For years Federico Fellini had promised to make a film about Casanova. It was what his producers wanted, it was what they thought the public wanted. They knew the magical combination of the names Fellini and Casanova would be a box-office smash. But Fellini had no intention of making such a film as he loathed Casanova. He just hoped the promise of his directing such a production would be enough to unlock a little more finance, a little more green for all his other projects. It worked fine until the money ran out and the tax man came a-calling.

Fellini owed a small fortune in back taxes. He had spent all his money. His life was a mess. His marriage was failing and his private life was splashed across the cover of every tabloid.

He felt old. He felt weary. He feared death. Many of his friends were dead. On dark autumn nights, as the wind whipped itself around his apartment, poor Federico thought he could hear ole hatchet-faced death sharpening his old rusty scythe in the corner.

At last, Fellini was ready to make a film about Casanova.

Perhaps, he thought, making this goddam movie would make him grow up?

After this film, the moody and unreliable part of me, the undecided part that was constantly seduced by compromise—the part of me that didn’t want to grow up—had to die.

In 1973, Fellini signed-up with Dino de Laurentiis to make Casanova. De Laurentiis was a major Italian and Hollywood movie producer who had previously worked with Fellini on La Strada (1954) and Nights of Cabiria (1956). De Laurentiis wanted a big Hollywood name to star as Casanova. He suggested Marlon Brando or maybe Jack Nicholson or Michael Caine. Then decided on Robert Redford because he was the sexiest movie star in the world.

Fellini had other ideas. He wanted someone he could trust, an actor he knew he could rely on. He wanted Marcello Mastroianni. But Mastroianni said he was busy and really wasn’t quite sure whether he wanted to do it or not.

Fellini began work on the script with his longtime collaborator Bernardino Zapponi. Zapponi had read all of Casanova’s memoirs and intended to write a true and faithful adaptation of the great lover’s life. Fellini had no such intention. He was only interested in making a film about Fellini and his obsessions than a dull biography of Casanova.

