“My dear Lydia Lova – You will not remember me but I remember you so well. We were at Ravensbrück together. I just want to say how very happy I am for you that the French Government have recognized all the good you have done for France and for all of us. I read yesterday that you were given the Légion d’Honneur by General Masson. We who remember are very proud of you. Good luck to you, our little heroine, always and all my love”

— Rosa Stern (No. 39486): Kiel.

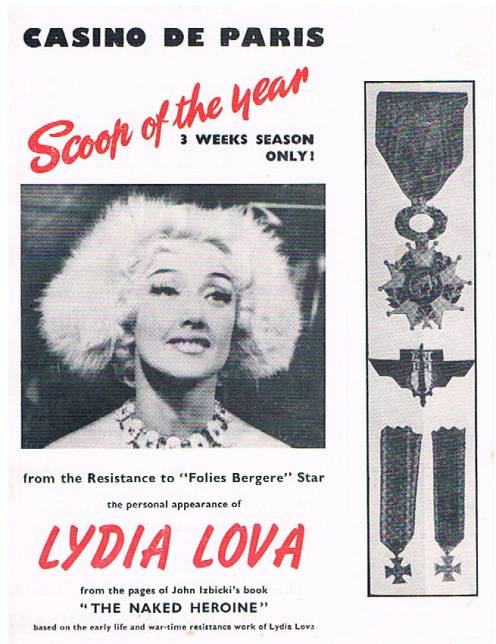

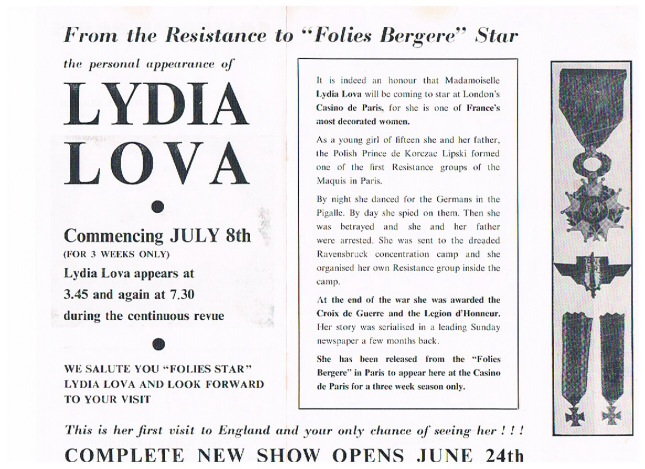

On July 3, 1963, Lydia Lova arrived in London to perform at Soho’s Casino de Paris Striptease Theatre. Booked into the Mayfair Hotel, Lydia was “The Naked Heroine”, the alluring Polish dancer (née Lydia de Korczak Lipski on January 8, 1925) who fought the Nazis as a 2nd Lieutenant in the Fighting French Forces Unit Resistance Deportee (unit of foreign born resistance fighters), survived torture at the hands of the SS in Ravensbruck concentration camp and become a showgirl at the hymned Paris nightspot, the Folies-Bergère. In 1960 she was awarded the Croix de Guerre and the Légion d Honneur.

Lydia’s is a remarkable story. How did the daughter of Irenka de Korczac Lipski and Poland’s Prince Wladimir de Korczak Lipski, a direct descendant of Prince de Korczak, King of Hungary in 1120, end up stripping in Paris and London?

In his book The Naked Heroine, John Izbicki explains how a small notice in the French Press on a young woman being awarded a medal for courage intrigued him:

Who, I thought, was this woman and what had she done to help the Resistance movement while France was under Nazi occupation? I searched through the other French papers on my desk and found the same brief announcement in the pages of France Soir and Paris Presse.

I decided to investigate further and discovered from the Journal Officiel that Mlle de Korczac Lipski had already been decorated with the Croix de Guerre with Palm and numerous other medals, including the Croix de Combattant Volontaire Résistant and the Médaille Réconnaissance de la France Libre. Lydia de Korczac Lipski, it transpired, was the most decorated woman in France. I was growing increasingly interested in her. Who was she? What did she do in the Resistance? And what was she doing now? I had to find out…

I desperately needed a break and it came soon enough when the telephone in my office began to ring. My Journal Officiel contact had phoned me back to tell me that Mlle Lipski was better known as Lydia Lova and she was the top-billing nude dancer of the Folies-Bergère. Within one delicious minute, an interesting little story had turned into a sensational scoop.

Would she be keen to tell her story? No. She told the writer: “If you want to write about my dancing at the theatre, then please go ahead. I have no objections. But please forget the other matter. It is in the past and I’d rather forget it.”

How could she forget her past? Lydia Lova was no self-regarding diva. Far from it.

Her reluctance to speak freely to me or any other journalist was that she refused to have the name Lydia Lova connected in any way with her real name – Lydia de Korczac Lipski, daughter of a Polish prince. The very idea that people might think she was drawing on her background for cheap publicity was totally abhorrent to her.

