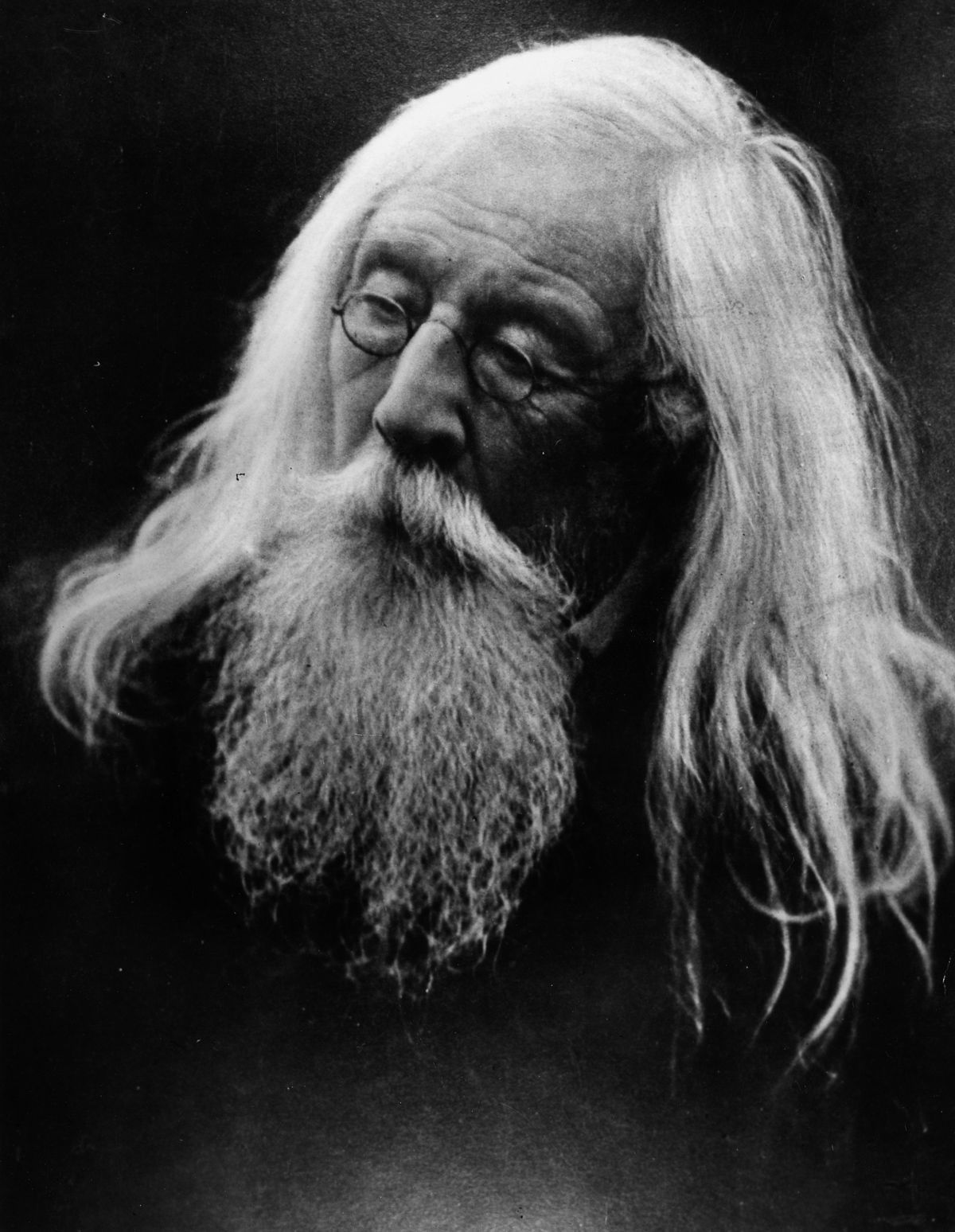

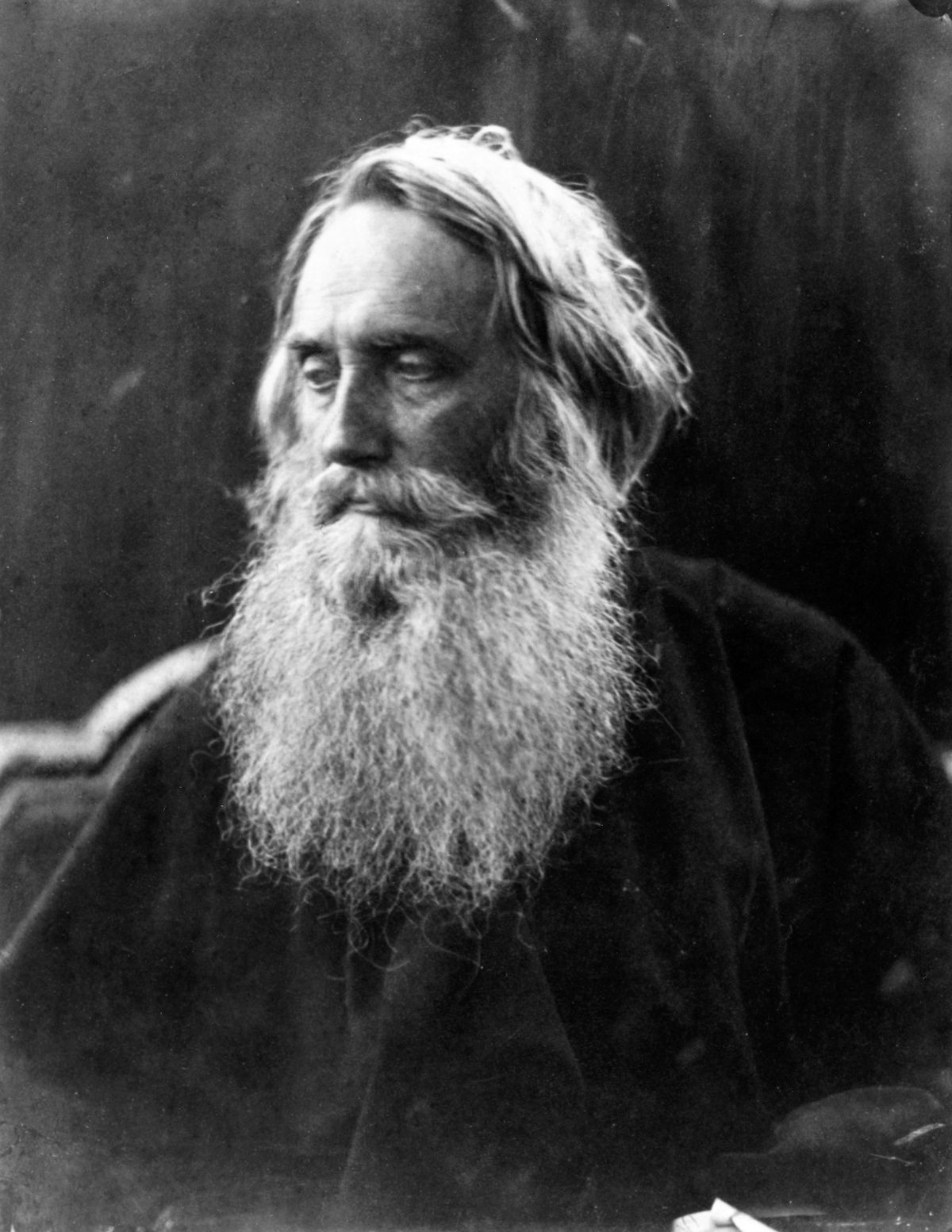

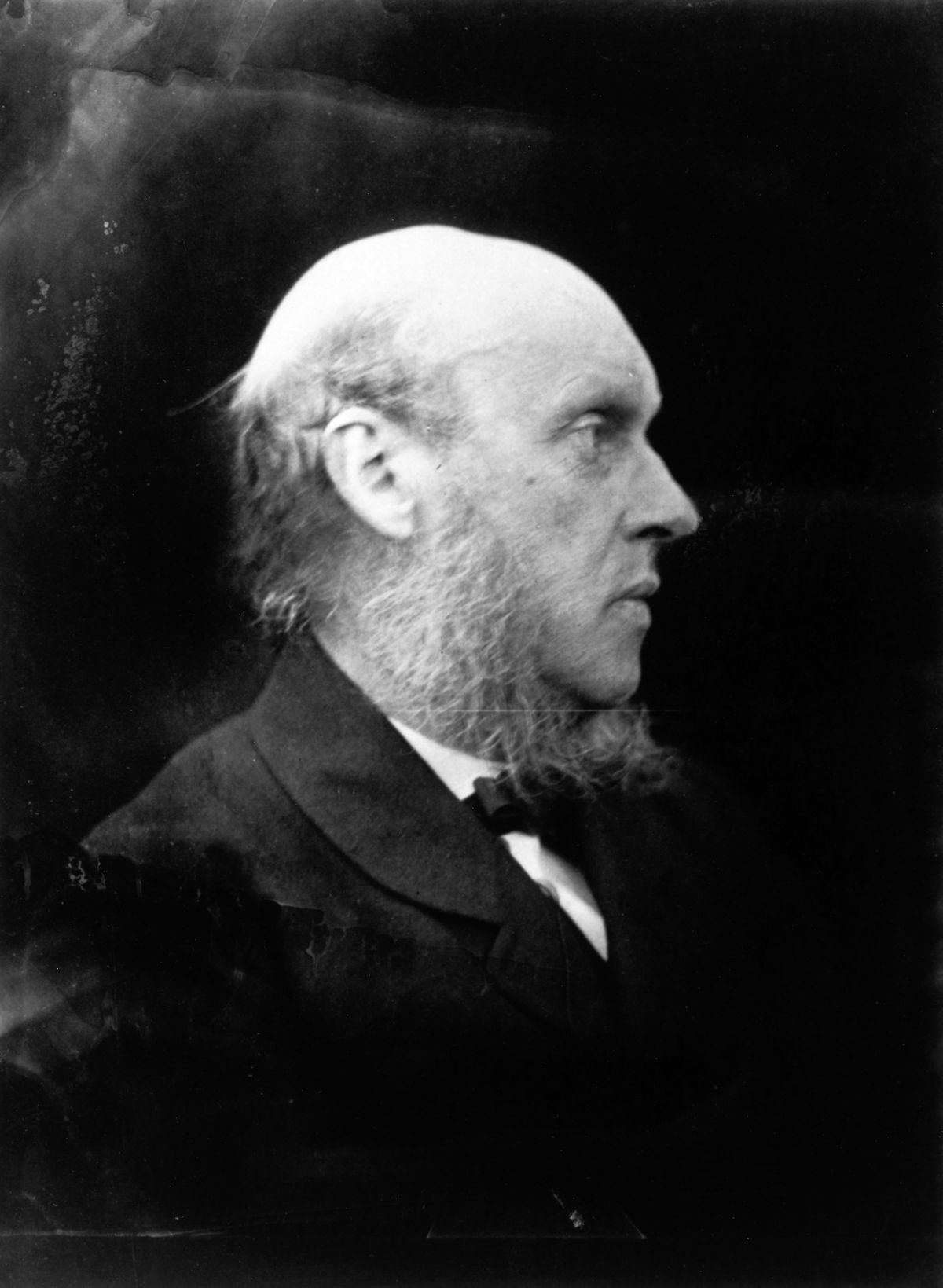

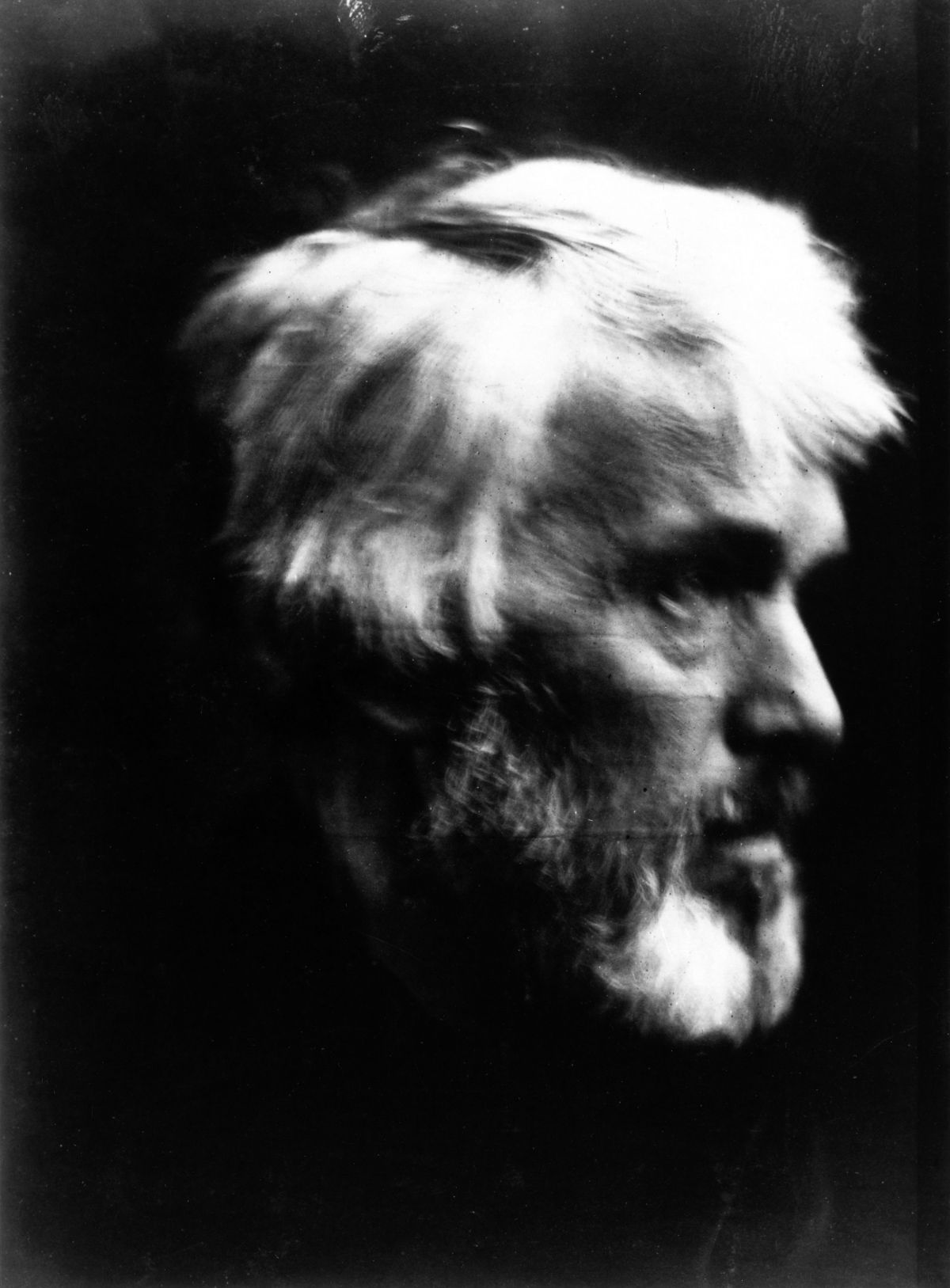