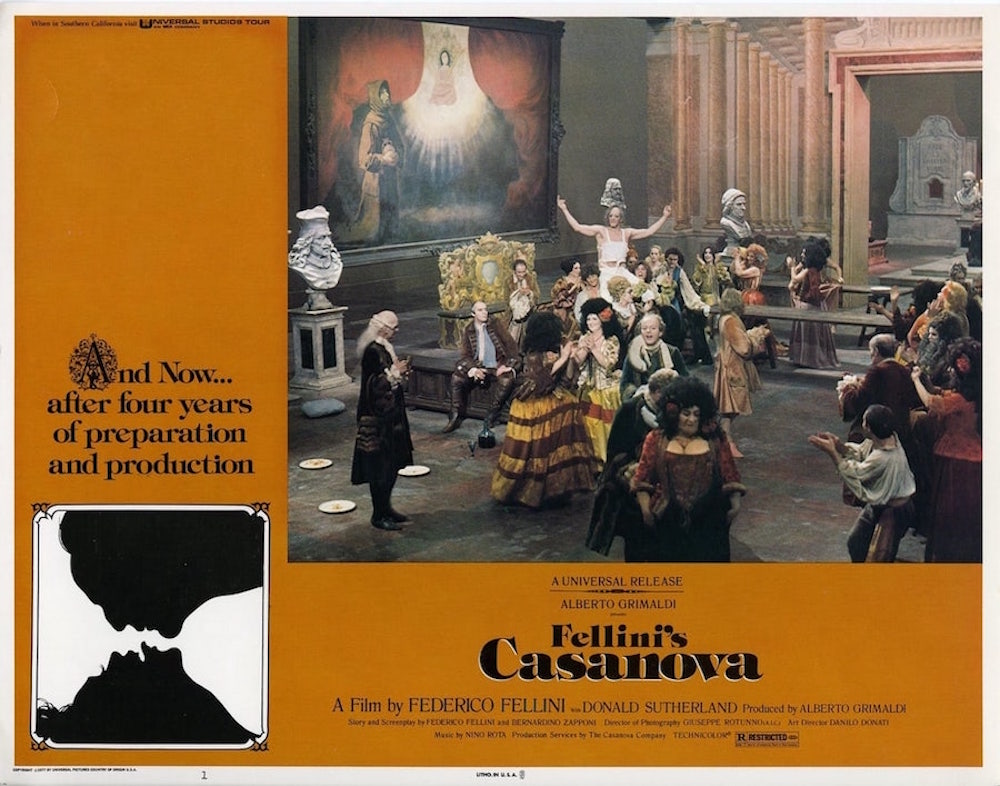

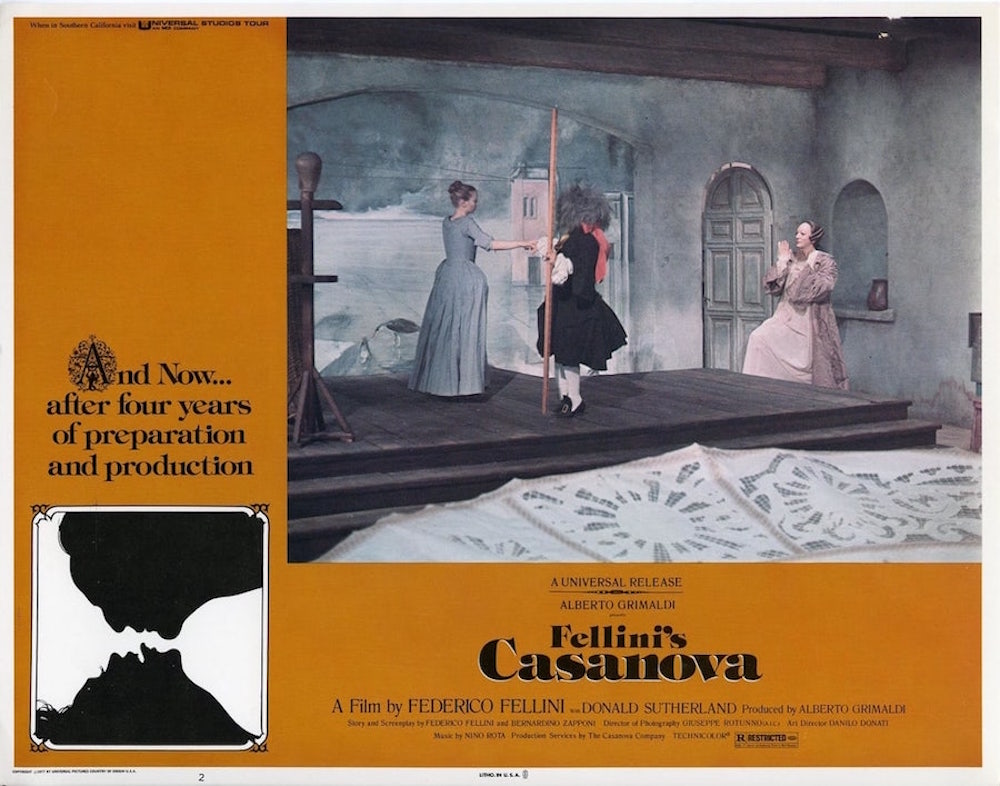

When de Laurentiis found out what Fellini had planned in July 1974, he decided not to produce the film. Fellini panicked. He scrabbled around to raise money to save the project. He convinced Universal Studios to back the picture on the basis of a script he asked Gore Vidal to write. But Fellini never used Vidal’s script. Then producer Alberto Grimaldi stepped into the breech and Fellini’s Casanova was back on track.

