Like most civil rights movements in the U.S., the gay rights movement began much earlier than popular histories tell us, dating at least as far back the early 1950s with the founding of the Mattachine Society. Named after medieval bards who wandered around challenging injustices, the society had some impressive early success, then fractured over questions of anti-communism. Remaining conservative members stressed middle-class respectability and keeping a low profile. Their small protests observed a strict dress code and discouraged physical contact between attendees of the same sex.

All of this would radically change with the events usually credited with bringing about the LGBTQ movements that fill city streets around the world in Pride parades each year. The Stonewall riots “caused a split within the constellation of activists advocating for civil rights for gay people,” writes Rebecca Onion at Slate. “Gradualists—led by the old-guard Mattachine Society (founded in 1950)—denounced the violence of the riots and sought to work within the legal system to bring about change. Many younger gay people and allies thought more radical protests were necessary.”

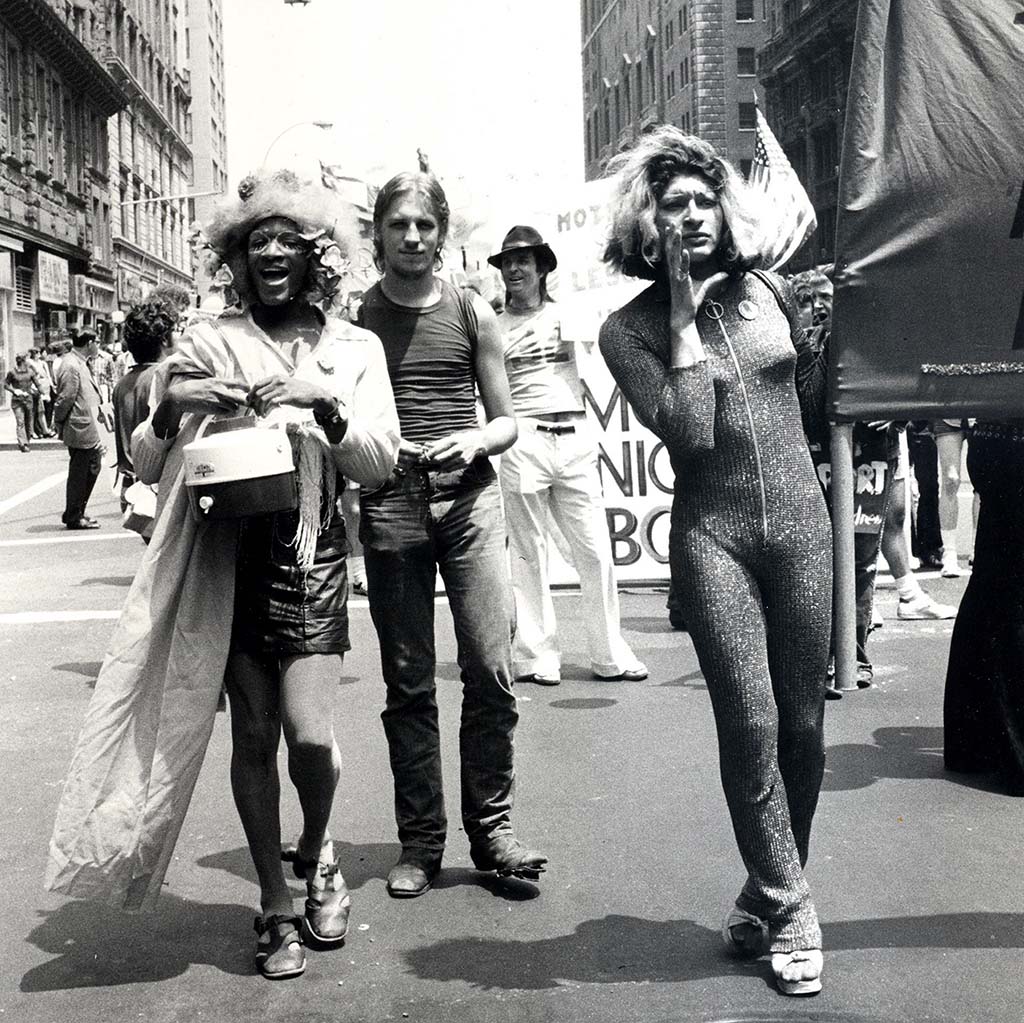

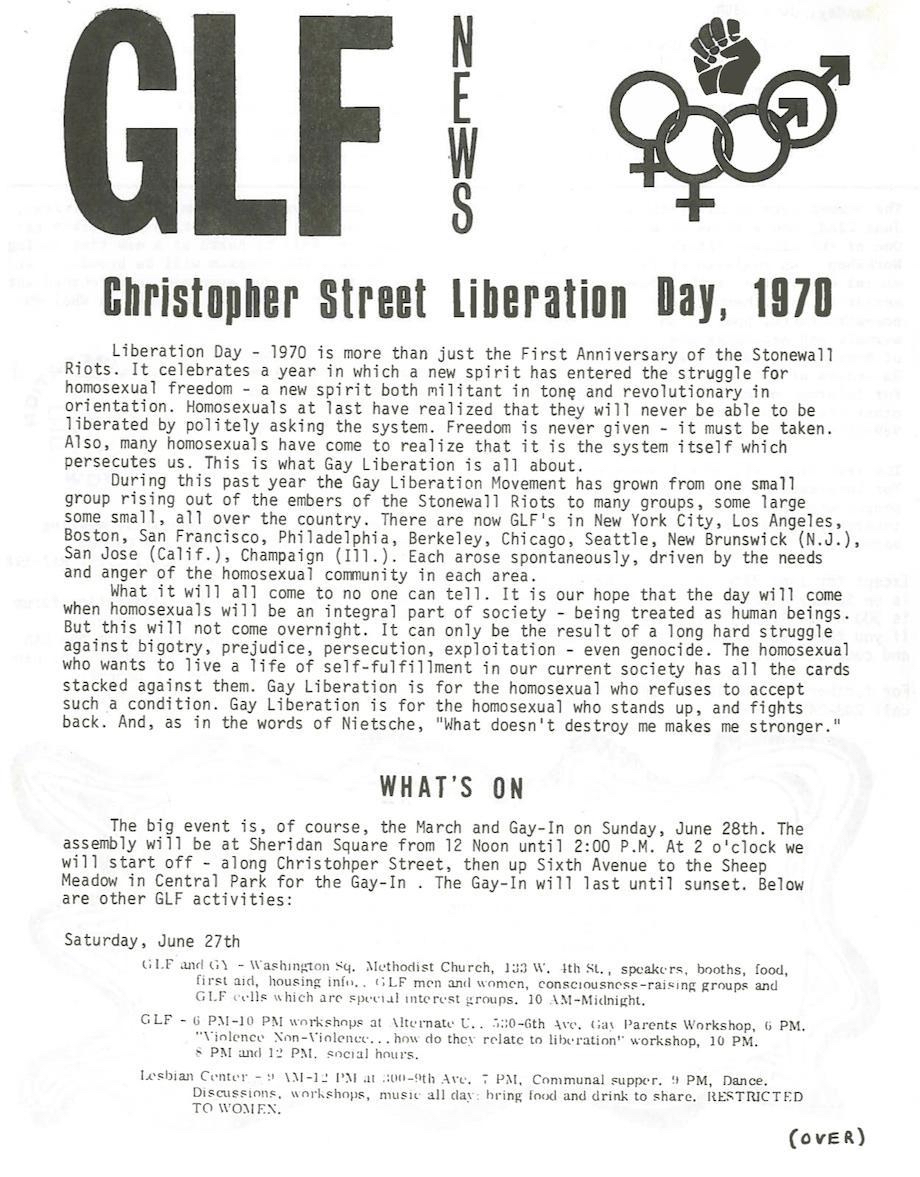

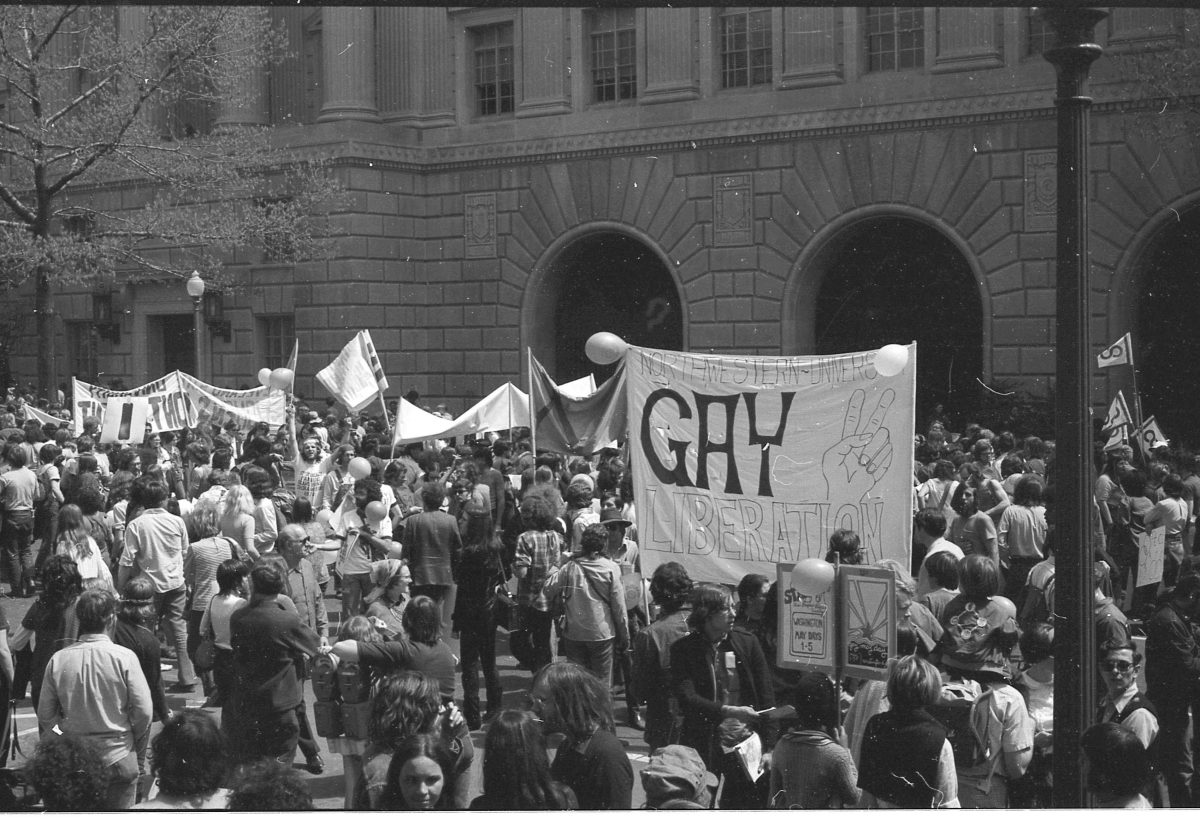

Led by activists like drag performer and early trans icon Marsha P. Johnson (above, left), the new generation fully embraced the radical tactics of the movements of the sixties. The Gay Liberation Front included an upraised fist in its symbolism and helped organize the first Pride march in New York in 1970. The flyer for what was called the Christopher Street Liberation Day march, held on the first anniversary of Stonewall, reflected the new movement’s militancy: “Homosexuals at last have realized that they will never be able to be liberated by politely asking the system. Freedom is never given—it must be taken.”

