The history of Soviet countercultures has been a subject of some fascination for Westerners. Much has been made, in some circles, of the 2008 Russian musical Stilyagi, which captures the lives and loves of Soviet hipsters in the 50s who listen to smuggled American rockabilly and jazz, comb their hair into pompadours, and pick up Elvis’s dance moves. Other fascinating artifacts circulating online include images of bootleg records made from discarded X-rays. Called roentgenizdat (X-ray press), the albums were a means of copying music using materials ready to hand, but their macabre appearance, surely, only added to the appeal.

By the mid-80s, the situation was much changed for Soviet youth. Gorbechev’s announcement in 1985 of the new era of perestroika and glasnost meant that young rockers began to have somewhat easier access to cultural products from abroad. And some sensed more radical shifts on the horizon. On the scene in Moscow and Leningrad at the time, photographer Igor Mukhin took it upon himself to document “the birth of a subculture unlike any other—that of the 1980s radical underground Soviet Rock movement,” writes Alice Nicolov at Dazed.

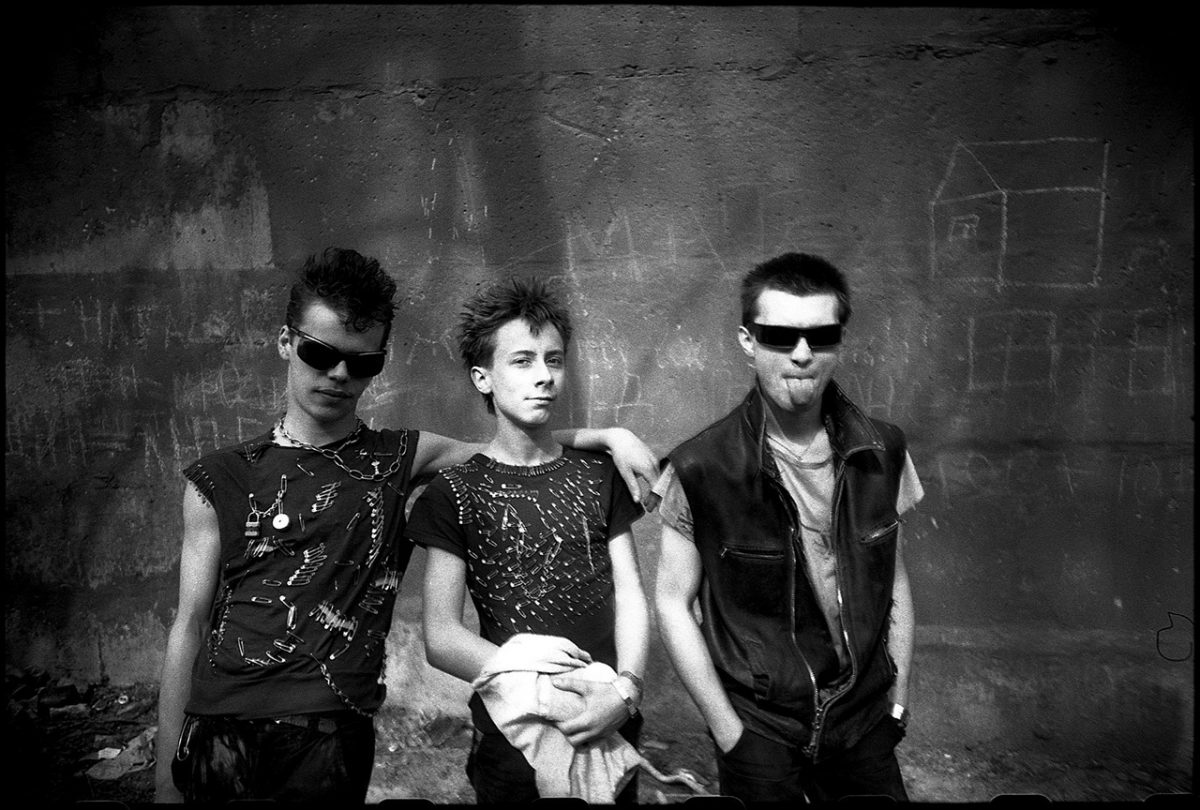

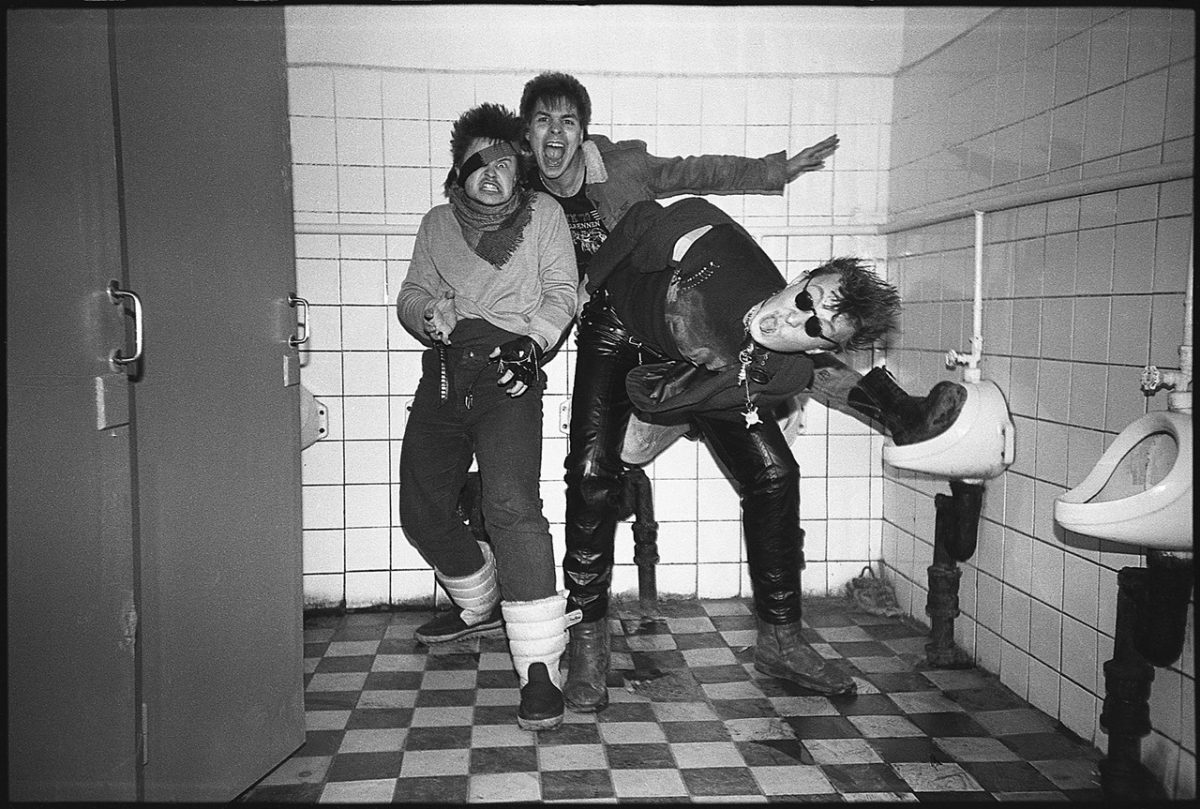

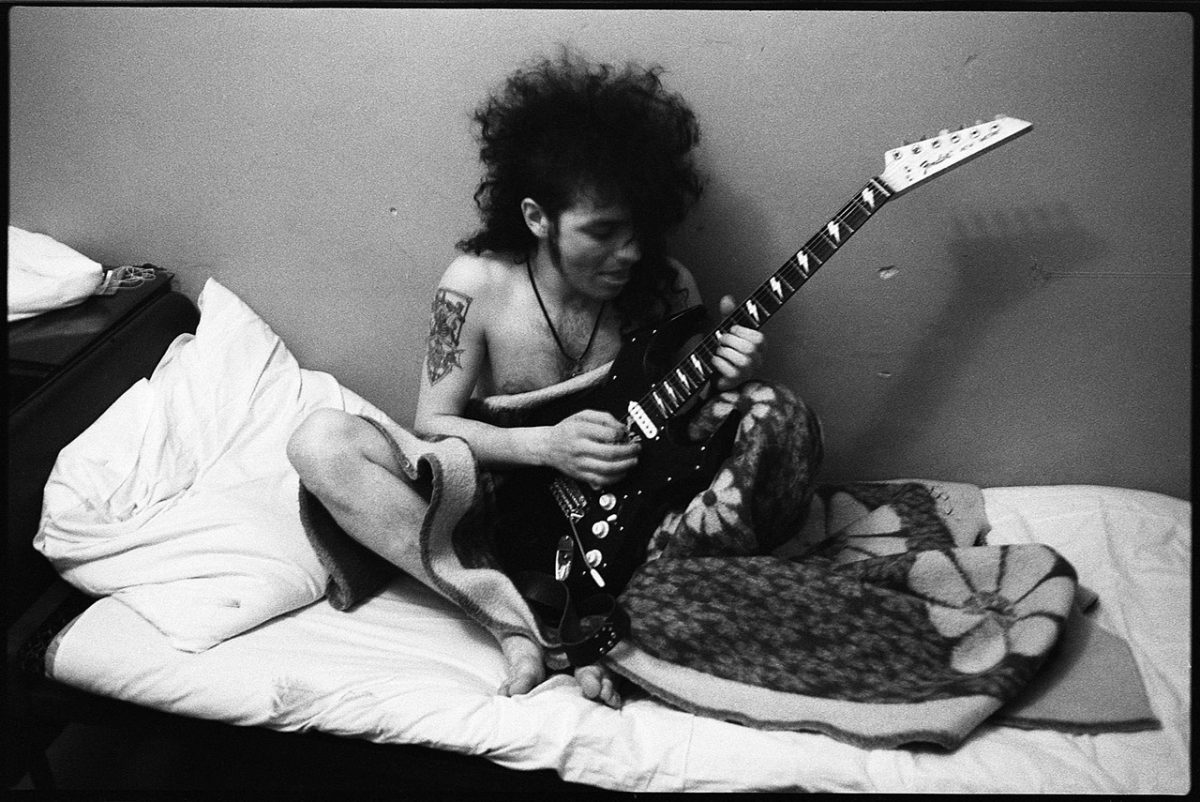

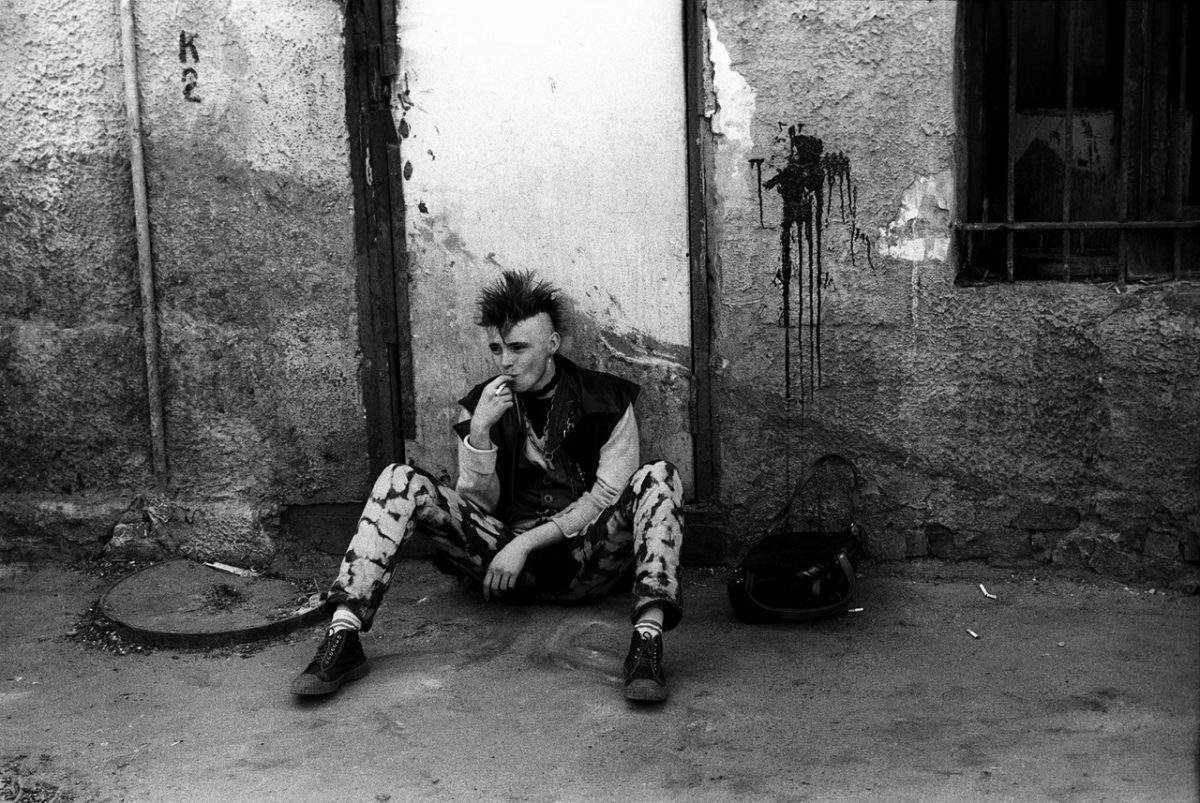

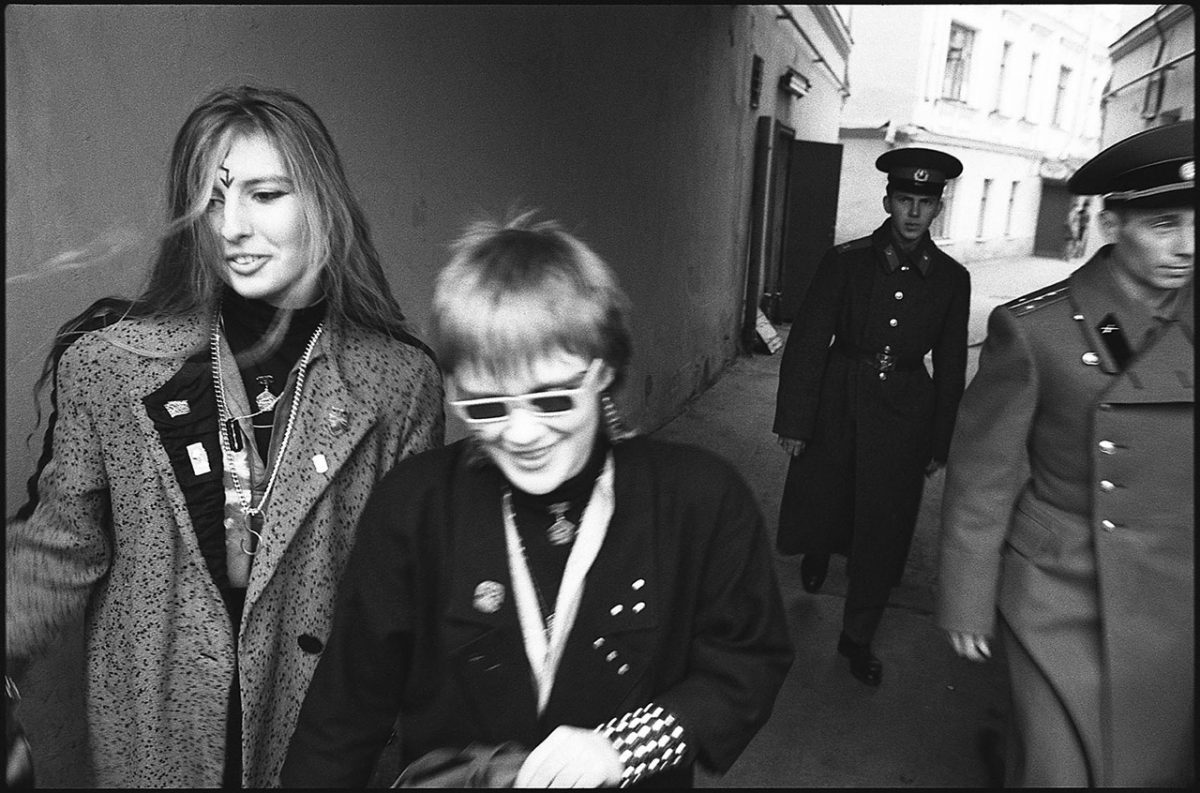

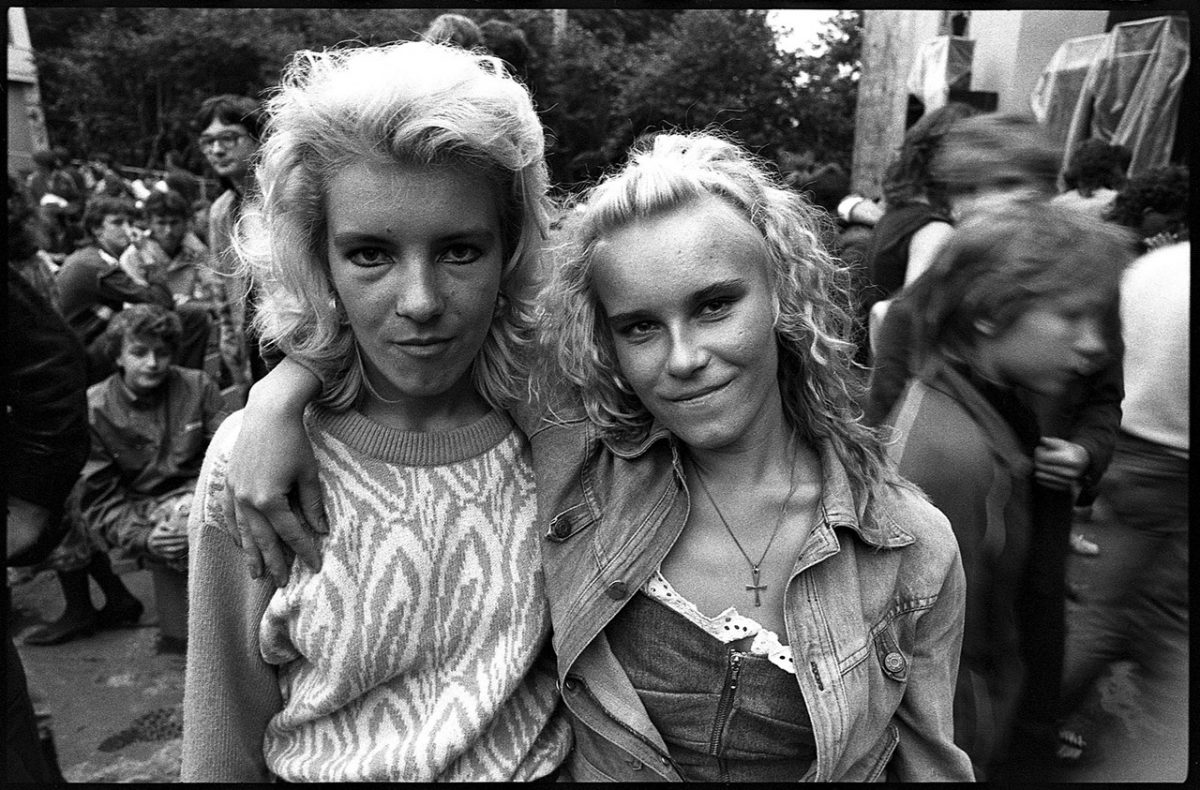

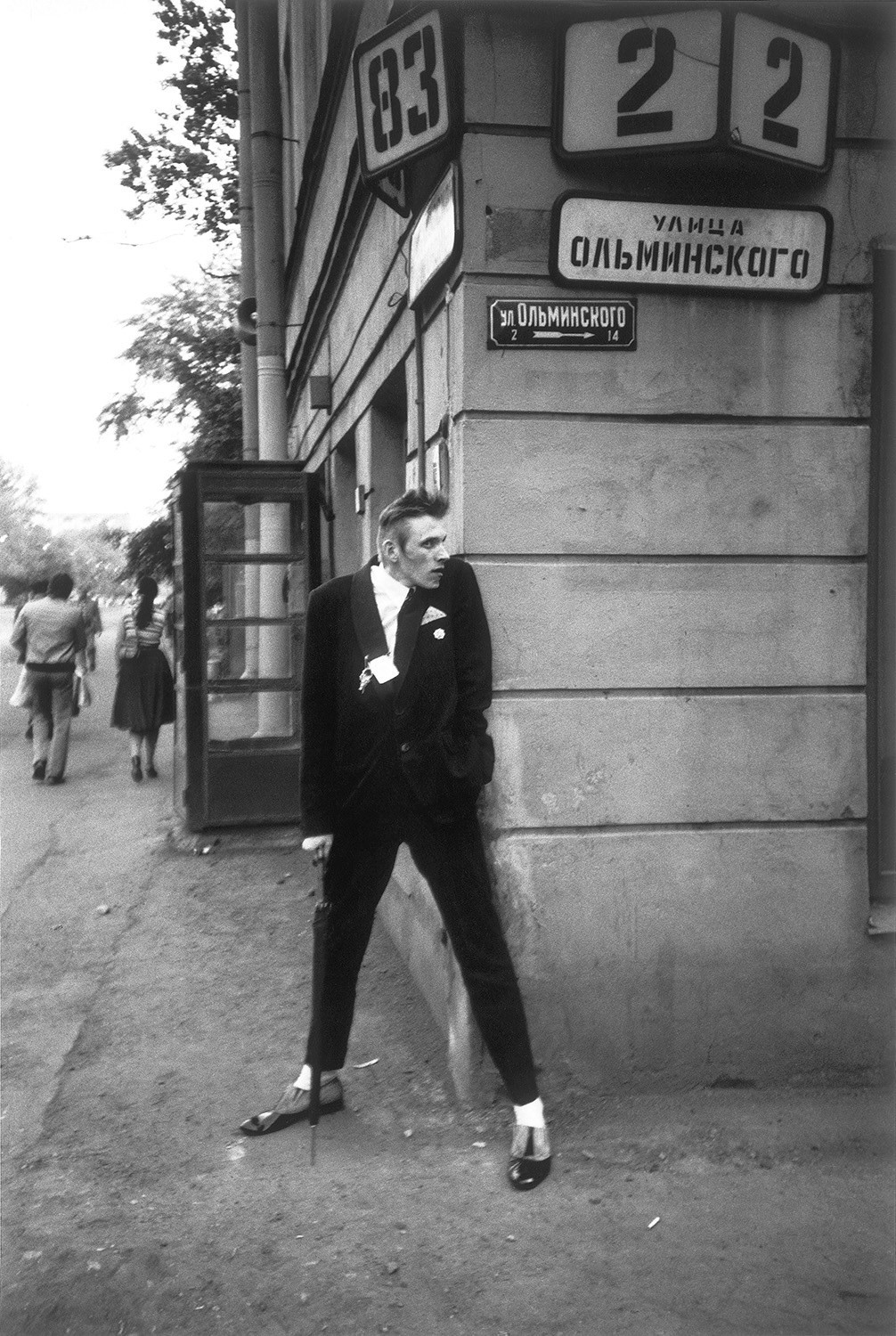

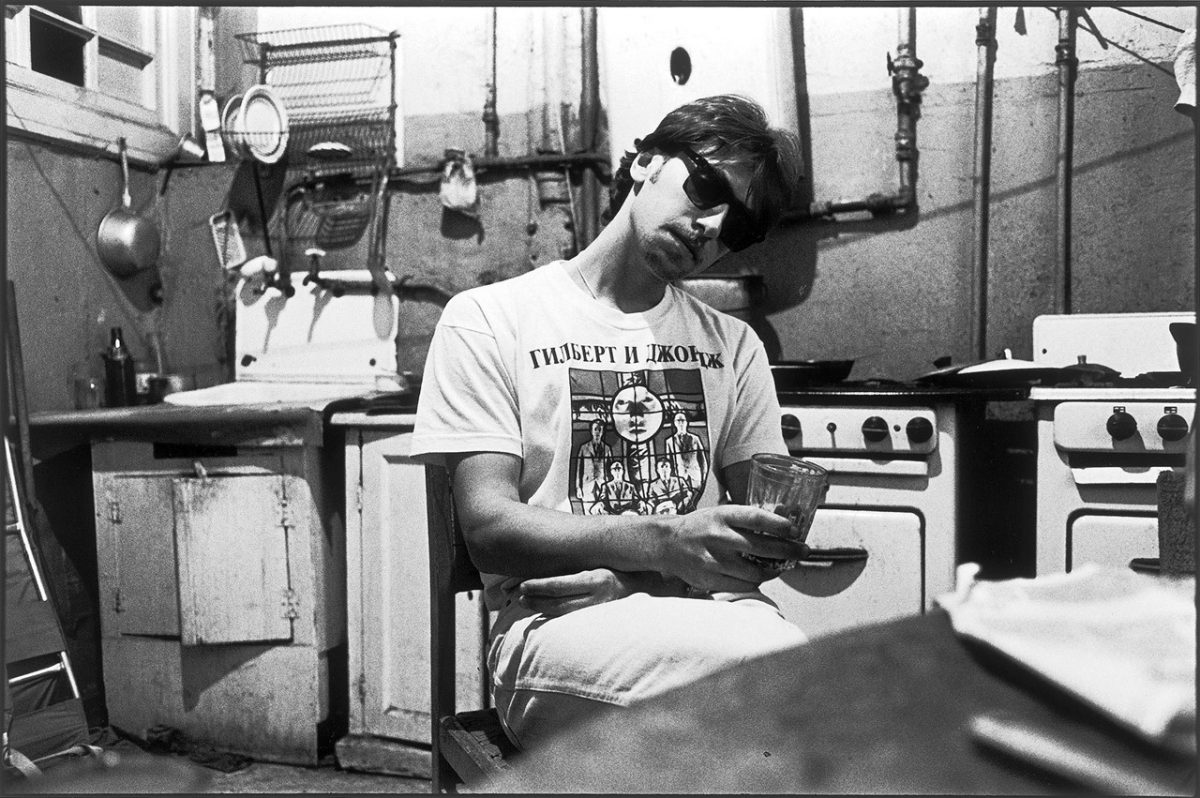

This was a time when Soviet youth couldn’t travel to the West or legitimately participate in a music scene operating outside of