Butlins Barry Island The-Main Arcade Edmund Nagele

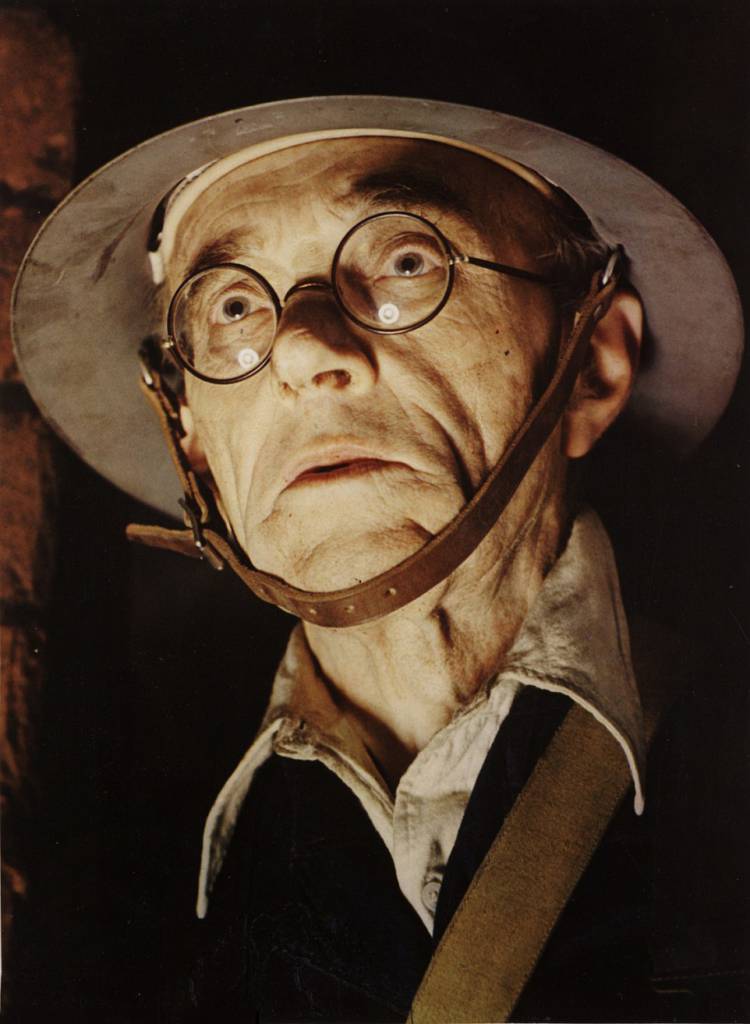

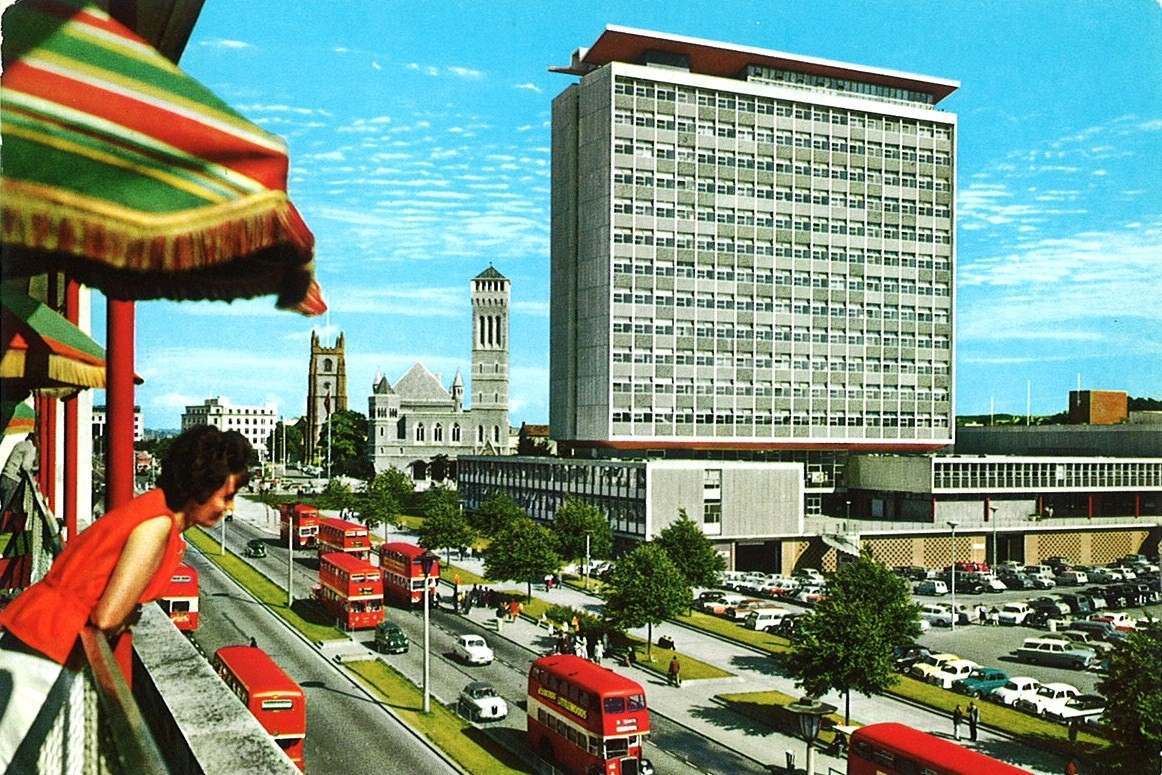

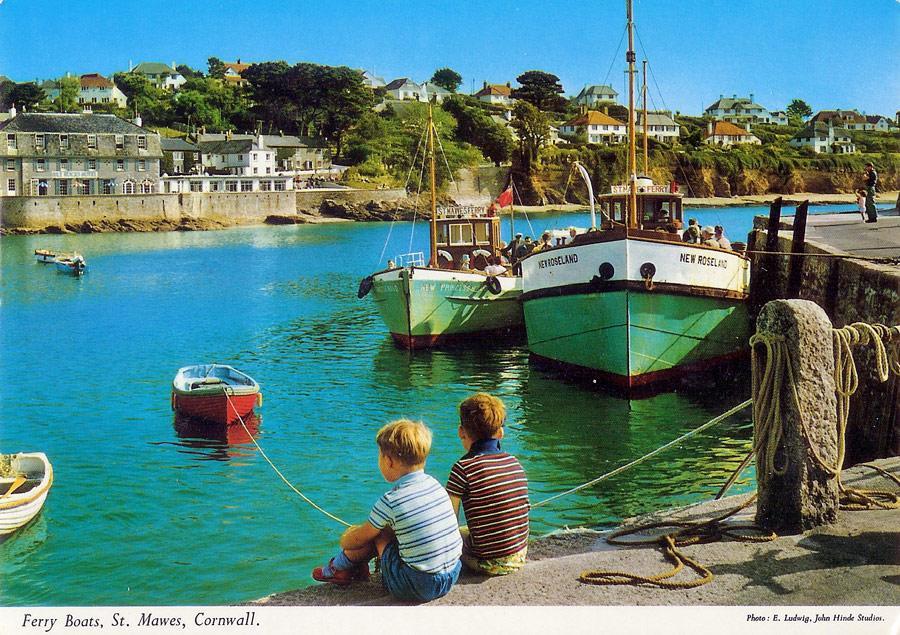

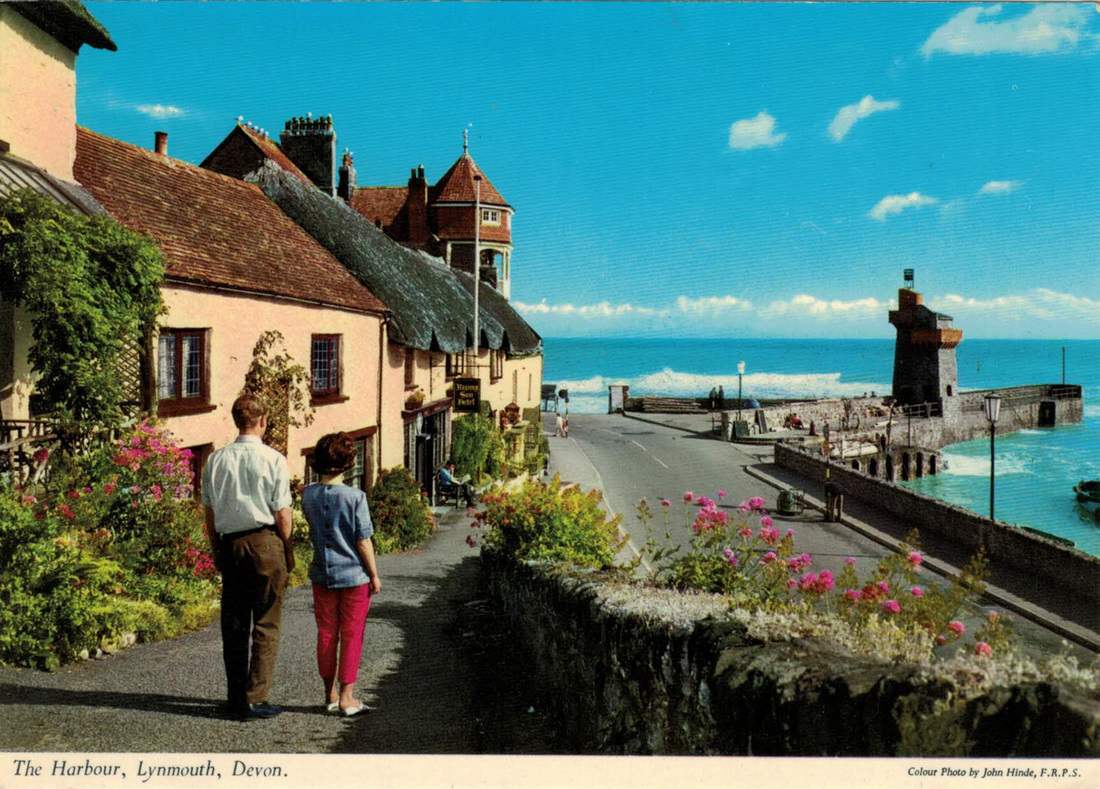

The photographer Martin Parr once described the postcards of John Hinde as “some of the strongest images of Britain in the 1960s and 1970s”. Parr noted that Hinde was: “fastidious about the colour, the saturation, the technique, and that paid off.” John Wilfrid Hinde who had been born in Somerset in 1916 trained at the Reimann School of Photography and then setup a studio in London working as a documentary, war and advertising photographer. He produced some stunning pictures during WW2 including a notable close-up of a Fire Warden in 1944, the year after he had been made a Fellow of the Royal Photographic Society.

After the war John Hinde got a job managing and publicising several circuses in Ireland and then decided to set up his own called the John Hinde Show along with his wife-to-be Antoina Falnoga, a trapeze artist. Unfortunately it was one of Ireland’s rainiest years, which is of course saying something, and it failed spectacularly. Needing money desperately he set up a postcard company featuring his photographs. Shannon Airport had recently opened which brought thousands of Irish-American tourists all anxious for momentos to take back to America. Sean O’Hagan wrote in an article in the Guardian:

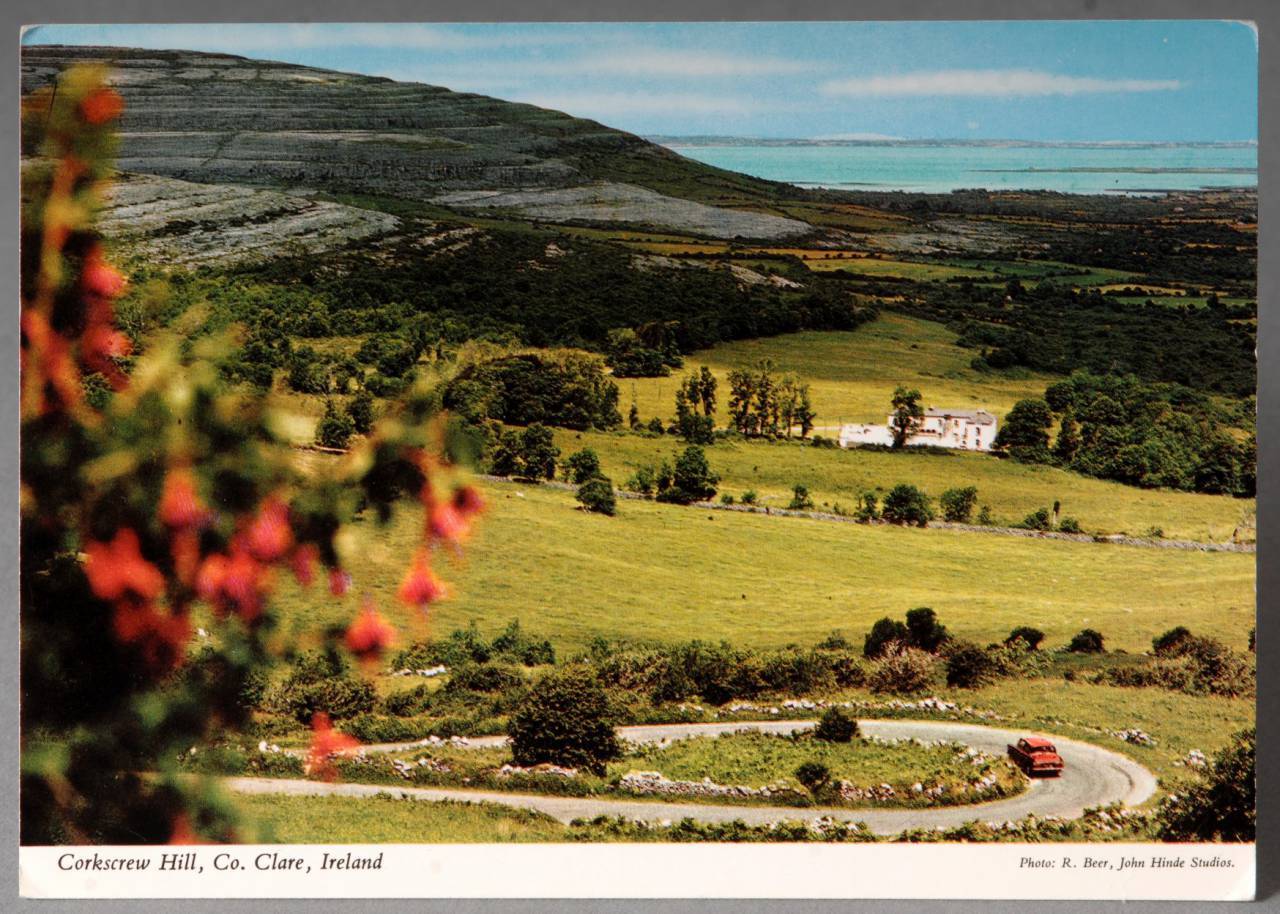

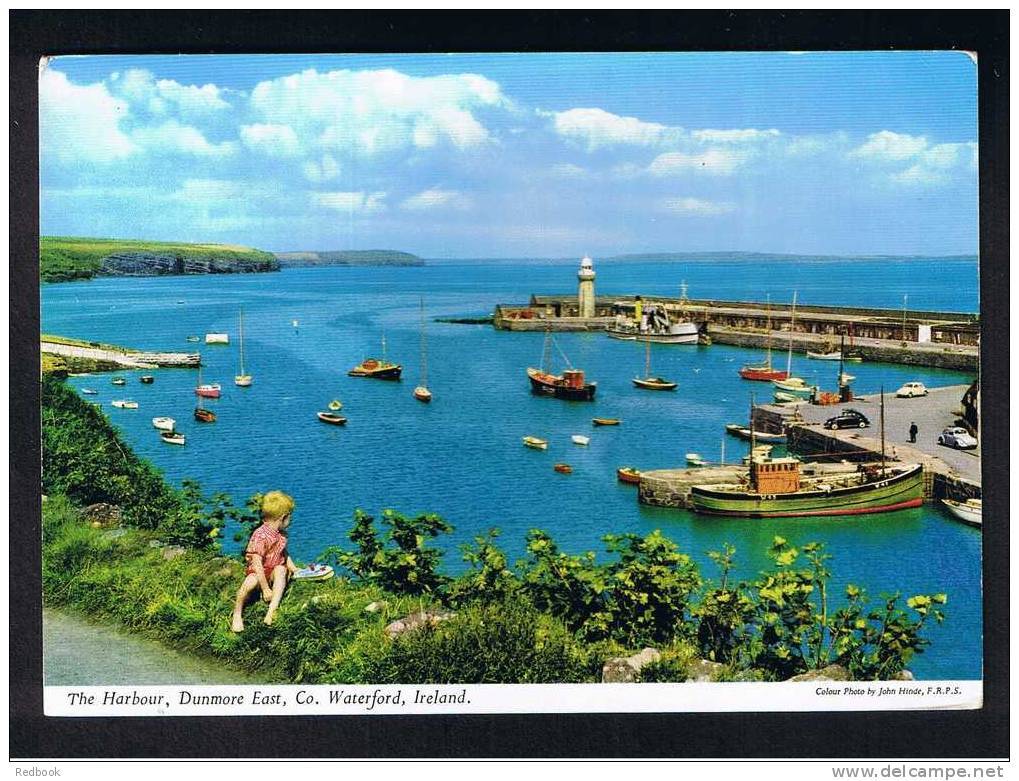

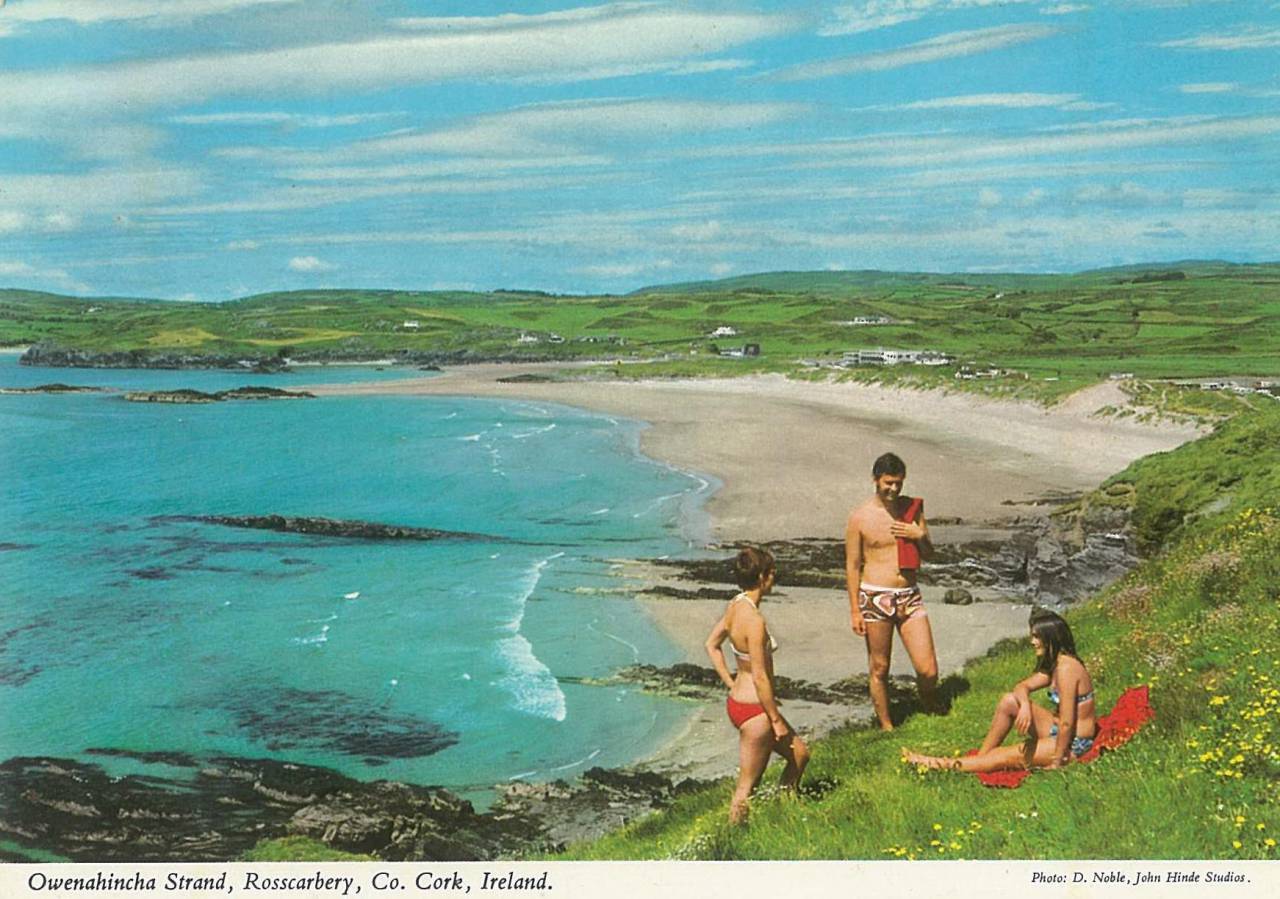

Hinde, perhaps unsurprisingly, was an Englishman, and thus unafraid to exaggerate what many Irish photographers choose to underplay – the otherworldliness of the landscape and the tweeness of stereotypical Irish images (donkeys, colleens, etc).

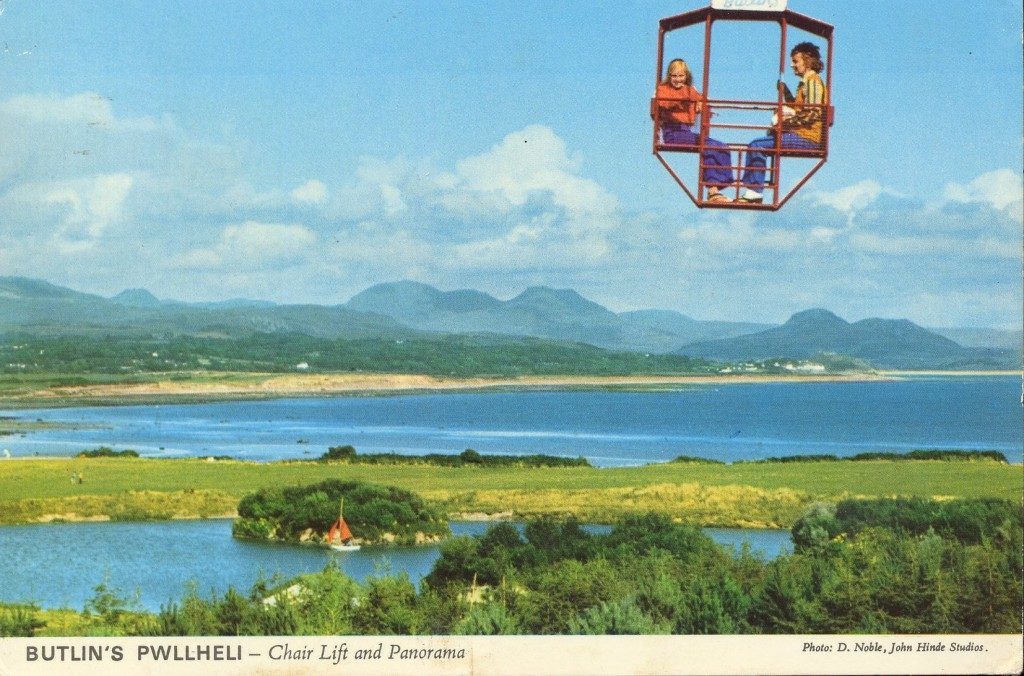

John Hinde once told an interviewer that his colour photographs were an attempt ‘to visualise heaven’, but he also spoke about his postcards with slightly more understatement, “In some cases the lily is gilded . . . slightly.” Hinde and his photographers (by 1965 he had employed two young German photographers, Elmar Ludwig and Edmund Nägele, as well an Englishman, David Noble, to carry on his work) would routinely stick flowers in the foreground to add colour; “a little gardening”, it was called. By 1966 John Hinde was running one of the largest postcard companies in the world. Kate Burt in the Independent wrote about what was different about Hinde’s postcards – which was essentially his use of colour:

Hinde was an innovator in a world where serious photography was black and white, and where colour photography was poor – because neither Ireland nor Britain had the technological capabilities to reproduce the vibrant hues Hinde dreamed of. So he sent his transparencies to Italy, where technology was more advanced. Not only could the images be produced in far lusher shades than was possible over here, they also got additional help with extensive retouching, which would turn insipid sweaters, mousey heads of hair, faded sun-loungers and dull skies into dazzling points of interest. (And, more importantly, according to those who knew him, into hard cash.)

