Beatles.

“Lucy was probably frustrated because she was a performer and a dancer, and she wanted to pursue her career,” Olsen says. “She was going for it, and George had been the main one helping her put her shows on, so when we started pursuing the Charlatans, that left her hanging.”

“It was a difficult time for me,” Lewis says. “I was the director of this theater-and-dance company, I thought we were really creating something unique, and I wanted it to keep going. But it was like the energy just started moving away. Two of the company’s members joined The Living Theatre in New York, another one went to India, and George and Richard started the Charlatans.”

Lewis also couldn’t compete with the drugs. “Before I moved to San Francisco,” Hunter says, “I was warned about all the methamphetamine. No sooner did I get up here that I started doing meth, and then heroin.”

“I would go down to L.A., come back, and things would have gotten worse and worse,” Lewis says. “It was a very emotional time.”

For those who were not there, it may help to explain that in the 1960s, there were “drugs” and there were “hard drugs.” Marijuana and LSD, the latter of which was legal in California until October of 1966, were drugs—lots of people took drugs. Meth and heroin were hard drugs—speed freaks and junkies took hard drugs.

According to Lewis, the use of speed and smack “wasn’t prevalent” in 1965 and 1966. “You had a few junkies here and there, but it wasn’t the overarching tone of what was going on,” she says. “Mostly people were just smoking a lot of pot and taking LSD, tripping around, having fun. But then, slowly, the harder drugs just kind of ate their way into the texture of the whole scene.”

To hear Hunter tell it, heroin may have actually gotten in the way of bringing Janis Joplin into the Charlatans, before she joined Big Brother and the Holding Company. “She was singing a lot of old-time blues, so she would’ve been perfect for the Charlatans,” Hunter says. “We were doing the blues and old-time stuff, too, whereas Big Brother was all psychedelic. But I used to be, like, Janis’ connection, so I didn’t even go down to see her at this coffeehouse where she was singing, which was really stupid. I already knew her in this other context that was not really favorable.”

In others words, the Charlatans already had one junkie in the band—that was enough.

“I never heard about that,” Wilhelm says of Hunter’s Joplin regret, “but I can see how George might have had that as an idea in his head that he never followed up on. Chet Helms was kind of shepherding Janis around, and I think that’s how she wound up in Big Brother. It was certainly a better fit for her than the Charlatans.”

Olsen also isn’t so sure Janis Joplin would have ever become a member of the Charlatans, although he doesn’t exactly dispute the drug part of Hunter’s story. “She used to come over when we were rehearsing,” he says, “as did Grace Slick. I knew Janis was a singer, but she never sang anything when she was here. But she used to come over, for, whatever,” he says, trailing off.

“Sometimes I wonder how I could have been so oblivious to so much at that time,” Hunter says, adding quietly, in answer to his own question. “The fact that maybe I had a drug problem?”

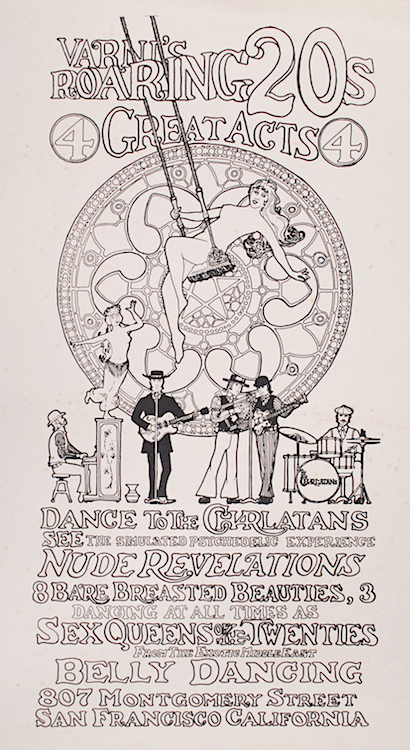

“Varni’s obviously catered to a different crowd than the Fillmore and Avalon.”

Drugs aside, the work of turning Hunter, Olsen, Wilhelm, Ferguson, and Hicks into the Charlatans got done. For example, immediately after that “Eureka!” moment when the Mainliners were suddenly the Charlatans, Hunter sat down and designed what would become the band’s logo. “Right then and there,” Olsen remembers, “George started drawing the lettering for the name.” Wilhelm remembers the same thing, and that lettering would be used on everything from the first poster for the band’s first show in 1965 to its debut album, which was released in 1969, too late to help the band’s fortunes. By then, Wilhelm and Olsen were the band’s only original members, and within a few months, what was left of the Charlatans would dissolve for good.

As an old-fashioned word from another era, “Charlatans” fit the look Hunter wanted for the band’s attire, in which they dressed up as Victorian and Edwardian dandies, a style that complemented San Francisco’s pervasive Victorian and Edwardian architecture. It was also a look that mirrored, but did not copy, the uniformity of the clothing worn by The Beatles. Best of all, the band’s new name was a lighthearted punctuation mark on the tight-fitting vests, starched collars, paisley neckties, and straw skimmers worn even during rehearsals. “Who are these curious fellows,” one could imagine a full-bellied and extravagantly mustachioed character from a black-and-white “Sherlock Holmes” movie huffing and puffing, “these, these, … Charlatans!”

When Mark Unobsky bankrolled the Red Dog Saloon in the summer of 1965, he hired the Charlatans to be the house band.

Whoever they were, whatever they were, by the spring of 1965, the Charlatans were ready to leave the confines of Hunter and Lewis’ front room and take their show on the road. And as had been the case when Wilhelm happened to run into Hunter a year or so earlier, serendipity gave the Charlatans their first gig.

“Richie and I were over in North Beach,” Wilhelm says. “We were walking up Grant Avenue, and this car pulls over and a guy leans out and says, ‘Hey, are you guys the Byrds?’ And I said, ‘No, we’re the Charlatans.’ And he’s like, ‘You’re a band, then, right?’ And I said, ‘Oh, yeah, we’re a band.’”

The guy in the car turned out to be Chandler Laughlin, who’d been one of the owners of the Cabale, the folk club where Wilhelm had first played when he got to Berkeley. Laughlin was now involved in the remodel of a three-story, 1863 building in the old silver-mining town of Virginia City, Nevada, about a six-hour drive due east of San Francisco. Bankrolled by counterculture folk hero Mark Unobsky, the Red Dog Saloon, as the building’s ground-floor bar was renamed, would become an unlikely crucible for rock ’n’ roll and LSD in the high desert of Nevada.

“We brought Chandler over to George’s house,” Wilhelm continues, “gave him a funky demo tape we’d made, and he left. The next thing we know, he’s sending us gas money to go up there for an audition. We all wanted to go, except Dan, who was all, ‘Well, I don’t know.’ And we said ‘Come on, we’ve been rehearsing all this time, and now that we actually have a shot at a gig, you don’t want to do it? What’s wrong with you?’” According to Wilhelm, someone only half-jokingly suggested that they were prepared to knock Hicks out, tie him up, and toss him the trunk of their car, but eventually Hicks agreed. “I found out later that George had slipped him a hundred bucks to get him to change his mind.”

“Yeah, I’m pretty sure that happened,” Hunter confirms.

As clarifying moments go, the upcoming audition at the Red Dog was a big one for the Charlatans. “We’d been rehearsing at George’s, we had our name, and we were getting a bit of a repertoire together,” Richard says. “Then we were offered that audition, and we got really scared because now we had to perform. About a week before we went up there, we rehearsed in my place on Lee Avenue over by City College of San Francisco. I had somehow gotten these red velvet curtains from the old Fox Theater in San Francisco. I put them up on all the walls so we could play without causing a lot of noise. That was the last place we rehearsed before we drove up to Virginia City.”

It took a small caravan of cars to get the band members, assorted girlfriends, equipment, and those red velvet curtains, which Olsen eventually sold to Unobsky, to Virginia City. They arrived at dusk. “Driving through all that mining history at that time of day, with the sun going down, everything looked so magical,” Olsen recalls. “I don’t know why, but it just seemed so special.”

Upon arrival, the Charlatans learned that the Red Dog was still under construction. “There were, like, 20 or 30 guys working—painters, carpenters, plumbers,” Olsen remembers. “Many of them were getting paid in, uh, something other than money, so they weren’t quite ready. So they gave us these rooms upstairs to stay in, fed us good meals, and we waited.”

“The house salad at the Red Dog was Crab Louie,” Wilhelm says. “Even though the food was really good at the Red Dog, Crab Louie every night was a little much.”

“The delay gave us a chance to get acclimatized, so to speak, hanging out in places like the Bucket of Blood Saloon,” Olsen continues. “I remember sitting in a bar across the street from the Red Dog with Wilhelm, high on LSD, looking at all the photographs of old trains from the 1800s that were hanging behind the bar. In our state of mind, the trains in those photos were moving, just chugging along. We were really getting into the whole vibe of that era.”

Part of the vibe was captured via their attire, which now expanded beyond dandy duds to include clothes that might have been worn by late 19th-century outlaws. “When we got to the Red Dog, our persona really started coming together because of the Western influence of Virginia City,” Olsen says.

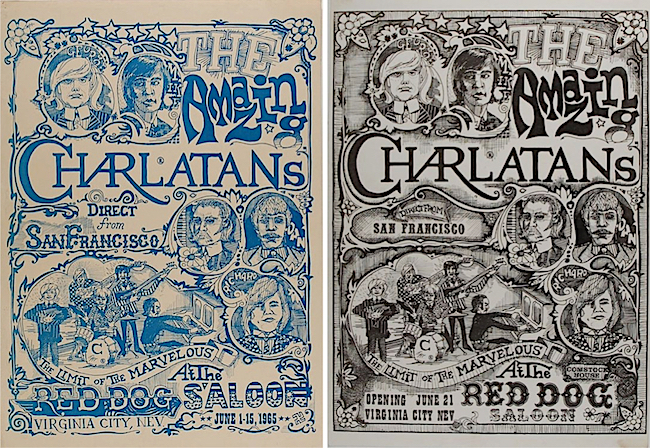

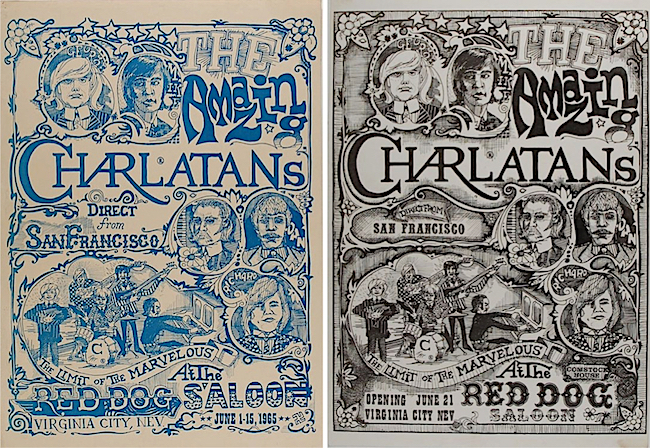

The two versions of the poster created by Mike Ferguson and George Hunter for the Charlatans’ 1965 shows at the Red Dog are both known as “The Seed” because the poster started the psychedelic-poster revolution that would flower the following year.

