Indian-born English mericanctress Vivien Leigh (1913 – 1967), who won Academy Awards for her roles in ‘Gone With The Wind’ and ‘A Streetcar Named Desire’. (Photo by Sasha/Getty Images)

Throughout her life Vivien Leigh was considered by most as one of the most beautiful actresses of her day, and for that matter any other day. It was George Cukor, the original director of Gone With the Wind, who said Vivien Leigh was the “consumate actress, hampered by beauty.” When she was once asked, however, if she considered her beauty to have ever been a problem, she said:

People think that if you look fairly reasonable, you can’t possibly act, and as I only care about acting, I think beauty can be a great handicap, if you really want to look like the part you’re playing, which isn’t necessarily like you.

Laurence Oliver who had married Leigh in 1940 in a ceremony in Santa Barbara in California hosted by Ronald and Benita Coleman said that her critics should:

Give her credit for being an actress and not go on forever letting their judgments be distorted by her great beauty.

Garson Kanin, the great screen writer and with Katharine Hepburn a witness to Olivier and Leigh’s wedding, described the Indian-born English actress as:

A stunner whose ravishing beauty often tended to obscure her staggering achievements as an actress. Great beauties are infrequently great actresses – simply because they don’t need to be. Vivien was different; ambitious, persevering, serious, often inspired.

Although well known in Britain it wasn’t until the release of Gone with the Wind in 1939 that Leigh became famous in America and throughout the rest of the world. In December 1939 the New York Times wrote,

Miss Leigh’s Scarlett has vindicated the absurd talent quest that indirectly turned her up. She is so perfectly designed for the part by art and nature that any other actress in the role would be inconceivable.

English actress Vivien Leigh (1913 – 1967). Original Publication: People Disc – HS0069 (Photo by Sasha/Getty Images)

25th January 1935: English actress Vivien Leigh (1913-1967), born Vivien Mary Hartley, the wife of actor Laurence Olivier. (Photo by Sasha/Getty Images)

Kate Shapland, the beauty editor of the Daily Telegraph once described Vivien Leigh simply:

She wore Joy by Patou. She hated her hands. She loved chocolate. She drank martinis and gin and tonic, never tea. She slept no more than six hours a night. She smoked packets of fags. She was good at cards.

Shapland in the same article at salihughesbeauty.com describes her beauty routine:

She knew which lipstick/nail polish nuance it had to be (light), she had the foundation nailed, she didn’t wear powder (she told her daughter, Suzanne, it was ageing), she only wore eyeshadow in the evening, and her naturally curly hair – attempting a break from an otherwise forced look – was straightened every week. Her skincare regime would have been Elizabeth Arden – I can see a pot of Eight Hour Cream on her dressing table; the visits to Arden’s salon in Bond Street, with its crinoline staircase and chinoiserie wallpaper, regular. She never got fat.

25th January 1935: English actress, Vivien Leigh (1913-1967) relaxing at home. (Photo by Sasha/Getty Images)

circa 1940: British actors Vivien Leigh (1913-1967) and Laurence Olivier (1907-1989) entertaining millionaire Sir Victor Sassoon on the set of ‘Waterloo Bridge’, a Metro Goldwyn Mayer film in which Leigh is currently starring. (Photo by Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

Vivien Leigh, 1941 by Cecil Beaton

Vivien Leigh as she appears in ‘Serena Blandish’ at the Gate Theatre. sept 1938 (Photo by Sasha:Getty Images)

Vivien Leigh (1913 – 1967) flirts with the camera, 1935 (Photo by Sasha:Hulton Archive:Getty Images)

Vivien Leigh, Paris, 1952 Photo Willy Rizzo

Vivien Leigh 1940

Leigh on the set of Lady Hamilton 1941

Vivien Leigh as Lady Macbeth, Laurence Olivier as Macbeth, SMT 1955. RSC:Angus McBean

Vivien Leigh, British Embassy, Paris, 1947 Cecil Beaton

Vivien and Larry

Waiting to film the scene when Scarlett visits Rhett Butler in jail on the Gone with the Wind set.