Sean O’Hagan again described how the John Hinde photographers went about their work:

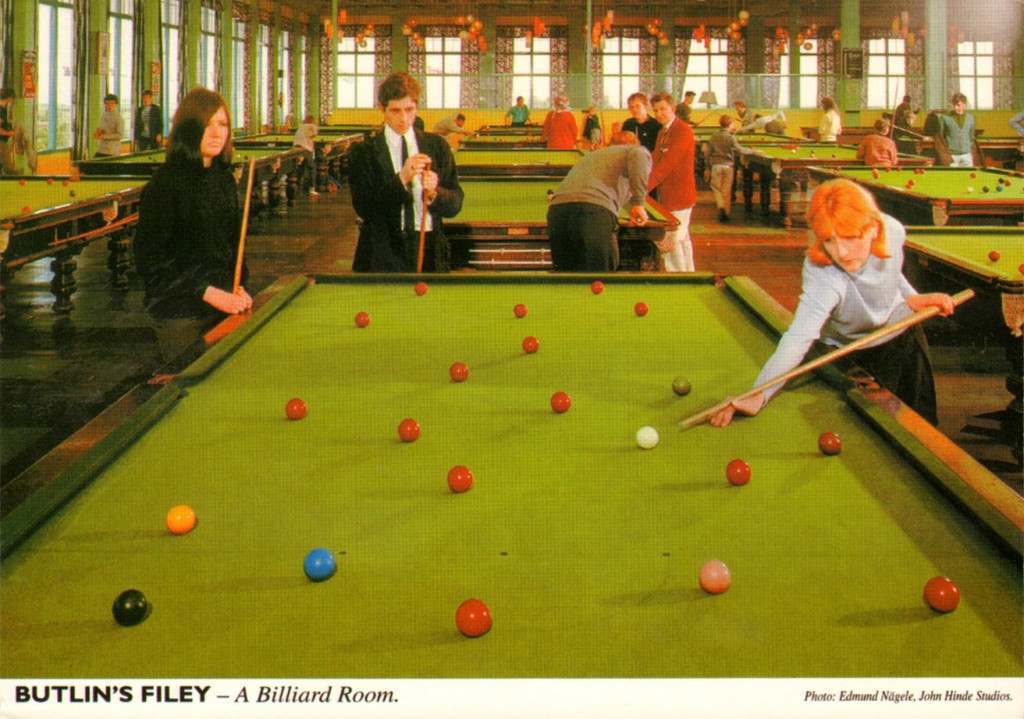

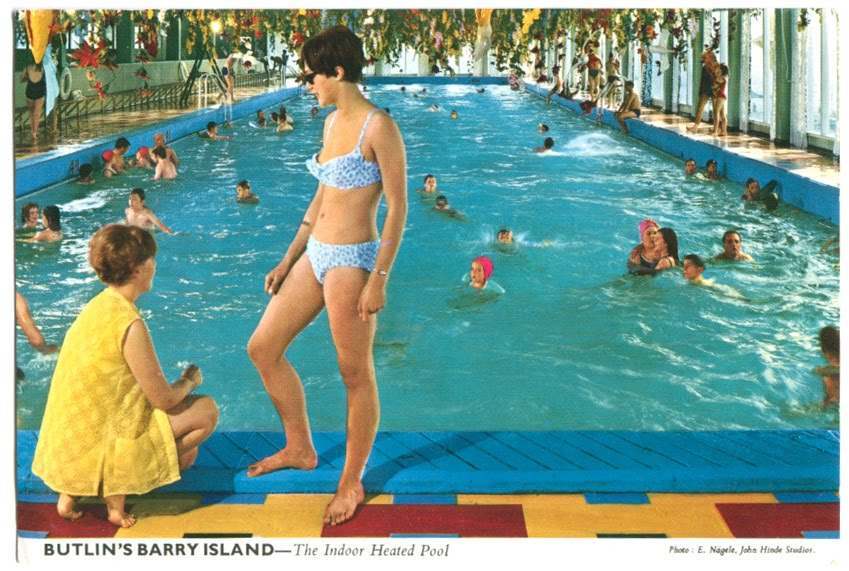

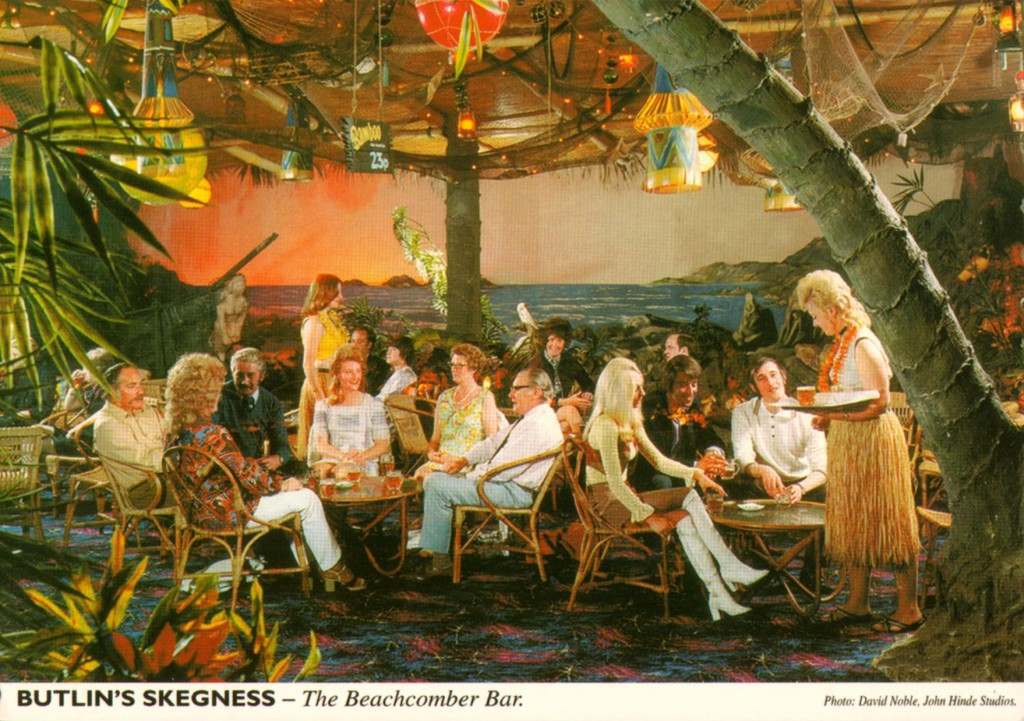

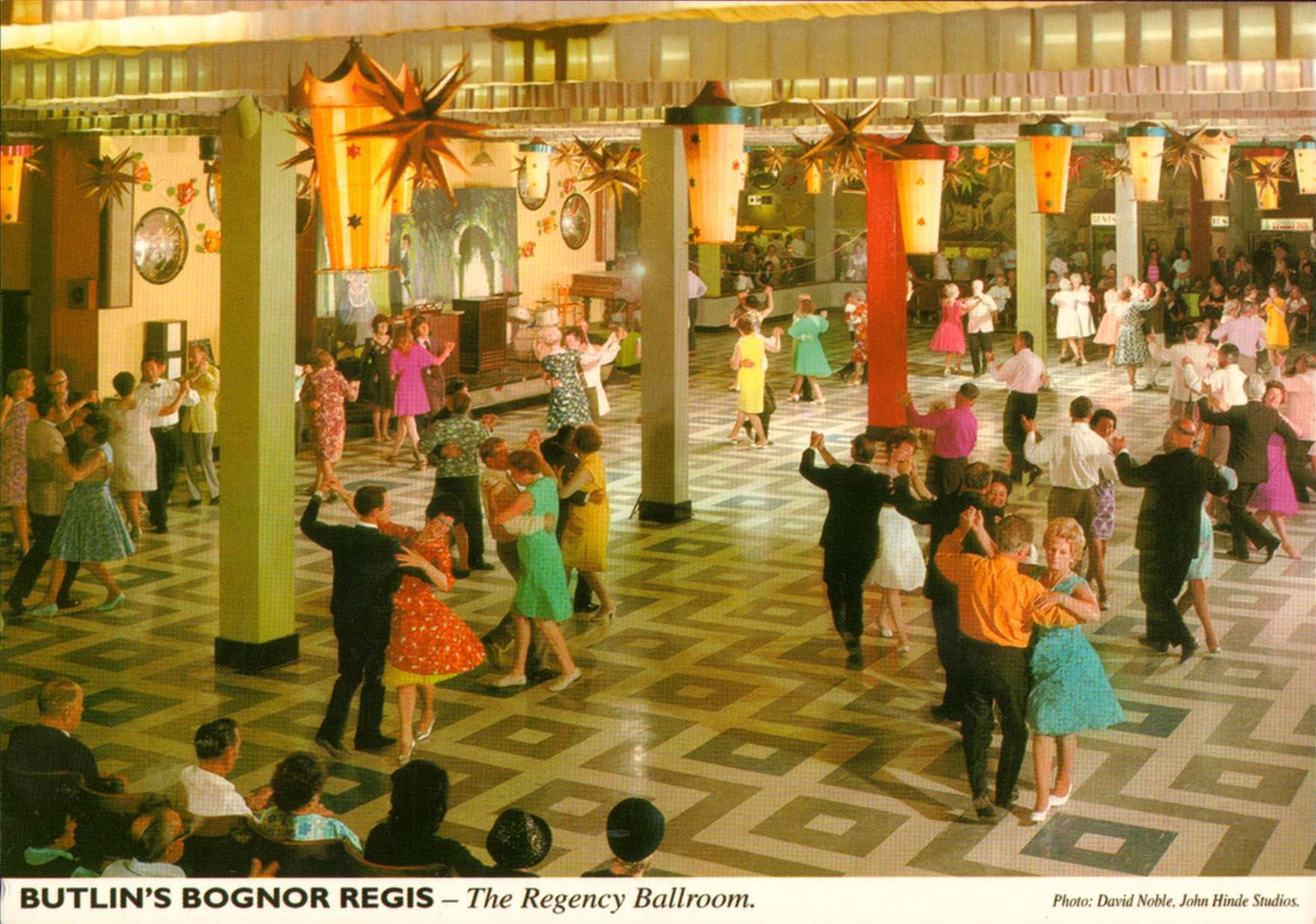

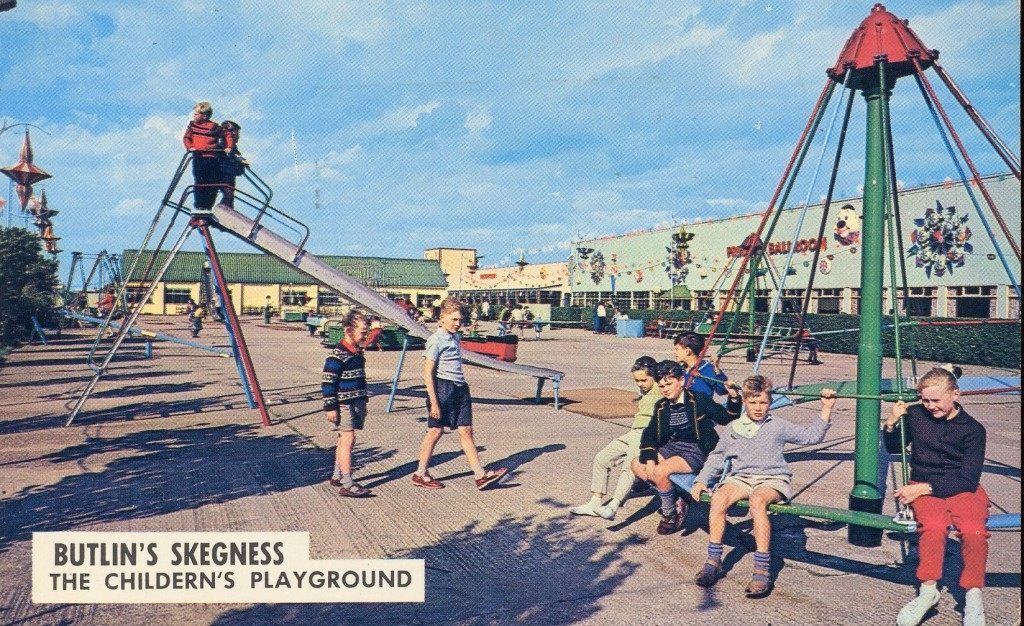

Their task was a complex one that included the setting up of the tableaux, the arranging of often large numbers of holidaymakers who would act out elements of their Butlin’s experience in lounge bars, sun loungers and dance halls. Preparation and pre-lighting often took a day, and an image was captured in one shot before the impatient punters grew restless. From his studio in Dublin, Hinde oversaw the colour-separation process that, above all else, invests his work with such an unreal sheen.

Edmund Nagele was 21 when he joined the company. For him and the other photographers, May to September was spent “living like gypsies”, driving around