Guns were a part of this evolving look. “Mark wanted everybody to have a weapon,” Wilhelm says. “He sent us all up to Charlie Stone’s bar and arms museum to pick out a gun, and then he paid for them.” George Hunter’s .30-30 Winchester Carbine, the rifle that would scare the daylights out of Jerry Garcia at Rancho Olompali about a year later, was picked up during this Wild West shopping spree.

Inside the Red Dog, the Virginia City vibe would morph to include two more visual elements, each of which would be deemed essential to the coming dance concerts in 1966 at the Fillmore and Avalon. The first of these was the light show, which was an evolution of the lighting effects used by experimental theater companies like 123 throughout the early 1960s. Bill Ham was tapped to provide the light show for the Red Dog’s opening, but because he could not commit to moving to Virginia City to run the light show every night, he and a friend named Bob Cohen built a machine that would produce light effects automatically.

The second visual element was the concert poster, which Hunter realized was the only affordable form of media to get the word out about their shows. The poster for the Charlatans’ shows at the Red Dog, known in poster-collecting circles as “The Seed,” was actually designed by band member Mike Ferguson, who did the overall layout and the caricatures of the bands members, and George Hunter, who did the border, background, dates, and location information. Two versions found their way into circulation—either can bring five figures today. One of the posters was printed in a teal blue and features the dates “June 1-15, 1965.” The other was printed in black-and-white and is almost the same as the blue one, except for some of the lettering and the date, which reads “Opening June 21.” “That blue one was sort of a published press-proof kind of thing,” Hunter says. “The black-and-white one is the real deal.”

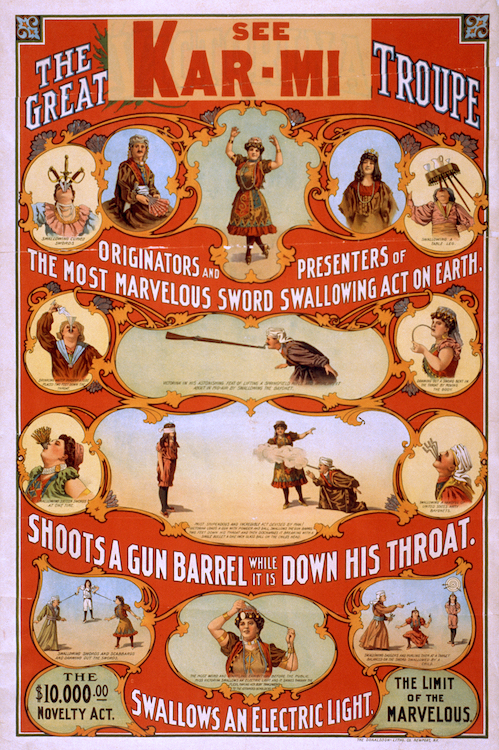

Mike Ferguson used elements from a 1914 poster for the Great Kar-Mi Troupe in The Seed poster for the Charlatans. The phrase at bottom-right, “The Limit of the Marvelous,” would also make its way onto subsequent posters for the band.

The Seed is often referred to as the first psychedelic poster, but compared to what would come later, there was nothing especially psychedelic about it. In fact, Ferguson took the general layout for The Seed from a 1914 poster for the “Great Kar-Mi Troupe,” which promised acts performing at “The Limit of the Marvelous,” a phrase that would find its way into many subsequent advertisements for the Charlatans.

With their wardrobe in hand, light show operational, and poster announcing the debut of “The Amazing Charlatans,” finally it was time to play. “About a week after we’d arrived, Mark Unobsky comes by to tell us that the audition would be that night, and we’d be playing for the whole staff,” Olsen recalls. “Mark had been going to each person’s room, saying, ‘Here’s a little sugar cube.’ So everybody in the whole place, not just us in the band, but everyone, was loaded on LSD.” To put this in its counterculture-history context, the first acid test conducted by author Ken Kesey and members of the Merry Pranksters, with music by the Grateful Dead, would not take place until December of 1965, a full five months later.

“So we go downstairs,” Olsen continues, “get set up, and start playing. And nothing’s happening.” Which is to say, Olsen was feeling no effects from Unobsky’s acid-infused sugar cube. Not yet, anyway. “Somewhere in the first or second song, all of a sudden everything started to change. The room started doing different things, and we were just looking at each other, laughing. We began to trade instruments, ‘You play this, and I’ll play that,’ and sitting down on the stage. It was like, ‘Wha-at?’”

The two versions of the poster created by Mike Ferguson and George Hunter for the Charlatans’ 1965 shows at the Red Dog are both known as “The Seed” because the poster started the psychedelic-poster revolution that would flower the following year.

Somehow, the Charlatans got through their set, or something that approximated a set. “Mark was just giggling and laughing,” Olsen says. “He was a rotund guy, and a guitar player himself; he played blues and bottleneck guitar. And when he would laugh, his whole belly would just shake. And he came up to us afterwards and said, ‘That was the funniest thing I ever saw, you guys are hired!’”

In the end, the Charlatans would play six weeks at the Red Dog—four sets a night, six nights a week. For this, they were paid the princely sum of $600 per week in cash. “We each got 100 bucks, plus food, lodging, and acid,” Wilhelm jokes, “so who got the extra hundred?”

“Mark had been going to each person’s room, saying, ‘Here’s a little sugar cube.’”

“It felt like it lasted the whole summer,” Olsen says. In part, that may have been because a sizable portion of those six weeks was spent tripping on LSD, which was reportedly supplied to Unobsky by Owsley Stanley, yet another Angeleno who would have a profound impact on the San Francisco music scene (Owsley is best known for bankrolling the Grateful Dead with the money he was making manufacturing and selling LSD, both before and after the drug was made illegal).

Set lists of Charlatans shows at the Red Dog reveal a band hitting its stride, as each of its four musician members took turns in the spotlight. Wilhelm sang honky-tonk blues numbers like “32-20,” Ferguson covered Mose Allison’s jazzy rendition of Willie Dixon’s “Seventh Son,” Olsen was front-and-center for rock-‘n’-roll numbers like Chuck Berry’s “Carol,” while Dan Hicks, already chafing behind his drum set, stepped up to the microphone for “How Can I Miss You When You Won’t Go Away.” And every night, the whole band would tear it up on “Alabama Bound.”

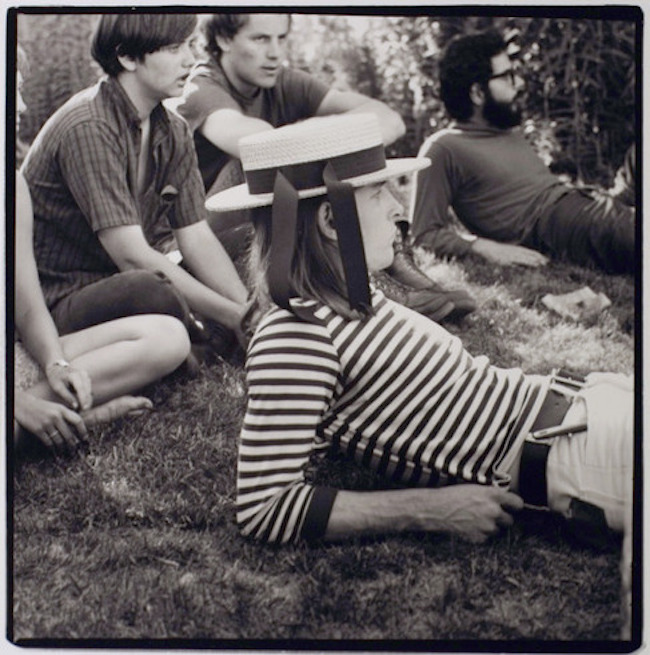

The Charlatans and some of their “old ladies,” photographed at the Palace of Fine Arts in San Francisco by Herb Greene. From left to right: Mike Ferguson, Dan Hicks, George Hunter, Lucy Lewis, Mike Wilhelm, Richard Olsen, Susan Pilborough, and Carmella “Candy” Storniola.

The band’s “old ladies,” as girlfriends were endearingly called in those days, wore lots of velvet and chiffon. “We all wore these cut velvet dresses and danced,” Lewis says. “I tried to get into it, but we were sort of like stage props.” But more important to Lewis than her attire was the sense of community she felt at the Red Dog. “Everyone was involved,” she says, “the people who ran the kitchen, the guys who were working on the place. We developed a special bond with each other that has lasted to this day. So yes, we dressed up like Victorian women and danced, but we also shared this life-changing experience, and were aware of how special it was, even at the time.”

From the vantage point of 2017, some of those experiences seem downright crazy. “On Sunday night, when we’re sort of winding up the last set for the evening, everybody would drop LSD and be up all night into Monday, when Mark and a few of the other guys at the saloon would drive out to this canyon to shoot rabbits,” Hunter says. “I joined in.”

“We decimated the rabbit population for seven years,” Olsen jokes. “There wasn’t a wild jack rabbit left.”

“You could not be up there and not have a gun,” Wilhelm says. “I went shooting rabbits a couple of times with Mark and those guys. They had shotguns, though, so the poor rabbits didn’t stand a chance. I used to bring my rifle—you had to be a good shot to tick off a rabbit with a rifle. I do like guns, and I like shooting, but I was never into killing things. It didn’t appeal to me.”

