Leonid Breshnez (General Secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union):

“We members of the Politburo are here sitting and watching what you are doing. We are proud of you”

Alexei Leonoz (Cosmonaut):

“I’m feeling perfect”

But 311 miles above Earth, travelling at 19,000mph, things were about to go badly wrong for Alexei Leonov.

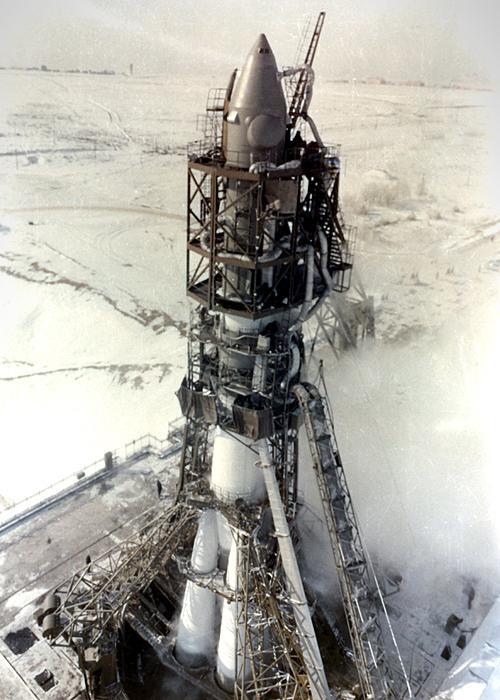

Archived image from the FAI report certifying the first spacewalk by Russian cosmonaut Alexei Leonov on March 18, 1965. (FAI)

On 18 March 1965, Alexei Leonov did become the first person to walk in space. He slid from the Voskhod-2 (Sunrise-2) capsule, and for 12 minutes and 9 seconds floated in the great beyond. Leonov was 500km above Earth, attached to the rest of humanity by a 5.35-meter umbilical cord.

The 30-year-old cosmonaut had trained alongside his friend and space pioneer Yuri Gagarin, who in April 1961 had become the first man in space. Leonov should have been well prepared for his adventure. He wasn’t. He would later tell a government committee pushing for a lengthy report into his mission: “If a man has a proper suit and proper training, he is able to work in open space.”

But there he was high above the world with neither.

Alexi Leonov looked down at the Earth. He saw the colours and the lights. “You just can’t comprehend it,” he said. “Only out there can you feel the greatness – the huge size of all that surrounds us… My feeling was that I was a grain of sand.”

A keen artist, Leonov took along some color pencils and paper, illustrating the spectacular view.

First drawing in space and the Taktika pencils used by Alexei Leonov on board Voskhod 2 spacecraft, Museum of the Yuri Gagarin Cosmonaut Training Centre

Leonov’s mission was to trump the Americans and become a Hero of the Soviet Union (something he achieved twice over). To prove that the space walk had taken place, a camera was needed to film the action. Leonov’s art would not be enough to convince the naysayers. He was tasked with attaching one camera to the airlock. A second camera on his chest would record his point-of-view. The pictures would confirm Soviet supremacy.

