TITANIC survivors Charlotte ‘Lottie’ Collyer and daughter Marjorie It was on a Wednesday we took the train to Southampton. Some of our friends were at the station to see us go, and some of them saw us off on the boat, I didn’t think there was any boat in the world as big as the Titanic. (named Marjery in one report), 8, had a story to tell of that terrible night. Marjorie’s account of the night was reported in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle. She and her mother became famous.

Marjorie’s tale formed part of Charlotte’s story. She had spoken to the San Francisco Call.

I don’t remember very much about the first few days of the voyage. I was a bit seasick, and kept to my cabin mod of the time. But on Sunday, April 14, I was up and about. At dinnertime, I was at my place in the saloon, and enjoyed the meal, though I thought it too heavy and rich. No effort had been spared to serve even to the second cabin passengers on that Sunday the best dinner that money could buy. After I had eaten, I listened to the orchestra for awhile; then, at perhaps nine o’clock, or half-past nine, I went to my cabin. I had just climbed into my berth when a stewardess came in. She was a sweet woman, who had been very kind to me. I take this opportunity to thank her; for I shall never see her again. She went down with the Titanic. “Do you know where we are?” she said pleasantly. “We are in what is called The Devil’s Hole.” “What does that mean?” I asked. “That it is a dangerous pert of the ocean,” she answered. “Many accidents have happened near here. They say that icebergs drift down as far as this. It’s getting to be very cold on deck, so perhaps there’s ice around us now!” She left the cabin, and I soon dropped off to sleep. Her talk about icebergs had not frightened me; but it shows that the crew were awake to the danger. As far as I can tell, we had not slackened our speed in the least. It must have been a little after ten o’clock when my husband came in and woke me up. He sat about and talked to me, for how long I do not know, before he began to make ready to go to bed. And then, the crash!

Mr. and Mrs. Harvey Collyer, had left Leatherhead, Surrey, to make a new life in the USA. Mr. Collyer planned to farm fruit in Idaho. He never made it to safety. Before the tragedy, he wrote a letter from onboard the doomed ship:

Titanic April 11th

My dear Mum and Dad

It don’t seem possible we are out on the briny wtiting to you. Well dears so far we are having a delightful trip the weather is beautiful and the ship magnificent. We can’t describe the tables it’s like a floating town. I can tell you we do swank we shall miss it on the trains as we go third on them. You would not imagine you were on a ship. There is hardly any motion she is so large we have not felt sick yet we expect to get to Queenstown today so thought I would drop this with the mails. We had a fine send off from Southampton and Mrs S and the boys with others saw us off. We will post again at new York then when we get to Payette.Lots of love don’t worry about us. Ever your loving children

Harvey, Lot & Madge

Margery tells her story:

“It was on a Wednesday we took the train to Southampton. Some of our friends were at the station to see us go, and some of them saw us off on the boat, I didn’t think there was any boat in the world as big as the Titanic. The night the Titanic hit the iceberg I was asleep. It was about 11 o’clock. I didn’t feel the bump and the ship started to back like a train, and I heard my mother say to my father that she guessed the works had stopped. He dressed himself and went on deck. ”

” I could hear feet on the decks. The boat seemed to have stopped. Then mother dressed me, took me by the hand and led me upstairs. She was in her night-dress, and I didn’t have all my clothes on. I had a big dollie that I got two Christmases before, and we were in such a hurry that I left it behind. I cried for my dollie, but we couldn’t go back.

“When we got on deck father was there going along the decks and trying to see the iceberg. But it had floated away. he said that some men had been playing cards when the ship hit the ice, and that all their cards fell on the floor, but they picked them up and went right on with the game.

“The decks were full of people. Some of them were crying. An officer said we should all put on life preservers, and my mother put one on me, and then fastened one around herself. Papa put one on too.

“I was crying for my doll, but nobody could go back and get her. Then someone said we should get into a boat and two men lifted me up and put me in a boat. My father raised me in his arms and kissed me, and then he kissed my mother. She followed me into the boat.

“The women in one of the other boats said they wanted somebody to row for them and father got in that boat.

“The stars were shining, and it was just like day. Some sailor put a rug around my mother to keep her warm. There were so many in our boat that we had to sit up all the time. Nobody could lie down. my mother was so close to one of the sailors with the oars that sometimes the oar caught in her hair and took big pieces out of it.

“There was one officer in our boat who had a pistol. Some men jumped into our boat on top of the women and crushed them and the officer said that if they didn’t stop he would shoot. Another man jumped and he shot him. My mother says I called out: ‘Don’t shoot!’ but I don’t remember it.

