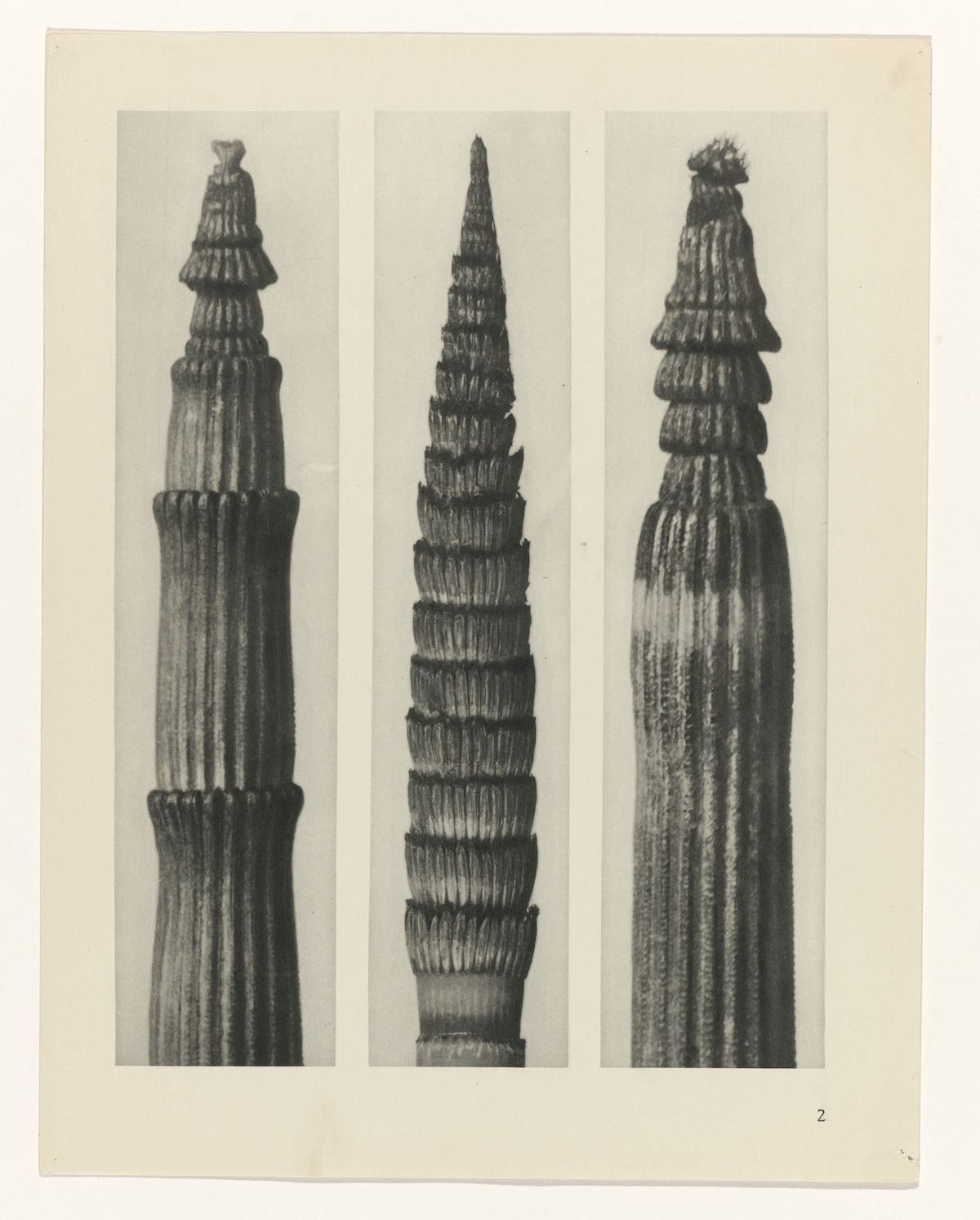

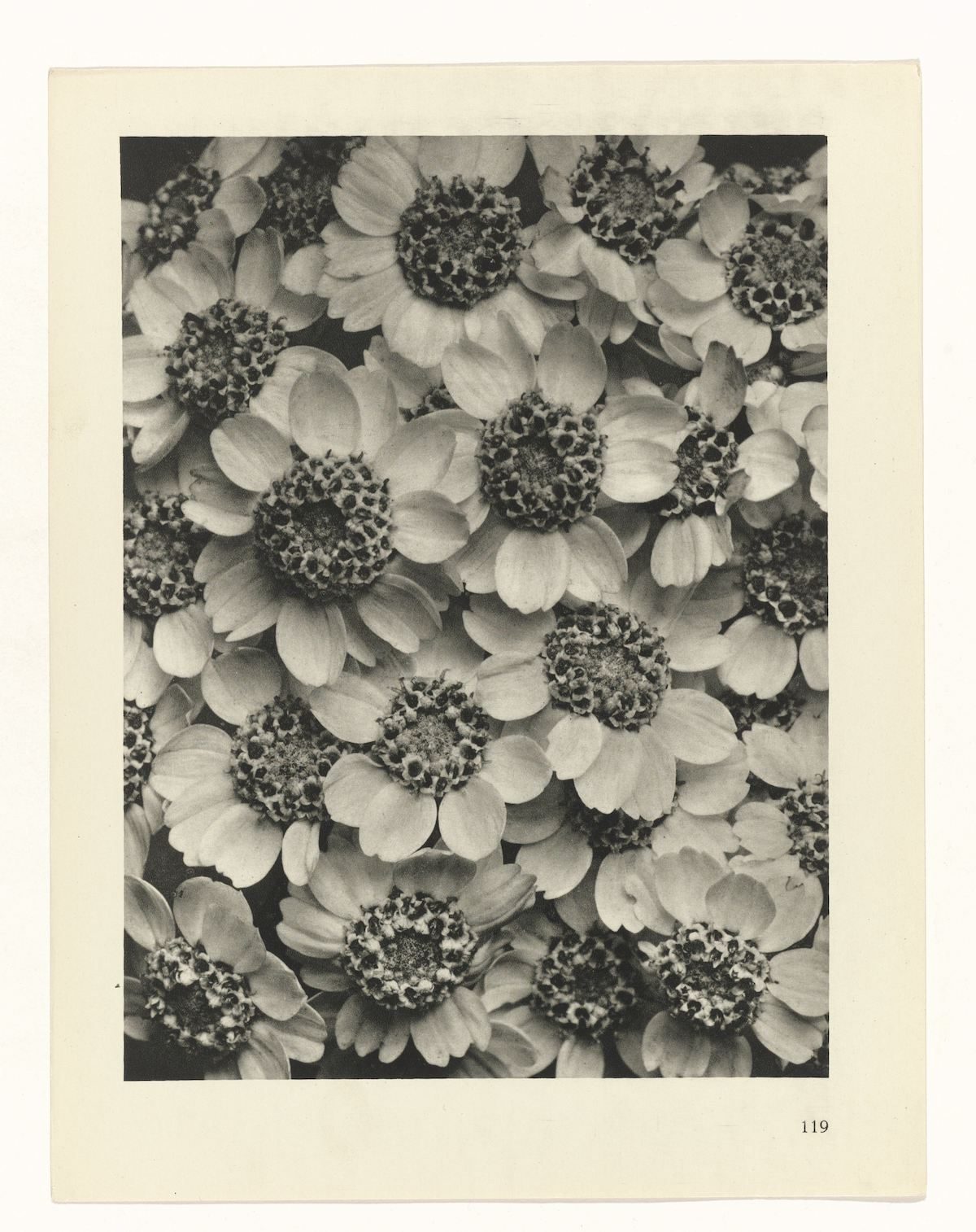

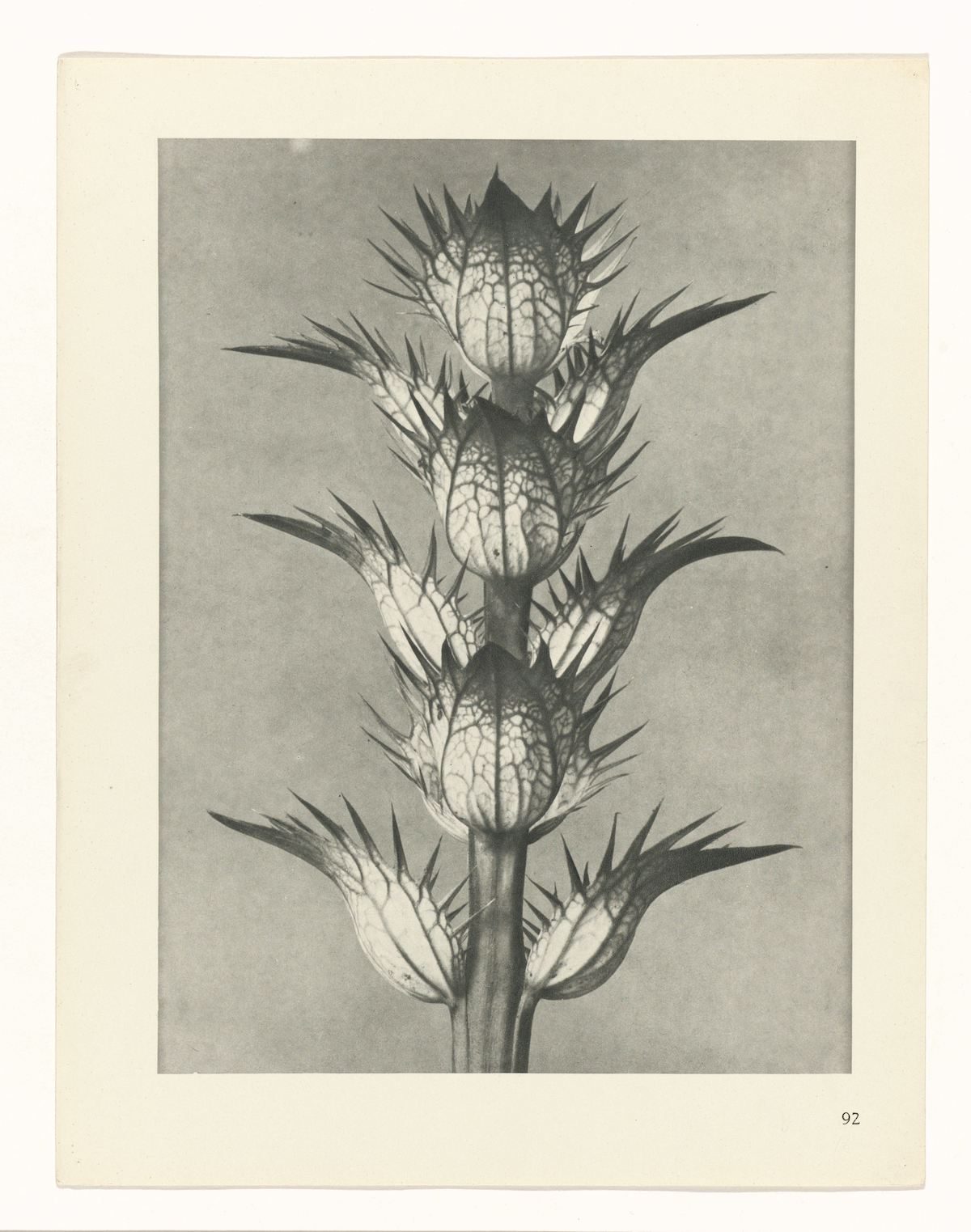

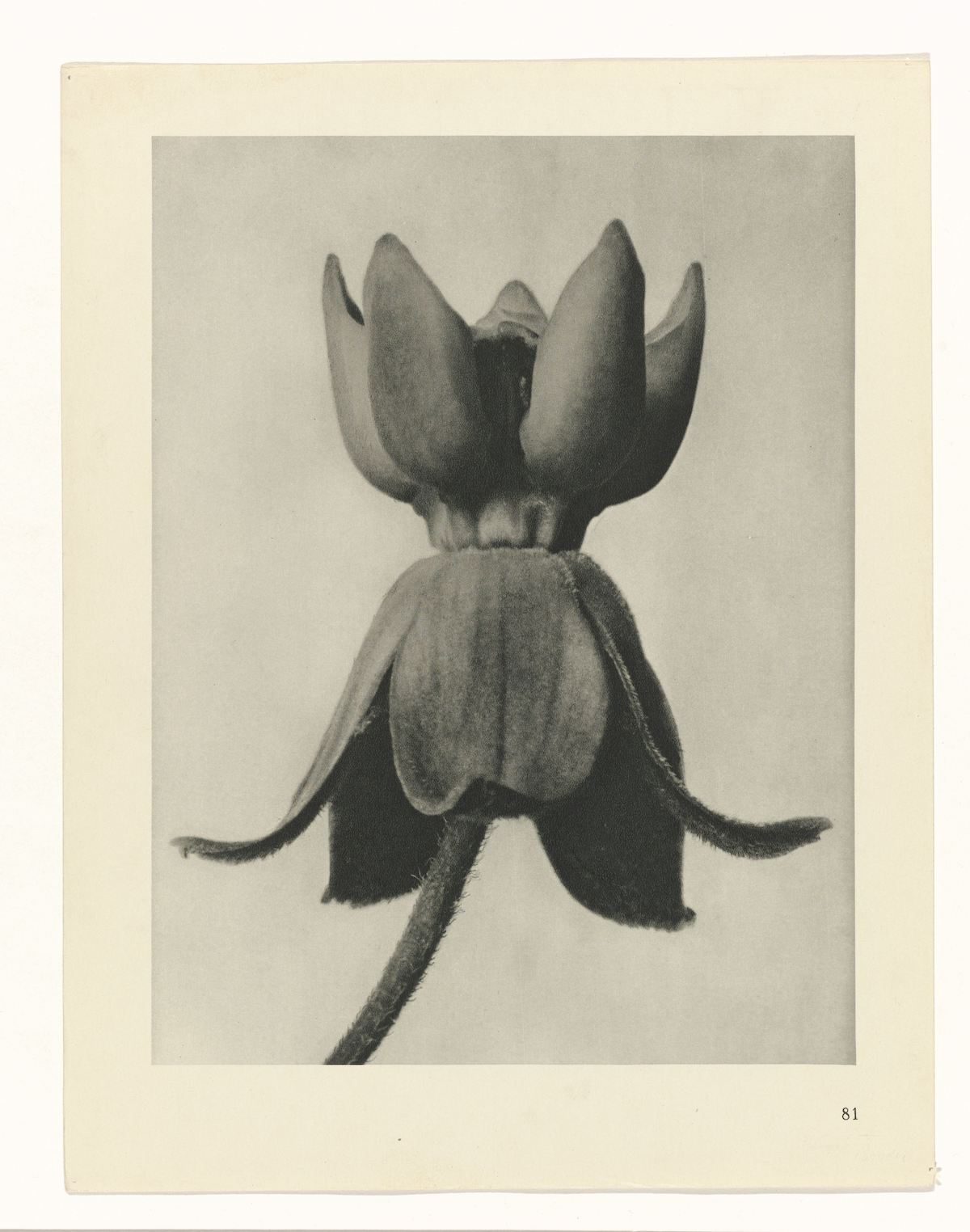

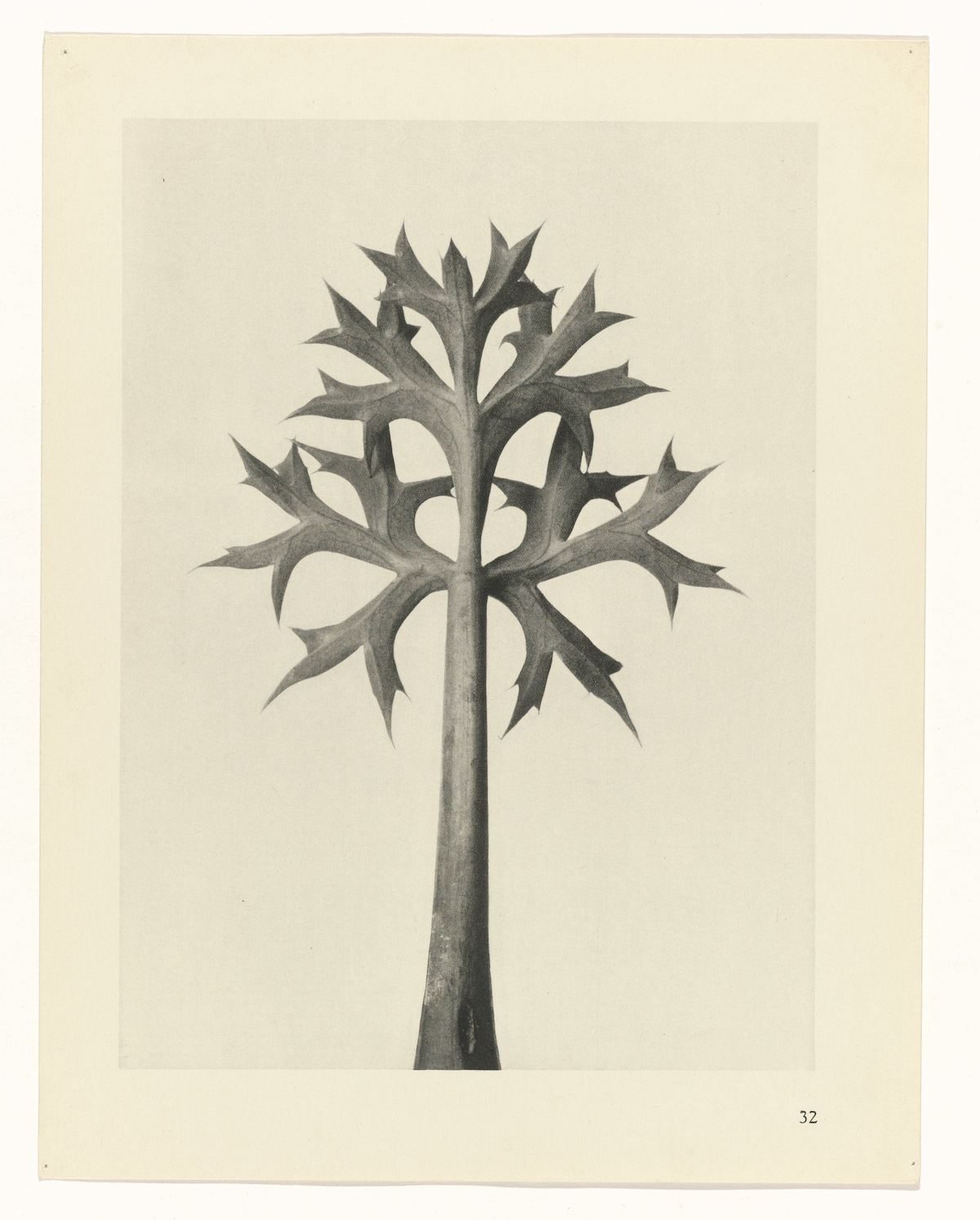