British film stars Laurence Olivier and Vivien Leigh after visiting a London theatre to see a revival of ‘Dear Brutus’. The stars have flown to London from Hollywood to play their part in the war. Olivier hopes to join the RAF and Vivien Leigh is hoping to join a stage company touring Britain. (Photo by George Hales/Getty Images)

English actress Vivien Leigh (1913 – 1967) catches up with some paperwork in her dressing room, 1943. (Photo by Keystone/Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

October 1949: Vivien Leigh toasts the stars in her role as Blanche in ‘A Streetcar Named Desire’, playing at the Aldwych Theatre, London. Picture Post – 4903 – Desire Goes Off The Rails – pub.1949 (Photo by Kurt Hutton/Picture Post/Getty Images)

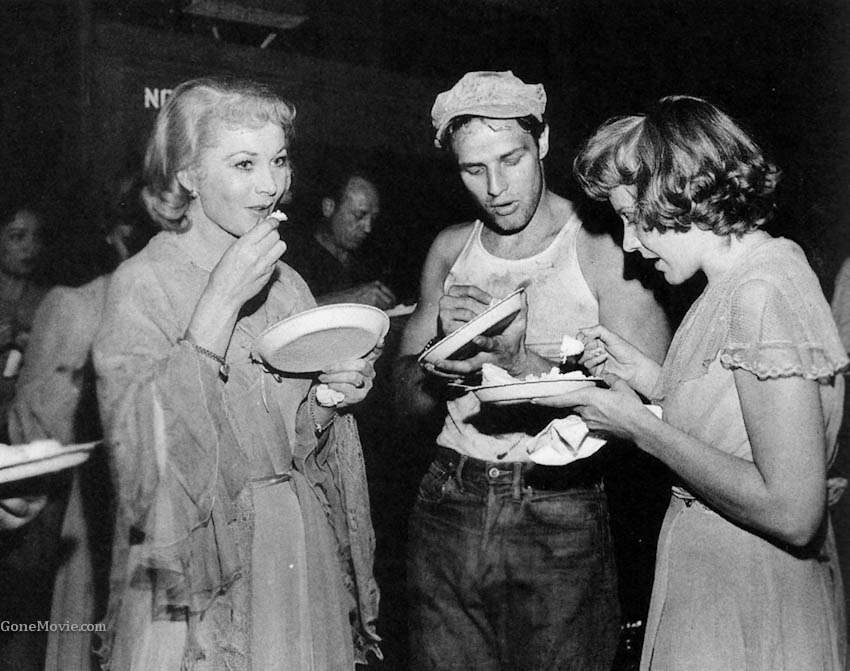

Leigh’s 1949 performance in the West End production of A Streetcar Named Desire was described by the poet and theatre historian Phyllis Hartnell as “proof of greater powers as an actress than she had hitherto shown”. While in the film version of Tennessee Williams’ play that was released in 1951 and directed by Elia Kazan, the critic Pauline Kael wrote that Leigh and Marlon Brando gave “two of the greatest performances ever put on film” and that Leigh’s was “one of those rare performances that can truly be said to evoke both fear and pity.”

Vivien Leigh (Blanche DuBois) lunches with Marlon Brando (Stanley Kowalski) and Kim Hunter (Stella Kowalski).

Actors and spouses Laurence Olivier and Vivien Leigh, posing for a LIFE magazine photographer in their home, Chelsea, London, circa 1950. (Photo by George Konig/Keystone Features/Getty Images)

Beatles drummer Ringo Starr boarding a plane at London Airport (now Heathrow) with actress Vivien Leigh (1913 – 1967), 12th June 1964. Starr is flying to Australia to join the rest of the Beatles on their 1964 world tour. (Photo by George Stroud/Express/Getty Images)

In 1965 Leigh appeared in her last film Ship of Fools. The producer and director Stanley Kramer was initially unaware of the fragile mental and physical health of his star. Later Kramer remembered her courage in taking on the difficult role, “She was ill, and the courage to go ahead, the courage to make the film – was almost unbelievable.” Leigh’s performance was tinged by paranoia and resulted in outbursts that marred her relationship with other actors, although both Simone Signoret and Lee Marvin were sympathetic and understanding. Although during the attempted rape scene, Leigh became particularly distraught and hit Marvin so hard with a spiked shoe, that it marked his face.

In May 1967 Leigh was rehearsing with Michael Redgrave in Edward Albee’s A Delicate Balance when she became ill with tuberculosis. A few weeks later she collapsed one night walking to the bathroom – her lungs filled with liquid. Olivier who was receiving treatment for prostate cancer nearby rushed to Leigh’s residence but could only pay his respects. In his autobiography he described that he: “stood and prayed for forgiveness for all the evils that had sprung up between us”.

On the public announcement of her death on 8 July, the lights of every theatre in central London were extinguished for an hour.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.