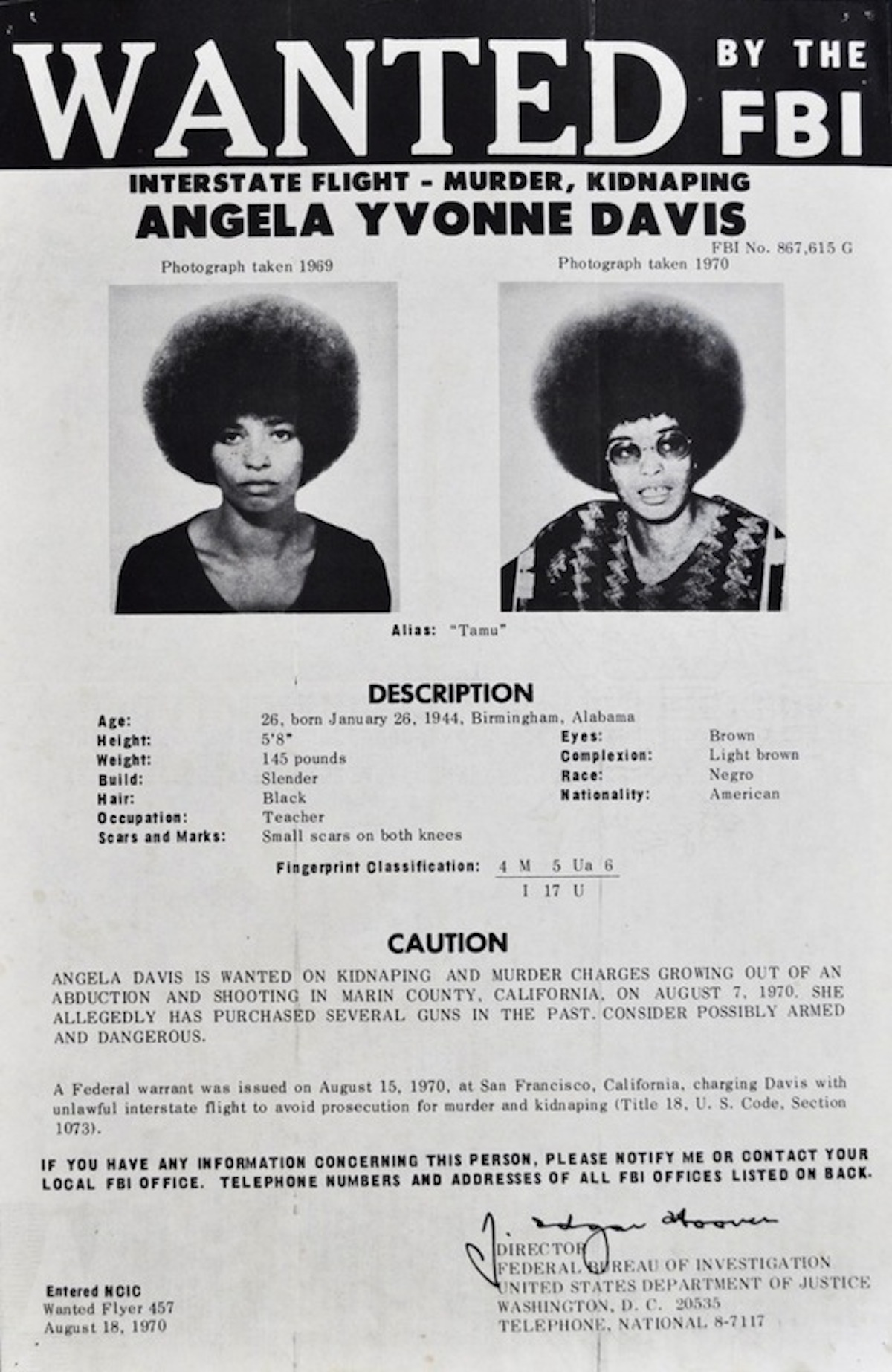

On August 18, 1970, Angela Yvonne Davis’s name was added to the FBI’s Ten Most Wanted List for kidnapping, murder, and interstate flight. Davis was already a darling of the left for her membership in the Communist Party and outspoken support for the Black Panthers, which caused then-California governor Ronald Reagan to personally orchestrate the 26-year-old’s dismissal from a teaching post at UCLA. Being hunted by J. Edgar Hoover for a crime she clearly did not commit took Davis’s celebrity to a whole new level, instantly making her as famous or infamous, depending on your point of view, as revolutionaries such as Che and Mao.

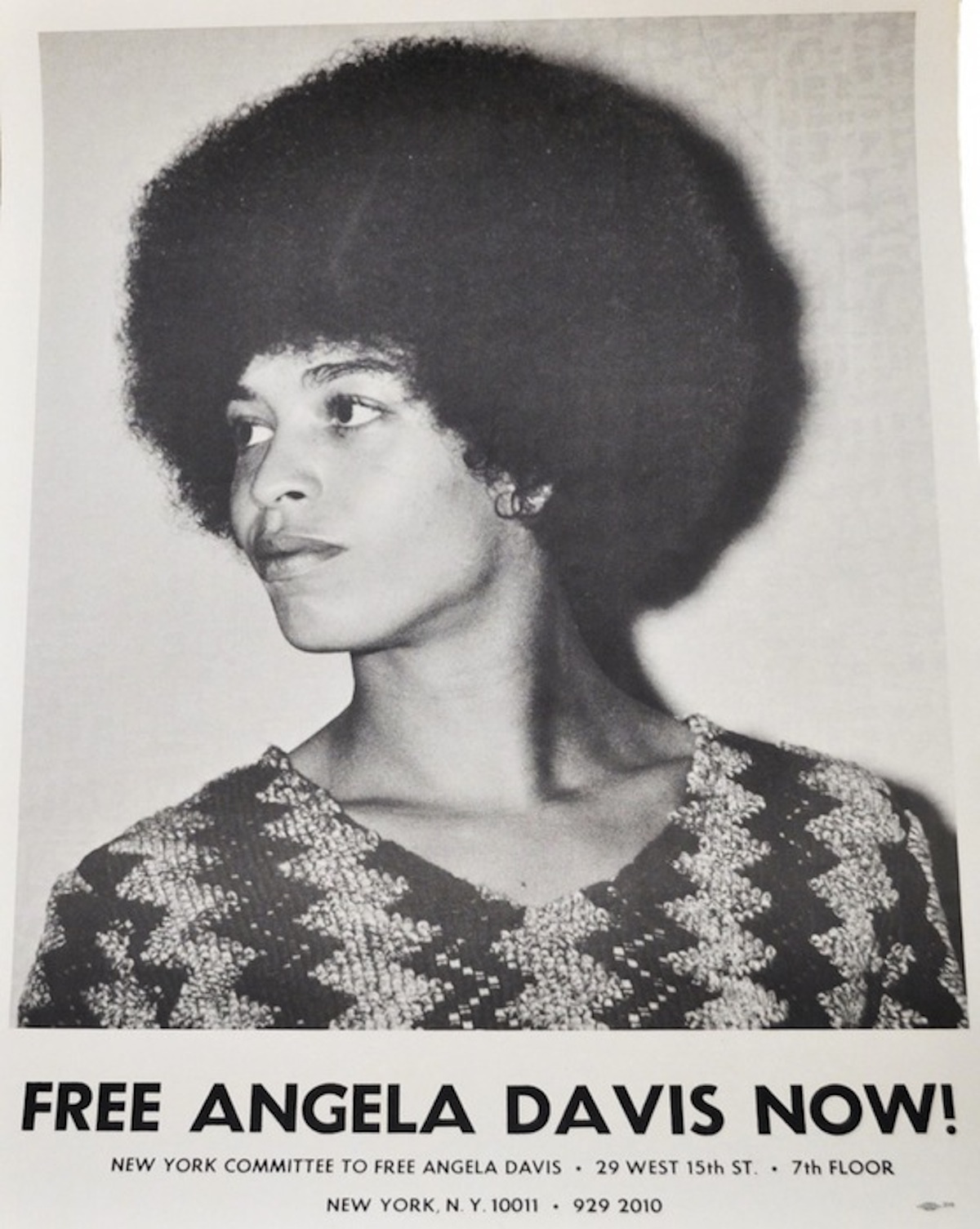

Almost from day one, posters were the way the world connected with Angela Davis. During the two months she was on the run, head shops did a brisk business selling reprints of the “Wanted” poster that graced the walls of post offices across the United States; by some accounts, Angela’s “Wanted” poster, with its appeal to call the FBI director personally at National 8-7117, was a better seller than hash pipes.

Angela Davis, first woman ever listed among the FBI’s Ten Most Wanted Fugitives, is escorted by two FBI agents after her arrest in New York on . She was being taken from FBI headquarters to the Women’s House of Detention. Wanted in connection with the August 7 California courtroom kidnapping, she was arrested in a midtown New York motel

13 Oct 1970

After she was apprehended on October 13, 1970, Davis’s release from prison became a cause célèbre—initially Aretha Franklin offered to post her bail, but in the end, after almost a year and a half in prison, it was a dairy farmer and a businessman who wrote the checks. During her incarceration, an international “Free Angela” movement sprang up. John Lennon and Yoko Ono recorded “Angela” for their album “Some Time in New York City.” Mick Jagger and Keith Richards wrote “Sweet Black Angel,” which was released on “Exile on Main Street.”