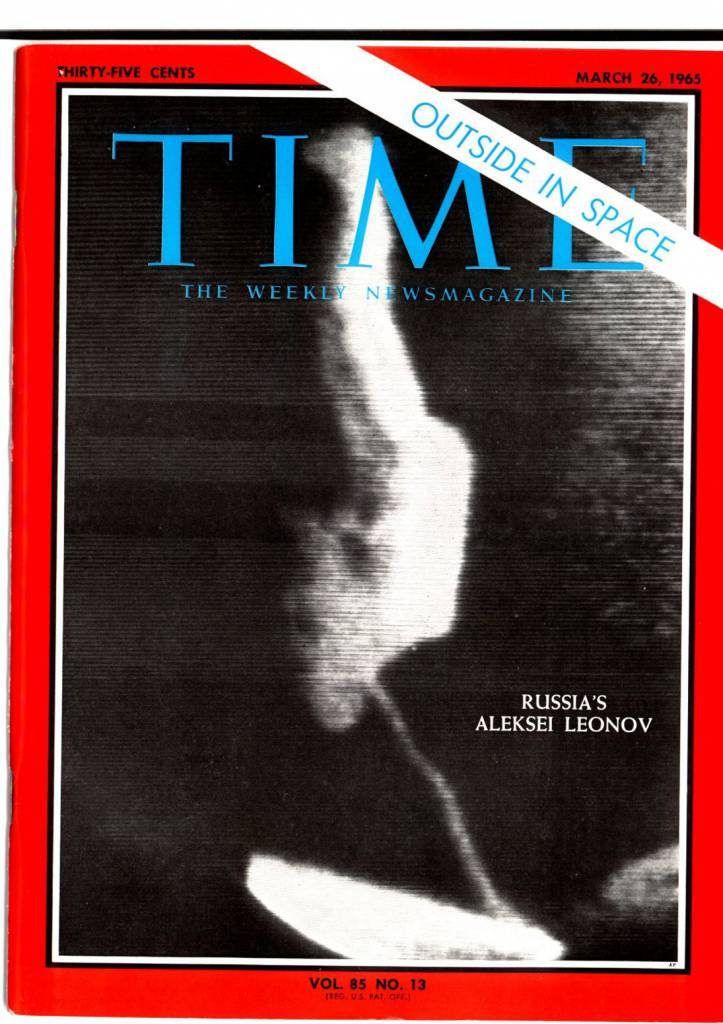

America was watching. Only two and half months later, Ed White became the first American to walk in space. The Soviets were in a hurry. And so on March 26, Alexei Leonov found himself way up there. The moment was huge. TIME magazine thrilled its readers with a cover story of derring-do and terror:

“As air escaped from the [spacecraft’s air lock], the vacuum of space reached into it like a monster’s claw. Though it must have been rehearsed on earth over and over again, this was surely a moment of hideous crisis.”

TIME’s story was not about praising the enemy’s bravery. Having peered into the cosmonaut’s mind and found only “crisis”, the magazine churlishly noted the inferior quality of the images – “dim and probably purposely fuzzy.” Just look at the picture they chose to be on that cover:

This was the Cold War. TIME was a US magazine, its sensibilities firmly in the US camp. Facts arrived from Soviet HQ. What could not be known was guessed at. For instance, TIME told its readers: “Then, as easily and efficiently as he had emerged from his ship, Leonov climbed back inside.”

Not exactly. Not at all. Leonov was in serious trouble. He couldn’t get back inside the capsule.

