I slept and dreamt

that life was joy.

I awoke and saw

that life was duty.

I worked — and behold,

duty was joy.– Rabindranath Tagore

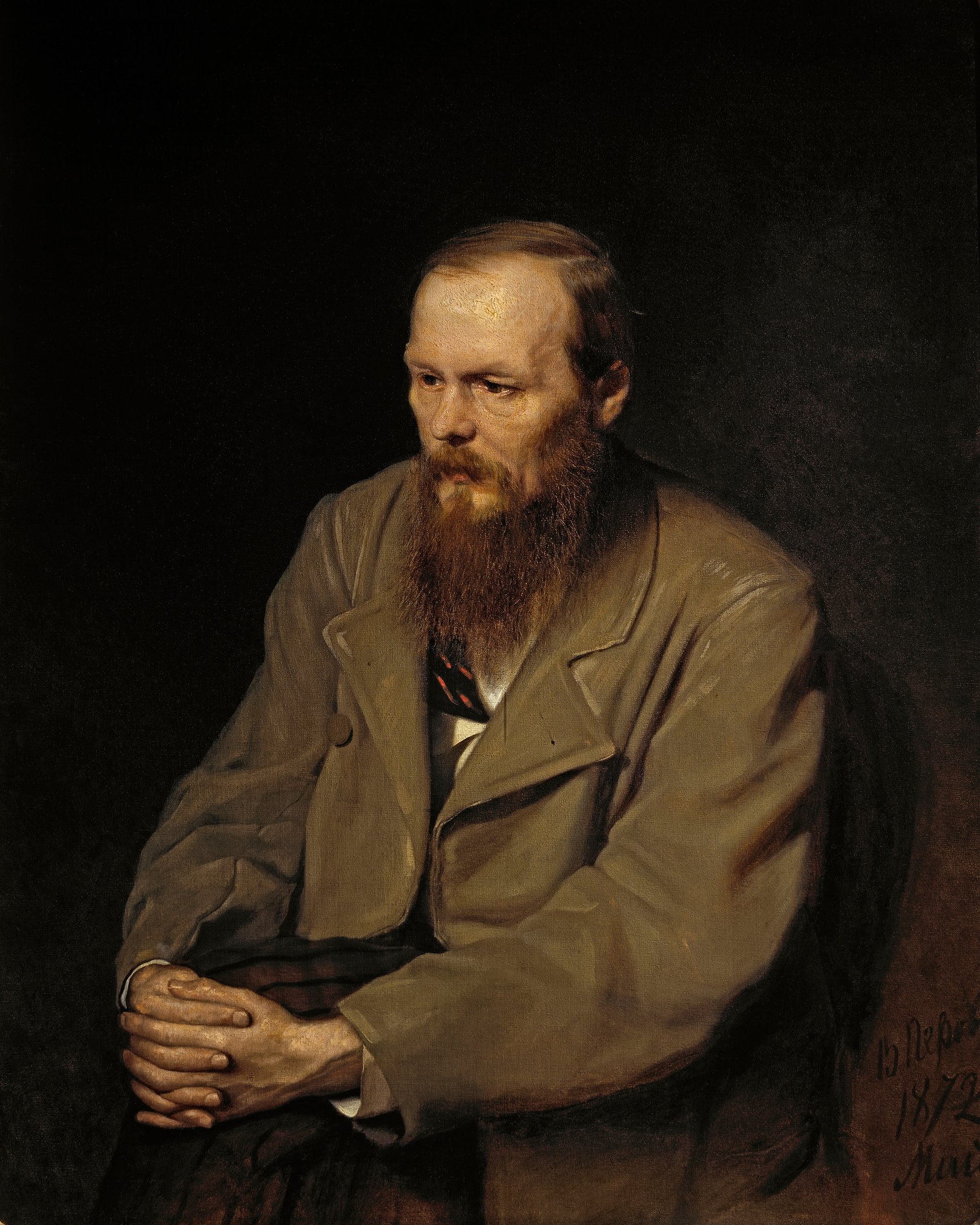

Russian writer Fyodor Dostoyevsky (November 11, 1821–February 9, 1881) knew the time of his death. Arrested in April 1849 for belonging to a literary society that discussed banned books critical of Tsarist Russia, Dostoyevsky would die on on December 22, 1849, in a public square in Saint Petersburg.

