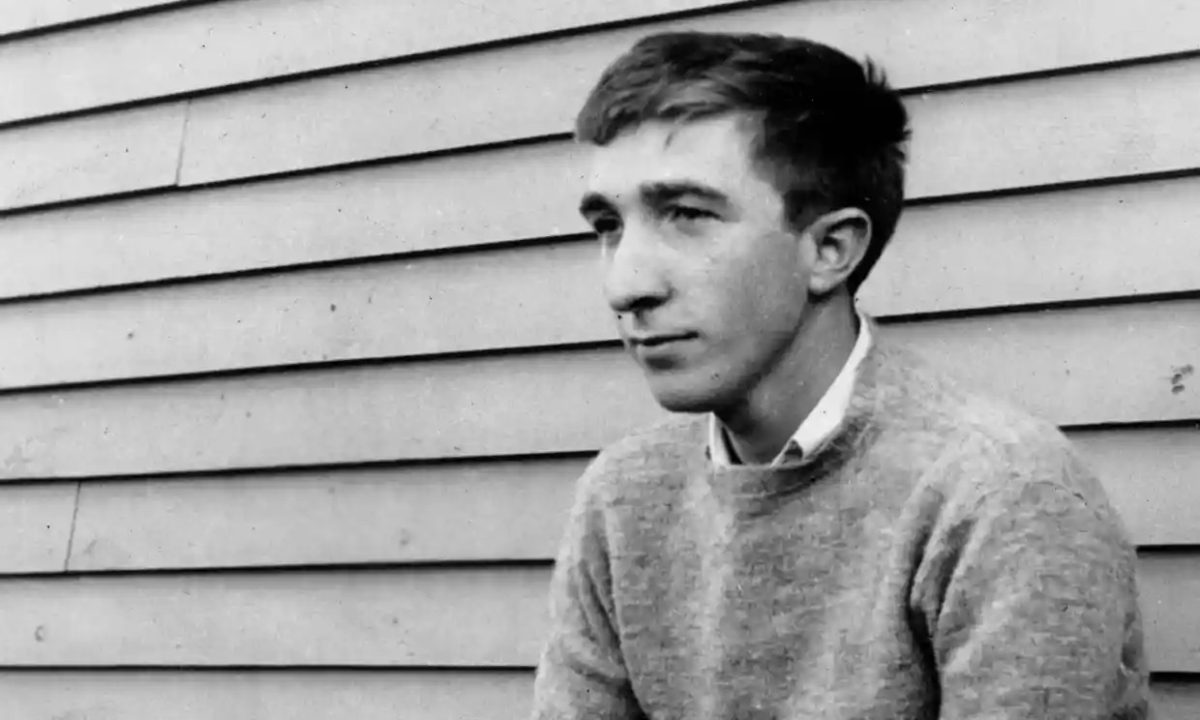

John Updike’s (March 18, 1932–January 27, 2009) memoirs consist of six discontinuous chapters in lieu of an autobiography, written soon after someone informed him of a “repulsive” plan to write his biography, “to take my life, my lode of ore, my heap of memories from me.”

Others would surely explore the writer’s consciousness, but he’d commune with the past and get their first.

In the book’s foreword he says that he tried to “to treat this life, this massive datum which happens to be mine, as a specimen life, representative in its odd uniqueness of all the oddly unique lives in this world.”

But, “These memoirs feel shabby,” the writer best known for his Rabbit tetralogy writes in Self -Consciousness (1996). “Memory is like the wishing-skin in fairy tales, with its limited number of wishes. His, he writes, has been “used up and wished away in the self-serving corruption of fiction.”

Can writing preserve memories and keep death at bay? Who gets to tell Updike’s story after he’s gone, and how will he be remembered? “Age I must, but die I would rather not,” he wrote in Endpoint and Other Poems. “Be with me, words, a little longer.”

Landscape of the Vernal Equinox (III) Paul Nash – 1944. Prints.

