The big Jean-Michel Basquiat show at London’s Barbican features artwork valued in the tens of millions of dollars. We know it’s worth a fortune because earlier this year Basquiat’s Untitled (1982) – an improvised painting of a livid-eyed, black skull scarred with hole-punch nostrils, bared teeth and red rivulets of blood over an azure blue wall of graffiti sum and letters – sold for $110.5m at auction. Basquiat’s no longer among us in blood and bone; his fortune is posthumous, gained long after he died from a heroin overdose in 1988 at the pop legend age of 27. And because a Japanese billionaire wants to spunk a stupendous amount of money owning something whose message and meaning surely escape him utterly, Basquiat: Boom for Real at the London’s Barbican is a big pull. But the raw artist whose style and exhilarating art made him a Down Town pet is more than a rich man’s hobby.

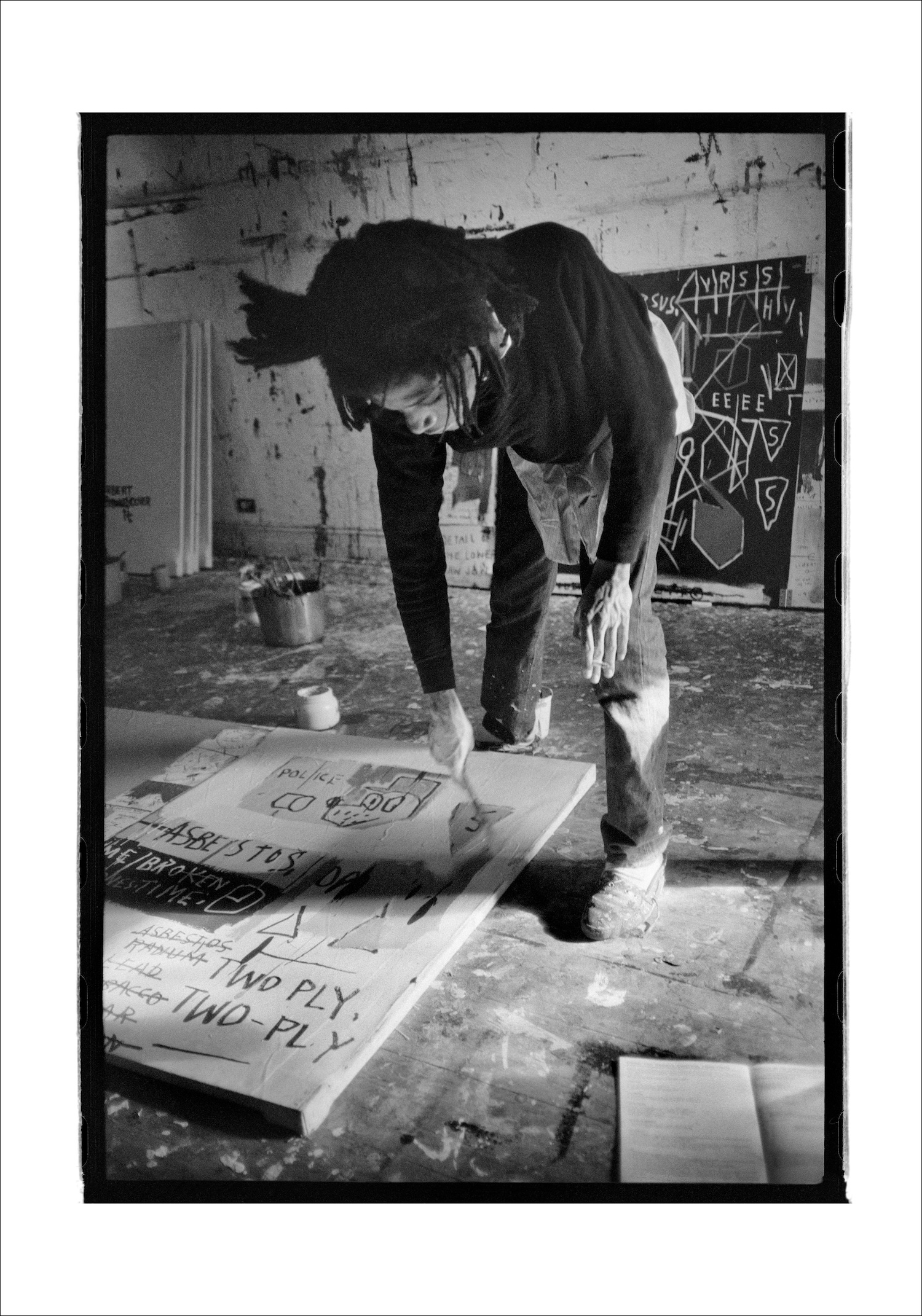

The show packages Basquiat’s work into neat periods: this is him when he was fresh and untamed; this is him when he was adopted by the art world’s elite whose patronage he sought- on Friday, August 12, 1988 he died alone in the apartment he rented from Mr. Warhol’s estate; this is him being not just an energetic painter but a rock star, an activist, a TV star; this is him epitomising an era. It’s almost as if everything he ever did is on display and worthy of study. You get photos of his ‘SAMO’ graffiti -SAMO stood for “Same Old Shit” – “SAMO© SAVES IDIOTS AND GONZOIDS…”, “SAMO©… 4 THE SO-CALLED AVANT-GARDE” and “SAMO as an alternative 2 playing art with the ‘radical chic’ sect on Daddy’s$funds” – and pages from a diary presented as artefacts, each framed and ready to decorate a clean wall at your corporate HQ.

