In March 1962, a month after Billy Fury had dismissed them as his backing band – he felt they were ‘too jazzy’ – Georgie Fame and the Blue Flames started a three-year residency at The Flamingo Club. It was a

sweaty, smoky, scarlet-walled nightclub in the basement at 33-37 Wardour Street, opposite Chinatown’s Gerrard Street. It was famous for its weekend all-nighters when it stayed open from midnight until six in the morning. It’s not widely known but the Profumo affair, the political scandal that led to the resignation of John Profumo, the Secretary of State for War, in October 1963, and ultimately the fall of the Conservative government a year later, was all the fault of Georgie Fame. A slight exaggeration maybe but, if he hadn’t occasionally employed the musician Wilfred ‘Syco’ Gordon to play with the Blue Flames, there was a slim chance that Britain’s political history may have taken a completely different course.

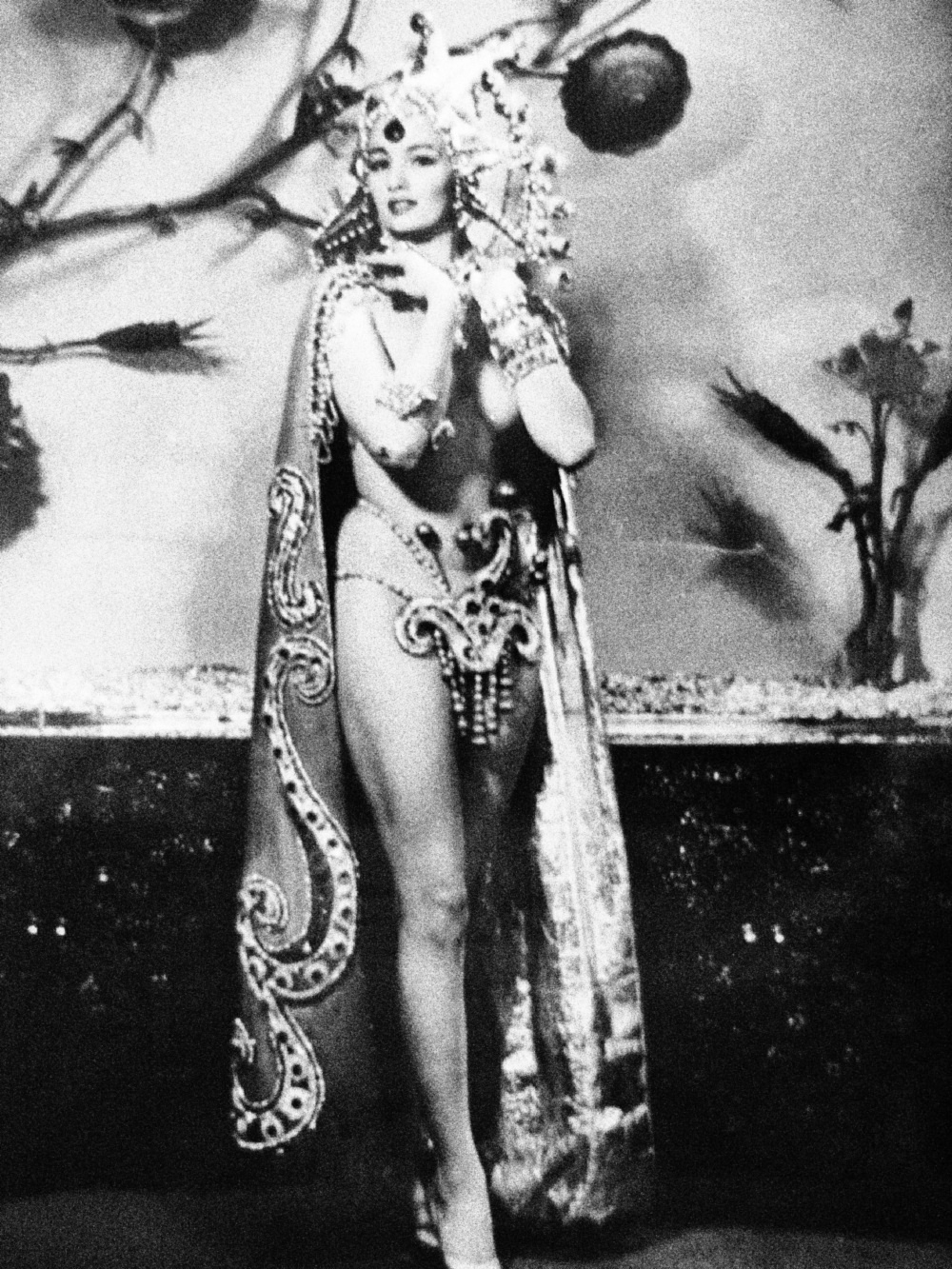

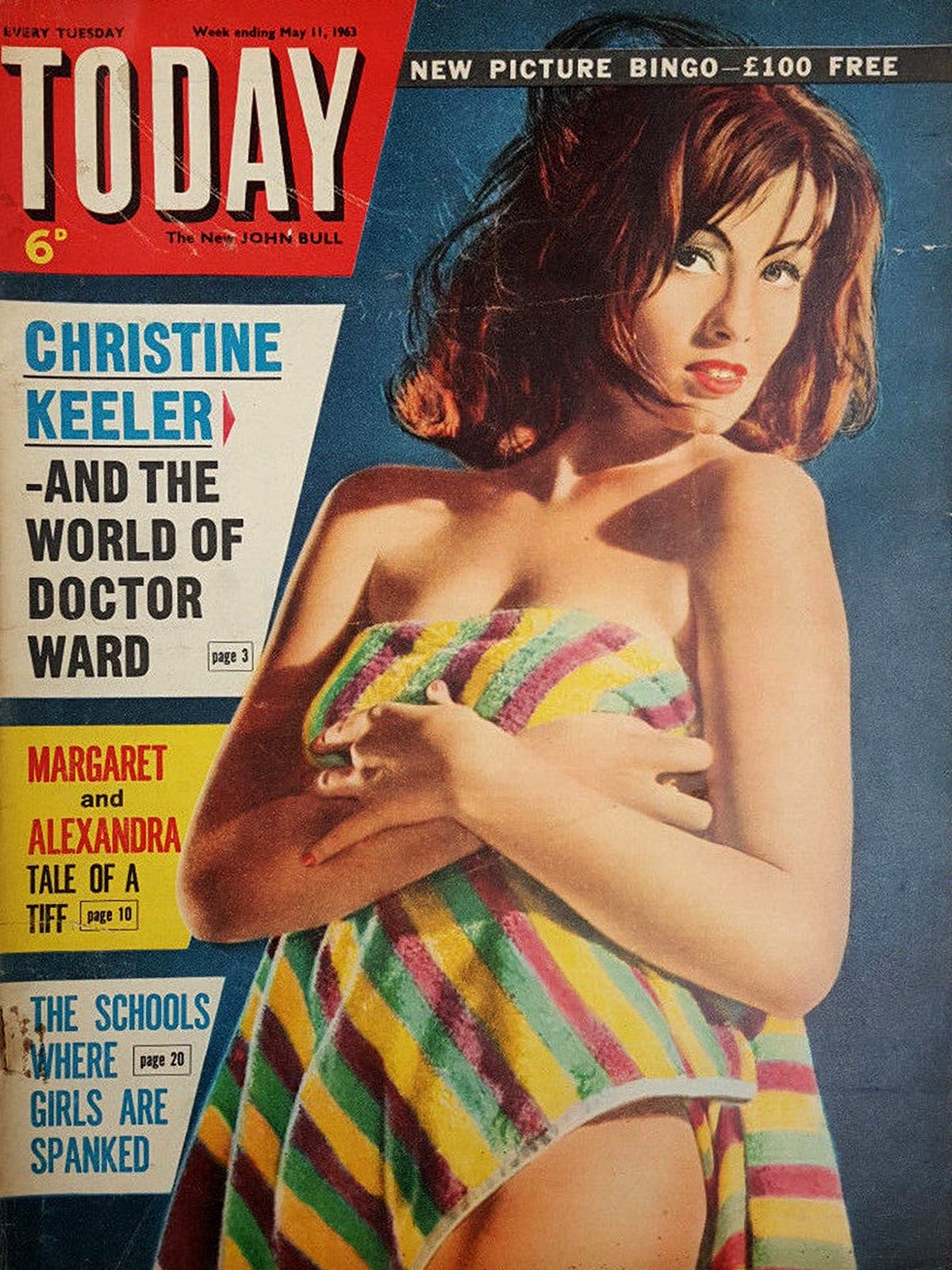

Christine Keeler was a regular visitor to the All-Nighter club at the beginning of the 1960s. She was still working most evenings at Murray’s Cabaret Club on Beak Street and had been a showgirl there since 1958 when she was just seventeen. The Cabaret, named after its owner Percy ‘Pops’ Murray, had been in Soho since 1933. In those days, to avoid being caught out by the strict licensing laws that prohibited drinking after 11 pm, the club was run on a ‘bottle party system’, where patrons signed a chit which enabled them to drink alcohol that they had previously ‘ordered’, but not paid for. By the late 1950s the club was run by Percy’s son David a personal friend of the society osteopath and portrait painter, Stephen Ward and it was at Murray’s that Ward first got to know Christine Keeler.

