Radical movements often espouse the most conservative of values. Dada claimed it was radical, anti-bourgeoise, and anti-capitalist in its aesthetics. But two of its key members (George Grosz and John Heartfield) refused to include any women (or their work) in the movement. Women, they said, were there to make the sandwiches, pour the beer, and give credibility to the men’s sexual attractiveness, while they discussed ideas about art and how to change the world.

Hannah Höch was a woman and she knew how to change the world. But few of the Dadaists were listening. She refused to give in to Mama’s boys Heartfield and Grosz. By her talent and a sheer force of will, Höch became the only female member of the Dada movement. Heartfield and Grosz squealed objections and stamped their tiny trotters over Höch joining their little boys’ club. They claimed they supported women’s rights and equality and all that, but in reality they loathed the idea of a (any) woman being included in their gang.

So much for radicalism. But then again, equality between the sexes should not be a radical proposition. But sadly it is. And surprisingly, still is today.

Hannah Höch had dealt with this kind schoolboy sexism all her life. She was born Anna Therese Johanne Höch into a respectable, privileged middle-class family in Gotha, on the 1st of November, 1889. From her earliest years, Höch exhibited considerable promise as an artist. But her father fretted over such a possibility. He told her women were not meant to be artists, but were only meant (by the good Lord above) to be mothers and care-givers—“a girl should get married and forget about studying art,” he often told her.

As the eldest of five children, Höch was made look after her younger siblings. Be a mother, that is what you will be. At fifteen, Höch was pulled from school (Education is bad, my dear, you need only know how to care for children and keep a husband happy) to help look after her brothers and sisters. Her dreams of becoming an artist were sidelined until 1912 when she decided to make a stand, follow her dream, and enrolled at the School of Applied Arts in Berlin to study glass and ceramic design.

But fate is fickle friend, and the First World War soon cancelled her studies.

Höch joined the Red Cross. But her ambitions to be an artist proved too great for her to deny. She returned to Berlin and studied graphic art at the School of the Royal Museum of Applied Arts. It was here she met the Dadaists Raoul Hausmann (with whom she had a relationship) and Kurt Schwitters (who is said to have added an “H” to her name so it became a palindrome).