He and other enemies of society were read the death sentence, dressed in white shirts, allowed to kiss the cross and made to stand still as sabres were broken over their heads. Then three at a time, they were lined up against the stakes and presented to the firing squad. Sixth in line, Dostoyevsky would witness three executions before it was his turn to die. But then came a reprieve. The tsar had decided to spare him. A new declaration was read aloud. Instead of swift death, Dostoyevsky was to pass four years in a Siberian labour camp, followed by many years of compulsory military service in the tsar’s armed forces in exile.

A life of sorts. But was it one worth living?

Fellow writer Walt Whitman’s remedy for living a half-life was “to tone your wants and tastes low down enough, and make much of negatives, and of mere daylight and the skies.” But Whitman, was 64 years old when he wrote that and by his own admission, “The principal object of my life seems to have been accomplish’d.” For him, the past had taken on a sort of privileged appearance. Just last week you had more future, but today you have less.

But no compelling and effervescent a writer as Whitman or Dostoyevsky wants to depress their reader. It’s not death they’re interested in, it’s living, to make the extraordinariness of human life vivid. It’s EM Forster’s epigram: “Death destroys a man; the idea of death saves him.” Facing death, you see life. The stillness, when sentience and time are done, serving as a place from which to see life better.

Composer and philosopher John Cage voiced another way to get through life with authenticity and integrity: “No why. Just here.”

