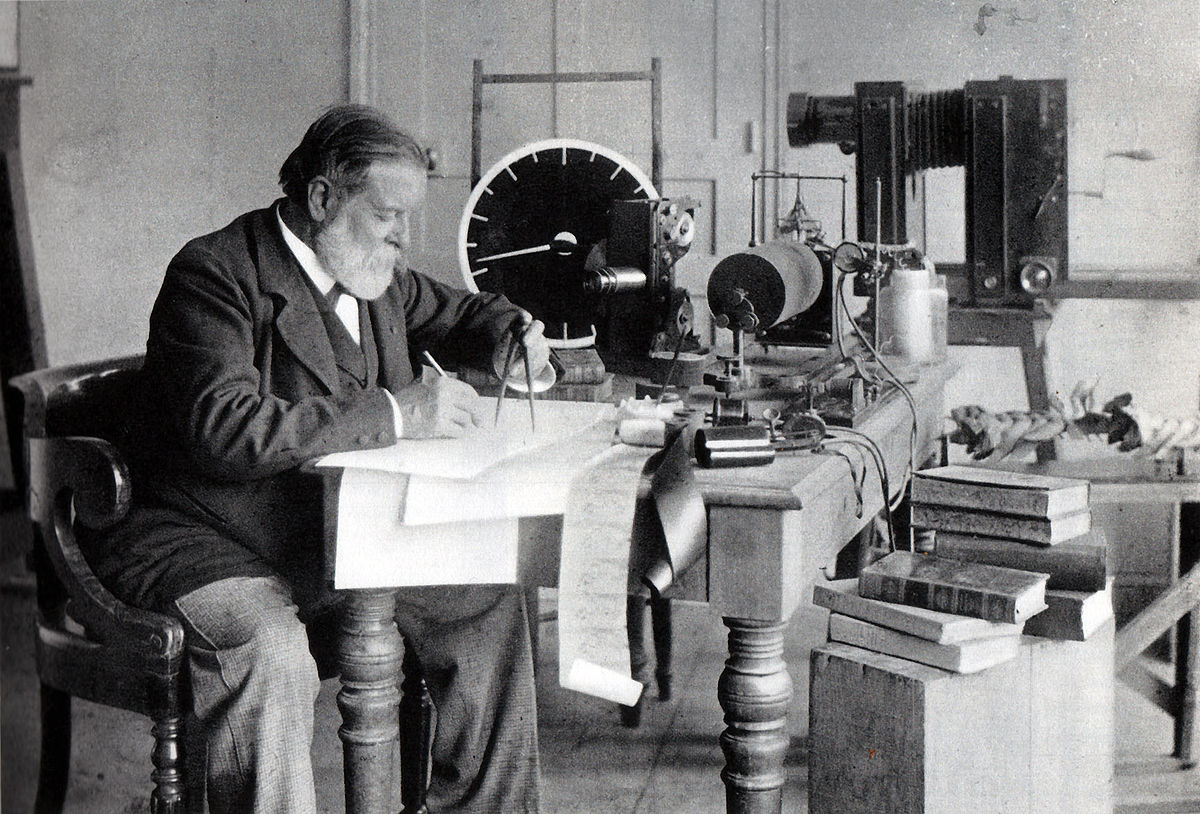

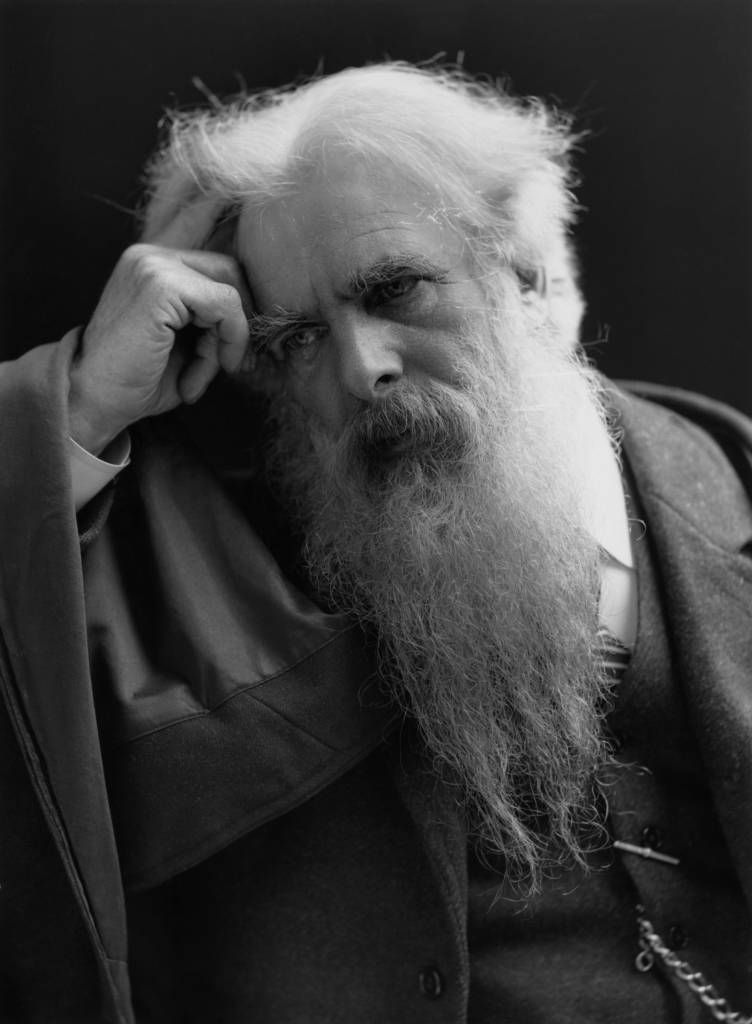

Marey Among His inventions (sphygmograph, sound-recording instruments, model of bird-flight, projector, camera)

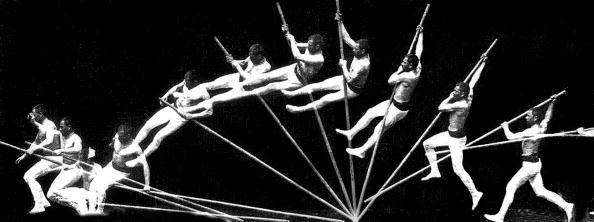

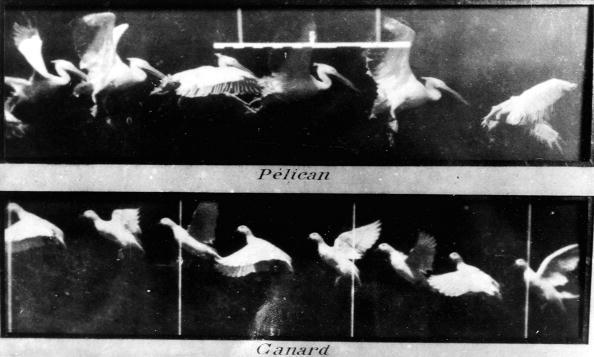

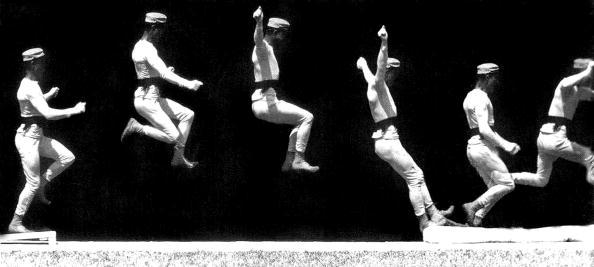

