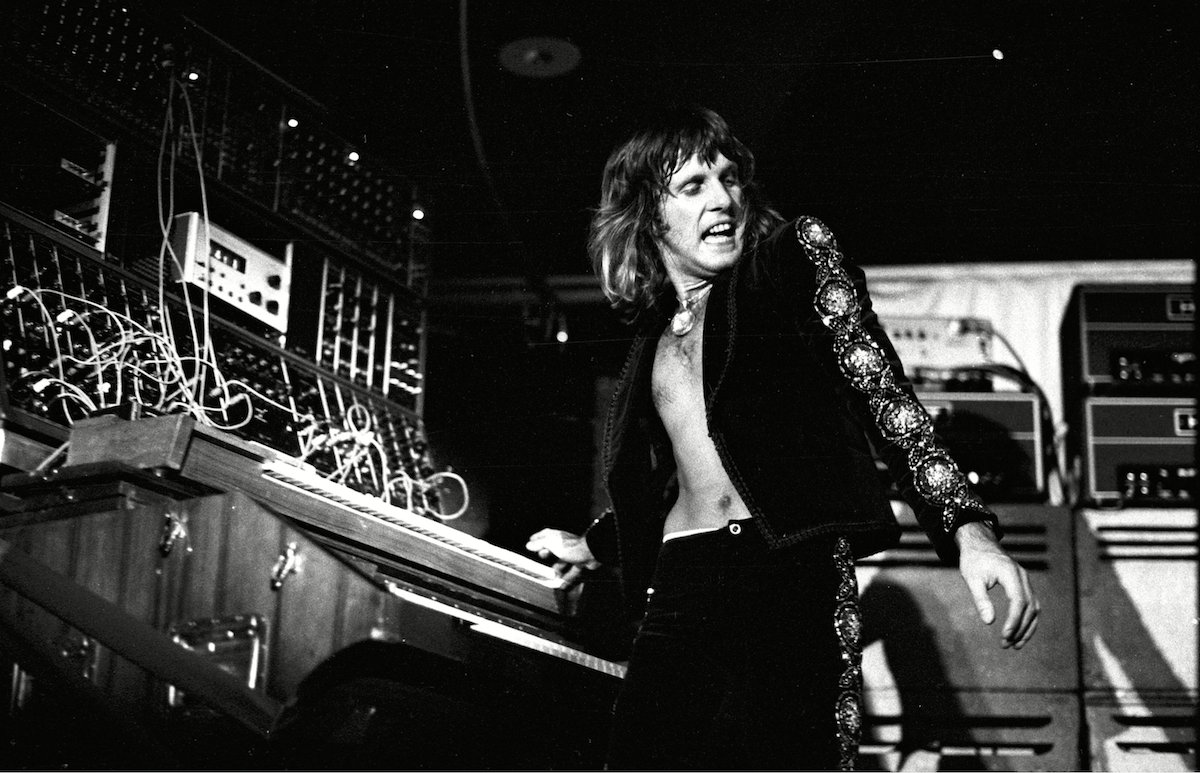

Keith Emerson performing live on his Moog modular synthesizer

In the summer of 1970, after popping into a pub for a pint, rock keyboardist Keith Emerson sat down at his enormous Moog modular synthesizer in London’s legendary Advision recording studio and noodled a few improvised notes. His goal was to add some electronic punch to the end of a mostly acoustic-guitar number called Lucky Man, written by his singer-guitarist bandmate, Greg Lake. As his fingers ran up and down the synthesizer’s keyboard, Emerson played along to the bass, drums, vocals, and guitars already recorded by Lake and drummer Carl Palmer. Their contributions were lovely, imbued with the traditional rhythms and melodies of folk music and warmed by the human voice. In contrast, Emerson’s notes were otherworldly, rising and falling in syrupy sweeps, as if propelled through a rollercoaster of resonant tubes.

Emerson would later say he was just fooling around, and that he definitely did not expect his first take to be his last, but Lake and sound engineer Eddie Offord liked what they heard so much, they deemed Emerson’s work on “Lucky Man” done.

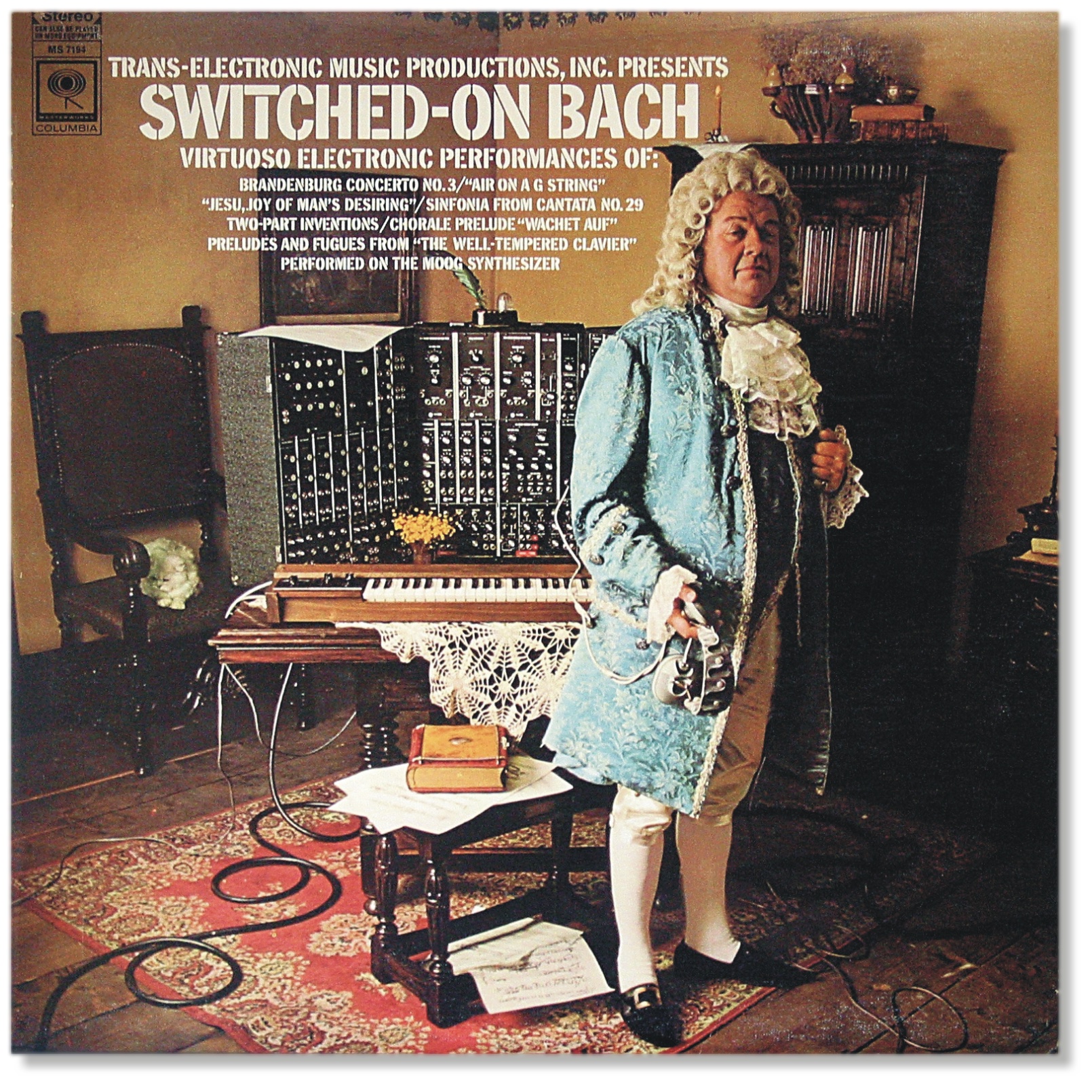

Until that moment, classical music had been the genre of choice for aspiring synthesizer musicians like Wendy Carlos, whose 1968 album, Switched-On Bach, was recorded almost entirely on a Moog modular synthesizer, which had only been introduced in 1964. Switched-On Bach became a surprise hit, but it was the subsequent appearance of Lucky Man on international pop charts that helped make the synthesizer a favorite of rock musicians, too, and propelled Emerson, Lake & Palmer to stardom.

