On May 24, 2011 Huguette Clark died in the New York hospital rooms where she’d lived for 20 years, often under the name Harriet Chase. She was 104.

She left behind musuems of her age, vast homes dripping in oppulence and exquisite taste; mansions she had had maintained but not set foot in for decades.

Clark had not stepped inside any of her sprawling homes for years: the 42-room apartment on Fifth Avenue; a 23-acre property, with a 21,666-square-foot French mansion high on a mesa above Santa Barbara’s East Beach; and a country manor in New Canaan, Conn. The places were well maintained thoughout her period of self-imposed exile, when she was hermitcally sealed in the medical centres.

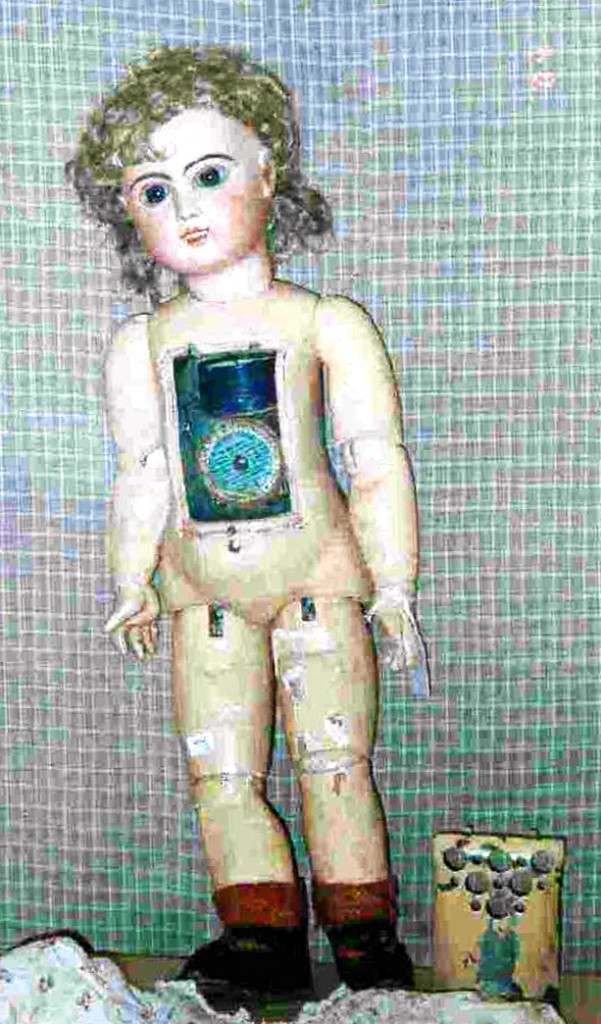

She had all she needed in her quarters at the Beth Israel Medical Center. She was cared for by a myriad staff and surrounded by her collection of unsettling fine china dolls. She was cared for. Others looked after her fortune.

Born on June 9, 1906, in Paris, France, Huguette Marcelle Clark was a daughter of William Andrews Clark, a man with an American story of his own. Born in 1839 to a dirt pooor Pennsylvania family, the young man had journeyed to the Montana Territory, where he mined. And sometime in the 1870s, he struck copper. His fortune was made.

Back then Montana was another country:

The discovery of gold brought many prospectors into the area in the 1860’s, and Montana became a territory in 1864. The rapid influx of people led to boomtowns that grew rapidly and declined just as quickly when the gold ran out.