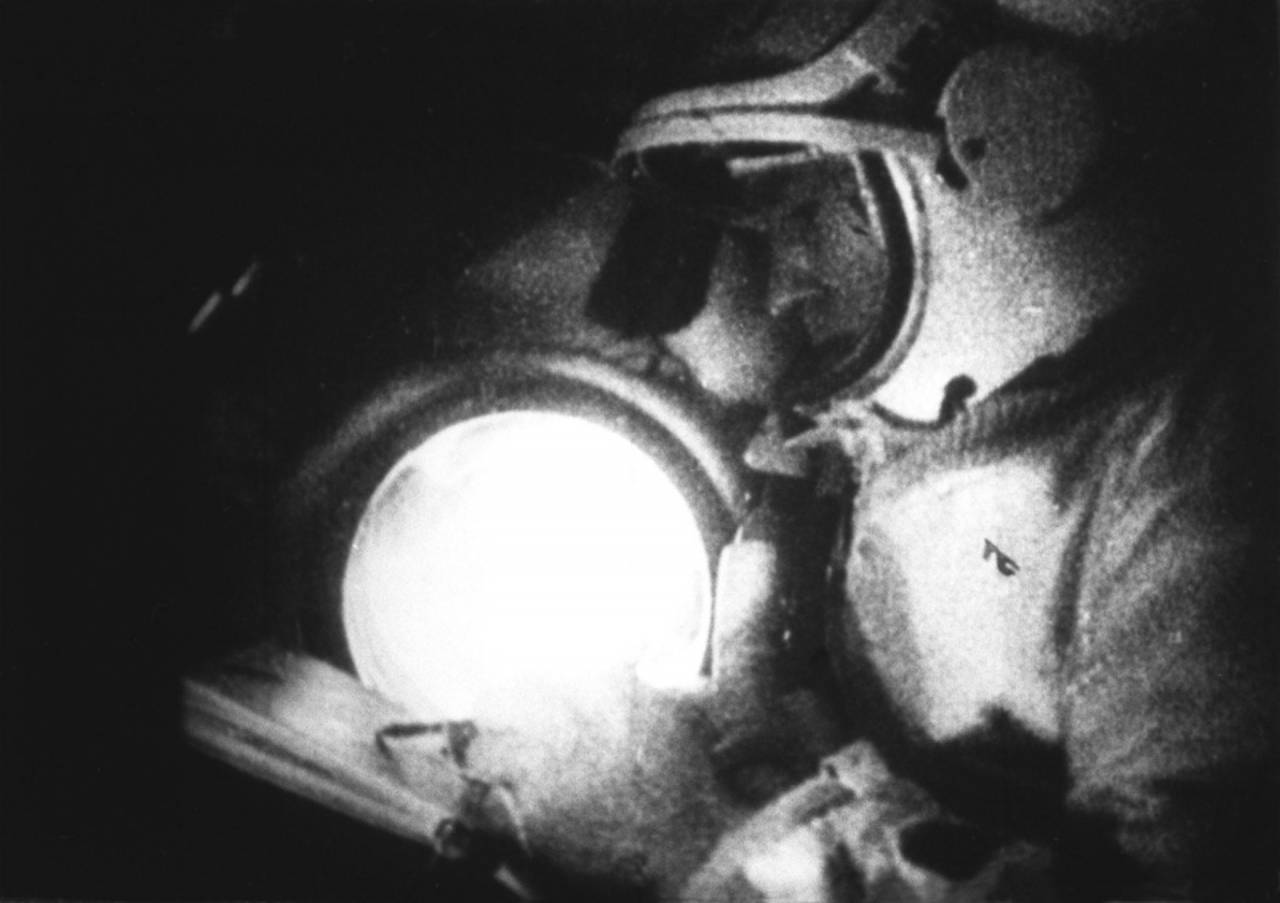

18th March 1965: Russian astronaut Alexei Arkhipovich Leonov becomes the first man to walk in space, during the 26 1/2 hour orbit of the spacecraft Voskhod 2. (Photo by Central Press/Getty Images)

Leonov wrote in 2005:

“As I pulled myself back toward the airlock, I heard Pasha [his crewmate, Pavel (Pasha) Belyayev], talking to me: ‘It’s time to come back in.’ I realized I had been floating free in space for over 10 minutes. In that moment my mind flickered back for a second to my childhood, to my mother opening the window at home and calling to me as I played outside with my friends, ‘Lyosha, it’s time to come inside now.'”

Getting out of the small spaceship had been relatively easy. Leonov crawled into an airlock. He waited for the air pressure to equalize. Then he had slid outside. But Leonov’s inflated spacesuit had ballooned and stiffened. His hands had slipped out of his gloves. He could not pull himself along the tether towards the capsule. He could not get back through the 1.2-meter-wide airlock.

“My suit was becoming deformed. My hands had slipped out of the gloves [and] my feet came out of the boots. The suit felt loose around my body. I had to do something. I couldn’t pull myself back using the cord. And what’s more, with this misshapen suit, it would be impossible to fit through the airlock.”

Drenched in sweat, Leonov went radio silent, deciding not to speak lest the Americans were listening in. If he died, he would not do so publicly.

A sequence of pictures showing Alexei Leonov during the first space walk performing a somersault at the end of the tether that connects him to the capsule.

Soviet cosmonaut Lt. Col. Alexei Leonov, figure at left, leaves spaceship Woskhod – 2 to become the first man to step into outer space. Projection on right holds movie camera. This photo was taken in Moscow off Russian television. Moscow radio reported night that the spaceship had reappeared over Soviet Territory, indicating it had completed 13 orbits.

Leonov explained that he was not alone in keeping up appearances:

“From the moment our mission looked to be in jeopardy, transmissions from our spacecraft, which had been broadcast on both radio and television, were suddenly suspended without explanation. In their place Mozart’s Requiem was played again and again on state radio.”

Things were getting increasingly desperate. The walk was scheduled to pass in sunlight. But in five minutes, the spaceship would move into total darkness.

“The silence struck me. I could hear my heart beating so clearly. I could hear my breath – it even hurt to think. The heavy breaths were looped via microphones and broadcast to Earth.” (The sound of his breathing was recorded, and later looped into the soundtrack of 2001: A Space Odyssey.)…

“I don’t remember anything as well as I remember the sound – this remarkable silence. You can hear your heart beat and you can hear yourself breathe. Nothing else can accurately represent what it sounds like when a human being is in the middle of this abyss.”