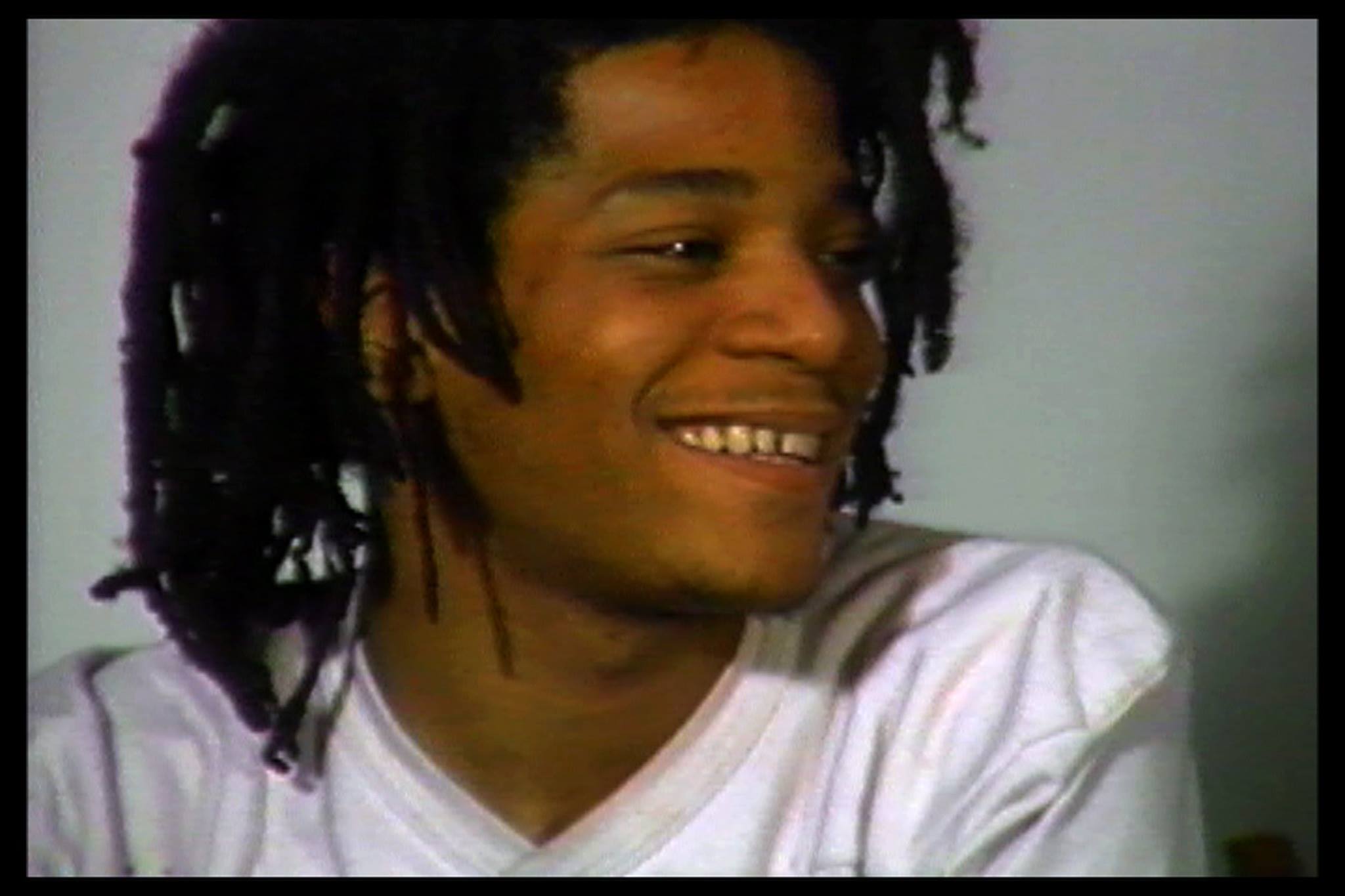

You leave the big show – 14 rooms of retro videos, multi-sensory artefacts and vibrant paintings – dazzled but unsatisfied. Which brings us to Paul Tschinkel’s film, which features an insightful meeting between Basquat and scholar Marc H. Miller. Miller tells me: “It occurred to me that with the Basquiat show opening at the Barbican that you might also have interest in the videotape interview that I did with Jean-Michel back in 1982 just when his career was taking off.”

He’s right. I am. The interview is excellent, allowing Basquiat time to talk. We see beyond the celebrity. I spoke with Miller.

Could you tell me more about ART/new york – when it began and why you started it it was started?