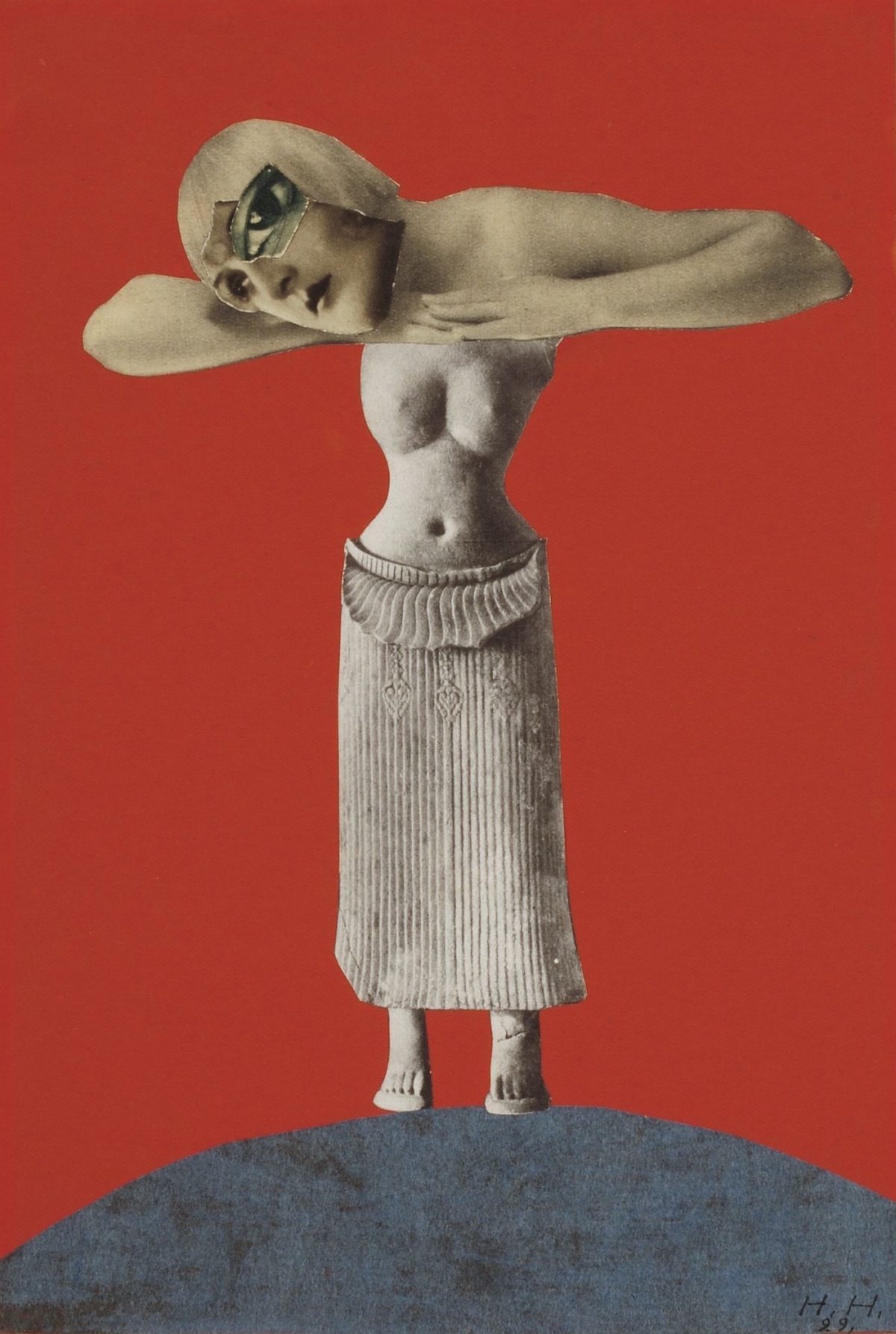

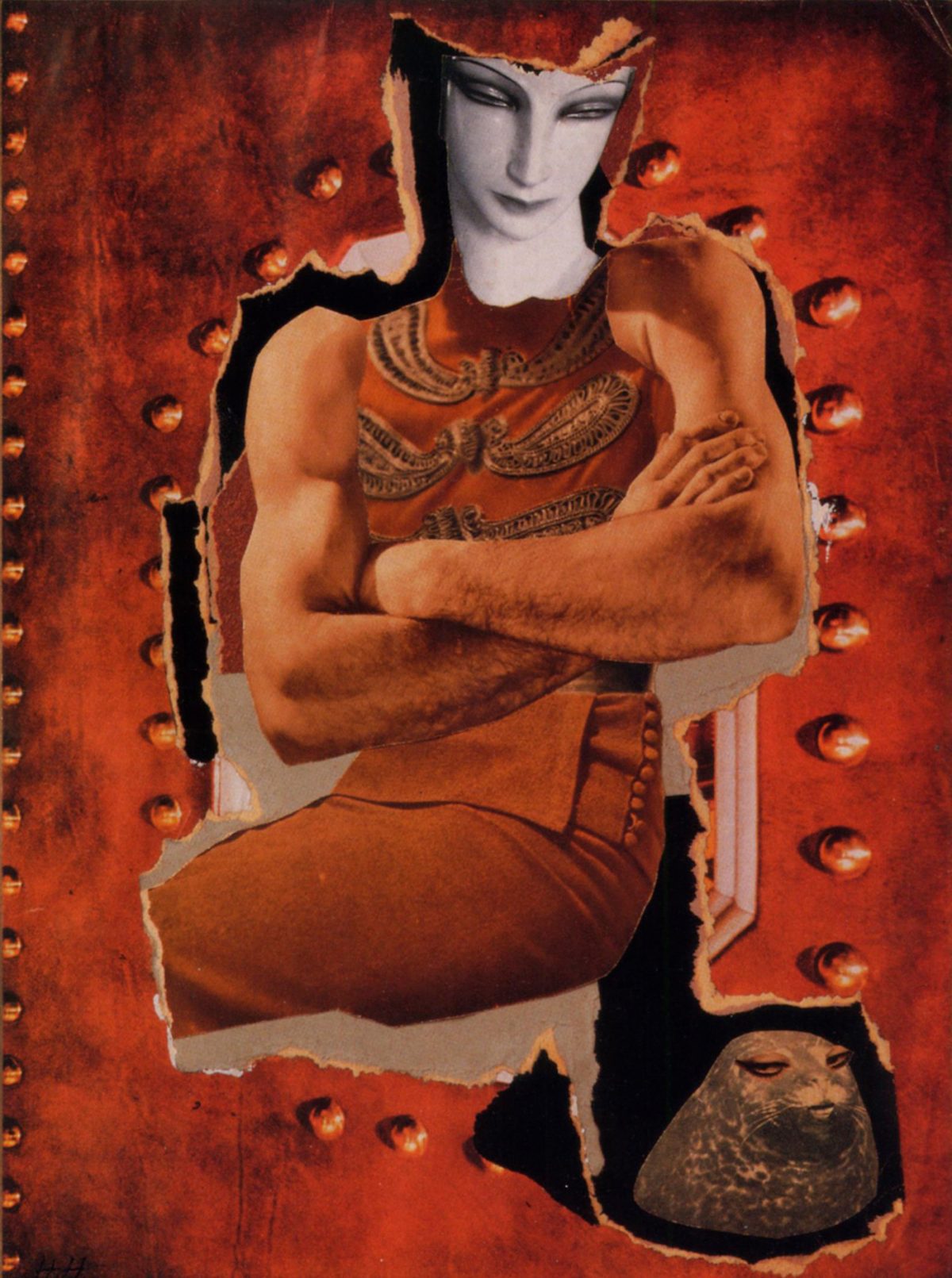

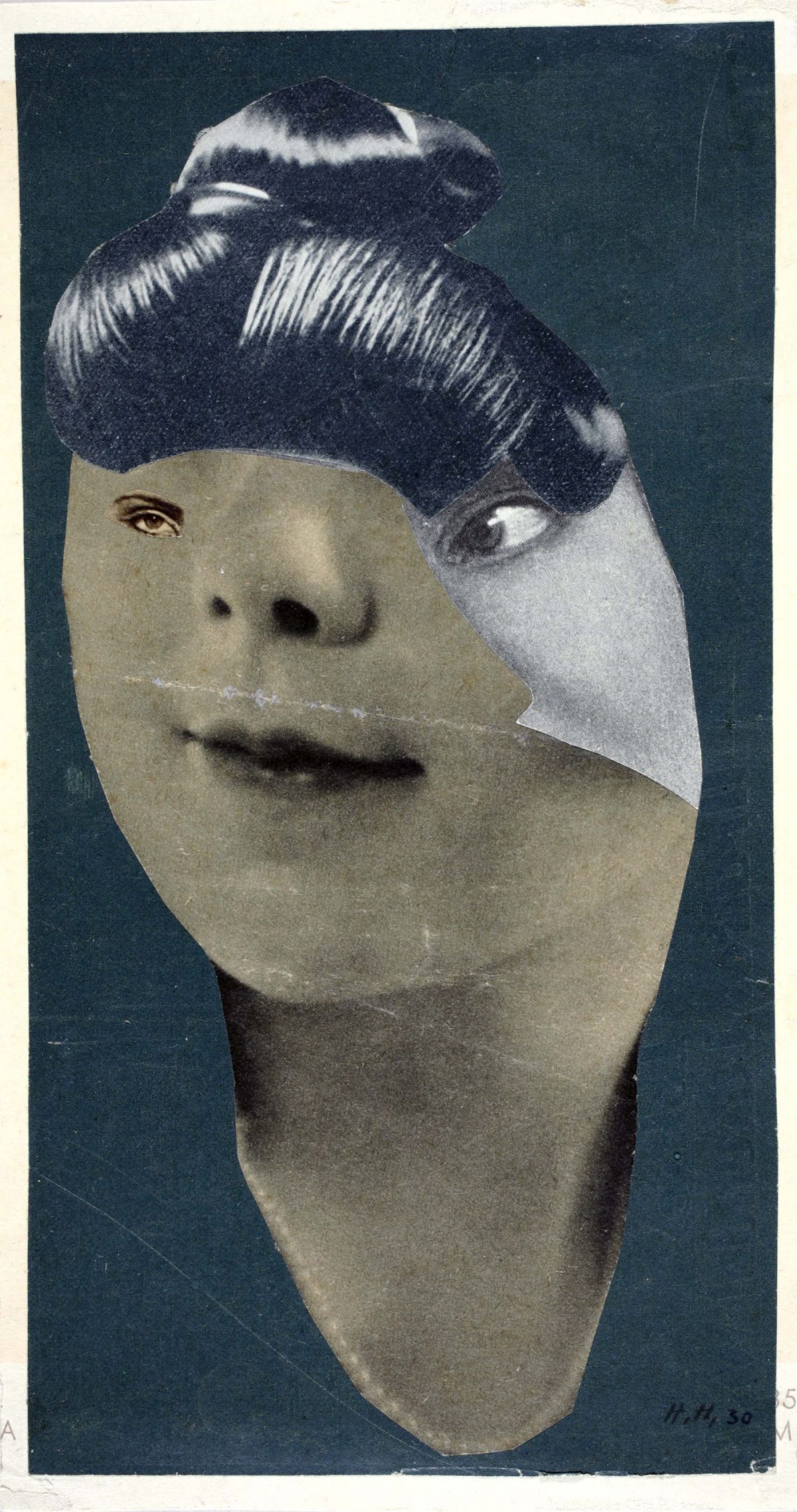