Soviet cosmonauts Pavel Belyayev and Alexei Leonov in a gym undergoing physical training for the mission in 1965.

Leonov knew he had to act. He opened a valve to release oxygen, depressurizing his suit until he could fit back into the spacecraft. He had only had 60 liters of air for ventilation. Being low on oxygen carried risks. Would he black out? “I began to get pins and needles in my legs and hands,” Leonov recalled. “I was entering the danger zone, I knew this could be fatal.”

Leonov was enduring a terrifying psychological test. He was physically strong – every day he had run a minimum of 5km and swam 700m – but would his mind let him down?

Space travel exposed the body to high G-forces. So the trainees were spun round in centrifuges, sometimes until they passed out. They were also locked in a sensory deprivation chamber. But the room’s oxygen-rich atmosphere made it dangerously flammable inside.

In 1961, Valentin Bondarenko accidentally dropped a piece of alcohol-soaked cotton wool on to a hot plate while training in the chamber. He was engulfed in a fireball, dying in hospital hours later from horrific injuries.

After that, engineers switched to using normal air.

In early 1963, the cosmonauts received a summons to OKB-1, the main centre in Moscow for designing and building spaceships. They were invited to visit by Sergei Korolev, the mastermind behind the USSR’s space programme.

The spacecraft looked similar to the space vessels that Gagarin and other cosmonauts had flown in. But one of them was different. It was fitted with a transparent tube about 3m long and 1.2m wide – an airlock. As the curious cosmonauts gathered round this unusual vehicle, Korolev addressed them: “A sailor must be able to swim in the sea. Likewise, a cosmonaut must be able to swim in outer space.”

Then he singled out Leonov and told him: “You, little eagle, put on that suit.”

So there he was, floating miles above home, locked inside a baggy, failing life-support system.

Soviet cosmonauts alexey leonov (right) and pavel belyayev in the cabin of the voskhod 2 spacecraft prior to take-off, 1965.

Leonov was supposed to re-enter the airlock feet first. He crept in head first. This meant turning around in a tiny space. And then he had to pull the tether inside. “It was the most difficult thing: I’m in this suit and I had to turn around in the airlock,” he recalled. “But with the perspiration, I couldn’t see anything.”

Inside the thin-metal capsule, Belyayev, a former World War 2 fighter pilot, was waiting. Leonov took the seat besides his friend. And then the tin can began to rotate. Ejecting the inflatable airlock had sent the spacecraft into a spin. The immense G-forces caused blood vessels in both men’s eyes to rupture. A mechanical error sent oxygen levels climbing. The place was highly flammable. The cosmonauts knew the dangers. “A spark would have caused an explosion and we would have been vaporized,” said Leonov.

Belyayev and Leonov worked to lower the temperature, increasing the humidity to reduce the risk of fire. And that’s when the automatic guidance system failed.

How they could return safely to Earth? They had flown much higher than planned. Leonov told RT:

“I keep going over the mission and I keep finding mistakes that could have been avoided. They could have led to tragedy, everything was on the edge. We were thrown to an altitude of 495 kilometers by an error, it [was]…200 kilometers higher than planned. And it so happened that we were flying some 5 kilometers below the radiation layer.”

They needed power. The pilots would have to fire the guidance rockets manually.

If the burn was too short, the Voskhod 2 would hit the atmosphere at too shallow an angle, bouncing back into space. But if the burn continued for too long, it would come down at too steep an angle. This would cause it to plummet at much too high a speed and be destroyed. With the right burn duration, at the right time, the capsule would plunge through the atmosphere on a trajectory that would bring it down safely. The rocket firing went well, but the cosmonauts had little control over where they would land.

Leonov:

“As our orbit brought us above the Crimea, we received the first ground control communication we’d had in some time. “How are you, Blondie? Where did you land?” It was Yuri Gagarin; he always called me ‘Blondie’. It was good to hear his voice. Even in such difficult circumstances he sounded full of warmth, even relaxed. But from what he was saying, it was clear mission control thought we had already landed.