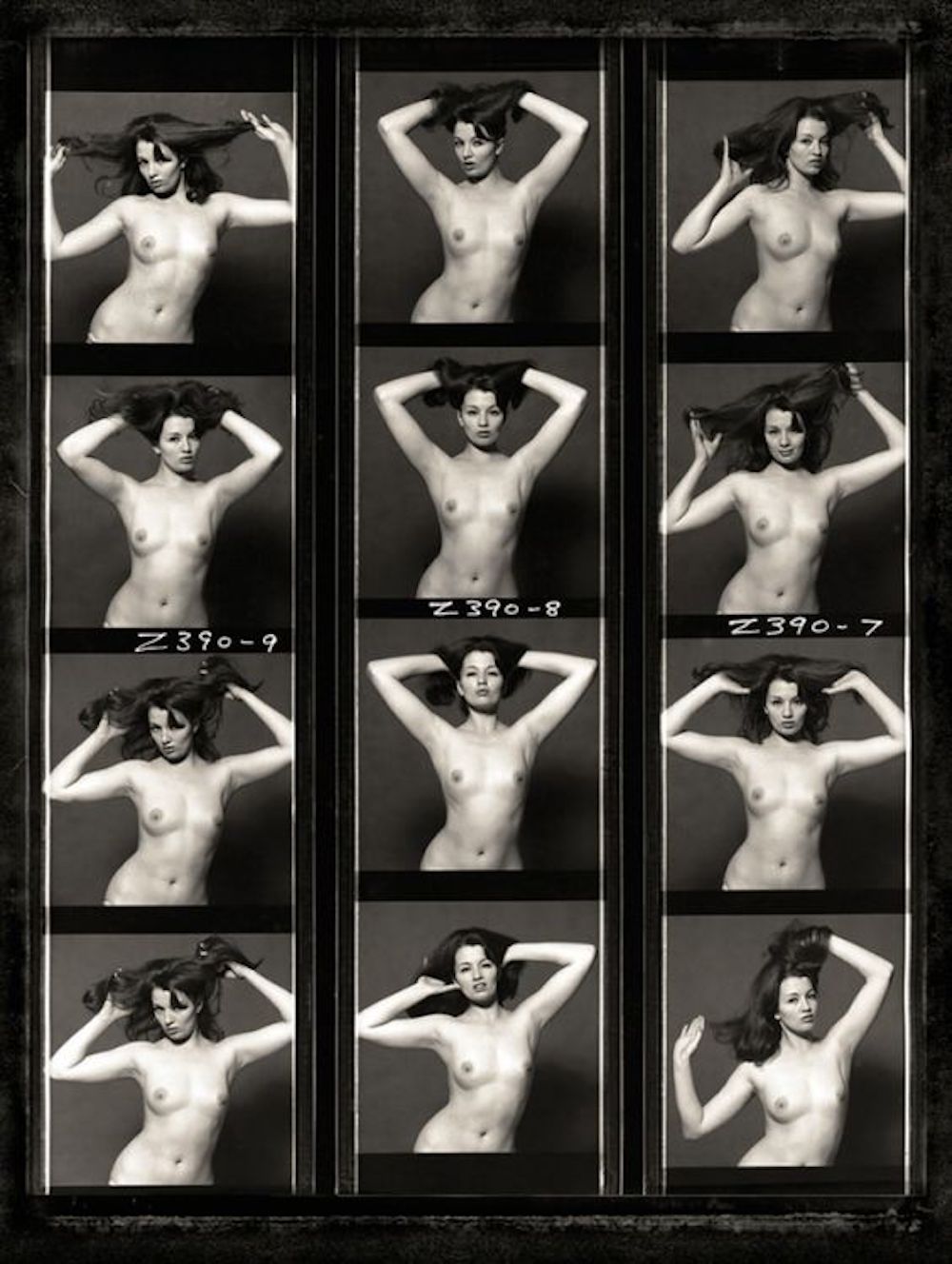

Showgirls like Keeler performed two shows a night, essentially walking around topless, wearing not much more than a pair of high heeled shoes, a tiara and sequins. They were also paid to chat to the customers between shows, encouraging them to buy expensive wine and champagne, for which they received commission and tips. Murray s was Keeler s first regular job, and her starting salary of ‘8 per week (‘175 in 2015) was substantially more than the average woman’s wage in those days. Keeler usually finished at Murray’s around 3 am, which meant that, after a dash down to the southern end of Wardour Street, she still had three hours dancing at the Flamingo. When Georgie Fame started playing regularly at the club in the spring of 1962, Keeler’s infamous affair with John Profumo had actually been over for four months. It wouldn’t be until a year later that the scandal became front page news.

Keeler and Profumo had first met on a warm summer’s evening the previous July, when Jack Profumo and his wife, Valerie Hobson, were at a dinner party held by Lord Astor at Cliveden House, an Italianate mansion and estate in Taplow a few miles from Maidenhead. Stephen Ward, who lived in one of the estate cottages, a mile or so along the Thames, asked if he and a few friends could use the swimming pool inside the walled garden that evening. When laughter and splashing were heard by the dinner guests, some wandered down to investigate. Jack Profumo, fatefully, saw a naked Christine Keeler climb out of the pool . For the next few months the Minister for War embarked on an affair with the twenty-year old showgirl. She was, however, also sleeping with the Russian spy, the assistant naval attach at the Soviet Embassy. These concurrent affairs mostly took place at Stephen Ward’s flat at Wimple Mews in Marylebone, where Christine was now living.

Captain Yevgeny Ivanov (Died January 1994) a Soviet naval attach at the Russian embassy in London in the late 1950s. He was also engaged in espionage and involved with the Profumo affair.

The Flamingo Club had actually started in 1952, after a 21-year-old film salesman and occasional 30 shillings-a-night pianist called Jeffrey Kruger had dinner at the Mapleton Hotel on Coventry Street. A big jazz fan, Kruger often wondered why every jazz club he visited was always such a dive. He would later say: ‘The biggest hold-up to jazz in this country was that it got a bad name. It was associated with dirty cellars, drink and people who had no respect for themselves. Kruger started talking to Tony Harris, the manager of the hundred-roomed hotel, and was shown a basement which he saw would be perfect for his idea of a new kind of jazz club. Jazz at the Mapleton opened in August 1952, and people came to hear modernist jazz from musicians such as Ronnie Scott, the Johnny Dankworth Seven, and Kenny Graham s Afro-Cubists. After a few months the club changed its name in honour of Kenny Graham’s composition Flamingo, and the newly named modernist Flamingo Jazz club took off. Three or four years later the Flamingo moved premises to Wardour Street, the location where it made its name.

There was, however, another club night in the basement at the Mapleton (the building is still a hotel but now called the Thistle Piccadilly). It was an all-nighter that began in 1955, and took advantage of a time when American fashion was all the rage and called itself Club Americana. For ten shillings you got live jazz and a three-course meal – tomato soup, chicken ‘n’ chips and ice cream. The night club was run by Rik and Johnny Gunnell and attracted black American servicemen who, only a decade after the end of the Second World War, were based in Britain in large numbers. The club was also frequented by members of the growing West Indian community. Club Americana, in 1958, also moved to 33 Wardour Street, and the Gunnell brothers launched the Friday and Saturday All-Nighter that operated at the same premises, and after the pre-midnight Flamingo Jazz Club had closed.