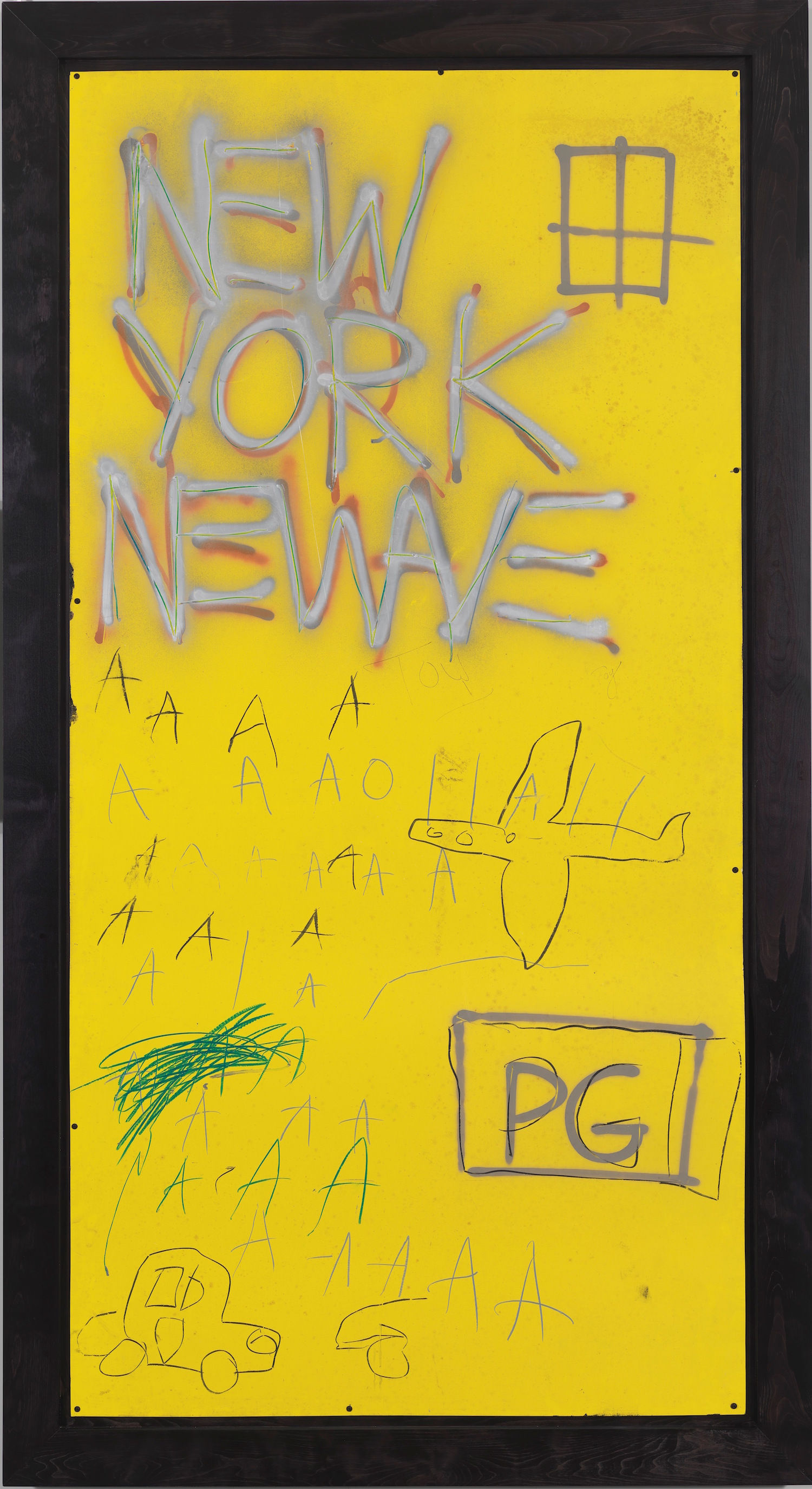

Paul Tschinkel started ART/new york. He had bought a portable video camera (then new on the market), and had the idea to tape art exhibitions with artist interviews and to market the programs to schools, museums, and libraries. I joined up with Paul in 1981 as the art historian doing the interviews and writing the commentary. The first show we taped was “New York/New Wave” at the art space P.S. 1, the first exhibition to feature Basquiat. Paul and I were both impressed by his work, and featured it conspicuously in the “New York/New Wave” program. A year later, Paul and I became interested in what was being called “neo-expressionism.” Our tape “Young Expressionists” covered rising stars Julian Schnabel and Francesco Clemente. Of the many young expressionists we could have chosen for the third slot, we selected Basquiat, who was much less known, but clearly a major talent.