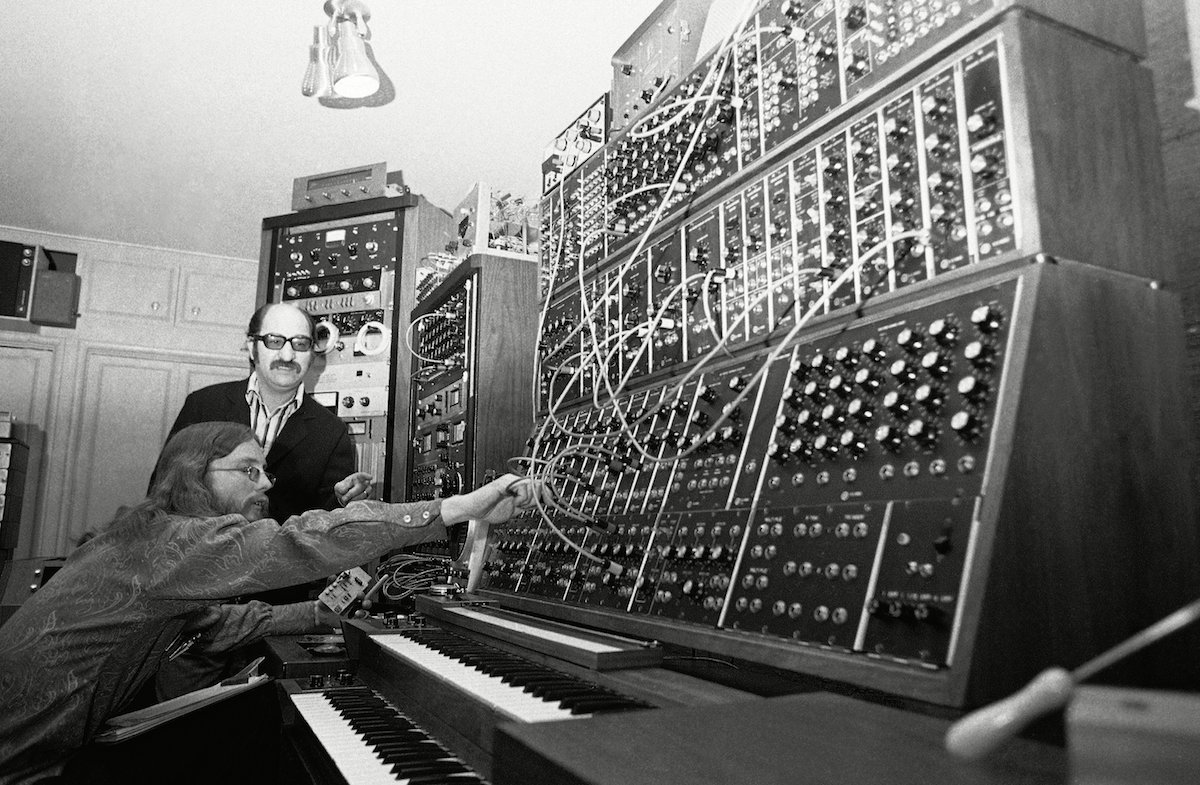

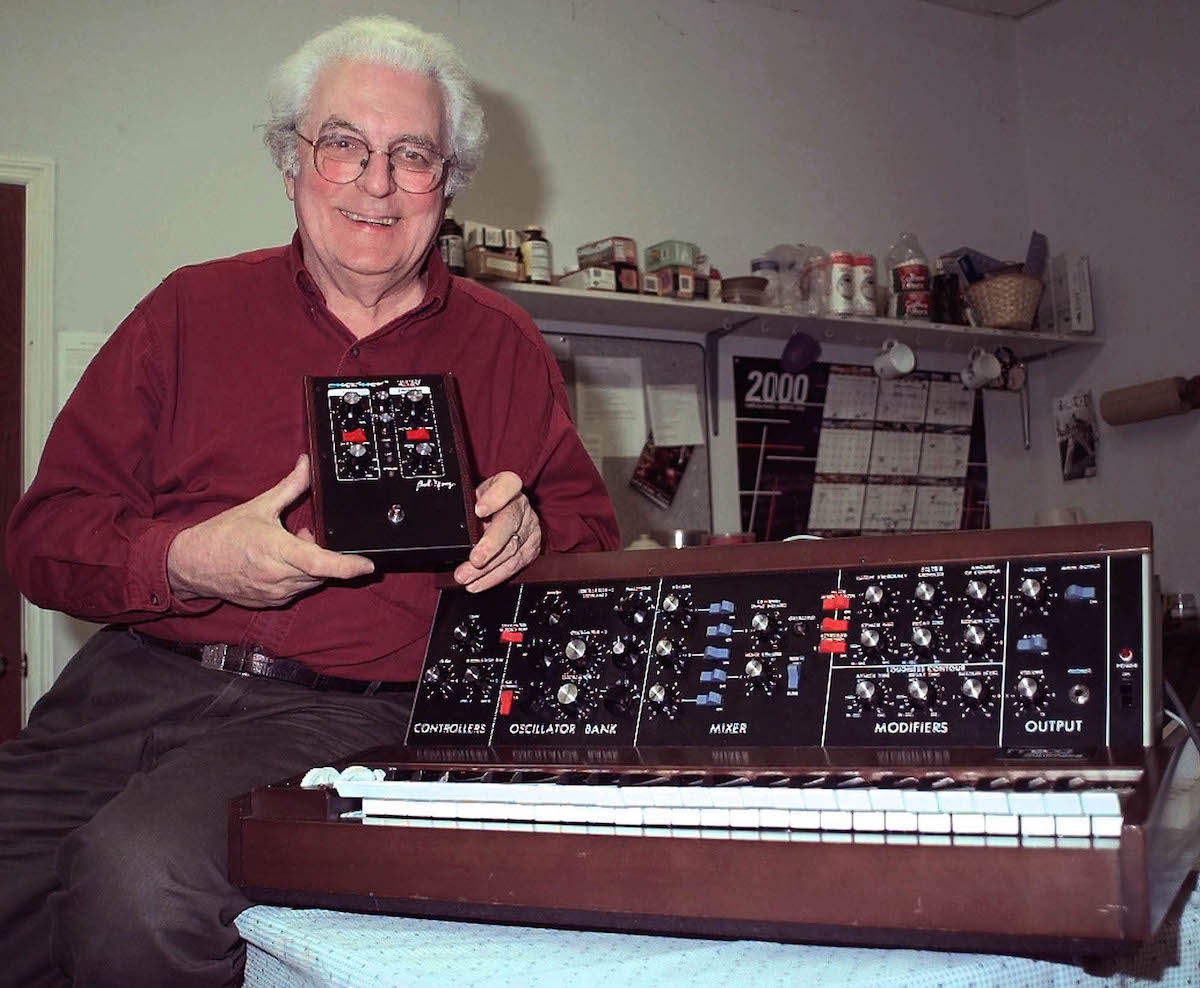

Robert Moog, 35, who designed the best known of the electronic musical synthesizers, makes final adjustment on the Moog Synthesizer prior to a jazz concert at Museum of Modern Art, New York. Two quartets played four Moogs during the hour and a half long concert in the Museums open air sculpture garden. Some 4,000 persons attended the concert

Robert Moog 1969, New York, USA

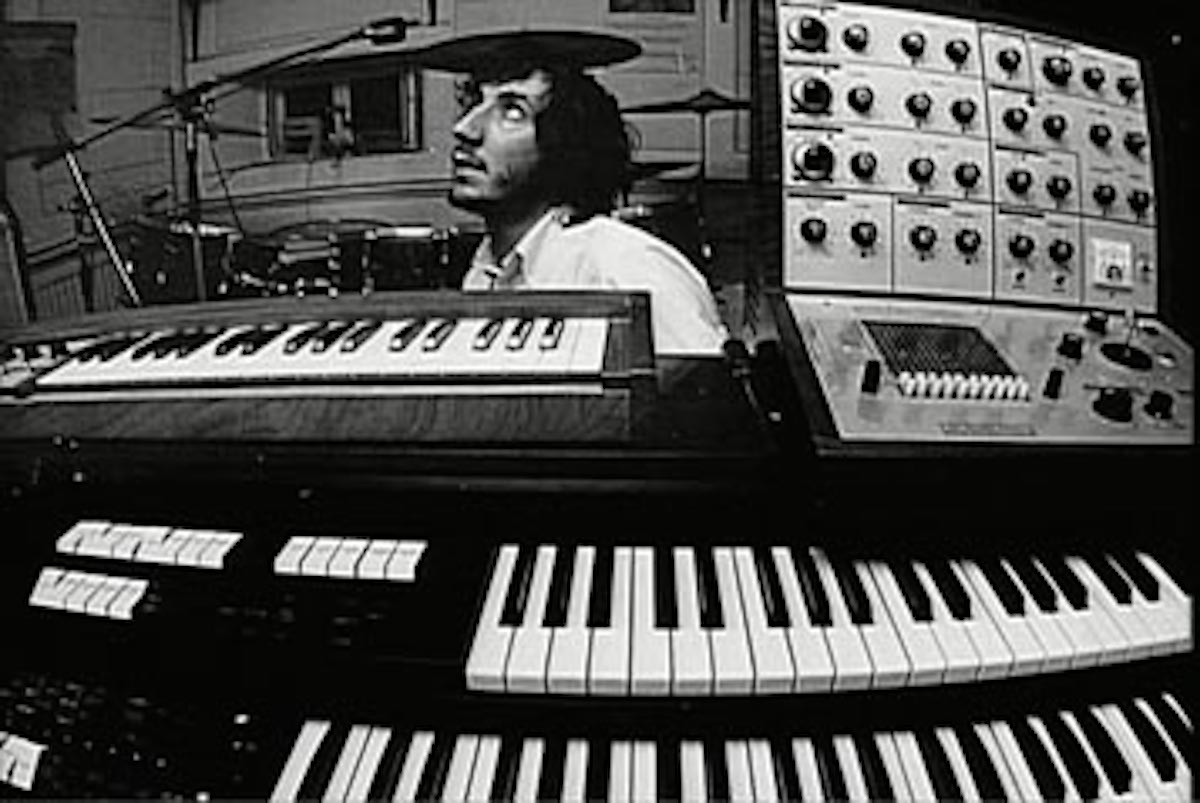

Pete Townshend in his home studio, with an EMS VCS 3 (at right) sitting atop his Lowrey organ.