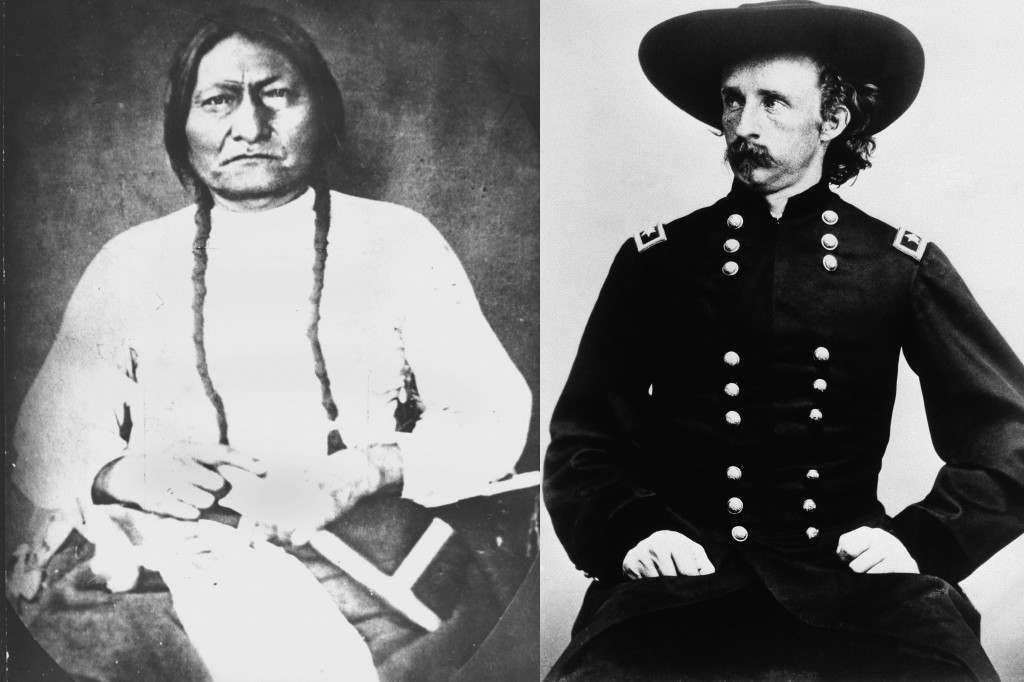

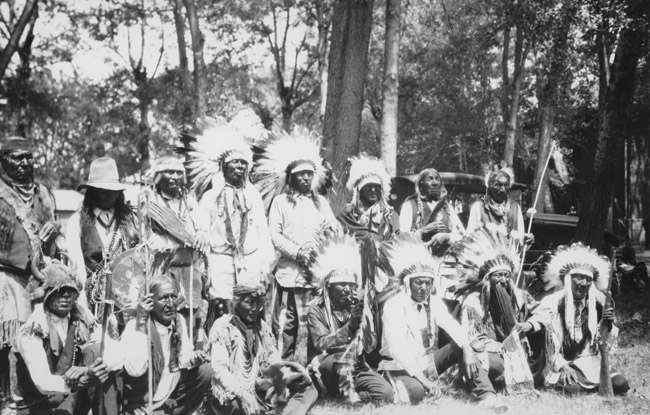

As more and more white people came into the area, Indians lost access to their traditional hunting grounds and conflicts grew. The Sioux and Cheyenne were victorious in 1876 at the Battle of the Little Bighorn, and Chief Joseph and the Nez Perce won a battle in the Big Hole Basin (1877). Yet, in the end, the Indians could not hold out against the strength of the United States army.

Little Big Horn Battle Survivors, Cheyenne Tsistsistas (via)

Miners weren’t the only early settlers in Montana. Cattle ranches began flourishing in western valleys during the 1860’s as demand for beef in the new mining communities increased. After 1870 open-range cattle operations spread across the high plains, taking advantage of the free public-domain land.

During the 1880’s railroads crossed Montana, and the territory became a state in 1889.

He then set about securing political influence. As the New York Times tells it:

In the late 1890s, desiring a Senate seat, Mr. Clark went out and bought one, at least temporarily. By this time Montana was a state; under the United States Constitution, senators of the period were elected by their state legislatures. Mr. Clark, a Democrat, was reported to have loosed a cataract of thousand-dollar bills on the Montana statehouse, to no small effect. He took up his Senate seat in December 1899.

He vacated the seat in May 1900 as the Senate weighed a resolution to void his election. Later returned to office by the legislature, he served one term, from 1901 to 1907.

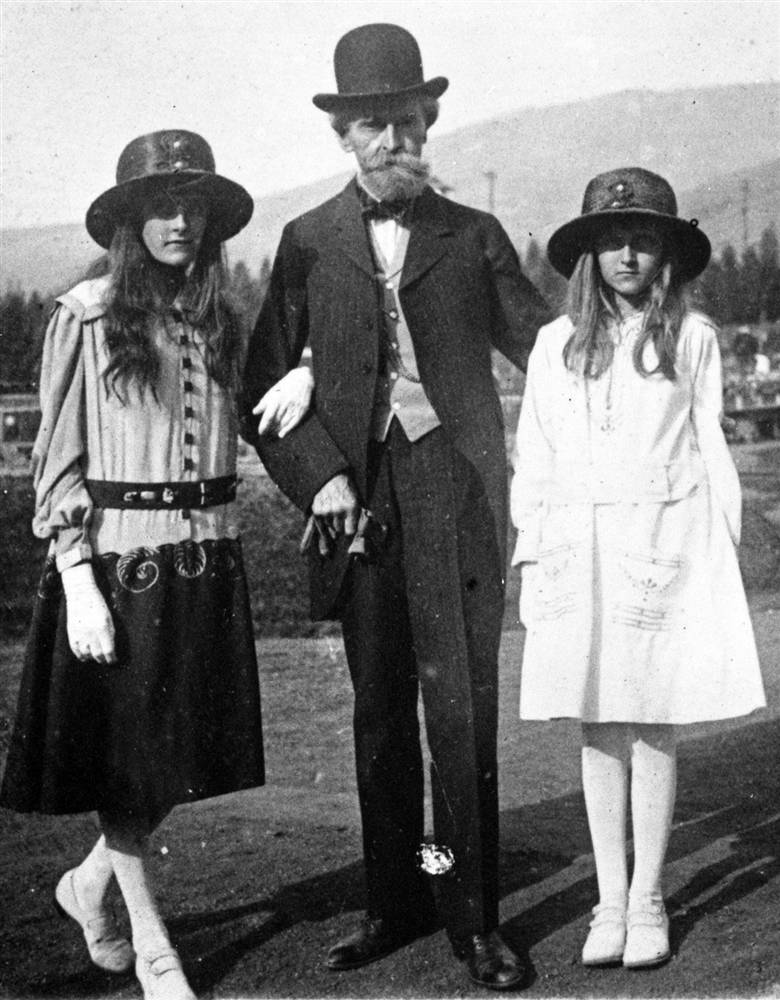

After the death of 16-year-old daughter Andrée Clark from meningitis in 1919, W.A. Clark gives the deed to land for the first national girl scout camp, Camp Andrée Clark, in New York. Huguette Clark, 13, stands with her father.