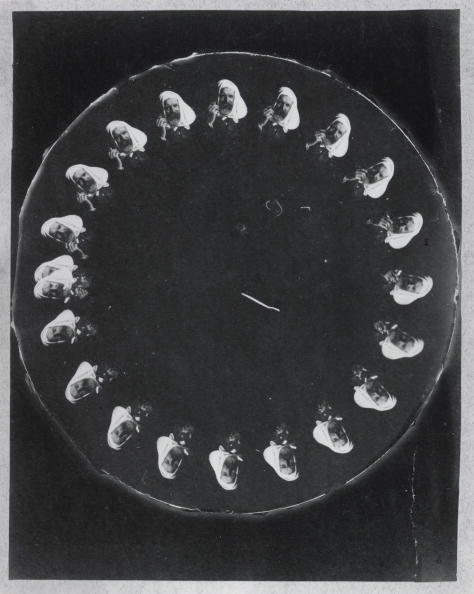

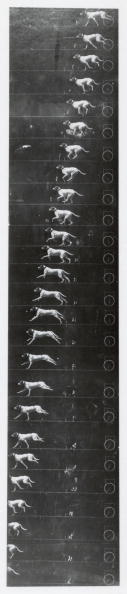

French physiologist Étienne-Jules Marey’s photo gun (1882) enhanced his reputation in chronophotography, in which several sequential frames of movement can be presented in a single image. Marey’s chronophotographic gun could record 12 consecutive frames per second.