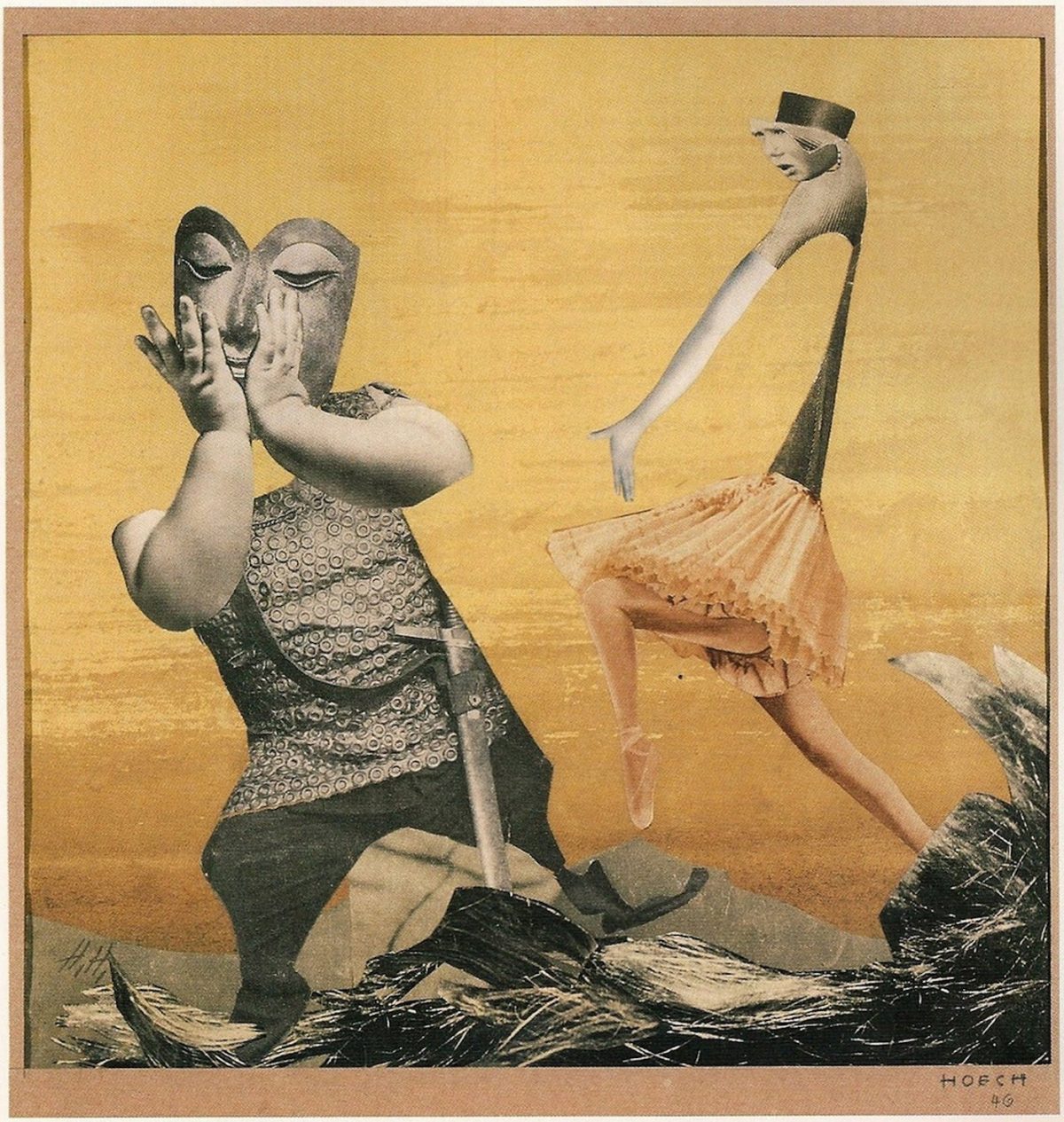

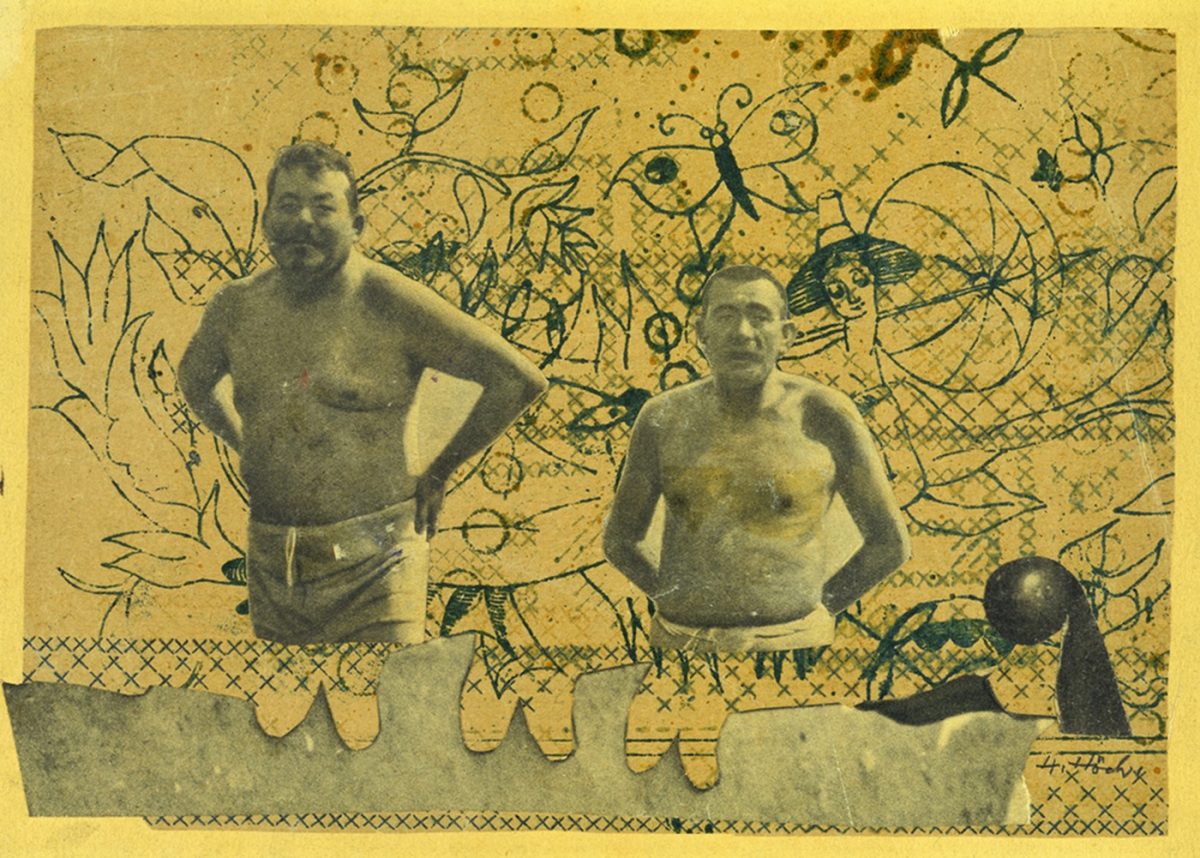

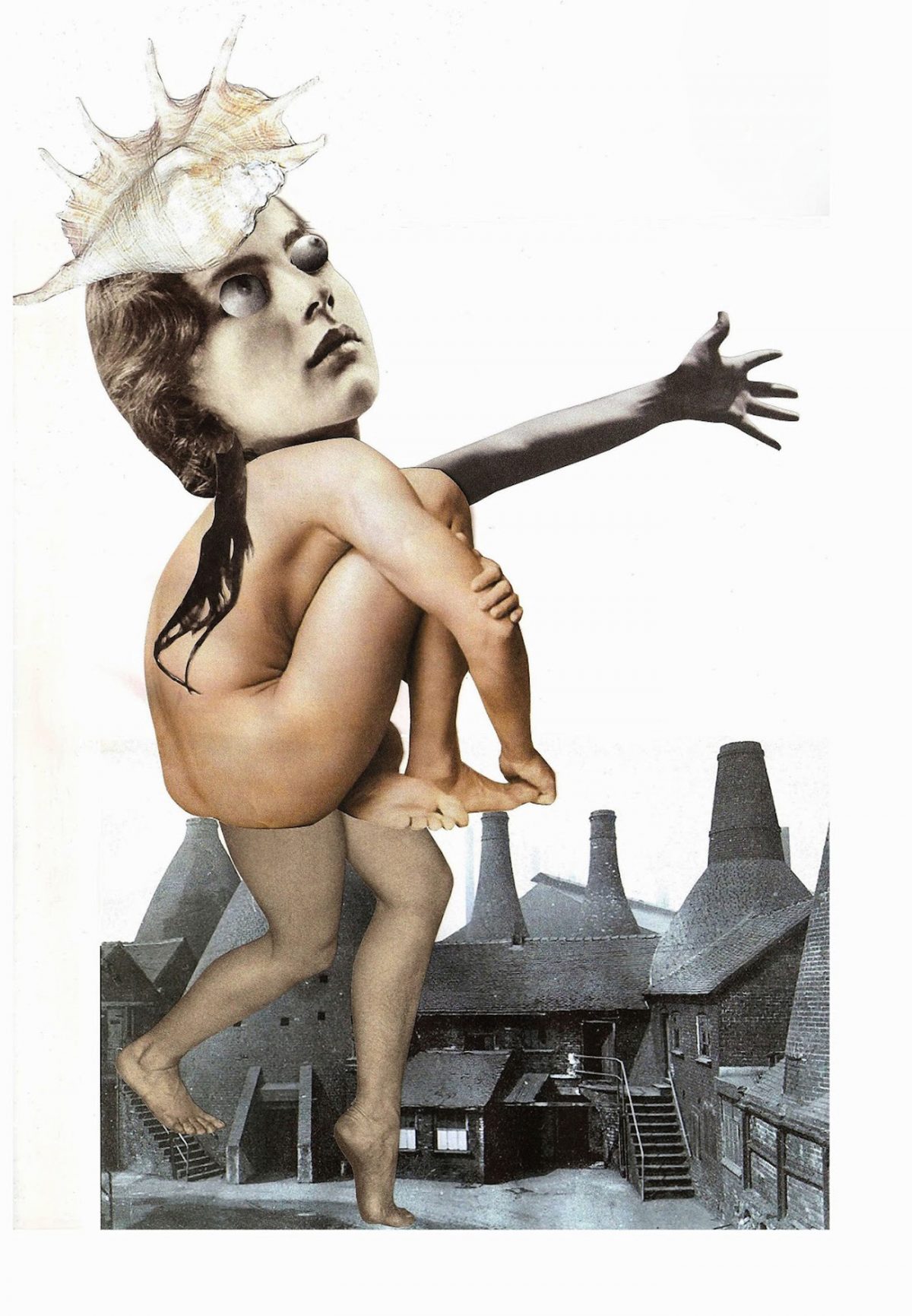

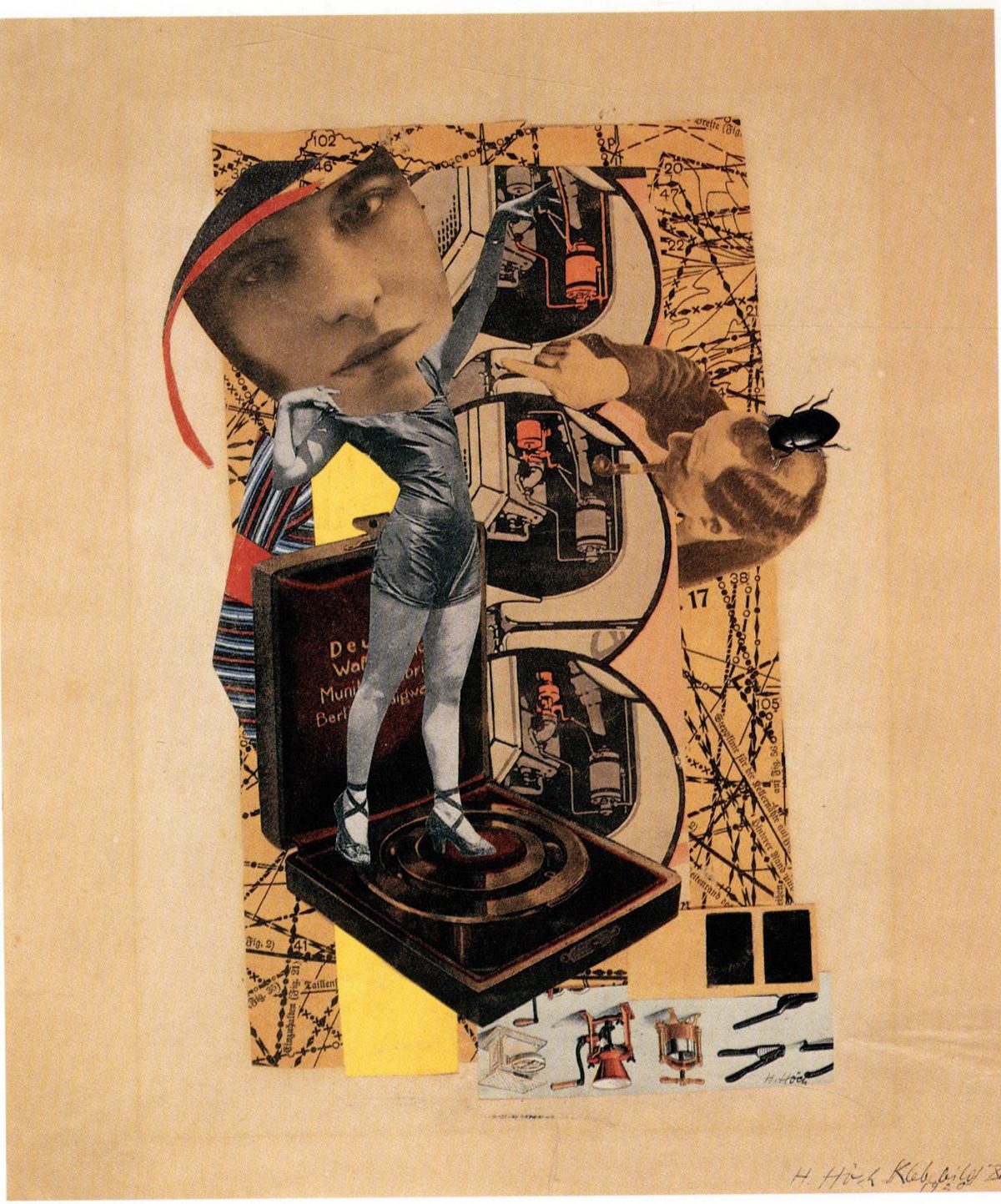

Encouraged by her new friends and at last seemingly in control of her life, Höch started making collages. Her inspiration came from the postcards German soldiers sent to loved ones where they pasted clipped photographs of their faces on top of the postcards’ images of cavaliers or peasants.

