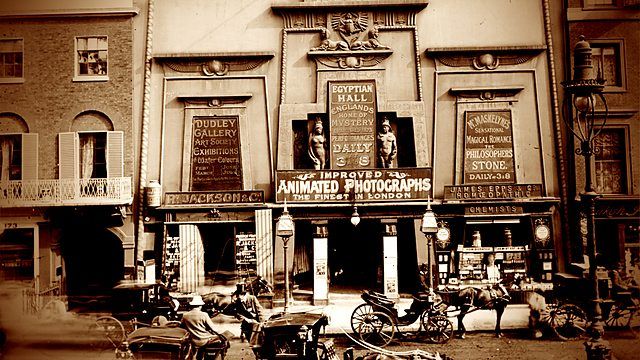

In August 1846, Joseph Faber, a German-born scientist and mathematician, stood in London’s Egyptian Hall. Punters paying the shilling entrance fee could see his Marvelous Talking Machine, an incredible contraption able to mimic human speech and ‘breathe’.

Faber had demonstrated his first talking machine in Vienna 1840 and to the King of Bavaria in 1841. In early 1844, Faber showcased a new improved version in New York City. People were non-plussed by it. So, in 1845 he tried again, exhibiting his machine in Philadelphia where Phineas T. Barnum witnessed it in 1846 and, under the name of the Euphonia, brought it to London.

Would it succeed is wowing people who loved the bizarre? As Liza Picard writes:

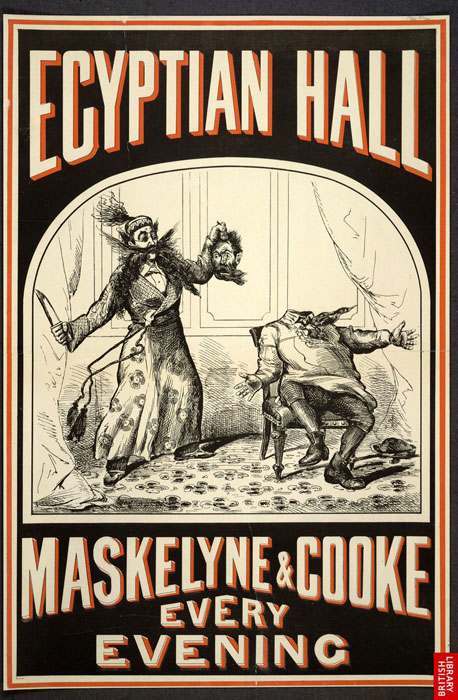

llusionists and spiritualists were popular attractions in theatres and exhibition halls: audiences could sit amazed as ghosts appeared on stage and automata solved mathematical puzzles. Renowned performers appeared to levitate, slice the heads off spectators and escape out of locked boxes.

This was pop culture. Punch magazine adds:

The walls of the Egyptian Hall in Piccadilly are placarded from top to bottom with bills announcing the exhibition of some frightful object within and the building itself will soon be known as the Hall of Ugliness. We cannot understand the cause of the now prevailing taste for deformity, which seems to grow by what it feeds upon. The first dose administered to this morbid appetite was somewhat homoeopathic, being comprised in the diminutive form of TOM THUMB; but the eagerness with which this little humbug was devoured – at least by female kisses – has caused the importation, on a much larger scale, of all sorts of lusus naturae and specimens of animated ugliness, which form a source of attraction to the public, and are exhibited with success in the very building where HAYDON in vain invited attention to the creations of his genius.

If Beauty and the Beast should be brought into competition in London, at the present day Beauty would stand no chance against the Beast in the race for popularity.