It surprised a lot of people that Jeff Kruger had got permission from the Chief Constable at the Savile Row police station to run the all-nighter. Kruger explained: ‘I told him, if you let me have an all night licence, all the kids who hang around Soho in the early hours will go there and you’ll know where they are. You can put any number of plain-clothes men inside the club, but you’ve got to promise only to arrest people outside, never inside. There’ll be no alcohol, and we ll stay open till the tube starts running so the kids can get home again.’ It wasn’t just the convenient late hours, however, that brought Christine Keeler to the Flamingo in Wardour Street. She loved the company of the black GIs and the West Indian men who were once going to Club Americana but were now coming along to the new All-Nighter club. ‘Syco’ Gordon once recalled his time at the Flamingo: ‘We’d walk in smoking ganja, taking pills and all these beautiful girls were so nice. We’d start making friends with them and start dancing. White and black would mix together. Like brother and sister. We loved dancing. We never had fights down there. All the pimps and the gangsters used to hang out down there and we had a good time. They used to have all the prostitutes you know. When they finished work they’d come down there and pick up the black guys. They just liked the black guys the way we used to dress nice they used to pay us, to go with them you know. They’d bring all their money when they finished work’.

Val Wilmer, the writer and photographer, described the Wardour Street club in the early sixties – ‘The all-nighter at The Flamingo was quite wild. The black influence was strong there and to be honest it was all a bit of a blur. They were playing things like Lord Kitcheners ‘Dr Kitch’ over the PA and Dexter Gordon and Gene Ammonds and Jack McDuff and then Ska and Bluebeat. Everybody made an effort. It was stylish hair, nice dress, pencil skirts and pale pink lipstick. That was the thing.’ Georgie Fame once recalled: ‘It was the only place where black American GIs could hang out, dance and get out of it. By midnight, when the club opened, most of them were out of it. They would have left the base late afternoon got on the train with a bottle of something and by the time they came into the club they would be raving.’ Fame remembered one face in the crowd watching him: ‘Cassius Clay, as he was then, came down when he first fought Henry Cooper. Cassius would come into town and say, “Where do the brothers hang out?” He’d be told they all go down The Flamingo.’

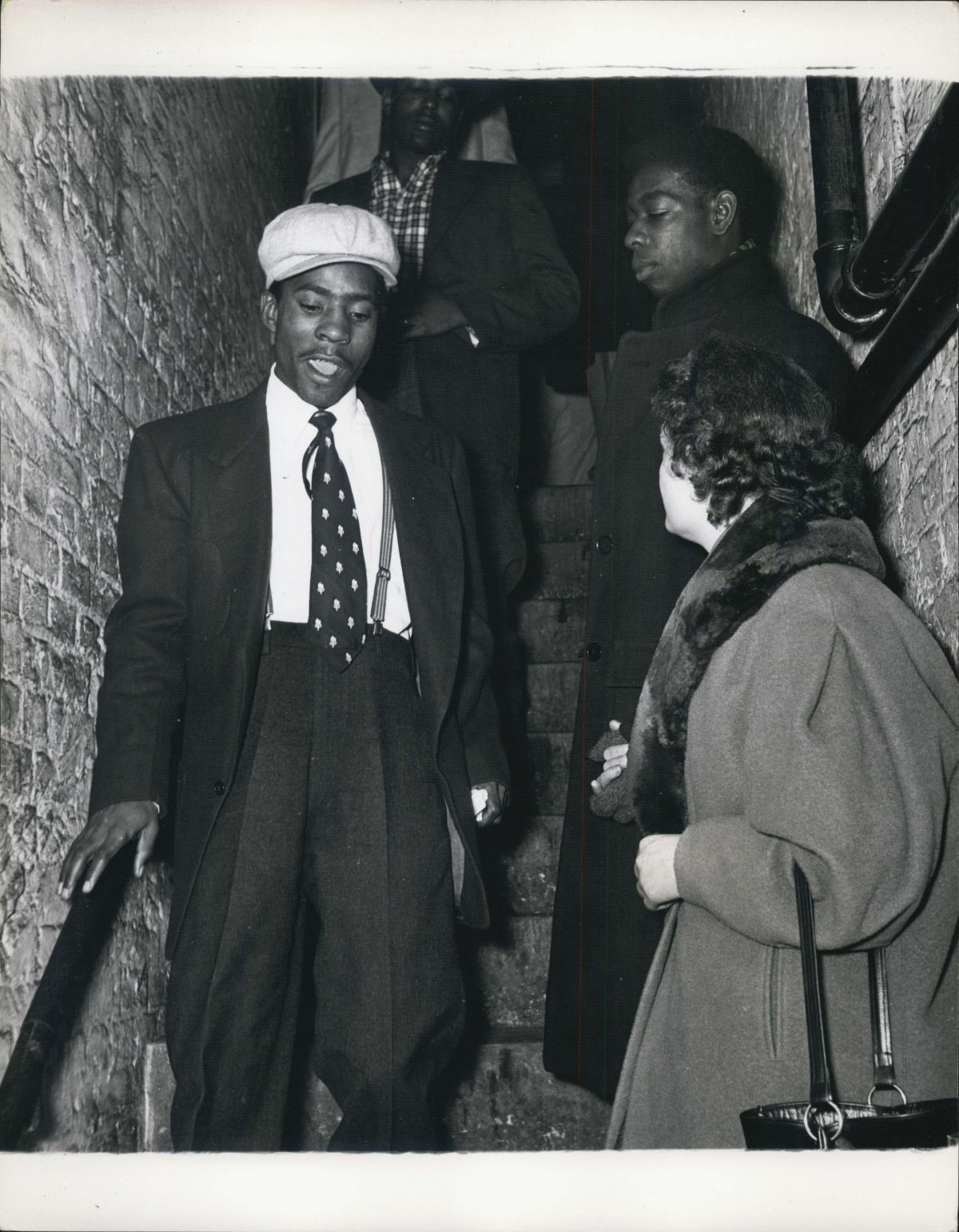

Fame, who was born Clive Powell, was instructed to change his name as part of the Larry Parnes stable (like Billy Fury and Marty Wilde amongst many others). He often employed black musicians. His trumpeter Eddie Thornton was from Jamaica, as was an occasional accompanist, Wilfred ‘Syco’ Gordon, who came to London in 1948. Syco often brought to The Flamingo Club his brother Aloysius ‘Lucky’ Gordon, a drug dealer and sometime blues singer – ‘that’s what he called himself, anyway’ Keeler once remarked. He was usually dressed in black: leather jacket, a roll-neck jumper and a beret and had a long list of convictions for fraud, assault and shop breaking. Keeler later described Lucky (the nickname came from when his parents won a lottery prize the day he was born) in her autobiography, The Truth at Last, as ‘just a thug who had been thrown out of the British army for having a go at an officer and been in trouble everywhere he went.’ Keeler first met him in the spring of 1962 when, at Stephen Ward’s behest, she bought some grass at the El Rio cafe in Notting Hill. She gave him the phone number for Stephen Ward’s flat at Wimple Mews in the hope of future drug-deals, and they became lovers, of a kind. Lucky was particularly possessive, often violently so, and after he was spurned by Keeler she later became so frightened of his continual threats that she bought a Luger to protect herself.