Höch then worked for a variety of magazines writing articles on handicraft and embroidery. She worked because her lover the weak, self-important Hausmann said it was her duty to support him because he was the real artist.

Höch later described her relationship with Hausmann in the short story “The Painter,” in which a male artist is filled with bitter resentment when he is asked by his wife (“at least four times in four years”) to wash the dishes.

Men are the weaker sex only their creative invention keeps them relevant.

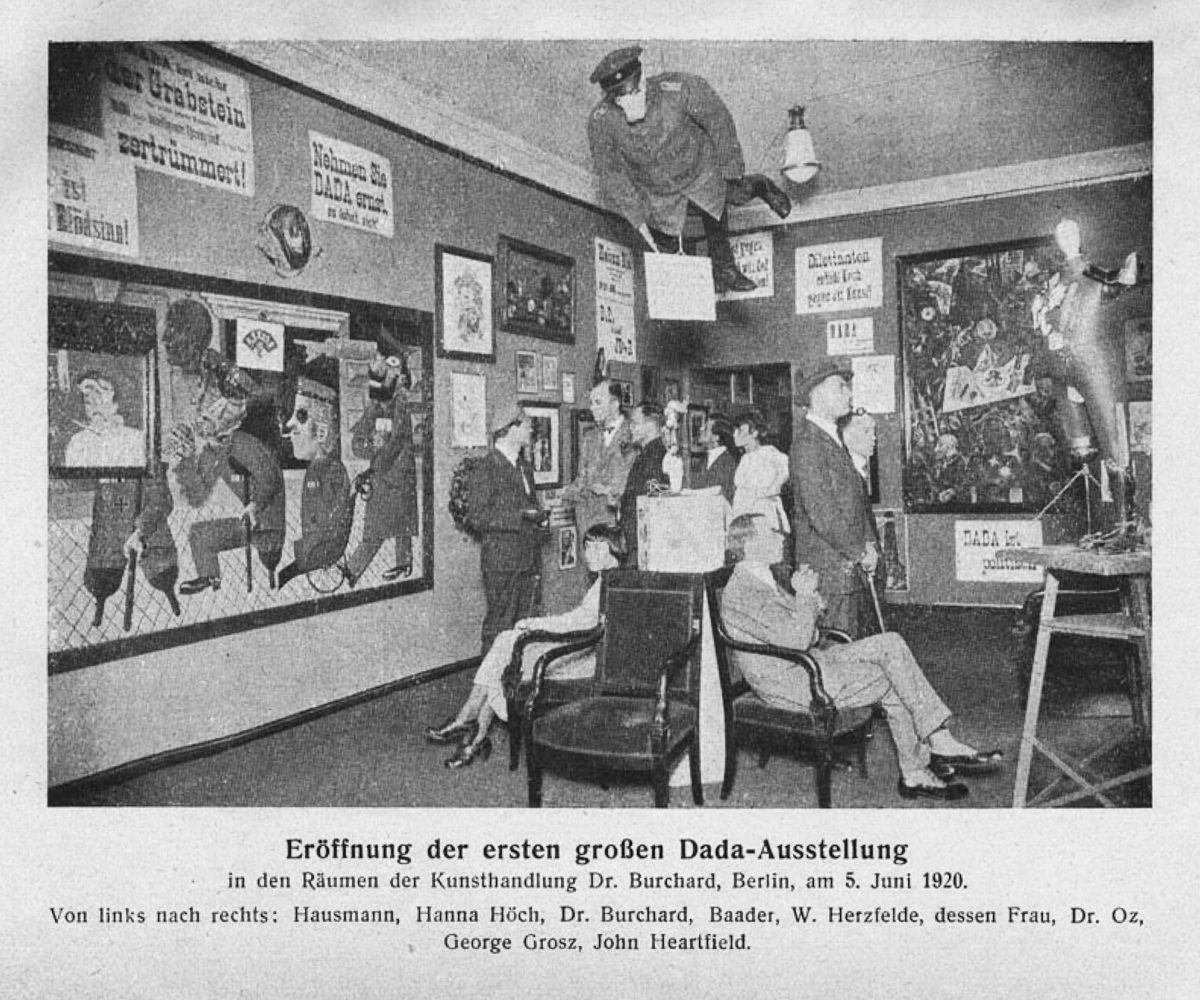

In 1920, Höch’s work was included in the First International Fair in Berlin. Grosz and Heartfield denounced her inclusion on the grounds that she was a woman. It was only when Hausmann threatened to withdraw his own work if Höch was not included that Grosz and Heartfield reluctantly relented.

