To celebrate the opening of pubs in England’s capital city (at long last) here are some curious tales from three London pubs…

O’Neill’s on Wardour Street

The fashion for faux Irish pubs in Britain had died down somewhat since the heyday of the 1990s but the O’Neill’s chain still has about fifty pubs around the country. None of them have the history of the O’Neill’s at 33-37 Wardour Street and the Flamingo Room they have for hire is a nod to the premises more illustrious past.

It’s not widely known but the Profumo affair, the political scandal that led to the resignation of John Profumo, the Secretary of State for War, in 1963, and ultimately the fall of the Conservative government a year later, was actually all the fault of Georgie Fame. A slight exaggeration maybe, but if he hadn’t employed the Jamaican musician Wilfred ‘Syco’ Gordon to play with his band occasionally, there was a chance that Britain’s political history may have taken a completely different course.

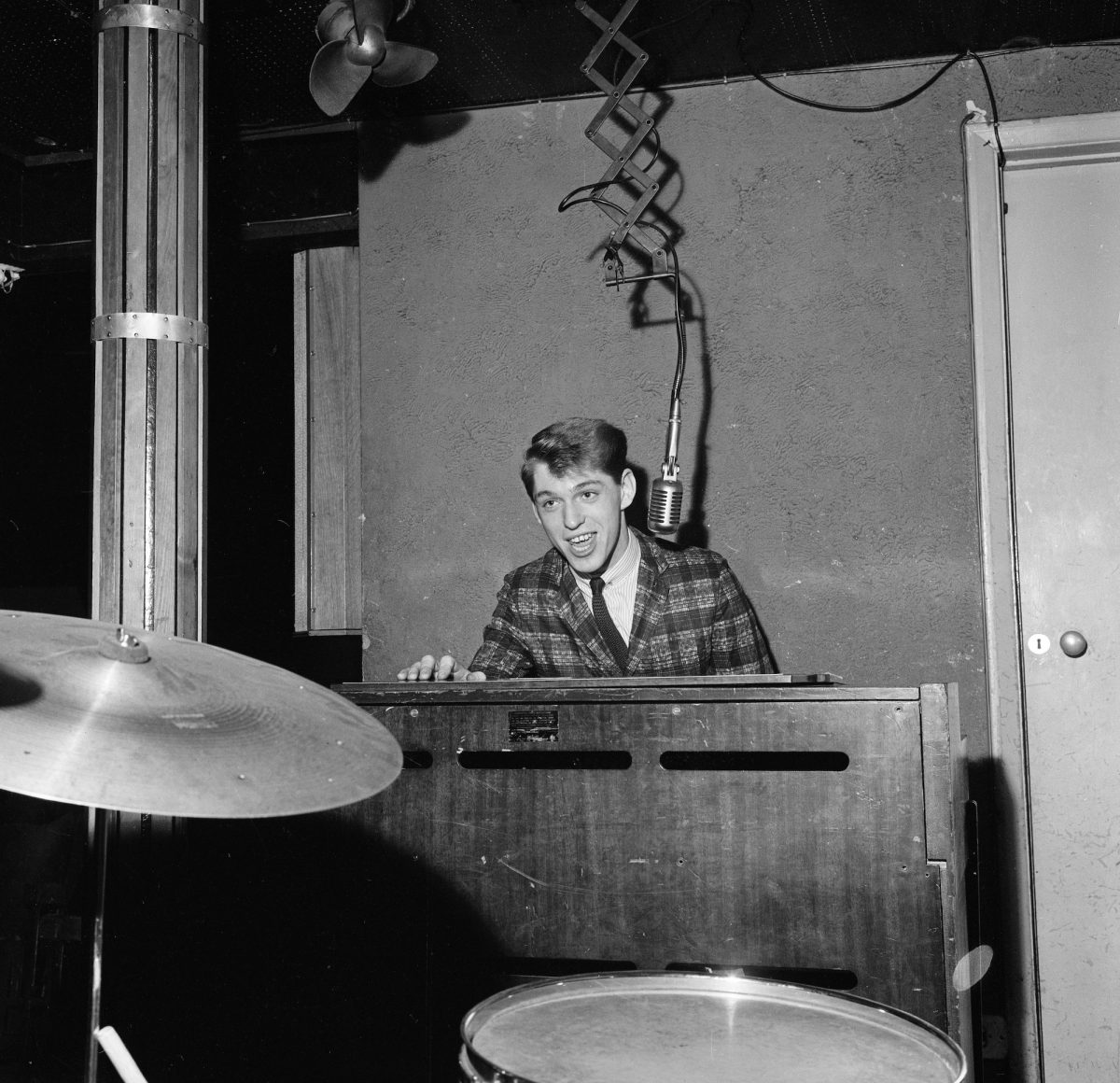

Georgie Fame at the Flamingo Club in 1963

In March 1962, a month after Billy Fury had dismissed them as his backing band – he felt they were ‘too jazzy’ – Georgie Fame and the Blue Flames started a three-year residency at the Flamingo Club. Situated at 33-37 Wardour Street the club was infamous for its pep-pill fuelled weekend all-nighters and stayed open from midnight until six in the morning (the late licence was allowed because it served no alcohol).

Syco often brought to the Flamingo Club his brother Aloysius – known as ‘Lucky’ – a small time drug dealer and occasional blues singer. Lucky was a former lover of Christine Keeler who often went to the All-Nighter club to dance for a few hours after her shift at Murray’s Cabaret Club on Dean Street finished at two. It was at the Flamingo one night where Lucky and another of Keeler’s lovers, the Antiguan Johnny Edgecombe, had a vicious knife fight.

A few weeks later, in a jealous rage after Keeler had said she wanted nothing more to do with him, Edgecombe turned up at Stephen Ward’s Wimpole Mews flat, where Keeler and Mandy Rice-Davies were staying. Getting no answer he started firing bullets through the door and up at the window. Frightened, Christine called Ward at his surgery and he in turn called the police who quickly arrived and arrested Edgecombe.