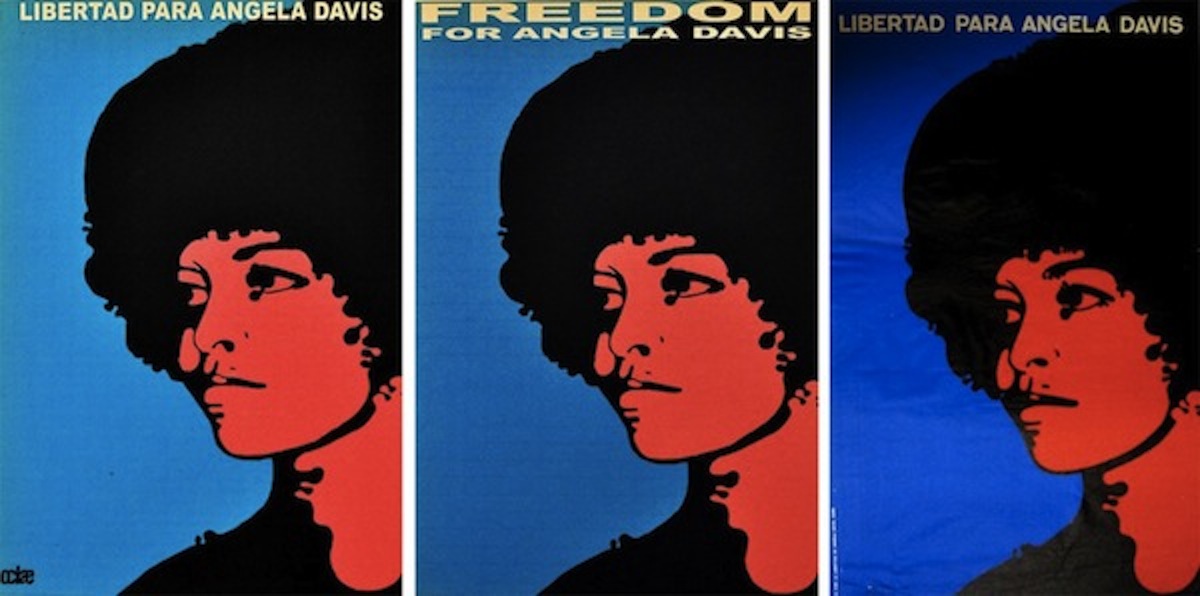

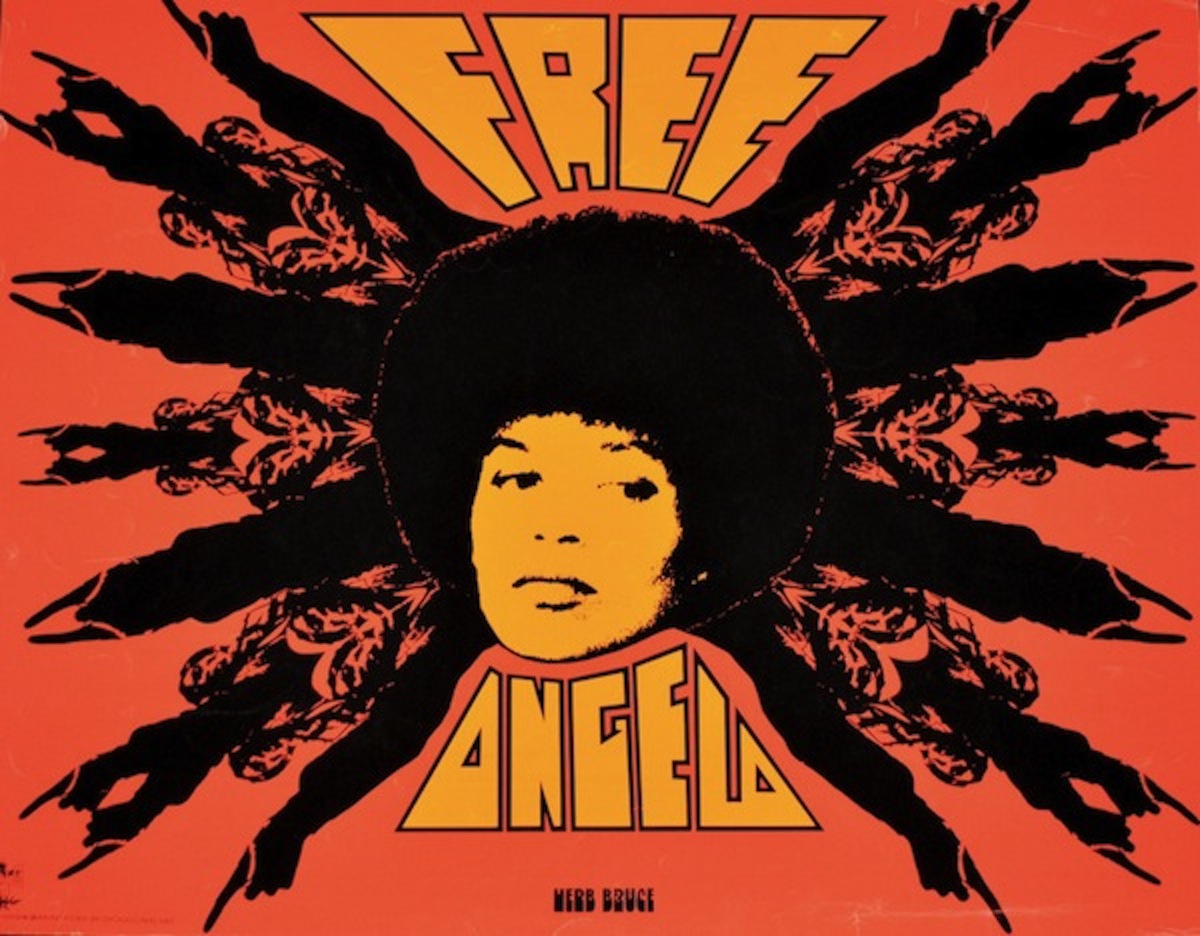

Above: Reprints of the FBI’s “Wanted” poster of Angela Davis graced the walls of many college dorm rooms in the fall of 1970 when Davis was on the run. Top: Three versions of Félix Beltrán’s most famous image of Angela Davis, first printed in Cuba in 1971.

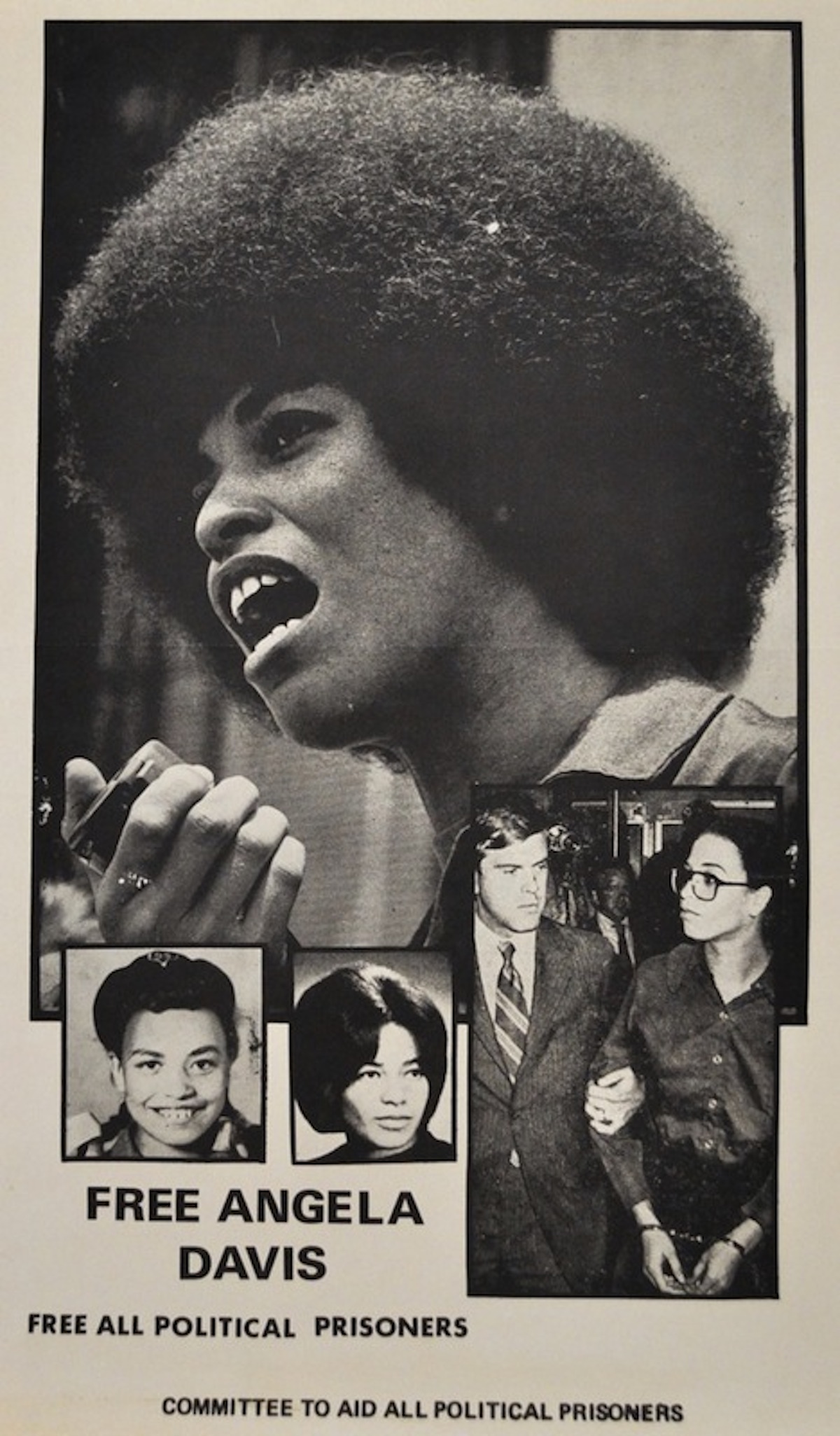

On the local level, hundreds of committees in the U.S. and abroad agitated for her freedom. Lacking the platform of a former Beatle or the Rolling Stones, these grassroots groups expressed their support via countless posters and flyers. Crowned by a halo of hair, Angela, as the world soon came to know her, was frequently depicted holding a microphone, her unflinching, clear-eyed features speaking truth to power.

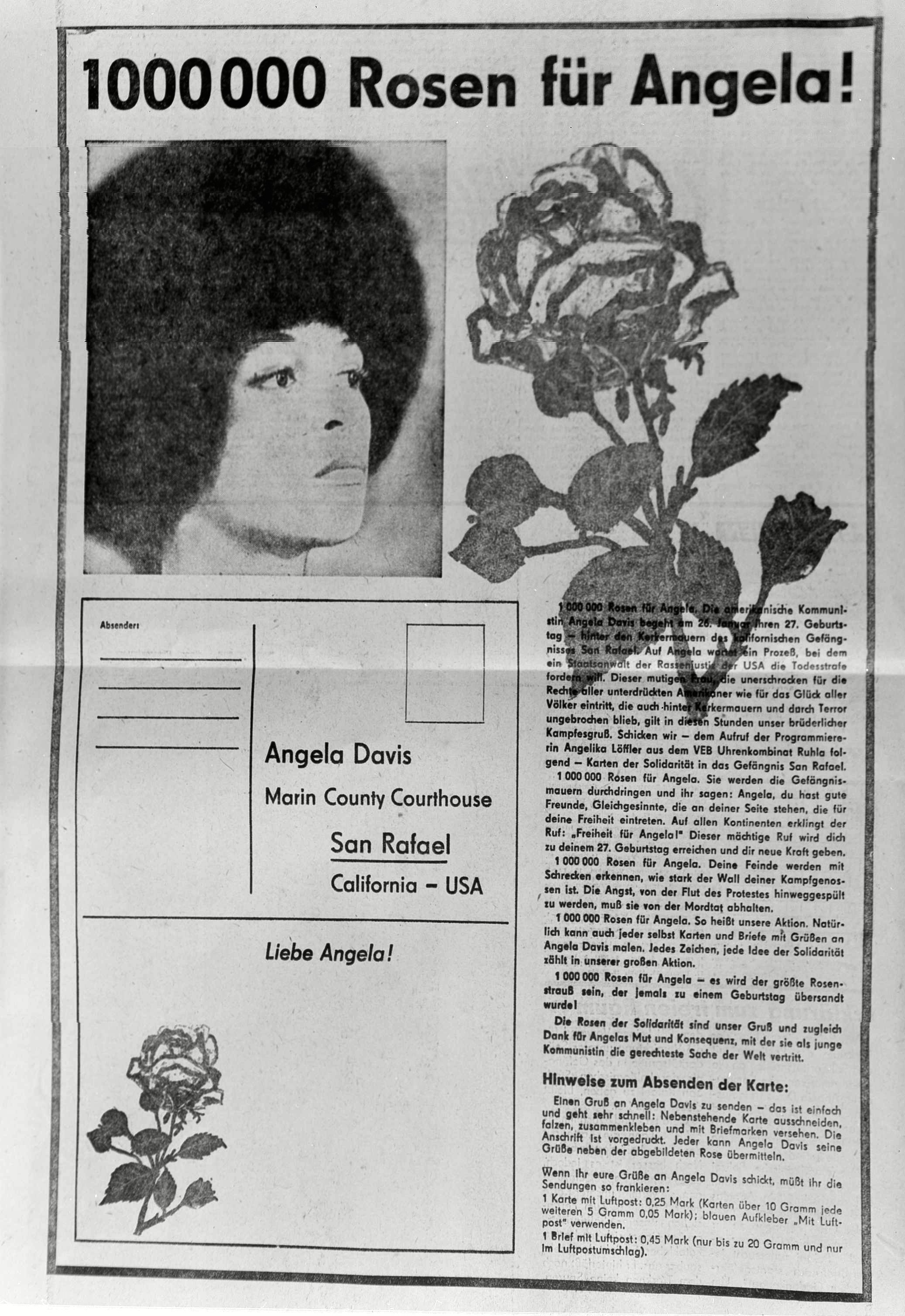

Angela Davis This is the layout of a page in the East German newspaper Wif, to send symbolic roses to Angela Davis, imprisoned American Black Power advocate