state control, but as the state apparatus loosened up they felt change coming and reacted. As a young photographer living through that time, Mukhin felt compelled to document the cultural explosion that he was himself a part of. His collection of striking black and white pictures of Leningrad rockers like Viktor Tsoi and Moscow kids in leather jackets studded with badges, incongruous against the stark background of Soviet architecture, tell the story of a forgotten period of Soviet history.

Mukhin talks about how Soviet rock subcultures developed in isolation from much of the world. “In the middle of the 80s,” he says, “I found myself a witness to the tremendous changes taking place in the USSR. At the time, we had no idea how the world looked beyond the Iron Curtain. We watched edited films in theaters; we picked up glitchy rock-n-roll on the radio through Voice of America or the BBC. It was impossible to see contemporary photography in the Soviet Union’s lone photo magazine, Soviet Photo. But I felt that the time of ‘change’ had come, and I needed to go and shoot.”

He’s since published these extraordinary documents in several rock and photography magazines and a book titled I’ve Seen Rock ‘n’ Roll. At the same time as the musicians and fans Mukhin photographed embraced the symbols of rock rebellion, “many people who lived through the era,” writes Sasha Raspopina, “say they never imagined that the end of their country was so close. They thought that guitar music, American jeans, and relaxed attitdues were as much freedom as they were ever going to get, so they made sure to take full advantage of it.”