You can only represent movement in film via a series of static images. Maray’s rapid-fire photography let us see a rhythm, allowing minds to invest in the illusion, filling in the gaps and creating pattern and trajectory.

Marey’s was hugely influential over painters, who could now see where they had gone wrong with depictions of life on the move.

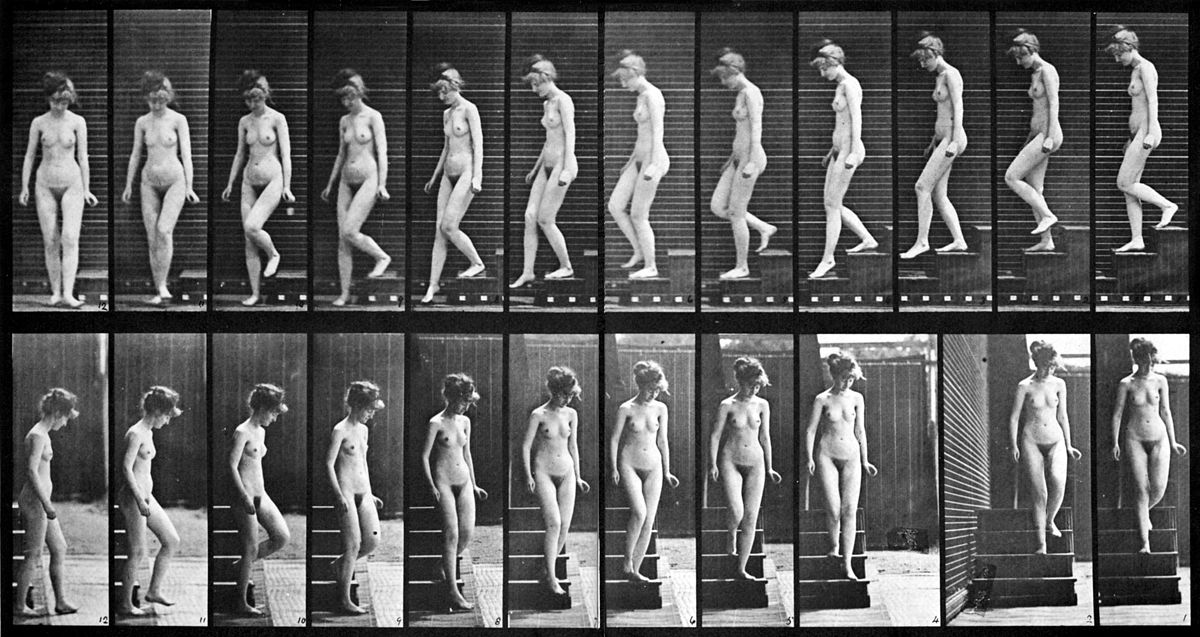

Marey – descending stairs via

Marcel Duchamp could not have produced Nude Descending the Stairs without first studying Marey’s work.