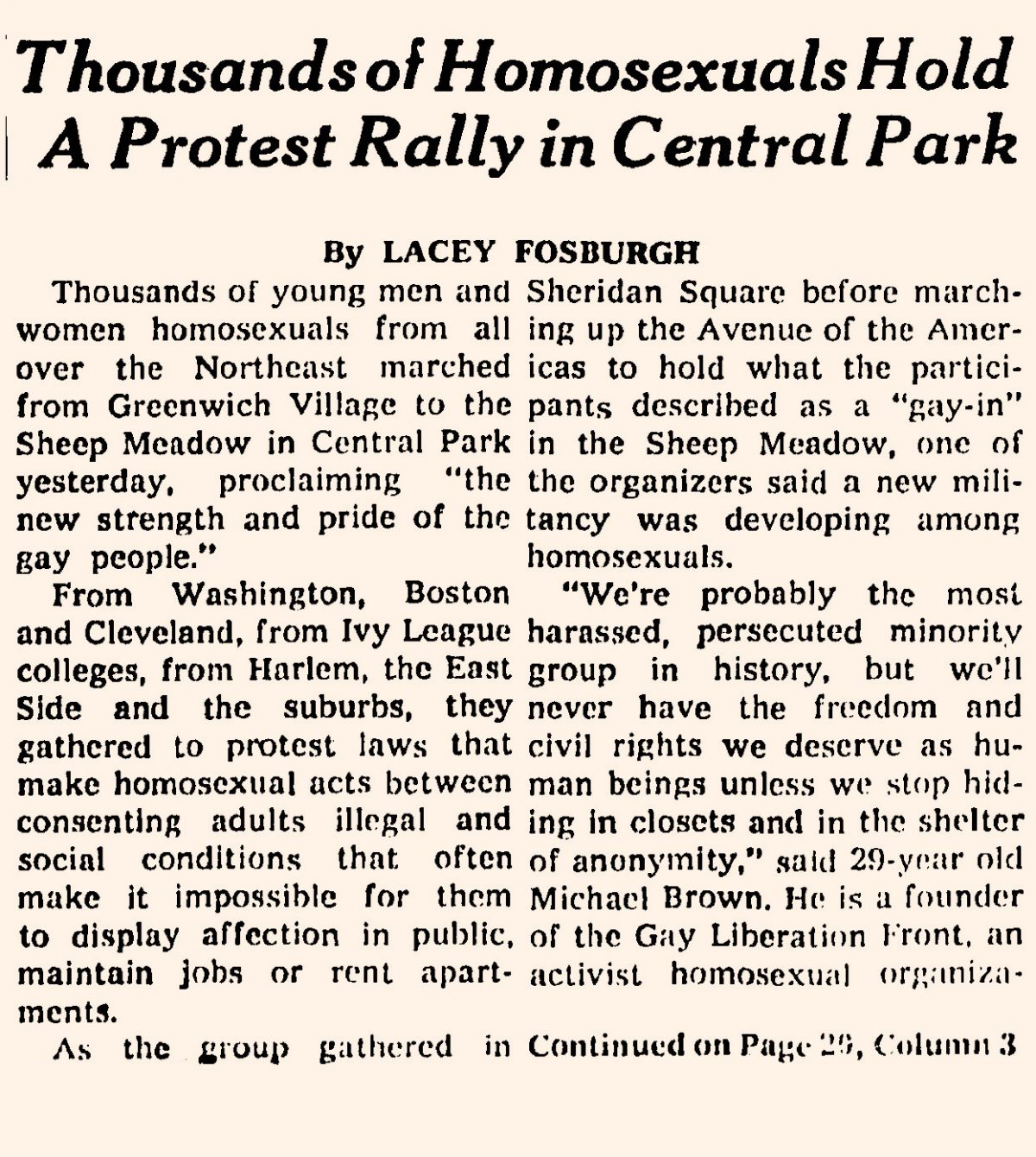

Liberation could only come about, GLF wrote, as “the result of a long hard struggle against bigotry, prejudice, persecution, exploitation—even genocide. Gay Liberation is for the homosexual who stands up, and fights back.” Thousands responded to the call, at first tentatively, then with more confidence as the parade wove through the streets on June 28, first gathering west of Sixth Avenue at Waverly Place then marching to Central Park for a celebratory post-parade “Gay-in.” One eyewitness and organizer remembers the day well:

Back then, it took a new sense of audacity and courage to take that giant step into the streets of Midtown Manhattan. One by one, we encouraged people to join the assembly. Finally, we began to move up Sixth Avenue. I stayed at the head of the march the entire way, and at one point, I climbed onto the base of a light pole and looked back. I was astonished; we stretched out as far as I could see, thousands of us. There were no floats, no music, no boys in briefs. The cops turned their backs on us to convey their disdain, but the masses of people kept carrying signs and banners, chanting and waving to surprised onlookers.