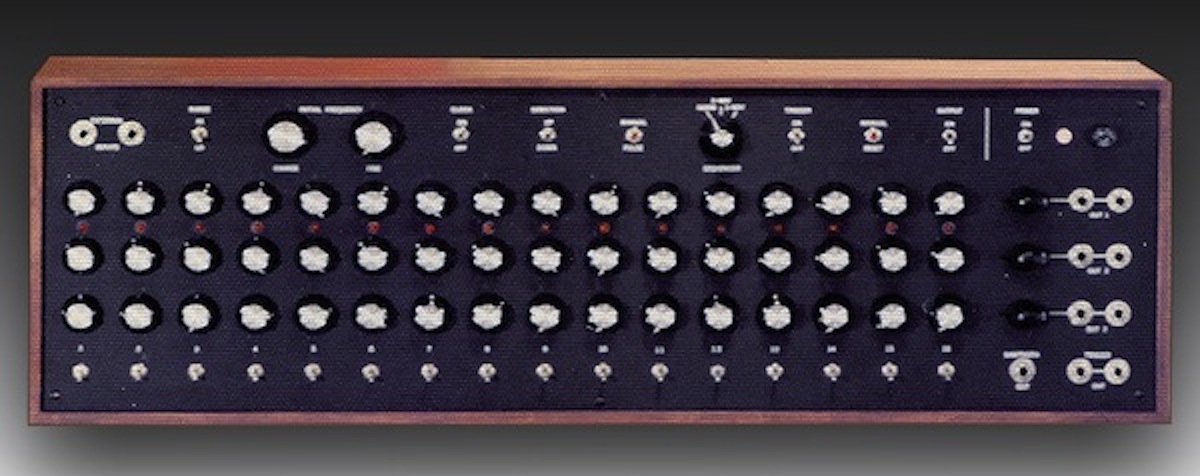

The following year, in 1971, Pete Townshend of The Who patched a few simple chords played on a regular Lowrey organ through an EMS VCS 3 synthesizer to produce the bouncy, almost shivering, sequence that introduces and closes Won’t Get Fooled Again. And by the summer of 1972, Pink Floyd would use an EMS Synthi AKS, as well as the VCS 3, on just about every track of its Dark Side of the Moon album, cementing the synthesizer’s reputation as an instrument that knew how to rock.

Today, nobody would question that assertion, since synthesizers are bigger than ever in just about all musical genres, from contemporary ambient and techno to the revival of 1980s synthpop. Northern California has become a particular hotbed for the instrument. In Oakland, a musician named Lance Hill has opened a studio called the Vintage Synthesizer Museum, and in San Francisco, one of the biggest names in synthesizers of the 1970s and ’80s, Dave Smith, is once again selling instruments bearing the Sequential brand.

Back when Pink Floyd was recording synth-heavy songs like On the Run, Smith was half a world away at the University of California at Berkeley, where he was studying computer science and electrical engineering. Today, those majors would be savvy career decisions, but for him the subjects came naturally. “I was just kind of going through the motions,” Smith admitted recently when asked if his degrees presaged his rise as one of the leading synthesizer inventors and manufacturers of the 1970s and ’80s. “Back then, engineers were not in demand,” he explains. “The Silicon Valley as we know it today hadn’t really started. Most of the engineering jobs were in aerospace.”

Switched On Bach, 1968

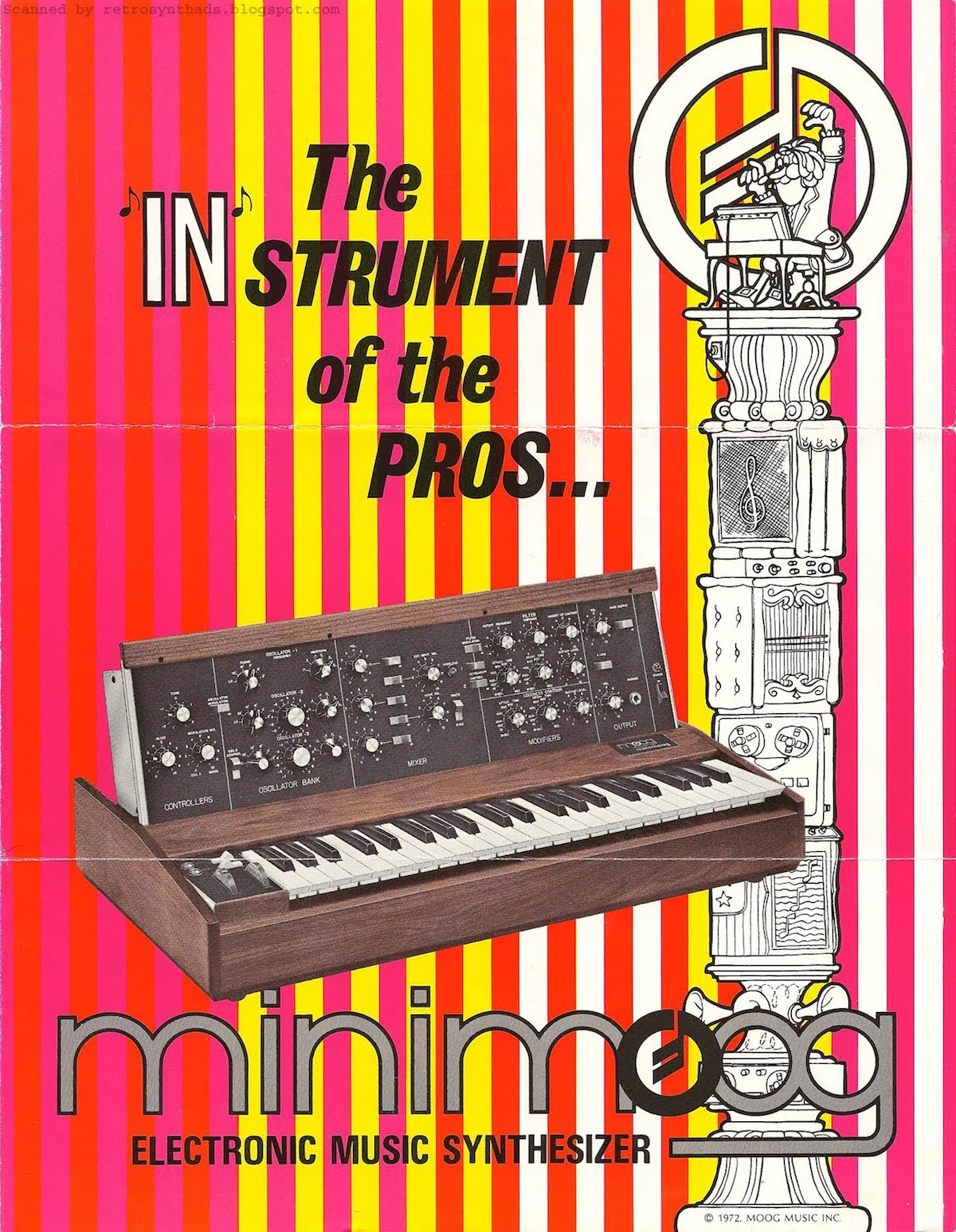

Just because Smith wasn’t interested in becoming a rocket scientist doesn’t mean he was an unproductive layabout. A garage-band-caliber musician, Smith purchased a Minimoog in 1972, marrying his interest in music with his comfort around electrical circuits. Eventually, by 1974, Smith had built a 16-step sequencer for his synthesizer, allowing him to program runs of repeating notes, whose timing and tone could be adjusted on the fly. “Moog made its own sequencers,” Smith says, “but they were expensive and hard to find. Sequencers were just fun things to play with, so I decided to build one that would do exactly what I wanted.”

The fact that Smith was motivated to spend his evenings and weekends building a sequencer from scratch, and that companies like Moog felt compelled to offer such add-on modules to their customers, says a lot about the state of the synthesizer in 1974.

In a word, synthesizers in 1974 sucked. Sure, their vintage cred looks cool from 2015, but all synthesizers in 1974 were monophonic, which meant they could only produce one note at a time. That was a major headache if you were Wendy Carlos and you had made it your mission to include a composition such as Johann Sebastian Bach’s Brandenburg Concerto No. 3 on Switched-On Bach. Because her Moog was monophonic, Carlos had to play the notes for each of the concerto’s nine stringed instruments—as well as the harpsichord part—one at a time. Worse, Carlos was forced to play each note in each of the chords any of those instruments might be required to produce one at a time, too.

his array of keyboards, patch cords, knobs, dials, flashing lights and tape recorders is called a Moog synthesizer, a device which Mort Garson, rear, says an simulate any sound, musical or nonmusical. Operating the equipment is Gene Hamblin, . There are several hundred similar devices, made by Robert Moog of Trumansburg, N.Y., around the country, mostly in colleges teaching electronic music. 27 Jan 1971

A 1972 brochure for the Minimoog.

As if that limitation were not hobbling enough, early synthesizers, including the Moog, were notoriously bad at staying in tune, which meant Carlos typically had to work in bursts—often lasting no more than 5 seconds at a time—before the tone she had found by twisting one knob this way and another that way had degraded. Once a clean burst was recorded, the tape would be rewound, cued up, and the next burst would be added in real time. It was a painstaking procedure, requiring endless takes. In retrospect, that a project like Switched-On Bach was completed at all is something of a miracle.

If synthesizers were so much trouble, why did the best musicians on the planet, as well as mere mortals like Dave Smith, find them so intriguing? Well, it probably had something to do with the fact that sounds ranging from a pebble splashing in a pond to a runaway locomotive crashing into a glass factory were impossible to produce on a guitar or piano. For synthesizers, though, such sounds were just the tip of a very large electronics iceberg.