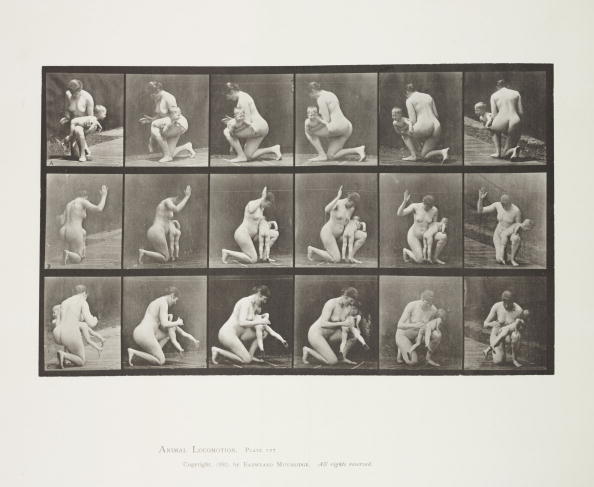

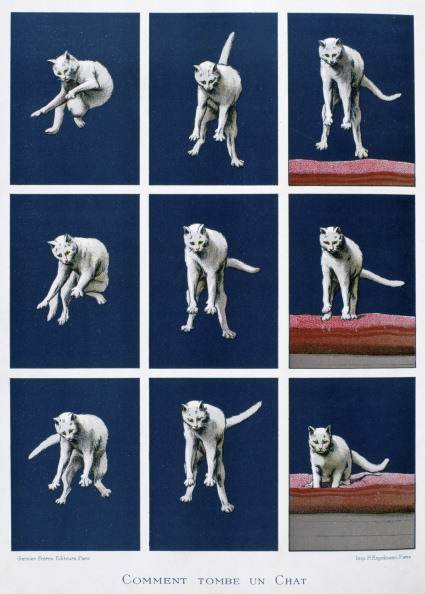

Marey was interested in all movement: animal and human locomotion, blood circulation, displacement of objects and fluids, gravity.

He did not work in isolation. John H. Lienhard writes:

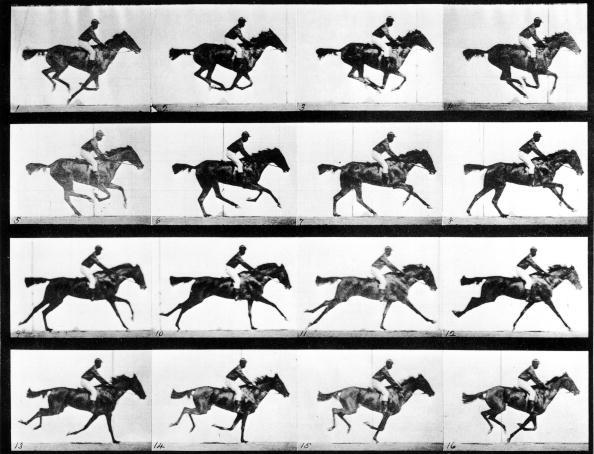

It all began with horses… we still didn’t know if all four hooves simultaneously left the ground in a gallop. The motion was too fast for our eyes. Not even still photography had answered that question. Leland Stanford, Governor of California and horse breeder, had been reading brilliant work on animal and human motion by a French physician named Etienne-Jules Marey.

In 1872 he hired an eccentric photographer, Eadweard James Muybridge, to analyze his horses’ movements.

Muybridge was born and died within weeks of Marey. He had the same initials. Maybe their lives were destined to interweave. But for now, Muybridge struggled to photograph horses. In 1874 he found his wife was having an affair, and he murdered the lover. The jury called it justifiable homicide, and Muybridge left until the smoke cleared.

English photographer Eadweard Muybridge (1930 – 1904), circa 1900. (Photo by Rischgitz/Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

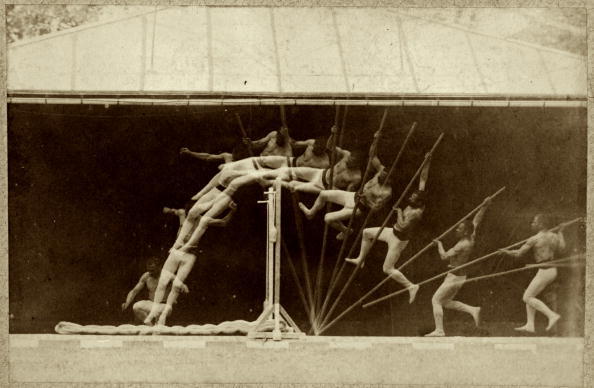

When he came back in 1876, Stanford suggested he gallop horses past a row of cameras equipped with trip wires. When Muybridge did, he got a series of 12 shots in less than half a second. Sure enough, all four hooves really do leave the ground.

