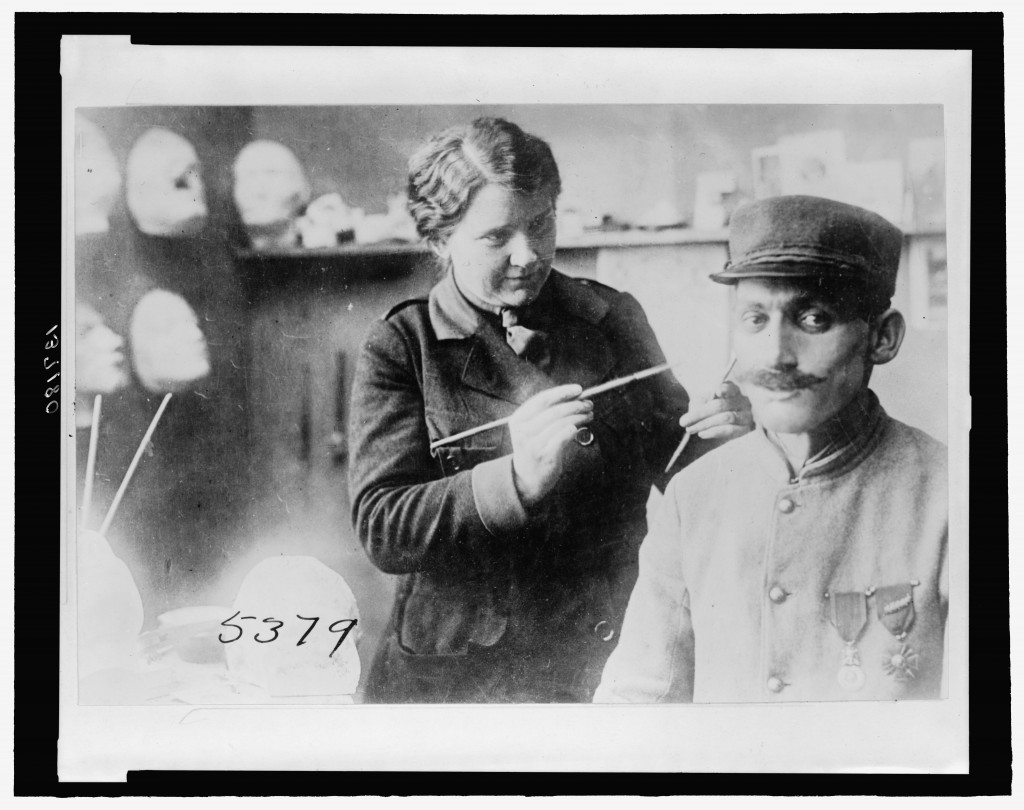

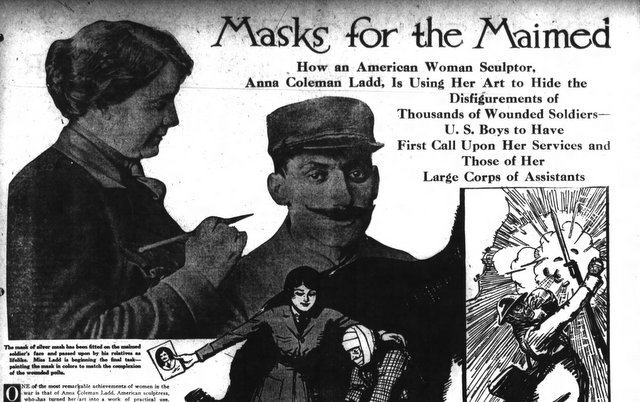

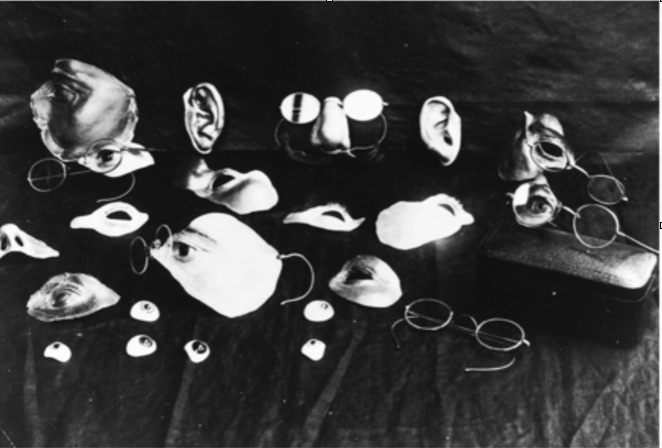

Anna Coleman Ladd (1878–1939), an American sculptor, ran the Studio for Portrait Masks in Paris. There soldiers disfigured in the First World War were given new faces fashioned from galvanized copper one thirty-second of an inch thick, weighing between four and nine ounces and often held in place by spectacles. Once in place, Ladd used enamel paint to create skin tones. By the time Ladd retuned to the US, she’d created 189 masks.

There was no way of maintaining them. As she wrote of one early patient: “He had worn his mask constantly and was still wearing it in spite of the fact that it was very battered and looked awful.”

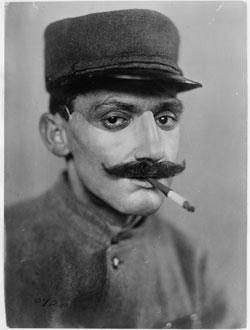

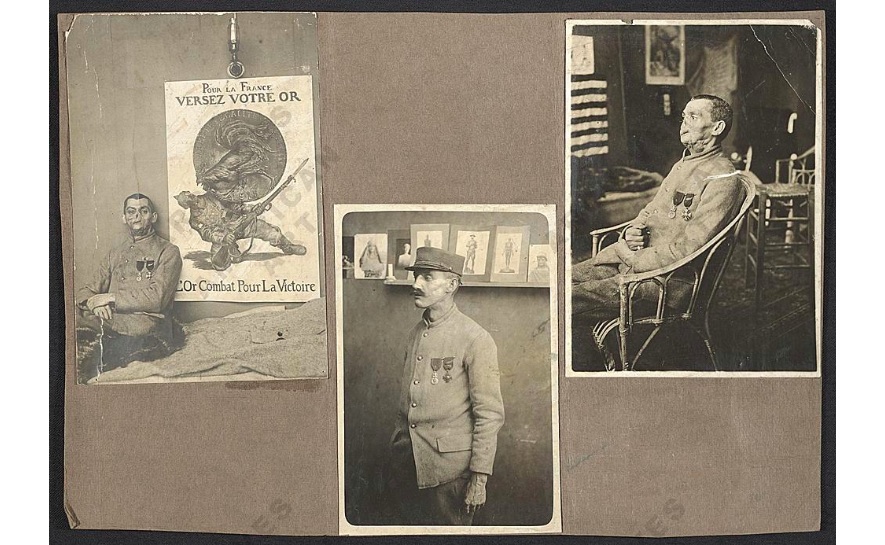

Documentation of a World War I soldier’s facial reconstruction, ca. 1918. Via

The patients who arrived at the clinic, which was supported by the American Red Cross, had suffered terribly. “He lay with his profile to me,” wrote Enid Bagnold, a volunteer nurse (who’d achieve success as the author of National Velvet). “Only he has no profile, as we know a man’s. Like an ape, he has only his bumpy forehead and his protruding lips—the nose, the left eye, gone.”

In A Surgeon’s Fight to Rebuild Men, Dr. Fred Albee, an American surgeon working in France, explained why facial injuries were so common. ‘They seemed to think they could pop their heads up over a trench and move quickly enough to dodge the hail of machine-gun bullets,” he wrote. “…The psychological effect on a man who must go through life, an object of horror to himself as well as to others, is beyond description… It is a fairly common experience for the maladjusted person to feel like a stranger to his world. It must be unmitigated hell to feel like a stranger to yourself.”