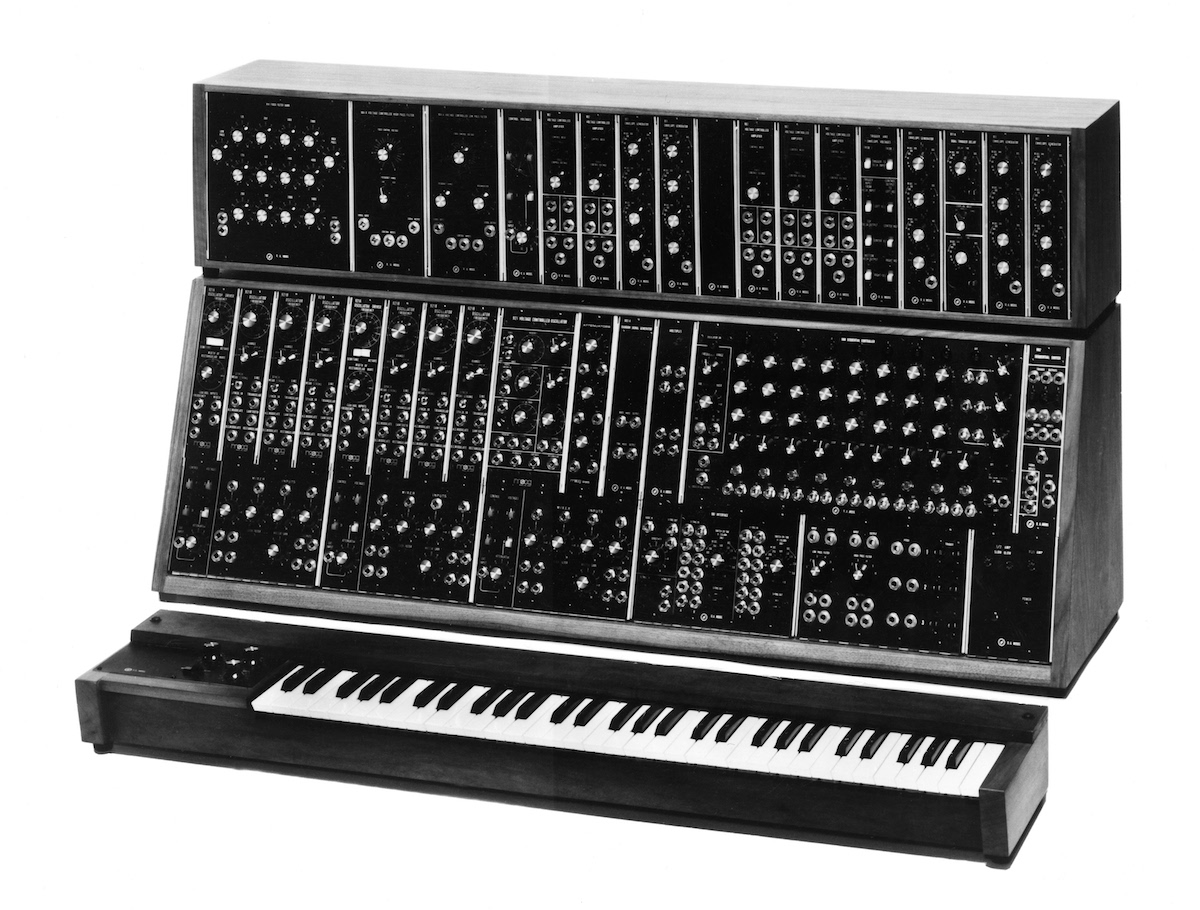

Unlike an iceberg, though, whose ocean-liner-sinking mass is hidden from view, the guts of synthesizers, or at least a musician’s access to them, are there for anyone to see, if not to immediately comprehend. For example, when fans attending an Emerson, Lake & Palmer concert in the 1970s looked up at the stage in the direction of Keith Emerson, what they typically saw was a shaggy haired keyboardist dwarfed by a mad-scientist’s tangle of patch chords and knobs. How could anyone “play” a machine like that, many of these fans must have wondered?

Emerson, Lake and Palmer – Keith Emerson . 1970s

The architecture of a typical analog synthesizer. Via Pykett.org.

In fact, for all their complexity, synthesizers are fairly straightforward devices. At their heart is something called a voltage-controlled oscillator, or VCO. As its name might suggest, a VCO allows a musician to vary the voltage of the signal, or current, coming into the instrument, thus changing the shape of its subsequent waveform, or oscillation, which is the primary source of a synthesizer’s sound. Some VCOs produce clean tones, which you’ve perhaps seen visualized on science-museum oscilloscopes as rolling sine waves. The sound of a tuning fork resembles a sine wave when visualized on an oscilloscope, while a bow being pulled across violin strings looks more like a sawtooth. Drums produce squares; flutes make triangles. Most synthesizers are equipped with several VCOs—Keith Emerson’s Moog had three.

From there, the sound usually passes through one or more filters to give the raw noise created by the VCO some color, or “timbre.” The sound will also travel through a voltage-controlled amplifier, or VCA, which increases or limits the sound’s intensity, or “gain.” At some point, the sound may also pass through an envelope generator, which allows the musician to control the sound’s “attack,” or how quickly it reaches its peak; “decay,” how quickly it falls from that spike; “sustain,” how long the sound plateaus; and “release,” how long after that it disappears entirely. And then the sound is often fine-tuned by being patched into a low-frequency oscillator to create effects such as tremolo and vibrato.

If you are Keith Emerson noodling around in a London studio on a summer’s day, you may also add portamento, which is what made the notes he played on “Lucky Man” sound like they were slipping and sliding into one another.

Dave Smith’s first product for the company that became Sequential Circuits was a 16-step sequencer, which he built in 1974 as an add-on for his Minimoog.

Moog Synthesizer, C1975. Moog Synthesizer, System 55. Photograph, C1975.

Moog Synthesizer, C1975.

What’s weird about the process of making music on synthesizers is that they achieve their sounds through something known as subtractive synthesis. In other words, it’s not only a matter of building sounds by adding layer upon layer—it’s actually more important to systematically restrict the sounds one is creating through the judicious use of filters, and by throttling rather than increasing amplification. Seeing what happens when you turn all the knobs on a synthesizer to 11 can be interesting, but it’s rather like pouring a shot of everything in a bar into an enormous tumbler and then taking a great big gulp. Unless your goal is to wake up in a Soho doorway, to borrow a lyric from Pete Townshend, you’d do better to mix, sip, and savor a perfectly balanced cocktail. When it comes to synthesizers, less is just about always more.

Except, of course, for Smith, who did want more, at least when it came to seeing how far he could push his products. “Originally, it was just for my own use,” Smith says of what became his Model 600 Analog Sequencer. “Then, once I got it done, I realized maybe some other people might want it, too. That’s when I formed Sequential Circuits. There wasn’t a big master plan,” he adds. “I just kind of backed into it.” Thus the Model 600 Analog Sequencer of 1974 laid the groundwork for the Model 800 Digital Sequencer of 1975. It was roughly the same machine as the 600 except for its digital circuitry and storage capabilities, which meant those 16-step sequences could be saved and played back later. Believe it or not, in 1975, this was a big deal.

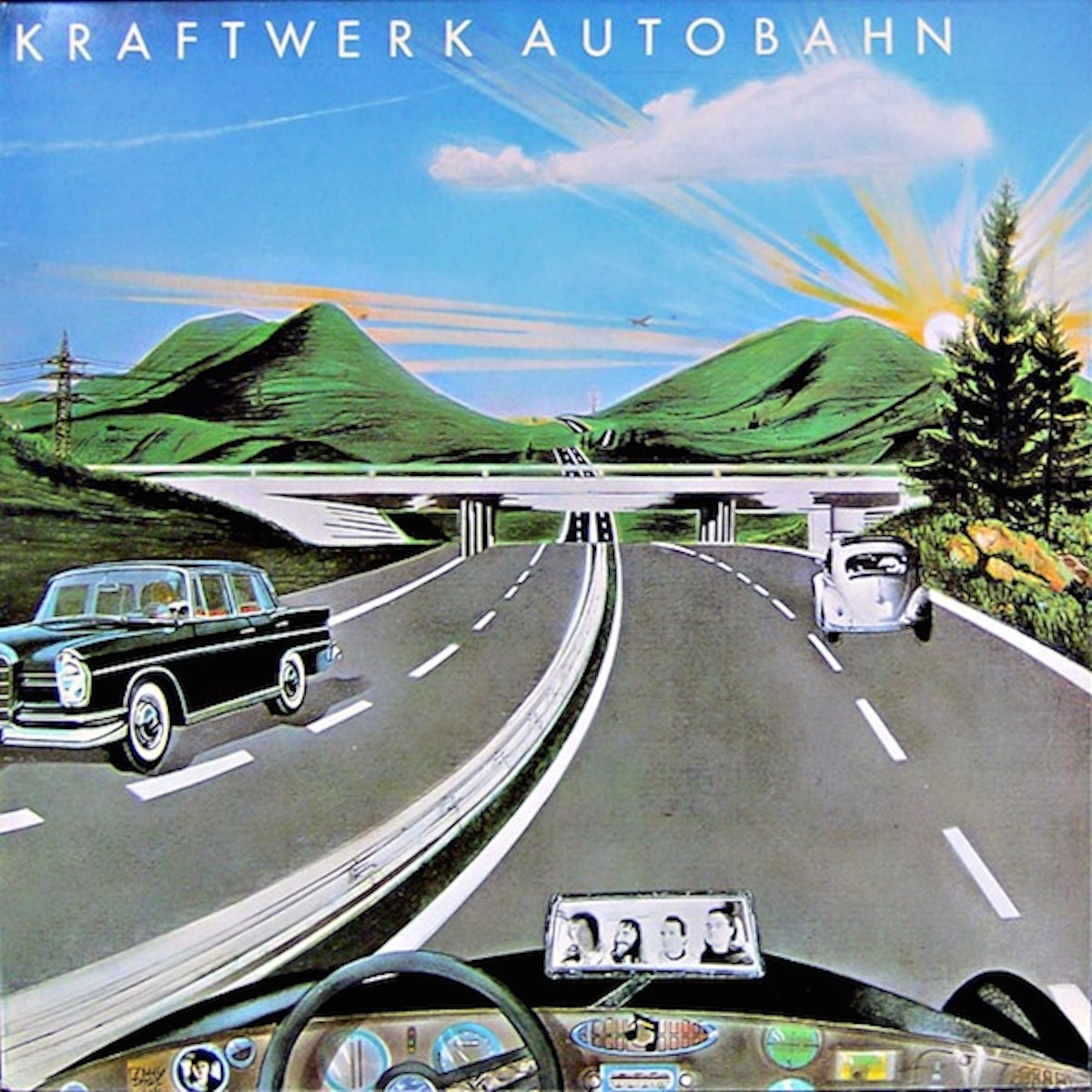

The members of Kraftwerk used a Minimoog, ARP Odyssey, and EMS Synthi AKS on their 1974 breakthrough album, “Autobahn.” =

Naturally, Emerson, Townshend, and Smith were not the only ones in the early 1970s intrigued by the potential of synthesizers in popular music. In 1974, a German electronic-music band called Kraftwerk had made extraordinarily good use of the Minimoog, ARP Odyssey, and EMS Synthi AKS that were kept at the ready in the band’s Kling Klang Studio in Düsseldorf for an album called Autobahn, whose eponymous hit single would add the term “Krautrock” to the musical lexicon.