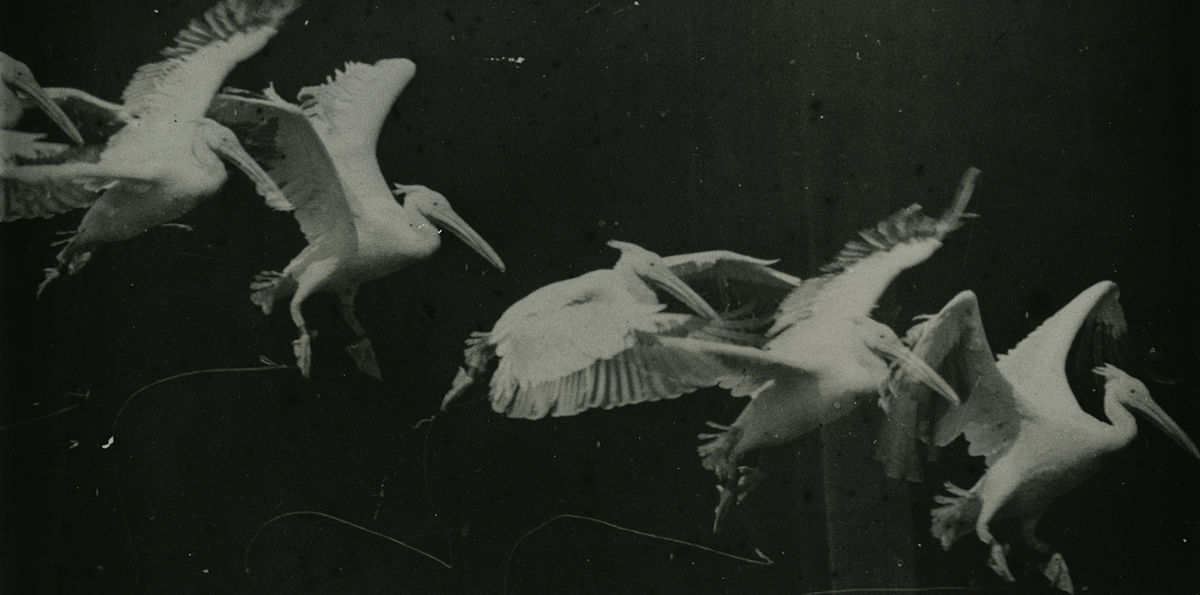

Back in France, Marey was ecstatic when he saw Muybridge’s photos. Muybridge visited Marey in 1881, and Marey said, your horses are wonderful. Can you do birds as well? Muybridge tried, but he could not. So Marey went at the problem himself.