July 10, 1963 – ”LUCKY” Gordon and John Edgecombe off to meet Lord Denning Who is inquiring into the Profumo Affair

Photo by Frank Monaco / Rex Features ( 9445bt )

Police raid the Flamingo Jazz Club, Wardour Street, London, Britain

Various – 1964

The incident gave Fleet Street, far more deferential to the Establishment those days, a chance to explore the Profumo rumours that had been circulating for months. It was known that Keeler was not only sleeping with Profumo, often at the Wimpole Mews flat, but also the Russian military attaché Yevgeny Ivanov.

The chain of events that started with the fight of Keeler’s jealous ex-lovers at The Flamingo All-Nighter eventually caused John Profumo to resign in disgrace. The Government never really recovered. Harold Macmillan stepped down in October 1963 and after what seemed like endless scandals the Conservatives lost the election to Harold Wilson’s Labour Party a year later.

Georgie Fame once said that his audience at the Flamingo was mostly made up of ‘Black American GIs, West Indians, pimps, prostitutes and gangsters.’ In 1933, Jack Isow’s Shim-Sham Club, based at the very same premises on Wardour Street, attracted, except for the GIs perhaps, a not too dissimilar crowd.

Leonard Feather, later to become the chief jazz critic for the Los Angeles Times, wrote about the Shim Sham (named after a tap dance performed in Harlem in the early thirties) for Melody Maker in 1935. It was headed ‘Another London Harlem Club’ and he wrote: ‘Near-beer, weeds and lounge suits were the order of the night with many. Eight hours for work, eight hours for sleep, and eight hours at the Shim-Sham. That will be the new daily round for these carefree coloured denizens of London.’

The Shim Sham Club was eventually closed down after too many police raids and Jack Isow went on to start Isow’s, a large and sumptuous restaurant on Brewer Street famous for its celebrity clientele. In 1969 Jack Isow married Sheree Winton and became the step-father of fourteen-year-old Dale.

Dale and Sheree Winton in 1959

Far more recently, and 20 years after Georgie Fame began his residency at the Flamingo, a members club opened at 33 Wardour Street called the Wag. Opened by Chris Sullivan, then just 22, it revolutionised clubbing in London, and despite the lack of a VIP area celebrities flocked to the venue. David Bowie even recorded the video for his single Blue Jean there.