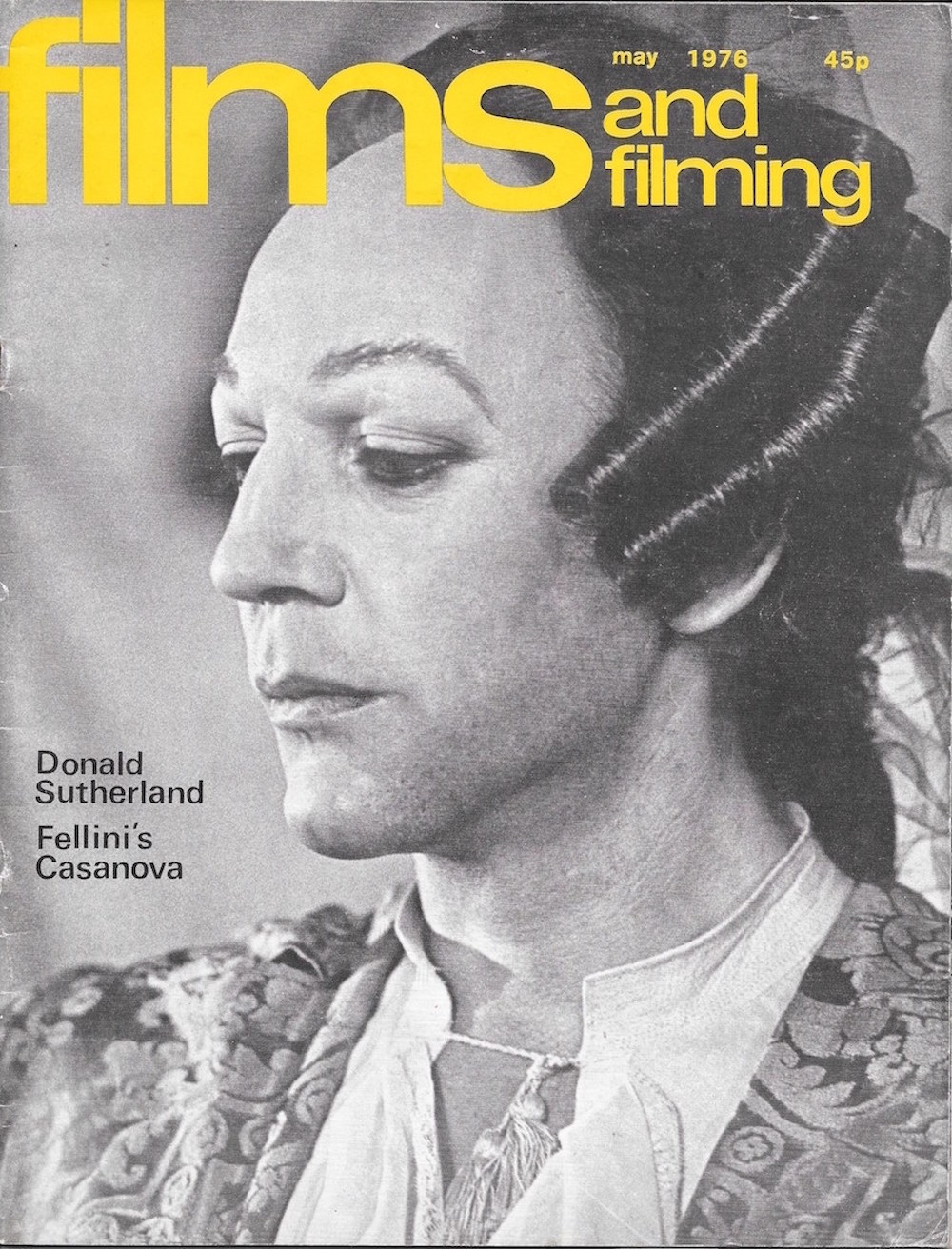

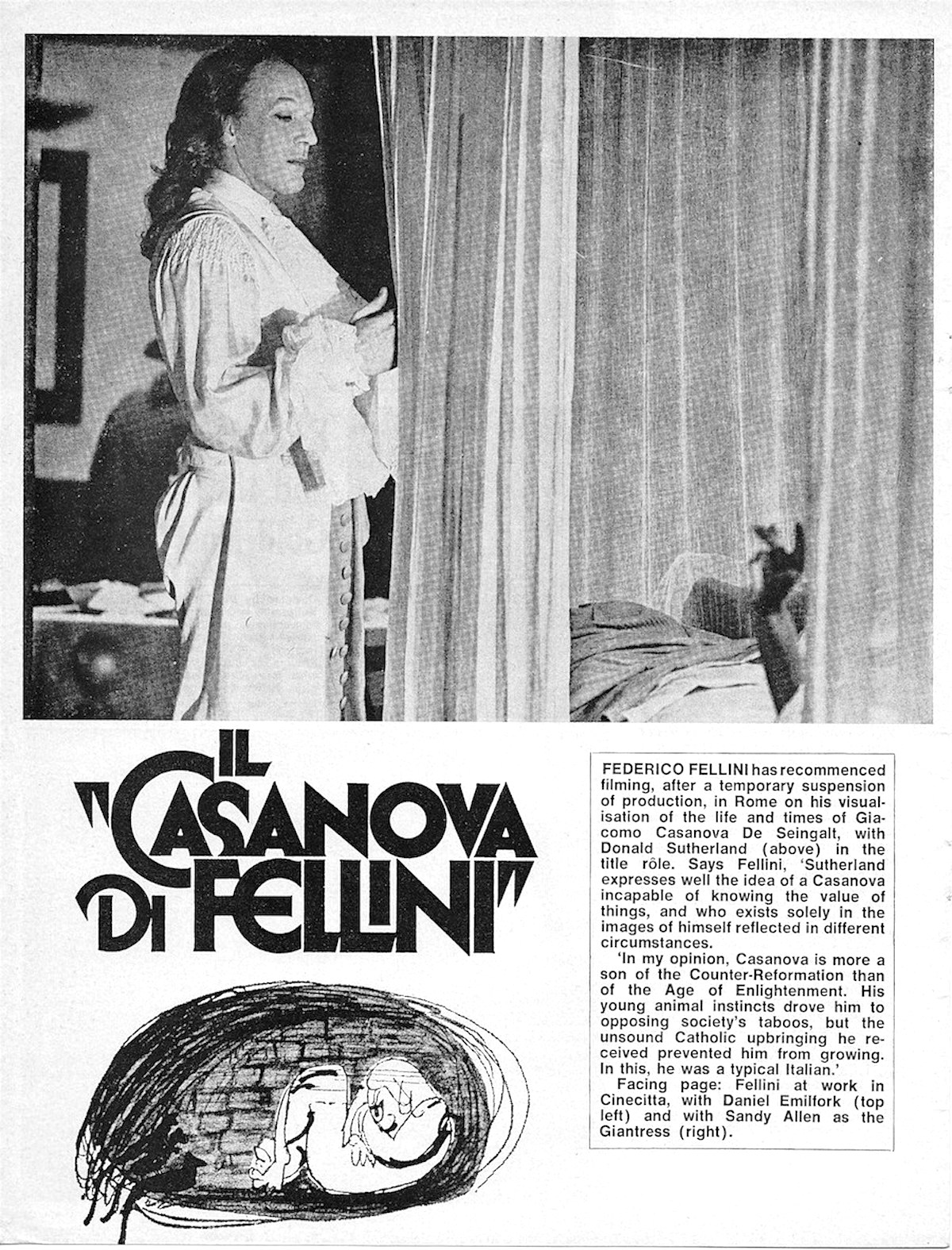

There was still the question of who was to play the lead. Mastroianni still claimed he was too busy. No one else seemed to fit. Then rumours went around (from whom no-one ever seemed quite sure) that Donald Sutherland wanted to play the part. The pair met. Fellini had his new Casanova.

Fellini later said:

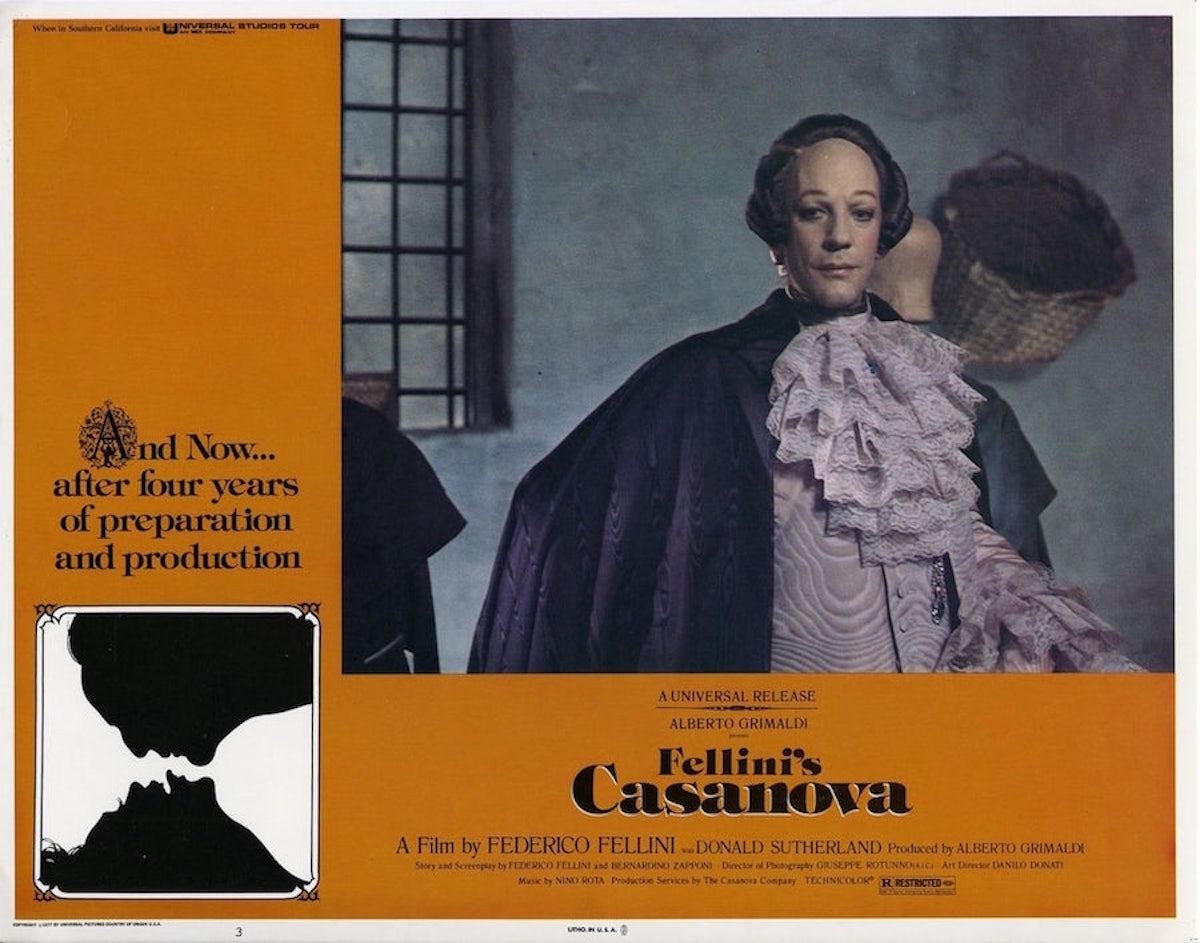

It seemed to me that Donaldino’s [Donald Sutherland] face was perfectly adapted to the image of an Italian who was unripe, juvenile, a kind of Pinocchio-in-the-uterus, which was the image I had of the real Casanova whom I considered a stronzo or fool, an idiot.

Only a great professional actor like Sutherland could incarnate such negative qualities effectively. In addition, Don has fabulous blue eyes.

As my Casanova, these eyes expressed the sterile masturbatory fantasies of the voyeur, of a walking sperm bank suffering from chronic insomnia.

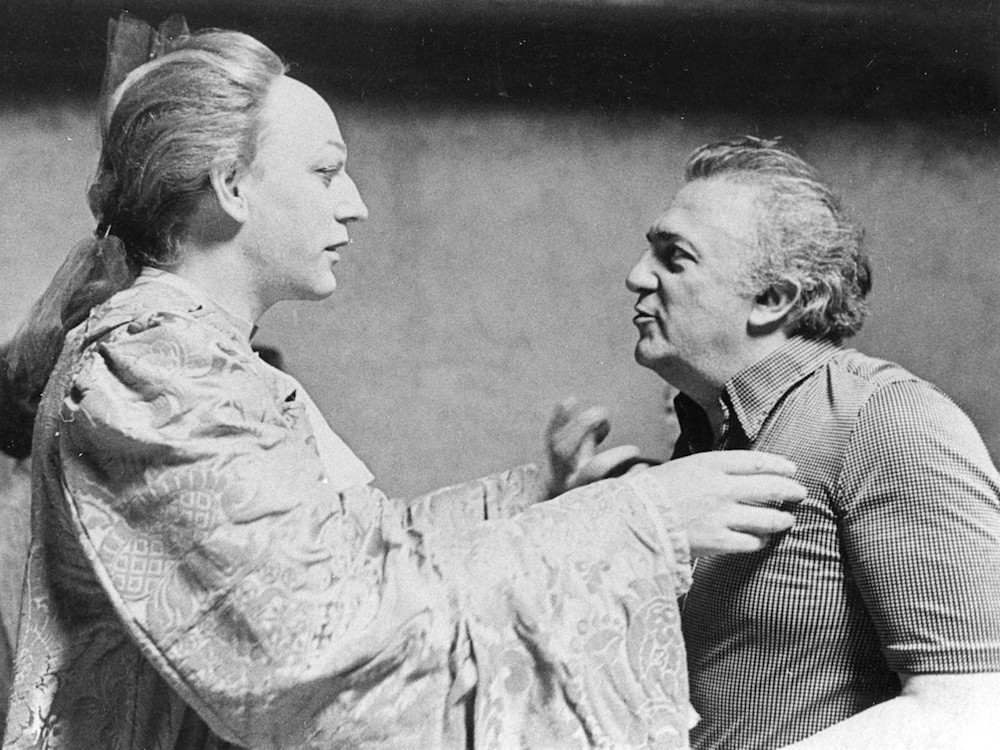

For such a perfect Casanova, Sutherland still had two millimetres filed from his teeth, his eyebrows removed and his hairline shaved by two inches. He wore a prosthetic nose and chin. Fellini had basically turned Sutherland into a puppet—a mere mechanism for telling his story.