For Wilhelm, a more productive use of his Mondays was to drive to San Francisco to lay in supplies for the rest of the week. And as the summer was winding down, he made what would be his last such trip.

“Chandler and I had made a run down to San Francisco on our day off, basically to score some weed and acid. We had dropped some acid to stay awake for the trip back because we hadn’t gotten any sleep at all—Owsley’s acid always had a little bit of real high-quality methedrine in it—and we’re driving back through the East Bay when I notice that Chandler’s engine is overheating. So we pull off in the town of Rodeo, a notorious speed trap, and head for a gas station. And we’re there for no more than 10 minutes, and here comes a sheriff’s car.”

At first, the visit seemed friendly. “They walk over,” Wilhelm continues, “to find out who we are, but laying on the dashboard of Chandler’s car is his .32-20 Colt Police Positive, an old police pistol from turn of the century. One of the officers points at it and says, ‘Is that loaded?’ And Chandler says, ‘Yes, as a matter of fact it is.’ And the officer says, ‘May we see it, please?’ and Chandler hands it to him. They take the cartridges out, and kind of smile because it’s an old gun, and then hand the pistol and the cartridges back to him, so it wouldn’t be loaded.”

For this show at the Avalon in September of 1967, the Charlatans shared the bill with the great blues guitarist Buddy Guy. Poster by Robert Fried via ClassicPosters.com.

By this point, Wilhelm and Chandler are coming onto the acid, and time is beginning to stand still. “We proceed to tell them our whole life stories,” Wilhelm says, “about how we’ve been up at the Red Dog playing music, how we’re on our way back, and blah, blah, blah. This goes on for, oh, I don’t know, probably half an hour, but it seems like forever. Eventually, we’re running out of things to talk about so, in an attempt to end the conversation, Chandler turns and puts the radiator cap back on. And that’s when one of the cops spots the top of a vial sticking out of Chandler’s waistband, just the top. Next thing we know, we’re sprawled out against the car and they’re frisking us. They’ve found Chandler’s little vial of weed, and I had a joint in my vest pocket, but they never found our main stash.”

Now Chandler and Wilhelm are in cuffs, being hauled off to the county jail, and their arrest by Rodeo’s finest is promptly communicated to their counterparts in Virginia City—the Charlatans and the rest of the gang at the Red Dog found out about the bust when it came over the teletype at the “Territorial Enterprise,” the town’s historic newspaper. “The cops up in Virginia City had been very mellow with us all summer,” Wilhelm says, “but suddenly they had to take a stand: ‘Oh, you guys had drugs?’ They’d known we had drugs the whole time, but because we weren’t turning on the local teenagers or bothering anybody, they didn’t care. But now they had to do something, so they planted some venison in the refrigerator of the Red Dog, and then bust the Red Dog for poaching! That’s the way they handled it. Meanwhile, we make bail. By the time we get back up there, the vibe is pretty weird. It was probably time to get out of Dodge anyway, and then the bus shows up.”

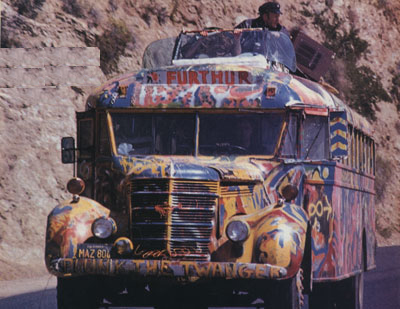

As in the “Furthur” bus, which, in 1964, had been famously driven across the United States, with Ken Kesey and the Merry Pranksters on board. Neal Cassady—the model for the Dean Moriarty character in author Jack Kerouac’s “On the Road,” as well as “Cowboy Neal” in a Grateful Dead song—was behind the wheel.

This was hardly the first time people had journeyed to Virginia City to see what the Charlatans were up to at the Red Dog. “In the beginning, there were a lot of locals and tourists in our audiences,” Olsen says, “but word of mouth spread quickly. People started coming from San Francisco, Seattle, Oregon. One time, we had about 50 Hells Angels on motorcycles come through, and the governor of Nevada showed up twice, the second time with his family. Every weekend it was something different.”

Which is to say, the Charlatans were not overly impressed by the arrival of Kesey and company—they were more concerned with the fact that their lead guitarist had just been arrested.

“My understanding was that they had somehow heard about us and had decided to check us out,” Olsen says. “I liked Neal Cassady. He was pretty whacked, but a funny guy. He would talk and talk, just to make you laugh. He was on the bus when it was parked in front of the Red Dog and I climbed aboard, but I didn’t talk to any of the Pranksters. I don’t think we were on the same sort of trip. They were more into a purist’s psychedelic experience trip. We were into Old West.”

“Those guys were heavily into mind-fuck games,” Wilhelm says of the Pranksters. “And here we were, a bunch of acid heads carrying loaded guns, armed to the teeth. This terrified them. Once they got a good look at us, man, like, 20 minutes later, they were on their way out of town.”

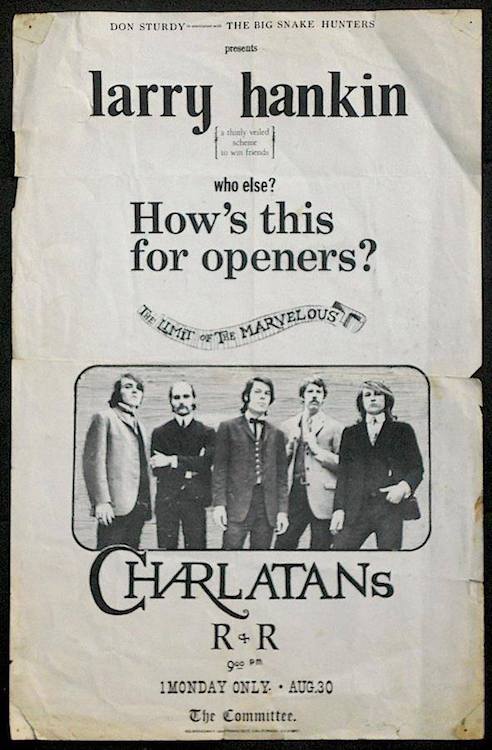

The night after their last show at the Red Dog, the Charlatans played their first gig in San Francisco, opening for Larry Hankin of a comedy group called The Committee. The “Don Sturdy” who’s listed at the top of the poster is better known by his real name, Howard Hesseman—he hired Mike Wilhelm for his first paying gig in San Francisco at the Coffee Gallery in 1963.

And so, the Charlatans’ historic six-week run at the Red Dog Saloon in Virginia City, Nevada, came to an abrupt end. Wilhelm would avoid jail time, but now he had a record, which would come back to haunt the band a couple of years later. In the meantime, the Charlatans were rehearsed and tight, ready to ride the momentum. Which is why the night after their last performance at the Red Dog, the Charlatans were playing in San Francisco, opening for a one-man show starring a friend of the band’s, Larry Hankin of The Committee.

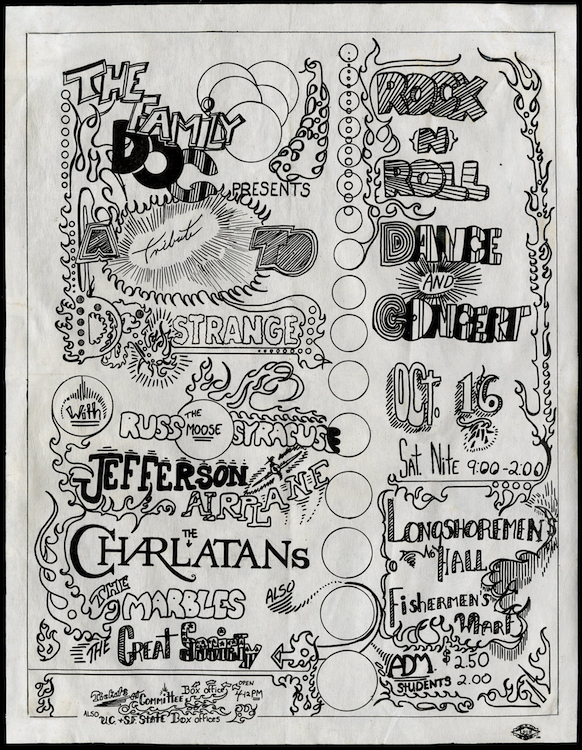

More gigs would follow that fall at the Matrix, a new club on Fillmore Street opened by Marty Balin of Jefferson Airplane, and at Longshoremen’s Hall, which was rented for three concerts in October by Luria Castell, Ellen Harmon, Alton Kelley, and Jack Towle, who called themselves the Family Dog. Castell and company had been at the Red Dog, too, dining on Unobsky’s food and dropping his acid while helping Chandler Laughlin run things. As fate would have it, they now all found themselves renting rooms in a boarding house on Pine Street, one of several managed by Bill Ham, who had provided the light-show machine for the Charlatans’ run at the Red Dog. Hunter and Lewis had moved there too, making Pine Street the center of San Francisco’s burgeoning hippie scene.

The three shows at Longshoremen’s Hall in October of 1965 are considered watersheds in San Francisco rock history, not least because they preceded the more famous Trips Festival in late January of 1966, which was also held at the hall, by three full months. Each of the Family Dog’s October concerts featured the Charlatans, but people also attended those shows to see Jefferson Airplane, the Lovin’ Spoonful, and the Mothers.

In October of 1965, the Family Dog produced three shows at Longshoremen’s Hall. Each was promoted as a “tribute” to various comic-book characters, and each featured the Charlatans on the bill. Via ClassicPosters.com.

“When we went to Virginia City, there wasn’t another band on the San Francisco scene,” Hunter says. “When we got back, everything had just sort of blossomed. At the time, you could sense a cultural revolution was starting to take place, but it was hard to pin it down. When I look back on it now, I can’t believe how fast everything happened.”

By the beginning of 1966, the speed was breakneck. “Instead of just five bands who wanted to play, now there were 20 or 30, coming from cities like Seattle, from Texas, and from other places,” Olsen says.