By this time, Senator Clark was one of the richest men in America. In 1907, The New York Times estimated his fortune at $150 million — roughly $3 billion today. Besides copper, his interests included railroads, real estate, lumber, banking, cattle, sugar beets and gold.

He was a man of obvious tastes. After all, he was one of the founders of Las Vegas, delivering people and commerce when he chose the town as the intersection for two of his railroads.

His first wife bore five children, four of whom lived to adulthood. After her death in 1893, he took up with his teenage ward, Anna La Chapelle

W.A. and Anna Clark, Huguette’s parents, in the old Clark Mansion on Fifth Avenue. This room is said to be Anna’s bedroom.

They apparently married in 1901 and had two daughters, Andrée, born in 1902, and Huguette, born in Paris on June 9, 1906.

At Huguette’s birth, her mother was 28, her father 67.

Montana was never going to be enough for Clark, and the family moved to New York, where he built a 121-room (31 batchrooms; four art galleries; just one theater) bijou home at 962 Fifth Avenue and 77th Street.

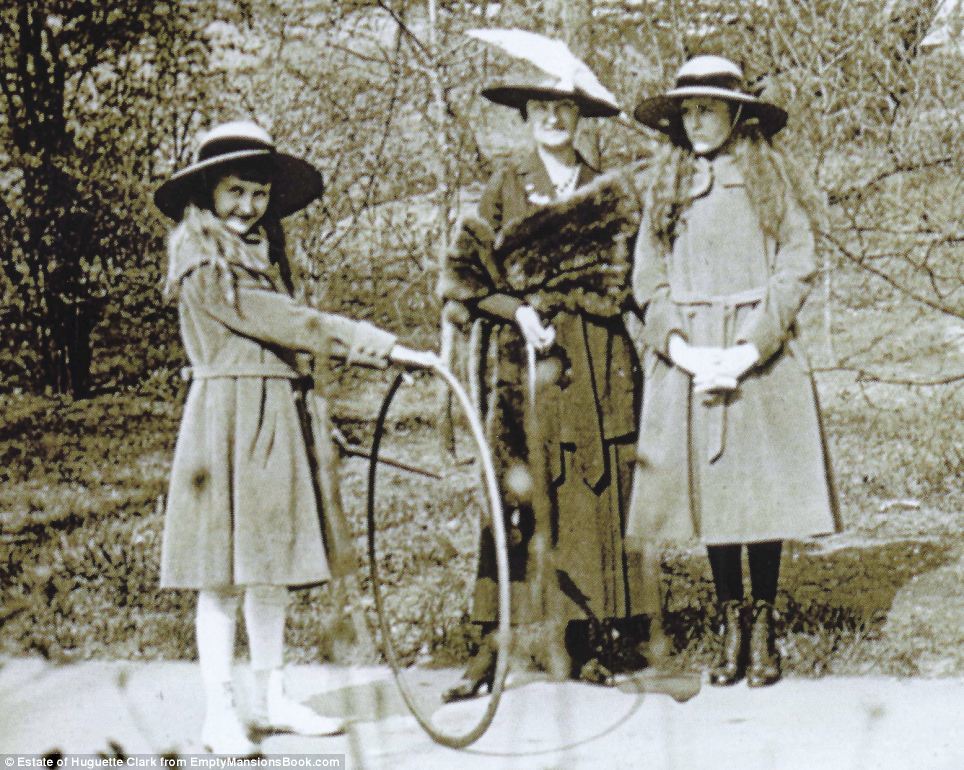

Clark with his daughters Huguette Clark (right) and Andrée (left) c. 1917

Donated to the Montana Historical Society in 1969

In 1919, Andrée Clark, Huguette’s sister, died of meningitis at 16; by all accounts her death shook Huguette deeply.

lark is pictured left with her sister, Andree, who passed away when she was a teenager, and their mother, Anna

Senator Clark died in 1925; many of the masterworks he owned now make up the William A. Clark Collection at the Corcoran Gallery of Art in Washington.

Huguette Clark, second from left, in her graduating class of 1925 from Miss Spence’s Boarding and Day School for Girls, New York.

Huguette graduated from Miss Spence’s School (now the Spence School) in Manhattan and was introduced to society in 1926. Not long after her father’s death, she and her mother moved to an elegant apartment building at 907 Fifth Avenue, at 72nd Street.