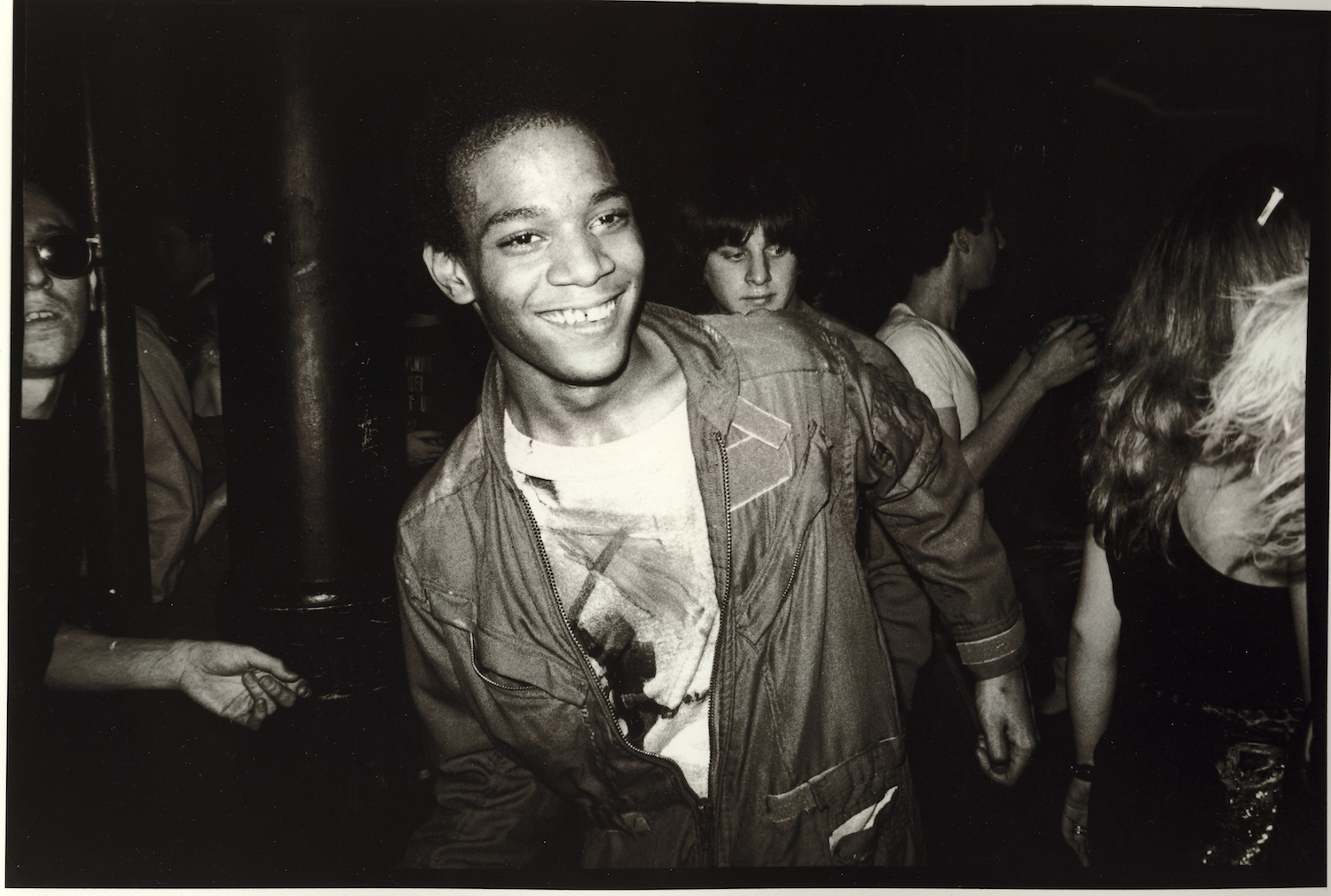

Jean-Michel’s experience with video had been mostly with Glenn O’Brien’s free-for-all cable show, “TV Party.” By contrast, the ART/new york tapes had a very specific educational purpose and audience. Basquiat had seen the “New York/New Wave” tape and knew exactly what we were aiming for. He seemed to relish the intellectual sparring, and even dressed for the occasion, wearing a t-shirt from Wesleyan, an elite private university with art-world cachet (which he hadn’t attended). While most people at the time assumed he had little background in art and worked intuitively, the interview revealed a deliberative artist with broad knowledge and a unique creative slant.

Do you think Basquiat was more exploiter than exploited? His SAMO graffiti was about getting noticed by the art world. I read that he spotted Warhol eating lunch and sold him a handmade postcard. He was wooing his sugar daddy?

Basquiat was like any other young artist trying first to attract attention, and then to function in a capitalist system dominated by a few powerful dealers. During the interview, I asked him if his race was more an advantage or a disadvantage. He replied, “I don’t exploit it.” When asked if others exploit it, he answers, “It’s possible.” He and Al Diaz put up the SAMO graffiti near art galleries and the hip clubs because that was where they, like other young artists, hung out. Just about every young artist wanted to get Warhol’s attention. He was a starmaker, and forged a relationship with Basquiat because he saw his talent.

Was he exploited?

Probably no more than any other successful artist whose work is in demand. Just as we were packing up after the interview, the renowned art dealer Bruno Bischofsberger arrived at Basquiat’s studio with an entourage of about five people. They went through the place as if they owned it, putting together a pile of works to take. I wish we had caught this on camera. Basquiat stood there with his arms crossed. I seriously doubt that an inventory was kept, although I don’t know this for sure. The bottom line, though, is that Basquiat became very rich very quickly while he was still in his early 20s. That’s not common in the art world.

And what of his legacy – is it vulgar that his art is now just another thing to own?

For someone who lived such a short life, Basquiat produced a remarkable amount of work. It is a rich legacy, a unique creative expression of life at the end of the 20th century. His energetic paintings express our chaotic, plugged-in world, where people are bombarded with stimuli from every direction. Basquiat portrays his own moods, feelings, and interests. As he explains in the interview, he pulls from what is around him: “real life, books, television.”