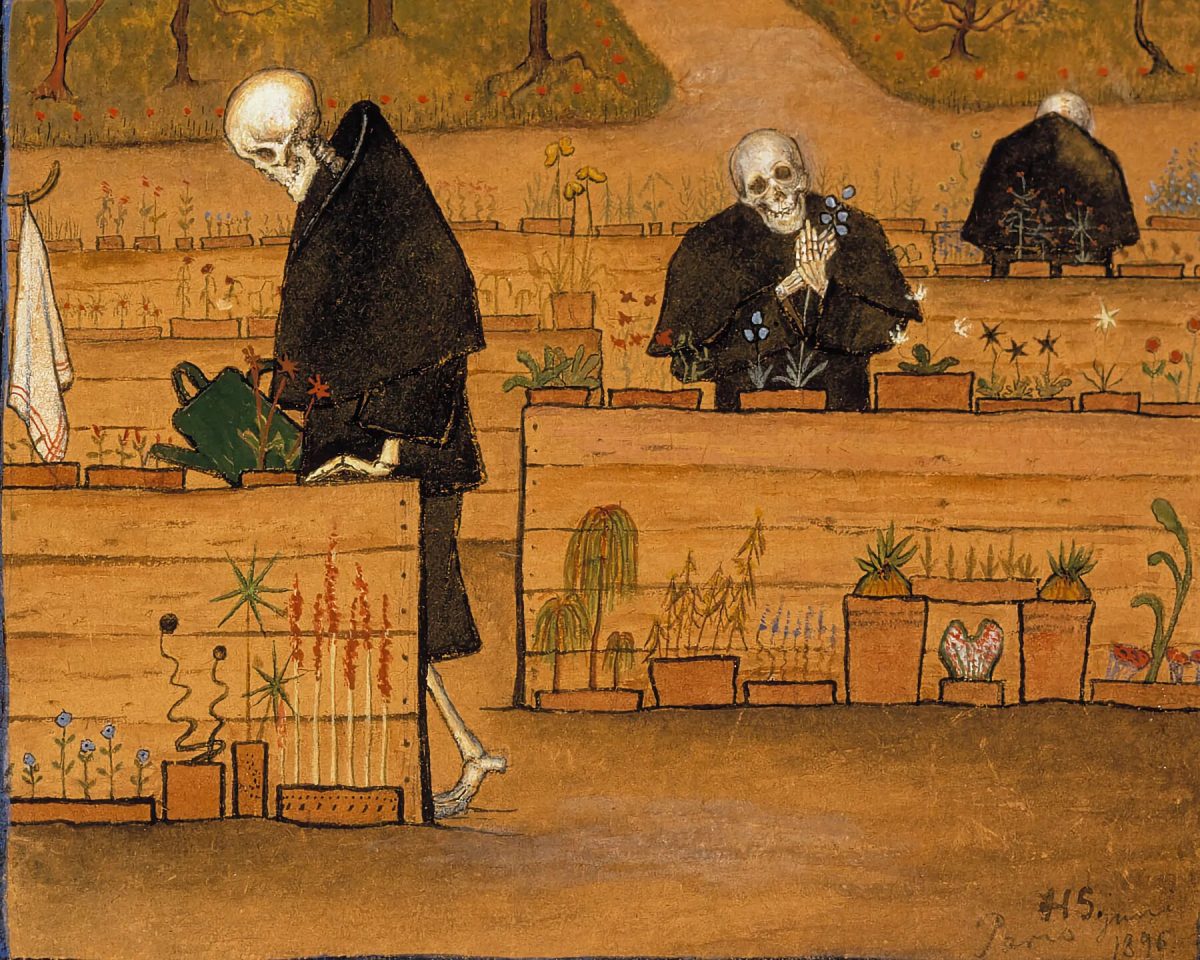

The book’s final part (‘On Being a Self Forever’) deals with death, a theme the prolific writer touched on in The Afterlife and Other Stories, in which “in the winter of their lives” it dawns on his ageing characters that “nobody belongs to us, except in memory”. It’s a distancing touched up by Updike’s mother, from whom he inherited a love of writing and psoriasis. When asked about her son’s fame in later years, she replied: “I’d rather it had been me.”