19 Jan 1971

Prior to her arrest, Davis had been an articulate advocate for what she called “the cause of freedom… the cause of my people,” and all those who were racially and economically oppressed. But it was Davis’s oppression (first she was fired from her position at UCLA for exercising her First Amendment rights, then she was denied bail for almost a year and a half when charged with a crime whose actual perpetrators were either in prison or dead) that made her a powerful voice of the protest movement, a symbol of social justice, and the face of political prisoners everywhere. To the chagrin, no doubt, of her detractors, her imprisonment only served to spread her message more quickly and widely.

Posters of Davis were the key way supporters spread her message in that pre-Internet era. “Because of her giant ’Fro and her role in the Communist and Black Panther parties, Angela Davis was a role model for a lot of different people, so it wasn’t a total surprise that her imagery became pretty dominant,” says author and archivist Lincoln Cushing, who has curated several exhibitions about political art, including “All of Us or None” at the Oakland Museum of California in 2012. “I grew up with a lot of the New Left, Black Panther Party, and United Farm Workers messaging as a teenager,” he says. “Images of heroic revolutionaries and martyrs were pretty popular.”

The most reproduced photograph of Angela was the one of her holding a microphone at a rally in the spring on 1970. It was reproduced on page 24 of a “Life” magazine cover-story article, published on September 11, 1970, and titled “The Making of a Fugitive.” The photographer is unknown.

The most reproduced photograph of Angela was the one of her holding a microphone at a rally in the spring on 1970. It was reproduced on page 24 of a “Life” magazine cover-story article, published on September 11, 1970, and titled “The Making of a Fugitive.” The photographer is unknown.

The circumstances that led to Angela’s flight, capture, and imprisonment were hard to follow then, and are probably unfamiliar to most people today. The event itself unfolded on August 7, 1970, when a 17-year-old named Jonathan Jackson walked into the San Rafael, California, courtroom of Superior Court Judge Harold Haley, carrying a bowling bag and wearing a raincoat, despite the heat of the day. Nodding casually to the bailiff, the young man took a seat in the gallery to observe the trial of a San Quentin State Prison inmate named James McClain.

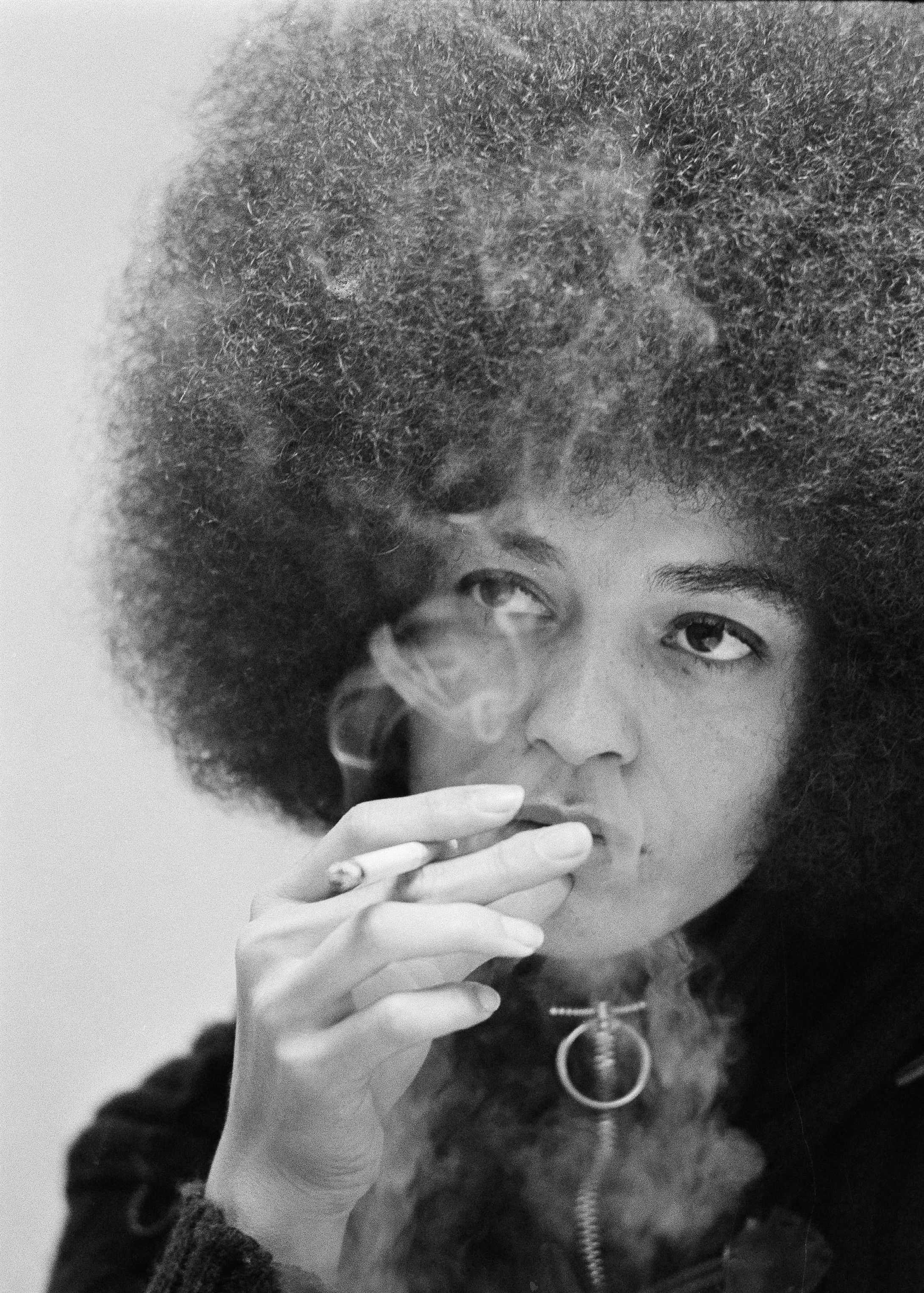

Angela Davis Angela Davis, black Communist jailed for more than a year on murder-conspiracy charges resulting from San Rafael courthouse slaying of a judge and three others, has a cigarette as she talks during an exclusive interview with Associated Press reporters Edith Lederer and Jeannine Yoemans in tiny green interview room at Santa Clara County jail at Palo Alto – 27 Dec 1971

Like Jackson’s older brother George, who was behind bars at Soledad State Prison, McClain was accused of murdering a prison guard. On the stand that day was Ruchell Magee, one of several San Quentin inmates who’d been brought to the new Frank Lloyd Wright-designed Hall of Justice building to testify at McClain’s trial.

Within minutes of sitting down, Jackson abruptly stood back up, pulled a gun from under his coat, and ordered everyone to “freeze.” After the weapons in his bag were distributed to McClain, Magee, and a third San Quentin inmate named William Christmas, Jackson and his accomplices took five hostages—Assistant District Attorney Gary Thomas, Judge Haley, and three jurors—all of whom they intended to trade for the release of George Jackson and his alleged accomplices, known as the Soledad Brothers.

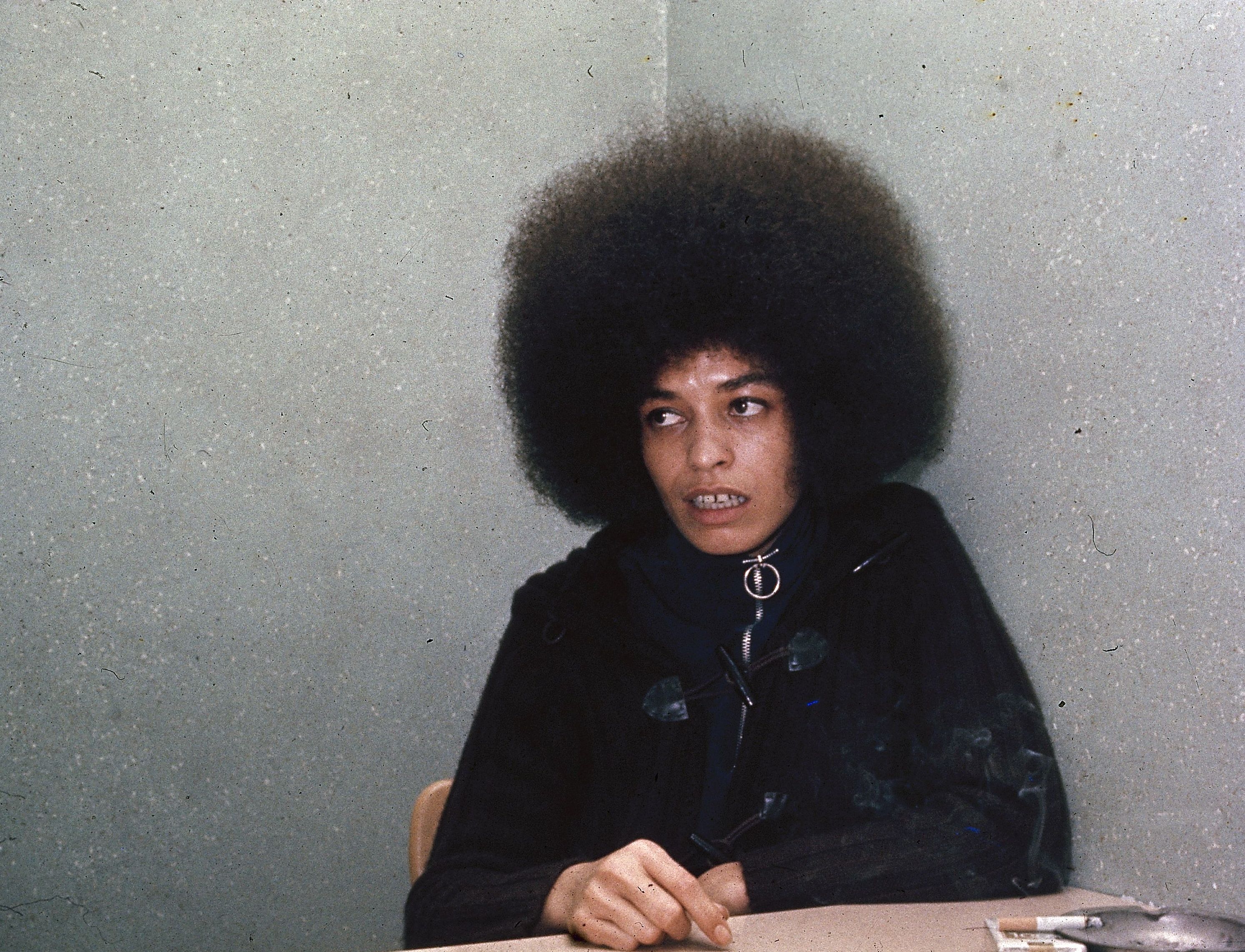

F. Joseph Crawford’s photograph of Angela in 1969 was the source for Félix Beltrán’s 1971 poster.

Taping the barrel of a sawed-off shotgun to Haley’s neck, the nine made it out of the courtroom and as far as Jackson’s parked Hertz van. They were starting to pull away when a San Quentin guard, armed with a 30-30 rifle, shot the driver.