If it sounds like the mellow psychedelic hippie music scene of ’60s San Francisco was becoming uncharacteristically competitive, well, it was. “We all knew each other and we were all friendly,” Olsen says, “but it wasn’t like we hung out together, except on special occasions or at shows. So there was a sense of competition. If one band was doing a show, there was actual jealousy because another band had probably wanted that gig. Everyone wanted to be the band.”

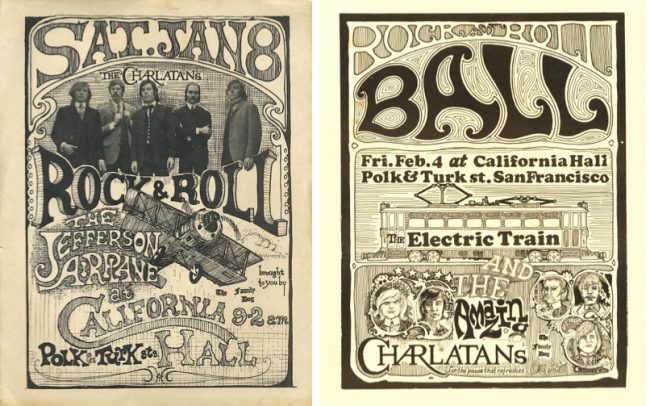

Potentially, any of the bands on the scene stood in the way of Hunter’s dream of turning the Charlatans into the American Beatles. So, in partnership with the Family Dog and Rock Scully—who would soon become one of the Grateful Dead’s managers—Hunter produced a pair of Charlatans shows at California Hall. The Charlatans headlined the first date on January 8, with Jefferson Airplane as the opening act. On that night, the place had been packed, thanks, as Hunter would learn at the second California Hall show, to the Airplane’s exploding fan base.

Along with the Family Dog and future Grateful Dead manager Rock Scully, George Hunter produced a pair of shows in early 1966 at California Hall. The first one with Jefferson Airplane was a huge success, but the second with Electric train was a bust. Hunter designed the first and collaborated with bandmate Ferguson on the second. Both via ClassicPosters.com.

“I think it was Marty Balin who mentioned something to me at California Hall about getting into some kind of partnership,” Hunter says. “I wasn’t too keen on that, though. I thought, ‘What do I need Jefferson Airplane for?’ Well, I found out when we did the second California Hall show, and it was a total bust. I figured Electric Train, Jefferson Airplane—they’re all the same. That was the end of my career as a producer.”

In fact, on the same night, February 4, that the Charlatans opened for Electric Train at California Hall, Jefferson Airplane was headlining Bill Graham’s first non-benefit concert at the Fillmore Auditorium. The Airplane would also take top billing a few weeks later when the newly re-organized Family Dog, now being run by Hunter’s old friend Chet Helms, produced its first concert, also at the Fillmore. Despite having been first out of the starting gates, the Charlatans were already playing catch up.

Which finally brings us back to Rancho Olompali. In May and June of 1966, or thereabouts, the old estate was being rented by the Grateful Dead, which was quickly becoming the band. There, the competition for gigs at Bill Graham’s Fillmore and the Family Dog’s new home, the Avalon Ballroom, could momentarily give way to the thing that had lured everyone to the scene in the first place—music.

“I remember playing guitar by the pool at a party out there at Olompali, a big acid party,” Wilhelm says. “Jerry Garcia heard me playing this song, ‘500 Miles,’ which has a rhythm part that sounds like a train. He says to me, ‘What’s that lick you’re playing there? Show me that.’ So I slowed it down and showed it to him, and lo and behold, for the next three years, it’s the high point of every solo he does. To this day, if I play that song, somebody will say, ‘Oh, man, that’s a Jerry Garcia lick.’ It’s the other way around.” Years later, though, when rock photographer Herb Greene asked Garcia to name his favorite guitarist on the San Francisco scene, the Dead’s lead guitarist replied without hesitation, “Mike Wilhelm.”

It was on the same day that George Hunter did not aim his rifle at Jerry Garcia.

“The Dead had just moved into Rancho Olompali,” Olsen recalls. Members of the Charlatans, along with numerous other singers, guitarists, drummers, and keyboard players in San Francisco’s new rock royalty, had been invited to a party at the band’s new digs.

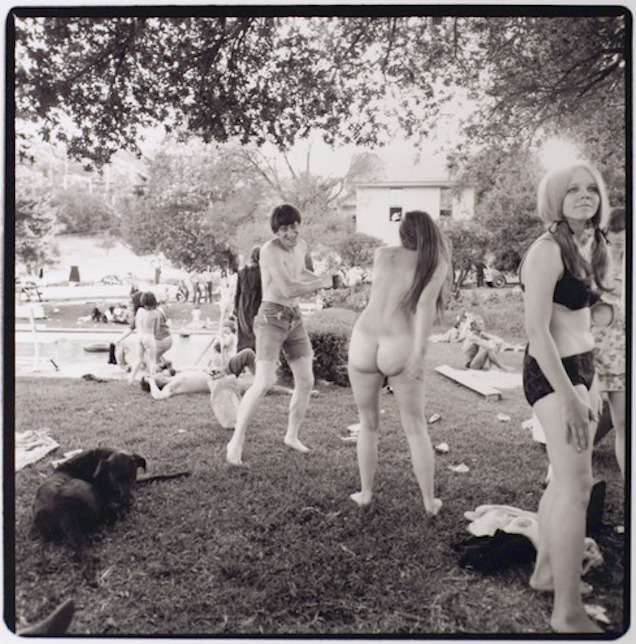

“It was a hot day,” Susan Olsen says, picking up the story from her husband—at the time she was Susan Pilborough. “I remember half the people had their clothes off, walking around naked, swimming in the pool. It was amazing. And for some reason,” she adds, “George had his gun with him.”

Yes, the same rifle Hunter had picked up in Virginia City, where he often went shooting under the considerable influence of psychedelics. Today, the idea of bringing a loaded weapon to a party while high on drugs would probably strike most people as a recipe for disaster, but at the time, for Hunter, it didn’t seem radically out of the ordinary.

In fact, Hunter was not the only one packing heat for fun that day. “There were people shooting back in the hills somewhere,” Wilhelm says, “away from the house. I didn’t go back there, but I could hear these little pops from .22s every now and then. When George went back there with his .30-30 Winchester Carbine, I heard this huge blast, a very loud echoing report.”

“We had walked out toward the back of the property,” Susan Olsen says, “which was this serene setting with oak trees and grass.” That’s when Hunter had fired his rifle. “It made this big boom. All these naked people in the hills started popping up out of the grass, going, ‘Don’t shoot! Don’t shoot!’ It was the most bizarre thing.”

“At one point, I’d gone out to the fringes of the party and shot at something on the hillside,” Hunter says. “I had a pretty clear view, but after I fired my gun, I remember some people had jumped up out of the bushes. Well, that didn’t seem very good. So I decided I wasn’t going to shoot there anymore.”

“When he came back,” Wilhelm remembers, “George was carrying his rifle, talking about how exciting guns were. ‘It’s that element of danger,’ he was saying.”

And it was on the way back from the serene setting where Hunter had fired his rifle that he and Susan and Richard ran into Jerry Garcia, who stopped to chat. “I said, ‘How would you like to be looking down the barrel of this thing?’” Hunter recalls. “It was not in the context of a threat. It was just a hypothetical question—that it would be an uncomfortable position to be in. It wasn’t like I intended to put him in that position.”

At this point, Garcia didn’t seem especially upset by what Hunter was saying to him. “We were having a little conversation,” Susan Olsen continues, “and then, suddenly, George says to Jerry, ‘I’d hate to be in your shoes right now, man.’ And then he makes this little, ‘Heh, heh, heh’ laugh, which was so George. I thought he was making some sort of reference to Jerry and his band, I didn’t think it was threat from George, but Garcia must have been high on acid, because he got this look of terror on his face and went, ‘Ahh!’ and just jumped back and started running away. At the time, it was funny.”

Soon, though, things got decidedly unfunny. “Something tripped in my head,” Hunter says, “and I started thinking that I had shot somebody, and I started to lose it. I left with Richard and Sue and Lucy shortly after that.”

“George was loaded on acid,” Richard Olsen says, “and he started going on a weird trip that he’d shot somebody. He couldn’t come down. He got stuck on that.”

“We had a little cabin out at Muir Beach,” Susan Olsen says, “so George and Lucy came back to stay with us. It was a one-room cabin, so it was pretty tight. And all night long, George was going on and on, just moaning. He thought he’d killed somebody.”

“Then I heard a news report on the radio, something totally unrelated except that it had to do with somebody being shot,” Hunter says. “Immediately, I added that into the framework in my mind.”

“It took us all night to convince him that everything was OK,” Susan Olsen says, “like 12 hours.”

Using a Herb Greene photo, Hunter designed this ad to announce the Charlatans’ first single on Kama Sutra, but the label had second thoughts, and it was never released.

At the time of the Incident at Olompali, the Charlatans had one thing going for them that most other San Francisco bands didn’t—a recording contract with Kama Sutra Records. Had the Charlatans been able to release an album in, say, the fall of 1966, that would have put them in the same club as Jefferson Airplane, whose debut album for RCA dropped in August of 1966, and the Grateful Dead, whose eponymous first LP for Warner Bros. hit record stores in March of 1967. It was not to be.

“We had this crummy record deal that we signed in our kitchen, with no lawyer present,” Olsen says. “It had no guarantee of release. We’d be playing the Avalon, and everybody would be going, ‘When’s your record coming out?’ And then all of a sudden we heard that the Airplane had just signed with blah, blah, blah, that the Dead had signed, and our record was still not coming out. It was like we’d been at the top of the stack, and now we were getting lower and lower because everybody was moving in on our territory, so to speak.”