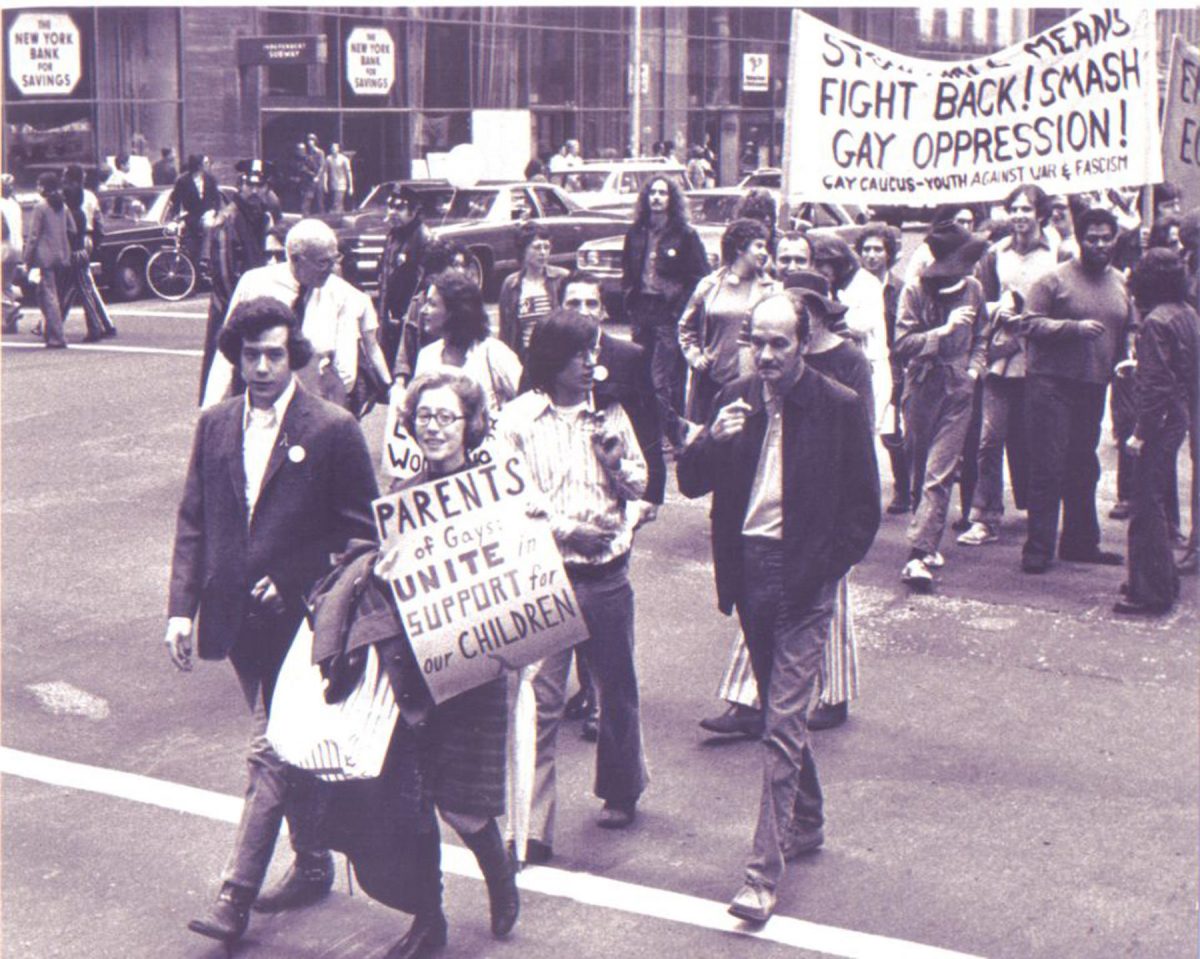

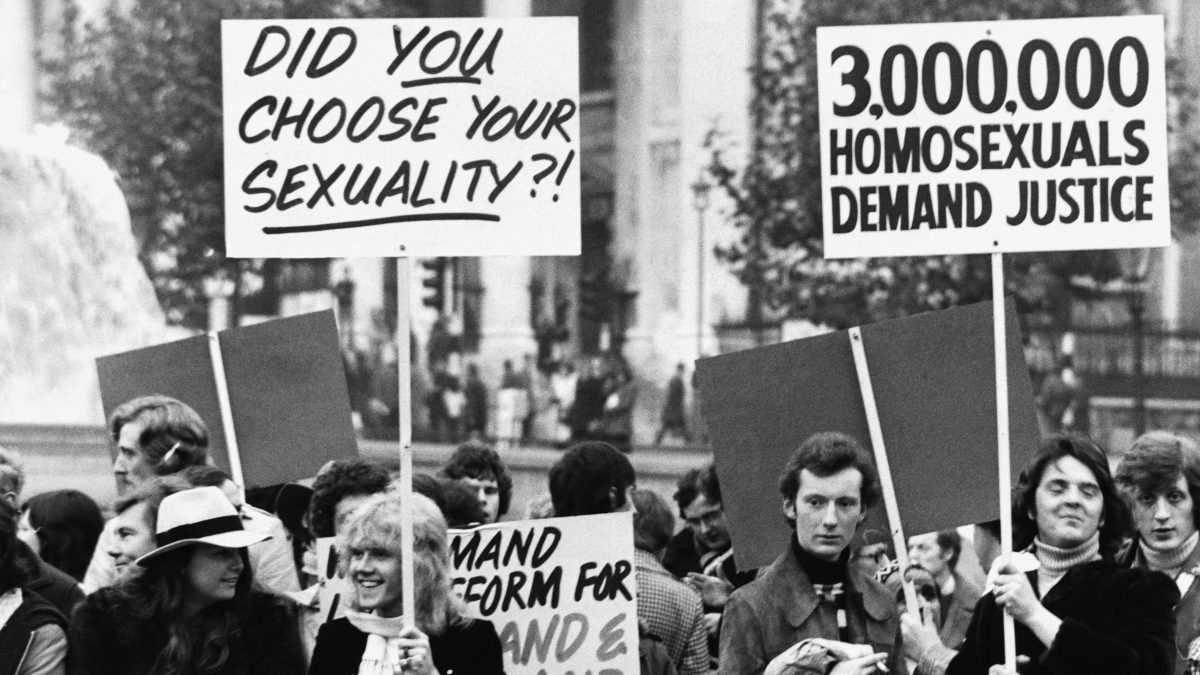

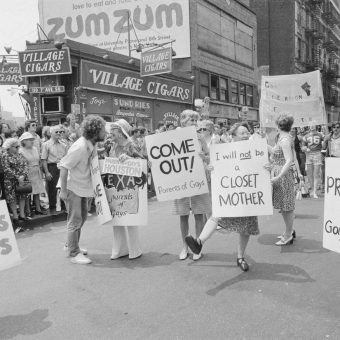

The heavily corporatized events we see now, with rainbow-colored police cars moving among the floats, were unthinkable when openly identifying as LGBTQ could cost a person their career. The GLF was right, the struggle would be long and hard, and it would hit a tragic roadblock in the following decades when the AIDS crisis and the woeful, malicious government response to the disease devastated the community that first rose up to forcefully challenge oppressive discrimination. But the work of these activists completely changed the approach to seeking justice by not only taking the fight to the streets in defiant acts of protest and celebration, but by making the support of parents, friends, and straight allies visible as well. This forced the press to pay attention and treat the movement with more than the usual scorn and contempt.

As Pride parades spread to other cities around the country in the early 70s, they were joined by an older generation of parents proudly holding up signs in support of their gay children. Jeanne Manford (above in 1972), whose son Morty had been arrested at Stonewall, formed PFLAG (Parents and Friends of Lesbians and Gays) after Morty was beaten at a protest rally by police. “It’s a little hard to imagine now what that period was like, how revolutionary it was for a parent to walk in the gay pride march in New York City,” says Eric Marcus, author of a history on the gay rights movement in the U.S.

The support of a wider community gave the movement more legitimacy than it had ever had before, but its radicalism went beyond mere acceptance. As activist and scholar Karla Jay recalls, “We had a much more radical hope. Our hope was that society would have changed in a dramatic way. I’m not talking about the legalization of marriage—I’m talking about a society in which sexual orientation wouldn’t matter, because people would view others as simple human beings.”

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.