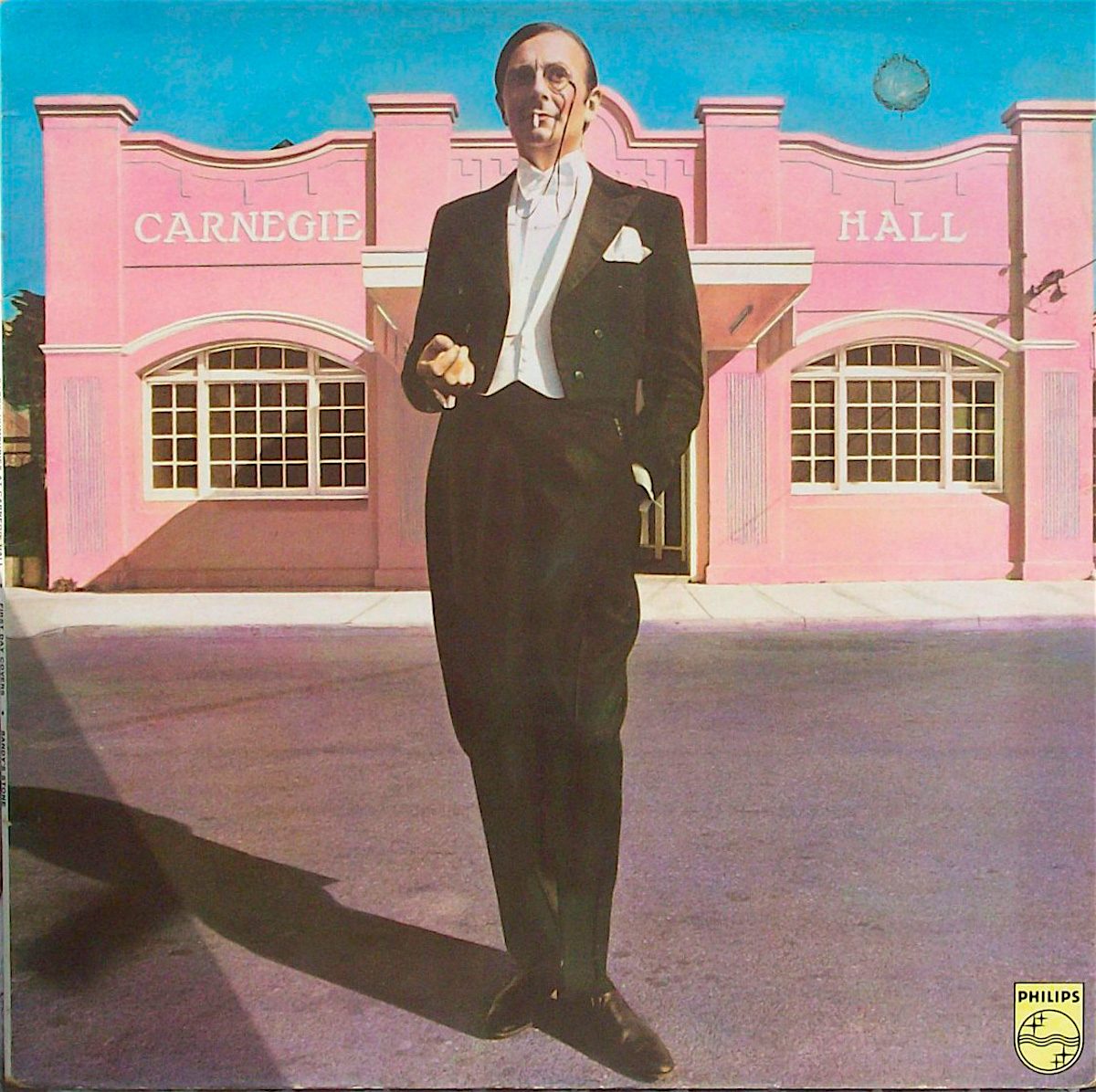

The great antipodean actor, writer, genius surrealist comic performer, father and mother of Dame Edna Everage, inventor and cousin twice removed to Sir Les Patterson, Mr. Barry Humphries has long been a fan of the artist Charles Conder. As a child, the precocious Mr. Humphries spent his hard-earned pocket money not on sweets or candy or those jazz mags on the top shelf (ahem) but on works of art like one of Conder’s lithographs, which (if only he had known) was a rather risque depiction of “a lesbian boudoir out of Balzac”. From somewhere around here, dear Mr. Humphries took a life-long interest in this relatively unknown and almost forgotten artist.