Still, advances in technology were changing more than just music. South of San Francisco, the Silicon Valley that only a few years before had been dominated by the aerospace industry was suddenly poised to be a proving ground for what would become the personal-computer revolution. Among the region’s watershed moments was the first meeting of the Homebrew Computer Club in March of 1975. Hosted in the garage of a programmer named Gordon French, the meeting was attended by a computer engineer named Steve Wozniak, who, with the marketing and sales support of his friend Steve Jobs, released the first Apple computer in the summer of 1976.

In short, the musical-synthesizer revolution was taking place at the exact same moment as the dawn of the personal computer. What was a computer science and electrical engineering graduate to do?

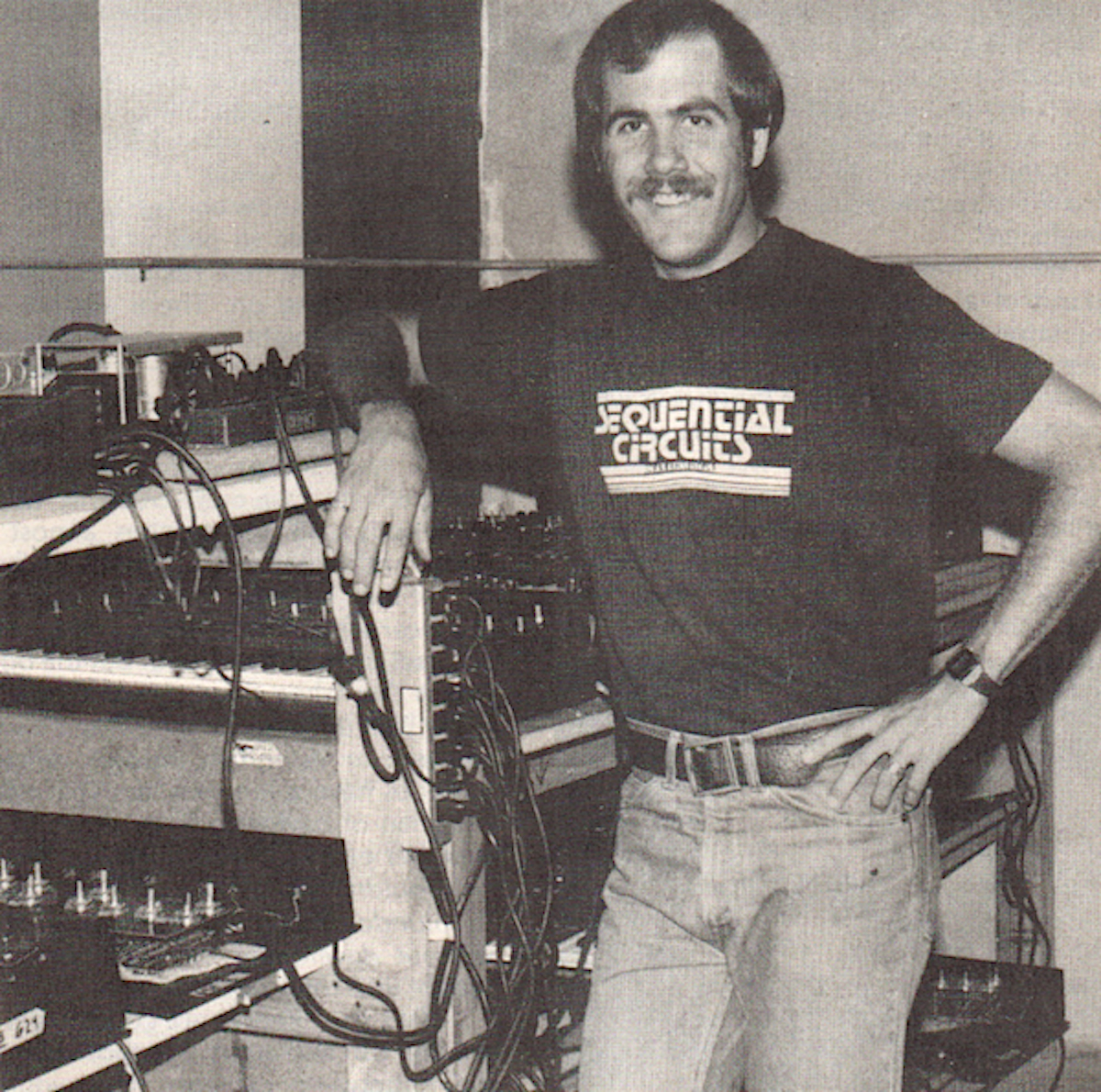

Dave Smith at Sequential Circuits in San Jose, circa 1978.

As it turns out, Smith was not completely divorced from events taking place around him, and had been keeping an eye on both developments, as the geeky name of his San Jose, California, company suggests. “Obviously, my first product was a sequencer, so that’s where the ‘Sequential’ part came from. I don’t remember why I came up with Sequential Circuits, although there is such a thing as a ‘sequential circuit.’ At the time, though, I wasn’t sure I was going to continue to have a company, and if I did, I didn’t know if it was going to be about musical instruments or not. Like probably a hundred thousand other people, I had an idea about getting a microprocessor and putting it in a box with a little screen and a couple of floppy discs. So, I wanted to keep the name somewhat vague, rather than using my own name or a music-oriented word.”

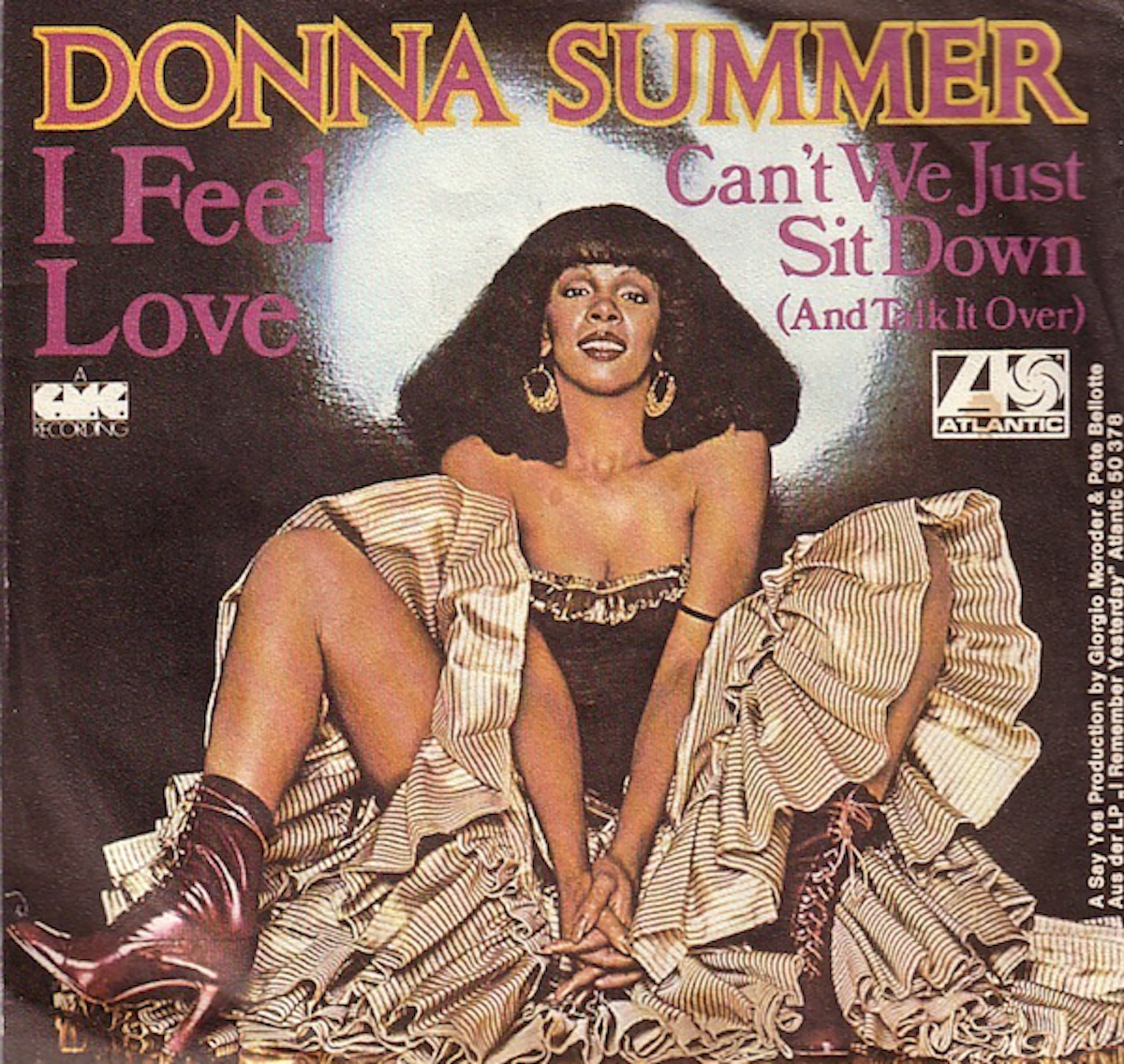

Smith can be forgiven for having reservations, because at the same time that synthesizers were being embraced in the mid-1970s by the prog, Kraut, and classic rockers, they were being rejected by a new, noisy contingent called punk, which viewed the artificial sounds synthesizers produced with undisguised scorn—it’s difficult to imagine a synthesizer contributing anything to the sound of the Ramones or Sex Pistols. In the end, though, synthesizer manufacturers didn’t need the punks because their instruments were quickly becoming the mainstay of an even more popular—and lucrative—genre called disco, particularly in tunes written and produced by Giorgio Moroder, such as the 1977 Donna Summer hit, I Feel Love.