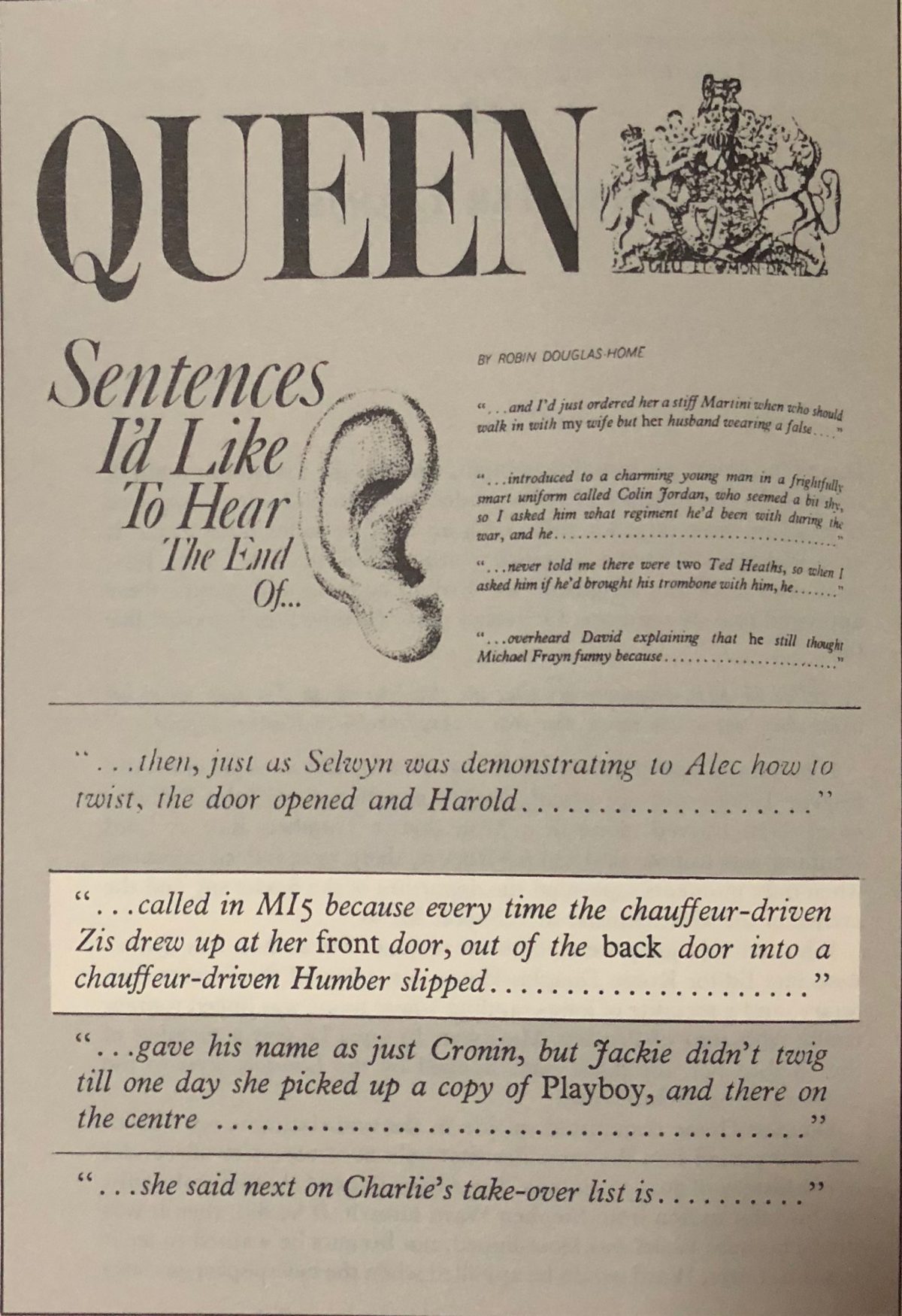

In July of that summer of 1962, a year after Christine Keeler had met John Profumo at Cliveden, the magazine Queen, owned by Jocylyn Stevens and mostly aimed at the younger side of the British Establishment, published a column called: Sentences I d like to hear the end of . It was written, as usual, by the Associate Editor of the magazine, Robin Douglas-Home. He was a nephew of Lord Home, the foreign secretary at the time (and later Prime Minster) and was also part of Princess Margaret’s social set. Home, who always kept his ears close to the ground, was exceedingly well placed to hear any society gossip. That month the column included the seemingly innocent words: ‘called in MI5 because every time the chauffeur-driven Zil drew up at her front door, out of the back door into a chauffeur-driven Humber slipped ‘. It was no more than a fragment of a sentence and utterly incomprehensible and innocuous to most people, but it sent shockwaves through Whitehall and Fleet Street. It was the first time that the security risk of Profumo, the War minister, sleeping with the same woman as a Russian Naval Attach , had got out into the open.

Meanwhile Georgie Fame and the Blue Flames were leading an exhausting, albeit exhilarating, schedule. As well as often performing at Klooks Kleek at the Railway Hotel in West Hampstead, Ricky Tick’s in Windsor, and The Scene in Ham Yard during the week, they would often play outside London on Saturday nights. Fame later remembered: ‘We’d be coming in from playing an American air force base somewhere in Suffolk and we’d throw the gear back in the wagon and drive back to London and get back to the all-nighter in time for our set. We did the 1 am and the 4.30 am set. The guys would open the way through the crowd for us and help us carry the shit on to the stage. A stabbing at the Flamingo prompted the American air force authorities to ban servicemen from the nightclub ‘

The man who held the knife in the stabbing incident to which Fame casually referred, was called Johnny Edgecombe, a 30-year-old Antiguan with several past convictions, including living off immoral earnings (for which he received six months gaol in 1959), and unlawfully possessing drugs. Christine had met him in the summer of 1962 at about the same time as the Queen magazine gossip column was published. Edgecombe, who liked to be known as the Edge , had told her that he knew Lucky and his fearsome reputation, and that he was willing to offer her protection. On the 27th October, despite the likelihood of bumping into Lucky, Keeler and Edgecombe decided to go to the All- Nighter at the Flamingo. As soon as they arrived she saw him: ‘Lucky was there as usual, smoking and drinking with his cronies. And mad- eyed ‘