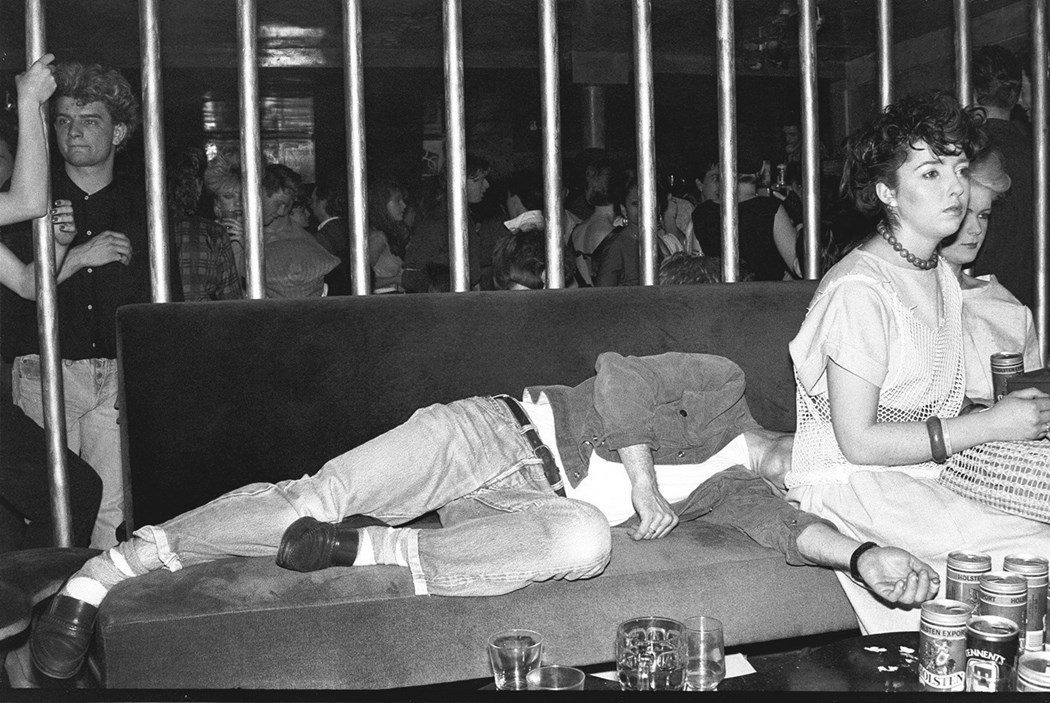

The Wag Club, 1983. – photo by Graham Smith

Sullivan once recalled, ‘At the time, all the West End clubs were playing s*** pop music, so I wanted to open somewhere for me and people like me, a cool club with a great mix of music, whether it be jazz or funk or disco or reggae, a different vibe every night.’ At one point even Georgie Fame came back to play. He was shocked when he walked out and a crowd of immaculately dressed mods looked just as they had back in his early sixties heyday.

Almost exactly 20 years after it first opened the Wag closed down in 2001. Not long after the building became the largest of the O’Neill’s ‘Irish’ pub chain. It’s still there and it has a space to hire called the Flamingo Room – a nod to the premises more illustrious past.

The Blind Beggar

Scene outside the Blind Beggar pub on Whitechapel Road, Stepney, where Richardson gang associate George Cornell was shot in March 1966. Ronald Kray was charged with his murder. The car parked outside belongs to Mr Cornell. 11th March 1966.

One hundred and one years after the evangelist William Booth preached his first open-air sermon outside the Blind Beggar Public House on the Whitechapel Road – a sermon which ultimately led to the establishment of the Salvation Army – Ronald Kray walked into the very same pub. It was 8.30pm on 9 March 1966 and Kray was accompanied by his right-hand man, Ian Barrie, while the driver, John ‘Scotch Jack’ Dickson, was told to wait outside in his Mark 1 Cortina.