Then all hell broke loose. As soon as the driver was incapacitated, District Attorney Thomas grabbed the man’s gun and shot the other three kidnapers inside the van, but not before someone pulled the trigger on the shotgun, blowing off, as one newspaper account put it, half of Judge Haley’s head. Meanwhile, sharpshooters peppered the vehicle with bullets (the judge was also shot in the chest, probably by a bullet that originated outside the van). In the end, Jackson, McClain, Christmas, and Judge Haley were dead, while the D.A., Magee, and one of the jurors were wounded. Miraculously, two hostages went unharmed.

Three of the guns Jackson brought into Haley’s courtroom that day, including the shotgun, were registered to Angela Davis, who purchased the shotgun at a San Francisco pawn shop on August 5, just two days before the judge’s murder. Sometime between the 5th and the 7th, the shotgun was sawed off and added to Jackson’s arsenal.

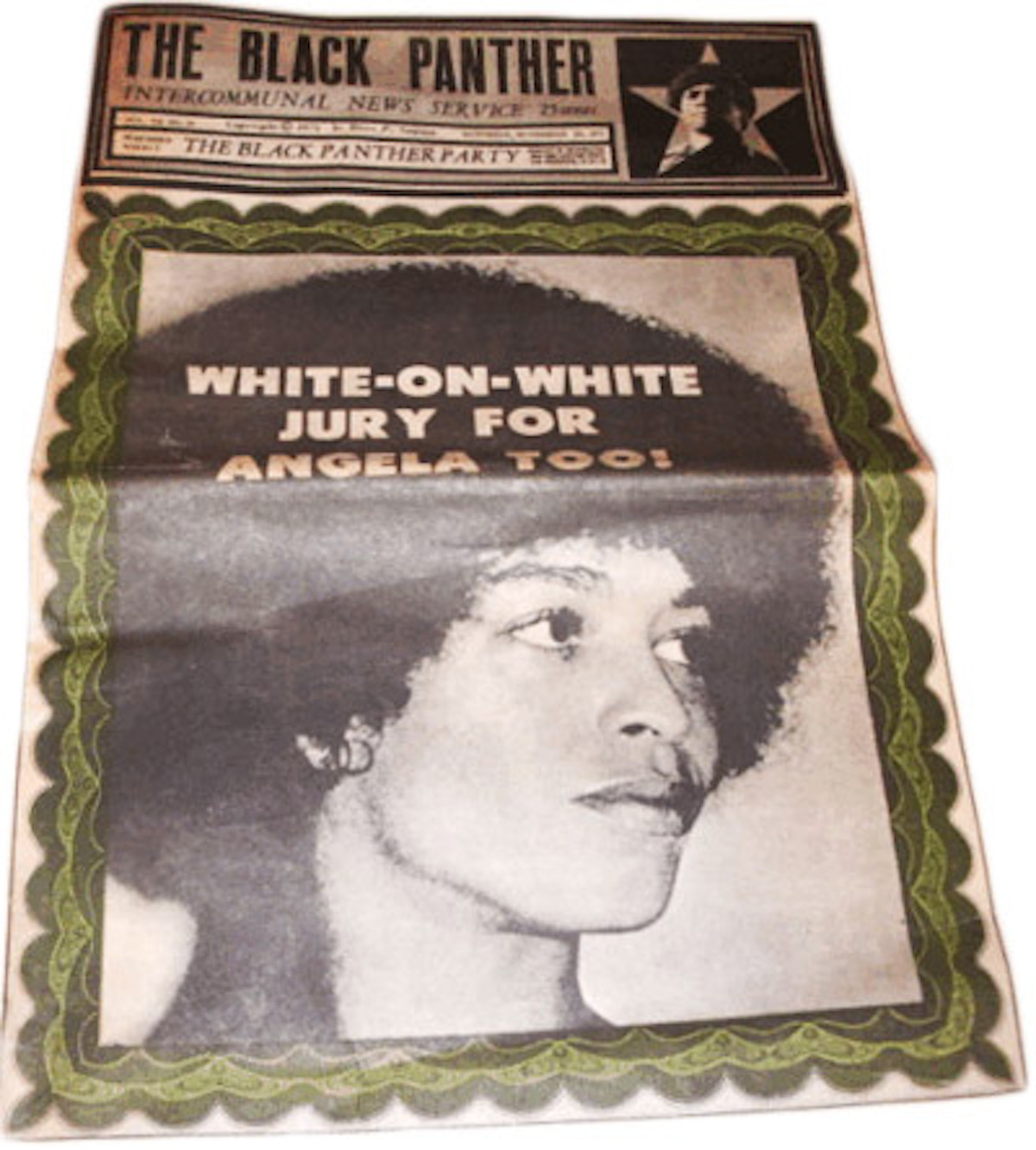

When “The Black Panther” put Crawford’s photo on its cover, they flopped the image.

Almost two years later, on June 4, 1972, after a 13-week trial, Davis was acquitted on all three of the counts against her. Though letters between Davis and George Jackson were introduced as evidence of a motive on Davis’s part to have supplied weapons to Jackson’s younger brother, the jury believed the testimony of witnesses who stated that the guns had been purchased, as permitted under the Second Amendment, for security purposes at the headquarters of the Soledad Brothers defense committee. After the verdicts were read, Davis, as well as some of the jurors, cried tears of relief and joy.

Many people, even those from subsequent generations, empathized with that human side of Angela Davis, but for some, the meaning of Angela could be even more personal. “I never saw Angela as an icon,” says poster collector and fellow archivist Lisbet Tellefsen, who has known Davis socially since about 1980 and who, according to Cushing, may have the largest collection of Angela imagery in the United States. “I saw her as a righteous woman, a sister, an elder who didn’t crack. A lot of the older folks I grew up around were disillusioned and broken. But Angela just stayed true to her beliefs, lived her beliefs. It was really powerful to have a model like that.”

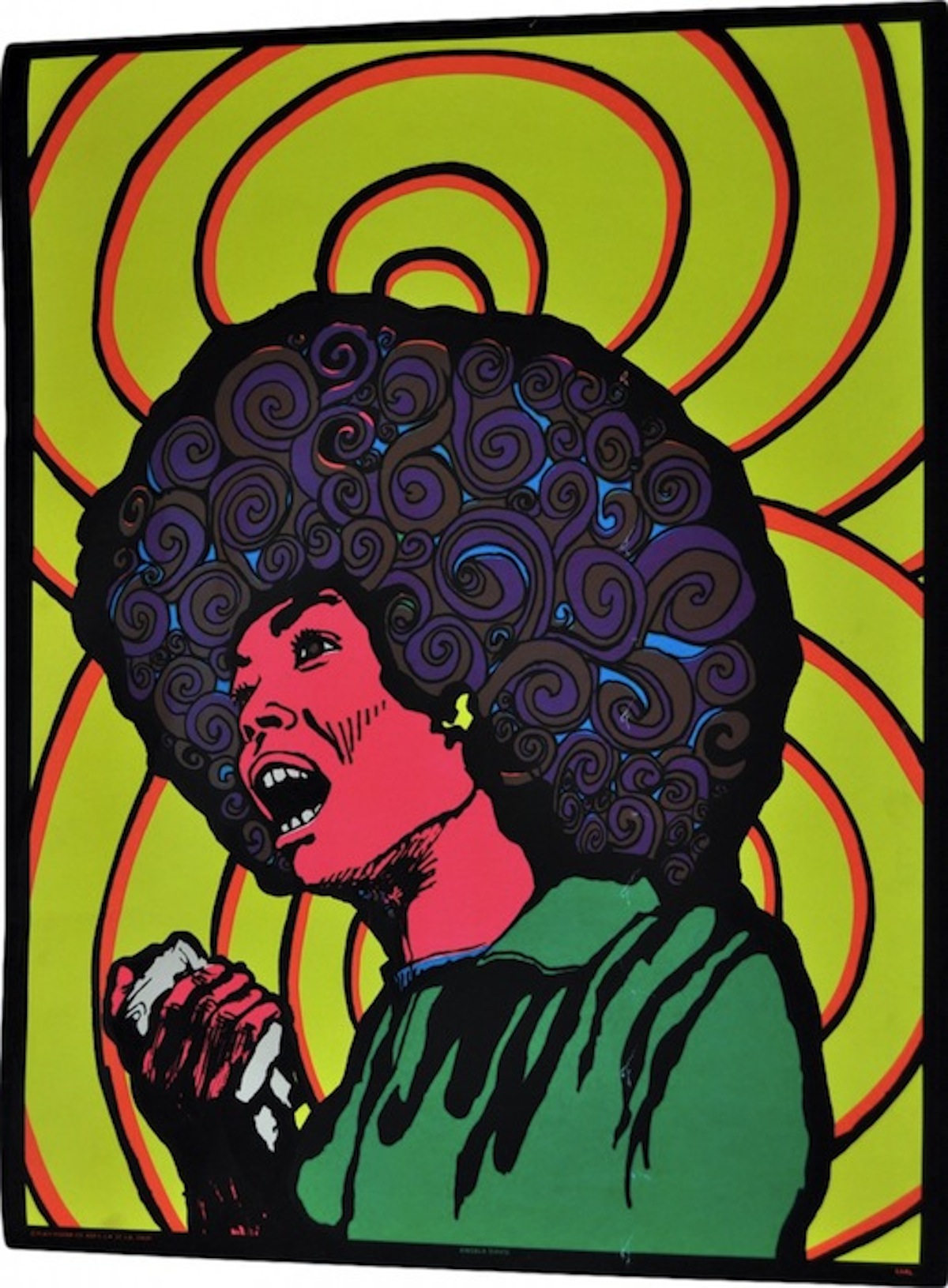

Tellefsen’s light-filled studio fairly brims with images of Angela, which stare back at you on everything from protest art to newspaper clippings, all of which are obsessively organized. Tellefsen has so many posters of Angela Davis, she gives them their own informal classifications. For example, there are examples in which Angela appears almost angelic, what Tellefsen calls the “black is beautiful” posters. “They were produced by the black community, for the black community,” she says. “It was really about the promotion of her image as a strong black sister.” Examples include posters by illustrator David Mosley.