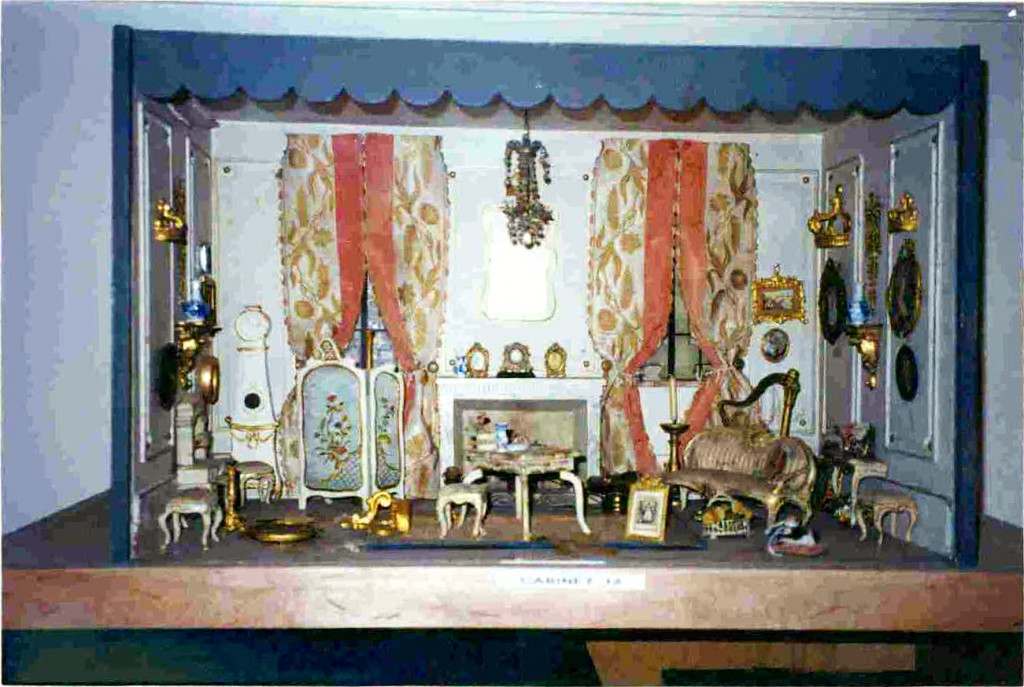

Her dolls came, too:

Dollhouse furniture and accessories, organized on shelves in Huguette Clark’s Fifth Avenue apartments. Taken from snapshots among her personal papers.

Dollhouse furniture and accessories, organized on shelves in Huguette Clark’s Fifth Avenue apartments. Taken from snapshots among her personal papers.

On May 18, 1993, Huguette was a bidder at a Sothebys auction for two antique French dolls. The first, in Lot 219, was a Jumeau triste pressed bisque doll, circa 1875, with a dimple in the chin, fi xed brown glass paperweight eyes, pierced ears, blond mohair wig, in cream lacy overdress with Eau-de-Nil silk below and cream lacy and silk bonnet. The estimate was $12,000 to $15,000. She authorized her attorney to bid up to $45,000, but got it for $14,933.

And her fabulous jewels:

An art deco diamond and multi-gem charm bracelet with charms, by Cartier, circa 1925. Sale price in 2012, $75,000. All these items found in Huguette Clark’s safe deposit box were auctioned on April 17, 2012, by Christie’s New York.

A pair of emerald, natural pearl and diamond ear pendants, by Cartier, early 20th century. Sale price in 2012, $85,000. All these items found in Huguette Clark’s safe deposit box were auctioned on April 17, 2012, by Christie’s New York.

Upon his death, Huguette inherited one fifth of her father’s fortune.