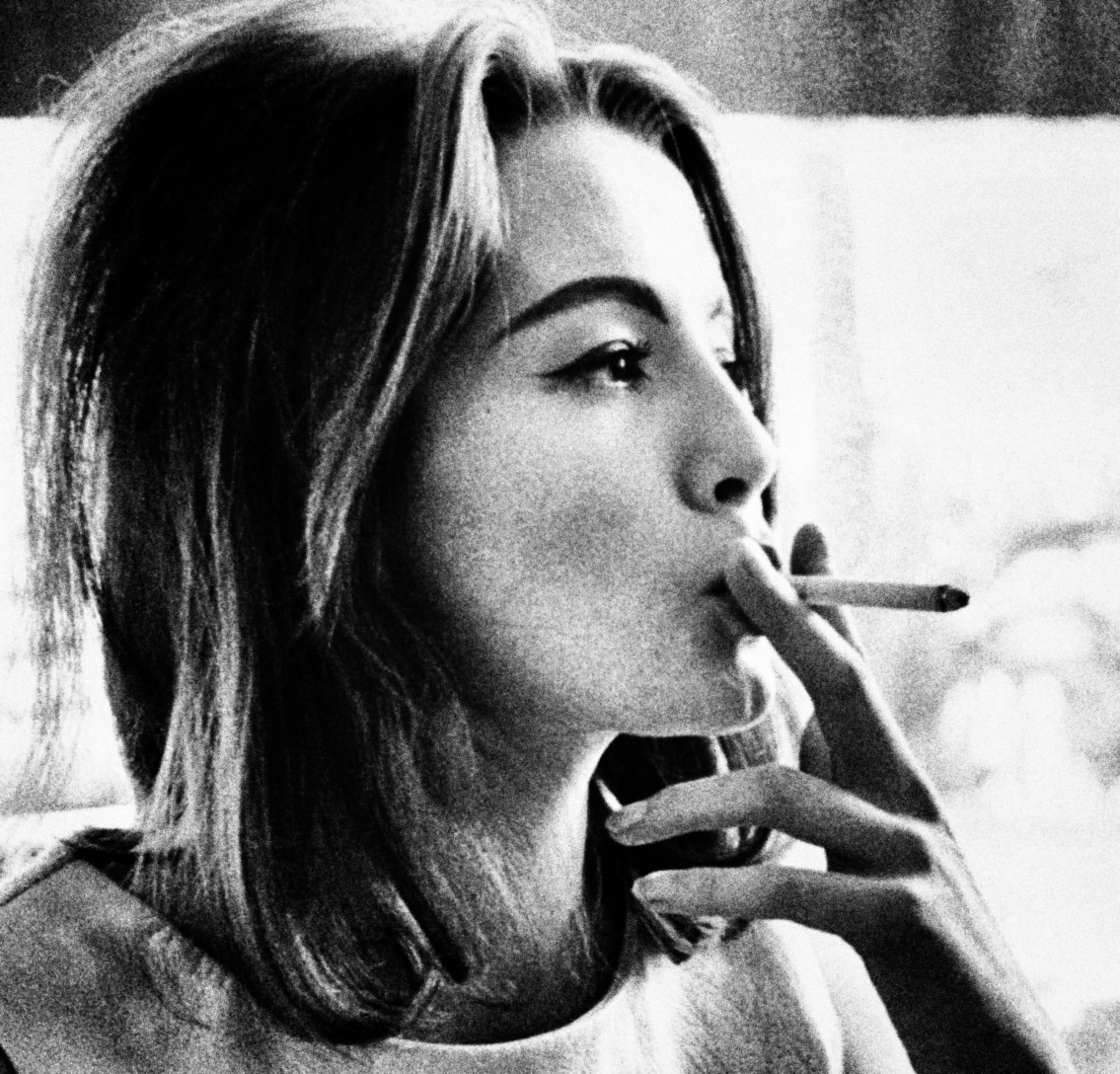

CHRISTINE KEELER – 1964 – by Hatami

Lucky rushed over and picked up a chair as a weapon and then chased Keeler and Edgecombe through the club. Keeler managed to escape and hide on the crowded dance floor but Lucky caught Johnnie and they squared up to each other. Lucky suddenly made a dash for the exit but the bouncers stopped him at the door. Edgecombe slowly walked over towards a trapped Lucky and then in an instant whipped out a flick-knife. Keeler later recalled: ‘The knife flashed and then Lucky s face was pouring with blood. Lucky had his hands to his face. He screamed with rage and pain. The cut ran from his forehead to his chin down the side of his face, and the blood poured into his eyes, blinding him. You ll go inside for this! He screamed. I ll get the law, you ll go inside. ‘ [17]

Edgecombe grabbed hold of Christine s arm and they ran out of the Flamingo as fast as they could. Later that night they dropped into a shebeen , an illicit bar, on Powis Terrace in Ladbroke Grove. They were told that they had just missed Lucky Gordon who, accompanied by police officers, was looking for them both. A few days later, after Gordon had been treated for his wound at a local hospital, he sent Christine, in a fit of jealousy, the seventeen used stitches from his face. He warned her that for each stitch he had sent she would get two on her face in return. Meanwhile, Keeler and Edgecombe were in hiding at a friend of his in Brentford. It wasn t long, however, before Keeler became tired of this arrangement and told Edgecombe she was leaving. Brentford was not the sort of place to which she had lately become accustomed.

On 14th December 1962, Keeler went to visit Mandy Rice-Davies who was now living at the Wimpole Mews flat. Edgecombe, still desperately upset that Christine had left him, called the flat’s telephone and by chance Christine answered it. Now he knew where she was he arrived in a cab within minutes. When Keeler refused to speak to him he angrily shot six bullets at the door of the flat and after she poked her head out to plead with him to go away, one up at the window. No one was hit, but the gunshots were to echo for many months around London. Frightened, Christine called Ward at his surgery and he in turn called the police who quickly arrived and arrested Edgecombe.

The incident gave the press, who were far more deferential to the Establishment at the time, the chance to explore the Profumo rumours that had been circulating around Fleet Street for months. What seemed a motiveless shooting in a quiet Marylebone side street would normally have attracted little attention; but Edgecombe’s appearance at the magistrates court the following day made the front pages. He was charged not only for the shooting at Wimpole Mews, but also for slashing Lucky’s face at the Flamingo.

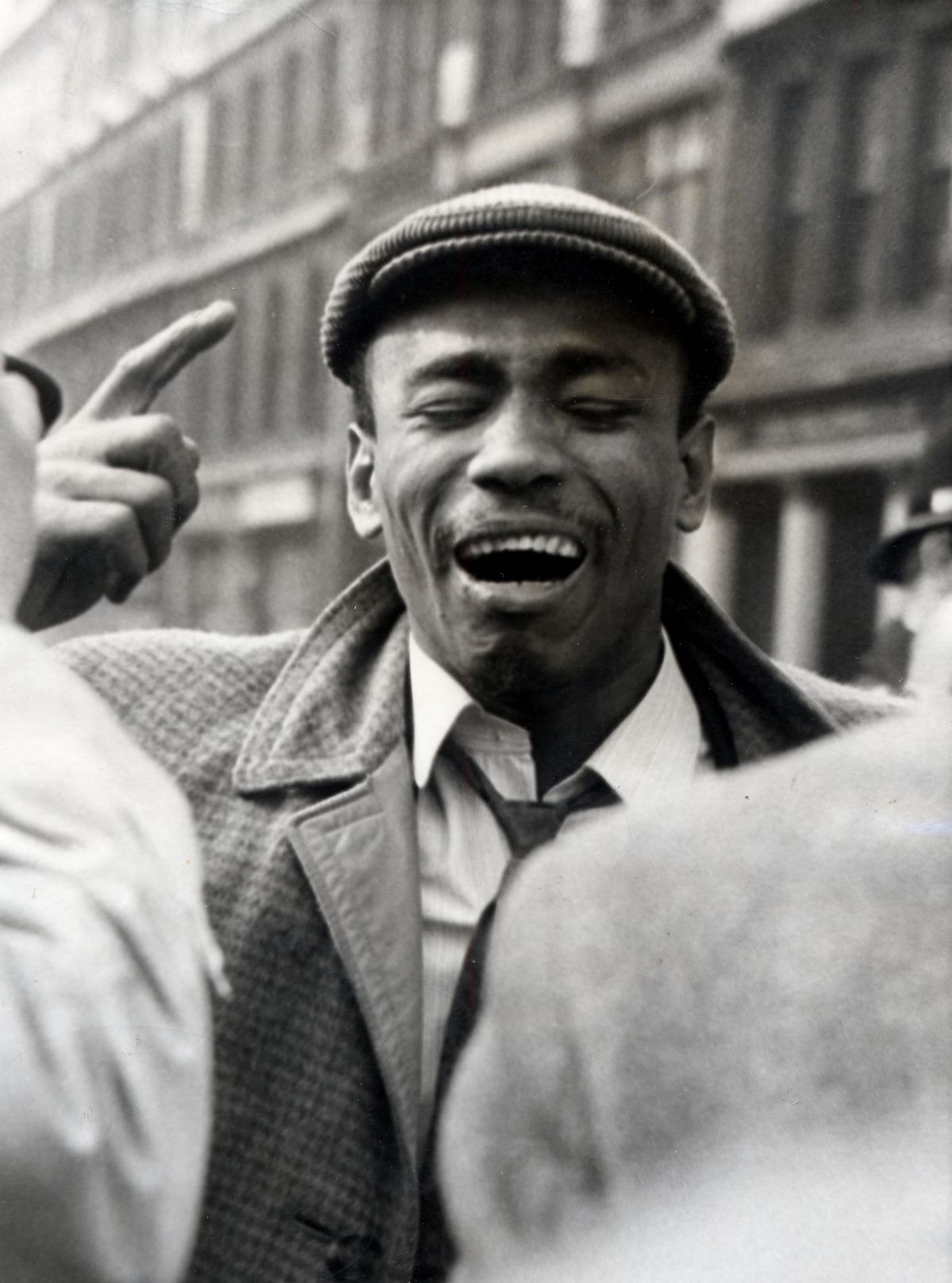

Mandatory Credit: Photo by Daily Mail / Rex Features ( 897067a )

Aloysius Gordon Known As Lucky Gordon Jamaican Singer And Former Lover Of Christine Keeler. Gordon Was Involved In The Profumo Affair In The Sixties. He Is Pictured Here Outside The Old Bailey After An Altercation With The Police.

Aloysius Gordon Known As Lucky Gordon Jamaican Singer And Former Lover Of Christine Keeler. Gordon Was Involved In The Profumo Affair In The Sixties. He Is Pictured Here Outside The Old Bailey After An Altercation With The Police.

E0WM2W Jul. 10, 1963 – ”LUCKY” Gordon and John Edgecombe on the way to see Lord Denning responsible for an enquiry into what would become to be known as the Profumo Affair.