Giorgio Moroder and Pete Bellotte used a Moog synthesizer to help make Donna Summer’s “I Feel Love” a 1977 disco hit.

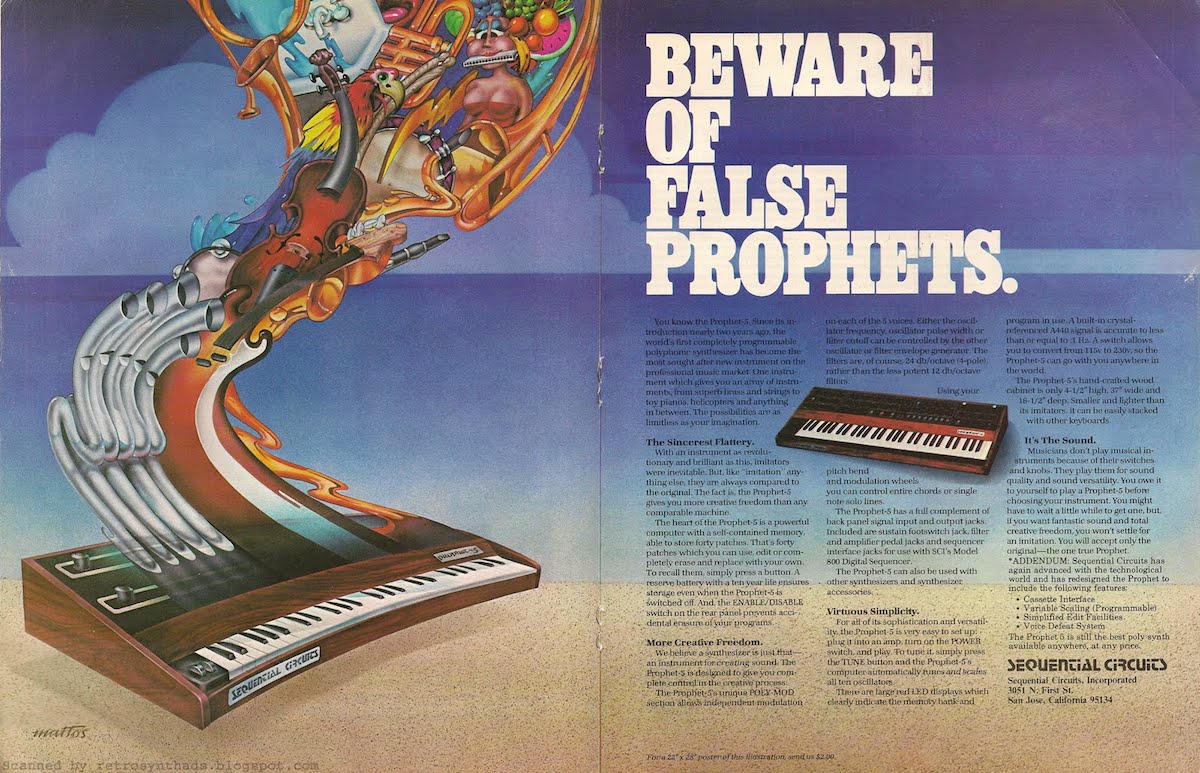

Smith stuck with synthesizers, which must have seemed like a pretty good call in 1978 when Sequential Circuits came out with the Prophet-5, the first polyphonic synthesizer, which meant it could play multiple notes (in this case, five) at the same time. Bob Moog may have blazed the trail in 1964 with his modular synthesizer, but Dave Smith had made the machine an instrument. Now chords were possible, as well as radioactive leads accompanied by molten bass lines

“The response was immediate,” Smith says. “Everybody loved the way it sounded, and there was nothing else like it. People all over the world were yelling at us to get one as quickly as possible.” Among the yellers were David Bowie, Rick Wakeman of Yes, and Joe Zawinul of Weather Report, each of whom snapped up one of the first handful of Prophet-5s manufactured. “Our biggest problem for the first couple of years was trying to build enough,” Smith adds. “We were a very tiny company when the Prophet-5 was announced. I think our backlog was a year.”

It wasn’t just the instrument’s polyphony that made the Prophet-5 so popular. Smith had been hearing the complaints about synthesizers going out of tune for years, so he made fixing this critical flaw one of his top priorities. “The original Minimoogs were horrible,” Smith says. “If you waited 10 minutes, you’d have to re-tune it. One of the main innovations of the Prophet-5 was to use its internal computer to re-tune the oscillators, which was even more important in a polyphonic system. So, when a musician walked out on stage, they just pressed the ‘Tune’ button, and the instrument would reset itself from the last time they had used it. Our newer products have made all that pretty much invisible,” he adds, “but back then this was a major innovation.”

A Prophet-5 (top) and T8 at Lance Hill’s Vintage Synthesizer Museum.

The late 1970s and early 1980s were golden years for synthesizers, spurring demand for instruments made by Oberheim and ARP in the United States, as well as Roland and Korg in Japan. In 1977, Devo’s first single, Mongoloid, featured a Minmoog at its beginning and end. Greg Hawkes made the Prophet-5-saturated Let’s Go a hit for The Cars in 1979, and he would use the same synth on Shake It Up in 1981. In 1980, Peter Howell of the BBC’s Radiophonic Workshop updated the theme of the Doctor Who television show with an ARP Odyssey. And in 1981, Geddy Lee used an Oberheim OB-X to create the rumbling glides that anchored Rush’s biggest hit of that year, Tom Sawyer.

By the early 1980s, you couldn’t turn on a radio or watch MTV without hearing the sound of a synthesizer. Nick Rhodes played a Prophet-5 for Duran Duran, as well as a Roland System 100, a Fairlight CMI, and a Memorymoog. Keyboardist Mick MacNeil’s OB-Xa, Roland Jupiter-8, and Korg 770 dominate just about every track on the 1982 breakthrough album for Simple Minds, “New Gold Dream (81–82–83–84).” And 1982 was also the year musician Stevie Wonder and inventor Ray Kurzweil teamed up to create a new line of Kurzweil synthesizers that used digital libraries of audio samples to produce their sounds.

An Oberheim OB-Xa (top) and Oberheim 4-Voice at the Vintage Synthesizer Museum.

Because they relied on audio samples rather than sounds that were designed from scratch, the Kurzweils were known as additive synthesizers. For the most part, though, subtractive synthesis still dominated the industry, and Oberheim and Sequential were the big dogs. Prince’s “1999,” for example, was recorded using both an OB-Xa and OB-SX. In 1983, Eddie Van Halen put down his electric guitar long enough to come up with a punchy pop-synth riff on his OB-Xa for Jump, resulting in yet another hit single for his eponymous band. That same year, Sequential Circuits also had its moments in the sun, as when Jerry Harrison of the Talking Heads played a Prophet-5 on Burning Down the House. The Prophet-5 also helped make Madonna’s Lucky Star the biggest hit of her debut album.

While clubbers in New York City were tearing up the dance floor at Danceteria to “Lucky Star” and Frankie Goes to Hollywood’s smash hit, “Relax,” for which keyboardist Andy Richards used a Fairlight CMI and a Roland Jupiter 8, a preteen from Tennessee named Lance Hill was also starting to get into synthesizers, but only inasmuch as he was listening to a lot of Van Halen and Duran Duran. “I can’t say that in the ’80s I was fixated on the technology at all,” Hill says. “It wasn’t until I wanted to make certain sounds for my own music that I got interested in synthesizers.”

For Hill, who now runs the Vintage Synthesizer Museum in Oakland, California, that transition began in the early 1990s, when he was around 18 and started doing his own home recording. “I was hanging out with musicians, constantly listening to, and talking about, music. I was listening to a lot of indie rock at the time, and whenever there would be these weird sounds, I was like, ‘Oh, that’s a Moog; that’s an Oberheim.’ Pretty quickly, I wanted to create those sounds in my own stuff.”

Lance Hill, goofing around with a pair or Roland synthesizers. The vintage guitars on the wall behind him are also used by artists who come to his studio to record

Except, of course, he couldn’t afford any of the machines that made these weird sounds. Fortunately, a friend’s dad had a Moog Rogue. “She lent it to me and my roommate for, like, six months. He was a cool guy—he probably didn’t even know we had it. We did a bunch of recording with it, which was an eye-opener. I didn’t know what I was doing, but if you took your time, it was easy to coax out sounds.”

Around 15 years ago, Hill moved to California, rented a room in another friend’s place in Berkeley, and tried to make it as a musician. Eventually, with his living expenses low and working two jobs, Hill started saving to buy a synthesizer of his own, which he did when he spotted a Yamaha CS-20M on Craigslist for a hundred bucks. The problem was, it didn’t work, but Hill had also found a repair guy in Berkeley who was “super cheap, amazingly good, and competent. Honestly, if it weren’t for him, I wouldn’t have a big collection of synthesizers today.” Another hundred bucks and a new power supply later, Hill had his first synthesizer.

