Scheid, of Dunkirk, fired three times at his wife. Since he

missed every shot, he decided to aim at his mother-in-law,

and connected.

Félix Fénéon (1861-1944) understood the power of a ‘tweet’ in early 20th-century France. Between May and November 1906, Fénéon’s three-line reports appeared in Paris newspaper Le Matin. His faits divers column – known in journalistic arenas as chiens écrasés (‘run-over dogs’; or by the rough English equivalent ‘drop the dead donkey’) – was delivered with no byline. “I aspire only to silence,” said the elusive Fénéon.

His pithy notes dealt with anything and everything, from deaths, hoaxes, sex, and crime to affairs of State, scandal, the election of May queens, the theft of phone wires and pretty much anything that ever happened to French Navy boats.

In all, Fénéon wrote 1220 of his short stories in three lines. And they’d have been forgotten had his lover Camille Plateel not pasted them into a scrapbook. Jean Paulhan liked what the saw and published the writer’s work as a collection.

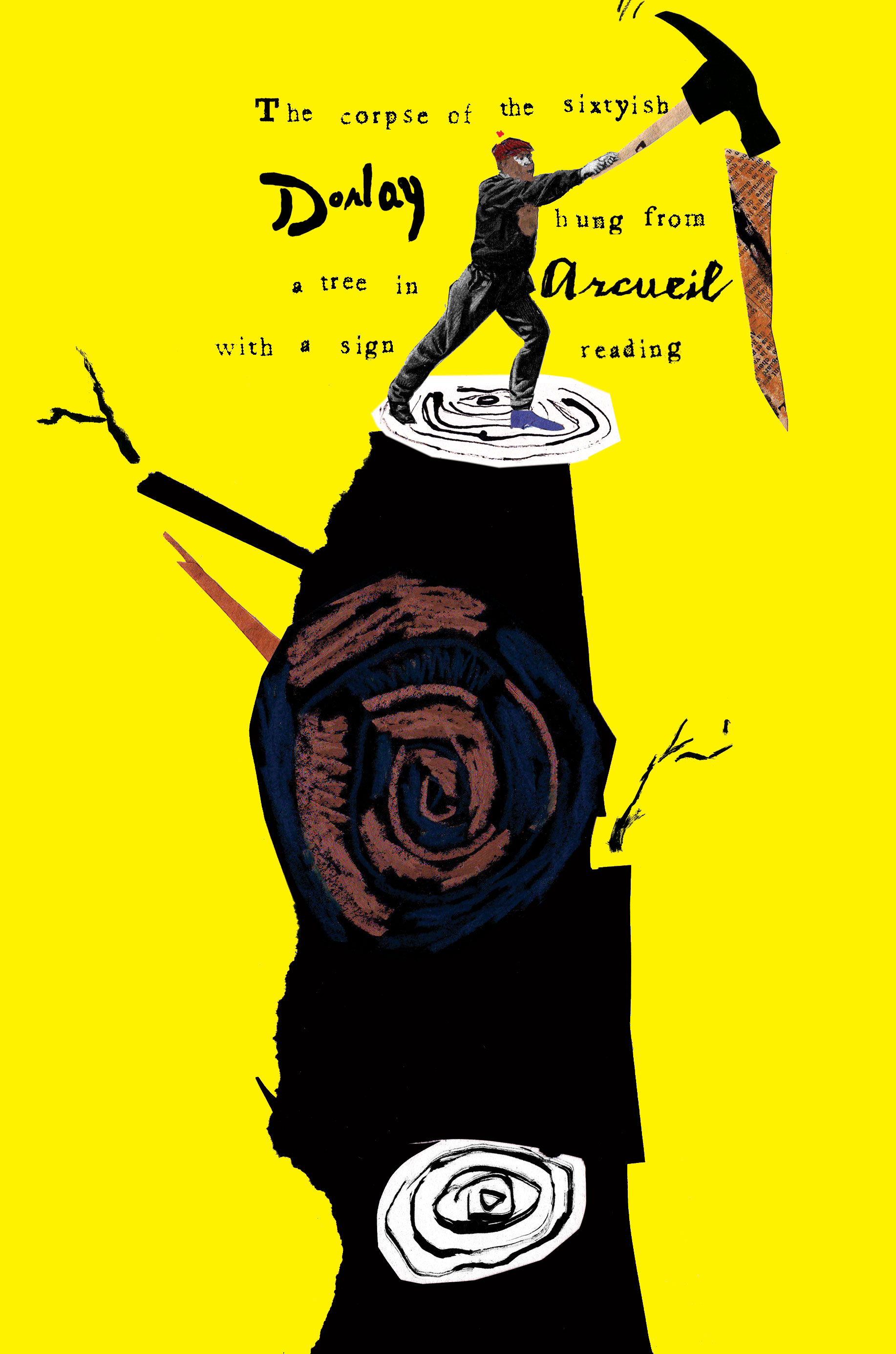

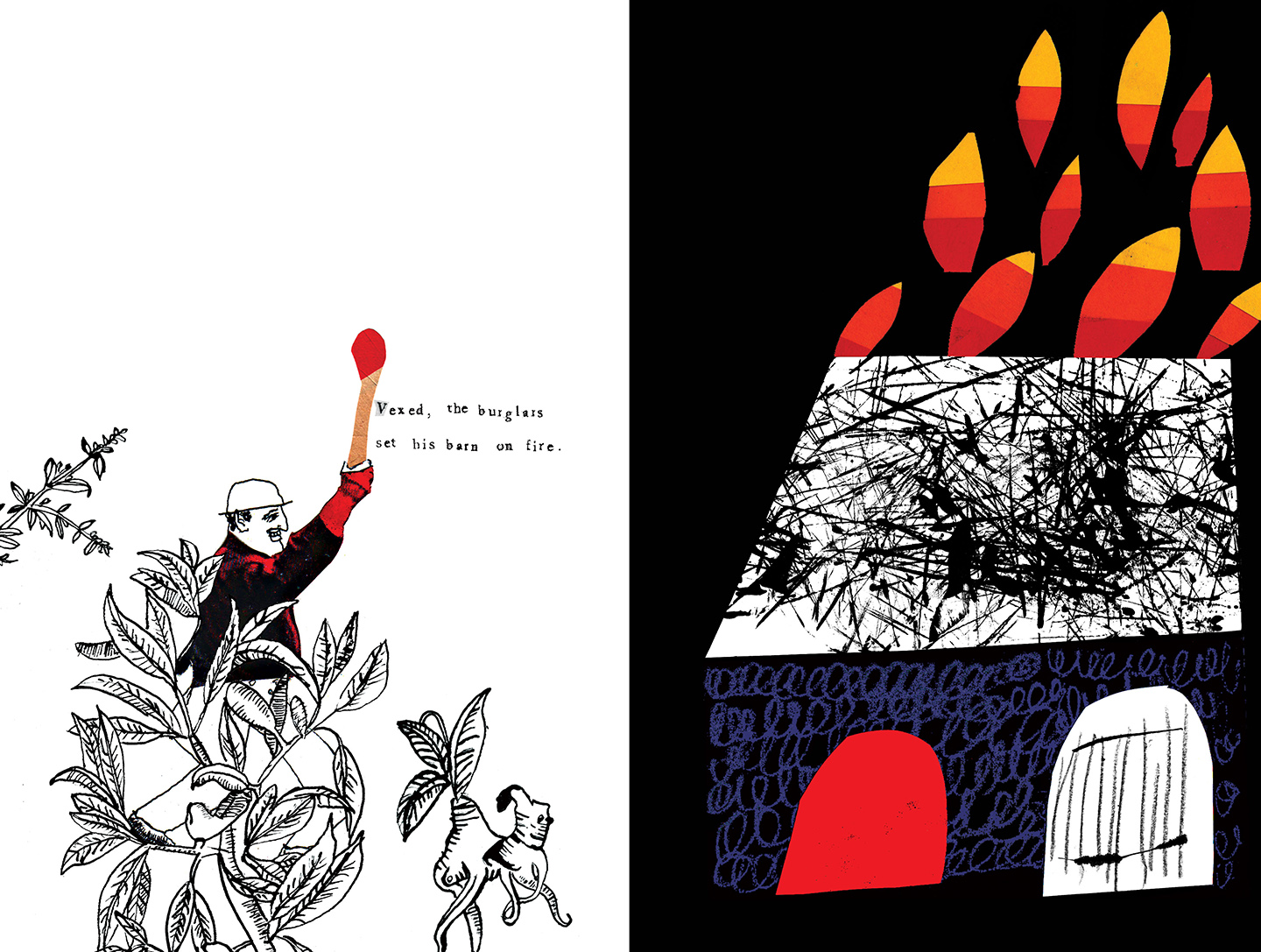

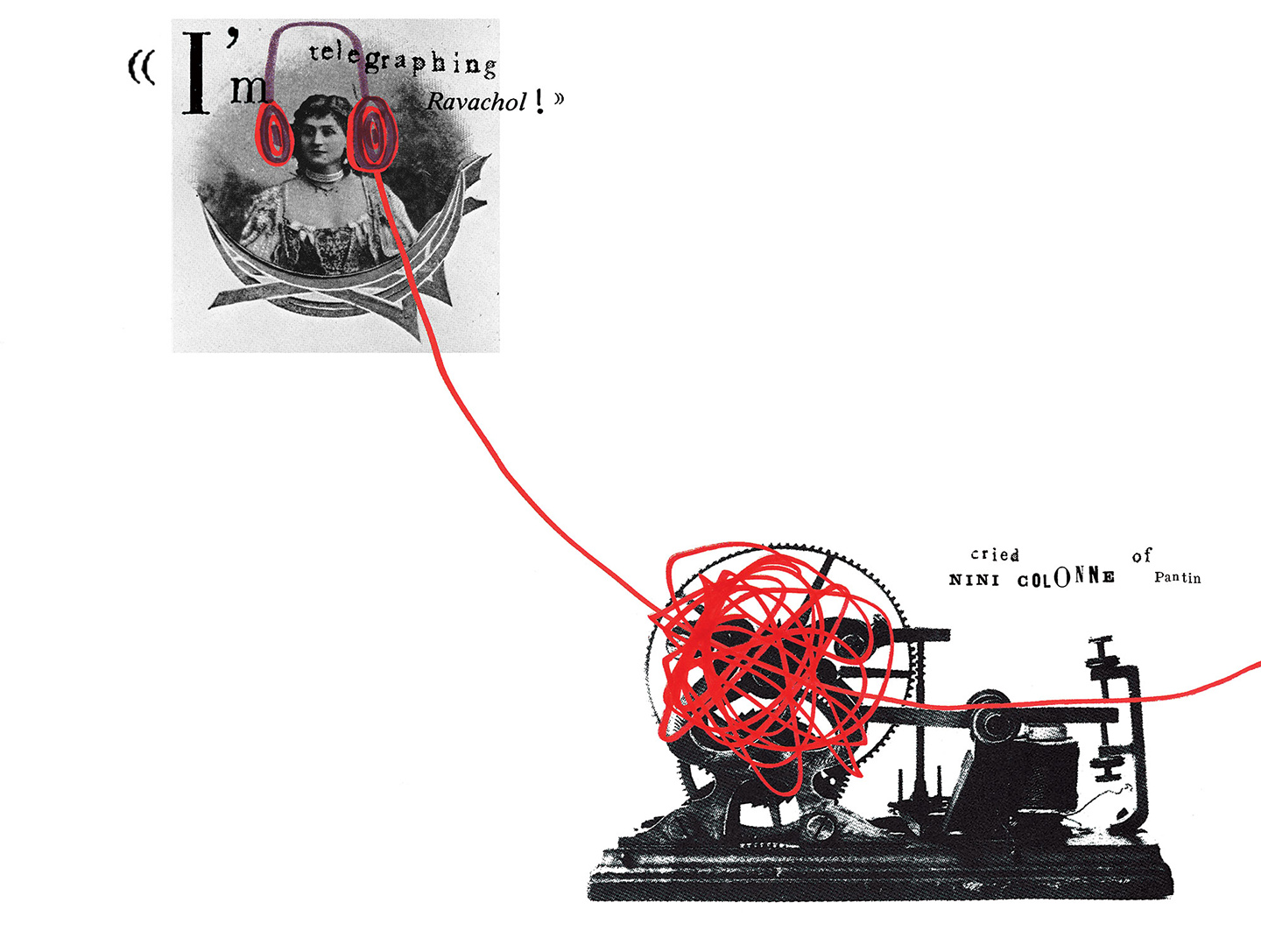

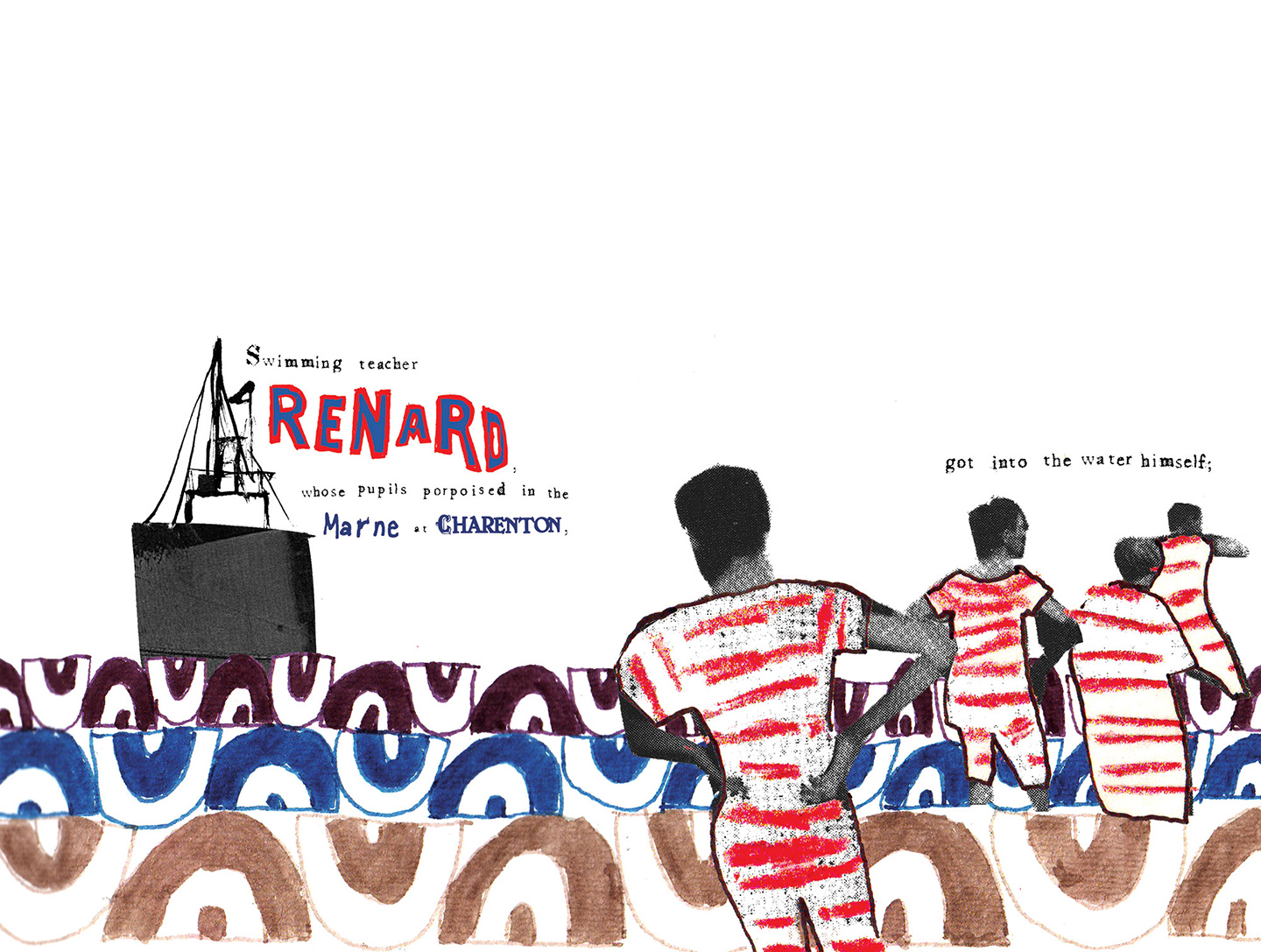

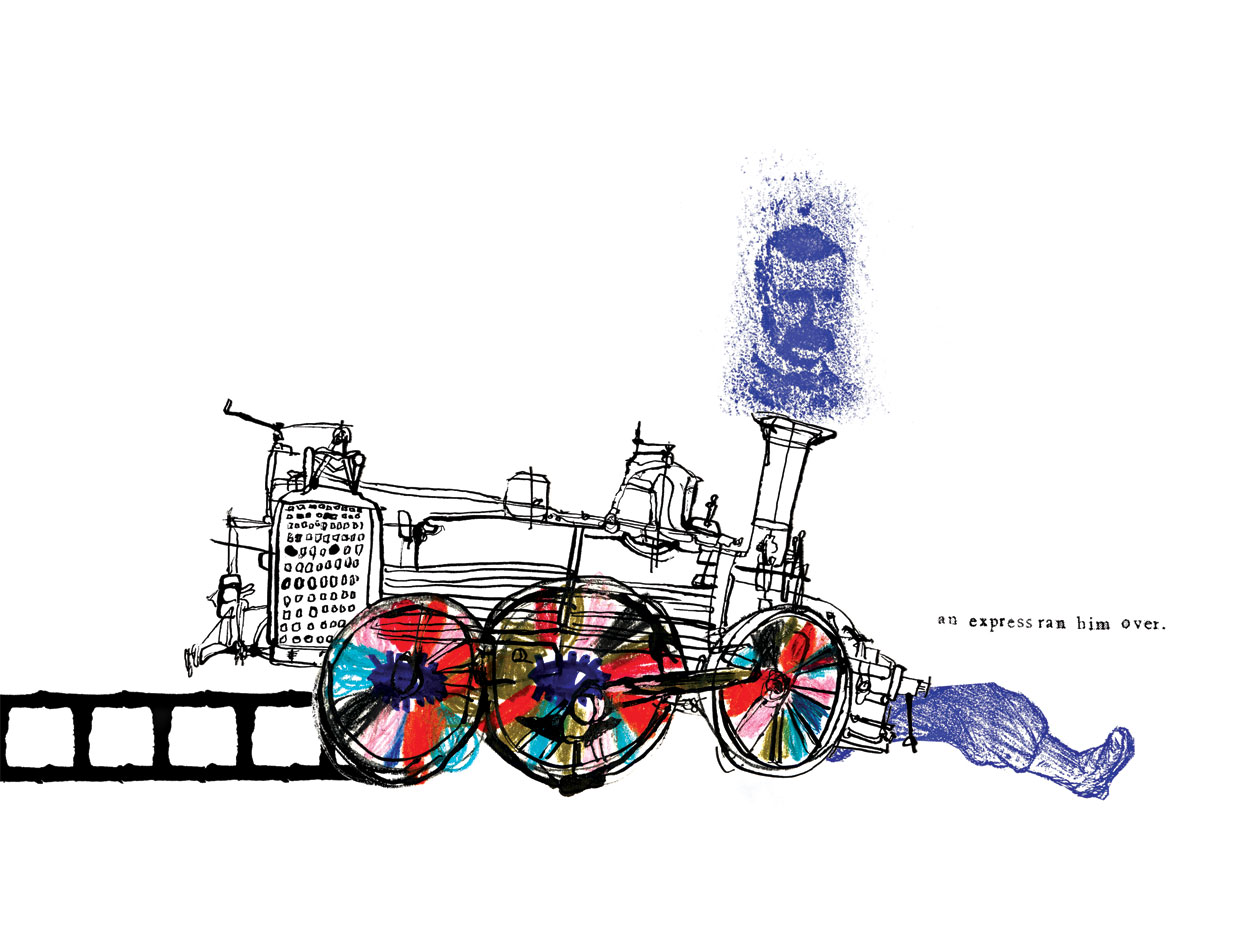

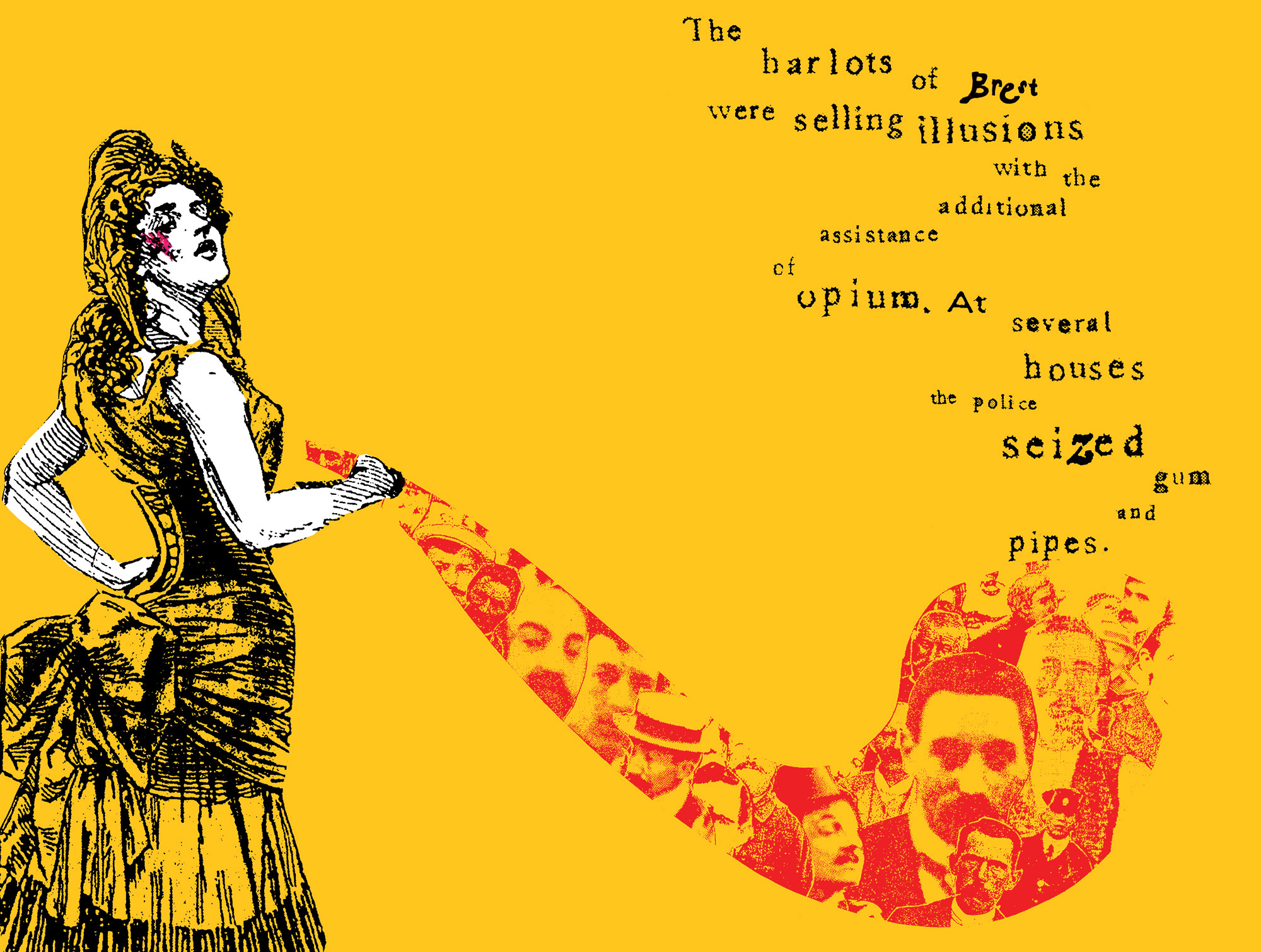

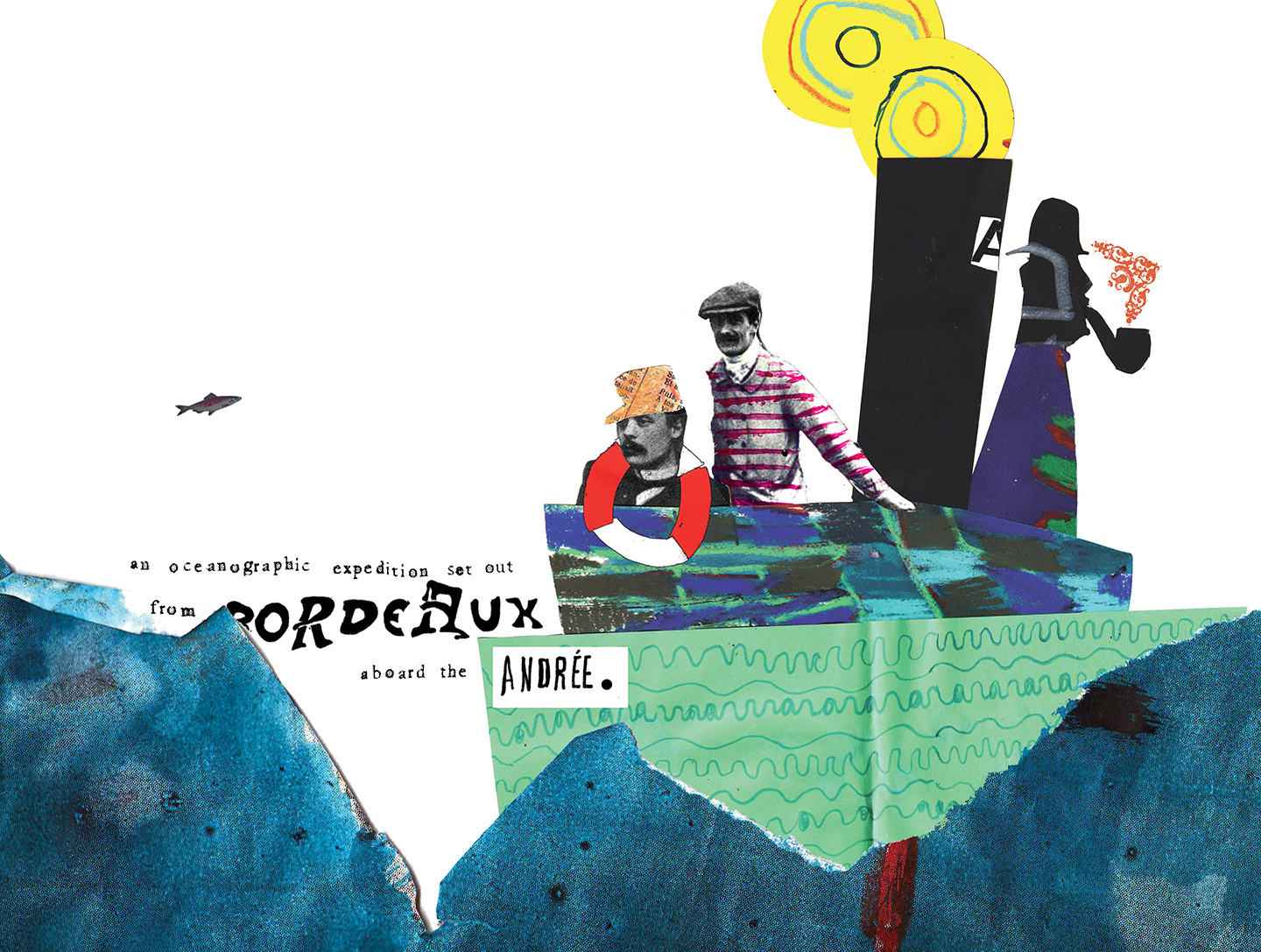

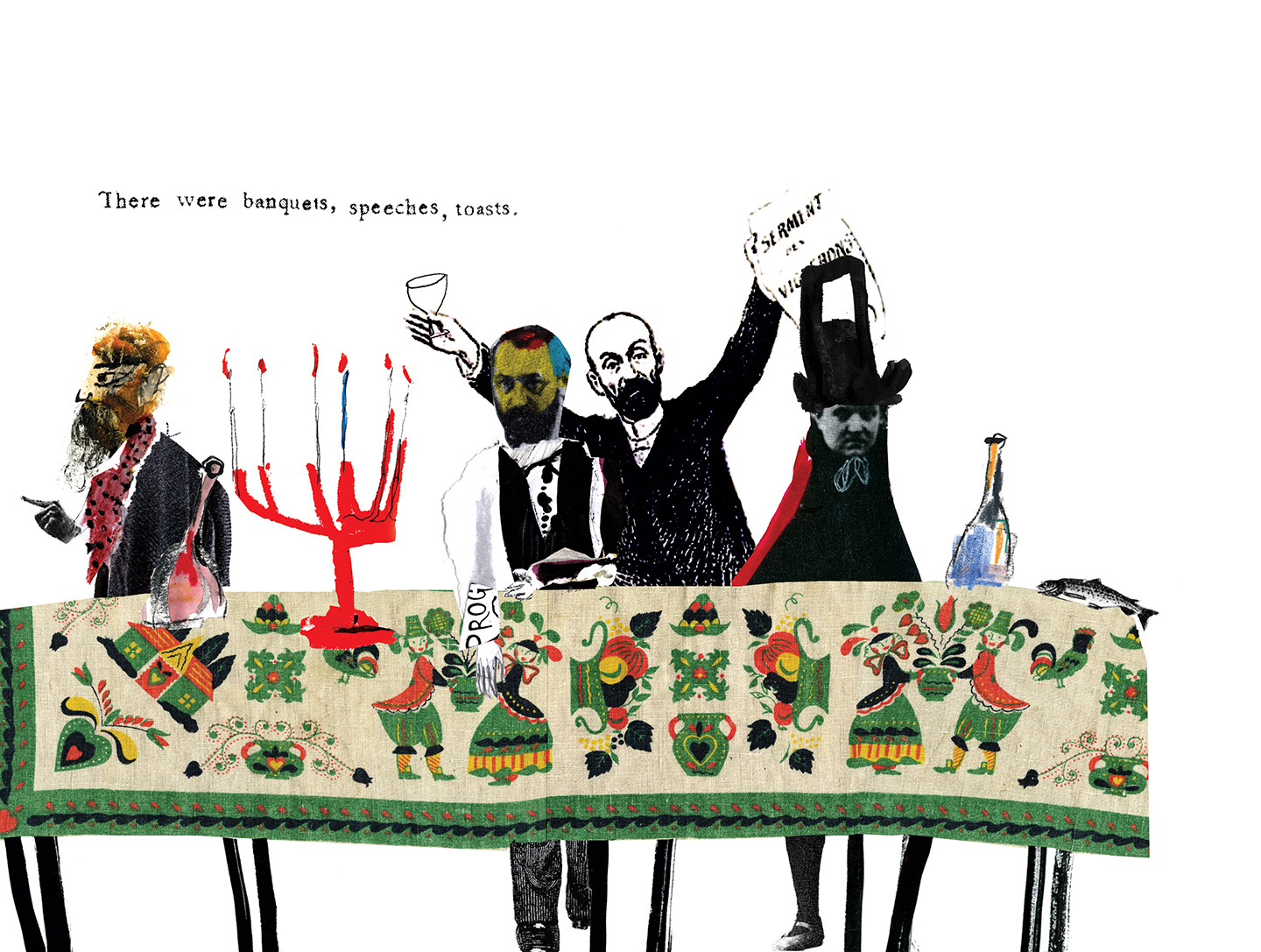

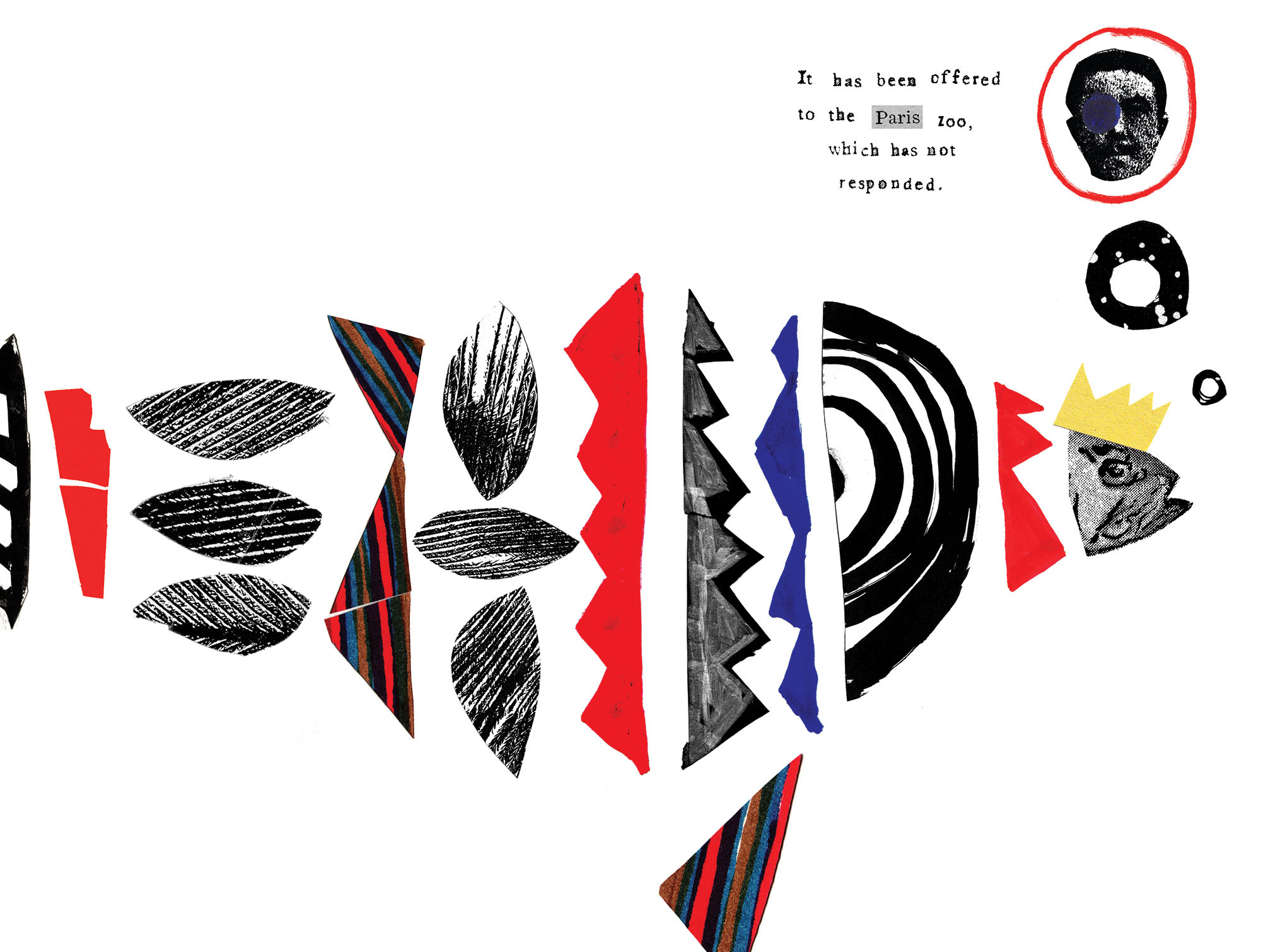

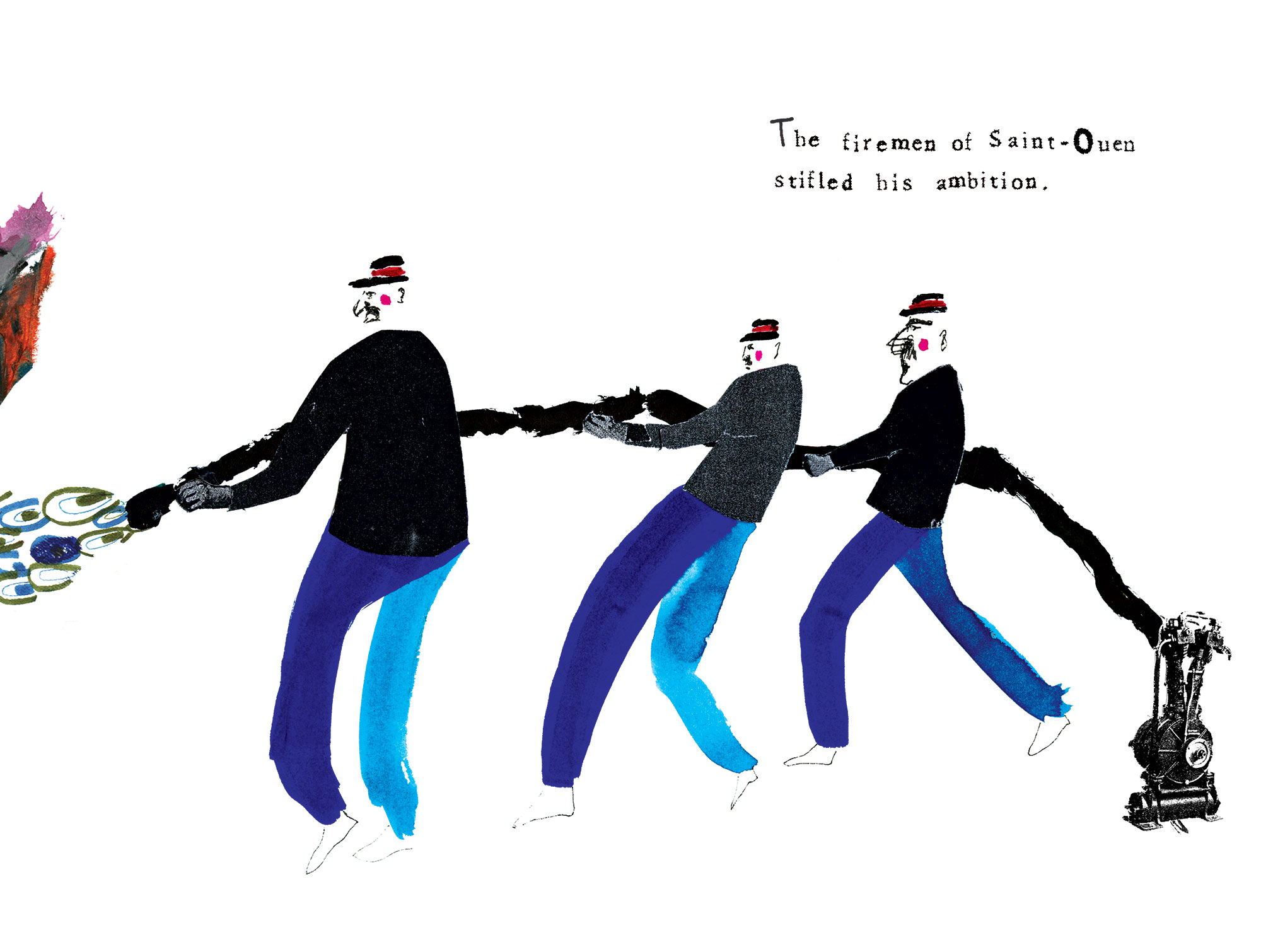

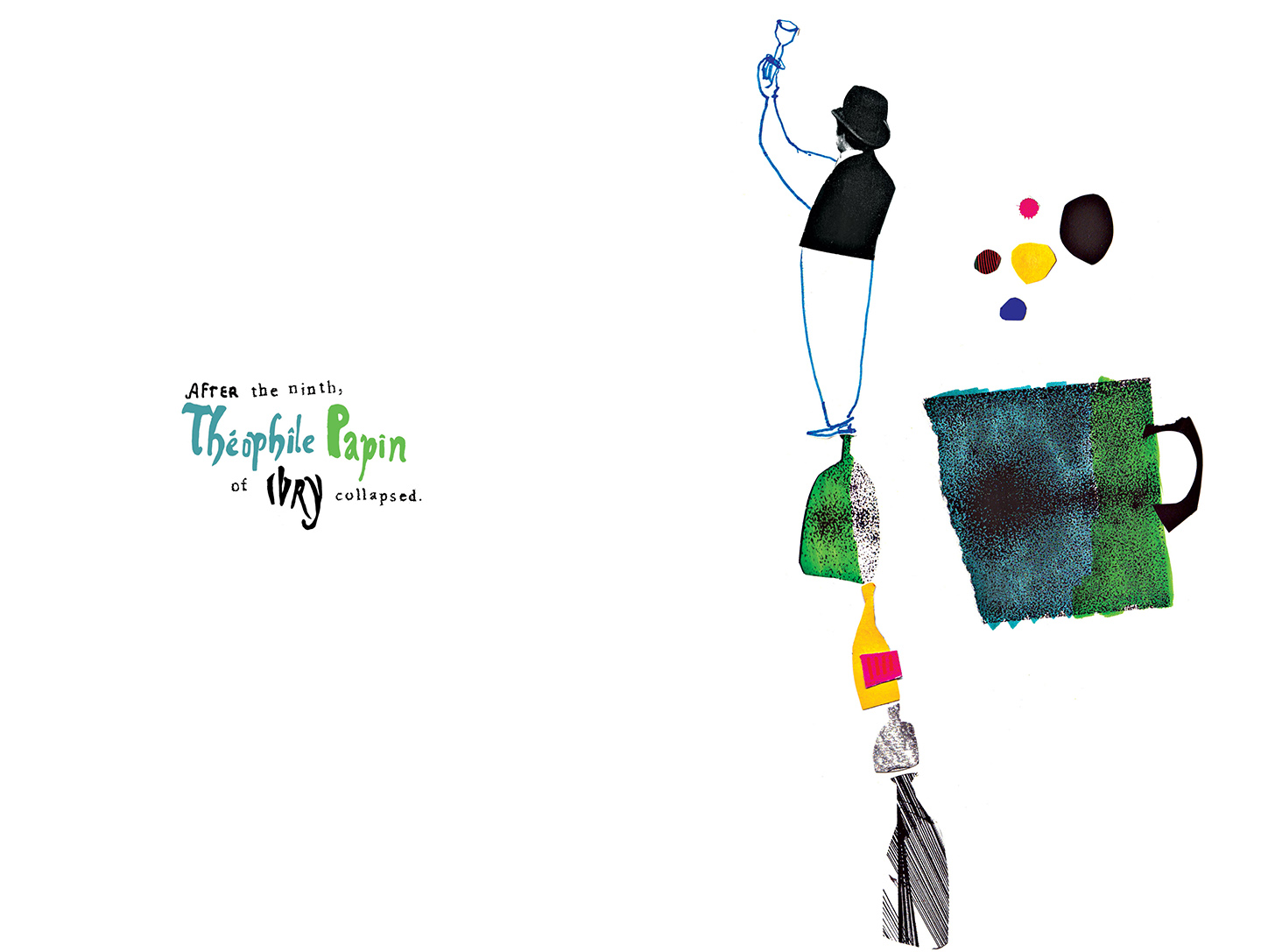

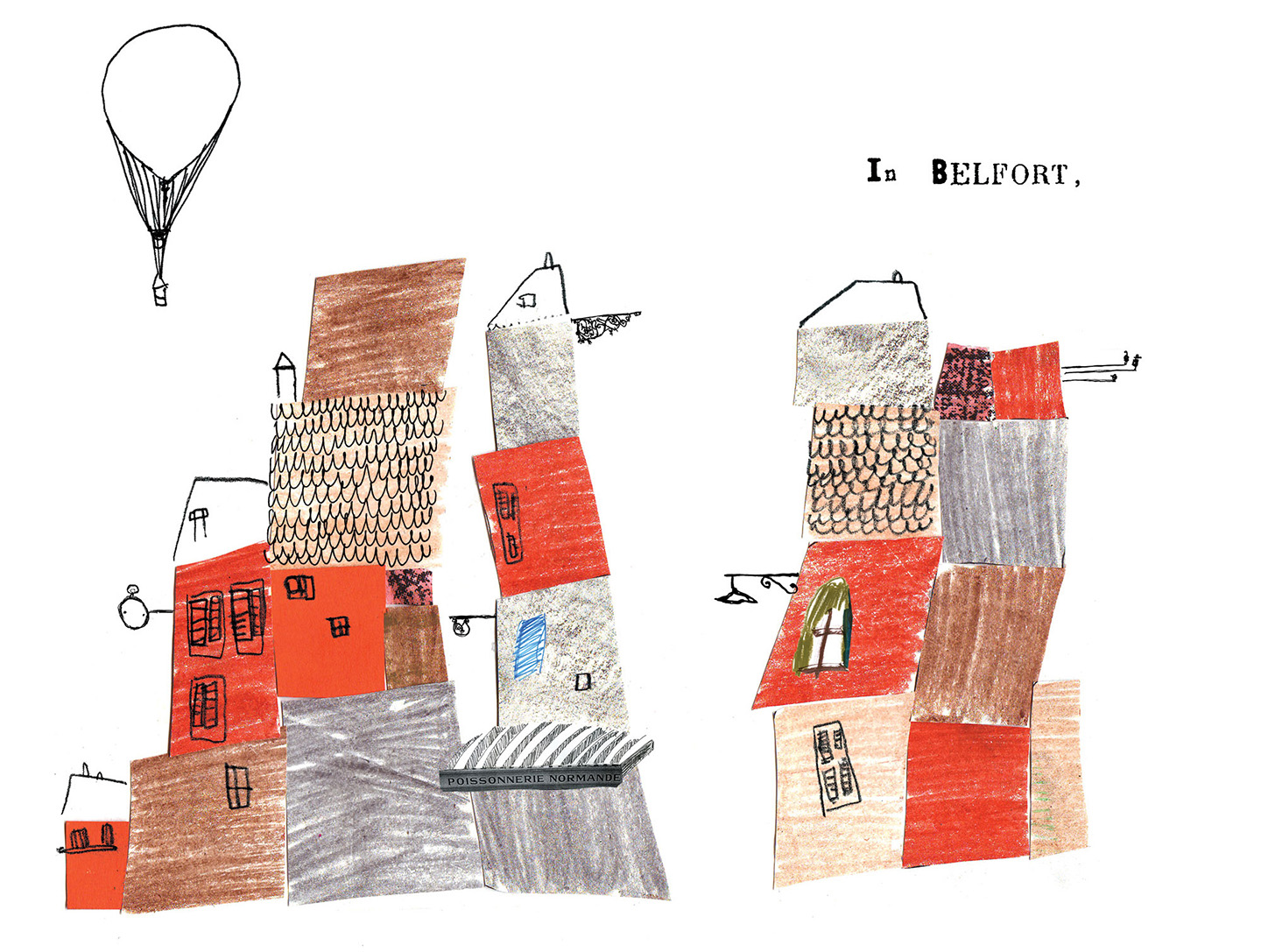

In Illustrated Three-Line Novels: Félix Fénéon, Joanna Neborsky adds colour to the “invisibly famous” writer’s three-line novels (Nouvelles en trois lignes). ”