Three months later Edgecombe, an Antiguan, but described in the newspapers as a Jamaican film-extra, was tried at the Old Bailey on 14th March 1963. He told the jury that he had first met Miss Keeler the previous June and they had lived together at three addresses. ‘I suppose I was in love with her,’ he told the court. Miss Keeler, however, was particularly conspicuous by her absence. She had been whisked off to Spain. Somebody, somewhere thought various people would be badly compromised if she were allowed to talk in the witness box. Because of Keeler’s absence, Edgecombe was found not guilty for the attempted murder of his former lover, but also, despite Gordon telling the jury of the fight at the Flamingo and showing them the five-inch scar caused by Edgecombe s knife, acquitted of wounding Lucky. Edgecombe, however, was found guilty of possession of an illegal firearm, for which he received seven years in gaol but was to serve just over five. Years later the thirty-year old Antiguan wrote that he thought his trial was racially motivated: The Englishmen didn’t mind having a black guy for a brother, but they didn t want him as a brother-in-law. The British people wouldn’t wear a situation where a government minister was sleeping with the same chick as a black guy. I was an embarrassment to the Government and they had to put me away and shut me up. If I had been a white guy. It would have blown over.

English former model, showgirl and key figure in the Profumo scandal, Christine Keeler posed wearing a swimsuit on a beach in Cannes, France in May 1963. (Photo by Popperfoto/Getty Images)

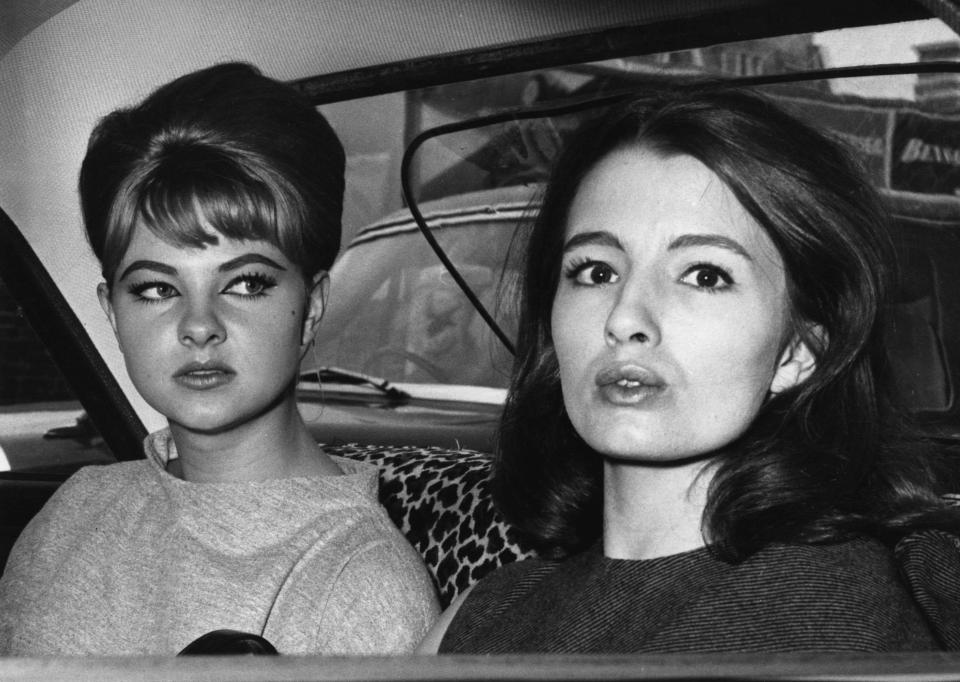

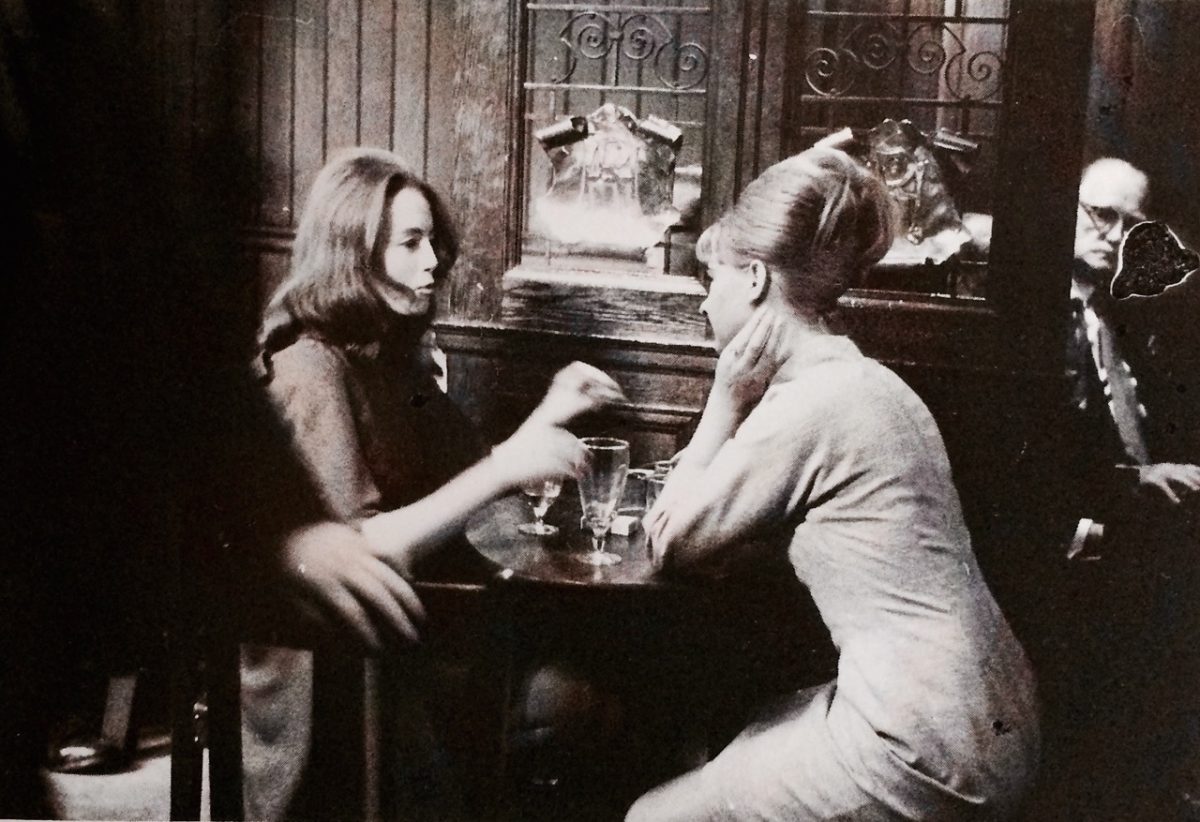

Christine Keeler, right, and Mandy Rice-Davies leaving the Old Bailey after the conclusion of the fist day’s hearing of the trial at the Old Bailey in which Dr. Stephen Ward, 50 year old osteopath faces vice charges.

PA NEWS PHOTO 22/7/63 : CHRISTINE KEELER AND MARILYN RICE-DAVIES DRIVING AWAY FROM THE OLD BAILEY, LONDON AFTER THE FIRST DAY’S HEARING IN WHICH DR. STEPHEN WARD THE 50 YEAR OLD OSTEOPATH FACES VICE CHARGES. DURING THE HEARING MR. MERVYN GRIFFITH JONES, PROSECUTING GAVE AN UNDERTAKING THAT NO ACTION WOULD BE TAKEN AGAINST HER

Christine Keeler and Mandy Rice-Davies lunch Ward Trial by Doreen Spooner

Daily Mirror Christine Keeler scoop

by Tom Blau, modern C-type print from original transparency, 1963

The next day, only encouraged by the non-appearance of Keeler, the Daily Express signalled the gathering political storm by putting the headline ‘WAR MINISTER SHOCK’ adjacent to a large photograph of Keeler under the word: ‘VANISHED’. The first real public hint of the scandal growing around Jack Profumo came a week later during a late- night Commons debate. George Wigg, with parliamentary privilege, referred to rumours surrounding 21-year-old Miss Keeler, who was then only known as the missing witness in Edgecombe’s Old Bailey shooting case, and asked the Home Secretary to deny them.