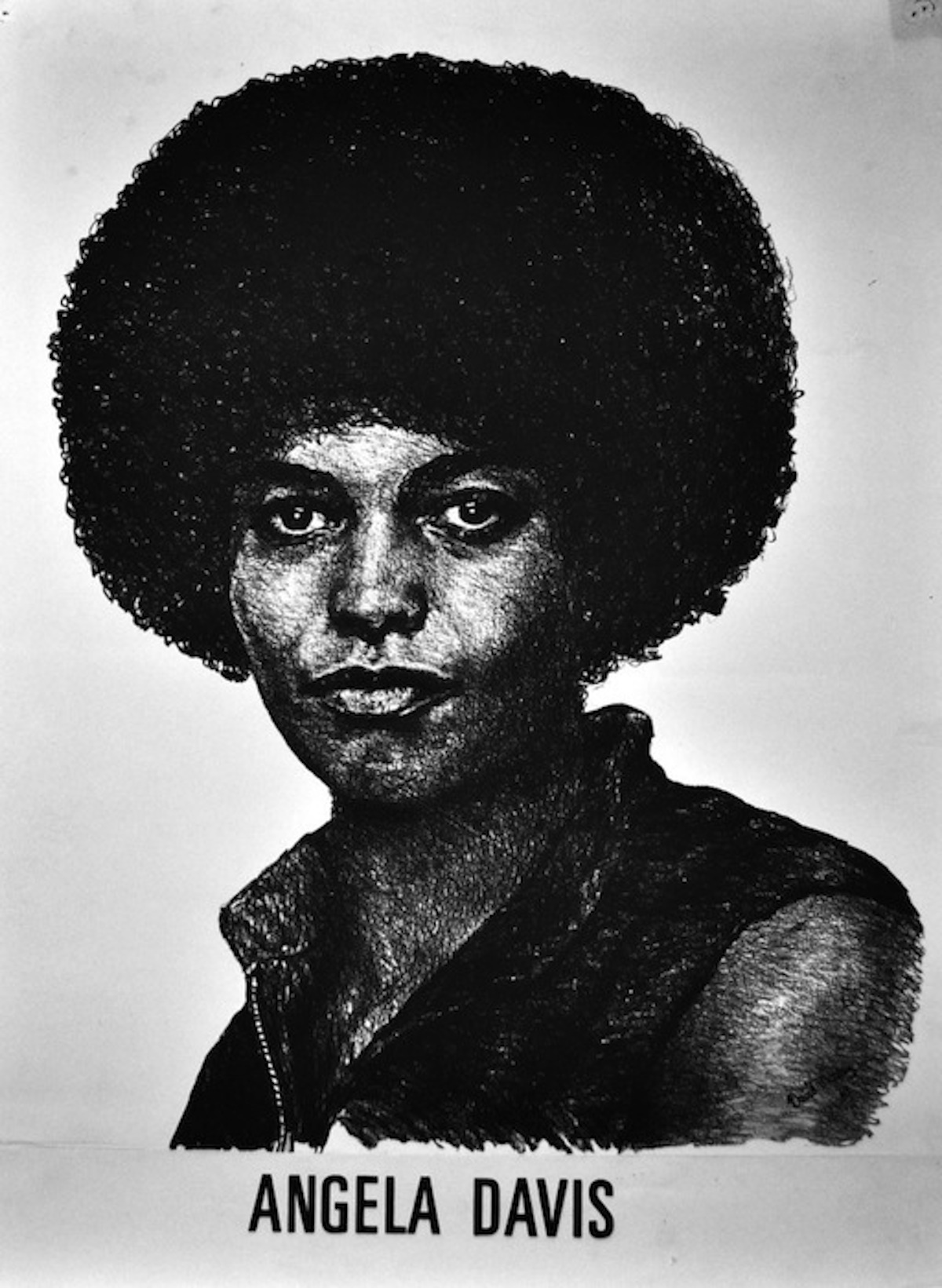

Images of Angela created for the black community by artists such David Mosley portrayed Davis as a “strong black sister.”

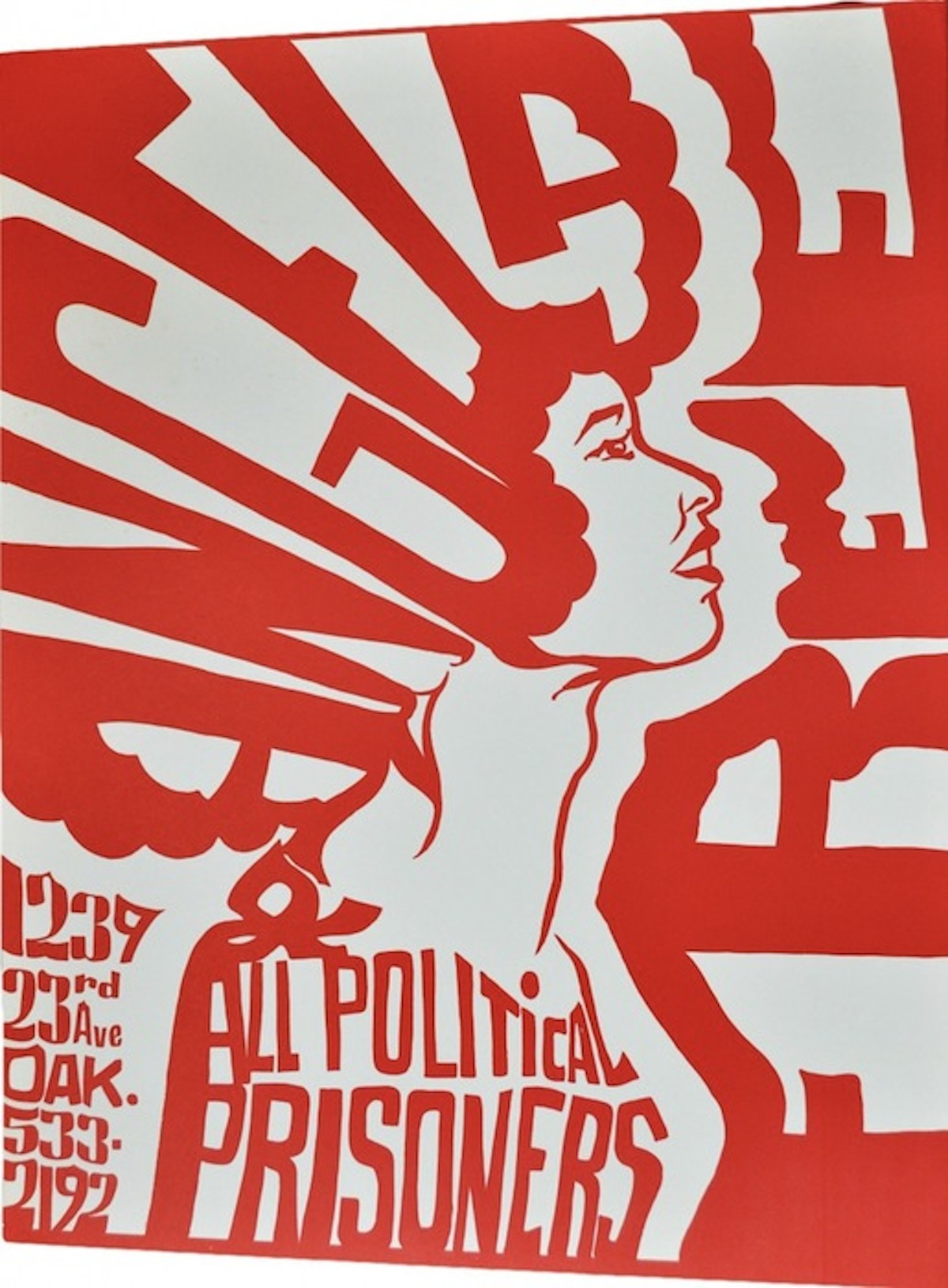

Then there are the campaign and fundraising posters, which are all business and often poorly designed from an artistic standpoint. “These were purely functional,” Tellefsen agrees. “They were the ones promoting her defense fund, designed just to get the information out.”