Today, Hill’s collection includes a Yamaha CS-20M, but not that first one that he bought and had repaired. “I traded it to a friend for a different synthesizer,” he says of the strategy he’s used to feed his synth habit. Hill also has a Prophet-5, as well as a Sequential Circuits Pro-One, the company’s first mono synth from 1981, and a Prophet-T8, an eight-voice polyphonic synthesizer from 1983. Naturally, Hill has an Oberheim OB-Xa, as well as a pair of Roland Jupiters (an 8 and a 4), a Minimoog, and an ARP Odyssey. He’s also got an ARP 2600, an ARP Sequencer, a quartet of Korgs, an EMS Synthi AKS like the one Kraftwerk and Pink Floyd used, and a few bona-fide museum pieces, including a rare Gleeman Pentaphonic from 1982, prized for its clear Plexiglass case.

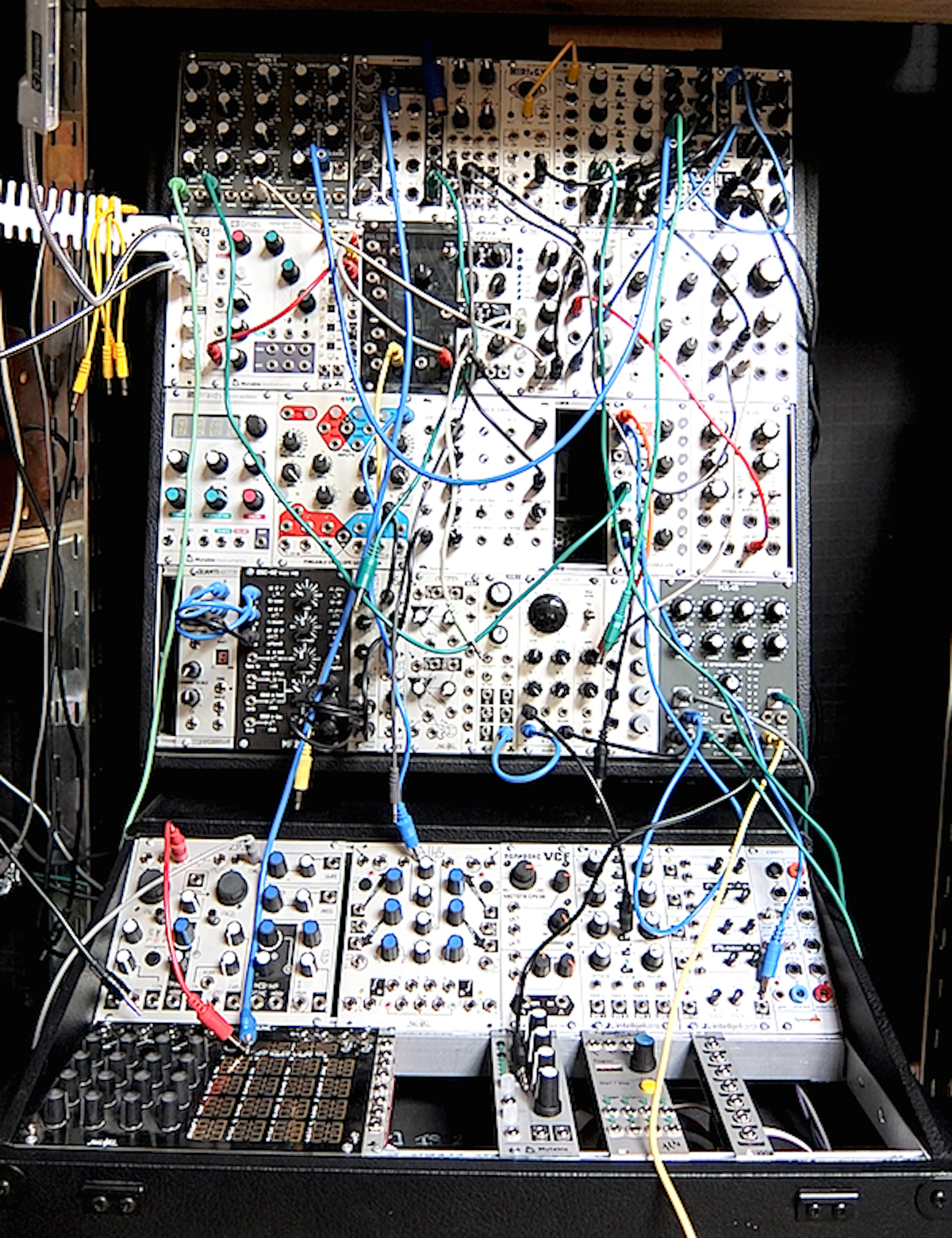

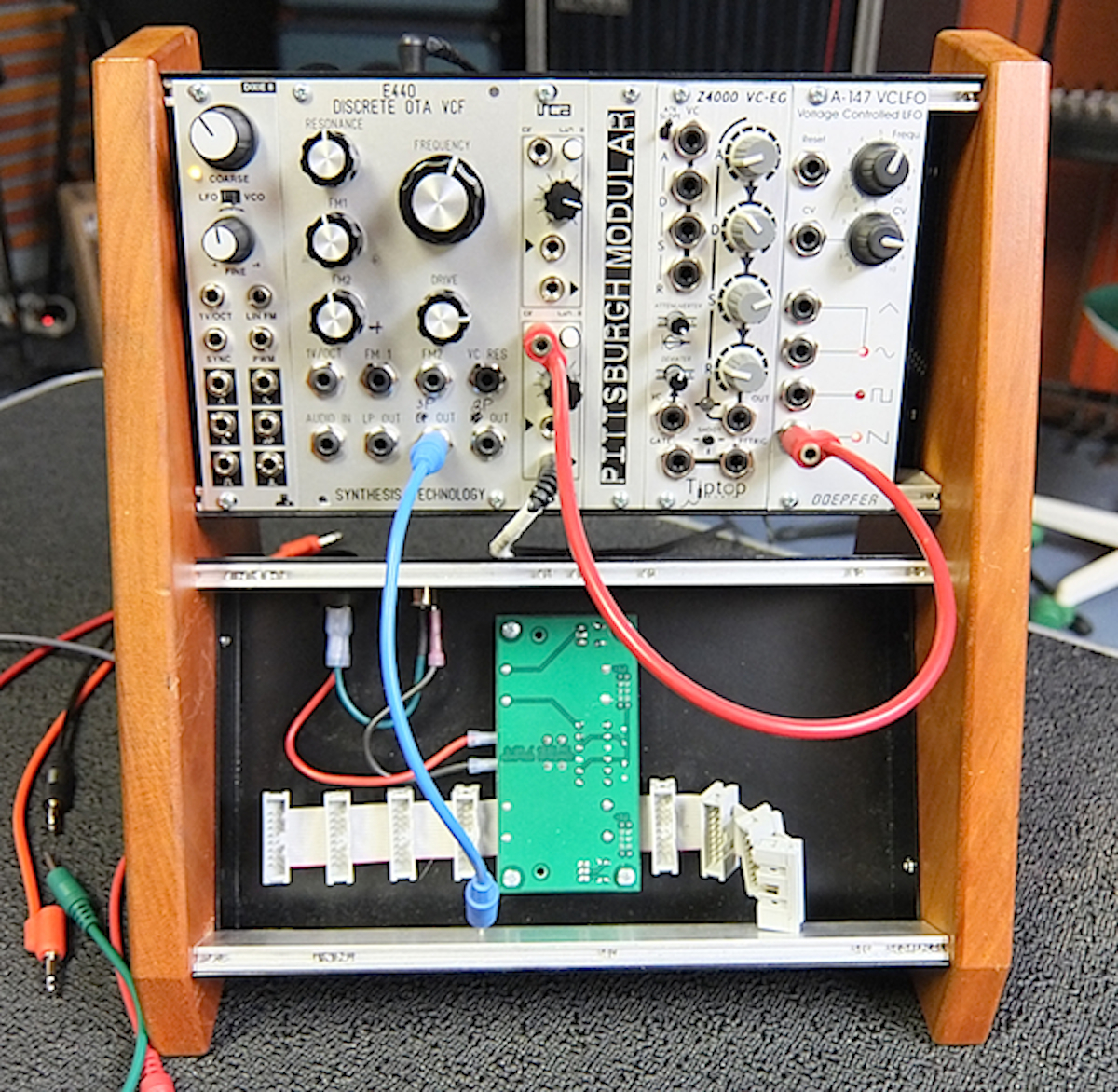

A modular Eurorack synthesizer at Vintage Synthesizer Museum.

And then there are Hill’s collection of newer, so-called Eurorack modular synths, which are scattered about the studio seemingly at random, their faces bursting with colorful patch cords. Unlike the Prophets, Oberheims, Rolands, and Korgs that actually look like instruments, Euroracks look like machines, designed less for their aesthetics onstage than their ability to goose sounds from unsuspecting electrons.

On a recent visit to the Vintage Synthesizer Museum, Hill sits me down in front of one of his Euroracks, a small case the size of a bedside bookshelf that’s made by a company called Pittsburgh Modular. On the top row of the rack are five modules—a six-waveform oscillator called the Dixie II made by Intellijel, an E440 filter made by Synthesis Technology, a Malekko Heavy Industry amplifier, a Tiptop Audio envelope generator, and a Doepfer A-147 low-frequency oscillator with four waveforms. Hill has verbally explained how synthesizers work. Now it’s time for a demonstration.