In Ward Muir’s The Happy Hospital (1918), the author, a corporal in the Royal Army Medical Corps (RAMC), adds:

“Hideous is the only word for these smashed faces: the socket with some twisted, moist slit, with a lash or two adhering feebly, which is all that is traceable of the forfeited eye; the skewed mouth which sometimes—in spite of brilliant dentistry contrivances—results from the loss of a segment of jaw; and worse, far the worst, the incredibly brutalising effects which are the consequence of wounds in the nose, and which reach a climax of mournful grotesquerie when the nose is missing altogether.”

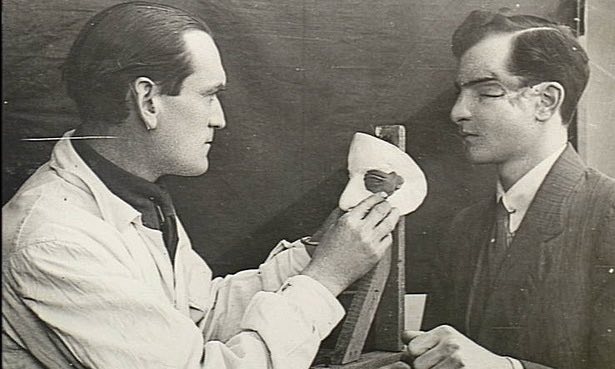

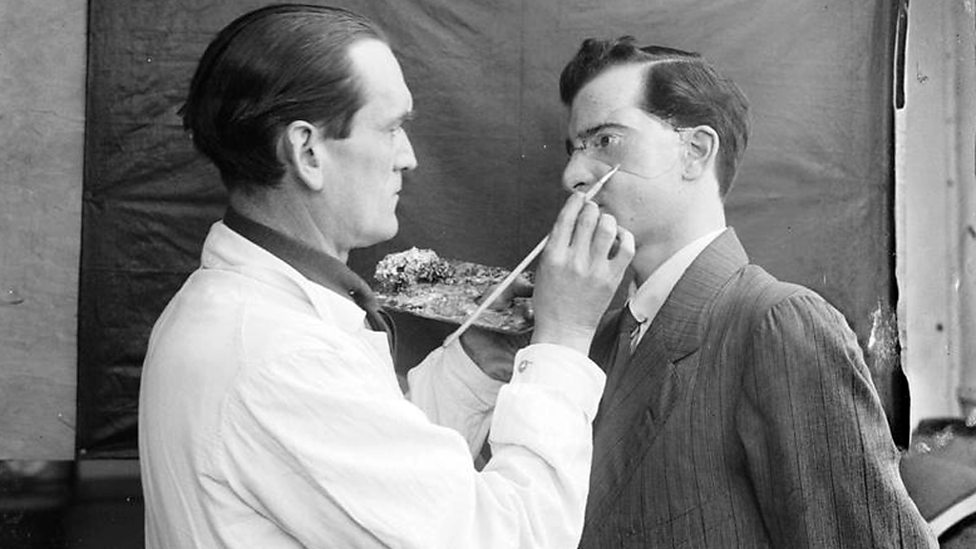

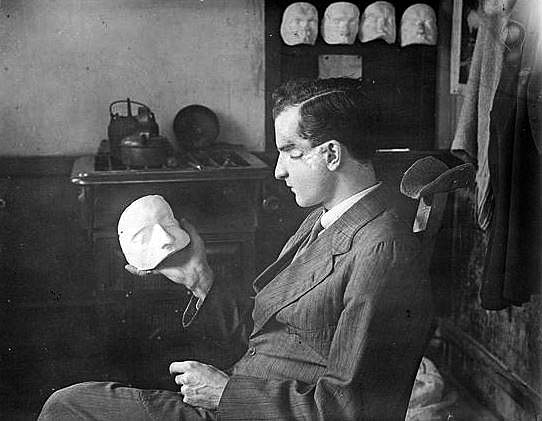

Aiding Ladd’s work in anaplastology was British sculptor Francis Derwent Wood (1871-1926). He founded the Masks for Facial Disfigurement Department at the Third London General Hospital in Wandsworth (aka ‘The Tin Noses Shop’) and ‘was a pioneer in the use of metal masks, both lightweight and more durable than the then commonly used rubber masks’.