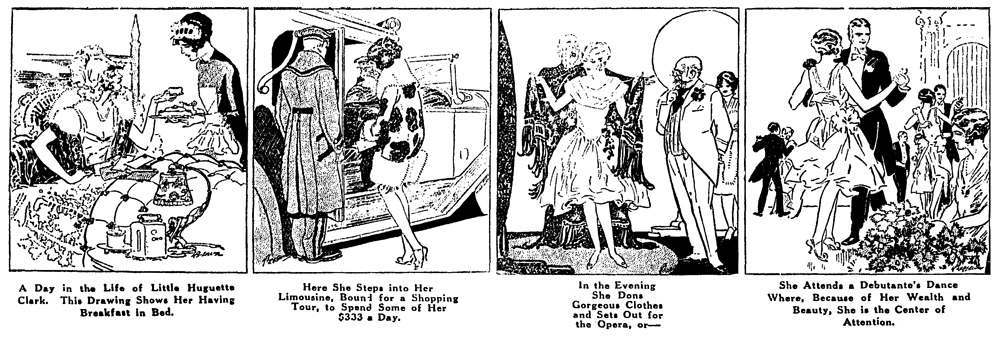

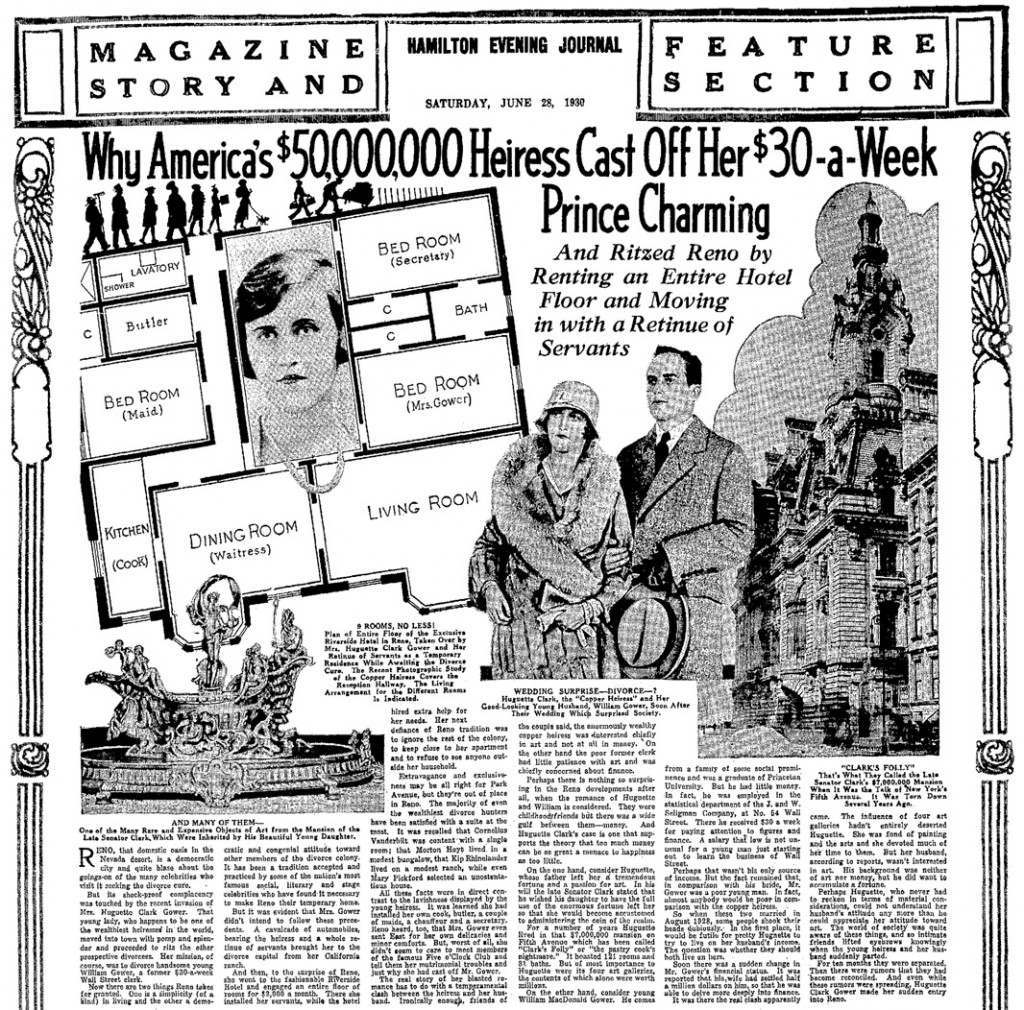

Little Huguette was quite a catch:

In 1928, at 22, she married William MacDonald Gower, the son of a business associate of her father’s. The union lasted nine months: she charged desertion; he maintained the marriage was unconsummated, according to a 1941 biography of the family, “The Clarks, an American Phenomenon,” by William D. Mangam.

The couple were formally divorced in 1930; she chose to be known afterward as Mrs. Huguette Clark.

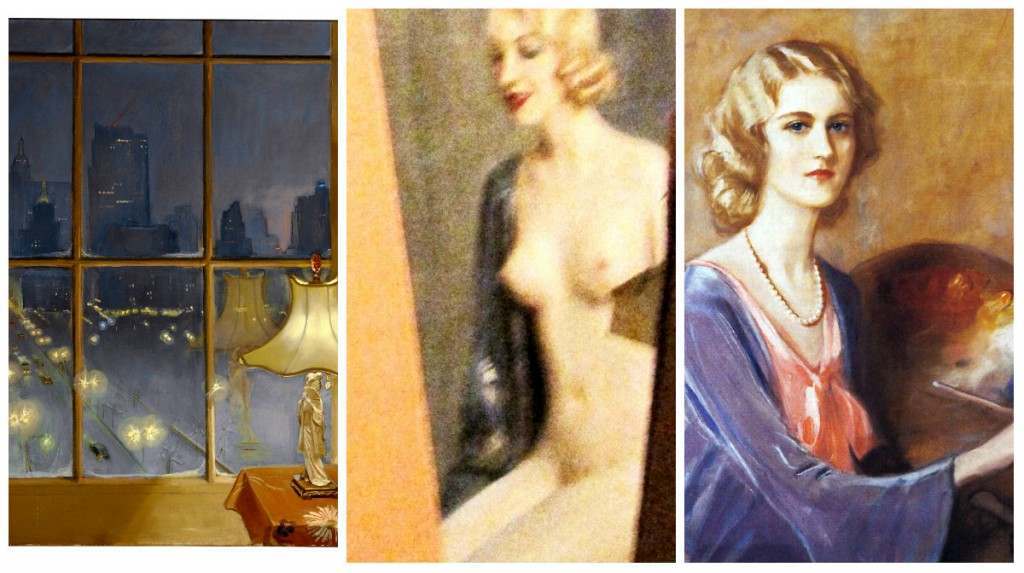

By the late 1930s, Mrs. Clark was living with her mother at 907 Fifth Avenue. She painted and posed:

When Huguette inherited Bellosguardo from her mother in 1963, she gave the staff two instructions: Everything was to be kept in “first-class condition,” and nothing was to change. Time stood still.