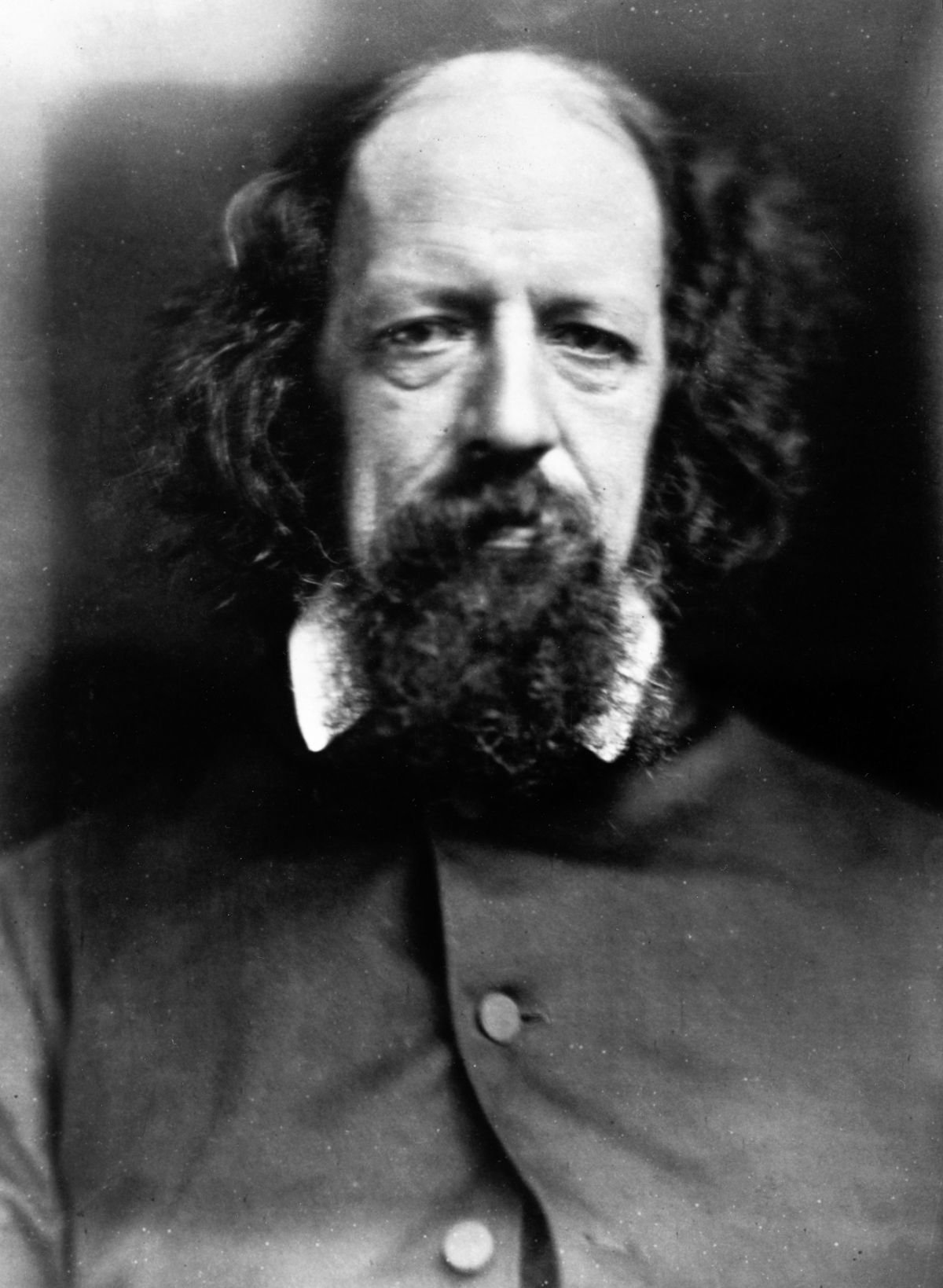

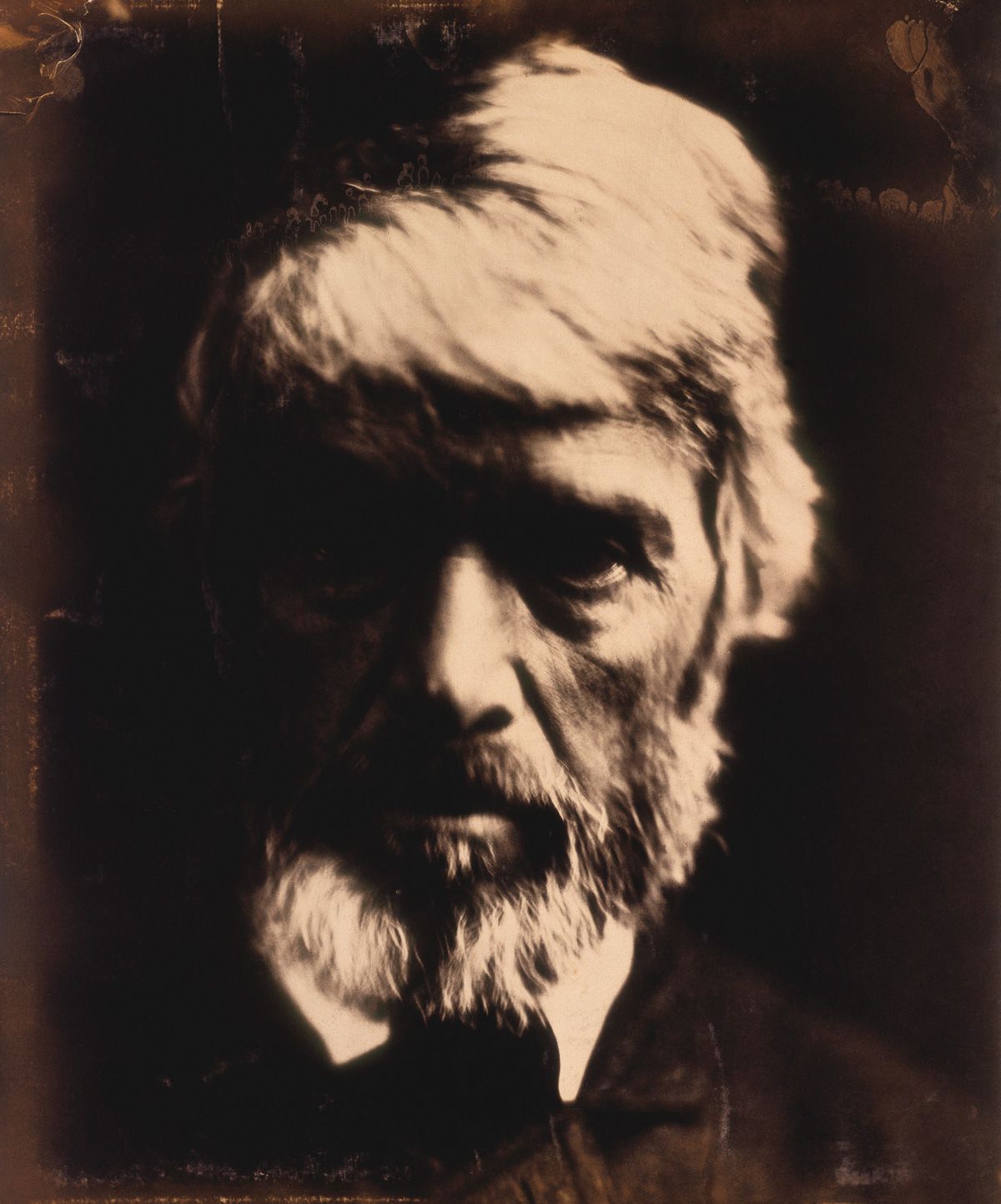

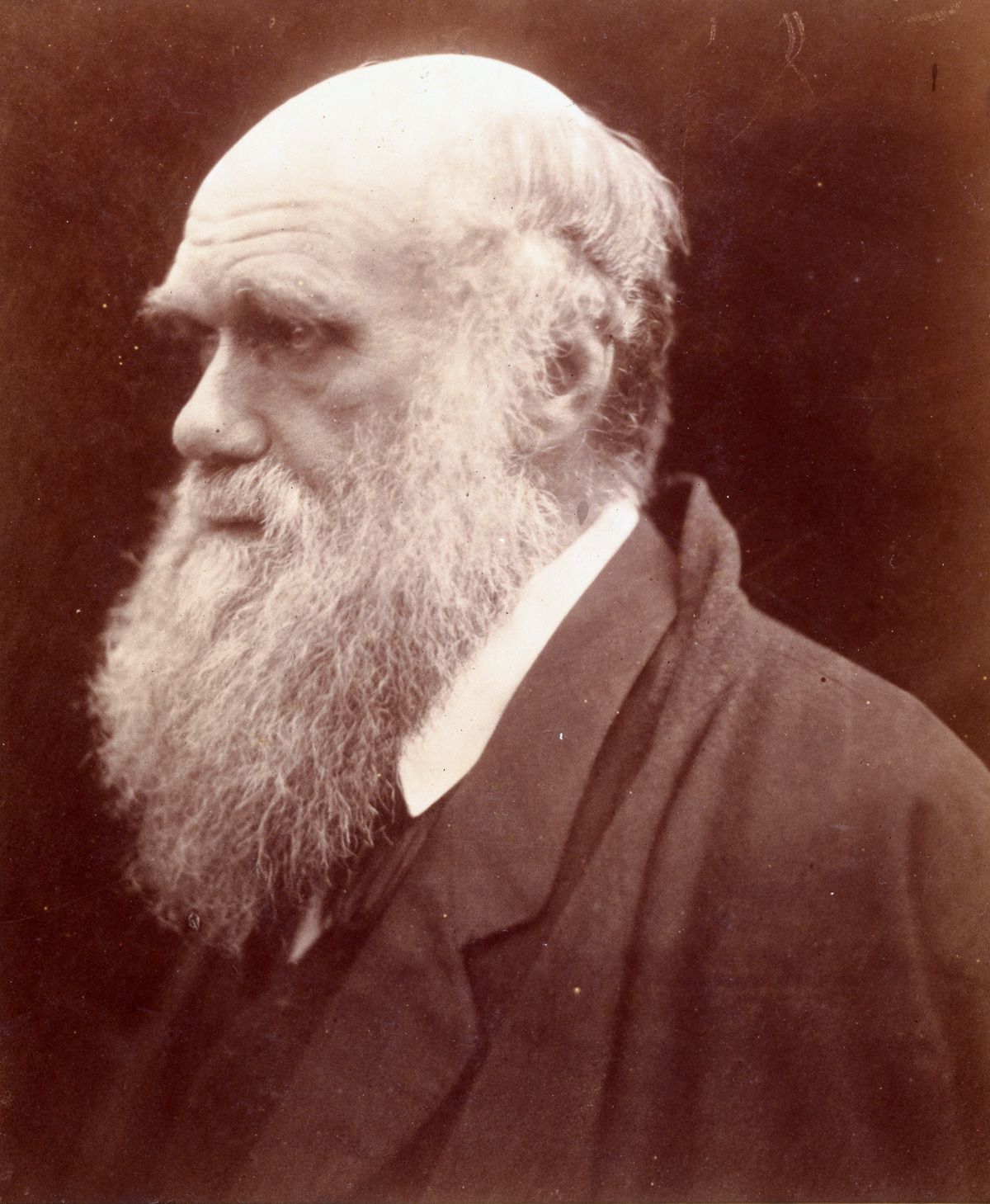

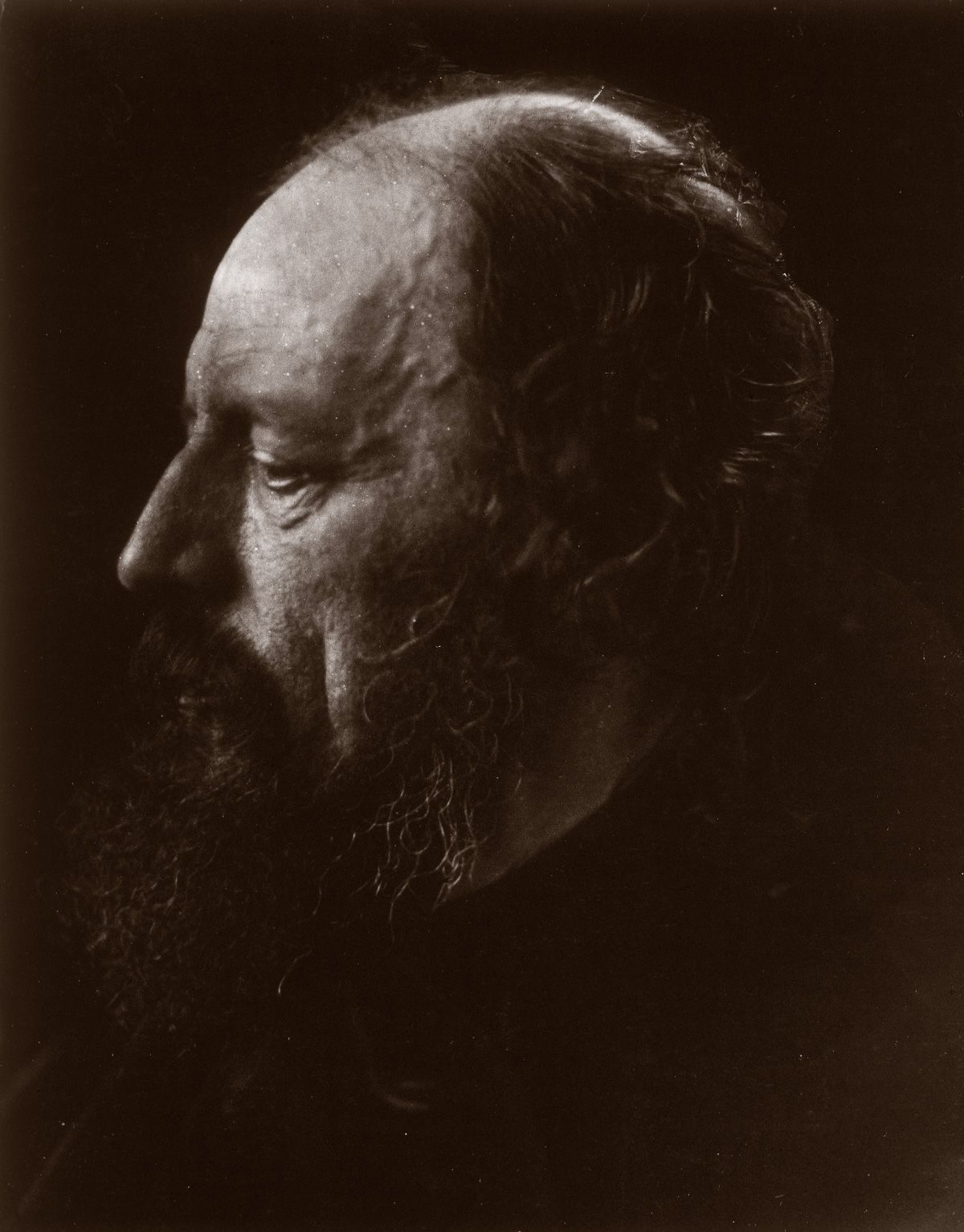

Indian-born ethnic and cultural Englishwoman Julia Margaret Cameron (1815-1879) began to experiment in photographic portraiture after receiving a camera as a 48th birthday present from her daughter and son-in-law. Connected to the era’s notables – relocated from the colonies Cameron lived at the family’s estate on the Isle of Wight (named Dimbola Lodge after one of their Ceylon rubber and coffee plantations), her home neighboured that of long-time pal Alfred Lord Tennyson, the country’s hymned Poet Laureate – many famous faces became Cameron’s subjects.