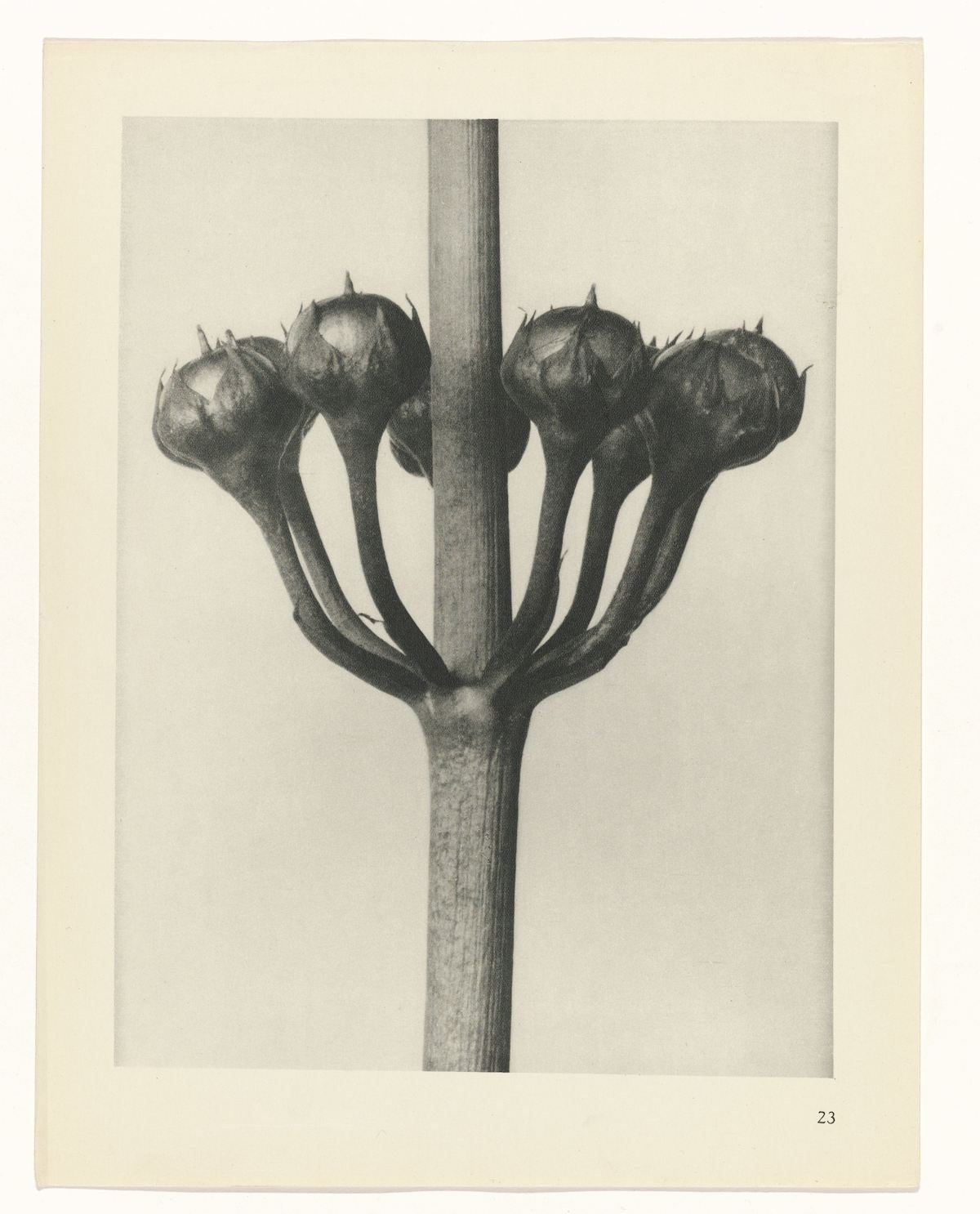

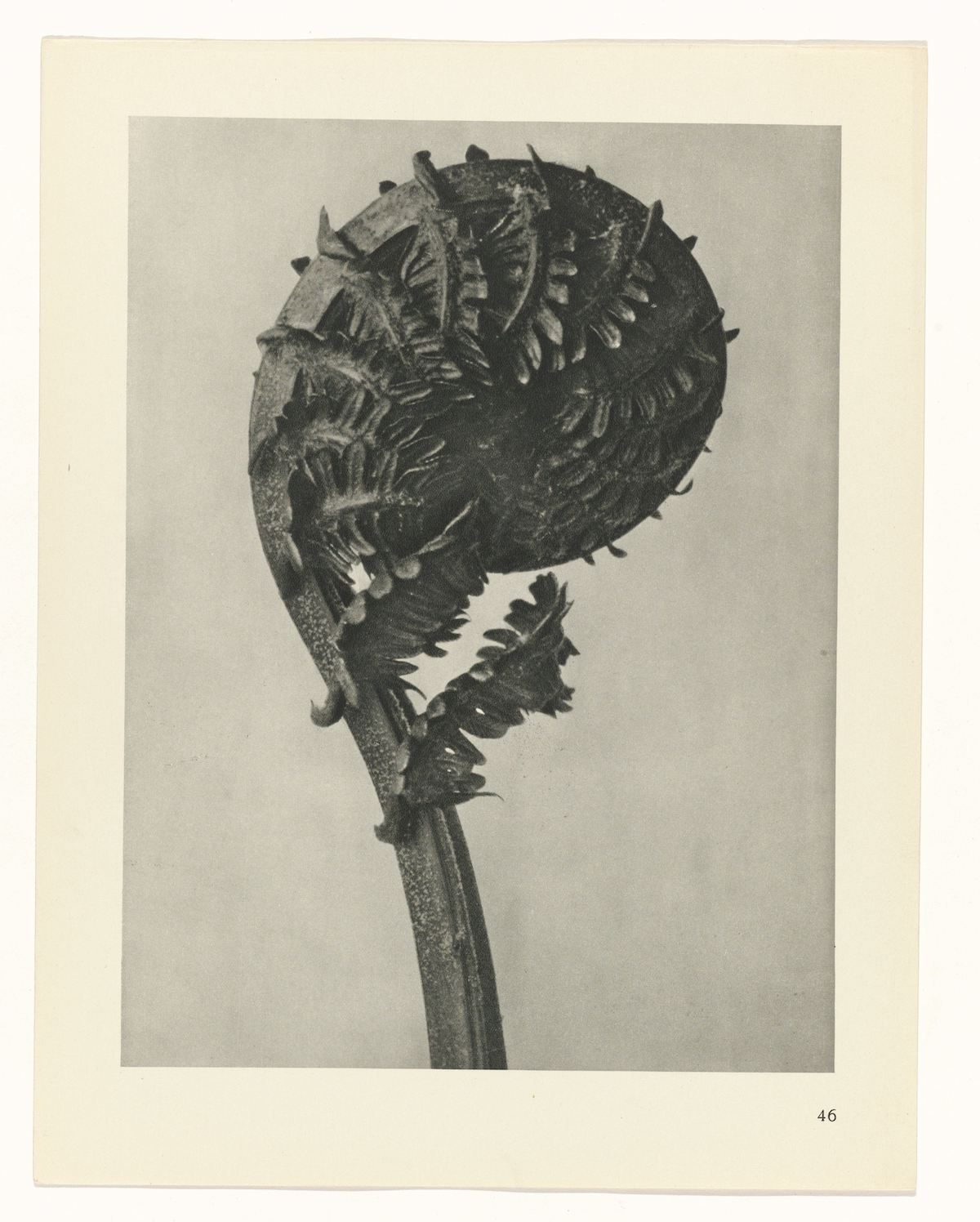

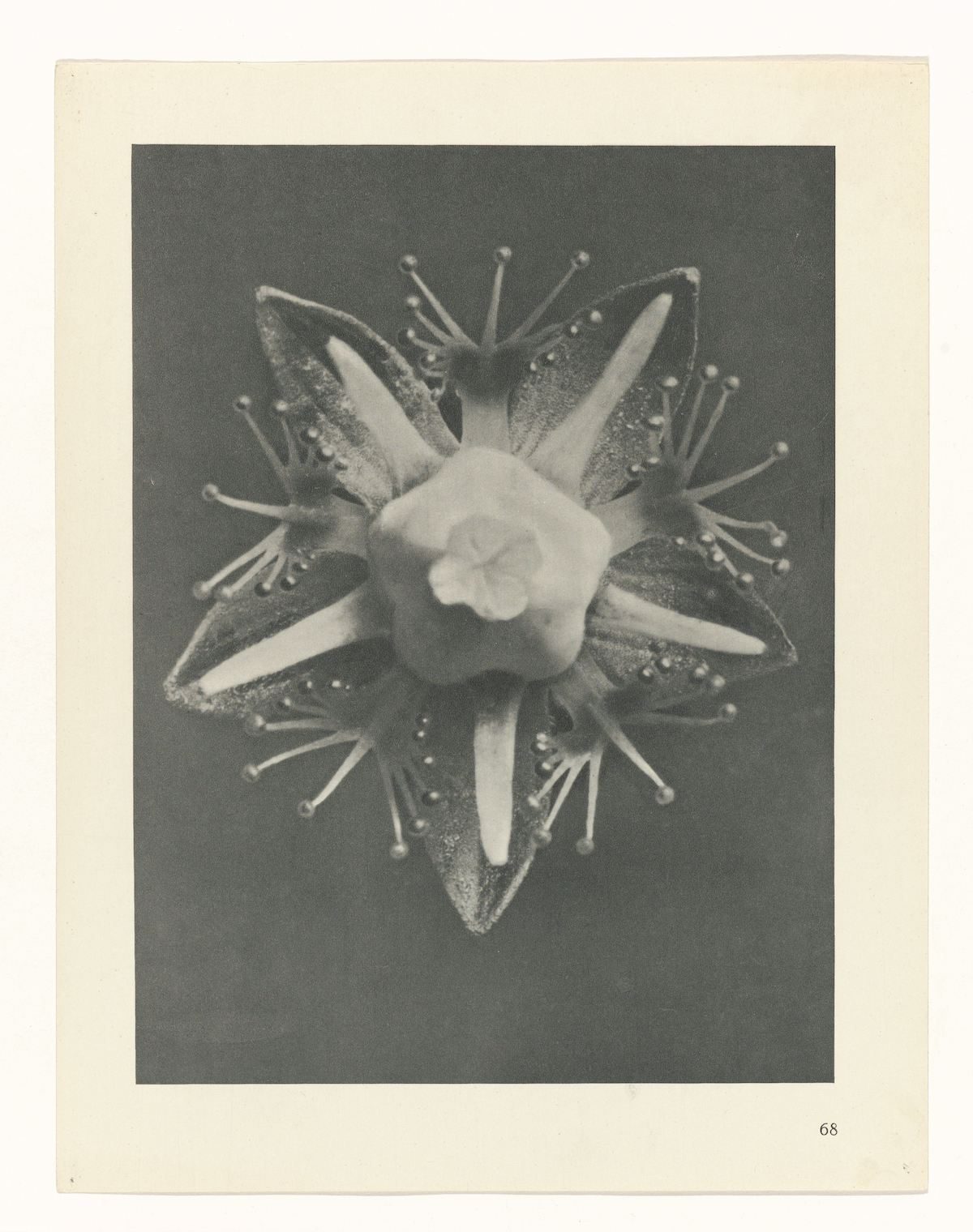

“If I give someone a horsetail he will have no difficulty making a photographic enlargement of it – anyone can do that. But to observe it, to notice and discover its forms, is something that only a few are capable of.”

– Karl Blossfeldt, Urformen der Kunst (Art Forms in Nature)