Profumo was urgently woken from his sleep during the middle of the night, and taken to a meeting with Tory party grandees to work out his next step. Later that day, Profumo made a statement to a tense and full House of Commons: ‘I have not seen her since December 1961. It is wholly and completely untrue that I am in any way connected with or responsible for her absence from the trial’. Mr Profumo then continued and uttered the fateful words: ‘There has been no impropriety whatsoever in my acquaintance with Miss Keeler.’

Profumo left the chamber to the cheers of the Conservative MPs. While the Prime Minister, Harold Macmillan, showed his support by walking along side him with his hand on the minister s shoulder. Later that evening, confident that it would all soon blow over, Profumo went for a dance at Quaglino s with his wife, the former actress, Valerie Hobson. A few days later, during a lunch with Chapman Pincher, the experienced Daily Express Defence correspondent who was also a friend, Profumo said: ‘Look, I love my wife, and she loves me, and that s all that matters.

Anyway, who s going to believe the word of this whore against the word of a man who has been in Government for ten years?’

On April 1st 1963 Christine was fined for her non-appearance at Edgecombe’s trial while, outside the court, Lucky Gordon was bundled away by the Metropolitan police, shouting ‘I love that girl!’. Two months later Gordon was given a three-year prison sentence for supposedly assaulting Keeler. By now details of the story involving Profumo and the Russian attach /spy Ivananov were emerging, drip by drip. The chain of events that started with the fight of Keeler s jealous ex-lovers at The Flamingo All-Nighter Club, eventually caused John Profumo to stand up in the House of Commons on June 6 1963 and make a statement: ‘I have come to realise that, by this deception, I have been guilty of a grave misdemeanour.’ The next day, in its leader, the Daily Mirror spoke for much of the population: ‘What the hell is going on in this country?’

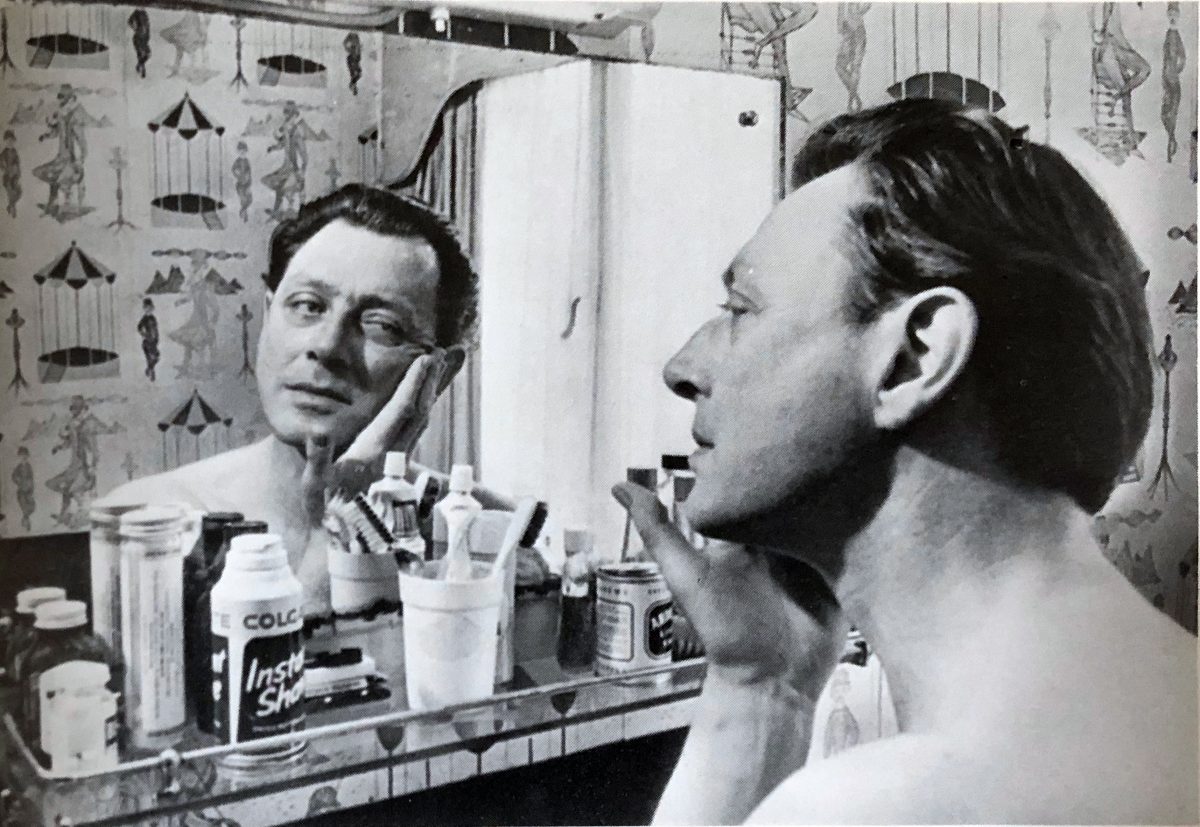

ER681F Dr Stephen Ward, pictured at his flat, Bryanston Mews West, Marylebone, London, 22nd June 1963.

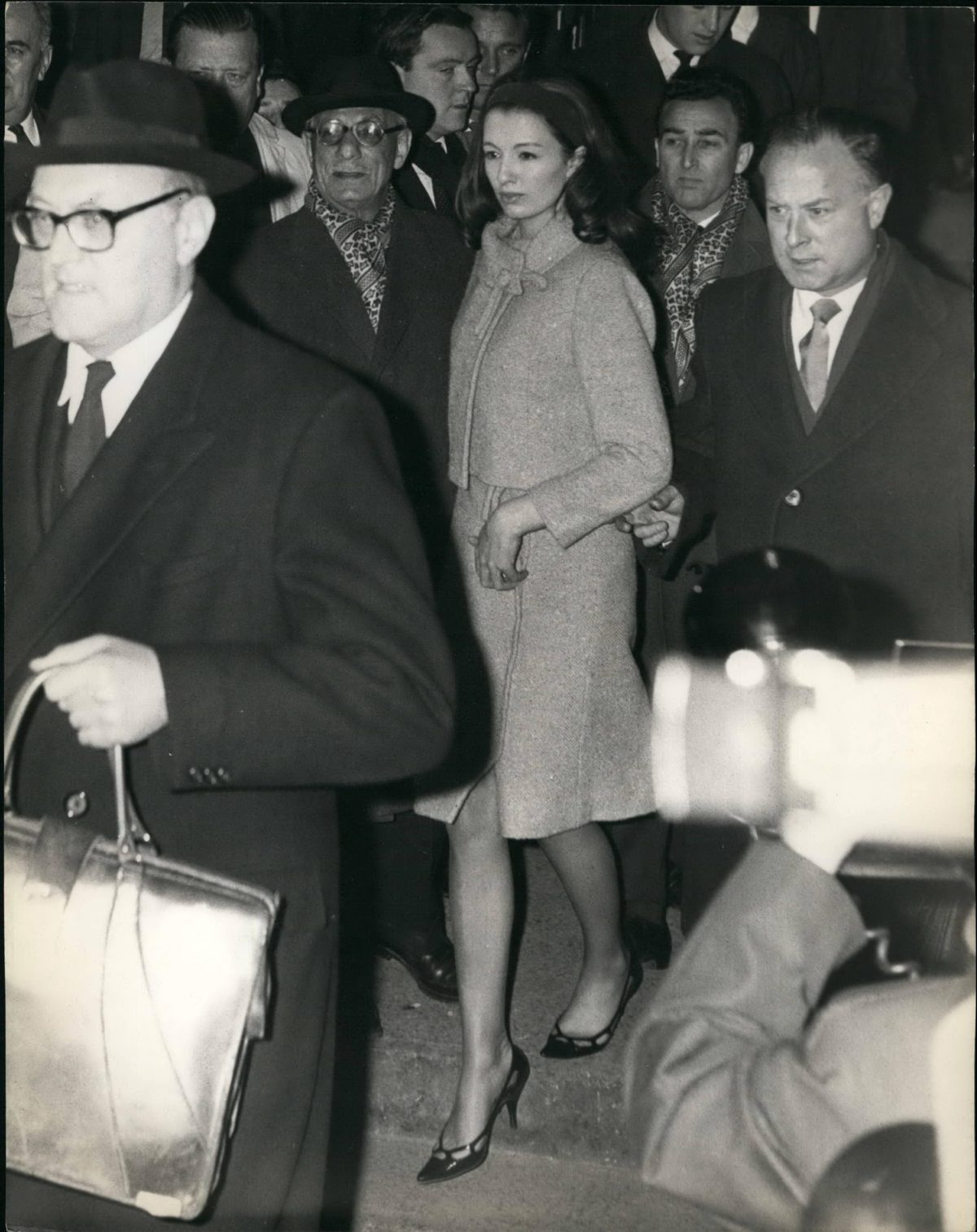

Christine Keeler, 21, arrives at Old Bailey in London, in this file photo dated April 1, 1963, where her bail was forfeited for her failure to appear earlier as a court witness in a shooting case against her ex-lover.