One of her subjects, Sir John Herschel, coined the very word ‘photography’, noting in a letter to inventor Henry Fox Talbot of February 28, 1839, that the term “photogeny” was infected with poetic deficiencies: “It also lends itself to no inflexions & is not analogous with Litho & Chalcography.” Herschel suggested “photography”. Talbot agreed. On March 12, the word was heard for the first time when Talbot presented his paper Note on the Art of Photography or the Application of the Chemical Rays of Light to the Purposes of Pictorial Representation to the Royal Society.

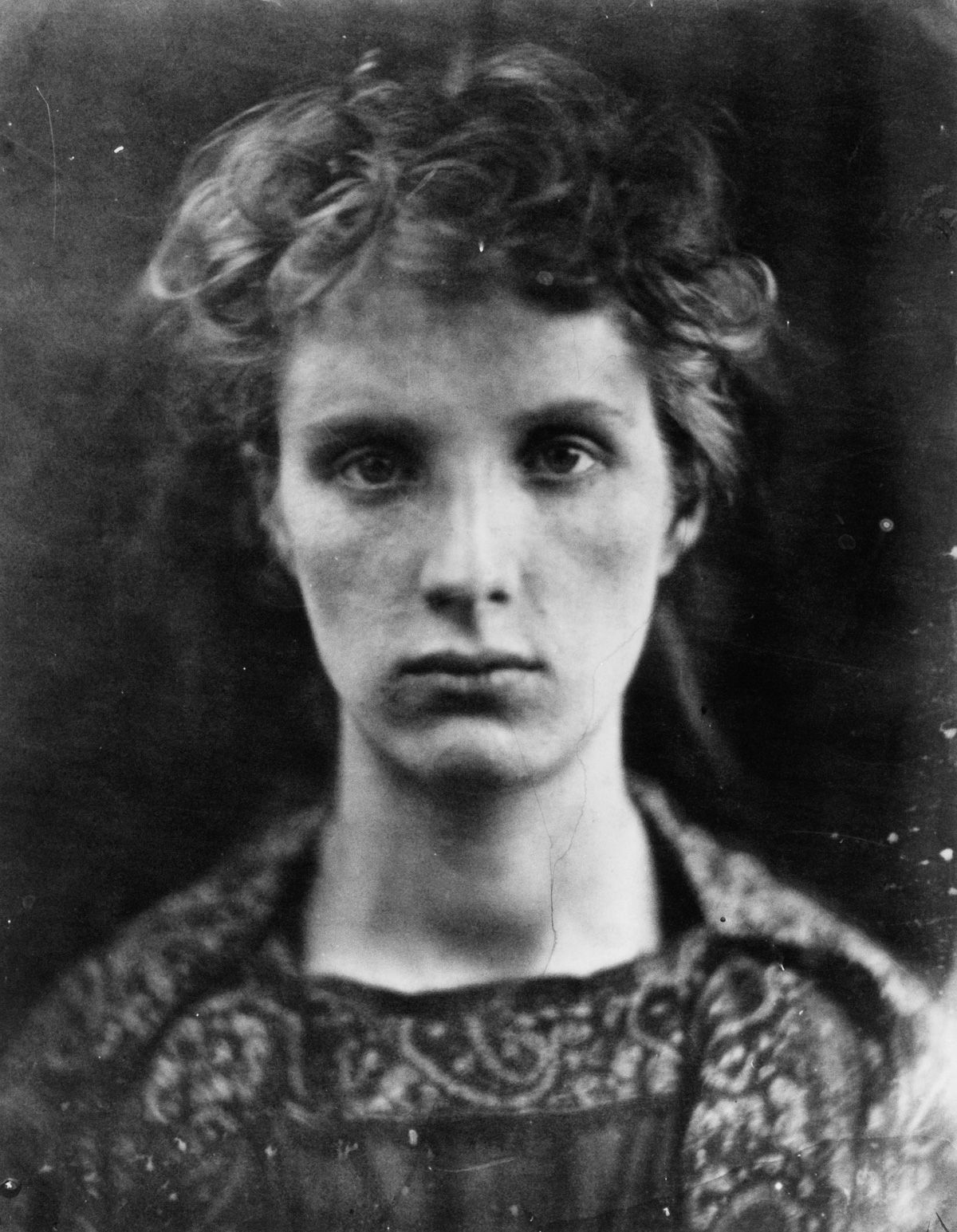

An 1866 review in MacMillan’s Magazine noted that her “position in literary and artistic society gives her the pick of the most beautiful and intellectual heads in the world”. If the intelligentsia weren’t about, she ordered the staff to sit. The process took hours. Tennyson cast Cameron’s subjects as “victims”.

In 1926, Virginia Woolf – Cameron was first cousins with the writer’s mother – published a posthumous volume of Cameron’s images under her Hogarth Press brand. (Woolf wrote the forward to Victorian Photographs of Famous Men and Fair Women).