“Pasha clicked on his microphone. We had to turn off the automatic landing system. We have only enough fuel to do one correction, and besides that, the indicator shows that the main engine for reentry is very low on fuel, Pasha reported in as steady a voice as he could: ‘We can make only one attempt at reentry. We are asking you therefore to go into emergency mode.'” …

“Pasha began orienting the craft for reentry. This was no easy task. In order to use the optical device necessary for orientation, he had to lean horizontally across both seats in the spacecraft, while I held him steady in front of the orientation porthole. We then had to maneuver ourselves back into the correct positions in our seats very rapidly so that the spacecraft’s center of gravity was correct during the reentry burn. As soon as Pasha turned on the engines we heard them roar and felt a strong jerk as they slowed our craft. According to the flight schedule, our landing module would separate from the orbital module 10 seconds after retro-fire. I counted the seconds down in my head.”

“But something was very wrong. It felt as if we were being dragged from behind, as if something was pulling us back. When we began to reenter the Earth’s atmosphere, we started to feel gravity pulling us in the opposite direction. The conflicting forces—my instruments indicated 10 Gs – were so strong that some of the small blood vessels in our eyes burst. Looking out my window, I realized with horror what was happening. A communication cable connected the landing module with the orbital module, and as we rapidly entered the denser Earth atmosphere, the cable had become the two modules’ common center of gravity, and we were spinning around it.

“The spinning eventually stopped at an altitude of about 100 kilometers, when the connecting cable burnt through and our landing module slipped free. Then we felt a sharp jolt as first the drogue chute and then the landing chute deployed. Everything became very peaceful, very calm. We could hear and feel the wind whistling in the straps as the module swung gently on the landing chute.

“Suddenly everything became dark. We had entered cloud cover. Then it grew even darker. I started to worry that we had dropped into a deep gorge. There was a roaring as our landing engine ignited just above the ground to break the speed of our descent. Finally we felt our spacecraft slumping to a halt. We had landed in two meters of thick snow.”

Twenty-six hours and 2 minutes after launch, the intrepid explorers were back on Earth. Leonov recalls the landing:

“We landed and opened the hatch. The air was cold, it rushed in. We set up our radio channel and began to broadcast our coded signal. Only after seven hours did a monitoring station in West Germany report that they had heard the coded signal which I had sent.”

There were no cheering crowds. But there were wolves and bears. It was March, mating season, when the animals were at their most aggressive.

“After a few more hours, the cosmonauts heard the unmistakable thud of helicopter blades. They walked to a clearing, where they saw that it was a civilian chopper. The pilot and crew were keen to rescue them, throwing down a rope ladder. But it was too flimsy for Leonov and Belyayev to climb in their heavy spacesuits. They declined the offer.

“The helicopter crew must have told others of the men’s whereabouts. As other aircraft began to circle above them, crews threw all kinds of items out for the cosmonauts: a bottle of cognac – which smashed the instant it hit the snow – a blunt axe and warm clothes, most of which got caught in the branches of the tall trees.”

Would they survive? Leonov notes:

“Even though mission control had no idea where we were or whether we had survived, our families were informed that we had landed safely and were resting in a secluded dacha before returning to Moscow. Our wives were advised to write us letters welcoming us home.”

But this was no holiday in a bucolic cottage:

As it got dark, the cosmonauts realised they would have to wring the moisture out of their suits to avoid frostbite. Leonov had perspired so much on the spacewalk that his sweat was now sloshing around in the suit, up to his knees. There was no way to cover the hatch opening, so they would have to cope as best they could as temperatures dropped to -25C.

Leonov heard the rescue party:

“They landed 9km away and came on skis. They made a little hut for us and brought us a big cauldron which we filled with water and put over a fire. Then we washed in it.”

One day later, Belyayev and Leonov skied 9km journey to a clearing where a helicopter was waiting. They were in the air once more, now flown to to fly them to the city of Perm and then on to Baikonur.

Leonov was debriefed. Why had he released air form his suit? It was, after all, against the rules. He answered:

“What would you have done if I’d told you? You would have created a commission. The commission would have selected a chairman, and the chairman would talk to me. I knew I only had 30 minutes left and I didn’t want ground control to panic.”

One legacy of the mission is Leonov’s art. It only takes a moment for him to be back in space:

“I close my eyes and I see the entire Black Sea, the Crimean Peninsula. This is not a map, it’s what I saw. I can take a pencil now and draw it, because I remembered it for the rest of my life. I looked up and there was the Baltic Sea, Gulf of Kaliningrad. I spent my adolescence at the Gulf of Kaliningrad. It was so unusual.”

Alexei Leonov: My 30, 1934 – October 11, 2019.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.