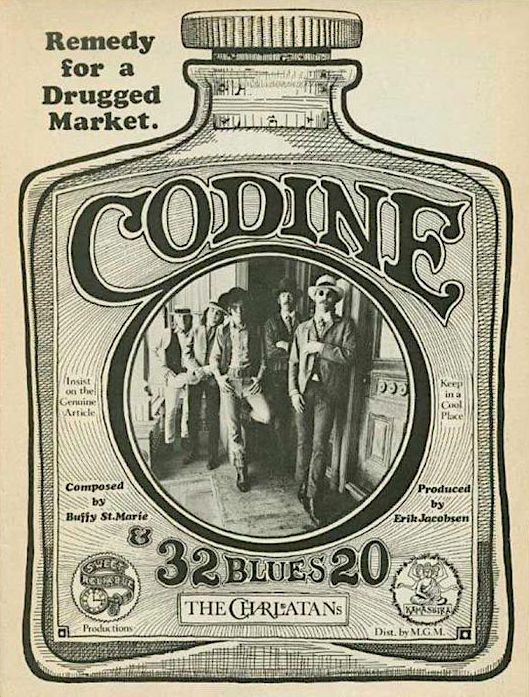

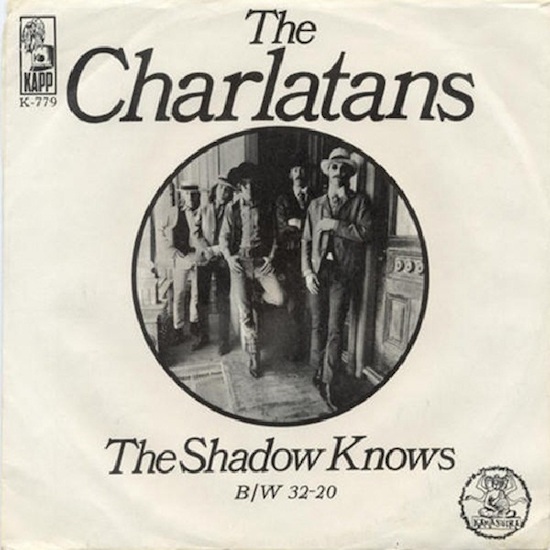

To this day, none of the surviving Charlatans know for sure exactly why Kama Sutra balked at releasing their album. The problems began with the choice for its first single, produced by Lovin’ Spoonful producer Erik Jacobsen—a cover of a 1963 Buffy Sainte-Marie song called “Cod’ine,” with the Charlatans’ version of bluesman Robert Johnson’s “32-20” as the B-side.

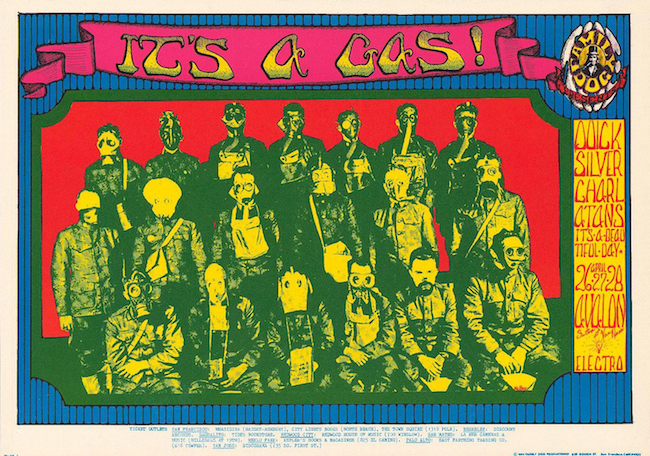

The Charlatans shared the bill with Quicksilver Messenger Service on numerous occasions. This poster from April 1968 is by Alton Kelley. Via ClassicPosters.com.

“We were like, ‘Wow, this is going to be so hip, a Buffy Sainte-Marie on one side and Robert Johnson on the other,” Wilhelm says. “It would have caught the attention of the folk music crowd, like when the Animals released their cover of ‘House of the Rising Sun.’ It would have been so cool.”

“George designed an ad for the single that was going to run in ‘Billboard,’” Olsen says. “But the record company said, ‘This is a song about drugs, we can’t release that.’ Well, ‘Cod’ine’ is actually an anti-drug song. I think we would’ve taken off with that record.”

Indeed, within a few months of “Cod’ine” being pulled, in the spring of 1967, Jefferson Airplane had a huge hit with “White Rabbit,” which was a pro-drug song, so the idea that a song about drugs could offend the delicate sensibilities of a record company looking to make a fast buck seemed a bit hard to swallow to the Charlatans. But according to Erik Jacobsen, that was exactly the concern of the people who ran Kama Sutra Records. “They thought it was an OK song,” he says, “but it didn’t sound like a hit to them, so they didn’t want to put it out. And yes, I think they also thought it was too much of a druggie song.”

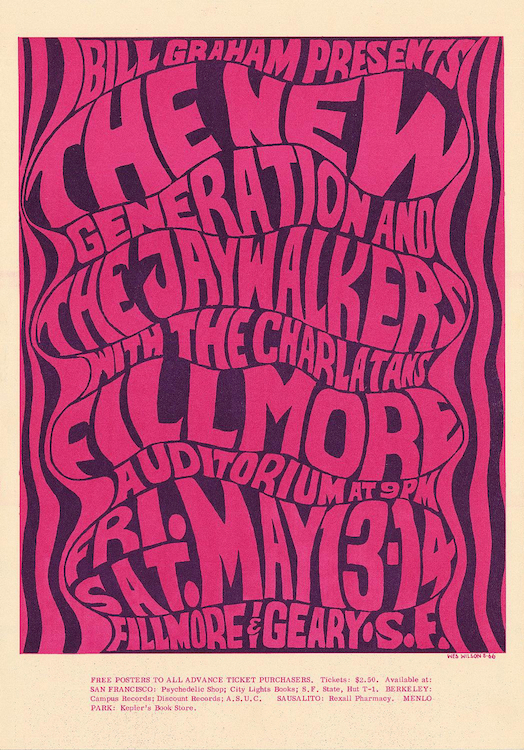

This early Wes Wilson poster from 1966 for a Family Dog show at the Fillmore includes Hunter’s Charlatans logo. Via ClassicPosters.com.

Over the years, Hunter and Olsen have wondered if it may have been more than the song’s content that killed their first 45. “The Lovin’ Spoonful had an autoharp; we had an autoharp,” Olsen says. “They played sort of old-timey stuff; that’s what we did.” Could it have been that Kama Sutra was secretly concerned about the impact the Charlatans’ success might have had on its golden goose, the Lovin’ Spoonful?

“In their dreams,” Jacobsen says, laughing. “Listen, I’ve been friends with those guys for years, and I’m really glad we gave it a shot, but as far as I know, that is absolutely not the case.” The problem with the Charlatans, Jacobsen says, was simple—the drug reference aside, they did not have a hit-maker like John Sebastian in their band. By the summer of 1966, Sebastian had written “Do You Believe In Magic,” “Daydream,” “Did You Ever Have To Make Up Your Mind,” and “Summer in the City,” which reached No. 1 on the “Billboard” pop charts.

After their “Cod’ine” single was killed by Kama Sutra Records, the Charlatans released a novelty tune called “The Shadow Knows” with Kapp. Not surprisingly, the 45 went nowhere.

After their “Cod’ine” single was killed by Kama Sutra Records, the Charlatans released a novelty tune called “The Shadow Knows” with Kapp. Not surprisingly, the 45 went nowhere.

Instead of releasing “Cod’ine,” Kama Sutra handed the Charlatans and its Jacobsen-produced recordings over to Kapp Records—Jacobsen stayed on as the band’s producer. “Erik came back and told us he had this great idea for a tune that we should do,” Hunter says, “and that we could put it out as a single. It was a novelty tune from the ’50s by the Coasters called ‘The Shadow Knows.’ I don’t know how we could have been so docile to just stand there and let him talk us into that, but we did. It didn’t stand a snowball’s chance in hell going anywhere.” And, it didn’t.

“At that time, I was working with Sopwith Camel, Tim Hardin, and the Lovin’ Spoonful,” Jacobsen says, “so it was kind of a whirlwind period for me. So I don’t really know where ‘The Shadow Knows’ came from, but they recorded it.”

Although there were lots of places to see music in San Francisco in the late 1960s, the Fillmore and the Avalon were the two main dance halls. At left, Jerry Garcia performing at the Fillmore with the Grateful Dead in 1968. At right, Bo Diddley performing at the Avalon in 1967. Both photos by Steve Fitch.

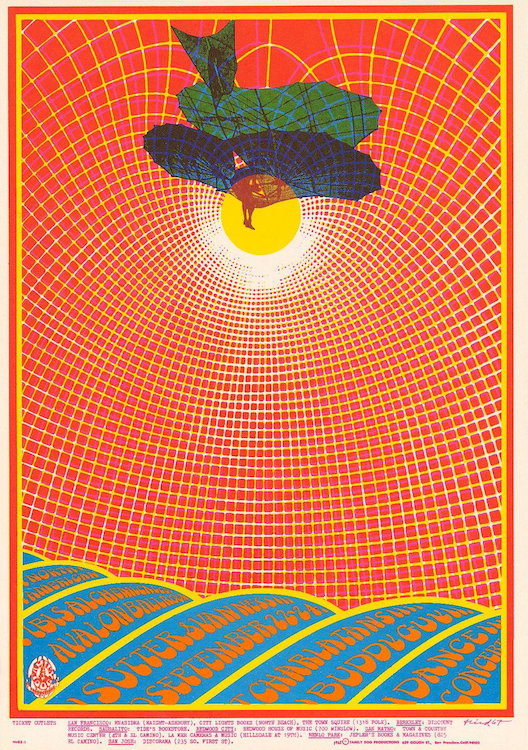

By 1967, with the prospect of a hit record looking dimmer and dimmer, the Charlatans spent a lot of their time performing live at the Fillmore Auditorium and Winterland, which were run by Bill Graham, and the Avalon Ballroom, which was run by Chet Helms and the Family Dog. The Charlatans played all three venues regularly, but the Avalon always felt like home.

“The Avalon was more like ‘your people,’” Olsen says, “you know what I mean? It was a scene. The Fillmore was a gig. There’d be a lot of people there who you knew, but it was more business-like. It was fun being in the audience, but as a band member, I didn’t think it was as much fun as playing at the Avalon.”