Two days later Stephen Ward was arrested and charged with several counts of living off immoral earnings and of procuring. By now his rich, establishment, society friends were fading away. Ward s trial at the Old Bailey began on 22nd July 1963 during which the prosecuting counsel, Melvyn Griffith-Jones, portrayed Ward as representing ‘the very depths of lechery and depravity’. According to Geoffrey Robertson QC, author of Stephen Ward Was Innocent OK, the Judge, Mr Justice Marshall, made repeated improper interventions in the trial while misdirecting the jury on both the evidence and the law most grievously in the definition of prostitution. Robertson also maintained that the judge’s summing up was cruelly biased. He was actually only half way through the summing up and was to continue the following day when, on 30 July, after writing several letters to friends, Ward took a massive overdose of Nembutal. In one of Ward s notes, to Noel Howard-Jones at whose Chelsea home he had been staying, he wrote: Dear Noel, I m sorry I had to do this here! I do hope I haven t let people down too much. I tried to do my stuff, but after Marshall’s summing up I ve given up all hope.’ Ward added, The car needs oil in the gear box, by the way, be happy in it.’

The next day Mr Justice Marshall completed his summing-up, despite the absence of Ward, and after over four hours of deliberating, the jury found Ward guilty. Stephen Ward, essentially, had been unable to prove that Mandy Rice-Davies and Christine Keeler’s rent hadn’t come from the proceedings of prostitution, and he was convicted on those two counts. The sentence was postponed until Ward was fit to appear, but on 3 August he died without ever regaining consciousness. Keeler’s solicitor read out a statement to say that she was: ‘very distressed by the news of the death of Dr Ward, who has played a central part in her life, and for whom her feelings were very strong. Under these circumstances she does not intend to carry out the plans to take part in a film based on her life, due to commence shooting next week.’

On 6 December 1963, after a drunken tape-recorded confession that she had lied about Gordon assaulting her, Keeler pleaded guilty of perjury and conspiracy to obstruct justice. Her barrister pleaded to the judge before sentencing: ‘Ward is dead, Profumo is disgraced. And now I know your lordship will resist the temptation to take what I might call society s pound of flesh.’ Lord Denning in his recent report about the Profumo affair had recently interviewed Keeler: ‘Let no one judge her too harshly. She was not yet 21. And since the age of 16 she had become enmeshed in a net of wickedness.’ It was all to no avail and the judge sentenced Christine Keeler to nine months in jail, which ended what her barrister termed: ‘the last chapter in this long saga that has been called the Keeler affair.’

Dr Stephen Ward (died August 1963) Osteophath And Artist Involved In The Christine Keeler And John Profumo Scandal In The Sixties. He Is Pictured Here Being Carried Into Hospital After Taking An Overdose In July 1963 He Died A Few Days Later.

E0WT14 Dec. 12, 1963 – Christine Keeler trail at the Old Bailey: The trial in which Christine Keeler and others are accused of conspiracy

At the end of 1963, Georgie Fame and the Blue Flames recorded a live album entitled Rhythm and Blues at ‘The Flamingo’ and it was released in early 1964. Fame was now managed by Rik Gunnell, while the publicity for the record was looked after by Andrew Loog Oldham, who was also the manager of the Rolling Stones. In October of that year, despite a change of leadership, the Conservative government was narrowly defeated by the Labour Party, and Harold Wilson became prime minister. After the much publicised trouble at The Flamingo, American service men were banned from visiting the club. Drawn by the weekend all-nighters and the music policy of black American R ‘n’ B, Soul, and jazz, The Flamingo Club was already the favourite hang-out for London s newest teenager cult, the Mods. But that’s a different story.

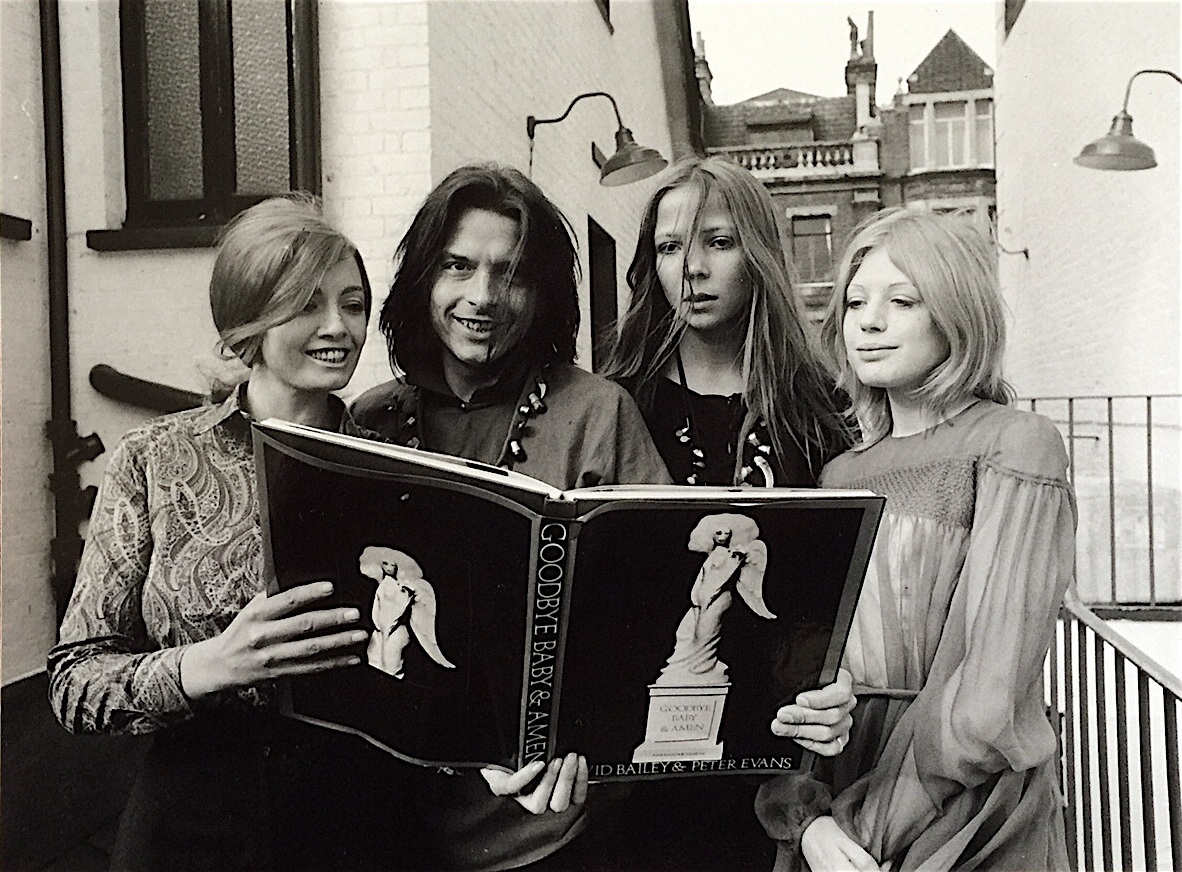

Christine Keeler (left), whose name figured prominently a few years back in a scandal that rocked the British government attends a party in Chelsea 11:9 to launch “Swingin’ Sixties”. David Bailey Penelope Tree Marianne Faithfull

This article is an except from one of the chapters of the thoroughly recommended Beautiful Idiots and Brilliant Lunatics by Rob Baker. We highly advocate buying it!

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.