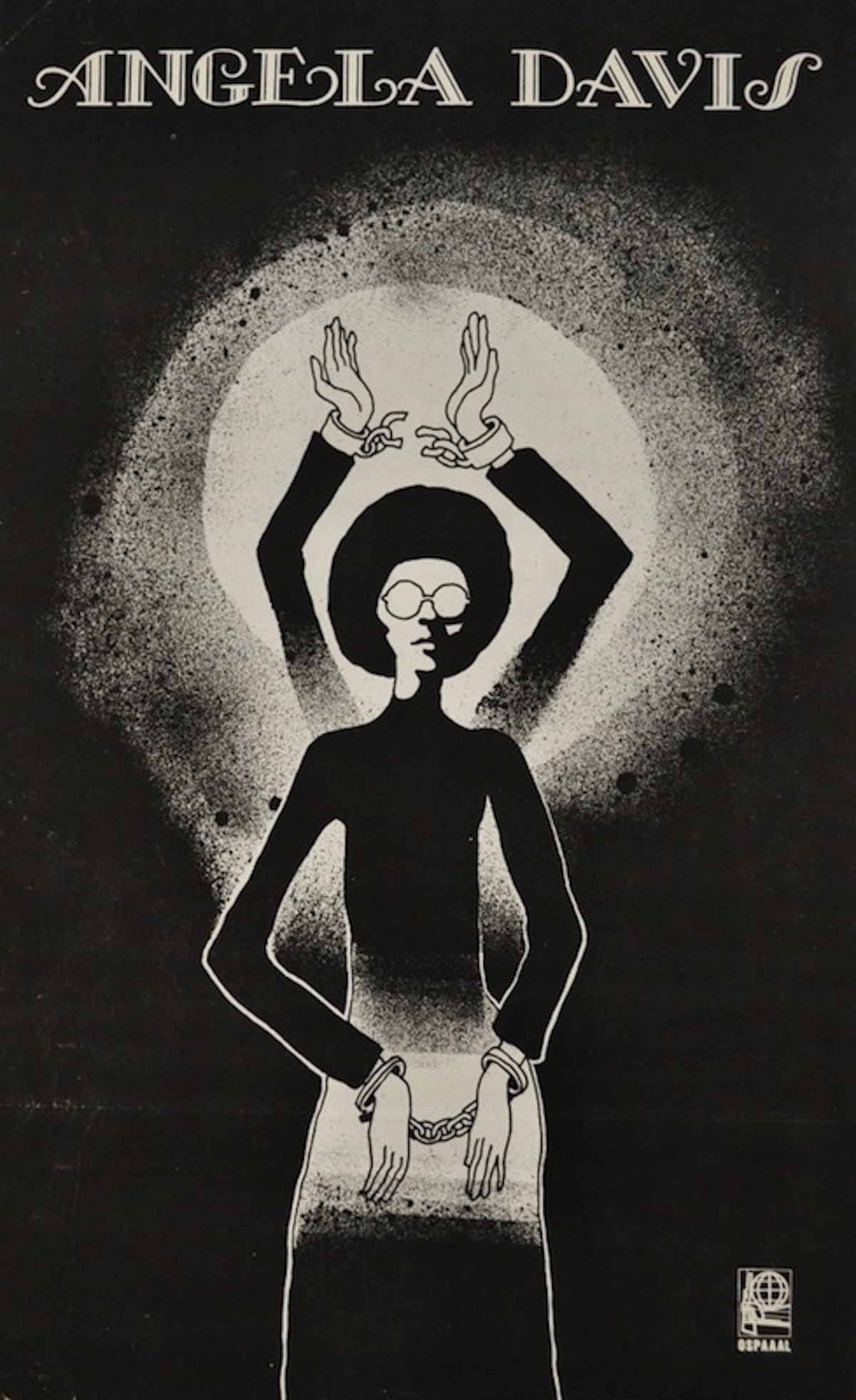

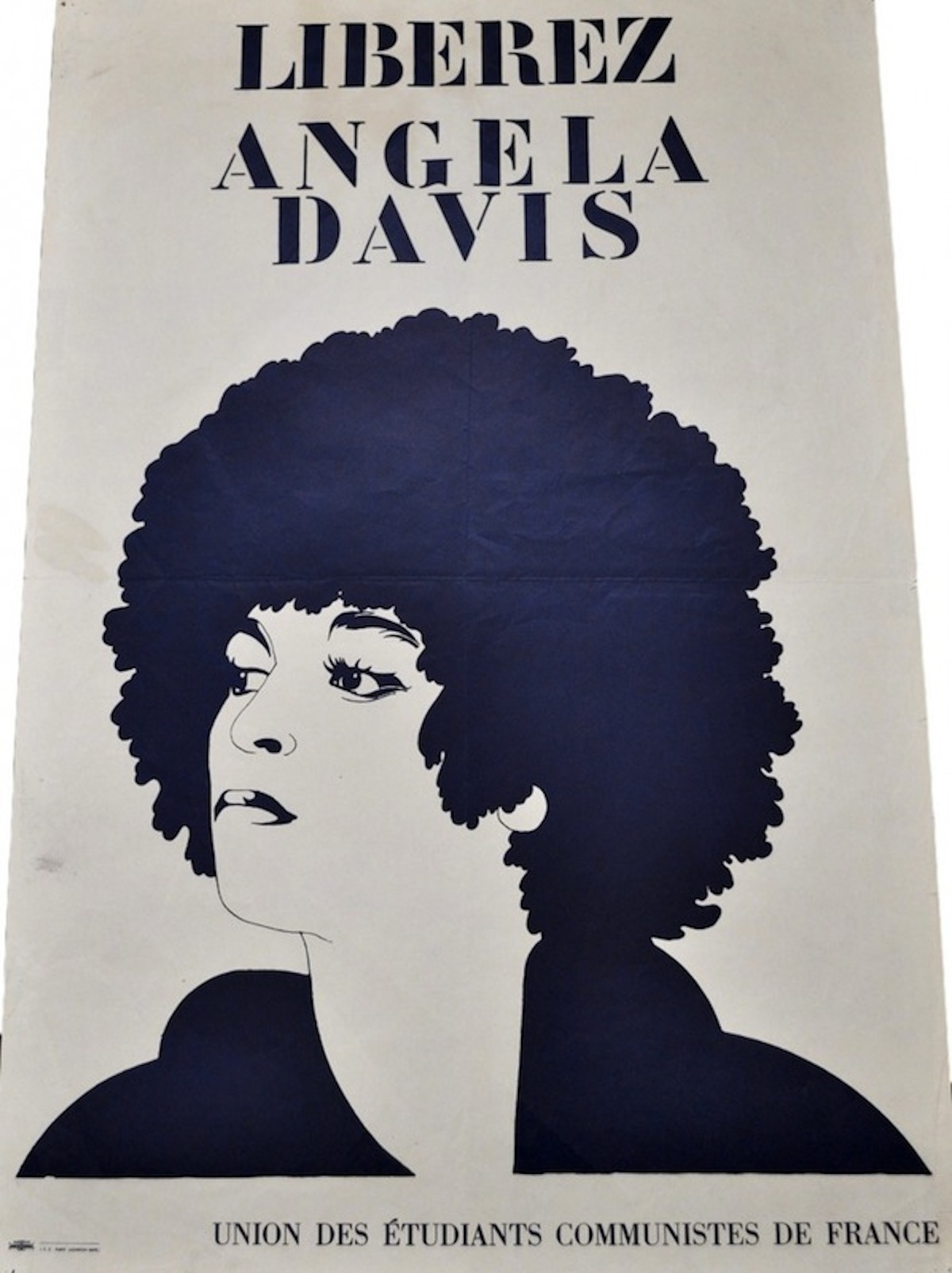

The international Angelas are some of Tellefsens favorites. “Look at these two,” she says excitedly, pulling out a black-and-white poster printed by the Havana-based Organization in Solidarity with the People of Africa, Asia, and Latin America (OSPAAAL), followed by a blue-on-white drawing from a Paris group called the Union des Étudiants Communistes de France. “The Cubans focus on her strength. She’s in chains, but she’s not broken. Here,” she says, pointing to the French, almost Lena Horne-like portrait of Angela, “she’s soft and beautiful.”

Like most collections, Tellefsen’s Angelas evolved from childhood experiences. “I was raised in paper,” she says, “collecting is in my DNA. My mother was a Norwegian citizen and my father figure was a very active, black communist. He was always the one who was the secretary, who did the bookkeeping and basically kept all the paper. As a kid, I traveled a lot, and my constant companion was this little suitcase where I would obsessively gather the programs and tickets we collected going from place to place. I guess I felt like someday I might need to remember. It was almost like treating my life like a jigsaw puzzle.”

The message on “Free Angela” posters quickly evolved to add “& All Political Prisoners.”

Posters soon caught her eye. “Posters are really suited to me,” she says. “I love design, I love graphics. Just as important is the act of building a collection, to assemble things that have never been assembled before.”

That certainly describes Tellefsen’s Angela posters. Most them were acquired in the usual ways (eBay, etc.), but some of her Angelas came from the source herself. “We went to her storage unit,” says Tellefsen, recalling one particularly memorable visit with Angela Davis, “and she gave me all her extra posters. She had a ton of the fundraising ones,” Tellefsen adds.

Another break came when she met Lincoln Cushing. “I had always been attracted to different graphic styles,” she says, “and one day I heard that Lincoln had written a book on Cuban posters and was giving a talk. So I went, and at the end of his presentation, he pointed to this guy in the audience, saying something like, ‘I’d like to thank Michael Rossman, whose 25,000-poster collection was the basis for a lot of my book.’ And I’m looking at this old hippie, and I’m like, ‘Oh my God, 25,000 posters!’

A poster printed in Cuba shows Angela breaking her chains.

“At the end of the talk, I introduced myself to Michael,” Tellefsen continues, “and he was really friendly and invited me over. I guess to make it sexy for me he pulled out the Angela/Panther stuff. And I said, ‘Have you ever thought about digitizing this?’ And he said, ‘Lincoln and I have been working on it, on and off, but we’d love some help.’ So the three of us formed this little group to digitize his collection. They had already built a system, which was like a vacuum box on the wall, solving the problems of lighting and skew. At that point, we were shooting archival slides. My job was to get the slides produced and digitized. Lincoln was the cool scholar-dude-author. Michael was the visionary, mad collector.”

Add “generous” to that list. Before he passed away in 2008, Rossman helped Tellefsen build her Angela Davis collection. “I was really lucky to be able to trade with Michael,” she says. “With Angela Davis, it’s usually one-offs, people that have a poster that hung on their wall back in the day. Michael had a lot of duplicates. That was huge. This kind of collection is not something you can easily build.”

A French “Free Angela” poster highlights Davis’s beauty.

Recently, I joined the one-off club when I acquired my first Angela Davis poster, a three-color, 13 1/2 by 21 1/2 inch offset (or so I think) printed on very thin paper. While the actual date of its printing is probably impossible to pin down today, the person I acquired it from had had it since the 1970s, so it’s at least that old.

Tellefsen may have one of the largest collections of Angela posters, but she doesn’t have one exactly like my fragile red, black, and blue sheet of paper featuring Angela’s stylized profile below the words “Libertad Para Angela Davis.” Her versions are all much smaller and have different credits on them, although they share the same designer, an artist named Félix Beltrán, who was living in Cuba in 1971 when orders came down from the Revolutionary Orientation Department of the Central Committee of the Communist Party, for whom he worked, to create a poster advocating for the release of a fellow Communist and revolutionary in the United States named Angela Davis.