A pub had been on the same spot in Whitechapel since 1673 and Ronald Kray wouldn’t have been the first villain, big-time or otherwise, who had found himself in that infamous East End establishment. Before the First World War, the Blind Beggar was the meeting-place of a gang of pickpockets and ne’er do wells. One of them called ‘Bulldog’ Wallis got into a fight with a Jewish couple and ended up killing the man by pushing the tip of his umbrella through one of his eyes. Wallis was arrested but after no witnesses could be found he was released from police custody through lack of evidence. He returned to the Blind Beggar a hero, and was accompanied by his cheering supporters.

There was no cheering when Ronnie Kray arrived that evening in 1966. He and Barrie entered the pub quietly and without a fuss. Kray had been told that George Cornell, a member of the sadistic and ruthless south London Richardsons’ gang, was drinking there. Cornell was particularly disliked by Ronnie, who would later write: ‘In front of a table full of villains, George Cornell called me a “fat poof”. He virtually signed his own death warrant.’

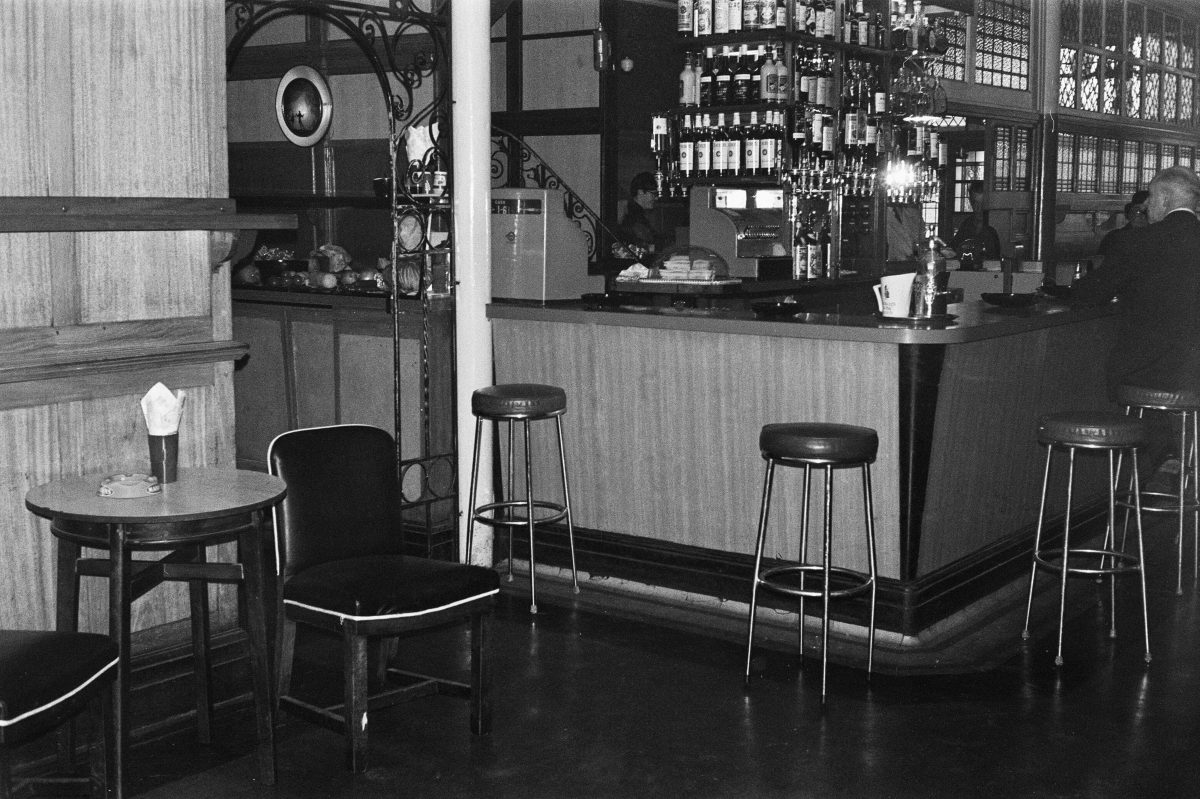

Inside the Blind Beggar pub on Whitechapel Road, Stepney, whereRichardson gang associate George Cornell was shot. The stool near the cash register is where Mr Cornell was shot. Ronald Kray was charged with his murder. 11th March 1966.