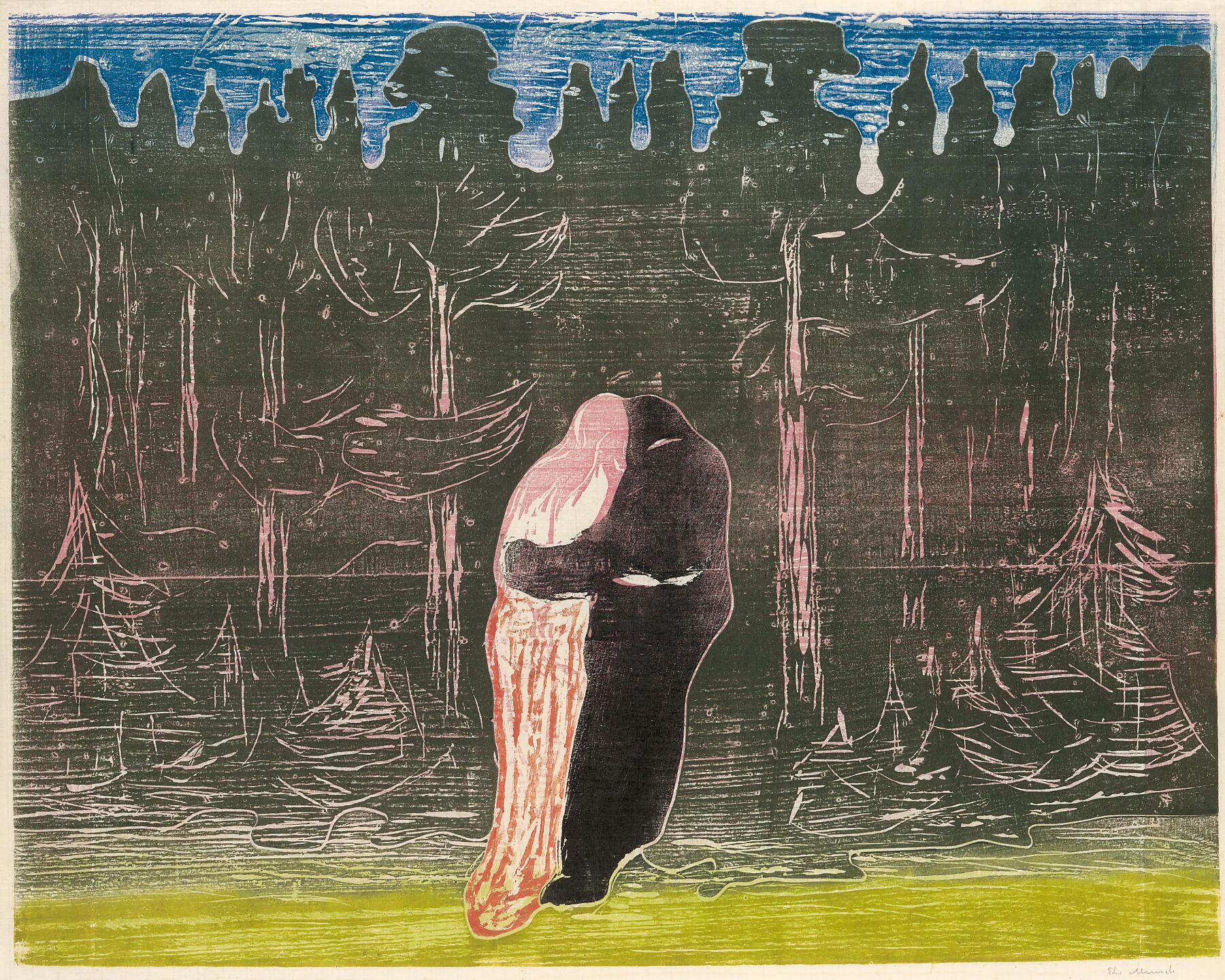

Edvard Munch : bokmål- Mot skogen II (English: Towards the Forest II) – 1915 – Buy Print

How would Dostoyevsky live in chains, his hands and feet tethered in prison; his library comprised of the only book permitted, a copy of the New Testament? Could the artist remain truly conscious in such a place? Hours after the tsar’s stunt, he wrote to his brother Mikhail (via Dostoevsky Letters):

Brother! I’m not despondent and I haven’t lost heart. Life is everywhere, life is in us ourselves, not outside. There will be people by my side, and to be a human being among people and to remain one forever, no matter in what circumstances, not to grow despondent and not to lose heart – that’s what life is all about, that’s its task. I have come to recognize that. The idea has entered my flesh and blood…

The head that created, lived the higher life of art, that recognized and grew accustomed to the higher demands of the spirit, that head has already been cut from my shoulders…

But there remain in me a heart and the same flesh and blood that can also love, and suffer, and pity, and remember, and that’s life, too!

Be in Love and You will be Happy (Soyez amoureuses, vous serez heureuses) by Paul Gaugin -1895 – buy Print

Years later, in a letter of February of 1876, he reiterated his sense of purpose, as being, “A true friend of mankind whose heart has but once quivered in compassion over the sufferings of the people, will understand and forgive all the impassable alluvial filth in which they are submerged, and will be able to discover the diamonds in the filth.”

As intermingling, social selves, we acquire meaning for others. One story has it that on the way to prison, Dostoevsky consoled the other prisoners, such as the Petrashevist Ivan Yastrzhembsky, who, surprised by Dostoevsky’s kindness, abandoned his decision to kill himself.

But in 1849, Dostoyevsky was still a young man, and the letter his mind pings between despondency, resignation and hope:

“Can it be that I’ll never take pen in hand? If I won’t be able to write, I’ll perish. Better fifteen years of imprisonment and a pen in hand!”

…

I haven’t lost heart, remember that hope has not abandoned me… After all I was at death’s door today, I lived with that thought for three-quarters of an hour, I faced the last moment, and now I’m alive again!

And then resignation, followed by the acceptance of being:

If anyone remembers me with malice, and if I quarrelled with anyone, if I made a bad impression on anyone — tell them to forget about that if you manage to see them. There is no bile or spite in my soul, I would like to so love and embrace at least someone out of the past at this moment.

…

When I look back at the past and think how much time was spent in vain, how much of it was lost in delusions, in errors, in idleness, in the inability to live; how I failed to value it, how many times I sinned against my heart and spirit — then my heart contracts in pain. Life is a gift, life is happiness, each moment could have been an eternity of happiness. Si jeunesse savait! [If youth knew!]

Dostoyevsky adds:

Now, changing my life, I’m being regenerated into a new form. Brother! I swear to you that I won’t lose hope and will preserve my heart and spirit in purity. I’ll be reborn for the better. That’s my entire hope, my entire consolation.

Life in the casemate has already sufficiently killed off in me the needs of the flesh that were not completely pure; before that I took little care of myself. Now deprivations no longer bother me in the slightest, and therefore don’t be afraid that material hardship will kill me.

Via: Spiked, Brain Pickings, Anorak

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.