Wood wrote in The Lancet medial journal:

“I endeavour by means of the skill I happen to possess as a sculptor to make a man’s face as near as possible to what it looked like before he was wounded. My cases are generally extreme cases that plastic surgery has, perforce, had to abandon; but, as in plastic surgery, the psychological effect is the same. The patient acquires his old self-respect, self assurance, self-reliance,…takes once more to a pride in his personal appearance. His presence is no longer a source of melancholy to himself nor of sadness to his relatives and friends.”

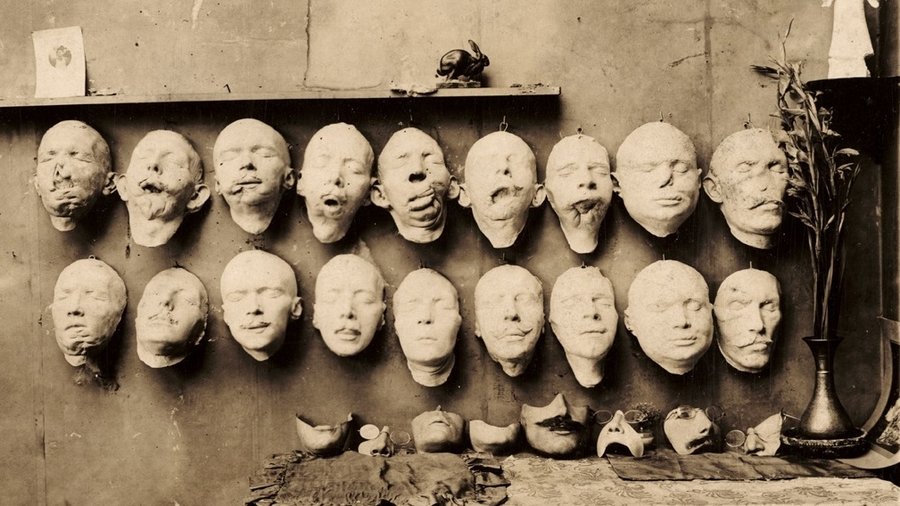

That so few images of the masks exit is odd. Were they airbrushed from history and public record? “I never [before] felt any embarrassment… confronting a patient,” notes Wood, “however deplorable his state, however humiliating his dependence on my services, until I came in contact with certain wounds of the face.”

As Suzannah Biernoff writes: “Unlike amputees, these men were never officially celebrated as wounded heroes. The wounded face, as Sander Gilman intimates, is not equivalent to the wounded body; it presents the trauma of mechanised warfare as a loss of identity and humanity.”

Below is a film of Ladd working at the Studio for Portrait Masks. It also feature Derwent. Zoe Beloff tells us part of what we see:

The film shows Ladd dipping a sculpted ear into a chemical solution and adjusts the current. The ear, plated with copper, will then be attached to a soldier. To make the attachment, a cast was made of his disfigured features (after his wounds had healed), a suffocating ordeal. The sculptor used the cast to re-create the man’s missing parts and prewar appearance. Details such as eyebrows or moustaches were made from real hair or slivers of tinfoil and glued on. It was difficult to paint masks to convincingly resemble flesh, despite the skill that went into their creation…

After the war people stopped paying attention. The war wounded became just another part of the human landscape. The last image in Plastic Reconstruction is of a soldier who literally takes off his face. He turns directly to the camera, fixes us with his one good eye, and the film abruptly ends. We are left with an indelible afterimage: a “faceless” man.

Via: Smithsonian, PublicdomainReview, Oxford Accademic

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.