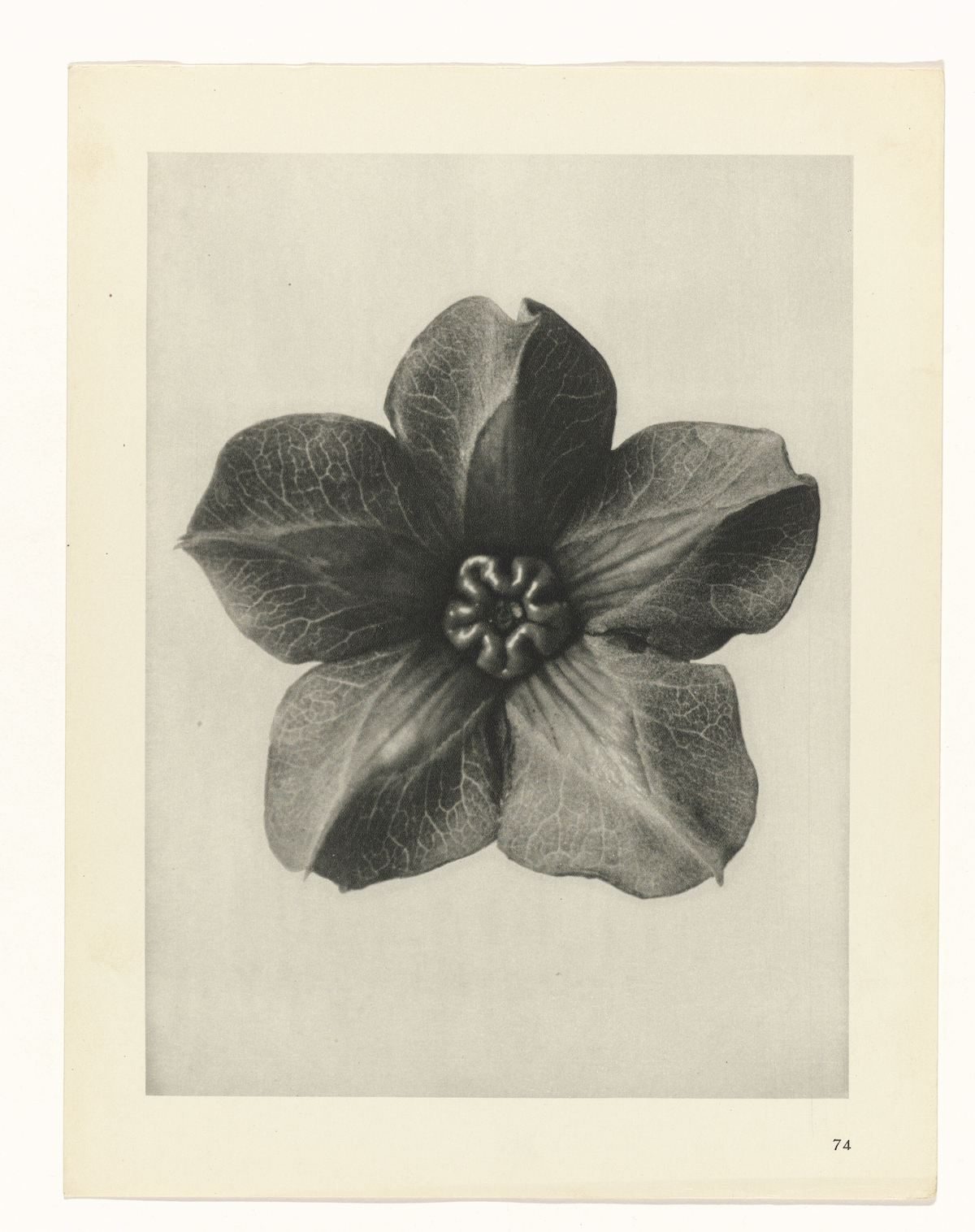

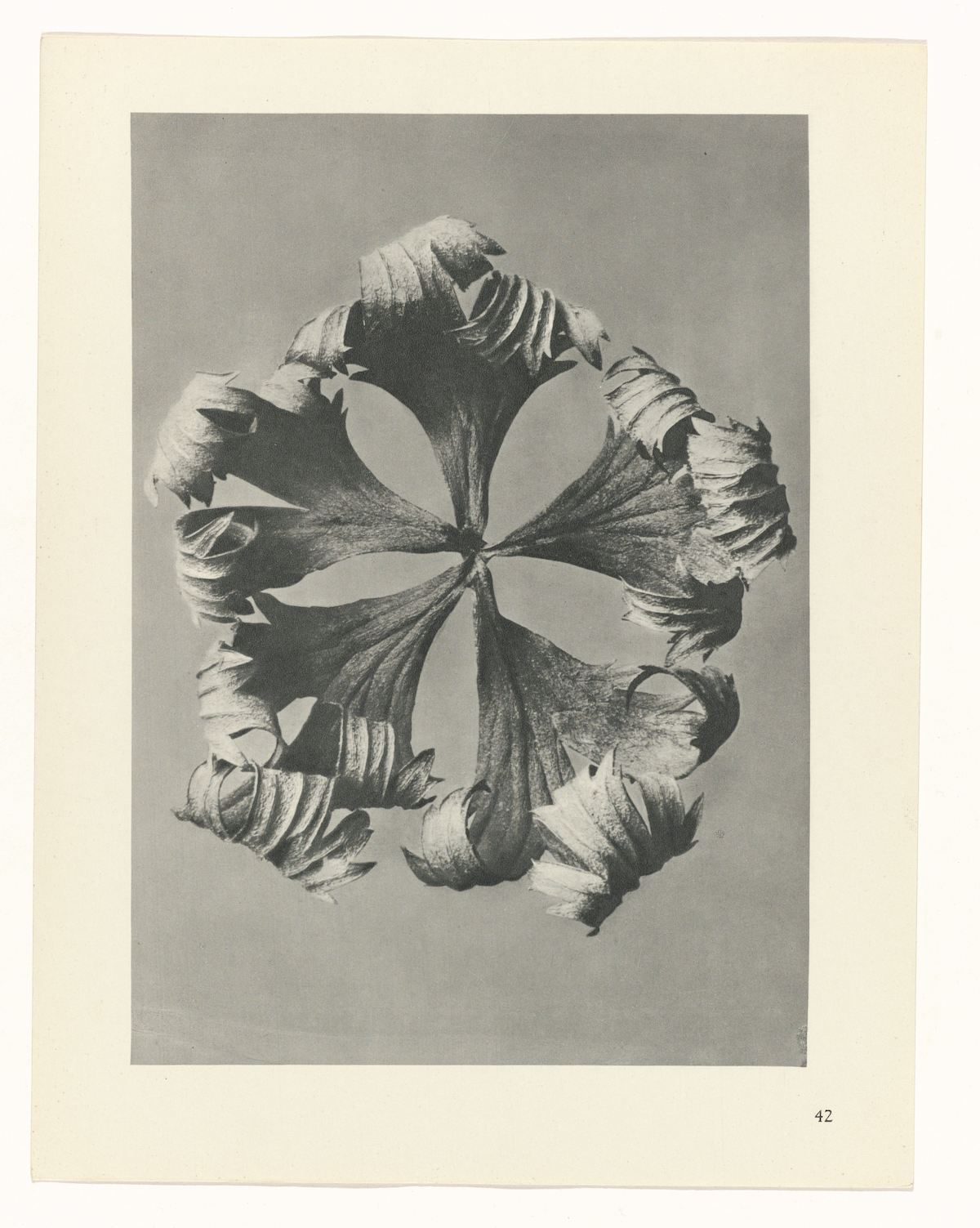

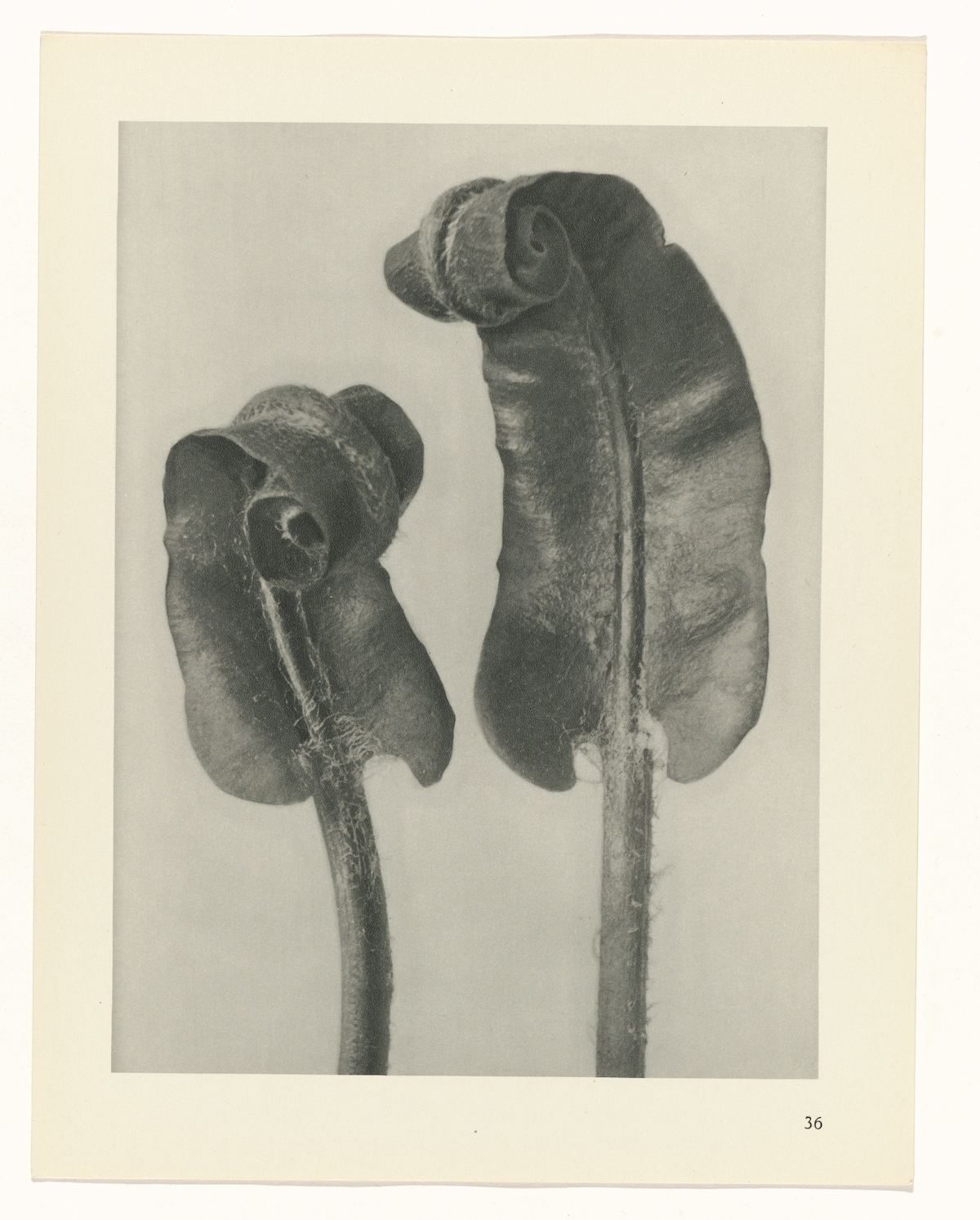

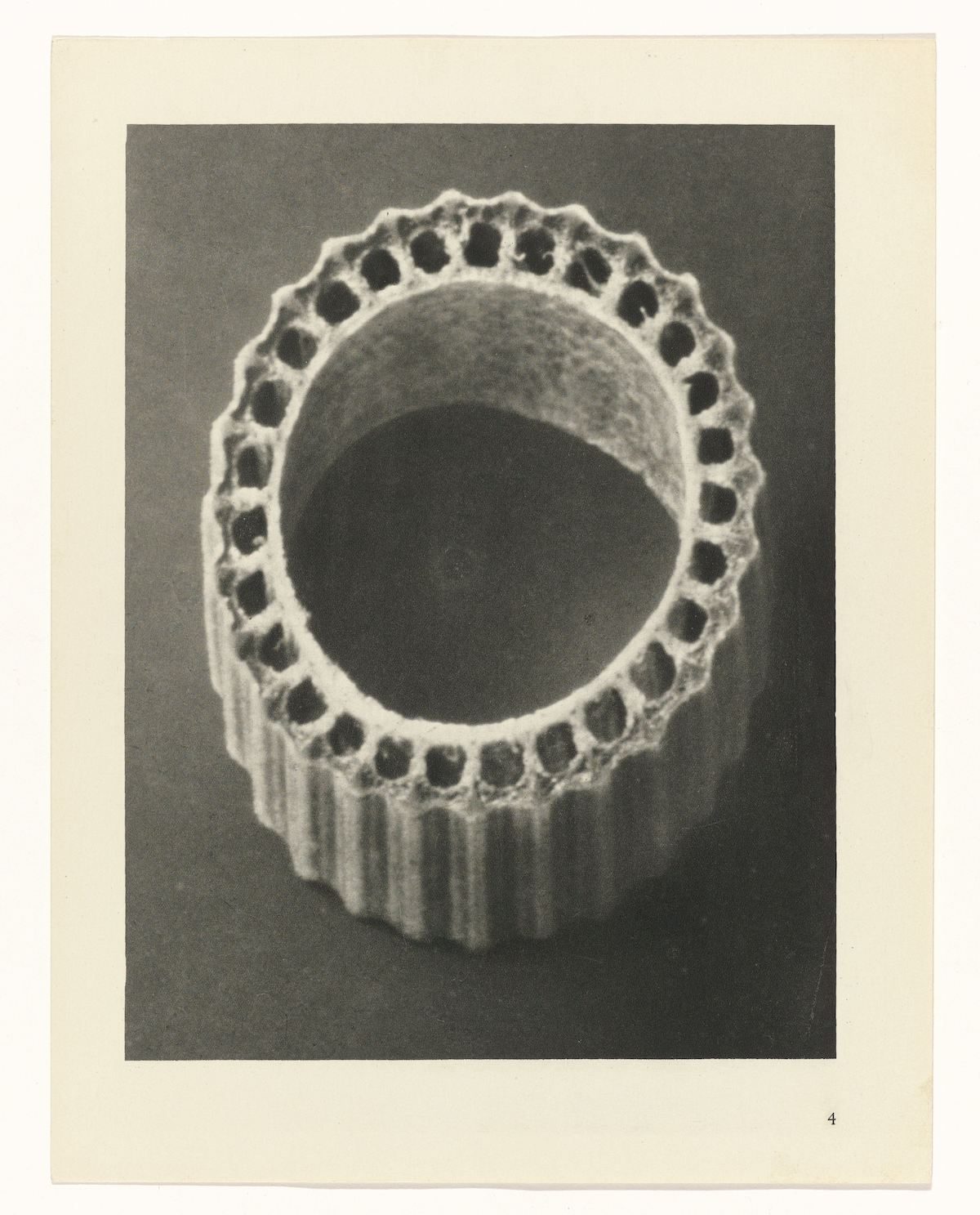

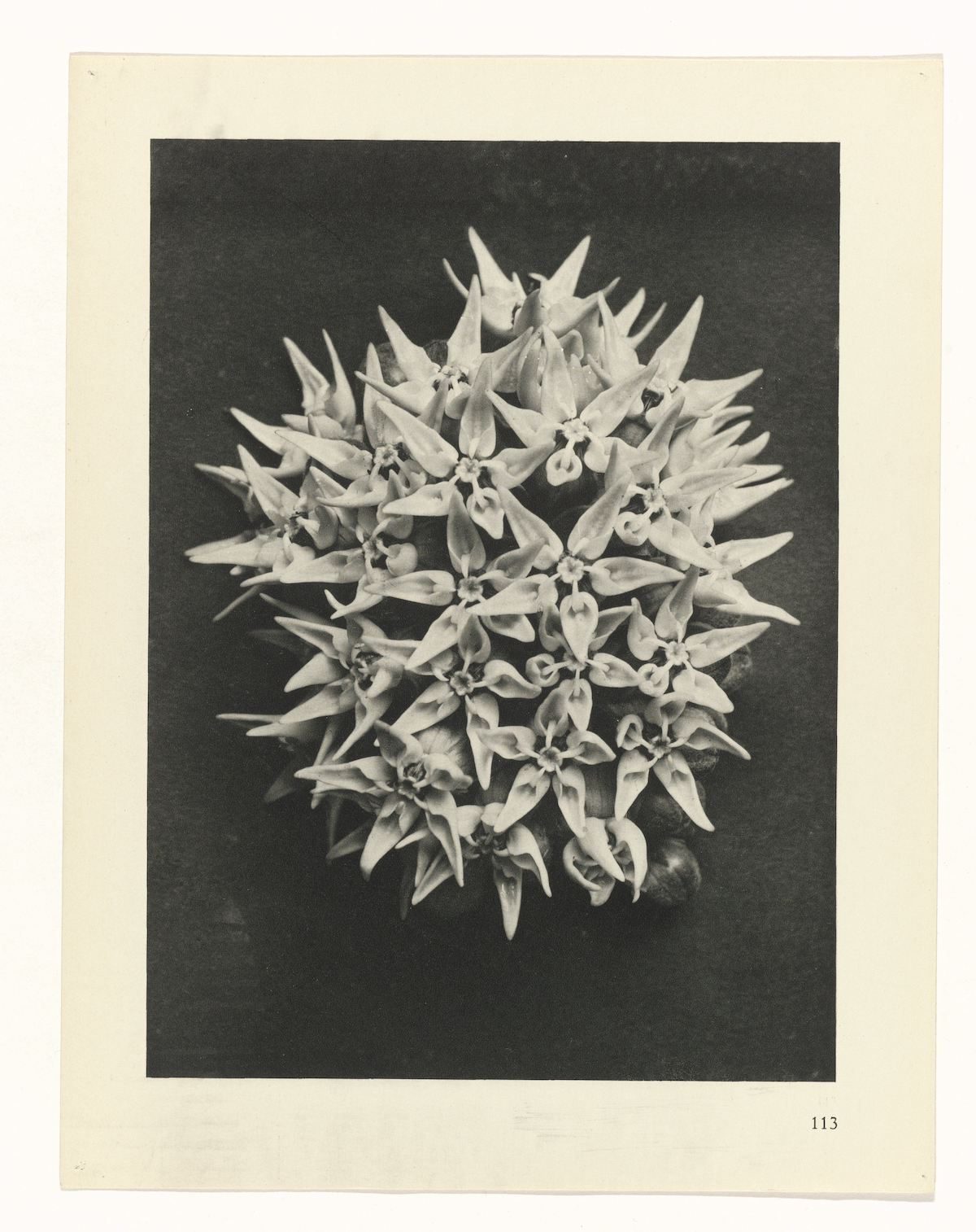

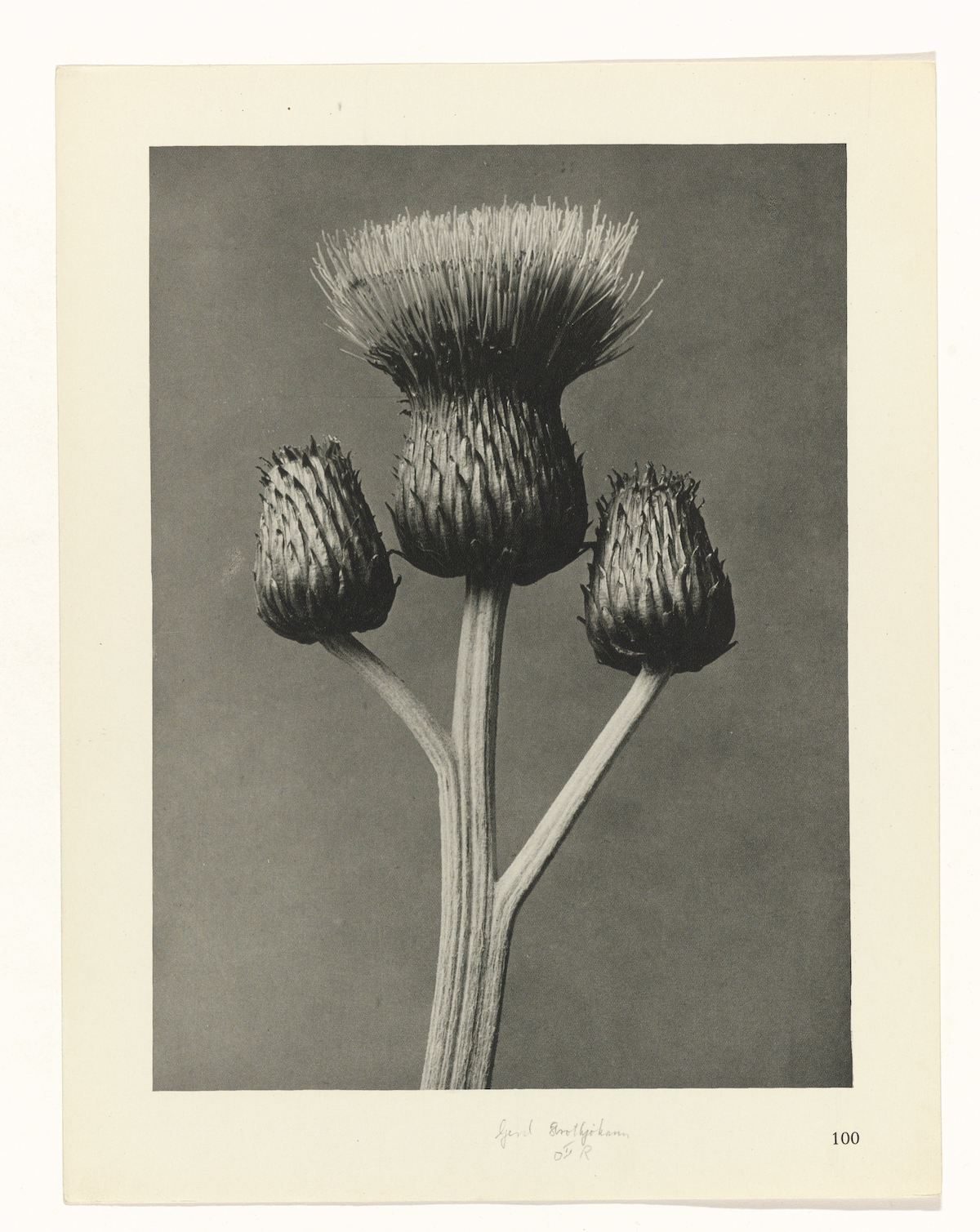

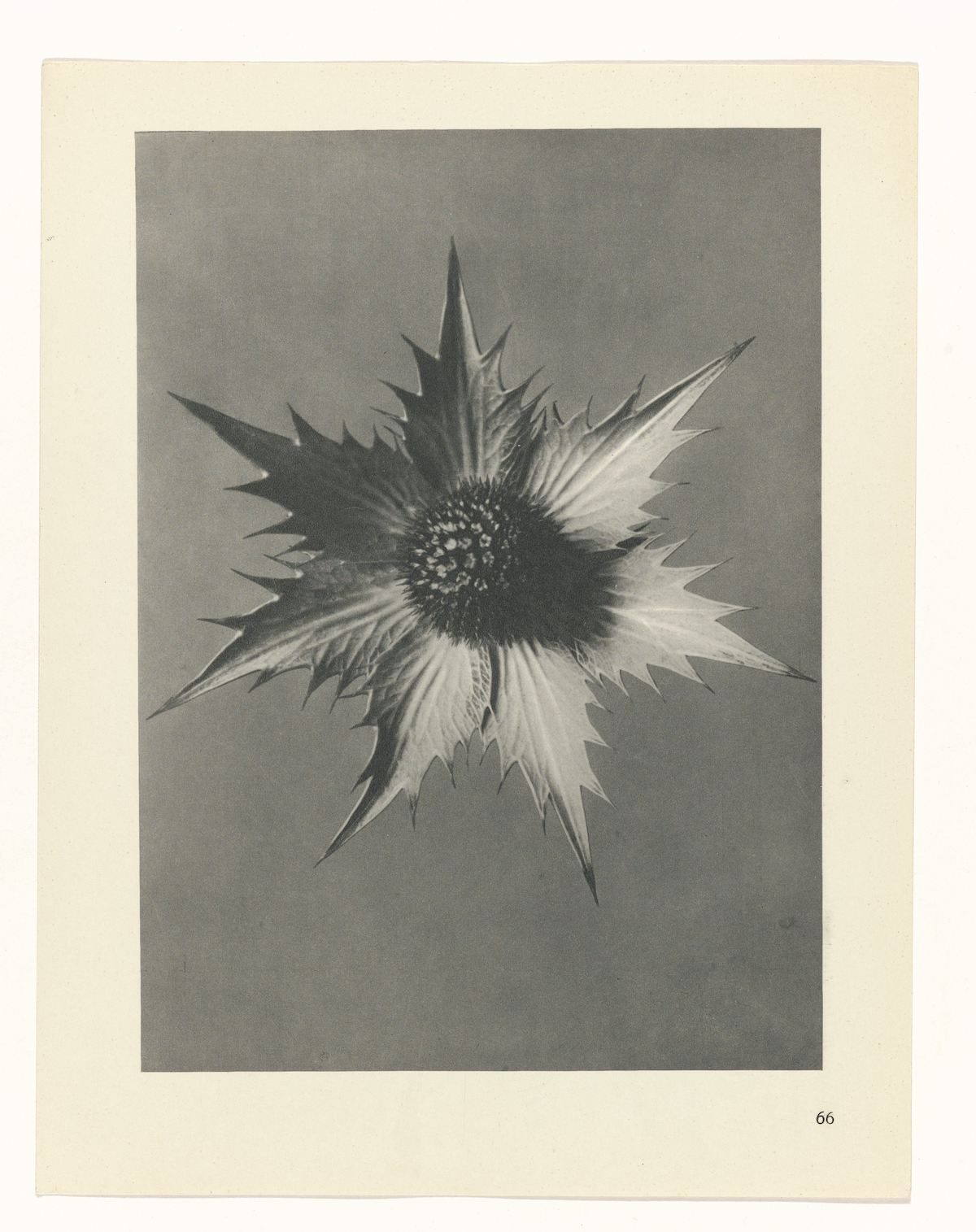

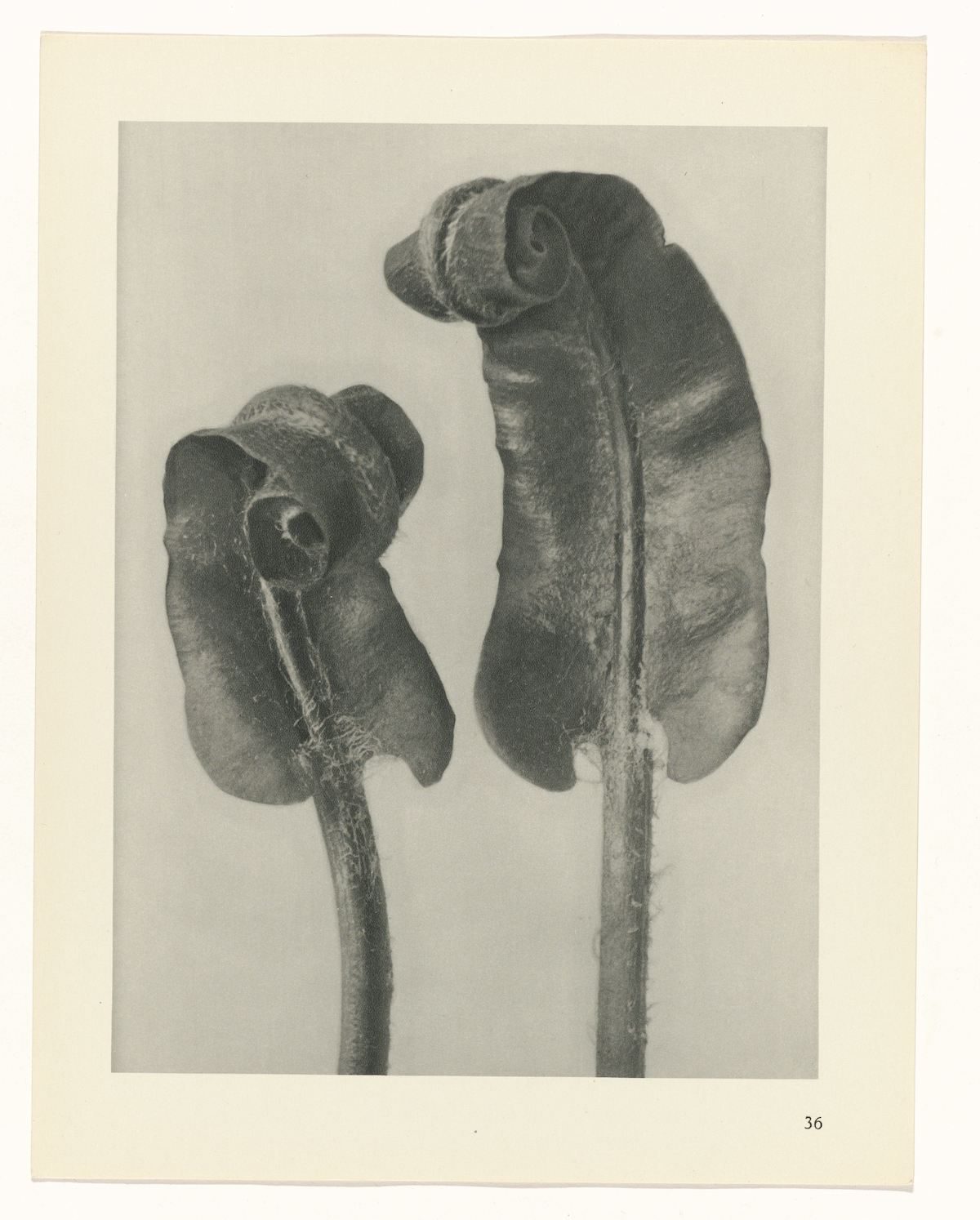