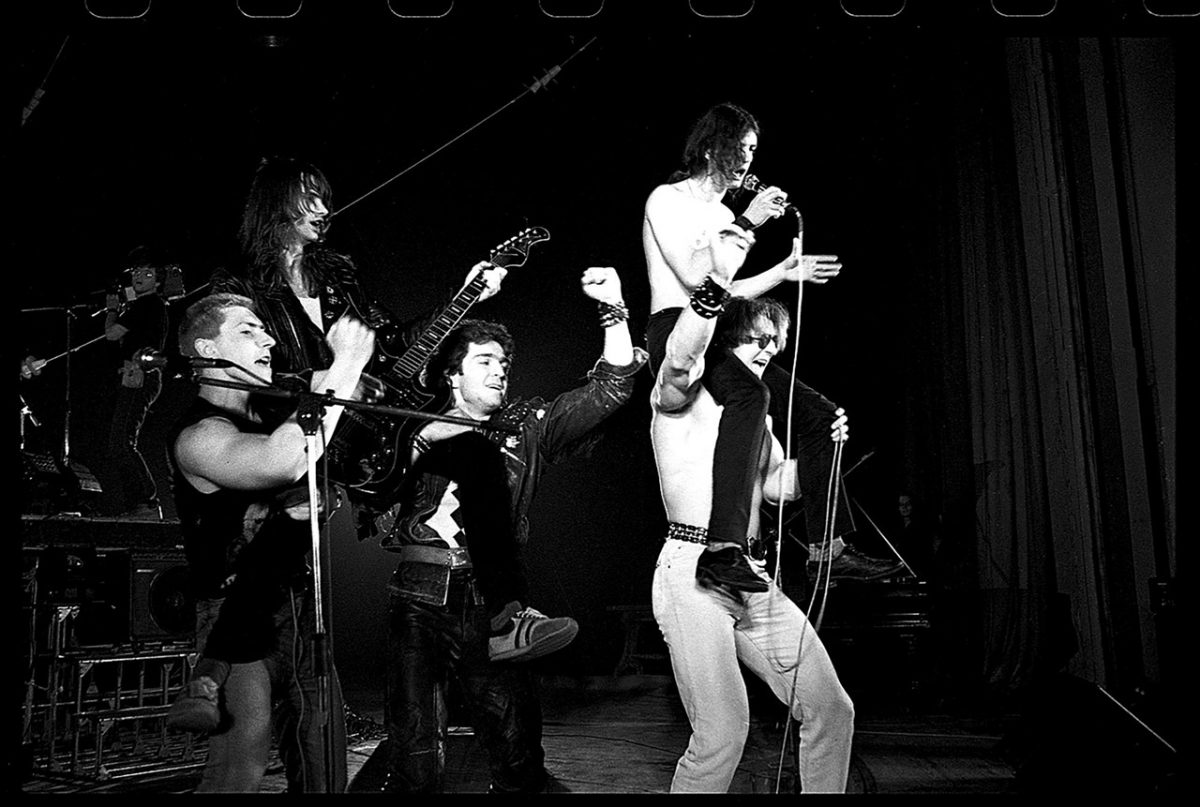

Mukhin himself, who had listened to Pink Floyd and Nazareth in the seventies, felt “drawn to our native rock,” including bands like Kino, Stranniye Igry, Advarium, Zvuki Mu, who performed at the Leningrad Rock Club and were part of the culture of samizdat books and magazines and illegally disseminated music. Mukhin describes the scene in the terms you’ll find used in talk about nearly every youth subculture around the world—a tight-knit group in which everyone practically knew everyone else.