Inspired by Luc Sante’s English translation of Fénéon’s work for the New York Review of Books, Neborsky’s bursts of quirky colors, shapes and fonts are intriguing and captivating.

In The London Review of Books, Julian Barnes considers Félix Fénéon’s words and why he was often pictured and painted in profile, as seen above in neo-Impressionist Paul Signac’s 1908 portrait (above). This side-on view was a representation of Fénéon’s obliqueness:

“…his decision not to face us directly, either as readers or as examiners of his life. In literary and artistic history he comes down to us in shards, kaleidoscopically. Luc Sante, in his introduction to Novels in Three Lines, describes him well as being ‘invisibly famous’ – and he was even more invisible to Anglophone readers until Joan Ungersma Halperin’s fine study of him appeared in 1988. Art critic, art dealer, owner of the best eye in Paris as the century turned, promoter of Seurat, the only galleryist Matisse ever trusted; journalist, ghost-writer for Colette’s Willy, literary adviser then chief editor of the Revue Blanche; friend of Verlaine, Huysmans and Mallarmé, publisher of Laforgue, editor and organiser of Rimbaud’s Les Illuminations; publisher of Joyce and translator of Northanger Abbey. He was invisible partly because he was a facilitator rather than a creator, but also because of his manner, which was elliptical, ironic, taciturn.”

Félix Fénéon gave us challenging glimpses of complex things.

For 13 years, he worked at the War Office, rising to the position of chief clerk. Frenchly, he managed to combine this with being a committed anarchist, by both word and deed. He supported the cause as journalist, editor and – almost certainly – bomb-planter. In 1894, he was