Karl Blossfeldt (June 13, 1865 – December 9, 1932) was a German photographer, sculptor, teacher and artist. Working in Berlin, he is best known for his detailed photographs of plants and living things, published as a collection in 1928 as Urformen der Kunst (Art Forms in Nature) – a title his fellow countryman Ernst Haeckel had used for his sensational work on tiny living things in 1904. Both men showed us a hitherto “unknown universe”.

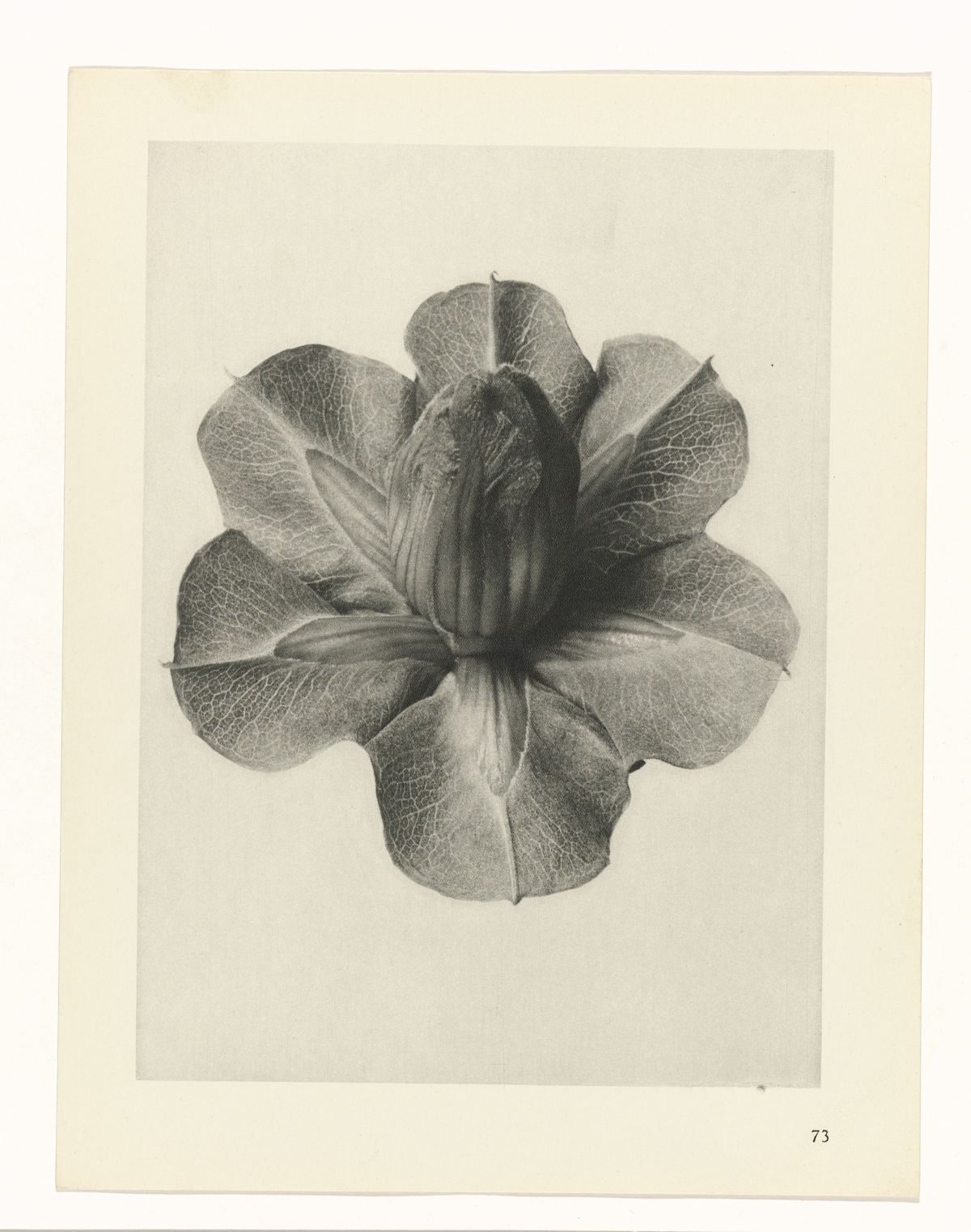

Blossfeldt’s factual yet finely detailed imagery was praised by German philosopher, cultural critic and essayist Walter Benjamin (15 July 1892 – 26 September 1940), who declared that Karl Blossfeldt “has played his part in that great examination of the inventory of perception, which will have an unforeseeable effect on our conception of the world.”