San Francisco’s main music impresarios: At left, Chet Helms of the Family Dog. At right, Bill Graham. Both photos are circa 1966 and by Herb Greene.

Wilhelm agrees. “The Avalon was so much better as a venue. It had a spring-mounted dance floor, which all the old ballrooms had, and the stage was in the corner of the room, which meant that the light show was spread out a full 180 degrees across two walls, with the stage in between. There wasn’t even any stage lighting; they just used the light show to light the stage. People would be out there dancing, surrounded by the light show. It was a fantastic setting.”

As they did with their wardrobe and graphics, the Charlatans customized this visual aspect of the dance-hall scene. “We didn’t want to be identified with the light shows,” Hunter says. “It didn’t reinforce our image.” “We got around that,” Wilhelm says, “because Herb Greene shot a bunch of color slides of us in Golden Gate Park and at other locations like the Balclutha. These were projected as a part of the light show. They looked especially impressive at the Avalon because they were projected floor to ceiling. I’m sure it pissed off some of the bands who must have asked themselves, ‘How come we didn’t think of that?’”

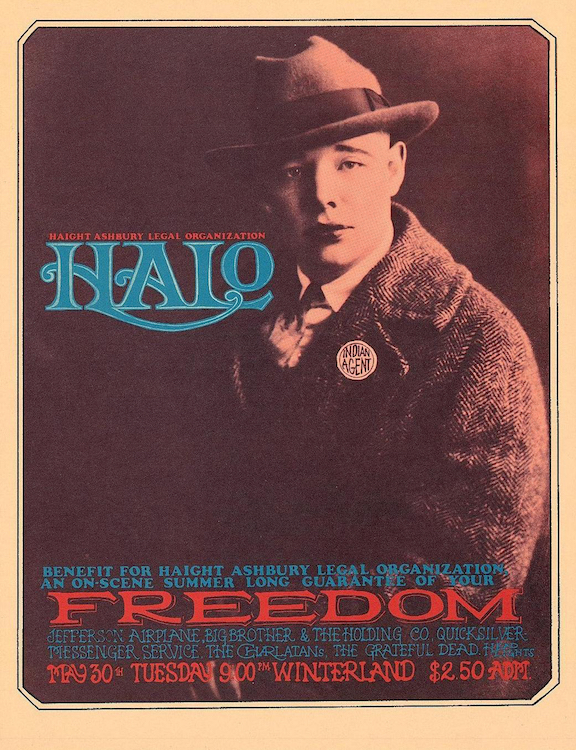

Compared to Chet Helms at the Avalon, Bill Graham ran a tight ship. In one famous story, the Charlatans were not allowed to take the stage at Winterland one night because Mike Ferguson had gone home to change his pants, causing the band to be late. “It was the HALO benefit,” Olsen says of the show for the Haight-Ashbury Legal Organization, which represented musicians and others arrested for drugs. “All of the five original bands were there, the Airplane, the Dead, Big Brother, Quicksilver, and us. We were supposed to go on first, but when Ferguson didn’t show up at 8 p.m., Graham had us take all of our equipment off the stage. It was disappointing, and embarrassing.”

In contrast, all kinds of crazy shit happened at the Avalon. For example, there was the time Quicksilver’s lead guitarist, John Cipollina, brought his pet wolf to a show and wanted to keep it in the dressing room. “I didn’t think that was such a good idea,” Wilhelm says, who was on the bill that night with the Charlatans, and was concerned for the animal’s well being while Cipollina was performing on stage. “It was too frantic a scene in there, all these strangers wandering around, and the wolf was very nervous and paranoid. I wound up sitting with her, trying to keep her calm, and told John after his set that he had to get her out of there. It wasn’t good for the animal, and something bad could have happened.”

And then, of course, there were the Hells Angels. “The Hells Angels would come to shows at the Avalon every now and then,” Olsen says. “One night, they had an initiate with them. His initiation rite was to sing with the band, which was us. We were playing, and the Angels just came up on stage and said, ‘This guy’s going to sing with you. You’re going to back him, and you’d better be good.’ We played a blues tune, or something like that. The Angels all wore the same engineer boots, and they were sitting behind our amps, so I remember seeing all these engineer boots sticking out and thinking, ‘Oh, man, I don’t want to do this anymore.’”

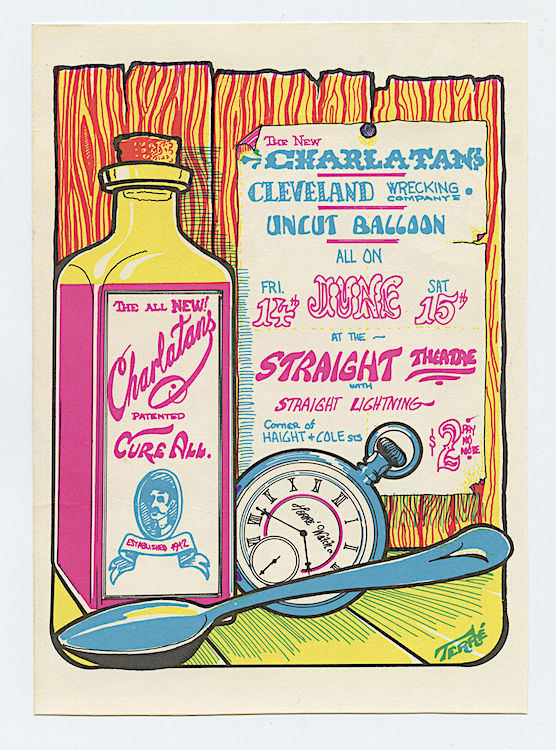

Along with the Grateful Dead, Country Joe & the Fish, Quicksilver Messenger Service, and Big Brother and the Holding Company, the Charlatans played the opening of the Straight Theater on Haight Street during the Summer of Love. Poster by Frank Melton via ClassicPosters.com.

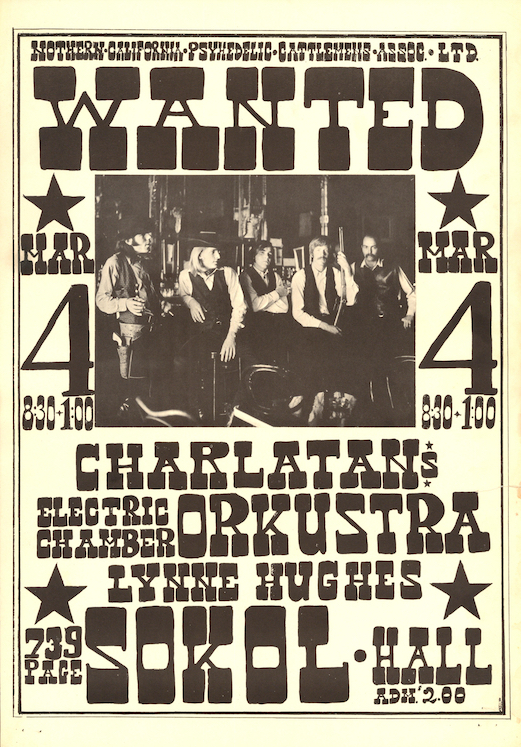

In addition to playing the Fillmore and Avalon, the Charlatans were booked at the Matrix, Western Front, the Straight Theater, the Firehouse, Sokol Hall, the Ark in Sausalito, Harmon Gym over in Berkeley, and a tavern out at Muir Beach. Lots of other bands on the psychedelic music scene in the first half of 1967 played those places too, but only the Charlatans decided to also spend six weeks performing at a strip joint on Montgomery Street.

Richard Olsen had finally made it to North Beach, although probably not in the way he would have thought when he and his clarinet arrived at San Francisco State.

In hindsight, the band’s run in March and April of 1967 at Varni’s Roaring Twenties was a bookend to its residency at the Red Dog. Both periods were soaked in drugs—a psychedelic substance called DMT was the stimulant of choice at Varni’s—both lasted about six weeks, and both included four or five shows a night, five or six nights a week.

“It was the perfect venue,” Hunter says. “We already had the outfits.” “And,” Olsen adds, “there were three topless women on different stages at all times.”

This poster by George Hunter and Nathan Terre, who was the Charlatans’ manager for a short period of time, was created toward the end of the band’s spring 1967 residency at Varni’s Roaring Twenties, an upscale strip joint in North Beach, but it was never used because the band was either fired for not playing a cover of “Winchester Cathedral” or quit when the club owner refused to pay them a union rate—or both.

Varni’s obviously catered to a different crowd than the Fillmore and Avalon. “It was primarily tourists,” Hunter says. “It wasn’t a hippie place,” Olsen adds. “People would be in suits, that kind of thing. The club was downstairs and looked like a high-class whorehouse, with lots of velvet and dark hardwood. It had a big bar and a stage in the back. One girl would dance on the bar, a couple more on other small stages, and then every half hour we’d play ‘Sweet Lorraine’ and a girl on a swing, with nothing on except her crossed legs, would rise out of the floor. We’d do the tune, she’d swing, and then she’d go back down.”

“It was like a carryover from the Red Dog,” Richard Olsen says. “It had a bar, bentwood chairs, Tiffany-style stained-glass chandeliers, red-flocked wallpaper, that old-fashioned vibe—it was very old North Beach.”

“That place was fun!” Susan Olsen says. “It wasn’t sleazy like some of the places in North Beach; it was kind of classy. And the women were great dancers. I remember one woman, who I think had come from Las Vegas. She was a statuesque stripper. I had never seen anything like that. It was so classic and provocative, yet elegant, too. Yeah, that place was amazing.”

A rare East Bay gig for the Charlatans, with Country Joe & the Fish, in 1966. Poster by Stanley Mouse and Alton Kelley, via Psychedelic Art Exchange.

“It was also right around the corner from the Playboy Club,” Wilhelm says of Hugh Hefner’s San Francisco outpost, “where Vince Guaraldi was playing. He wandered into Varni’s one night, I guess on his break. He noticed we had an electric piano that was an actual piano with magnetic pickups in it, like on an electric guitar. He liked the sound of that instrument and asked if he could sit in. We went, ‘Vince Guaraldi? Sure, come on, man.’ So he would come over on his breaks and play with us.”