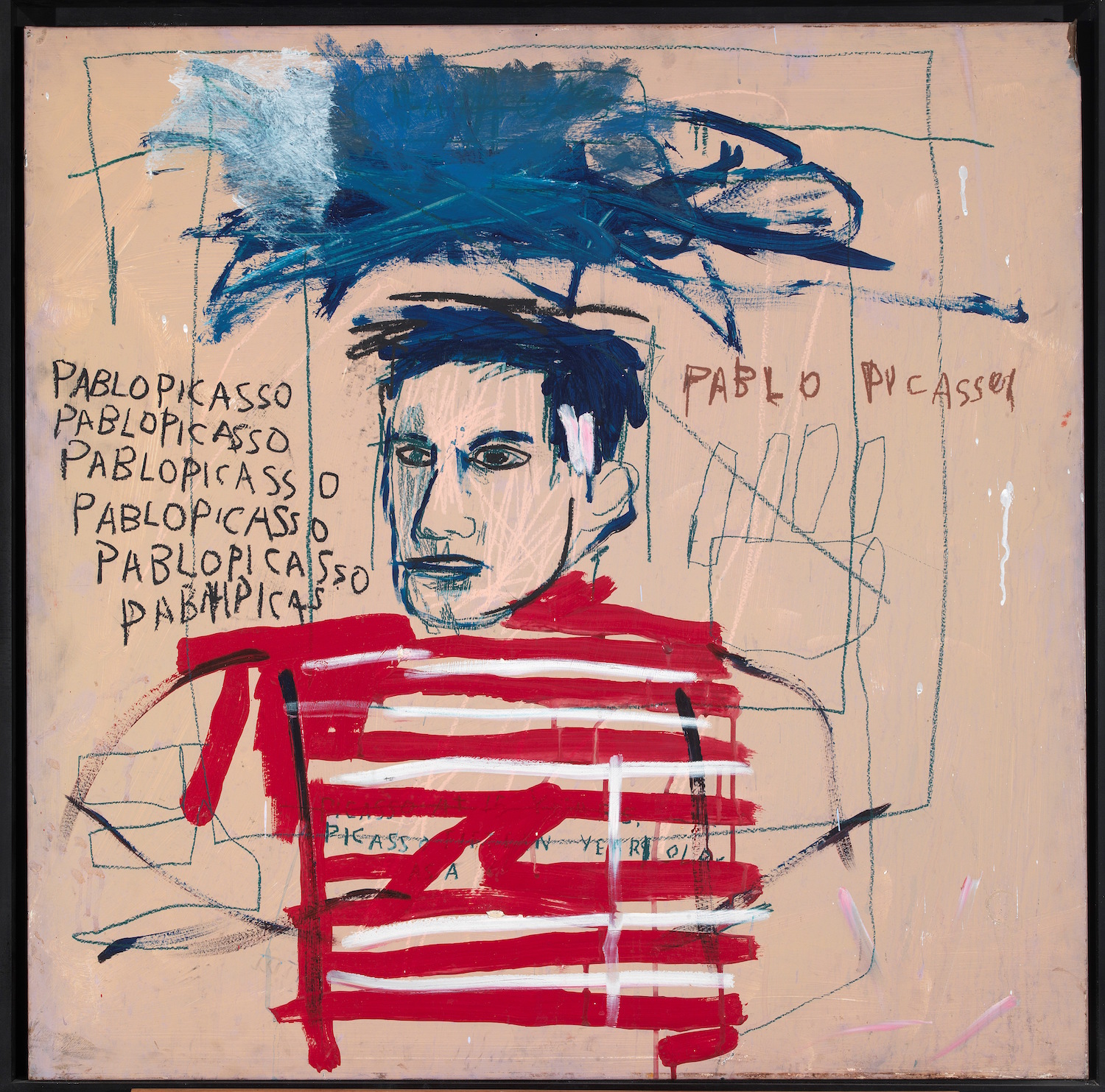

Basquiat’s art should not be pigeonholed by race, but its importance in that regard cannot be ignored. Before Basquiat, you could count on one hand the number of successful black artists in America and Europe. He opened the way for many, many more. By incorporating references to black history, black heroes, and Afro-Caribbean culture, he helped expand the range and content of Western Art. Basquiat can also be credited with helping to change the critical language used to discuss works by black artists. I discovered this firsthand when I quoted a critic who called his work “primal expressionism.” Basquiat’s quick retort, “Like an ape? A primate?”

And success?

If Basquiat were alive today he would have no problems with his current success. He knew he was great artist, but more importantly he never compromised or pandered. The fact that his paintings are now worth millions of dollars does not detract from their greatness. In fact, it allows more people to appreciate them. Look at the publicity around the Barbican exhibition, where the value of the paintings is often the hook. Not everybody will see past the price tag, but many will.

“THESE INSTITUTIONS HAS THE MOST POLITICAL INFLUENCE A.TELEVISION B. THE CHURCH C. SAMO D. MC DONALDS’, Downtown 81, Edo Bertoglio ©New York Beat Film

Marc shares more about the meeting:

“In the early 1980s Basquiat was a regular in the downtown art and club scene, where he often crossed paths with Paul Tschinkel and me. Our friend Patti Astor, the co-director of the Fun Gallery, wanted us to tape the exhibition and encouraged Jean-Michel to do the interview.

“Basquiat was just waking up at 3 pm when we arrived at his second floor loft on 101 Crosby Street just east of Soho. Basquiat was a child of the television age and seemed eager to perfect his video persona. In the interview Basquiat emerges as a man of few words and short replies, and I quickly ran out of prepared questions. He was most comfortable talking about his paintings. He was less comfortable talking about the specifics of his life and the way he was being portrayed in the press. For the most part, Basquiat appeared to be having fun, revealing a light, playful side when talking about his art, and a more cutting wit when confronted with misconceptions and hints of racial stereotyping. At some moments he tightened up, perhaps wary of revealing too much, or alert to the danger of puncturing the mystery of his art. The videotaping moved quickly with Basquiat fully engaged right up to the humorous food-munching scene that was his way of bringing the 40-minute interview to a close.”

LIKE AN IGNORANT EASTER SUIT, Jean-Michel Basquiat on the set of Downtown 81, Edo Bertoglio ©New York Beat Film LLC

So we get to see Basquiat. But the business of art needs its subject buffered, heroic and bracketed. Marc writes:

“The restaging of the interview in Julian Schnabel’s film Basquiat (1996), with bad guy actor Christopher Walken playing my part, however, is another thing entirely. At some point in 1995 as I was walking along West Broadway in Soho, Schnabel bolted across the street shouting at me, ‘That’s no way to conduct an interview!’ Perhaps he was at that very moment conceiving his own version of the interview in which Basquiat would be portrayed as a vulnerable outsider in a hostile and cynical art world. Schnabel had access to the complete unedited interview and honed in on the sections where Basquiat was most reticent. In his restaging, Walken (the Interviewer) and Jeffrey Wright (Basquiat) use words, phrases and body language from the interview but, by means of artful selectivity and outright fabrication, the friendly mood of the actual conversation is transformed into something aggressive and vaguely sinister. Most troubling are the totally made-up parts where Walken calls Basquiat a ‘pickaninny’, and confronts him with ‘having a mother in a mental institution’. This may be dramatic filmmaking but it is a distortion of the truth.”