Fellini explained his intentions in I am a Born Liar–A Fellini Lexicon:

The real Casanova was never properly born, which is the meaning of the film’s opening when the gigantic black head of Venus with starring, goitrous eyes rises to the surface of the Grand Canal as the carnival crowd chants, “Fornicating cunt, defecating ass, subterranean old hag, stinking old woman!” And the pulleys snap. The great female head sinks to the bottom of the Venetian lagoon, like a miscarriage or an abortion. But her eyes never close: they remain fixed on the void, eyeless in Gaza.

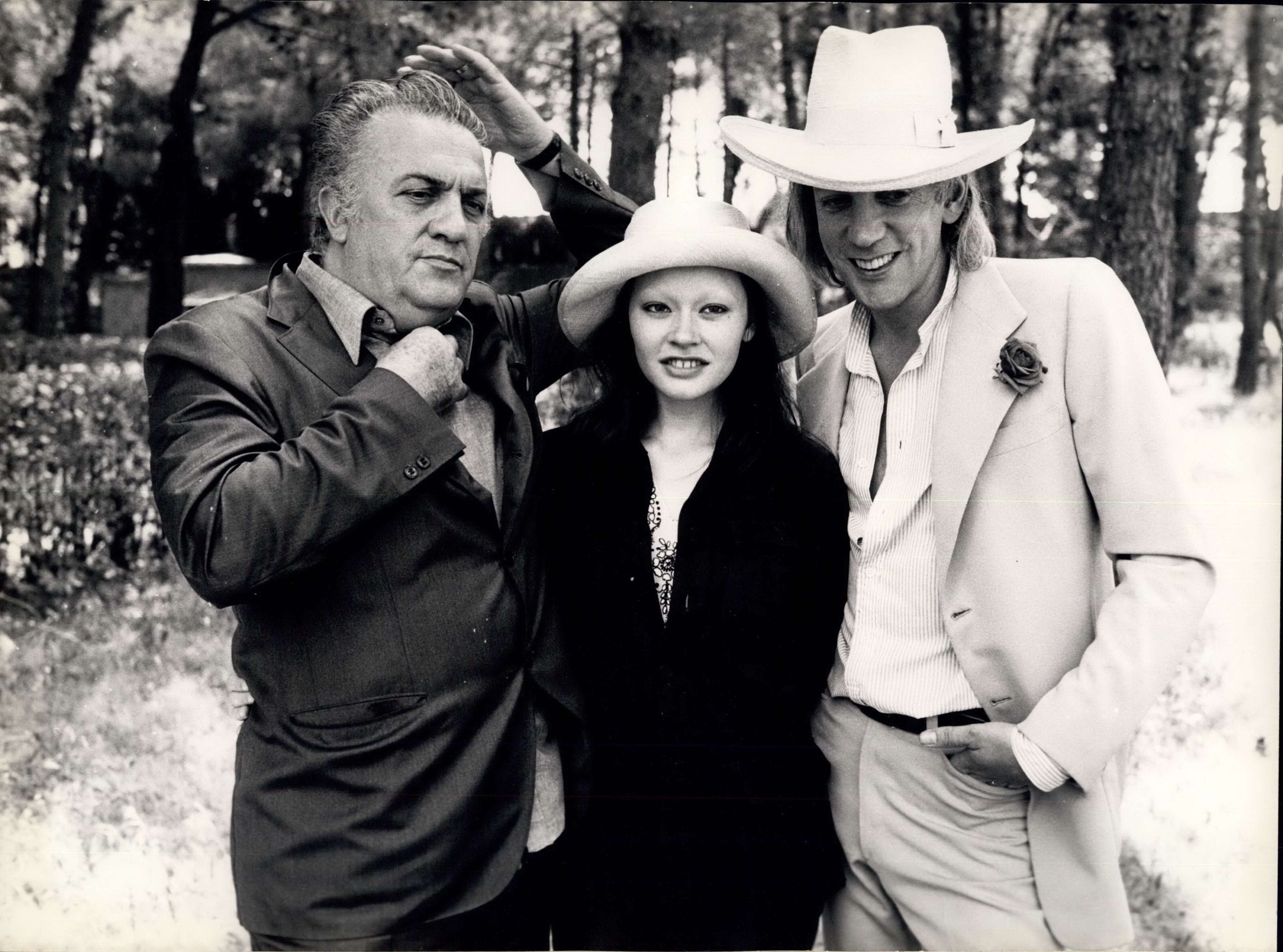

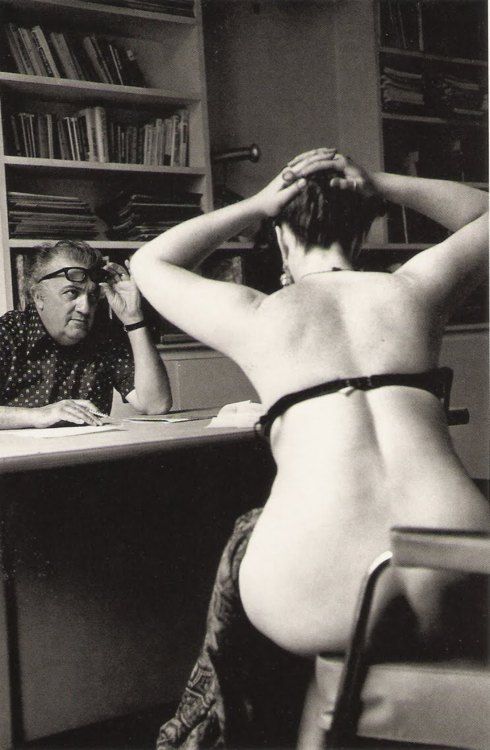

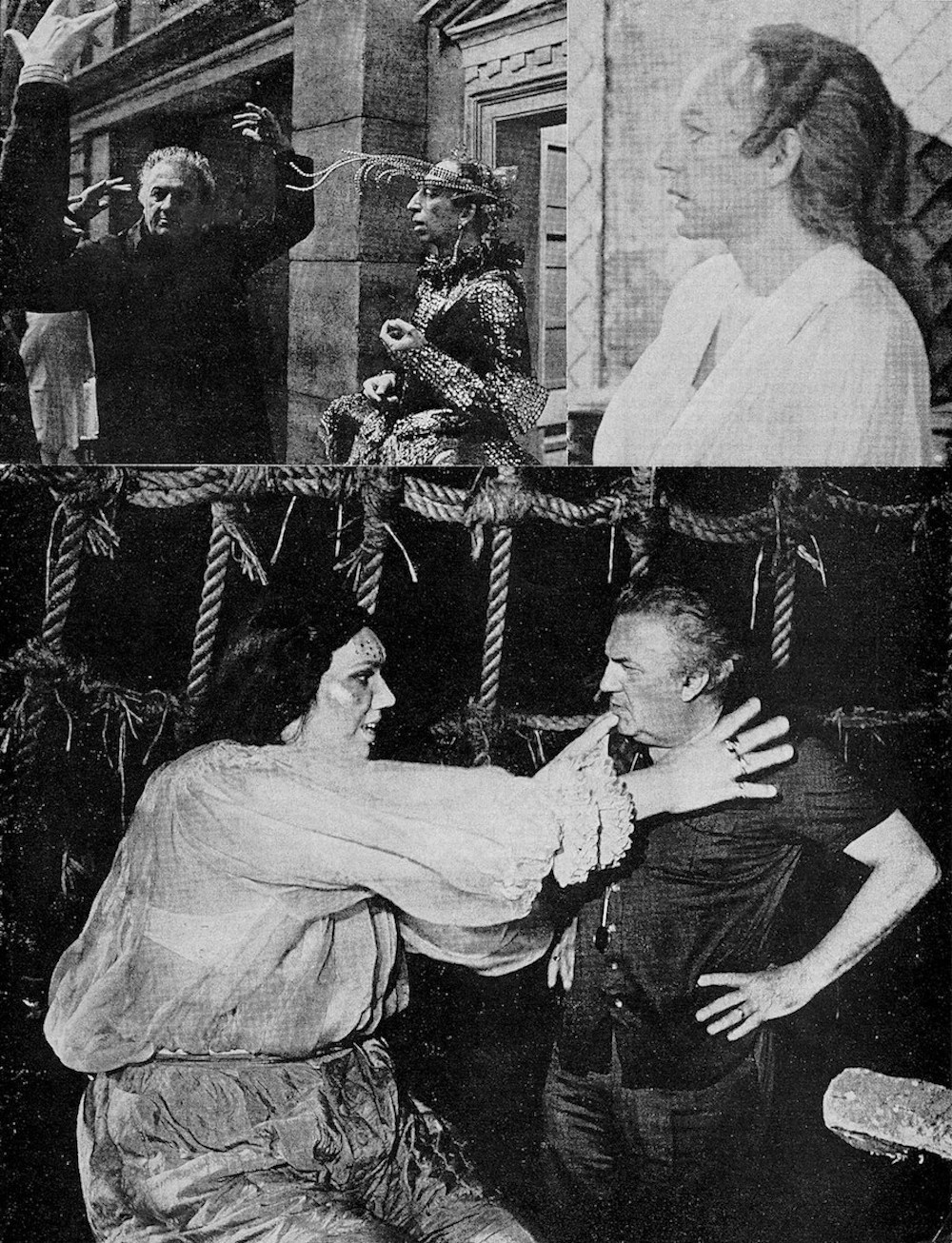

Federico Fellini. Casting for Il Casanova di Federico Fellini, 1975

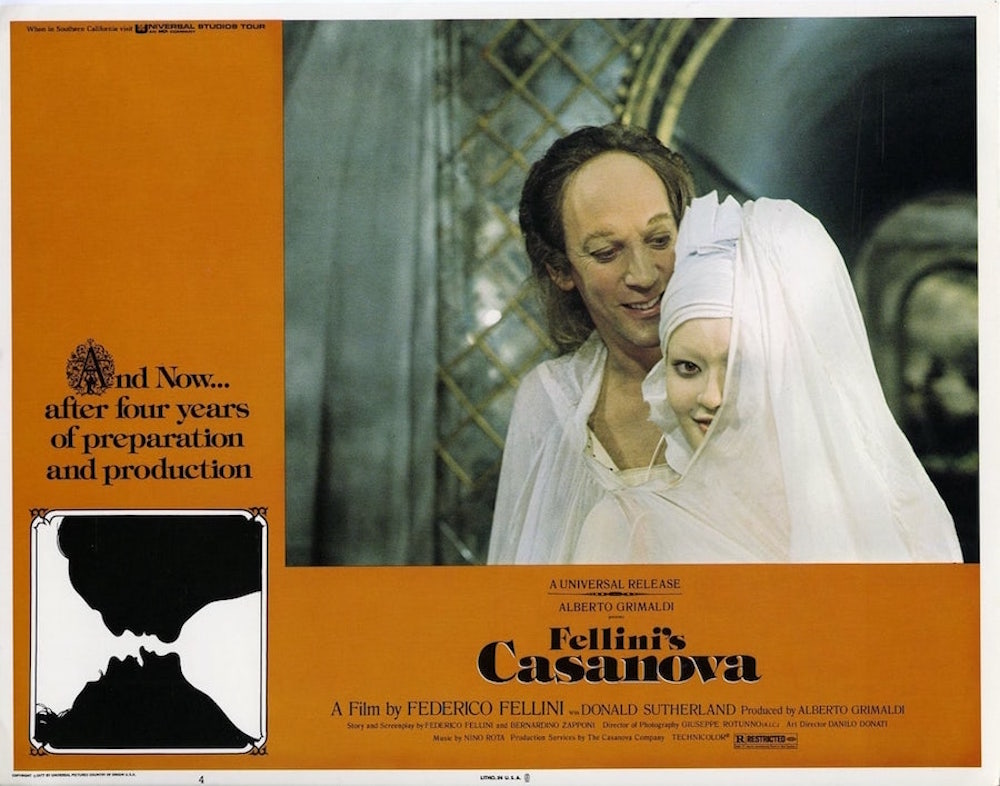