Varni’s, though, was also exhausting. “It was fun, but it got old real fast” Wilhelm says. “We’d be on our break, and it’d be time for us to go on. The manager would come into our dressing room upstairs, and we’d all be lying on the floor, stoned on DMT. He’d get us up, we’d go downstairs, and I’d look down the neck of my guitar, and it seemed 20 feet long. But we were so dialed in from performing every night that we played just fine no matter how out of it we were.”

This Family Dog poster from 1967 was a collaboration between George Hunter and poster artist Rick Griffin, with a Herb Greene photograph as the main image. Via ClassicPosters.com.

Two reasons are given for why the Charlatans’ run at Varni’s ended. “Bill Varni wanted us to play a cover of ‘Winchester Cathedral’ during our act.” At the time, the ’20s-sounding song by The New Vaudeville Band was an enormous hit. With their straw-hat skimmers and Edwardian threads, the Charlatans looked the part, and the song would have been perfect for a place called Roaring Twenties. “Yeah,” Hunter agrees, “it would’ve been perfect, but I said, ‘No, we don’t do covers.’” Which, of course, was not totally true since the band’s first single was a cover, but it seems to have been a point of principle for Hunter, if not something he communicated to the rest of the band.

“Why did we lose the gig?” Richard Olsen asked George Hunter during one of our conversations. “Because we didn’t do ‘Winchester Cathedral,’” Hunter replied. “Oh, is that the reason?” Olsen said. “Yes,” Hunter answered, “Mr. Varni was not happy.”

“I thought it was mainly over money,” Wilhelm says. “We were tired of playing there anyway, so George asked him for more money, which I think we knew they weren’t going to give us. We were playing under a union contract, but we had to kick back some of our fee to them. They weren’t even paying us scale. So when we asked for more money, all we asked for was the full union rate. They wouldn’t give it to us, so we left.”

By this time, May of 1967, the hype accompanying the upcoming Summer of Love was in full flower. “The rest of the country was trying to co-opt the scene in San Francisco,” Hunter says. “By the time Summer of Love actually came around, there were all these people showing up who had no business being there—kids, primarily, and the people exploiting them. It was no longer a scene enjoyed by a relatively small bunch of hip people. All of a sudden, we were inundated.”

The weekend of the Monterey International Pop Festival, which kicked off the Summer of Love in 1967, the Charlatans were playing in a bowling alley for a high-school dance, and got arrested for possession of marijuana.

According to Hunter, the change was not necessarily apparent in the places like the Fillmore and Avalon, where everyone was there for essentially the same reasons—to get high, socialize, listen to music, enjoy the lights, and dance. “The environment inside the dance halls sort of shaped that culture,” he says. “But outside, things were much less contained. The connection between the dance halls and the street scene wasn’t that strong. On the street, music wasn’t the overriding factor.”

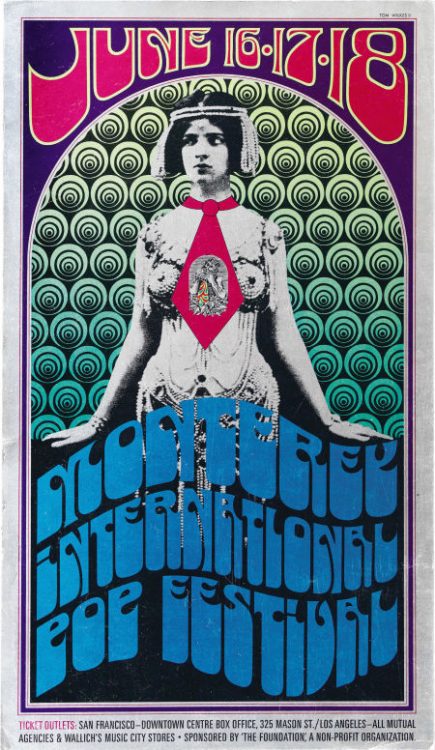

That said, psychedelic rock music was the soundtrack for the Summer of Love, whose blockbuster—to continue the clichéd movie-biz analogy—was Monterey Pop, which ran from June 16 to 18 at a fairground a few hours south of San Francisco. Naturally, the San Francisco Bay Area was well represented. Big Brother and the Holding Company was there (the band actually played two sets because Janis Joplin was pissed off that their first set had not been filmed), as was Quicksilver Messenger Service, Country Joe and the Fish, Moby Grape, the Electric Flag, Steve Miller Band, Jefferson Airplane, and the Grateful Dead, whose set was sandwiched between performances by the Who and Jimi Hendrix.

Of the San Francisco groups not invited to Monterey Pop, the Charlatans were the most glaring omission. They could have attended anyway, probably getting back stage to rub elbows with Ravi Shankar, Brian Jones of the Rolling Stones, and Otis Redding. Instead, the band found itself playing yet another crappy gig—and getting arrested for its trouble.

“George had booked us to do a high school dance in San Jose,” Wilhelm says. “It was somewhere down the Peninsula at a bowling alley,” Olsen recalls. The gig was such a yawn that the band’s piano player, Mike Ferguson, decided he had better things to do. “Mike had a jacket that I decided to wear that night.” Olsen continues. “He always carried 10 or 12 joints in its outside breast pocket.” What could possibly go wrong?

“So we’re out in the parking lot, taking a break between sets,” Wilhelm says, “smoking a joint in George’s Volkswagen van.” “The whole van is full of smoke,” Olsen says, “and these security guys come out and knock on the door.” The van door opens, smoke pours out, words are exchanged, and the security guy goes off to find a police officer. “Meanwhile,” Wilhelm continues, “we’ve eaten all of the joints we had, kind of rolled them up in little balls in our mouths, soaked them with spit, and swallowed them, so that when the cops finally arrive there won’t be any evidence. But when the cops show up, they say, ‘You guys are all under arrest.’ I say, ‘Well, you don’t have any evidence.’ And they say, ‘Oh, we’ll find some.’ That was good and ominous.”

“Of the San Francisco groups not invited to Monterey Pop, the Charlatans were the most glaring omission.”

Upon being booked into a San Jose jail, the band members were forced to take off all their clothes, which the police vacuumed for evidence. Now, anyone who has rolled a joint knows that they are not exactly hermetically sealed containers, which means there was probably about a joint’s worth of marijuana wedged into the seams of Ferguson’s jacket. “They found enough pot in the breast pocket alone to charge us all with felonies,” Olsen says. Wilhelm remembers one line of their spirited, if futile, defense: “We’re all, ‘Hey, man, we buy our clothes in thrift stores. Who knows what’s in them?’” Needless to say, that argument did not fly.

A year of court appearances in San Jose, with representation by noted rock attorney Michael Stepanian, came down to one question: Who was going to take the rap? “It was between George and Wilhelm and me,” Olsen says. “Somehow Dan had snuck out of the whole thing, while Mike already had a felony because of his arrest with Chandler Laughlin.” “The law for weed was the same as the law for heroin,” Wilhelm says. “A second conviction for me would have meant a mandatory two years in San Quentin.” Since Olsen had been wearing the jacket, and Hunter was apparently never an option, Olsen agreed to take the fall. It did not involve jail time, but expunging the felony from his record took years, as did paying off the legal bill.

In hindsight, the ill-fated weekend of Monterey Pop, combined with the decision by Kama Sutra not to release “Cod’ine,” was the one-two punch that would eventually put the Charlatans on the canvas. Mike Ferguson was the first to go, playing his last show with the band on October 30, 1967, at the Matrix. “When you’re just going and going, and you’re not making any money, and you know that if something good like a record happened you’d be at another level, it’s frustrating,” Olsen says.

Not to put too fine a point on it, but during their years as the Charlatans, Hunter, Olsen, Wilhelm, Ferguson, and Hicks were perennially broke. “We weren’t exactly rolling in dough,” Hunter says. “I remember Mike Wilhelm talking one time about how many different ways we knew how to fix potatoes.”

For the Charlatans, economic and artistic frustration often expressed itself in fist fights, and not just off stage. “Yeah, there were a couple of good fights on stage,” Olsen says. “One time we were playing some college, and Dan just got up from behind the drums and started chasing George around the stage.” Another time, Hicks and Ferguson got in a fight on stage at the Avalon, and then there was the night when Ferguson just up and left the stage in the middle of a gig.

“They didn’t get along and couldn’t resolve their conflicts, and that took a lot of the energy out of the music,” Lucy Lewis says.

“There was a lot of weird politics within the band,” Wilhelm says. “It used to drive me nuts. The only reason I stuck around was because of the music. In fact, I think that’s the only reason any of us stuck around. We had horrible arguments and fights all time. It was just pretty darn miserable. But the music was amazing, and it kept us together.”

To fill the void left at the piano, as well as to give Hicks the chance to get out from behind the drums and sing a few more of the songs he was writing, the Charlatans added Patrick Gogerty to the band, a piano player Hicks had heard playing in a Shakey’s Pizza Parlor in Los Angeles. “He was quite a good ragtime player,” Wilhelm says. “Dan also turned us onto a superb drummer named Terry Wilson. All the time Dan was in the band,” Wilhelm adds, “he never bought a guitar. He always used my electric, 6-string Gretsch.”

“From my perspective,” Olsen says, “when Dan was the drummer and we were doing ‘Alabama Bound’ and ‘Cod’ine,’ that was the group, not when he was playing a guitar and doing his own tunes with the Charlatans. I didn’t think that was particularly who we were. If he was playing drums and wasn’t into it, he’d just screw up the beat and do all kinds of shit.”

This second incarnation of the Charlatans lasted barely six months, coming to an end on April 14, 1968, in Vancouver, B.C. There, Hicks and Gogerty played their last gigs, as did Hunter, whose leadership, or lack thereof, had finally become too much for Olsen and Wilhelm.

“I think our biggest problem, the thing that really screwed us, was that we never really had a good manager,” Olsen says. “We never had anyone who would take us to the next level, who would get us gigs and tell us what we needed to do to be successful. George always wanted to make those sorts of decisions. Nobody was ever good enough or hip enough for us.”