Humphries learned that Conder was an English-born/Australian-raised fin-de-siecle-cum-turn-of-the-century artist who hung out with the likes of Toulouse Lautrec, Oscar Wilde, and Augustus John. To the young suburban Humphries, Conder offered the possibility of making something great, something magical with his life.

Humphries went onto do many, many magical things with his life, for which we should all be very, very grateful, and God bless all those who sail in him. But, and it is a big butt but perfectly proportioned, this connection to Conder kept recurring at odd intervals in Humphries’ life–sometimes in the most unusual places–like it had some strange, magical significance.

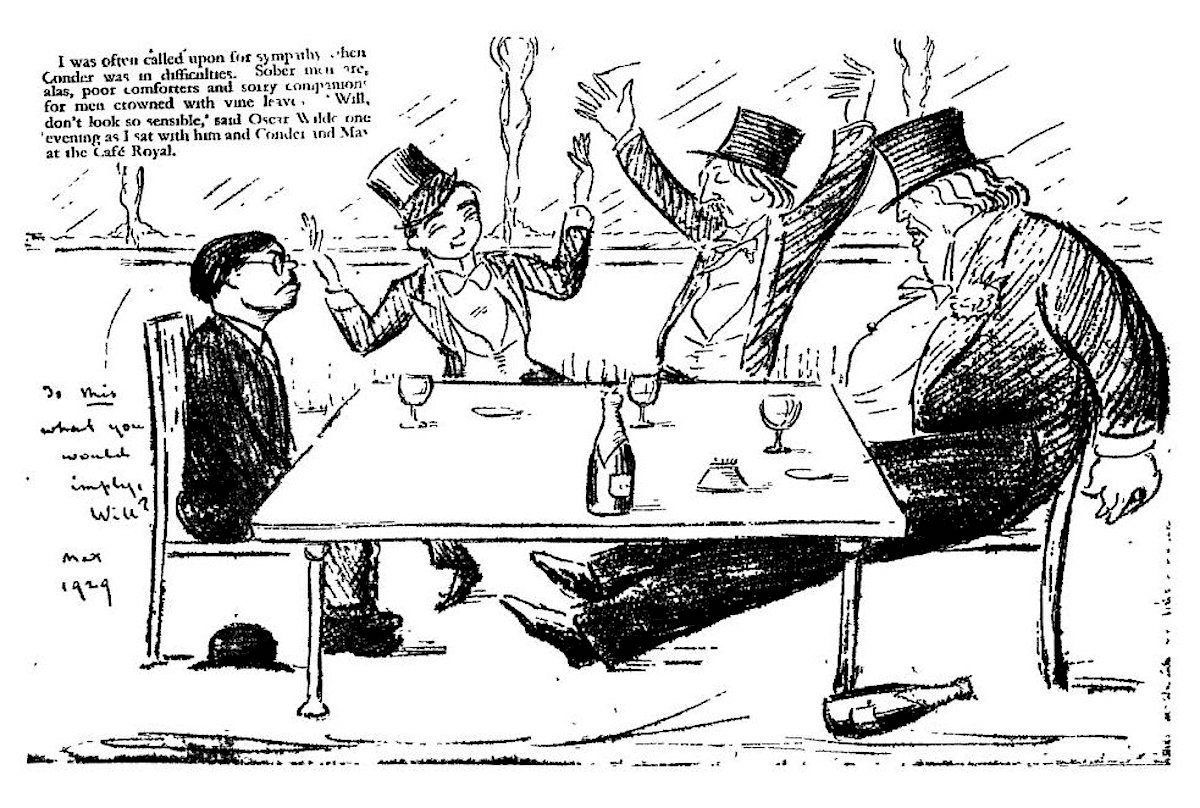

The Poet Laureate, John Betjeman was a friend of Humphries and also a fan of Conder. One day, the great poet and decrier of modernism suggested they phone up some of Conder’s old cronies to see what they could remember, if anything, about the artist. Betjeman gave Augustus John a tinkle, but the great octogenarian painter wasn’t feeling in the most reminiscent of moods, and declined the invitation to a glass of champagne in a local hostelry. Sadly, John died not long after.

On an other occasion, when Humphries who in the sixties wore his hair like a Bohemian Phil Oakey – long and combed to one side in the fashion of a Victorian fop – he was approached in a pub by a man who sounded not unlike J. Peasemold Gruntfuttock, the character played by Kenneth Williams in Round the Horne. I can imagine this character sidling up to Humphries going “Pssst. Pssst,” in his ear. This man went onto say how much Humphries looked like Conder. Cue Gruntfuttock: “You have the bearing of Conder A big man he was huge, you might say, yes, in all the right places, and right effeminate too–just like you with your long hair and your half-pint of shandy, if you catch my drift, squire….”