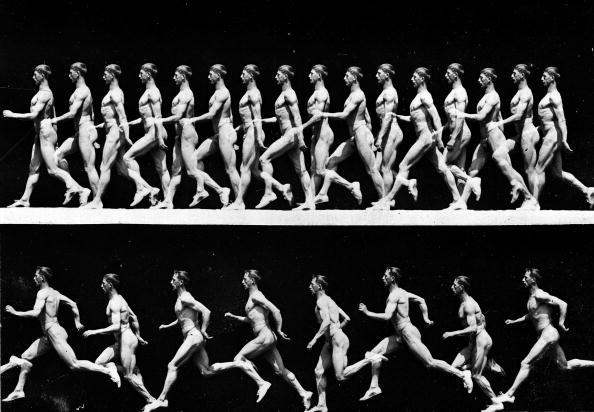

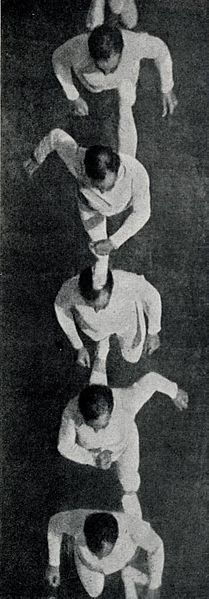

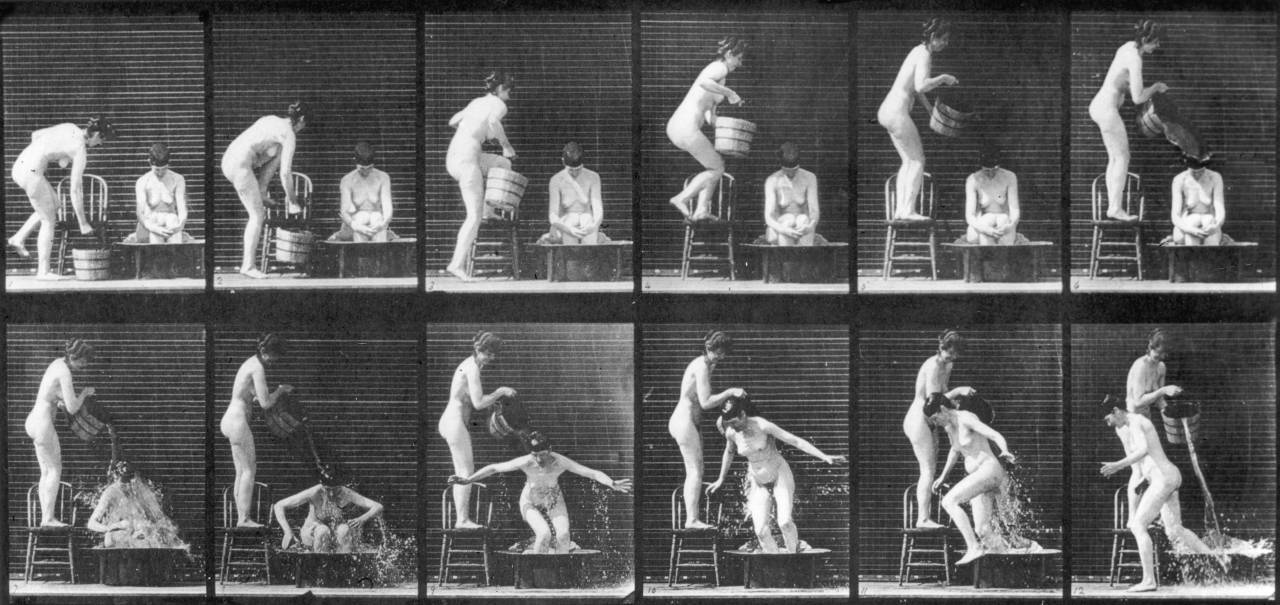

He did, however, like Marey, have more success with nudes.

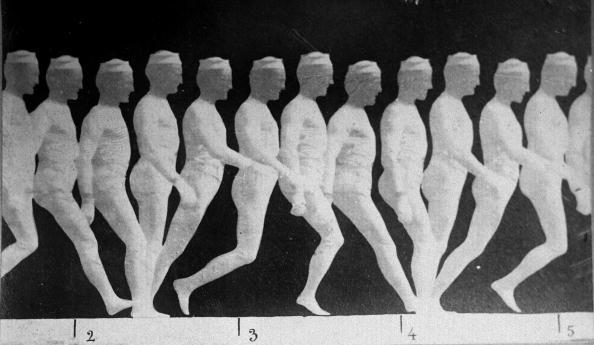

circa 1885: A series of experimental pictures demonstrating Eadweard Muybridge’s theory of human locomotion. (Photo by Eadweard Muybridge/Getty Images)

Marey set to work.