A police photograph showing blood stains on the floor inside the Blind Beggar public house in Whitechapel where George Cornell was killed. Ronald Kray and John Barrie were convicted of the murderand sentanced to life. * and Reginald Kray was convicted of accessory after the fact and sentenced to 10 years imprisonment. The photo is one of many documents and files that have become public at the Public Records Office in Kew in south west London.

George Cornell put down his light ale when he saw Ronnie approaching and said, sarcastically, ‘Well, look who’s here … ‘. Without a word Ronnie walked over to Cornell, took out a 9mm Mauser from his pocket and shot him through his head at close range.

The police found it impossible to find witnesses to the murder. The barmaid at the Blind Beggar said she hadn’t seen anything and nor had an old man who had been drinking at the bar. They asked him why he wouldn’t help put Ronnie Kray away: ‘I hate the sight of blood,’ he said, ‘particularly my own.’

It was to be over two years before the Kray Twins were arrested for two murders including George Cornell. The Twin’s accountant, Leslie Payne, began talking to the police and the code of silence that had protected the twins for so long began to be broken down.

On the evening of Tuesday 4 March 1969 and after six hours 55 minutes of deliberation, a jury unanimously found Ronnie and Reggie Kray guilty of murder. Mr Justice Melford sentenced the twins to 30 years with no chance of parole. For years Krays’ supporters, of which there were many, maintained that only other villains and members of the East End underworld suffered during their ‘reign’. For the ordinary person, the East End was safer back then they’d say. When the broadcaster, photographer and writer Dan Farson once told the Cockney actor Arthur Mullard that the Krays ‘only killed their own kind’, Mullard responded, ‘Yus, ‘uman bein’s!’

FACES AT THE WINDOW OF A BLACK MARIA AS IT HEADS TOWARDS BRIXTON PRISON AFTER THE CONCLUSION OF PROCEEDINGS AT THE OLD BAILEY TRIAL OF THE KRAY TWINS AND OTHERS. THE JURY RETURNED THEIR VERDICT AFTER A RETIREMENT OF 6 HRS AND 55 MINS. 4th March 1969