“The sailors had to row fast to get away from the ship. We could hear the band playing, but we didn’t see the musicians. Only, when we left, all the people on the decks were kneeling down praying, while the band played, ‘Nearer My God To Thee’.

“When the band finished one of the musicians, jumped into a boat with his instrument, and I guess he got away. While we were rowing away we heard a lot of people crying, and the women in our boat asked the officer what the noise was. He said the people on the decks were singing.

“I saw the Titanic go up in the air before she sank, and she looked ever so big.

“When we got a little way off another boat came near us, and an officer in our boat said he guessed he would go back to the wreck in it. I don’t know who he was, but he put some of the people from the other boat in ours, and got in that. Then he went back with some sailors and pulled six men into the boat.

“We rowed around for seven hours. All the time I was frightened a whole lot, and sometimes I cried. I cried hardest when I thought of my dollie back there in the water with nobody to mind it and keep it from getting wet.

“The women in the boat just sat up and didn’t say anything. We were all very tired and cold, when we saw a big light. Somebody said it was a boat, but I thought it was just a star. But it kept getting bigger and bigger, and then we saw that it was a boat. Then all the sailors rowed hard.

“We had to sleep on the floor on the new ship, and it wasn’t so nice as it was on the Titanic: but everybody was very kind to us. We thought papa would be there, but the boat he was on didn’t get to the ship.”

That ship was the Carpathia.

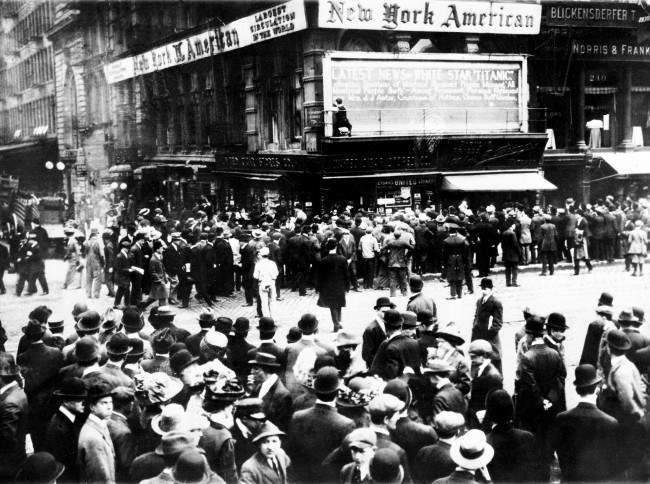

Photo: In this April 1912 file photo, crowds gather around the bulletin board of the New York American newspaper in New York, where the names of people rescued from the sinking Titanic are displayed. It was a news story that would change the news. From the moment that a brief Associated Press dispatch relayed the wireless distress call _ “Titanic … reported having struck an iceberg. The steamer said that immediate assistance was required” _ reporters and editors scrambled. In ways that seem familiar today, they adapted a dawning newsgathering technology and organized saturation coverage and managed to cover what one authority calls “the first really, truly international news event where anyone anywhere in the world could pick up a newspaper and read about it.”

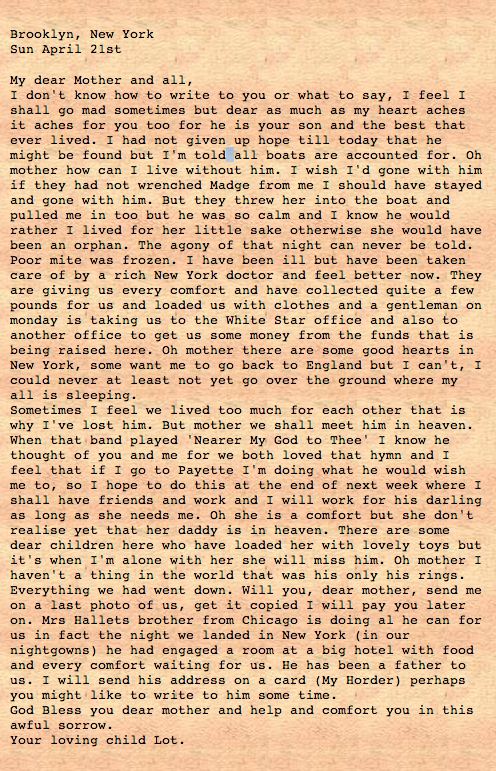

Mother and daughter arrived in New York with no money. The plan was to stay and make a go of it. Mrs Collyer wrote to her parents:

They got a little help.