While browsing through a catalogue of Conder’s artwork, Humphries noticed most of the paintings were owned by a woman called Miss Amy Halford. Could she still possibly be alive? Would she be able to tell Humphries about Conder? He noted Miss Halford lived in London. Humphries flicked through the telephone directory. There was only one Miss Amy Halford listed. He picked-up the telephone and dialled the number. Ring. Ring. Ring. The click of the receiver. A woman’s tremulous voice, “Hallooooo.” Humphries explained his interest in Conder, his admiration for his work, and wondered if perchance, Miss Amy Halford recalled anything about him? Suddenly, the voice became animated, youthful, happy. “Charles, darling, you remembered me…where have you been…?” Another voice in the background. The sound of a slight struggle. The firm, sober, no-nonsense voice of a grim hired nurse came on the line: “I’m sorry, Miss Halford’s busy at the moment and can’t talk. Don’t call again.”

Or words to that effect.

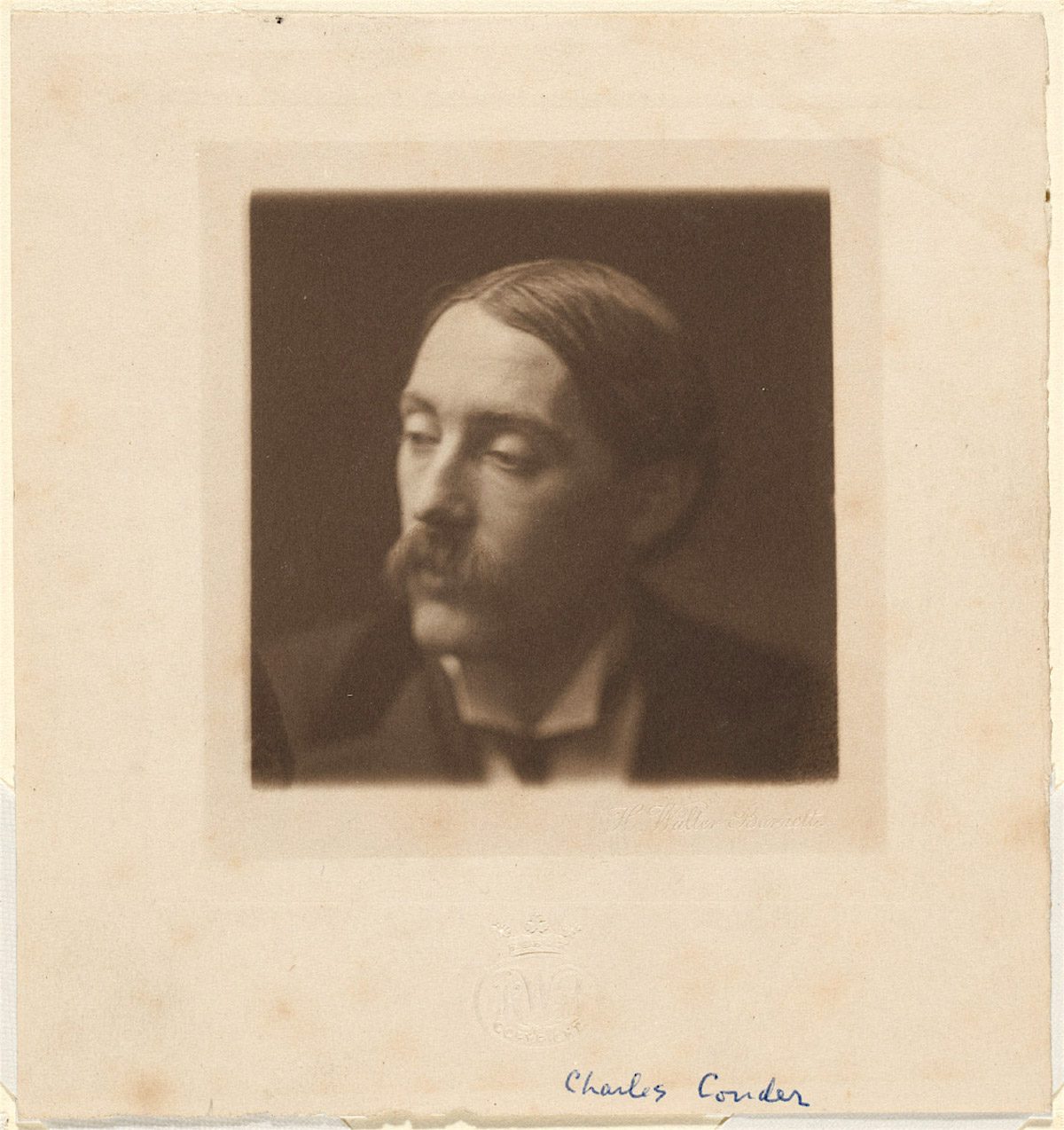

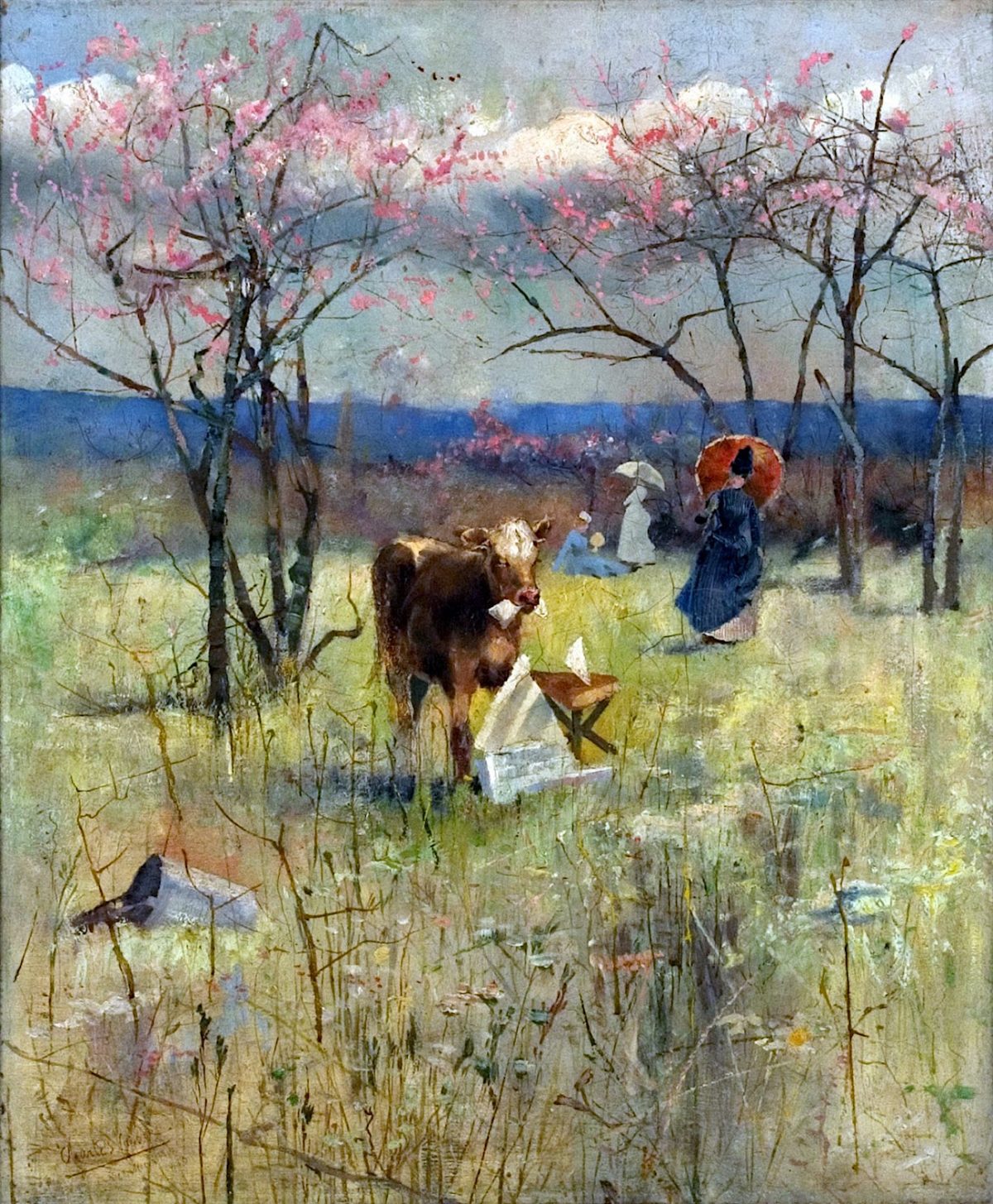

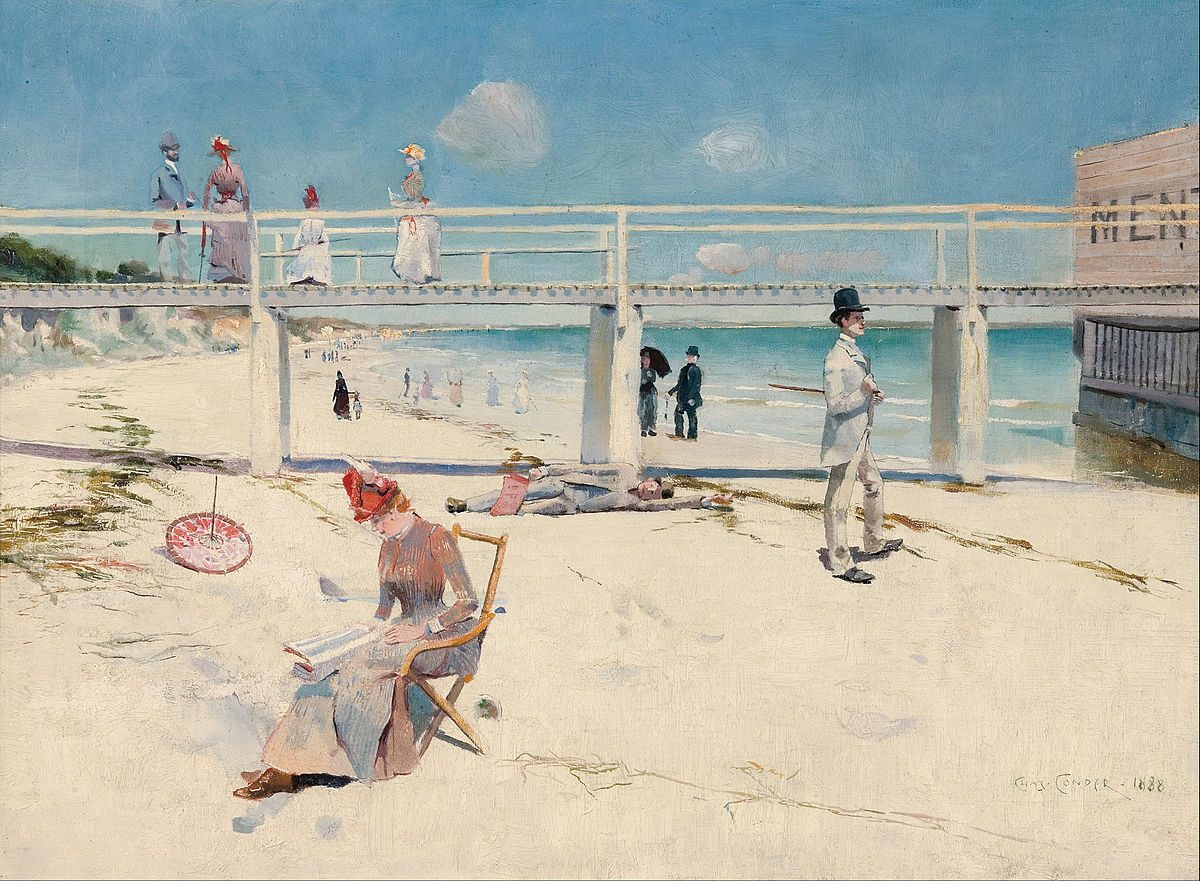

Charles Conder was born in London in 1868, the second of six children. As a child he showed considerable aptitude in art and design. At sixteen, he was sent to work with his uncle as a land surveyor in Australia. He hated the job and spent much of his time painting landscape pictures. He eventually gave up working and fell in with a bunch of other young ambitious Australian artists: Arthur Streeton, Walter Withers, Tom Roberts and Frederick McCubbin–who were known as the Heidelberg School.

Like mosts artists they were all poor and lived hand-to-mouth. Conder paid his rent by fucking the landlady and catching a dose of the clap. In 1890, he quit Australia and moved to Paris where he fell in tow with Toulouse-Lautrec who opened a whole new level of sex and debauchery.

