Now we will count to twelve

and we will all keep still.

– Pablo Neruda, Keeping Quiet

![Photograph shows Chilean poet Pablo Neruda, seated at a table in front of a microphone in the Library of Congress Recording Laboratory, Studio B, Washington, D.C., during the recording of his poem "Alturas de Macchu Picchu" for the Archive of Hispanic Literature on Tape. Created / Published [Washington, D.C.], [20 June 1966]](https://flashbak.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/neruda-1200x974.jpg)

Chilean Statesman, committed Communist, former enemy of the state and prolific poet of the soul, Pablo Neruda (July 12, 1904–September 23, 1973) wrote the poem Keeping Quiet in the 1950s. Published in Extravagaria (1974), the poem is a message for our time, when so many of us are living in isolation. “There is no insurmountable solitude,” said Neruda as he collected the Noble Prize for literature in 1971. “And we must pass through solitude and difficulty, isolation and silence in order to reach forth to the enchanted place where we can dance our clumsy dance and sing our sorrowful song – but in this dance or in this song there are fulfilled the most ancient rites of our conscience in the awareness of being human and of believing in a common destiny.”

Should we revisit Neruda’s life and artistic worth, given that he admitted to a heinous crime in his autobiography, which was published after his death in Spanish in 1974 and translated into English in 1977? In 1929, Neruda was a diplomat in Ceylon. “I decided to go all the way. I got a strong grip on her wrist and stared into her eyes,” he wrote of the maid who cleaned his quarters. “There was no language I could talk with her. She let me lead her, without a smile, and she was soon naked on my bed. Her skinny waist, her full hips, the brimming cups of her breasts, made her like one of the millennial sculptures from southern India. The encounter was of a man with a statue. Her eyes stayed open the whole time impassible. She was right to despise me. The experience was not repeated.”

In 2018, Chilean legislators voted to rename Santiago airport after Neruda.

“Like many young feminists in Chile I am disgusted by some aspects of Neruda’s life and personality,” said Isabel Allende, the writer and women’s rights campaigner. “However, we cannot dismiss his writing. Very few people – especially powerful or influential men – behave admirably. Unfortunately, Neruda was a flawed person, as we all are in one way or another, and Canto General is still a masterpiece.” Neruda’s poems have been sold in the millions, scattering his poetry like seeds. Each year, thousands of fans make the pilgrimage to see the poet’s homes.