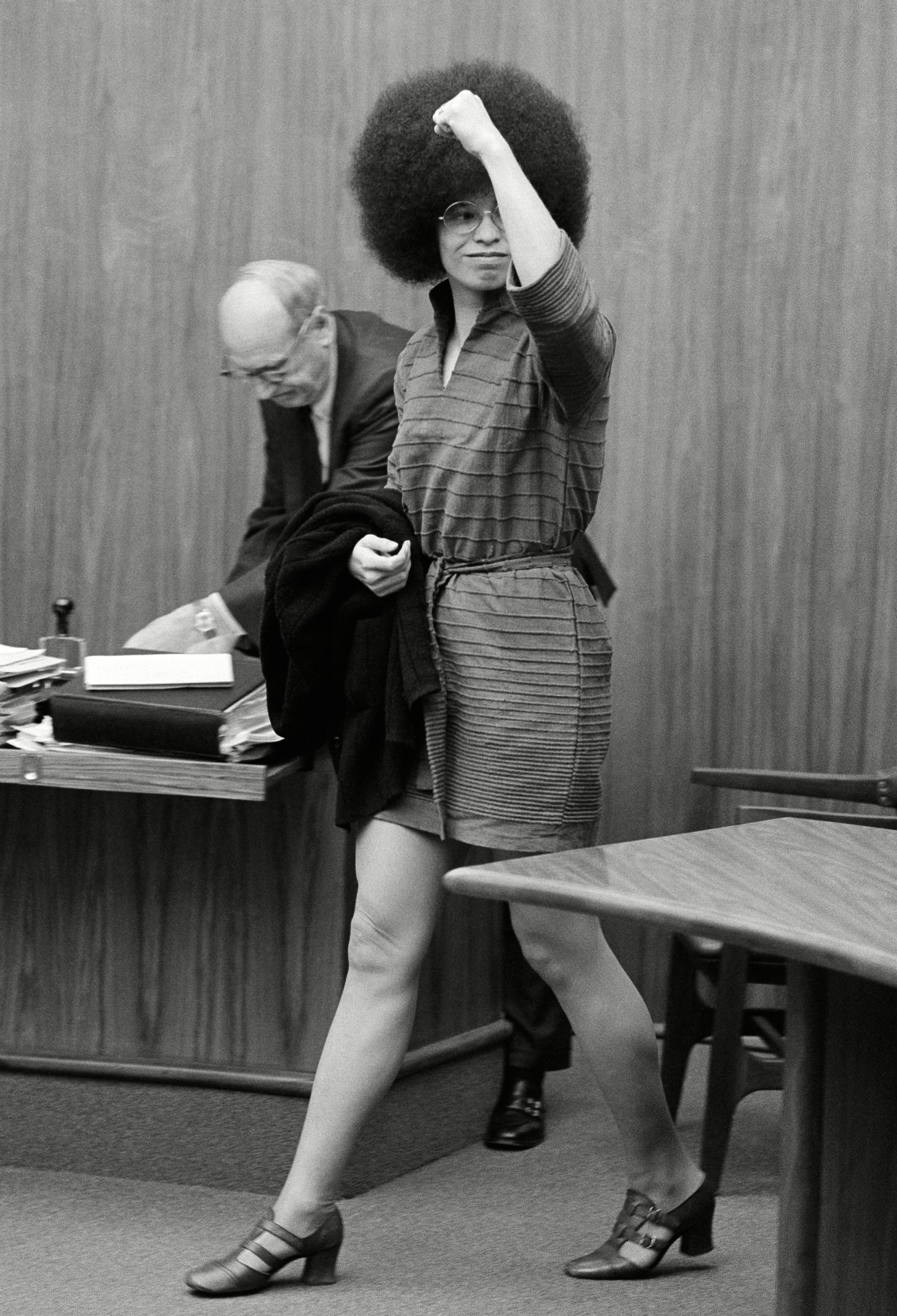

Radical spokeswoman Angela Davis is shown in 1971

Angela Davis, USA

Back in 1971, Beltrán was one of Cuba’s leading graphic artists and designers (in the mid-1980s, he moved to Mexico, where he still lives). Along with René Mederos and Alfredo Rostgaard, Beltrán gave the graphic exports of Cuba their Pop Art, at times almost psychedelic, look. In stature, Beltrán was his nation’s Milton Glaser, directing the “identity design,” as he calls it today (via email and a translator) of the Cuban Pavilions at Expo 67 in Montreal and Expo 70 in Osaka.

Two images of Angela that Félix Beltrán worked on in 1971 but never developed into posters (at left and right), plus a lesser-known poster (center) he created featuring an image of Angela as a teenager.

Two images of Angela that Félix Beltrán worked on in 1971 but never developed into posters (at left and right), plus a lesser-known poster (center) he created featuring an image of Angela as a teenager.

According to Beltrán, who says he has never spoken to Angela Davis, the Revolutionary Orientation Department supplied him with several photographs to use as sources for his poster. He tried a number of them, and several were printed, but the most famous one appears to have been taken from a photo that Tellefsen has identified as the work of F. Joseph Crawford, who snapped an image of Angela at a press conference in New York City on September 9, 1969. “That photo was used in several early posters produced by the N.Y. Committee to Free Angela Davis,” says Tellefsen. To my eye, it also looks like the source of Beltrán’s “Libertad Para Angela Davis” poster.

Beltrán gave Crawford’s photograph a stylized look that abstracted the curls in Davis’s hair and some of the shadows on her face and neck. It was a style, Beltrán says, he had used in murals created for the Cuban Pavilion in Osaka, and it lent itself to screen printing, essentially replacing the tiny, halftone printing dots in his source image with expanded, ornamental drips and blobs that bled into fields of pure color.

Those colors were deliberate, too. “The red color combined with blue,” Beltrán says, was supposed to evoke “the U.S. flag.” Except, fittingly, Beltrán’s Angela flag, as it were, was dominated by black rather than white.

Angela with the microphone, psychedelic-style.

The original “Libertad Para Angela Davis” poster, Beltrán says, “was a screen-printed poster, on cardboard, not paper, and it was printed in several thousands.” Some of these originals were sent to other countries for duplication. “It is possible that the poster entered the U.S. through the Representation of Cuba at the United Nations, which had diplomatic immunity,” he says.

Credits on Beltrán’s poster generally run up the lower-left side or at the bottom. Mine reads “Comte Por La Libertad De Angela Davis, Cuba.” “The original credit of the poster was for the ‘Revolutionary Orientation Department’; I think it was just like that,” Beltrán says, although he is not 100 percent certain. “I don’t have any of the first copies,” he says, “because all of my belongings were confiscated when I decided to live in Mexico.” But Beltrán does remember one detail about his original versus the subsequent reprints: Angela Davis’s “hairdo,” as he calls her Afro, occupied more space in his first printing. For what it’s worth, my Angela poster has more hair in the top-right corner than Tellefsen’s, but I will probably never know if that detail means anything.

This head-shop-style Angela poster is similar to the one above it, but the message is unambiguous.

Which is probably just as well, because while fixating on dimensions and credits is something poster geeks enjoy, it’s the message of Angela Davis posters that’s ultimately most important. In fact, sometimes the personality cult that grew up around Angela got in the way of what her supporters were trying to say. “The poster was created by me in the beginning of 1971,” says Beltrán, “and is one of the most reinterpreted posters of the end of the 20th century. For me, it is an honor to see it framed in homes as if it was a painting. But I am concerned that this has happened due to the attractiveness of the poster, not its content, which for me is most important.”

“Once you start putting faces to movements,” says Cushing, “they tend to take on a life of their own. The most obvious example is Che Guevara. There are people who wear a Che Guevara t-shirt but have no idea who the hell this guy was. Certain images become iconic on their own and start to lose their historical roots. Angela’s image is a notch or two below that of Che’s, but it’s the same effect.”

Today, Che t-shirts are viewed as just another example of shrewd marketing, but back in the day, the tendency of people to support causes based on the attractiveness and perceived coolness of their leaders was known derisively as “radical chic.” As the Minster of Culture for the Black Panther Party from 1967 to 1980, artist Emory Douglas was one of those radicals it was chic to support. “Of course,” he says today, “that was present throughout the whole movement. But that’s a level of consciousness that can be raised to another level of consciousness.”

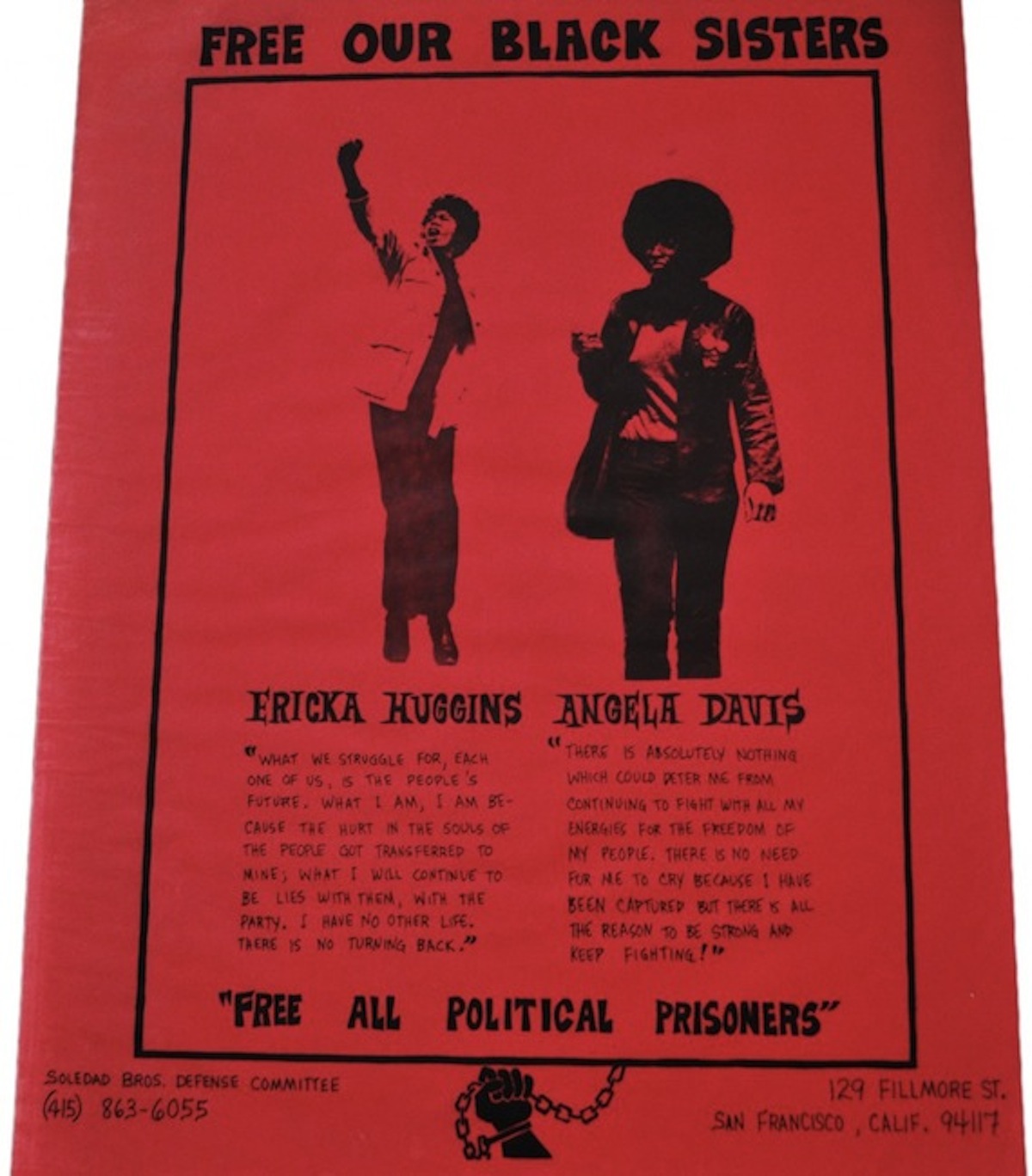

Angela was often paired on posters with Ericka Huggins, who was the leader of the Black Panther Party in Los Angeles in 1969, when she was arrested with party co-founder Bobby Seale.

Angela was often paired on posters with Ericka Huggins, who was the leader of the Black Panther Party in Los Angeles in 1969, when she was arrested with party co-founder Bobby Seale.

For Douglas, even superficial support represented an opportunity to educate. The role of political art, he says, is “always to inform, enlighten, and perhaps inspire, to get the message across in a way that when people look at it, so that even a child can get something out of it.”

In the case of the Panthers, the messages promoted in The Black Panther newspaper included calls to boycott lettuce in support of the United Farm Workers, to vote for Black Panther Party co-founder Bobby Seale when he was running for mayor of Oakland, and to help the elderly through a program called Seniors Against a Fearful Environment. There were also lots of images that look straight out of the Occupy movement of 2011, such as Douglas’s 1974 collage of a corporate-logo’ed hand manipulating the strings of a puppetized caricature of President Gerald Ford, all against a background of the New York Stock Exchange transactions page from the New York Times.

And, of course, there was Angela. “We designed covers around her case, where her picture was used with ‘Free Angela’ and talking about the white-on-white jury with no people of her peers, those kinds of things.” In fact, the same source photo that Beltrán used on his poster ran on the cover of The Black Panther, only it was flopped.

Artist Shepard Fairey has created numerous posters of Angela Davis. The one on the left, “Rough Angela,” 2003, was taken from Félix Beltrán’s famous 1971 poster. The one on the right, “Peace Angela,” 2005, is based on a Stephen Shames photo from 1972.

Artist Shepard Fairey has created numerous posters of Angela Davis. The one on the left, “Rough Angela,” 2003, was taken from Félix Beltrán’s famous 1971 poster. The one on the right, “Peace Angela,” 2005, is based on a Stephen Shames photo from 1972.