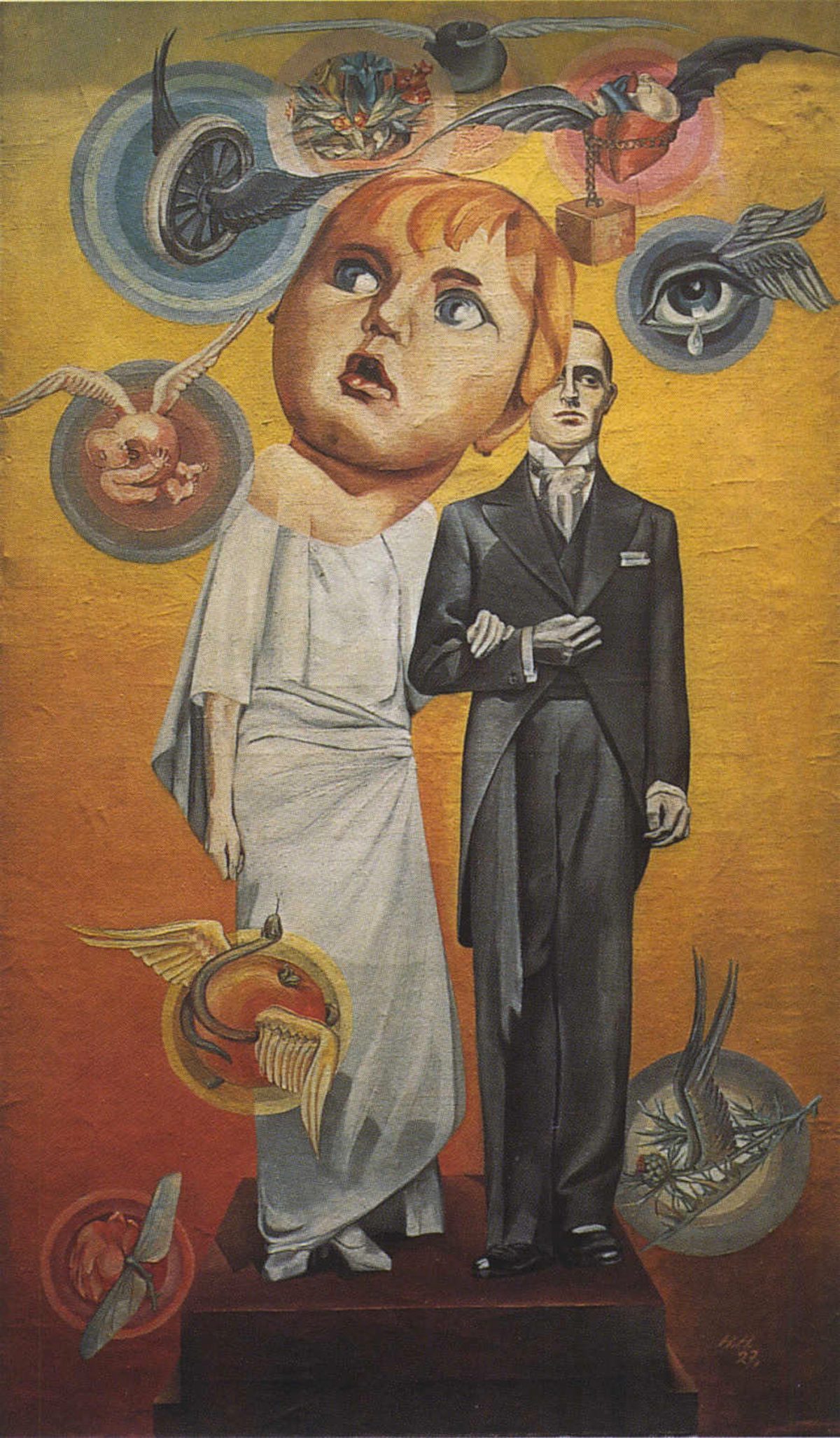

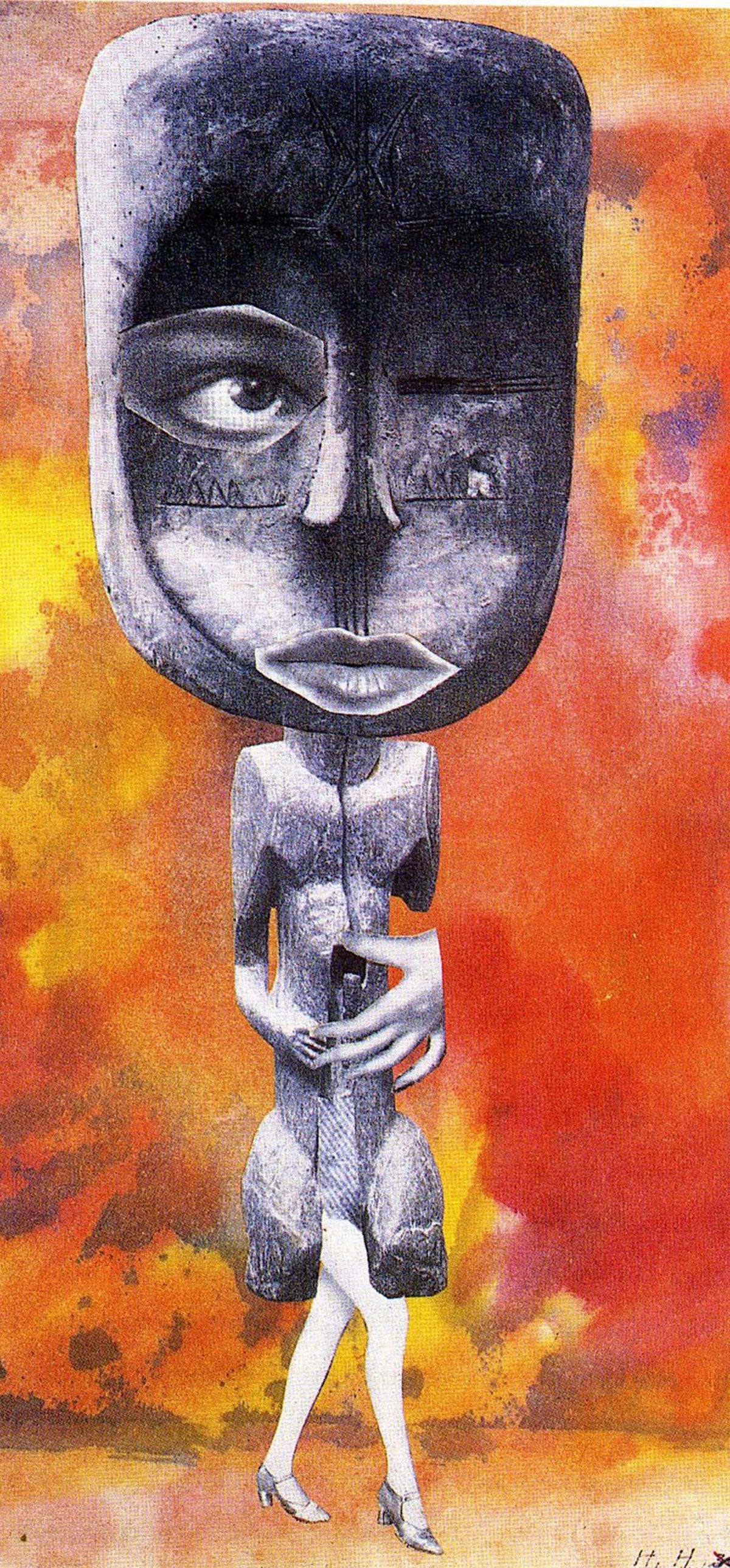

Yet, truth be told, Höch disliked the loud, boisterous, braggart exhibitionism of her fellow Dadaists. She thought them childish, silly, and embarrassing. While their work was primarily intended to shock and cause outrage, Höch was more interested in gender, sexism, identity, ethnicity, and society’s divisive inequalities. She explained how she used photographs as a painter uses color or a poet words.

In 1922, she Hausmann and began to move away from the Dada group. She commenced a relationship with the lesbian poet and writer Til Brugman, which lasted for ten years before she met and married businessman Kurt Matthies in 1938.

Grand opening of the first Dada exhibition, Berlin, 5 June 1920