For the quarter-century that followed, Mrs. Clark lived in the apartment in near solitude, amid a profusion of dollhouses and their occupants. She ate austere lunches of crackers and sardines and watched television, most avidly “The Flintstones.” A housekeeper kept the dolls’ dresses impeccably ironed.

And one day she went to hospital. She’s wasn’t ill.

And her homes remained empty. Bill Dedman heard the story of the American heriess and wanted to find out more. He went to Belloisguardo. And he went inside. He reported what he found to NBC:

Up close, Bellosguardo appears to be in pristine condition. The only residents during these decades have been the estate manager, his dogs, and a tame family of foxes. As we arrive, a fox is at work by the reflecting pool and the grove of 80-year-old orange trees, hunting in the sun for lizards.

Inside the great house, there is a touch of the eccentric: In Huguette’s dressing room, the covered chairs come in two sizes: full-sized ones for adults, and tiny, half-height chairs for her collection of French and Japanese dolls.

And out in the whitewashed carriage house, automobiles sit unused: a 1933 Chrysler Royal Eight convertible and an enormous black 1933 Cadillac seven-passenger limousine, both with California plates dated 1949.

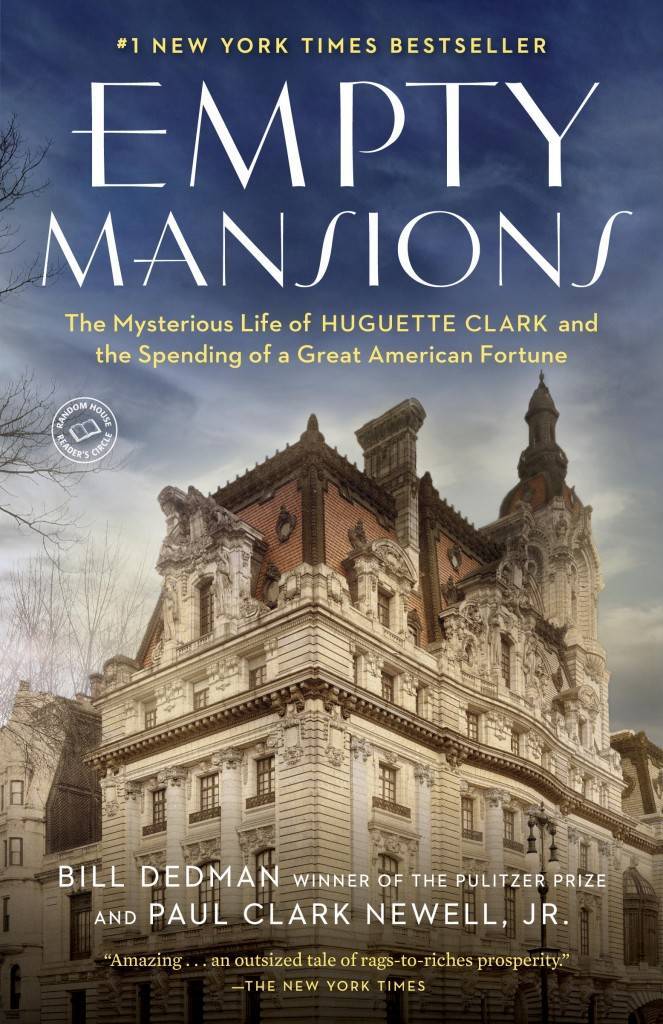

You can read the fascinating story in Empty Mansions: The Mysterious Life of Huguette Clark and the Spending of a Great American Fortune.

The No.1 bestselling book “Empty Mansions: The Mysterious Life of Huguette Clark and the Spending of a Great American Fortune” By Bill Dedman and Paul Clark Newell, Jr. This is the paperback edition.

Now it’s time to look around. Many of the photots (the black and white picures) are from 1940:

Bellosguardo, Santa Barbara

Bellosguardo, the Clark estate in Santa Barbara, California. At the top of the photo is the Andrée Clark bird refuge, which Huguette Clark paid for in 1928 as a memorial to her sister. Cabrillo Boulevard snakes between the bird refuge and the Clark property. The front driveway rises alongside the bluff and makes a hairpin turn in front of the house. At center right is the circular rose garden. At the upper right, with the red roof, is the estate manager’s house. No one from the immediate family has visited since the early 1950s.