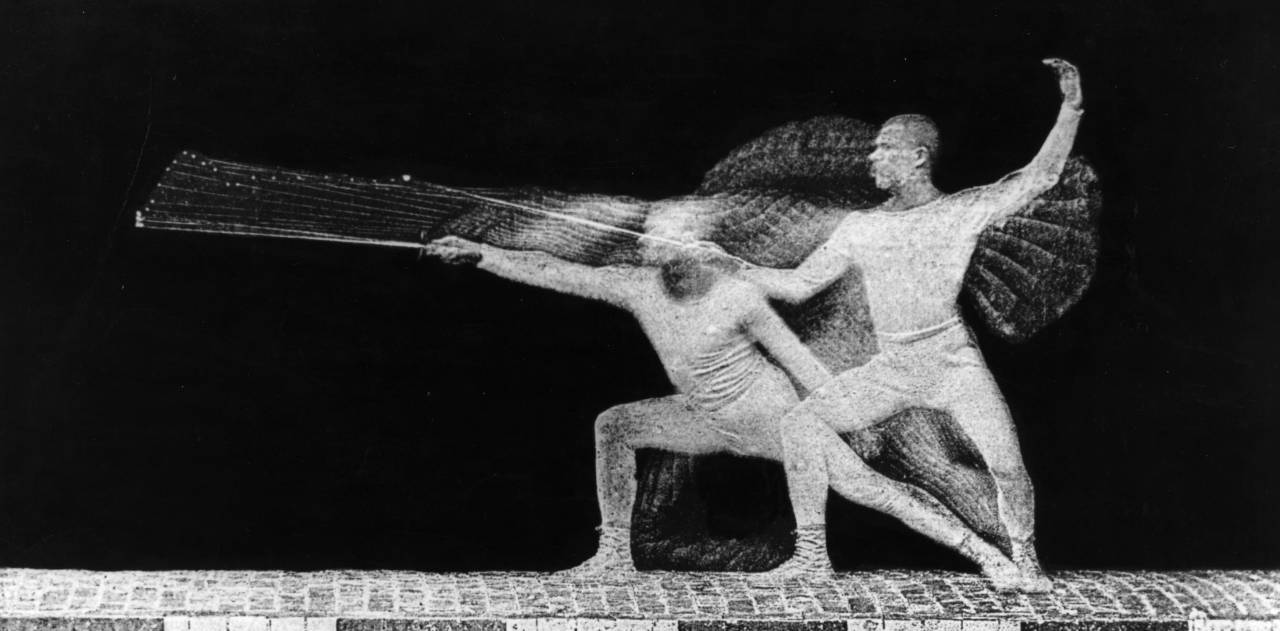

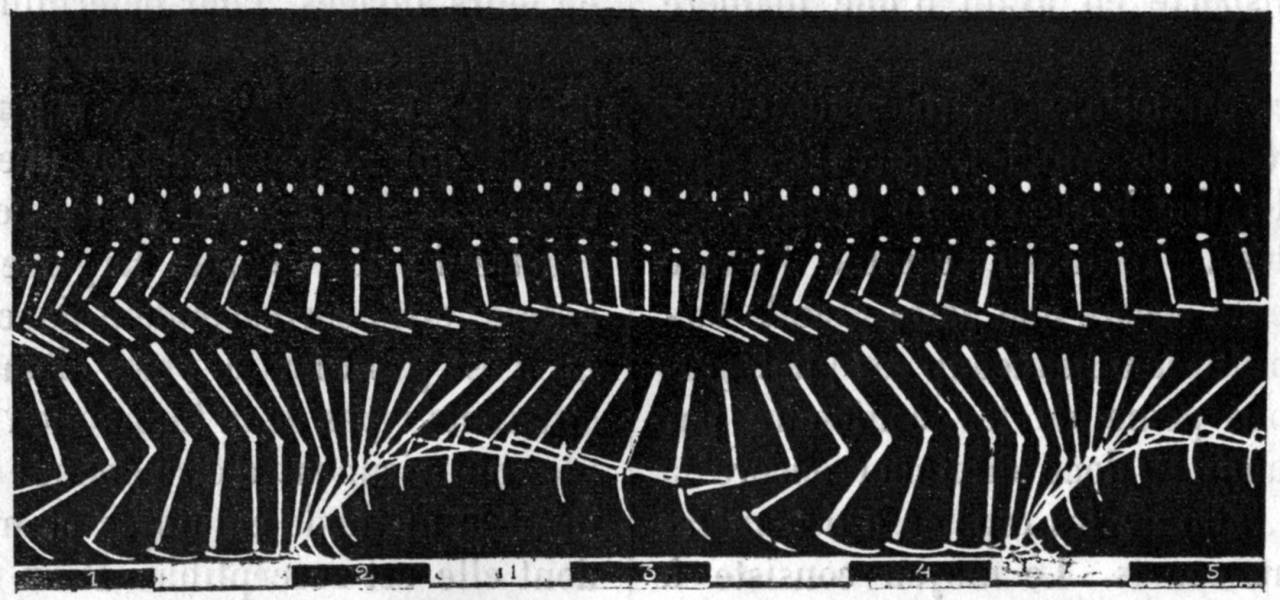

Etienne-Jules Marey, Linear Graph of Running Man in Black with White Stripes, ca. 1882, in “La station physiologique de Paris,” La Nature Via

Marey’s technique for photographing movement over time involved dressing assistants in snug black head-to-toe suits fashioned with reflective tape running down the outside of each limb (fig. 7). When the costumed model walked in front of a black screen during a long exposure, the developed film negative captured only a staggered series of lines, pure abstracted movement. Marey’s studies, like the X-ray, demonstrated how machines can capture images of movements the human eye cannot perceive.

Further reading: Etienne-Jules Marey: A Passion for the Trace.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.