Britain and Ireland in Hinde’s LandRover/caravan combo, which still bore the ‘John Hinde Show’ signage from the circus days. “It could be a bit embarrassing,” recalled Nagele. Kate Burt described how Nagale went about photographing scenes at Butlin’s:

“It was hard,” he says. “You couldn’t do it nowadays – but in the 1960s and 1970s people had a different mentality. We’d get a Redcoat to help us. They’d announce: ‘We have a photographer today. Please stand still for four seconds when he asks’. It was never, ‘Would you mind…?’. The first time you do it, with a room of 200 people, you’re scared shitless.”

No wonder: it took a whole day just to rig up the (one-use only) flash reflectors. Ninety or so would be tucked behind pots of plastic flowers in the bar or ballroom. And then, with everything in place, and “pretty girls in the foreground”, there was just one chance to get the shot. “It was a nailbiting moment,” Nagele says. He remembers only one disaster, which resulted in an emergency trip to London to replace all the flashbulbs in order to reshoot.

Hinde’s postcards were immensely popular, despite Hinde’s view that his photographs held no artistic value. In 1972, he decided to sell his company to the Waterford Glass Group to pursue his love of landscape painting.

Even though Hinde never viewed his photographs with much reverence, the Irish Museum of Modern Art recognised his photographic works with a retrospective in Dublin in 1993. Since his death in 1998, exhibits of his photography have travelled all over the world and he proved to be the most successful postcard producer in the world. His works have also been compiled into books, including the much sought after Hindesight, a collection of the Ireland postcards and Our True Intent Is All For Your Delight, a collection of the Butlin’s postcards.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.