arrested in a sweep of anarchists and charged under the kind of catch-all law which governments panicked by terror attacks stupidly tend to enact. Part of the evidence against him was that a police search of his office had turned up a vial of mercury and a matchbox containing 11 detonators. Fénéon added to the history of implausible excuses by claiming that his father, who had recently died and was therefore unavailable to corroborate his evidence, had found them in the street. His defence was paid for by the artistic Maecenas Thadée Natanson, and he seems to have enjoyed matching his mind against the lawyers. When the presiding judge put it to him that he had been spotted talking to a known anarchist behind a gas lamp, he replied coolly: ‘Can you tell me, Monsieur le Président, which side of a gas lamp is its behind?’ This being France, wit did him no disservice with the jury, and he was acquitted.

Fénéon’s bon mots, says Barnes, are “Elegant variation shades into ironical euphemism, which shades into dandaical detachment”.

He knew how to shape a sentence, how to make three lines breathe, delay a key piece of information, introduce a quirky adjective, hold the necessary verb until last. Just fitting in the requisite facts is a professional skill; giving the whole item form, elegance, wit and surprise, is an art.

Dead sick of himself after reading the book by Samuel Smiles (Know Thyself), a judge just drowned himself at Coulange-la-Vineuse. If only this excellent book could be read throughout the magistracy.

A policeman, Maurice Marullas, has blown out his brains. Let’s save the name of this honest man from being forgotten.

‘Ouch!’ cried the cunning oyster-eater. ‘A pearl!’ Someone at the next table bought it for 100 francs. It had cost 30 cents at the dime store.