She spent the Second World War hidden in plain sight living an almost anonymous life in a small cottage with its overgrown garden where she continued to quietly work. In 1944, she divorced Matthies.

After the war, Höch’s work moved towards abstraction with an interest in nature and the environment. Though her work from this time until her death is not as well-known, Höch was still highly prolific and controversial. She considered it the artist’s role to question accepted values and push for a better more equal society.

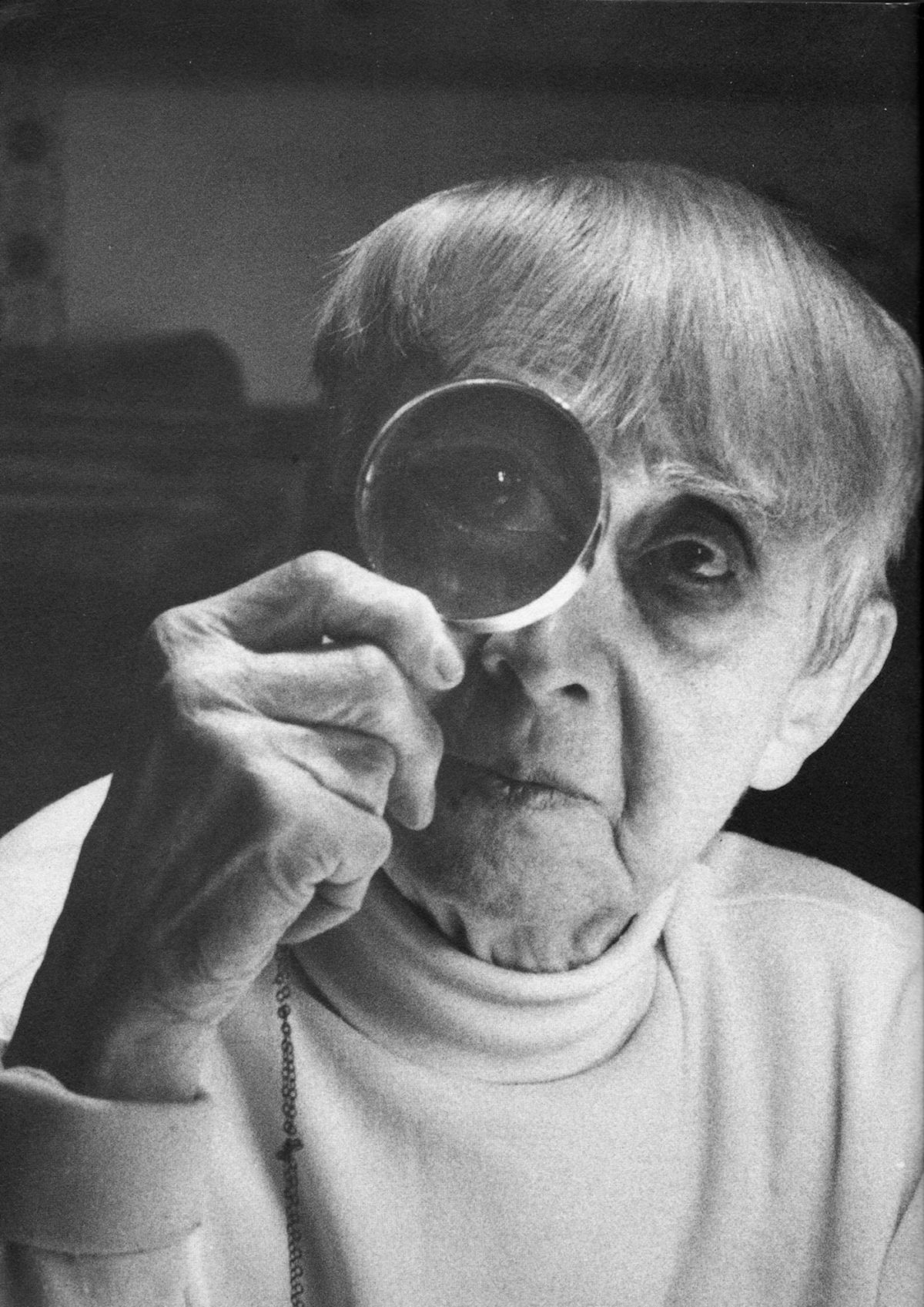

Höch never once lost her desire “to show the world today as an ant sees it and tomorrow as the moon sees it.”

She died on the 31st of May 1978, at the age of 88.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.