From the Mansion House Titanic Relief Fund:

Collyer, Charlotte, widow and Marjorie, child.

Received total 1 3s 0d per week.

From the American Relief Fund:

The husband was drowned. His wife and seven year old daughter were saved. He was a merchant in England and had been the parish clerk in the village where they lived. They were highly respected people in fair circumstances. The wife had contracted tuberculosis and they were coming to this country to buy a fruit farm in Idaho, where they hoped the climate would be beneficial. He was carrying $5,000 in cash; this was lost, and all their household belongings. Both the widow and her daughter suffered severely from shock and exposure. They were at first unwilling to return to England, feeling that the husband would have wished them to carry out his original plan. For emergent needs she was given $200 by this Committee, and $450 by other American relief funds. After a short residence in the West she decided to return to her family in England. Through interested friends in New York City, a fund of $2,000 was raised, and she received $300 for a magazine article describing the disaster. She returned to England in June and her circumstances were reported to the English Committee, which granted £50 outright and a pension of 23 shillings a week. ($200).

People were kind:

A well-known firm of lawyers sent a check for twenty-five dollars and an offer to conduct, without charge, a suit in her behalf against the steamship company. Not a few checks came in black-bordered envelopes, with a few lines to indicate they were sent in loving memory of dear ones who had passed away. One woman writes: “My son and his little four-year old bear were saved from the wreck of the Santa Rosa less than a year ago. In thankful appreciation of that, I am glad to send the enclosed check.” One letter says: “I am only a little baby ten months old, but I am sure that, if I could understand, I should feel a very great sympathy for Mrs Collyer and her little girl.” Eleven little girls, from three to eleven years old, held a fair, and sent the proceeds to Marjorie in a dear little letter, signed by all of them, with a separate loving message from each one. Hardly a check came without some sympathizing or appreciative or cheering message. “May God’s blessing go with it”; “It was my birthday, and I was made so happy by my husband and family that I felt I might share it with this less fortunate woman”; “Her story touched a tender chord”; “I want something to make your burden lighter”; “Cheerfully offered, and I trust will be as cheerfully accepted”; “To help my plucky and unfortunate fellow country woman”; “To help brighten the future for you and little Marjorie” — these are but samples picked at random from the hundreds of letters. The fund that Mrs Collyer has so unexpectedly to herself received will enable her to start a small business and to establish a home. We are sure that the best wishes of all her American friends go with her to England.

But it was too hard in Idaho:

It did not take long, however, for Mrs Collyer to find that not all the help she could expect would suffice to make her task one that she would be able to accomplish. There was only the bare ground to start with. The forest growth, indeed, had been cut down, and the roots removed; but that was all. There was no house to live in. There confronted her, then, the problems of housing, of preparing the soil, of buying cuttings and trees from the nurseries, of setting them out, of caring for them, and of support for herself and her child until the trees came into bearing. It must be remembered that it was his wife’s failing health that was the principal consideration that led Mr Collyer to seek a home in America. He hoped that, in a wholesome, outdoor life in a more congenial climate, she might regain her strength. He had, of course, never contemplated her taking up the active pioneer work of making a fruit farm from the very beginning. He would not have dreamed her equal to it. Mrs Collyer, however, did not lack courage. Those who have read her article do not need to be told that. Earnestly she set to work to seek a possible solution to each problem she had to face. Some of them did not appear to be insuperable; but there were others that, with her lack of money and strength, daunted even her. And her strength, none too vigorous when she left England, had been sadly impaired, she soon found by the exposure and the suffering she had been through. For a time, the excitement of her terrible experiences had given her a nervous energy that she misread as renewed vitality; but, as the excitement wore off under the stern realities she encountered in the West, she began to realize her physical capital had been almost as much depleted as her financial capital. At last, she received unmistakable warnings that already she was overtaxing her powers. To go on would be surely fatal. Only then did she sadly relinquish her hopes and ambitions and decide to brave again the perils of an ocean voyage, and to return to her own country — there to seek among those nearest and dearest to her, rest for herself, and a home for Marjorie.

Marjorie and her mother returned to England. In 1914, her mother Charlotte died of Tuberculosis. Marjorie went to live with her uncle Walter on his farm at East Horsley, Surrey. She married Roy Dutton (on 25 December 1927). He died young. Marjory Collyer Dutton died on 26 February 1965, aged 61.

Spotter: Rob Baker

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.