The library at Bellosguardo, the Clark summer home in Santa Barbara, California, c. 1940. The hundreds of bound leather volumes include works by Dante, Goethe, Homer, Virgil, Maupassant, Dickens, Tennyson, Thackeray, Voltaire, Faust, Milton, Cervantes, Conrad. Although no one from the immediate family has visited since the early 1950s, the house man dusts and turns the books periodically.

The bedroom of Anna Clark, Huguette’s mother, at Bellosguardo, the Clark summer home in Santa Barbara, California, c. 1940. One of her French pedal harps sits at the foo of the bed. A painting by Sargent hangs between the windows. Photos of Anna’s husband, Sen. W.A. Clark, and their elder daughter, Andrée, are on display here. No one from the immediate family has visited Bellossince the early 1950s.

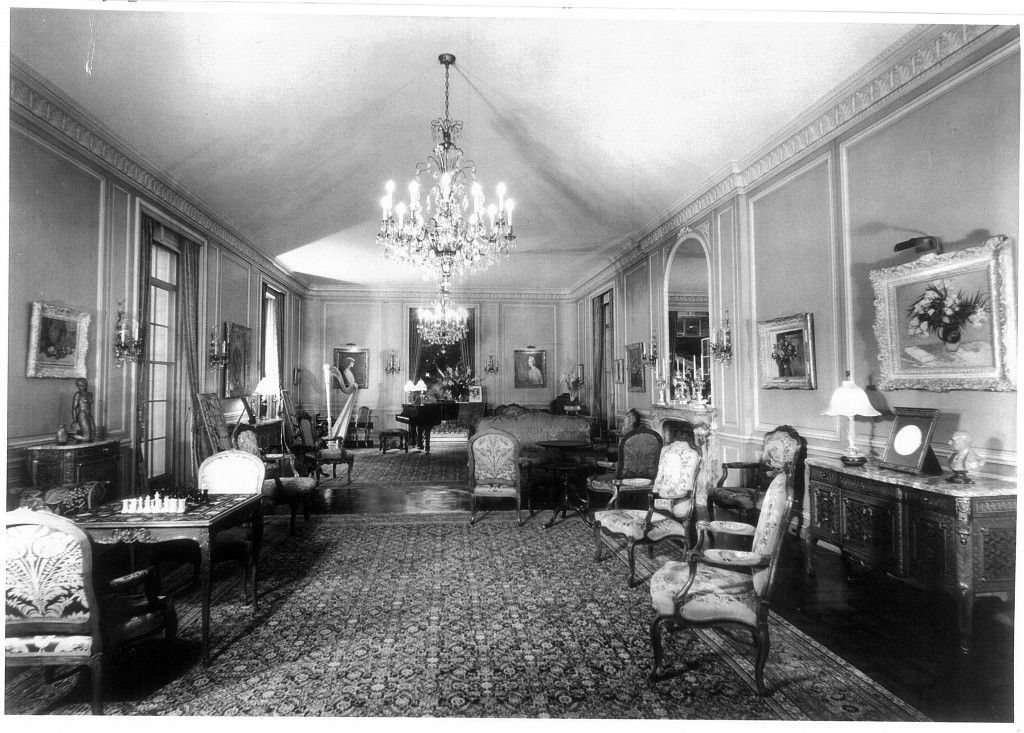

Portraits of the daughters by Tadé Styka flank a Steinway piano in the music room a Bellosguardo, the Clark summer home in Santa Barbara, California. One of their mother Anna Clark’s French pedal harps is at left. No one from the immediate family has visited since the early 1950s. this photo is from about 1940.

Anna Clark’s bedroom at Bellosguardo, the Clark summer home in Santa Barbara, California. Photos show Huguette’s sister, Andrée.

The circular powder room with curved doors on the main floor of Bellosguardo, the Clark summer home in Santa Barbara, California. This photo is from about 1940.