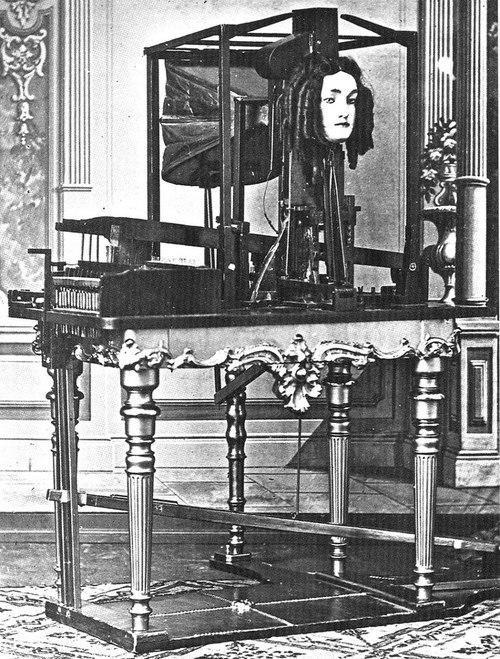

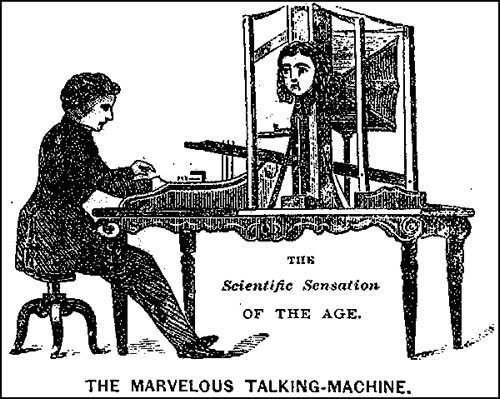

What about Beauty and the Beast in one hit? You see, stuck atop the Euphonia was a woman’s head. Not a real head. This was the likeness of a female noggin – its hair in ringlets, its eyes unblinking, its tongue rolling; a figurehead to a metal and wood body of 16 piano keys, bellows, an ivory reed and a seventeenth key that opened and closed the creature’s glottis.

Faber pressed the keys and pumped the bellows. The head awoke. The machine spoke:

“Please excuse my slow pronunciation… Good morning, ladies and gentlemen… It is a warm day… It is a rainy day… Bongiorno, signori.”

Euphonia then aired a rendition of God Save the Queen.

A definition of the medical term “euphonia” is the condition of having a normal clear voice. But there was nothing normal about this machine. This was a rubber-faced ventriloquist’s dummy with ideas and volition. It was an intimidating sight.

The Times’ man on the scene was impressed with the Euphonia, calling it “almost a duty of all who can afford to see it, to gratify at once their curiosity, and show their encouragement of genius.”

But the crowds never flocked to see the thing. Why not?

Theater manager John Hollingshead offers us a clue, noting in My Lifetime (1895):

The Professor was not too clean, and his hair and beard sadly wanted the attention of a barber. I have no doubt that he slept in the same room as his figure—his scientific Frankenstein monster—and I felt the secret influence of an idea that the two were destined to live and die together… One keyboard, touched by the Professor, produced words which, slowly and deliberately in a hoarse sepulchral voice came from the mouth of the figure, as if from the depths of a tomb.

Just one year prior to the Euphonia’s London debut, influential scientist and director of the Smithsonian Institute Joseph Henry had raved about its possible applications. Henry envisioned linking two Euphonias together via telegraph line so that one might read aloud a telegram sent by the other, essentially forming a convoluted telephone. (Imagine if, years later, instead of backing a young, nervous inventor named Alexander Graham Bell, Henry had pursued the Euphonia. Would every home in America be outfitted with a dead-eyed animatronic face that read electronic messages aloud in a ghostly whisper?)

Addison Nugent has a theory:

The answer may lie in a thought experiment put forth by the roboticist Mashahiro Mori in 1970. Mori proposed that “as [a] robot became more human-like there would first be an increase in its acceptability and then as it approached a nearly human state there would be a dramatic decrease in acceptance.” This dip in public approval represents a Goldilocks zone for robotic anthropomorphism: Robots who find themselves in it are simultaneously too human and not human enough. Faber’s Euphonia seemed to have gotten lost somewhere in what Mori called “the Uncanny Valley”…

Sigmund Freud defined the uncanny as “that class of terrifying which leads back to something long known to us, once very familiar.”

(The Uncanny Valley has been used in reference to The Turk, a chess-playing automaton made by Wolfgang von Kempelen (1734-1804). The Turk is believed to have been an elaborate hoax with a legless chess-playing human occupying its innards. To Faber, Kempelen was an inspiration, sparking the young German’s interest in ‘robotics’ though a Speaking Machine and his book On the Mechanism of Human Speech.

What happened next to Faber is unclear. Some say he committed suicide around 1850 after destroying the last Euphonia. Newspaper reports held at the British Library say Faber died in the 1860s, at which point the Euphonia was passed down to his niece, whose husband fashioned himself “Professor Faber”. It continued to be exhibited in Paris and London until 1885.

And after that? We don’t know. But if ever you should hear a piece of technology with a human face singing and commenting on the weather, don’t be afraid. That’s just Faber’s legacy on your smartphone…

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.