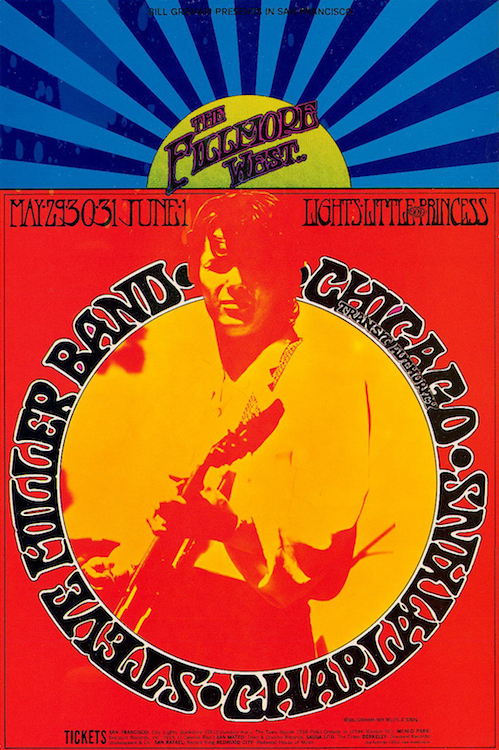

One of the Charlatans’ last performances was at the Fillmore West in 1969. Poster by Randy Tuten via ClassicPosters.com.

How well-developed was their sense of hubris? Well, fairly early on, the Charlatans passed on the opportunity to be managed by Bob Cavallo, who was managing the Lovin’ Spoonful and later went on to manage Earth, Wind & Fire. “He offered to be our manager,” Olsen says, “and we just snubbed him. We already had the mentality of rock stars. He turned out to be a very powerful guy in the music business. To me, that was a critical error. But George wanted to be the guy pushing the buttons, the guy making the decisions, good or bad.”

Erik Jacobsen isn’t so sure management by Cavallo was a foregone conclusion. “Bob was my partner,” Jacobsen says. “I think it was probably a mutual turn-down. They were in San Francisco, he was in New York, and I don’t think he was really that knocked out by the group or its potential. He was also pretty straitlaced. He’d been a club owner, and circulated in an arena that was definitely not the Family Dog. He even wore suits occasionally. I don’t think it would have been that good a fit.”

On the other hand, the Charlatans may have been too tough a nut for any manager, even a pro like Cavallo, to crack. “They were unmanageable,” Lucy Lewis says, a sentiment echoed almost word for word by Wilhelm. “We were pretty unmanageable,” he agrees.

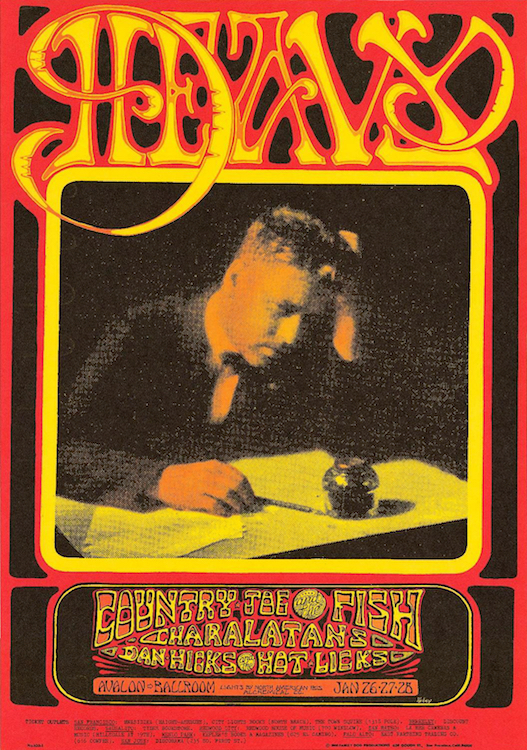

Be that as it may, if the problem with George Hunter was that he wouldn’t—or couldn’t—cede control of the band’s decision-making, the problem with Dan Hicks was that in some respects, he wanted to be the band’s George Hunter. “Dan wanted to be the frontman, all the time,” Olsen says. As it turned out, though, Hunter’s forced exit from the Charlatans coincided with Hicks’ decision to start a band of his own. Awkwardly, a few months prior to their formal split in April 1968, the Charlatans found themselves on a bill one weekend at the Avalon, playing second bill to Country Joe and the Fish, with a new group called Dan Hicks and His Hot Licks as the opener.

“I didn’t know how much he was into doing his own thing until that show,” Olsen says. “It felt like a betrayal. Dan was saying goodbye when he started the Hot Licks—that was the end of that.”

Richard Olsen of the Charlatans only learned that bandmate Dan Hicks had formed a band of his own when he saw this poster in January of 1968. That may be why Alton Kelley titled it “Heavy.” Within a few months, Hicks would leave the Charlatans for good. Via ClassicPosters.com.

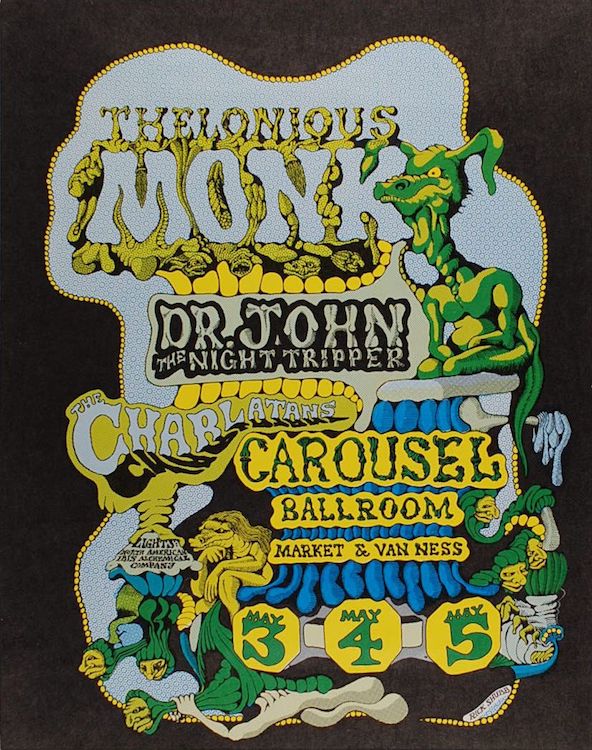

Still, the Charlatans were not quite done. In fact, one of Olsen’s favorite shows he ever played as a member of the Charlatans was in the band’s last incarnation, alongside Wilhelm on guitar, Wilson on drums, and a new keyboard player named Darrell DeVore. It occurred over the weekend of May 3, 4, and 5, 1968, when the Charlatans opened a concert at the Carousel Ballroom for psychedelic-zydeco sensation Dr. John the Night Tripper, whose highly influential “Gris-Gris” album had just come out. Jazz legend Thelonious Monk was the headliner.

“Backstage was fascinating,” Olsen remembers. “As the Charlatans, we had our look, while Dr. John and all his people from the New Orleans were doing this painted, Indian-feather thing. And then there was Thelonious Monk and all his New York guys, like the great tenor sax player Charlie Rouse, in their black suits and thin black ties. It was a trip, to say the least.”

For the next few months, Olsen and his other bandmates played a few gigs here and there, occasionally billed as the “New Charlatans,” while simultaneously working to extricate themselves from their nightmare record deal with Kama Sutra. That milestone was eventually brokered by one of the attorneys who had represented Olsen and the Charlatans after their 1967 arrest for possession of marijuana. In part, it seems, the attorney got the band out of a bad contract and into a better one so they could pay his legal bill.

One of Olsen’s favorite shows he ever played as a member of the Charlatans was in the band’s last incarnation. Within a few months, the Carousel Ballroom would become the Fillmore West. Poster by Rick Shubb, via Psychedelic Art Exchange.

“We wound up signing with Mercury-Philips, and our first album, ‘The Charlatans,’ finally came out in 1969,” Wilhelm says. “It had some pretty good tunes on it. There were a bunch of really nice songs that Darrell wrote, I had a couple of originals on there, and Richard did ‘When I Go Sailin’ By.’ Plus, we covered ‘High Coin’ by Van Dyke Parks, who came to one of our reunion shows years later at the Red Dog.”

George Hunter also contributed to the album, although not as a performer. “George designed the cover,” Wilhelm continues, “using a painting by Kent Hollister, who also painted covers for George for the ‘It’s a Beautiful Day’ album and Quicksilver’s ‘Happy Trails.’”

Unfortunately, a handsome album filled with some “pretty good tunes” was way too little, way too late, for the Charlatans. After a weekend at the Fillmore West in May of 1969, followed by a weekend at Family Dog on the Great Highway in June, the Charlatans were no more. “When you’re not invited to Monterey Pop and Woodstock, you have to know it’s over,” Olsen says.

Which didn’t mean it was necessarily over for the band’s members. Wilhelm stayed particularly busy, founding a band called Loose Gravel, which performed for seven years, before joining the Flamin’ Groovies and then going on to make a name for himself as a solo performer. Hunter would continue to do graphic design as Globe Propaganda, with side projects in furniture and cabinetry. Hicks, of course, had his Hot Licks (his posthumous memoir, “I Scare Myself,” was published earlier this year), while Olsen would go on to run Pacific High Recording in San Francisco before starting his own big-band orchestra.

Years later, in 1996, a compilation CD of material recorded between 1965 and 1968 would be released by Big Beat Records as “The Amazing Charlatans.” In 2016, selections from that album would be pressed onto burgundy vinyl, again by Big Beat. The packaging, designed by Hunter, features a Herb Greene photo of the band in its prime, shot aboard the Balclutha. But the album’s title, “The Limit of the Marvelous,” the phrase taken from that 1914 “Kar-Mi” poster, was not of Hunter’s choosing.

“I don’t know where they got off naming our album,” Hunter says. “It should have been called ‘Shipping Out’ because it was the last gasp of the group. It was made just before Dan died. But I couldn’t get any traction with anybody to call it that.” All these decades later, it’s still tough for Hunter to let go.

For his part, Wilhelm is less conflicted. “Buy two copies and play one,” he suggests.

(Thanks to Cheryl Fahrner for her invaluable help with this article.)

Read more of Ben’s work on Collectors’ Weekly. Also on Collectors Weekly: Hippie Daredevils, Psychedelic Rock Posters, and When Pianos Fell From the Sky.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.