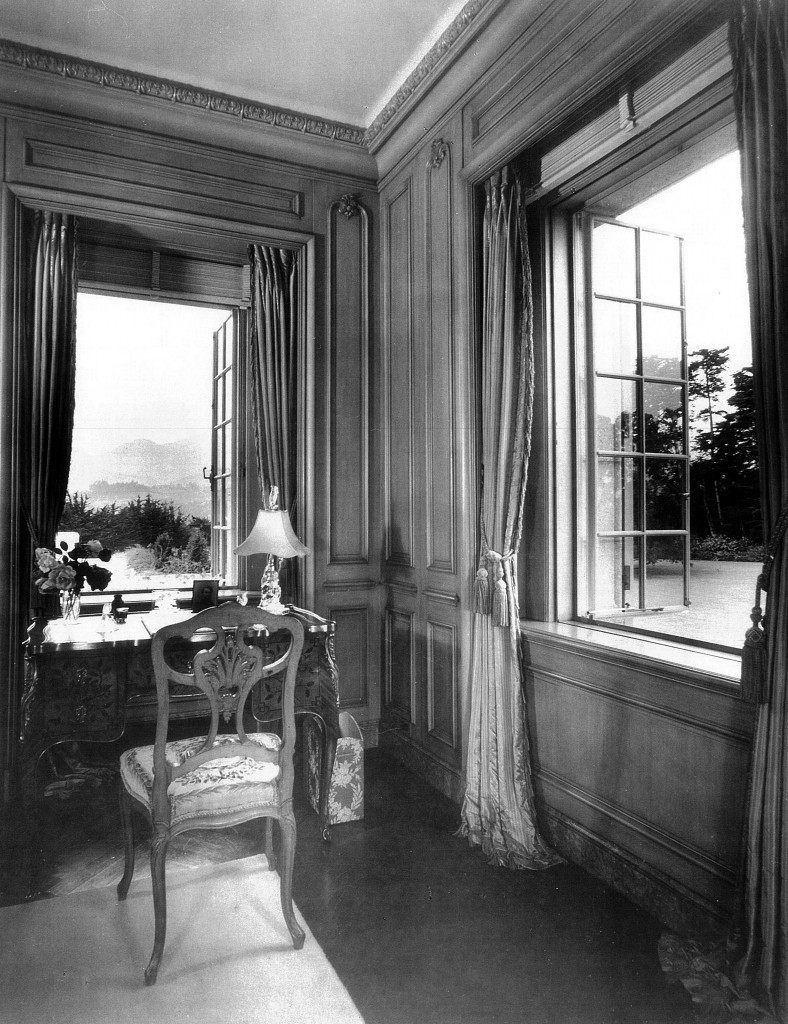

The view out to the Santa Ynez Mountains, c. 1940, from a bedroom at Bellosguardo, the Clark summer home in Santa Barbara, California.

Game tables are ready for chess and cards in the music room at Bellosguardo, the Clark summer home in Santa Barbara, California. Two paintings by Cézanne, a still life of an earthenware pitcher and a portrait of Madame Cézanne in red, hang on the left. On the right are paintings of flowers by Renoir and Van Gogh. At the far end are portraits of the daughters Andrée and Huguette, a Steinway piano, and one of Anna Clark’s French pedal harps. This photo is from about 1940.

A bathroom upstairs at Bellosguardo, the Clark summer home in Santa Barbara, California. This photo is from about 1940.

A 1933 Chrysler Royal Eight convertible inside the carriage house at Bellosguardo, the Huguette Clark estate in Santa Barbara, California.

Huguette’s Fifth Avenue Apartment

Inside Huguette Clark’s apartments at 907 Fifth Avenue, New York, after she died in 2011 at age 104. She lived the last 20 years of her life in a simple hospital room.

Inside Huguette Clark’s apartments at 907 Fifth Avenue, New York, after she died in 2011 at age 104. She lived the last 20 years of her life in a simple hospital room.

Inside Huguette Clark’s apartments at 907 Fifth Avenue, New York, after she died in 2011 at age 104. She lived the last 20 years of her life in a simple hospital room.

Le Beau Château, Connecticut

As her mother had bought a California ranch as a refuge during World War II, Huguette Clark during the Cold War bought this Connecticut retreat, Le Beau Château, in New Canaan. It sat empty for more than sixty years. When she offered it for sale, so she could bestow more gifts on her friends and staff, it led to the disclosure of her reclusive lifestyle.

A thermostat from the 1930s in Le Beau Château, Huguette Clarks country retreat on 52 acres in New Canaan, Connecticut, unlived in since 1951.

The Mosler safe that filled a closet at Le Beau Château, Huguette Clarks country retreat on 52 acres in New Canaan, Connecticut, unlived in since 1951. When it was opened recently in front of a gaggle of attorneys, all it contained was a set of plans for the addition Clark put on the house in 1952.

Huguette Clark’s bedroom in Le Beau Château, her country retreat on 52 acres in New Canaan, Connecticut, unlived in since 1951.

The spiral front staircase of Le Beau Château, Huguette Clarks country retreat on 52 acres in New Canaan, Connecticut, unlived in since 1951.

After her death, the lots were auctioned. NPR radio reported in 2014:

About the book:

“Empty Mansions” is a mystery of wealth and loss — and a secretive heiress named Huguette Clark. Though she owned palatial homes in New Canaan, Connecticut, and Santa Barbara, and three apartmnents totaling 42 rooms on Fifth Avenue, why had she lived for twenty years in a simple hospital room, despite being in excellent health? Empty Mansions unravels the story of her remarkable family, from the father, W.A. Clark, the copper king, founder of Las Vegas, and controversial U.S. senator, to his daughter, the generous artist who held a ticket on the Titanic and was still living in New York City on 9/11. Pulitzer Prize-winning investigative reporter Bill Dedman, who discovered Huguette’s story for NBC News, has collaborated with Huguette Clark’s cousin, Paul Clark Newell, Jr., one of the few relatives to have conversations with her. Dedman stumbled onto the story when he noticed Huguette’s New Canaan mansion for sale for $25 million, though it had been unfurnished since she bought it in 1951.

It’s living history from the Age of Innocence and experince.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.