“This is a basic synthesizer voice,” Hill says of the five modules. “This is the oscillator module,” he says, pointing to the Dixie II. “That’s what’s going to make the sound. When you set up a circuit to make the electrons arrange themselves in a shape like a triangle, sawtooth, or square, those shapes remain constant and repeat. Because it’s constant, if you speed it up, we perceive the result as a rise in pitch. If you slow it down, we perceive that as a lower pitch. You can adjust it right out of the hearing range, in either direction, of course.”

Hill used this smaller Eurorack setup to demonstrate how to build a sound on a synthesizer.

Of course. Hill plugs one end of a patch cord into the sawtooth receptacle of the Dixie II and then plugs the other end into the amplifier and slowly turns a potentiometer—what you and I would call a “knob.” “This is what’s making the sound,” he says, pointing to the end of the patch cord that’s plugged into the Dixie II. “We’ve just created a circuit to make the electrons travel in a certain way repetitively.”

The machine hums. “This is the amplifier,” he says, “which doesn’t really amplify anything. It’s just attenuating.” In other words, the amplifier is actually reducing the voltage of the signal coming into it, which seems like the opposite of amplifying to me, but never mind. “I’m going to try to adjust the input into the amp.” Hill says as he turns another knob back on the Dixie II. Instantly the studio fills with sound. “It’s a little dull,” he yells over the steady tone, “because I’m not driving it that much. But we’ve got this amplifier crazy loud.”

As Hill turns the knob on the Malekko VCA to the left, the sound ceases, and then he plugs in another patch cord. “You can also send the audio through this filter,” he says, “which is kind of like an equalizer.” Next he plugs a cord into something called a low-pass filter. “Now it’s just letting the low frequencies pass, so what you’re doing is cutting out the high frequencies, the higher harmonics. At this point, we can add another control called ‘resonance,’ which is a very common option on most voltage-controlled filters. That’s going to produce way more articulation of the sound, like you’d hear in a wah-wah pedal.

This EMS Synthi AKS at the Vintage Synthesizer Museum is just like the one Pink Floyd used on “Dark Side of the Moon.”

“So, this is the audio signal path of a synth voice,” Hill concludes. “You’ve got the sound source, the oscillator; a sound modifier, the filter; and another sound modifier, the VCA, where you can control amplitude, or volume. That’s the basic audio path, and this is why it’s called subtractive synthesis. You start with a rich tone and remove harmonics and amplitude. That’s how you shape a sound from scratch.”

The entire process of charting an audio path to shape a sound is somewhat like adjusting a string to tune a guitar, although tuning a synthesizer is light-years trickier. In addition, synthesizers can be every bit as finicky as stringed instruments when it comes to their repair—they are not merely collections of interchangeable parts, as Hill has seen firsthand.

“A friend of mine has an EMS Synthi,” Hills says. “I have one, too. He’s from England, where EMS is located, and when he went home to visit his family, he brought his Synthi with him and took it to the EMS guys to have it refurbished. It sounds much brighter now with its newer, high-efficiency components that weren’t available in the ’60s, but you couldn’t pay me to take his over mine. Mine sounds so much better. It sounds like the ’60s.”

Whose synthesizer sounds best is actually something Dave Smith didn’t spend a whole lot of time thinking about when he was running Sequential Circuits in the 1970s and early ’80s.

When the Prophet-5 was released in 1978, it was the only polyphonic synthesizer on the market, but by 1980, the marketing department at Sequential felt the need to run this ad. Courtesy Retro Synth Ads.

“When the Prophet-5 came out, we had no direct competitors,” Smith says. “That was the whole thing about the Prophet-5—it was the first instrument to put everything together the way most musicians wanted. So there was no competition until other companies were able to react a year or two later, coming up with their own spins on the same concept. Oberheim was probably the first, followed by Roland, Yamaha, and Korg. Within three or four years, there were at least six or seven companies making polyphonic analog synths.”

Still, for Dave Smith, people like Tom Oberheim and Alan R. Pearlman (his initials are the A, R, and P in ARP) were also colleagues. “Basically, we were all friends with each other. It was a small industry. Everybody knew everybody. Not that many people in the world were doing this, so we would be fierce competitors on one level, but at the same time, at the trade shows, we’d get together to have a drink, talk, and hang out.”

Eddie Van Halen, playing the Oberheim synthesizer part on the video for “Jump.”

That collegial attitude helps explain why Smith wasn’t especially jealous when he heard “Jump” by Van Halen or “1999” by Prince and knew those hits had been made on an Oberheim. “Did the guy who designed the Telecaster get mad if he heard somebody playing a Les Paul?” Smith asks. “I don’t think so. Musicians have their preferences when it comes to sound, and there are just as many Prophet-5 musical trademarks out there on records as there are Oberheim, probably more. Nobody gets to have a hundred percent of the market.”

That said, Sequential’s share was substantial. “The Prophet-5 is all over Pink Floyd’s The Wall. Atomic Dog by Parliament is like a Prophet-5 commercial. Genesis, Peter Gabriel, Phil Collins, Talking Heads: There was a period when almost every week on Saturday Night Live, somebody on there would be playing a Prophet-5. Everybody used it.”

Occasionally, Smith admits, musicians took the Prophet-5 to completely unexpected places. “Brian Eno is the first person I know of who played the Prophet-5 by rapidly running his fingers across the program select buttons and actually play the synth by changing programs as opposed to hitting keys. That was something nobody had thought of. When you build an instrument, you have ideas about how you think musicians will use it and the sounds they’ll make. Then, somebody comes along and does something totally different. That’s the fun part.”

In 2013, Dave Smith, seen here near his company’s San Francisco headquarters, was awarded a Grammy for developing MIDI with Ikutaro Kakehashi of Roland. Kakehashi won an award, too.

By the 1980s, Smith was a leader in his industry, in part because of the quality of his instruments but also because of his commitment to scene as a whole. In 1981, Smith laid the groundwork for what would become the Musical Instrument Digital Interface, more commonly known as MIDI, which allowed synthesizers to predictably communicate with each other and, increasingly importantly, computers. Incredibly, the MIDI protocol that Smith eventually developed with Ikutaro Kakehashi of Roland has remained unimproved since 1982—it is still in version 1.0. A few years ago, in 2013, Smith and Kakehashi each won a Technical Grammy Award for their pioneering work.

Unfortunately, Smith’s prominence in his industry could not staunch the tidal wave of less-expensive synthesizers that filled musical-equipment stores in the mid-1980s. Nor was it simply a matter of price-consciousness—by 1985, when Magne Furuholmen of the band A-ha sat down in front of a synthesizer to pound out the catchy riffs of the MTV hit “Take on Me,” his synth of choice was a Roland Juno-60 (although for some reason a Prophet-5 was used in the MTV video). The synthesizer wasn’t dying, but the American synthesizer industry definitely was. Within a few years, Japanese manufacturers such as Roland, Yamaha, and Korg were clobbering Oberheim, Sequential Circuits, and ARP. The sounds of synthesizers were more popular than ever, but the U.S. manufacturers that were once at the leading edge of synthesizer technology were toast.

“Back in the 1980s, people were worried the Japanese were going to take over the world because they were doing everything right,” remembers Smith. “It was easier, in a lot of ways, to manufacture in Japan than it was in the United States. It was just a completely different situation over there.”

One of the gems of the Vintage Synthesizer Museum is a rare, clear, Gleeman Pentaphonic. Below that is a recent reissue of an Electric Music Box, often called a Music Easel, manufactured by Buchla. The Sequential Pro-One to the left is also fairly common.

In 1987, Smith had to sell Sequential Circuits to Yamaha, and for a while, he ran a California-based research-and-development group for Japanese manufacturer Korg, which resulted in the popular line of Wavestation synthesizers in 1990. But since 2002, around the same time that Lance Hill was beginning to amass his collection, Smith has been making synthesizers of his own design, along with a drum machine called the Tempest co-designed by Roger Linn, in the United States under the name Dave Smith Instruments. Then, earlier this year, at the urging of his longtime friend and MIDI collaborator Ikutaro Kakehashi, Yamaha decided to give Smith his Sequential brand back, apparently because it was just the totally righteous thing to do.

Today, a contractor located in an industrial area just south of San Francisco manufactures all of Sequential’s electronic instruments. “This time around, we’re much smaller,” Smith says of the 2015 incarnation of Sequential, which is now a high-end boutique instrument-maker rather than a company aiming for the mass market. “There are only 12 of us—the original Sequential had 170. It’s all about keeping the company alive forever and making it profitable rather than taking over the world. Still,” he adds somewhat proudly, “we’ve sold more Prophet ’08s than we sold Prophet-5s.”

That’s probably because of their storied reputation, but it also has to do with the way Prophets sound. And who plays Prophets today? “People you would expect,” Smith says, “like Radiohead, Arcade Fire, and a lot of smaller groups, but Taylor Swift also plays one of our keyboards in concert, as does Alicia Keys. They’re showing up everywhere.”

Patch chords at the ready in the Vintage Synthesizer Museum.

MOOG Synthesizer pioneer, Robert “Bob” Moog, holds a new Moogfooger synthesizer as he sits next to a 1971-era Minimoog synthesizer in his Asheville, N.C.. office, . Moog has been making and playing synthesizers for more than three decades

Some of Sequential’s latest synths are analog while others are digital or hybrids of the two. And for what it’s worth, that’s just fine with Lance Hill of the Vintage Synthesizer Museum. After all, he’s always believed that playing an instrument that delivers the sound you are searching for is more important than fealty to this or that technology.

“If I’m making music, I’ll use analog, digital, whatever. It doesn’t matter to me,” Hill says. “This place has no agenda,” he adds, looking around his studio. “Digital synths are cool, computer software is cool, too. Anything that makes a sound that helps people create is great. The goal is to blow people’s minds.” You know, like Keith Emerson did in only one take way back in 1970.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.