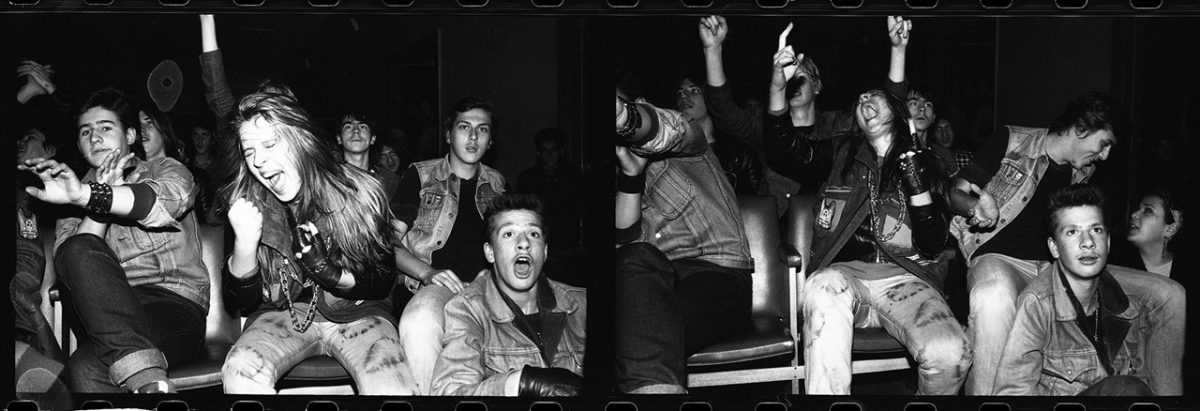

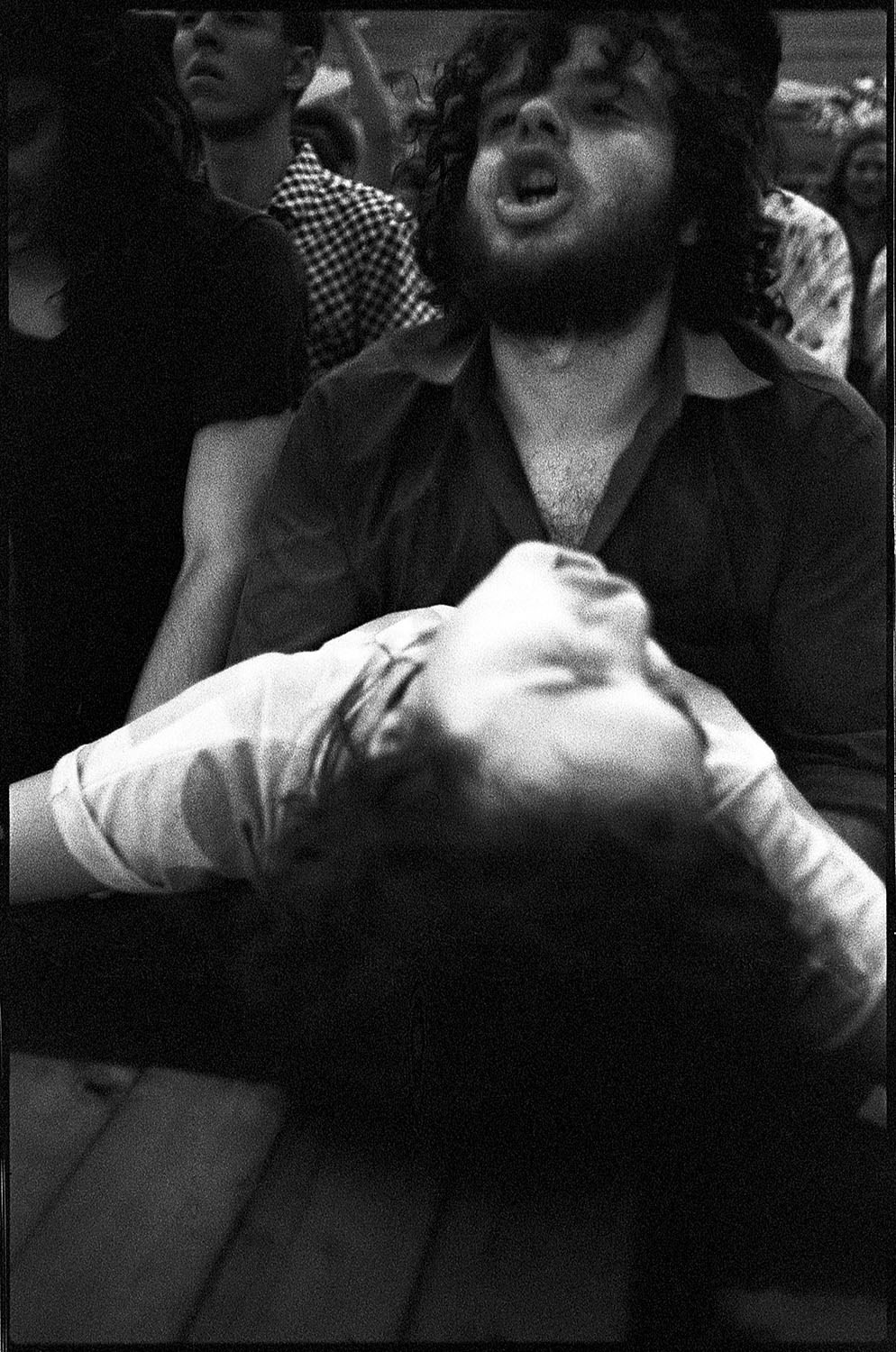

But his description of the critical difference between “official concerts” and the house parties and underground shows he captured is striking. “At official concerts,” he tells Nicolov, “it was forbidden to get up and move around, to stand up, to shout—all the things you want to do at a concert! At the most you were just allowed to sit down, listen and clap your hands. It was a totally different atmosphere at the underground concerts—people danced, they were relaxed.” You can see that joy and release of pent-up energy on the faces of Mukhin’s punks and metalheads (so often surrounded by symbols of the old order): the expectation of change and reveling in the new, if limited, freedom to rock.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.