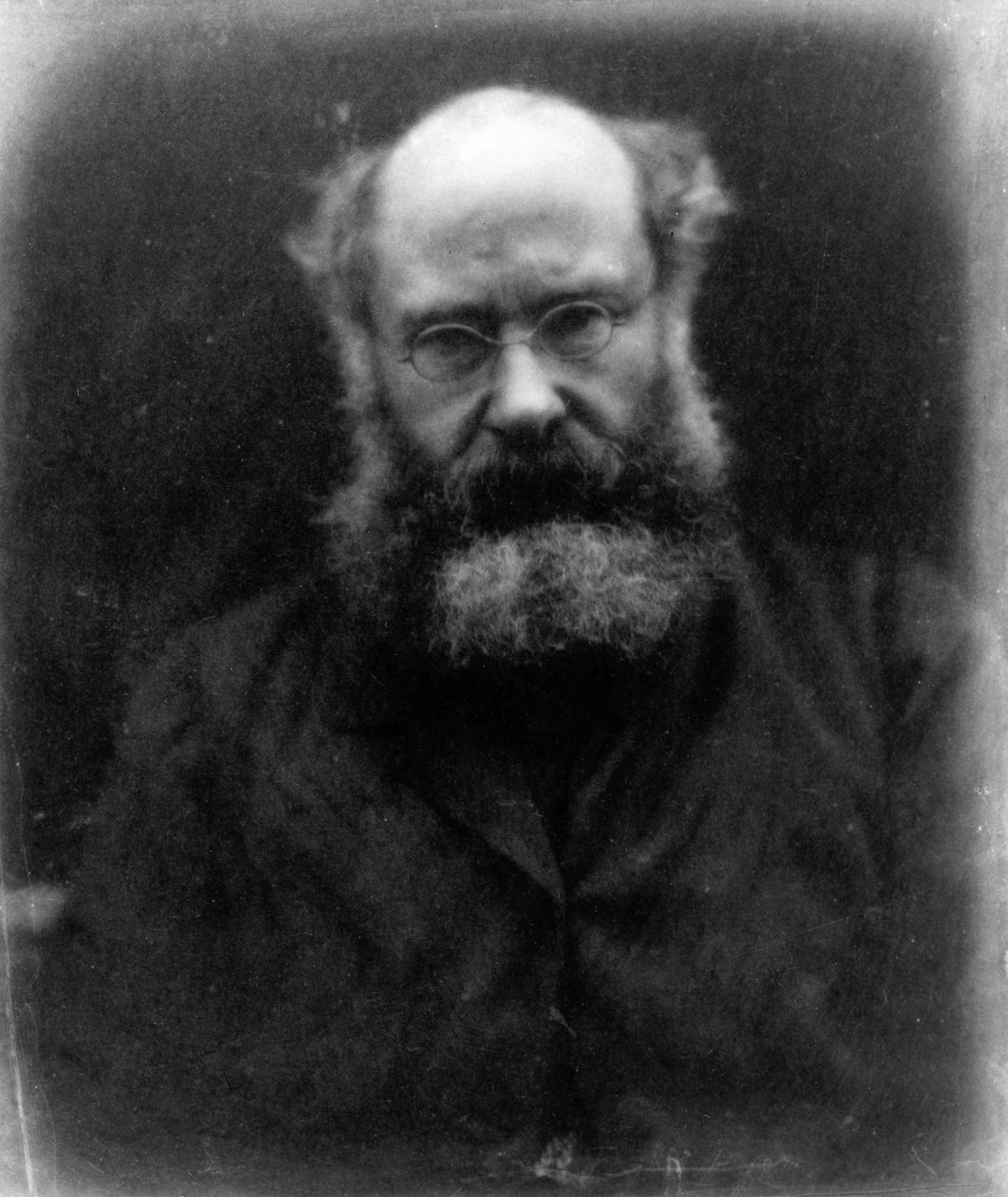

Nowadays Cameron’s work is routinely hailed as ‘pioneering’, involving as it did new techniques and products (and the large sums of money to fund it). It’s very much of the avant-garde. Images are lush and infused with mood. The flaws and smudges save the portraits from slipping into sentimentality, a condition inmate to those drippy pre-Raphaelites whose fussy work and hankering for bygone perfection Cameron adored. These intensely observant portraits look modern and insightful. Technology wasn’t an industrial purge on intelligence and sensitivity after all. It just let people do things differently.