In the military zone, in the course of a duel over scrawny Adeline, basket-weaver Capello stabbed bear-baiter Monari in the abdomen.

A case of revenge: near Monistrol-d’Allier, M. Blanc and M. Boudoissier were killed and mutilated by M. Plet, M. Pascal and M. Gazanion.

People were beginning to think the telegraph-cable thieves were supernatural. And yet one has been caught: Eugène Matifos, of Boulogne.

This time the crucifix is solidly bolted to the wall of the school at Bouillé. So much for the prefect of Maine-et-Loire.

Mme Olympe Fraisse relates that in the woods of Bordezac, Gard, a faun subjected her 66 years to prodigious abuses.

Because of his poster opposing the strikebreakers, the students of Brest lycee hissed their teacher, M. Litalien, an aide to the mayor.

On Place du Pantheon, a heated group of voters attempted to roast an effigy of M. Auffray, the losing candidate. They were dispersed.

Mme Vivant, of Argenteuil, failed to reckon with the ardor of Maheu, the laundry’s owner. He fished the desperate laundress from the Seine.

Arrested in Saint-Germain for petty theft, Joël Guilbert drank sublimate. He was detoxified, but died yesterday of delirium tremens.

Reverend Andrieux, of Roannes, near Aurillac, whom a pitiless husband perforated Wednesday with two rifle shots, died last night.

“If my candidate loses, I will kill myself,” M. Bellavoine, of Fresquienne, Seine-Inferieure, had declared. He killed himself.

After finding a suspect device on his doorstep, Friquet, a printer in Aubusson, filed a complaint against persons unknown.

Via: Joanna Neborsky

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.