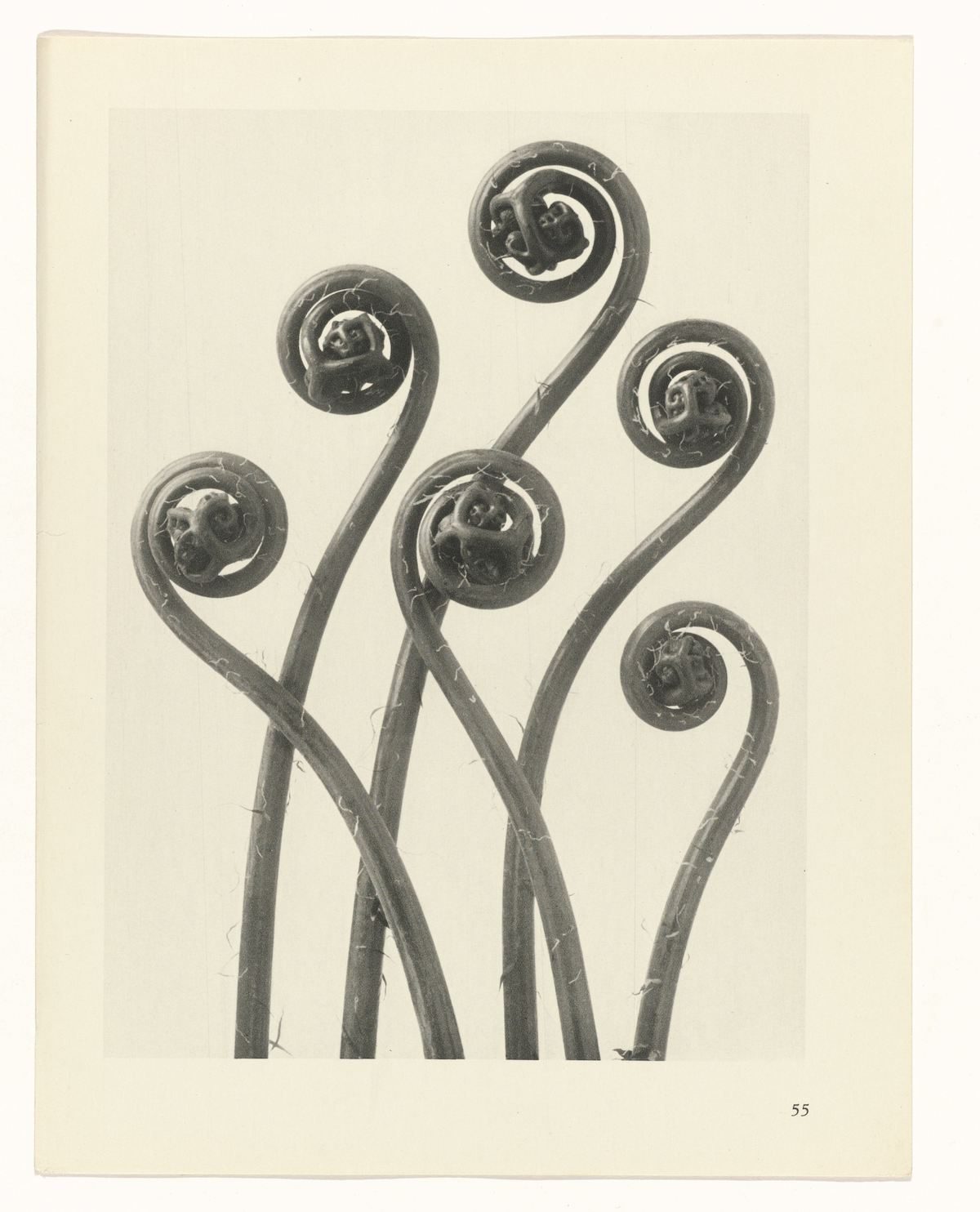

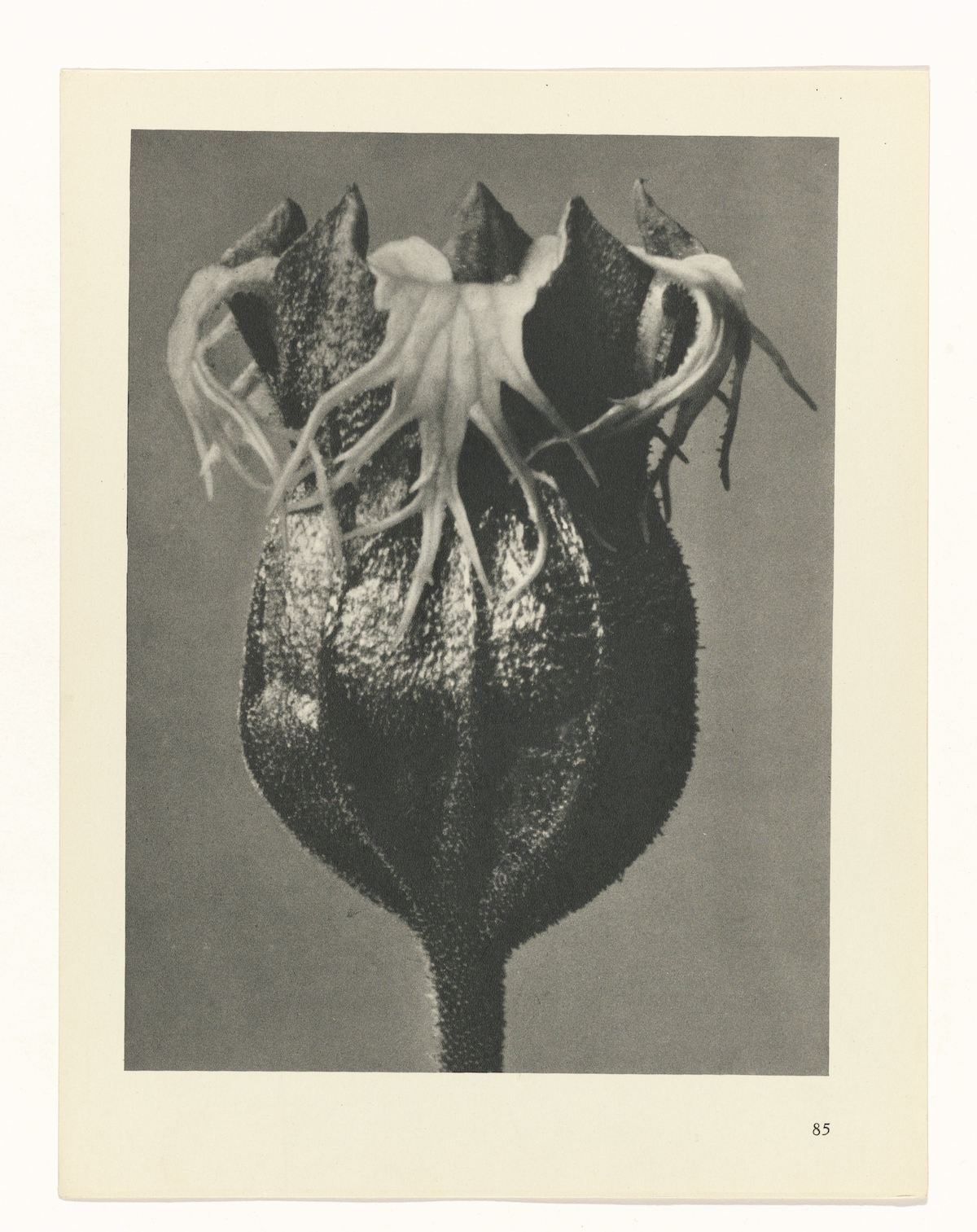

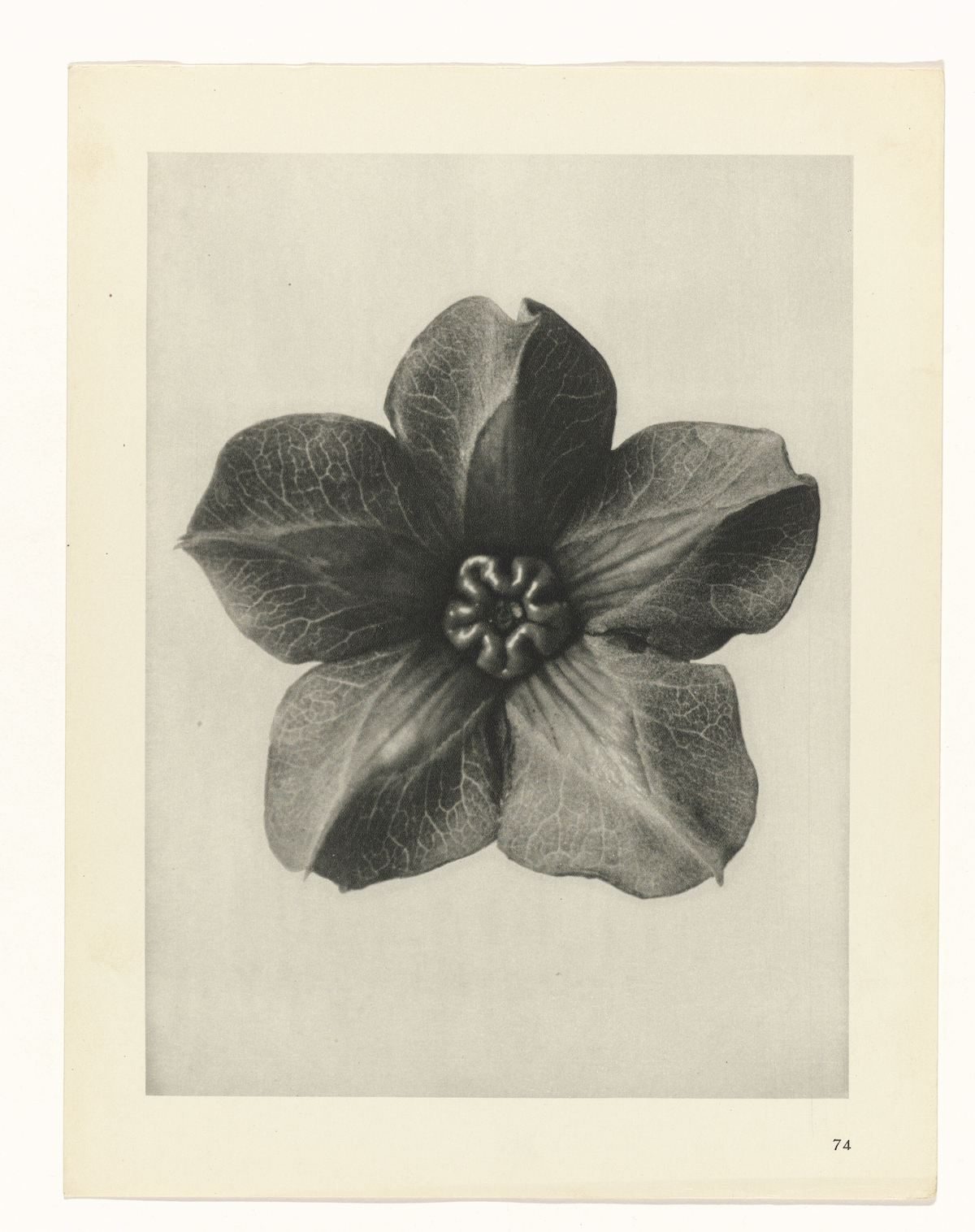

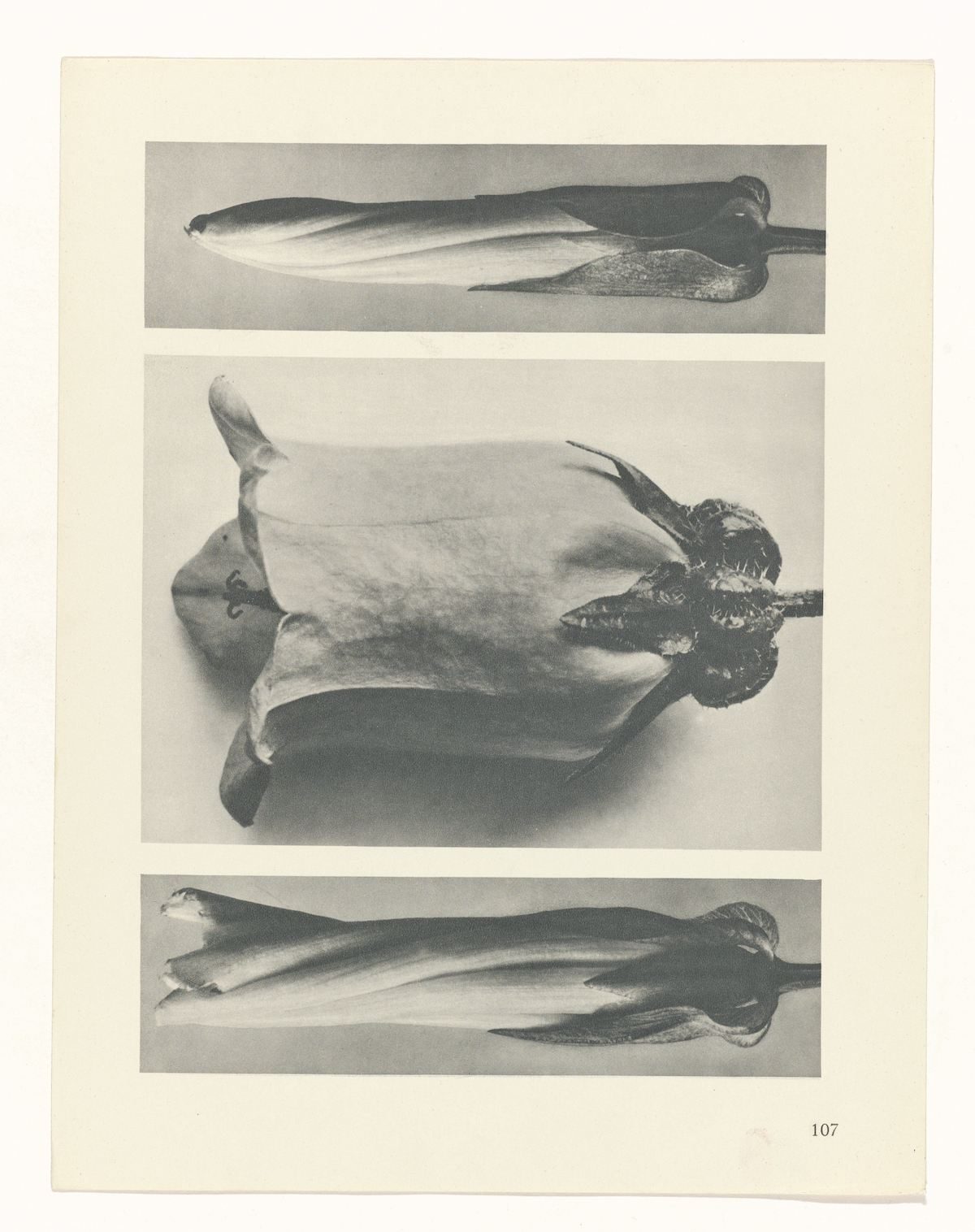

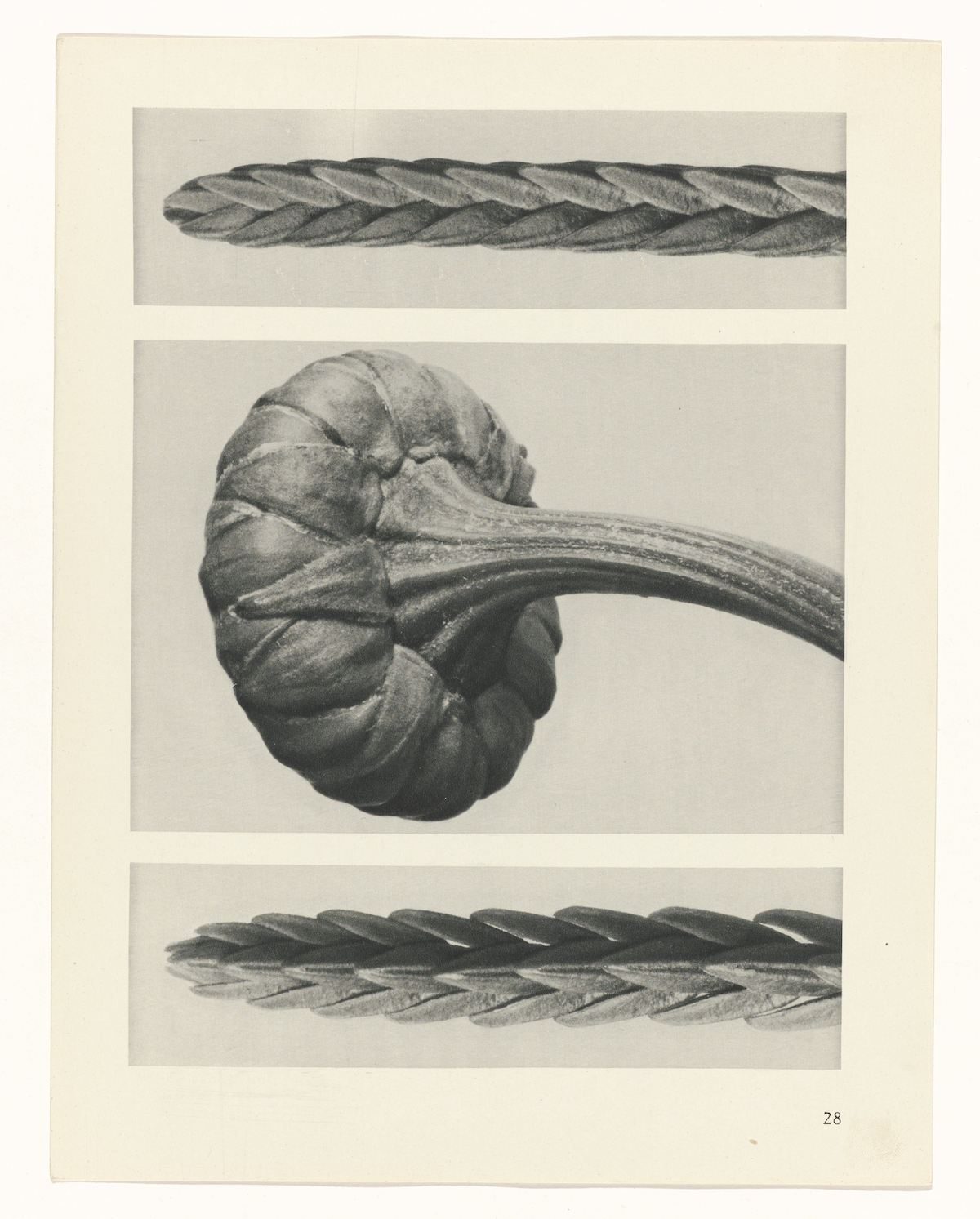

As with Johan Wilhelm Weimar’s Wonderful Herbarium and Imogen Cunningham’s Sublime Close-Up Botanical Photos from the 1920s and 30s, Blossfeldt believed that “the plant must be valued as a totally artistic and architectural structure.”

A largely self-taught photographer, Blossfeldt made many of his photographs with a home-made camera that could magnify the subject up to 30 times its size, revealing details within a plant’s natural structure.

The book, published when Blossfeldt was professor of applied art at the Berliner Kunsthochschule (Berlin Academy of Art), became an international bestseller. Regarded as a seminal book on photography, Blossfeldt’s influence was likened to Maholy-Nagy and the pioneers of New Objectivity, his achievements ranking alongside photographers August Sander and Eugene Atget.

The Surrealists also championed him, and George Bataille was fascinated by the “hallucinatory clarity and sinister sexuality” of Blossfeldt’s plant forms and used several of the photographs to illustrate his essay on the enigmatic “language of flowers” in the first issue of his review Documents in June 1929.

“My botanical documents should contribute to restoring the link with nature. They should reawaken a sense of nature, point to its teeming richness of form, and prompt the viewer to observe for himself the surrounding plant world.” “The plant never lapses into mere arid functionalism; it fashions and shapes according to logic and suitability, and with its primeval force compels everything to attain the highest artistic form.”

– Karl Blossfeldt

Blossfeldt shares this bridging of two centuries with other great collectors in the history of photography, such as the Parisian Eugene Atget, and it is to this bridging of two centuries that his influence may be attributed today … The plant photographs were produced by simple means. Legend has it that a relatively straight-forward homemade camera was used, one common in its time and not very large, with a format of 9 X 12 cm.