VIDEO: ART/new york, Jean-Michel Basquiat at the Fun Gallery, an excerpt from the video program “Young Expressionists,” 1982. By permission of Paul Tschinkel. A DVD of the full, unedited 40 minute interview with Basquiat can be obtained from the ART/new york website. http://artnewyork.org

And now for the art…

Rammellzee vs. K-Rob, produced and with cover artwork by Jean-Michel Basquiat, beat Bop record, 1983, Courtesy Jennifer Von Holstein

Jean-Michel Basquiat and Jennifer Stein, Anti Baseball Card Product, 1979, Courtesy Jennifer Von Holstein

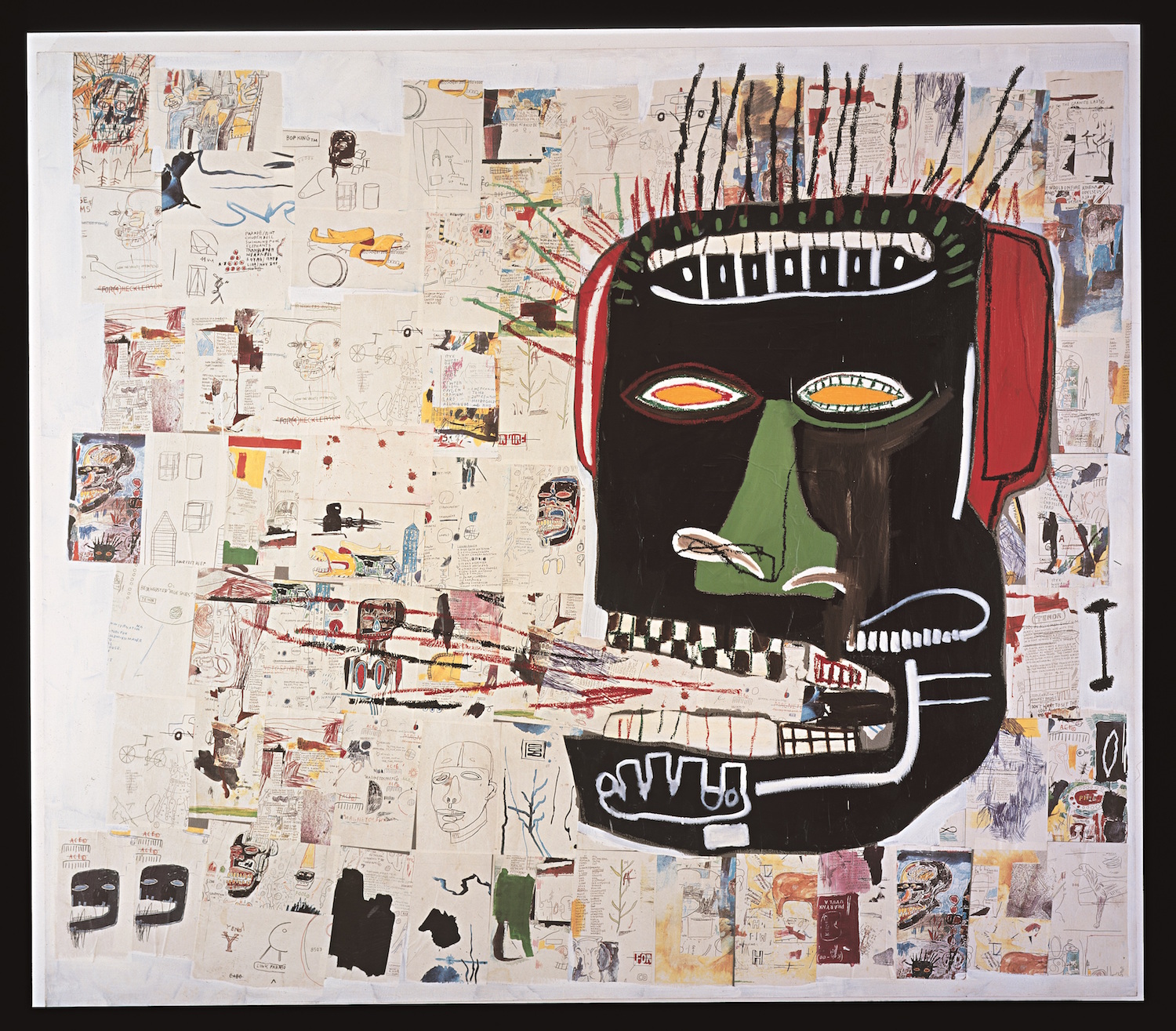

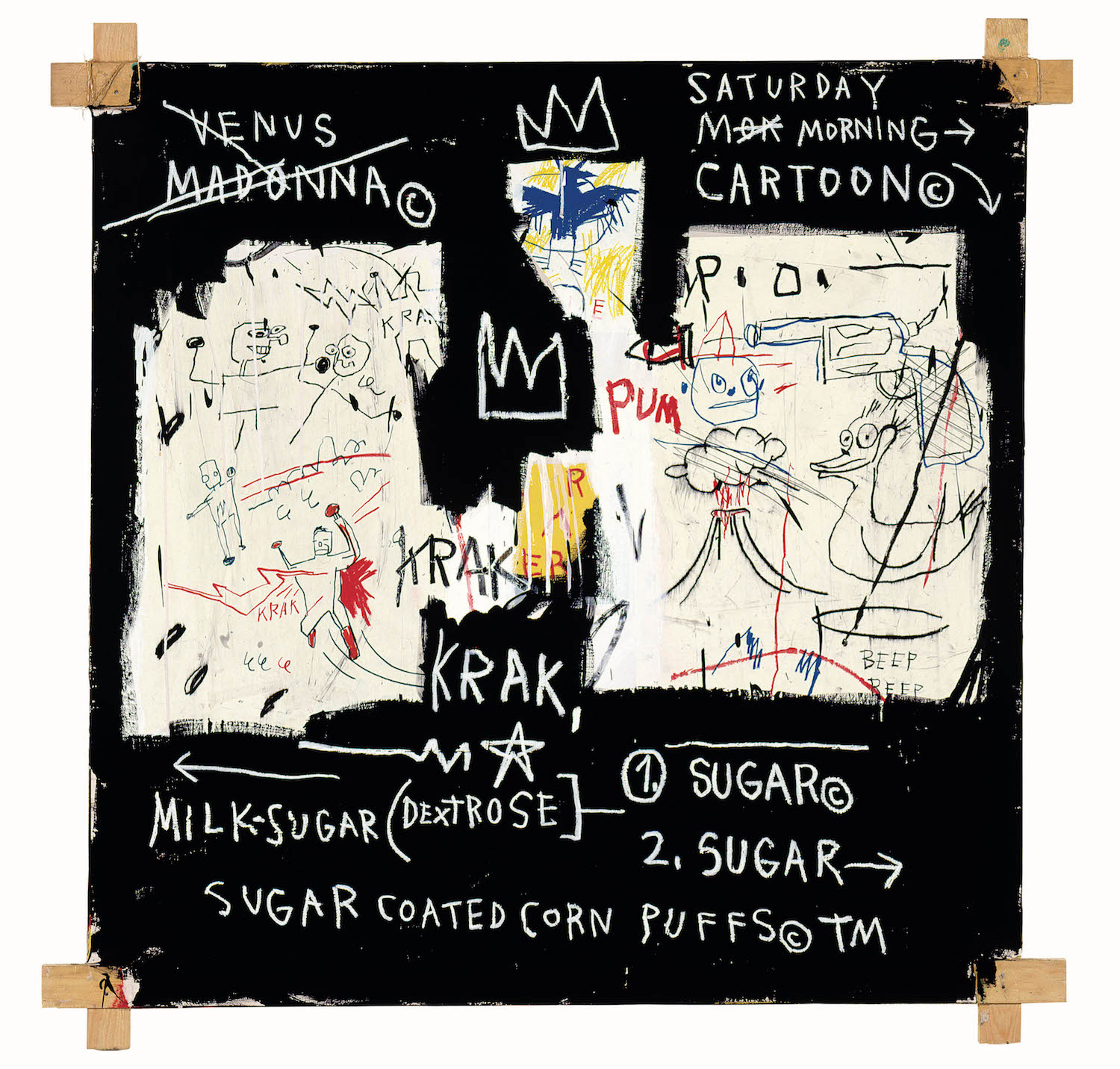

Jean-Michel Basquiat

Untitled, 1980

Courtesy Whitney Museum of American Art, New York.

© The Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat/ Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/ ADAGP, Paris. Licensed by Artestar, New York.