As Humphries noted in an essay he wrote about Conder for The Spectator:

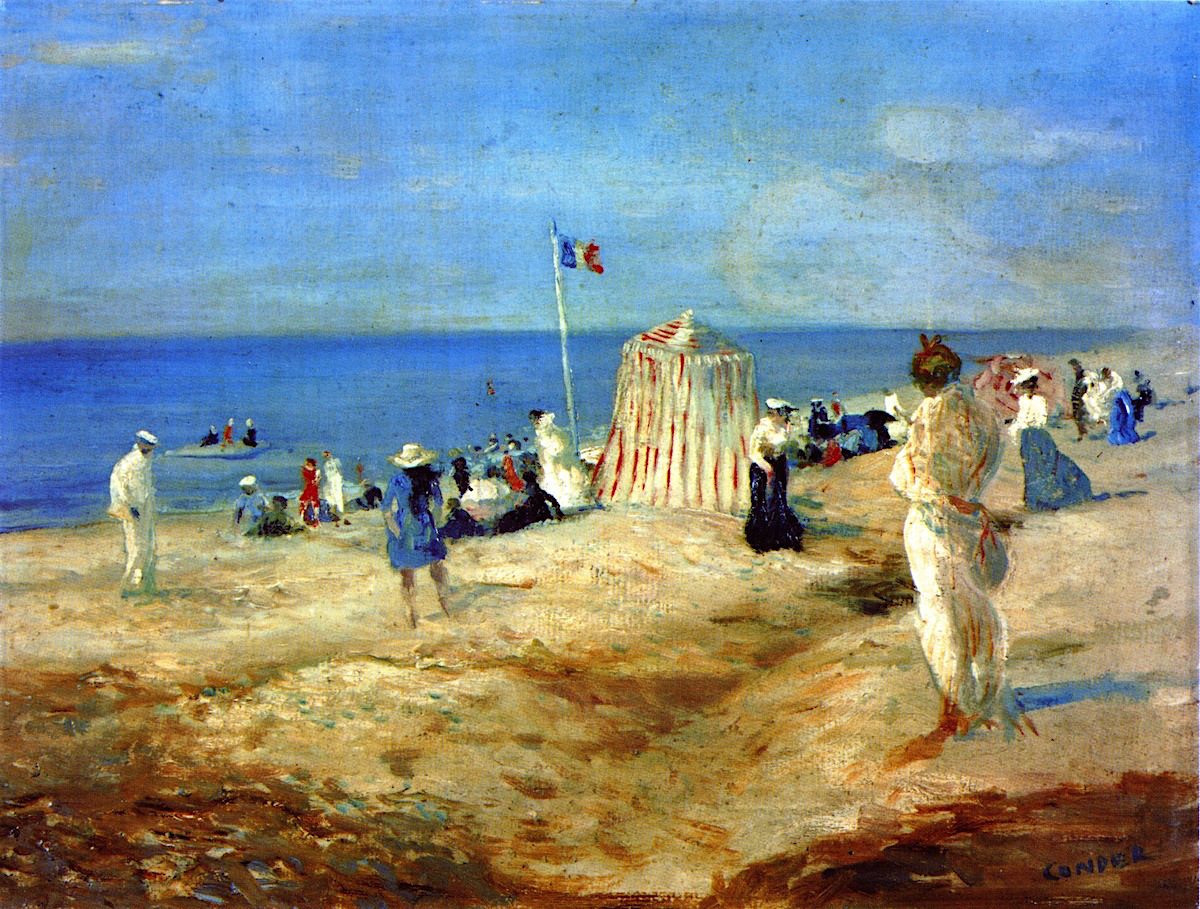

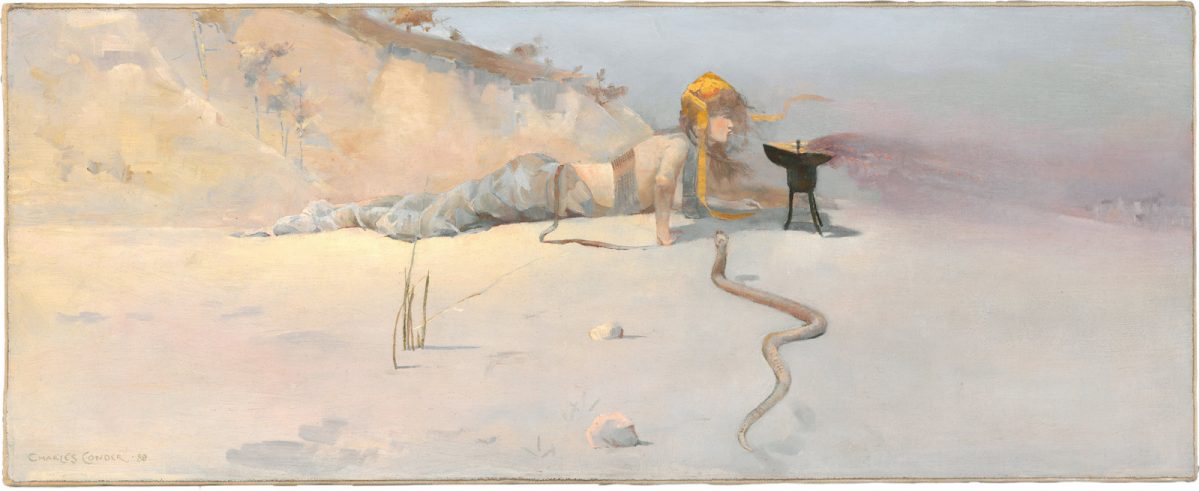

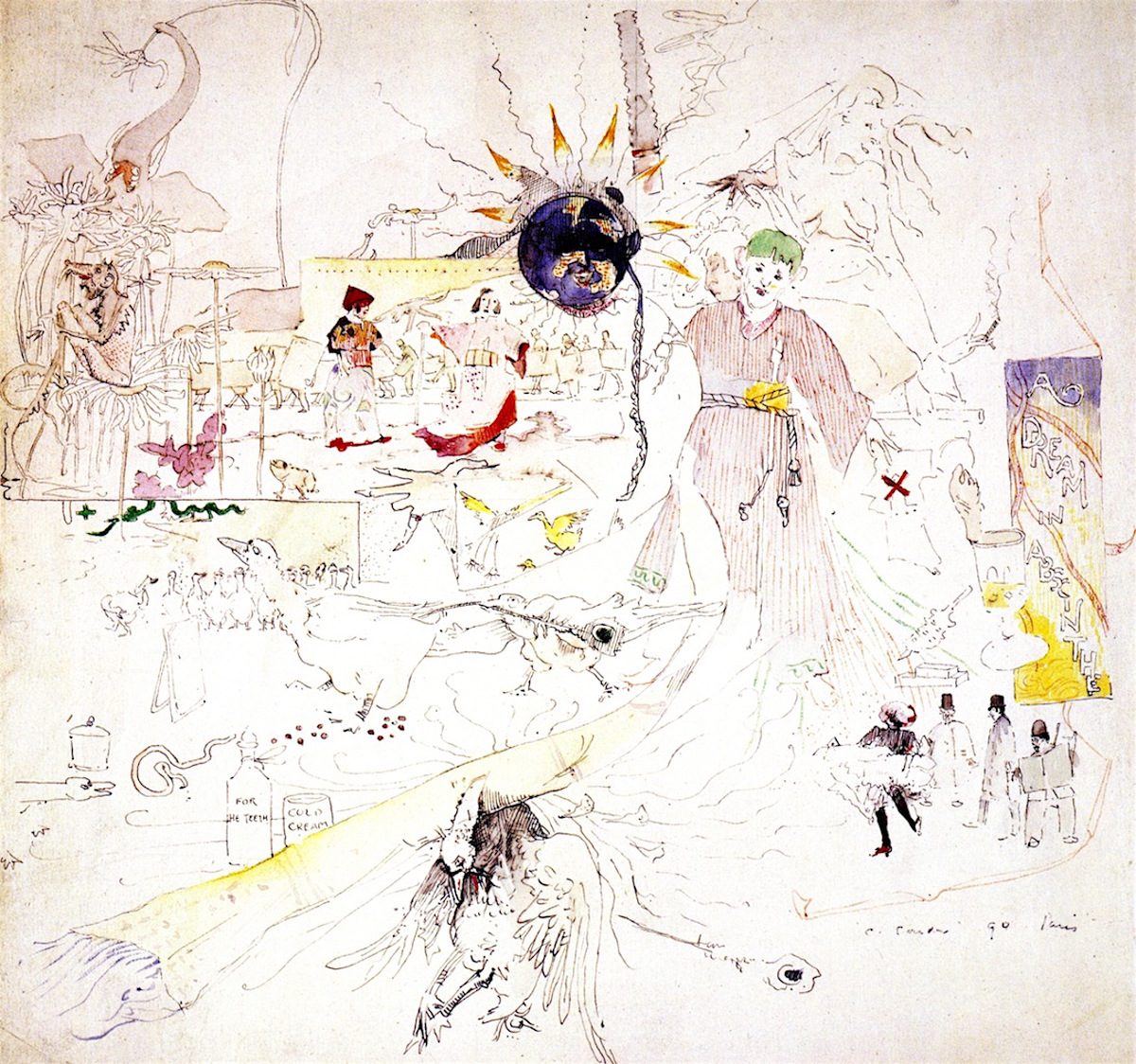

In the bohemia of Paris in the last decade of the 19th century, Conder, a boy from the bush, had discovered his artistic milieu. Conder regularly visited the open air concert at the Moulin and painted many of the artistes, including Jane Avril and La Goulue. In his memoirs Rothenstein wrote: ‘Conder saw in the Moulin and its dancers a glowing, shimmering dream of Arabian nights. Lautrec’s unpitying eyes noted only sinister figures…of degenerate and waster.’