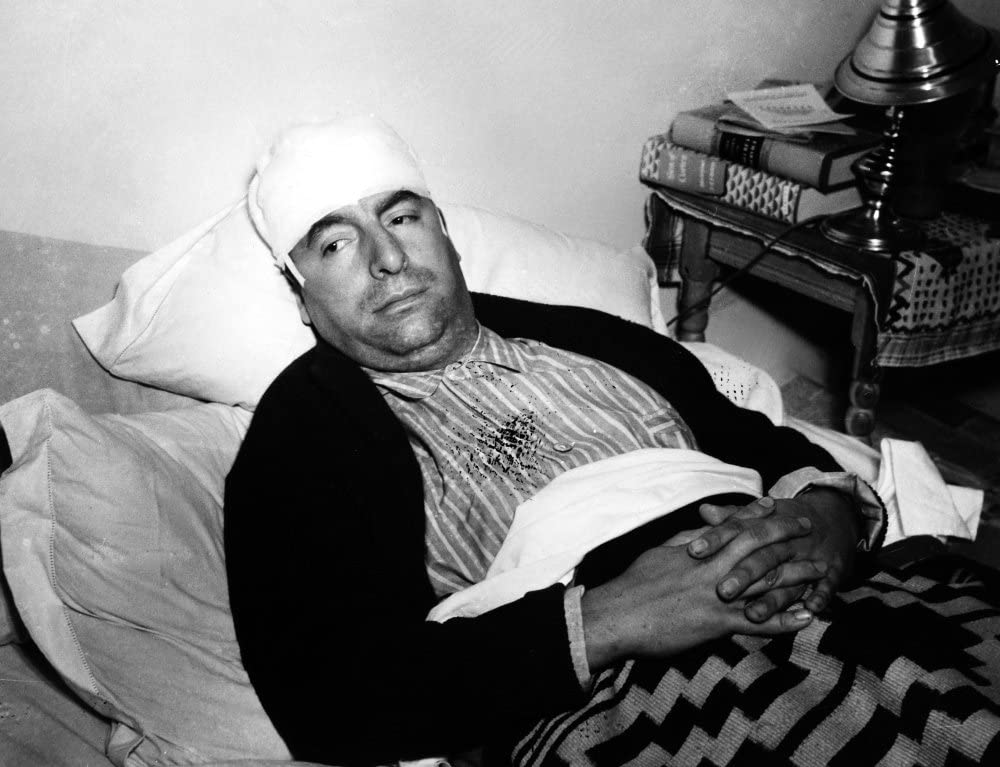

Pablo Neruda (1904-1973). Chilean Poet And Diplomat. Neruda In A Hospital In Mexico City After Being Attacked In A German Restaurant For Toasting President Franklin Roosevelt. Photographed 1948.

What are we left with? The following extract is from Neruda and Vallejo Selected Poems. As a boy Neruda lived in Temuco in Chile’s deep south. His mother died of tuberculosis six weeks after he was born and his father, a train conductor, was fiercely opposed to his literary ambitions. “Poetry came in search of me,” he wrote. He recalled the awakening:

One time, investigating in the backyard of our house in Temuco the tiny objects and minuscule beings of my world, I came upon a hole in one of the boards of the fence. I looked through the hole and saw a landscape like that behind our house, uncared for, and wild. I moved back a few steps, because I sensed vaguely that something was about to happen. All of a sudden a hand appeared — a tiny hand of a boy about my own age. By the time I came close again, the hand was gone, and in its place there was a marvellous white sheep.

The sheep’s wool was faded. Its wheels had escaped. All of this only made it more authentic. I had never seen such a wonderful sheep. I looked back through the hole, but the boy had disappeared. I went into the house and brought out a treasure of my own: a pinecone, opened, full of odour and resin, which I adored. I set it down in the same spot and went off with the sheep…

To feel the intimacy of brothers is a marvellous thing in life. To feel the love of people whom we love is a fire that feeds our life. But to feel the affection that comes from those whom we do not know, from those unknown to us, who are watching over our sleep and solitude, over our dangers and our weaknesses — that is something still greater and more beautiful because it widens out the boundaries of our being, and unites all living things.

That exchange brought home to me for the first time a precious idea: that all of humanity is somehow together…

It won’t surprise you then that I attempted to give something resiny, earth like, and fragrant in exchange for human brotherhood. Just as I once left the pinecone by the fence, I have since left my words on the door of so many people who were unknown to me, people in prison, or hunted, or alone.

Pablo Neruda, poet and then Chilean ambassador to France, talks with reporters in Paris after being awarded the 1971 Nobel Prize for Literature. The Chilean government announced, that it will join the DNA investigation in an effort to discover if he died from prostate cancer as was recorded, or if he was poisoned by agents of Gen. Augusto Pinochet’s dictatorship, as his driver and others believe – 21 Oct 1971

And so to the poem for all times:

KEEPING QUIET

by Pablo NerudaNow we will count to twelve

and we will all keep still.For once on the face of the earth,

let’s not speak in any language;

let’s stop for one second,

and not move our arms so much.It would be an exotic moment

without rush, without engines;

we would all be together

in a sudden strangeness.Fisherman in the cold sea

would not harm whales

and the man gathering salt

would look at his hurt hands.Those who prepare green wars,

wars with gas, wars with fire,

victories with no survivors,

would put on clean clothes

and walk about with their brothers

in the shade, doing nothing.What I want should not be confused

with total inactivity.

Life is what it is about;

I want no truck with death.If we were not so single-minded

about keeping our lives moving,

and for once could do nothing,

perhaps a huge silence

might interrupt this sadness

of never understanding ourselves

and of threatening ourselves with death.

Perhaps the earth can teach us

as when everything seems dead

and later proves to be alive.Now I’ll count up to twelve

and you keep quiet and I will go.

Lead image: Photograph shows Chilean poet Pablo Neruda, seated at a table in front of a microphone in the Library of Congress Recording Laboratory, Studio B, Washington, D.C., during the recording of his poem “Alturas de Macchu Picchu” for the Archive of Hispanic Literature on Tape – 20 June 1966.

Via: Brain Pickings

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.