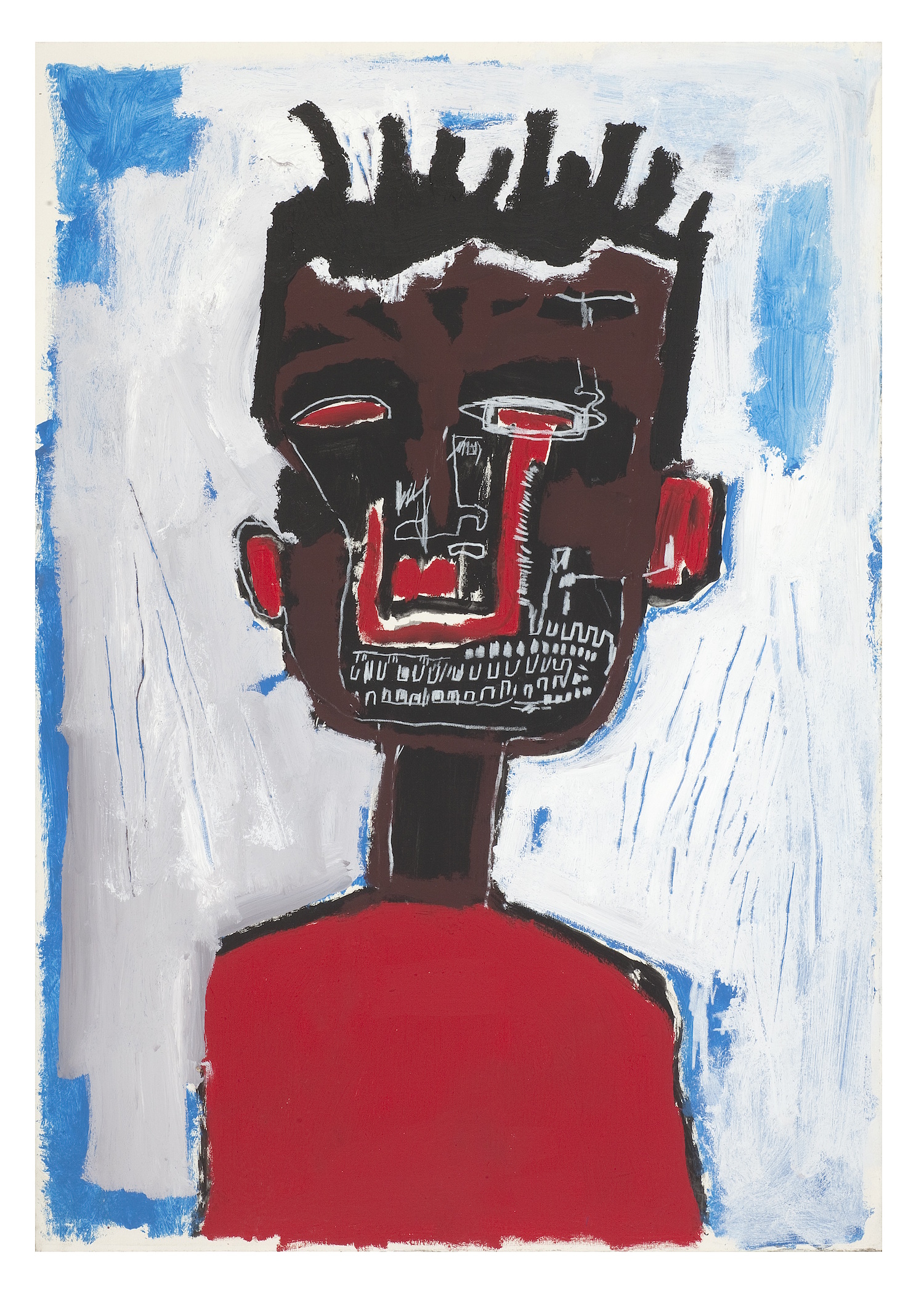

Jean-Michel Basquiat

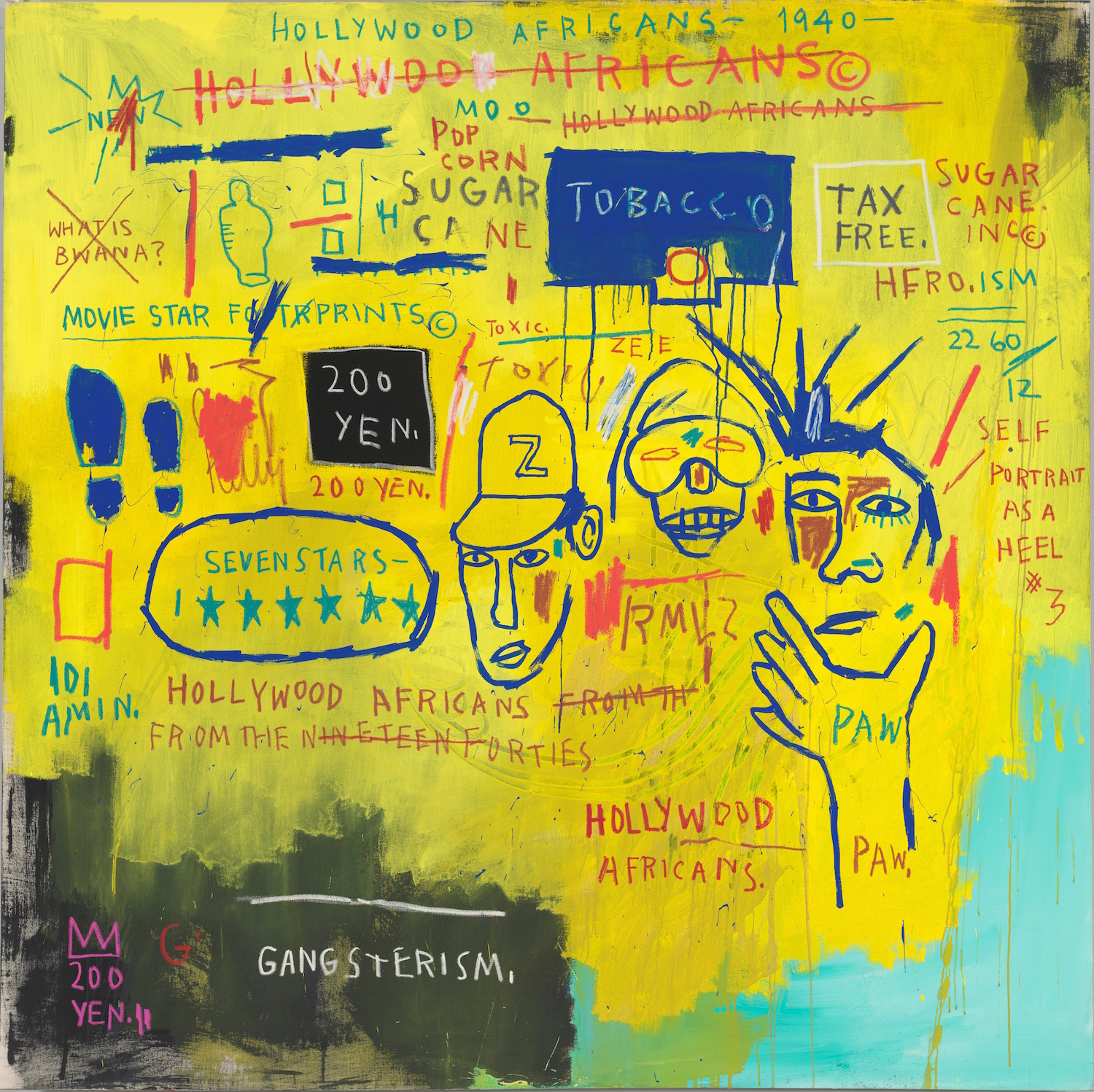

Hollywood Africans, 1983

Courtesy Whitney Museum of American Art, New York.

© The Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat/ Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/ ADAGP, Paris. Licensed by Artestar, New York.

© The Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat/ Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/ ADAGP, Paris. Licensed by Artestar, New York.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.