Federico Fellini and Donald Sutherland on the set of Il Casanova di Federico Fellini, 1976

Filming proved difficult. Fellini felt he was being cursed by Casanova’s ghost:

It’s a film that cost me dearly. Every day for three years, I inspected the wrinkles of a thousand extras. Never worked so hard in my life. We were plagued by nothing but well-publicized accidents and catastrophes. Even the end of production had Don [Sutherland] collapsing in the field where we’d shot the last brief scene with Venice frozen in the ice. Solemnly removing his false nose and chin, he walked out over the uneven field waving his huge black cape in a final salute when suddenly he disappeared. The heavy cape had dragged him down. He got up, waved, and fell down again. He was put through supernatural trials that would have discouraged the likes of Indiana Jones.

I’m convinced that the real Casanova was persecuting us for my having ruined his reputation. But what could I do? You can’t imprison a ghost.

Despite some fine performances, some beautiful set-pieces and one of the greatest film scores by Nino Rota, Fellini’s Casanova lacks soul. Sutherland had “the unenviable task of attempting to deliver an intelligent and considered performance to a director who only wanted a marionette to play the role.”

The movie was a flop with critics and did average business at the box office. It deserved better but ended up being a film to be admired rather than liked.

Fellini disagreed. He thought the film “courageous” as it taught him “the absence of love is the worst suffering anyone can endure.”

H/T Dangerous Minds.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.