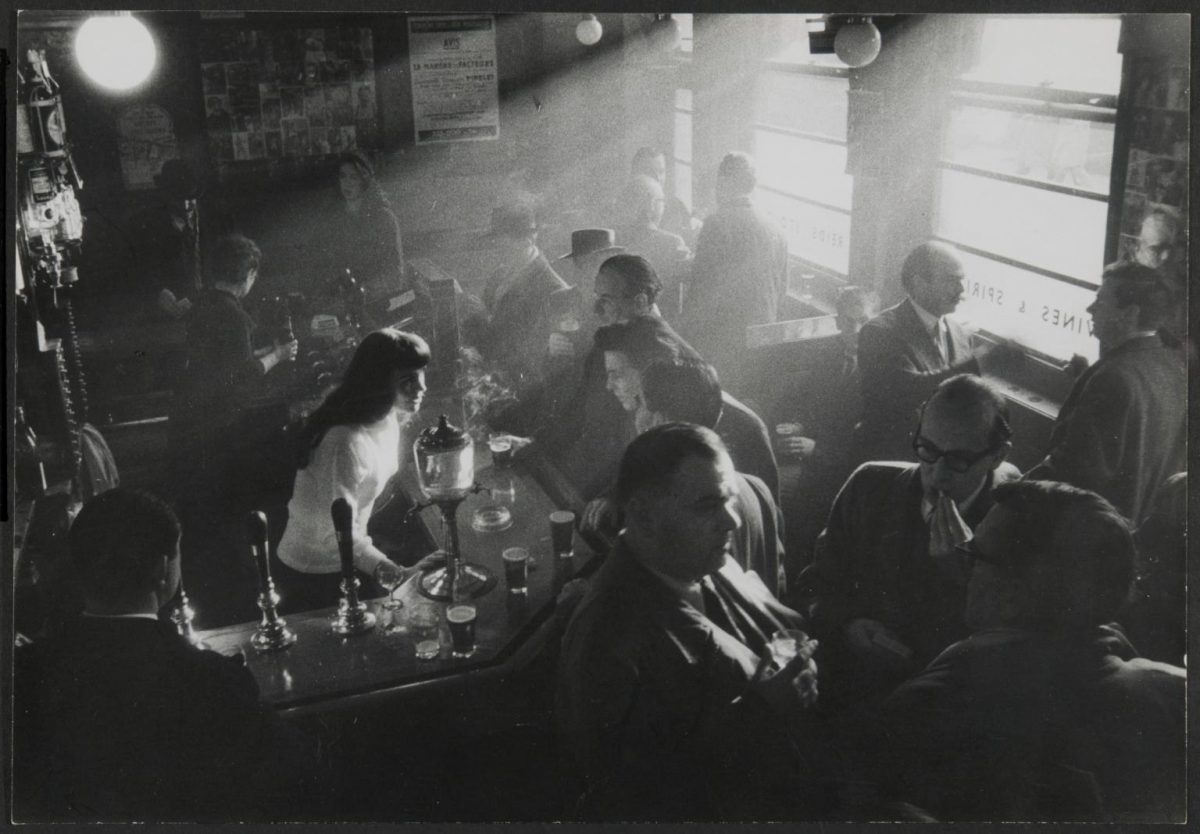

Gaston Berlemont’s pub, The French House, Soho, London 1955 Willy Ronis

The French House

Soho ‘may not be what it was’ wrote Picture Post magazine in 1942 (it seems people have always said this and probably always will) before describing the area as ‘honeycombed with cosmopolitan joints, dives and dumps’. However, it wrote, the centre and pivot of Soho is the most conventional looking English pub with a most conventional name – the York Minster.

It may have looked and sounded English but during the war it’s clientele were almost all French most of whom drank not beer but the sweet aromatic aperitifs of ‘the continent’ – Cinzano, Ricard, Cap Corse, Dubonnet and Pernod.

Although Picture Post described the York Minster’s wartime customers as mostly from the ‘lower French ranks’ (officers much preferred L’Escargot, the Coquille and Chez Victor), Charles de Gaulle is said to have drawn up his Free French call to arms at the pub. This is almost certainly not true, although the General at one point did drop by to have a patriotic glass of wine. The words ‘A tous les Français: La France a perdu une Bataille, elle n’a pas perdu la guerre’, however, were soon displayed on de Gaulle posters in all the French restaurants around Soho. This despite a rumour that, privately, many of the proprietors supported the Vichy government.

Free French sailors and customers at the York Minster pub in Soho, London, in 1941. (Kurt Hutton)

York Minster Victor Berlemont favourite haunt variety artists, prize fighters and racy mixture of English Pub and French Cafe 1939

The York Minster had originally opened as the Wine House by a German national called Schmidt. When he was deported and sent to the Isle of Man at the start of the First World War he was replaced by a Belgian man called Victor Berlemont. Berlemont changed the name to something suitably patriotic and became famous for throwing out troublesome drunks by shouting, ‘I’m afraid one of us will have to leave, and it’s not going to be me!’. Victor was succeeded by his son Gaston Berlemont who was born in London the year his father took over the pub.

After the war artists and writers made the Soho pub their own including Francis Bacon, Lucien Freud, Brendan Behan (who would hungrily eat his Bouef Bourginon with both hands) and Dylan Thomas. It’s often written that after a particularly good lunch Thomas left his original copy of Under Milk Wood under a table at the York Minster. He told the producer Douglas Cleverdon, who had taken seven years to coax the work out of the Welsh writer, that if he found the manuscript he could keep it. This he did, but not at the York Minster, as legend has it, but at the Swiss Tavern (now Compton’s) around the corner in Old Compton Street.