More recently, in 2003, Shepard Fairey appropriated F. Joseph Crawford’s photograph, as re-imagined by Félix Beltrán, for a poster called “Angela Rough.” (Tellefsen has one of these, too.) Initially issued in a signed-and-numbered edition of 300, plus a metal version in an edition of just two, “Angela Rough” features a black-and-beige version of Beltrán’s Angela behind of grid of mud-red colored lines, like prison bars. According to ExpressoBeans.com, which has tracked 26 sales of “Angela Rough” over the last decade, the average resale price is about $250.

Yes, says Cushing, “Shepard Fairey did a rip-off poster of the Félix Beltrán poster. For people like Shepard Fairey and a younger generation of artists in all genres, it’s deemed okay to mash it out, to grab some things and re-interpret them. Well, it’s okay if you’re doing it as political work, but once you start doing it as fine art or as commercial work, that idea wears thin. This is where Shepard got into trouble. I think he just didn’t understand that what he was doing was a faux pas. But my main issue is not as much about artistic compensation as it is about the historical record.”

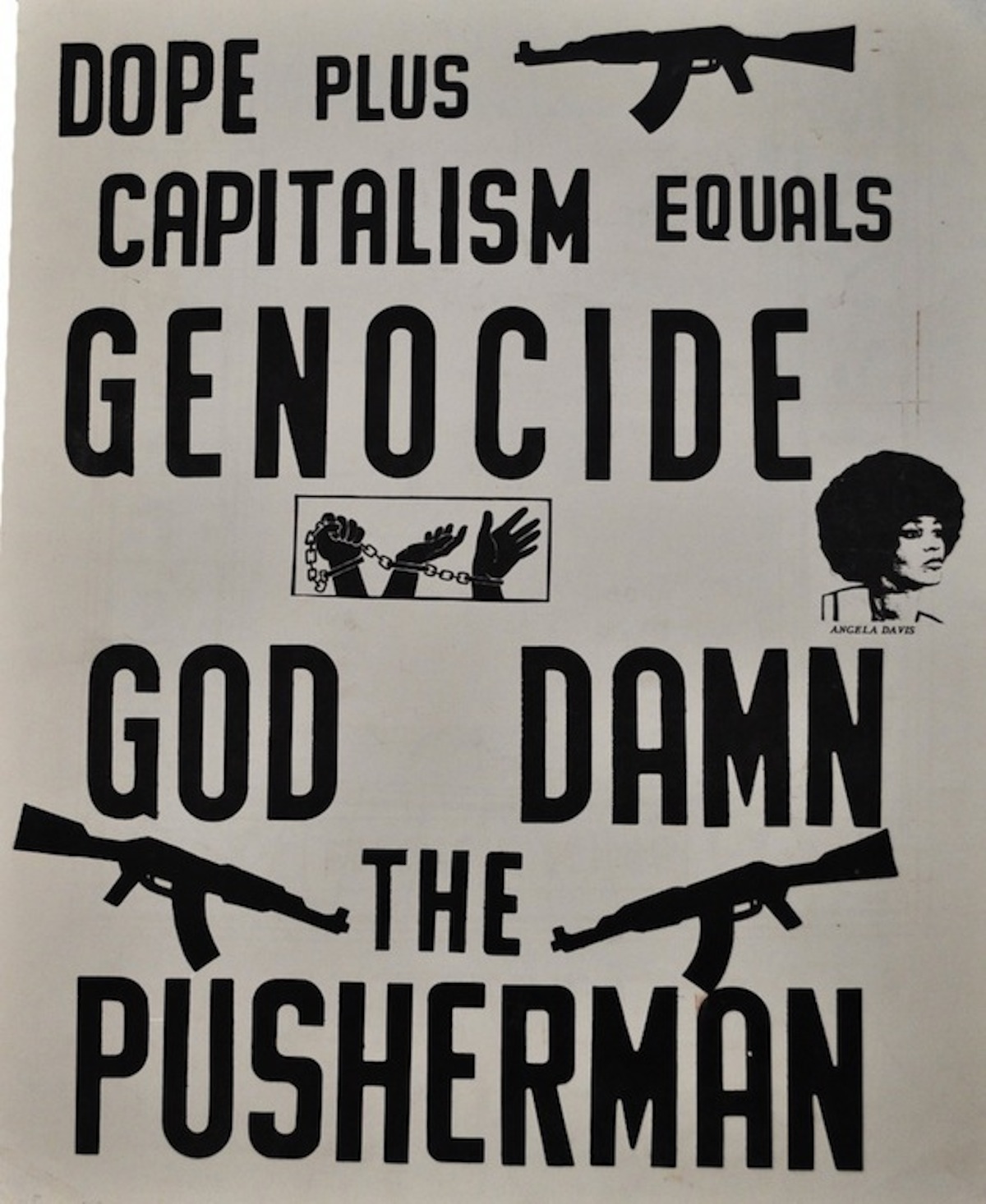

Davis’s image was sometimes used to signal the poster-maker’s allegiances. In this anti-drug, anti-capitalism poster, the hands in chains symbolize the Soledad Brothers.

Davis’s image was sometimes used to signal the poster-maker’s allegiances. In this anti-drug, anti-capitalism poster, the hands in chains symbolize the Soledad Brothers.

And how, you might wonder, does Angela Davis feel about all this? Well, despite repeated attempts, I was never able to speak with her, which means that like the provenance of my Angela Davis poster by Félix Beltrán, I may have to settle for hearsay evidence.

“I talked to her briefly once,” says Cushing. “I think she feels both proud and shrugs her shoulders at the idea of something that’s taken on a life of its own. She was a political activist and she was in the limelight, so I think she must have been pretty aware of the role her image and the media could play in promoting the values of both the Communist Party and the Panthers. At the time, that was part of the deal. For 15 years, there was no other ‘Angela.’ She really did become an icon, which was both a burden and a blessing. But I think she’s proud that her role led to the perpetuation of the movement’s spirit.”

Posters of Angela such as this one were designed, in part, to deliver the message that black is beautiful.

Besides, what Angela represented, even when it came to her freedom, was never just about her. At her behest, the phrase on her posters evolved from “Free Angela Davis” to “Free Angela Davis and All Political Prisoners.”

Tellefsen agrees. “The one consistent thing I’ve always heard her say is ‘this is really not about me’. The victory was really that such a broad coalition of people, who might not have been able to come together on almost any other basis, were able to successfully build a campaign that freed her. She was the lightning rod, but her victory was just the first step, hopefully.”

Angela Davis waves to someone in the audience as she arrives the room in San Rafael, Calif. for another pre-trial hearing. At left is chief attorney, Howard Moore Jr of Atlanta. holding the door Miss Davis is Capt. Harvey Teague of the Marin County Sherriffs Department

Angela Davis, San Rafael, USA. June 28, 1971

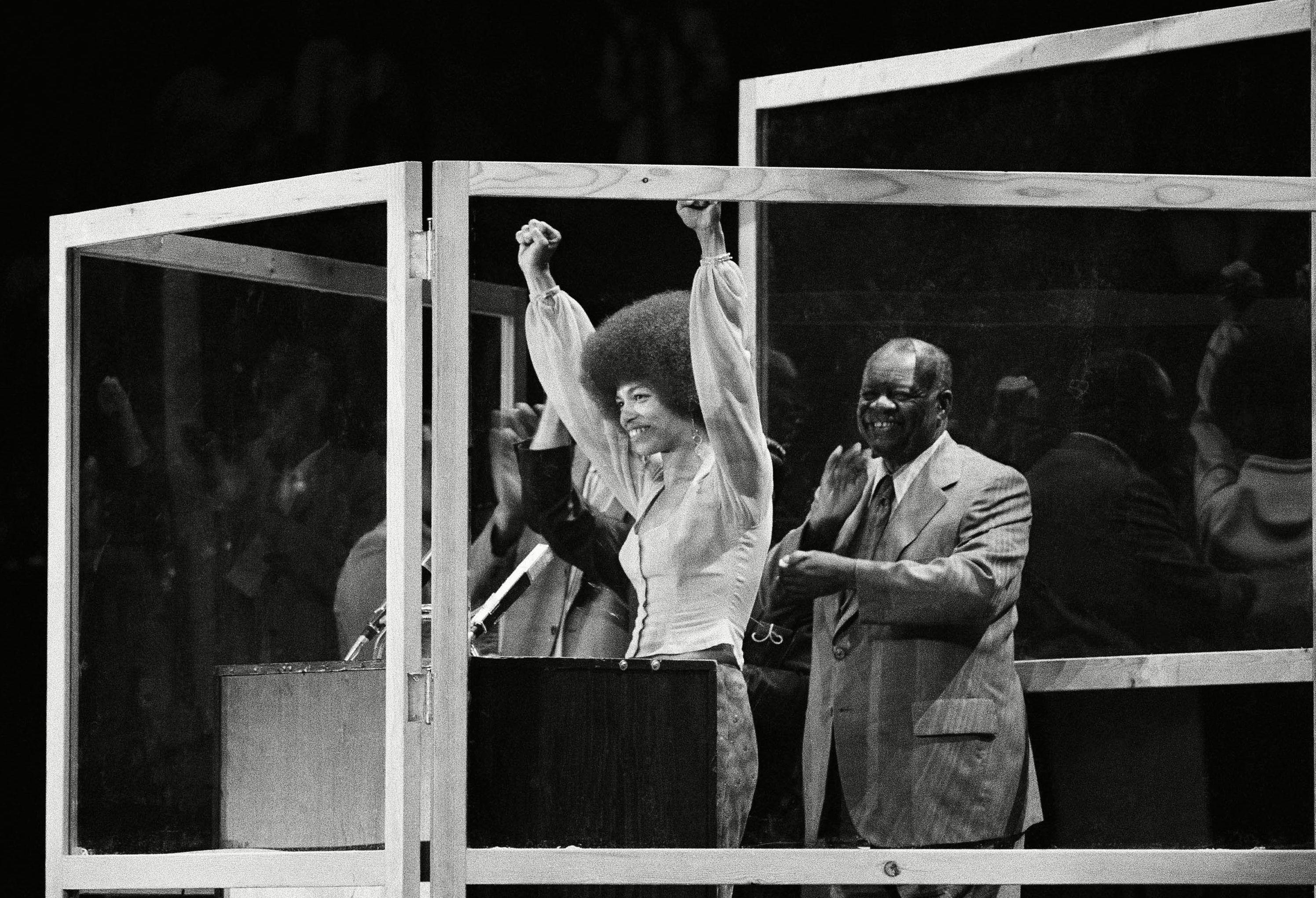

Angela Davis raises her arms in greetings after being introduced by Henry Wins right, to the audience at “An evening with Angela Davis” benefit at New York’s Madison Square Garden . They are standing in a special bullet-proof four-sided clear plastic booth which was set in place on the Garden’s stage for Davis’ speech

28 Jun 1972

(Special thanks to Lisbet Tellefsen for letting us photograph a small portion of her vast collection.)

Read more from Ben at Collectors Weekly. We recommend: Hippie Daredevils, Psychedelic Rock Posters and When Pianos Fell From the Sky.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.