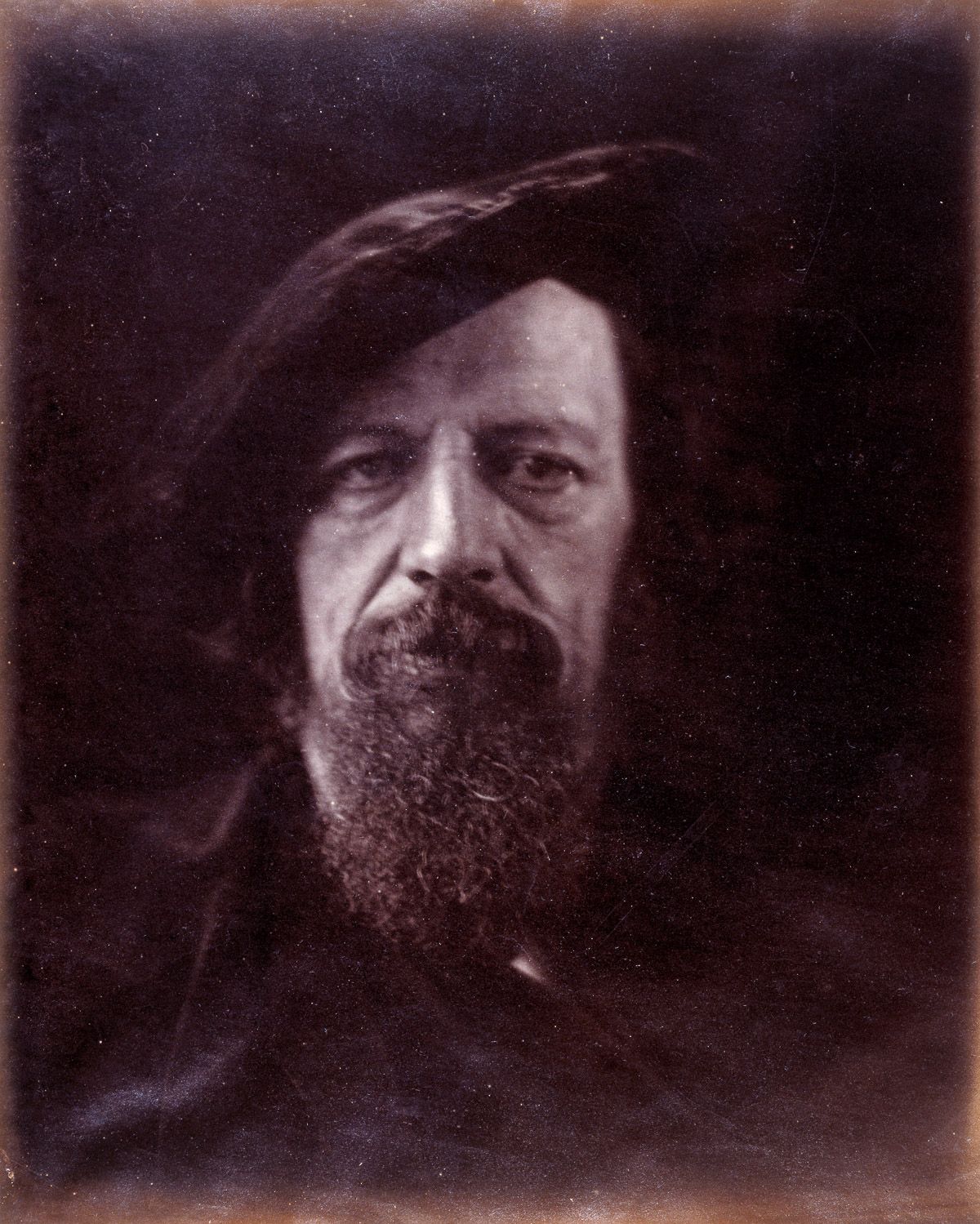

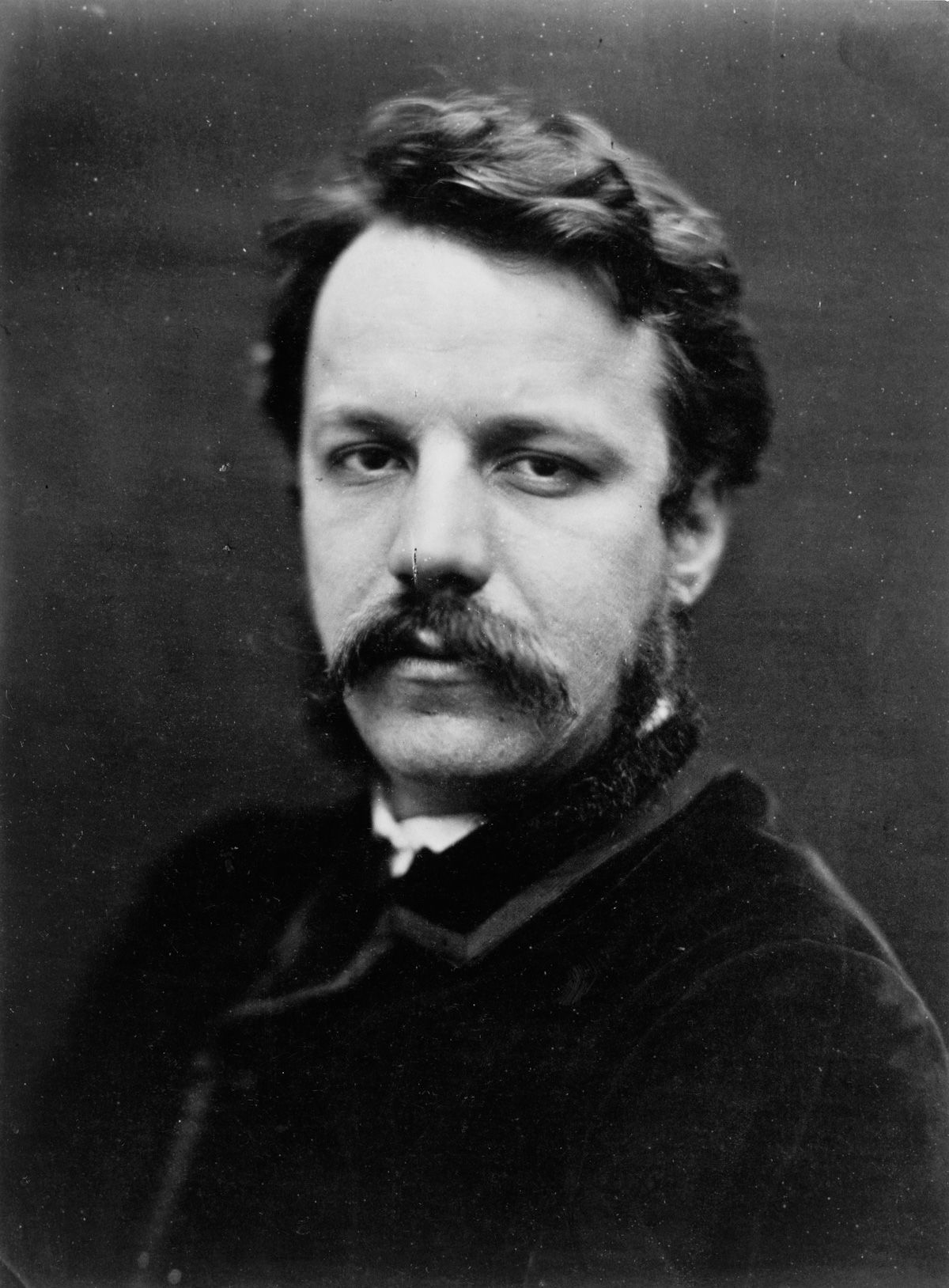

1867 A portrait of an Italian man, possibly an artist’s model called Alessandro Colorossi. This was Cameron’s only photo of a professional model. His son posed for the statue ‘Anteros’ (now simply known as Eros) in Piccadilly Circus, London.

“When focussing and coming to something which, to my eye, was very beautiful, I stopped there instead of screwing on the lens to the more definite focus which all other photographers insist upon.”

– Julie Margaret Cameron

Writing in MacMillan’s Magazine in 1866, critic Coventry Patmore declared that Cameron was ‘the first person who had the wit to see her mistakes were her successes, and henceforward to make her portraits systematically out of focus.’ In addition to pioneering soft focus, Cameron included in her photographs imperfections that other photographers would have rejected as technical flaws such as streaks, swirls and even fingerprints. Although criticised at the time as evidence of ‘slovenly’ technique, these traces of the artist’s hand in Cameron’s prints can now be appreciated for their modernity.

– V&A

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.