Always a petit-maître, Conder nevertheless possessed an original and poetic vision. He was a poor draftsman but an exceptional colourist, and sometimes his style and that of Lautrec converged so that a small painting of the ‘Rat Mort’ (one of Montmartre’s older cafés and a lesbian hangout) from 1892 was so stylistically similar to the art of Lautrec it was twice catalogued as work by the French master.

Lautrec led the already susceptible Conder along dark and mysterious paths, and together they attended executions by guillotine and surgical operations, which it seems, in the Paris of that epoch, permitted a select audience of voyeurs. In the words of Rothenstein’s son John, Lautrec ‘opened up new vistas of depravity’ for Conder…

Toulouse-Lautrec painted Conder on four separate occasions, most notably in the painting The Box with the Gilded Mask (1894) where Conder looks like an immovable deity. Conder had the looks that made many women swoon and he always made the most of who and what was on offer.

From Paris Conder travelled to London where he met Oscar Wilde, Augustus John, the poet Edward Dowson, Aubrey Beardsley, and all the other fashionable types who performed daily at the Cafe Royal over Pernod and cigarettes. John appreciated Conder’s talent and for a time the two became friends–drinking together, travelling together, and painting together at Swanage.

In his memoir Chiaroscuro, John wrote:

Conder was not the robust and formidable figure of a man Will Rotherstein had led me to expect. Having once had occasion to knock him down, Will, physically small, may have unconsciously exaggerated the exploit.

Conder certainly belonged to the ‘nineties’, but his ‘naughtiness’ was all his own and part of the pure romantic nature, which had ripened so fruitily in the hot-houses of Montmartre,

Conder painted some very good seascapes at Swanage. The sea air is known to be an excitant, and Conder felt his stay would be incomplete without a romance. A charming and gifted Slade student, who happened to be a fellow-border, provided the motif, and it was not long before an engagement was announced. When Conder interviewed the young lady’s mother to make a formal request for her hand, he was met with the objection of a certain disparity of age between the parties, ‘In any case,’ he was told, ‘there’s no need to hurry: Jacob waited seven years for Rachel.’ ‘Yes,’ replied Conder, ‘but you must remember that he lived to be three hundred and seventy-six.’

John also noted that Conder’s:

…’naughtiness’ was all his own and part of the pure romantic nature, which had ripened so fruitily in the hot-houses of Motnmartre.

John admired Conder’s skill as a painter and his ability to work fast. He also liked the artist’s zest for life. But it soon became obvious that Conder was suffering from the syphilis he had contracted in Australia. His health was destroyed and he died far too young and never quite achieving the greatness his talent promised in 1909 at the Holloway Sanatorium of “general paresis of the insane.”

Ronnie Barker and Richard Beckinsale used to have a small routine they performed when filming Porridge. At the end of a day’s shoot, Beckinsale would say, “We’re coming up to the codicil.”

“What’s the codicil?” asked Barker.

“The end bit.”

“How do you spell it?”

“E, N, D, B, I, T.”

Our codicil rests with the lovely Mr Humphries, who owns the largest private collection of Conder’s work in the world. Humphries finished his essay on Conder with this little revelation:

In my years as a Conder collector I had often speculated that there might still exist a record of Conder’s last years at Virginia Water, but I dismissed the idea as impossible and that records of his death had disappeared as irrevocably as had his grave, at the little churchyard in Virginia Water. In 1948, the Royal Holloway Hospital was transferred to the NHS and for the next 12 years it became derelict, pillaged and vandalised.

A couple of years ago, to my amazement, I received a letter from a Spanish antique dealer offering me Conder’s medical records. These had survived in a heavy calf-bound volume, badly scuffed. The book had turned up at a street market in a suburb of Barcelona and had serendipitously being washed up, like precious flotsam, at my feet! It is a tragic record of the decline and death of Lautrec’s friend and subject, and one of the most exquisite talents of his day. There is an entry shortly before the end which reads:

‘Patient is well occupied; his pictures still show considerable merit.’

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.