Can writing preserve memory, however subjective, even holding death at bay? For Updike writing was “an addiction, an illusory release, a presumptuous taming of reality, a way of expressing lightly the unbearable.

“That we age and leave behind this litter of dead, unrecoverable selves is both unbearable and the commonest thing in the world — it happens to everybody. In the morning light one can write breezily, without the slight acceleration of one’s pulse, about what one cannot contemplate in the dark without turning in panic to God. In the dark one truly feels that immense sliding, that turning of the vast earth into darkness and eternal cold, taking with it all the furniture and scenery, and the bright distractions and warm touches, of our lives. Even the barest earthly facts are unbearably heavy, weighted as they are with our personal death. Writing, in making the world light — in codifying, distorting, prettifying, verbalizing it — approaches blasphemy.”

The Garden of Death by Hugo Simberg – 1896. Prints.

Before more of his thoughts on death, we see Updike’s childhood (‘A Soft Spring Night in Shillington’) as he walks around his hometown streets on a misty night in 1980 – a place he loved “as one loves one’s own body and consciousness, because they are synonymous with being.”

This was America’s middle he wrote of. “My subject,” Updike told Life reporter Jane T Howard in 1966, “is the American Protestant small-town middle class. I like middles. It is in middles that extremes clash, where ambiguity restlessly rules. Something quite intricate and fierce occurs in homes, and it seems to me without doubt worthwhile to examine what it is.”

We experience his battles with asthma and psoriasis (‘At War with My Skin’), something he spoke of in From the Journal of a Leper – “I cannot pass a reflecting surface on the street without glancing in, in hopes that I have somehow changed”; his stammer (‘Getting the Words Out’) and how a love of writing gave redemption; his ambivalence to the Vietnam War (‘On Not Being a Dove’); and the “big, bumptious race” of Updikes (‘A Letter to My Grandson).

But it’s in talking of death that strikes. Updike wonders “Where does the self dawn?”, asserting that “the self’s responsibility… is to achieve rapport if not rapture with the giant, cosmic other: to appreciate, let’s say, the walk back from the mailbox.”

Not only are selves conditional but they die. Each day, we wake slightly altered, and the person we were yesterday is dead. So why, one could say, be afraid of death, when death comes all the time? It is even possible to dislike our old selves, those disposable ancestors of ours. For instance, my high-school self — skinny, scabby, giggly, gabby, frantic to be noticed, tormented enough to be a tormentor, relentlessly pushing his cartoons and posters and noisy jokes and pseudo-sophisticated poems upon the helpless high school — strikes me now as considerably obnoxious, though I owe him a lot: without his frantic ambition and insecurity I would not be sitting on (as my present home was named by others) Haven Hill.

Updike saved almost everything. His papers, stored at Harvard, include his golf scorecards, legal and business records, fan mail, video tapes, photographs, drawings and rejection letters. Was saving and preserving the past done so we could remember him, and he could better remember himself, and try again?

Is it not the singularity of life that terrifies us? Is not the decisive difference between comedy and tragedy that tragedy denies us another chance? Shakespeare over and over demonstrates life’s singularity — the irrevocability of our decisions, hasty and even mad though they be. How solemn and huge and deeply pathetic our life does loom in its once-and doneness, how inexorably linear, even though our rotating, revolving planet offers us the cycles of the day and of the year to suggest that existence is intrinsically cyclical, a playful spin, and that there will always be, tomorrow morning or the next, another chance.

Solar Eclipse by Carleton Watkins – 1889. Prints.

Via: New Yorker, Brain Pickings.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.