The glass plates which served as negatives were coated with inexpensive but not completely neutral-coloured orthochromatic emulsion, and occasionally – after 1902, as they became more widely available – with panchromatic emulsions, making possible a neutral reproduction of the colour red in halftones. Since the first emulsion was thin and therefore enabled high contrast with extremely sharp edges, it served especially to stress the structural elements. It was thus used primarily for photographs with white or grey backgrounds. The rarer photos with panchromatic emulsions were used to illustrate entire clusters or beds of flowers with a wider variation of chromatic values or halftones.”

– Rolf Sachse from the book Karl Blossfeldt Benedikt Taschen Verlag (April 1997)

A letter written by Blossfeldt to the director of the Königliche Kunstgewerbemuseum in April 1906 is telling

in many regards, writes Hanako Murata:

I hereby respectfully submit to the director a collection of enlargements of plants. Some of the main subject teachers to whom these photographs have recently been shown have been positive in their comments and consider them suitable for lessons..

In many cases, these photographs were made by enlarging small details that students could not easily make out in

evening light…I probably have more than a thousand of such photographs, from which, however I can only slowly make prints. Because they are the fruit of years of work and considerable material sacrifice, I would very much welcome their being used in some way, either as inspirational material in individual classes, libraries, etc. for a wider audience and, above all, for all students…

The sculptor… can only make profitable use of the smaller, simpler plants that grow wild. There plants are a treasure trove of forms — one which is carelessly overlooked only because the scale of shapes fails to catch the eye and sometimes this makes the forms hard to identify. But that is precisely what these photographs are intended to do — to portray diminutive forms on a convenient scale and encourage students to pay them more attention. .. To facilitate discussion of these photographs, I feel it would be advisable to affix these prints in advance to a wall.

I will gladly be of service here. There are 210 sheets measuring 20 × 30 cm each, and they would require an area of around 12 square meters.

The plant never lapses into mere arid functionalism; it fashions and shapes according to logic and suitability, and with its primeval force compels everything to attain the highest artistic form.

– Karl Blossfeldt

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.