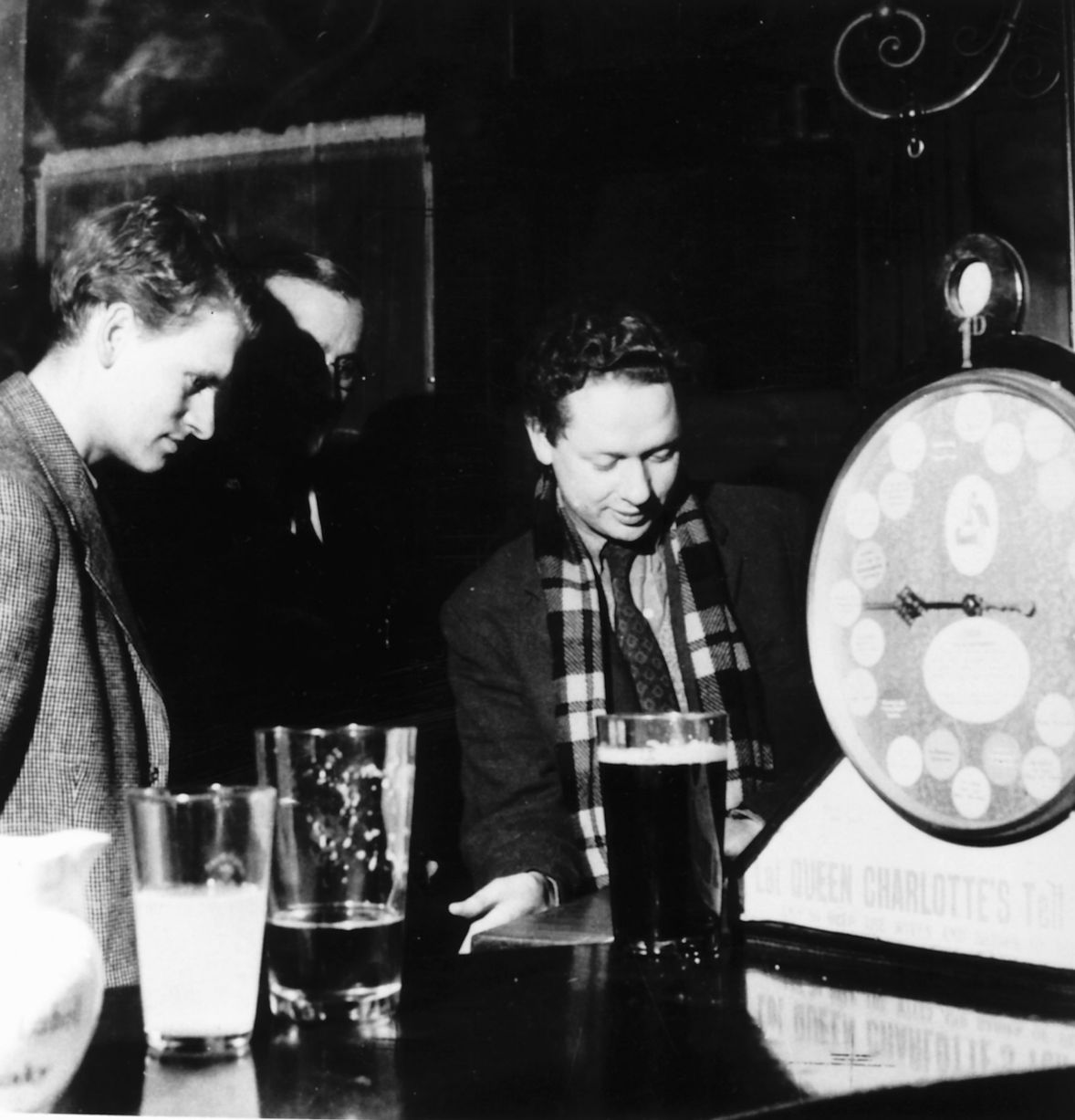

Dylan Thomas in the pub

After the fire at the real York Minster in 1984 donations intended for York started arriving at the pub. After returning the money Berlemont found that the clergymen had also been receiving unsolicited crates of claret meant for the pub. To avoid any future confusion the York Minster at 49 Dean Street, always known as the ‘French’, was formally renamed as The French House. Beer, never a priority, is still only sold in half-pints and apparently more Ricard is sold than anywhere else in Britain. Or is that another tall story.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.