Ten-year-old Patrick, son of Lydia Lova, watches the ceremony where his mother is receiving a Legion of Honor for her activity during the German occupation as a member of the French Resistance, Paris, France

Dancer Lydia Lova, former member of the French Resistance, receives her Legion of Honor from General Henri Masson during a ceremony held at the Invalides, Paris, France

Soon after she talked., Izbicki had material for four features in Britain’s The Sunday Graphic. After some negotiation, Lydia agreed for Izbicki to write her life story. In an apartment on Paris’s Left Bank she talked and talked. Ibicki was profoundly affected by what he heard. Anyone sane should be.

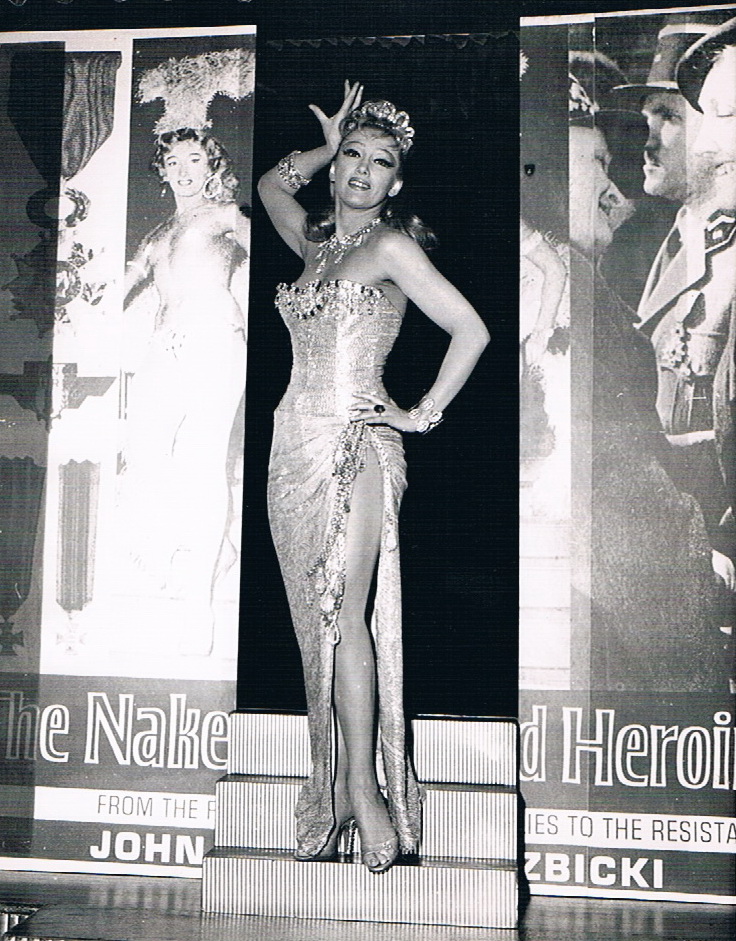

One of Lydia’s most famous dances showed her in a pas-de-deux with the devil, a physically magnificent young male and almost nude dancer, both of them cavorting across a blood-red stage with real-looking flames licking the edges of a deep pit in the centre of the stage hell. The devil plays a haunting melody upon a glass violin, whose tune is taken up by the orchestra in the theatre’s own and very real pit. Lydia, a beautiful fallen angel, pirouettes around the stage, enticing the devil who, of course, falls madly in love with her. He lures her ever closer to him and closer also to the fiery pit and, as they dance together, the flames leap ever higher until these two hellish lovers are engulfed by the flames and disappear into the pit.

This particular ballet always proved one of the most popular with audiences at the Folies-Bergére. But to Lydia, who never failed to make her exit into the wings and back to her dressing room with the tears streaming from her eyes, that ballet brought back her most dreadful memories. It symbolised her past, her childhood. It conjured back the nightmares of Fresnes Prison and Ravensbrück Camp where she had been confronted by the devil incarnate and almost engulfed in the flames of the crematorium. And when Lydia used to return to her apartment in the rue HegesippeMoreau, high over the rooftops of Montmartre in Paris, she used to drink a large glass of milk and go to bed with a prayer that this time perhaps, she

would not be visited by those dreadful dreams of death. But they did come. They almost always did.No medal, however golden, could have ever have wiped clean the past for Lydia or manage to interpret fully the true heroism of that naked dancer of the Folies-Bergére.

Eric Lindsay, owner of the Casino de Paris, wanted Lydia to dance at his club in London’s Soho. She agreed.

Eric tells us :

The Press descended on the Mayfair Hotel for a reception. Brian O’Hanlon, who was our PR at the time, pulled all the stops out. She was in every single paper in England and her story was syndicated throughout the world. Lydia was ecstatic about the results, and so were we. Rehearsals began on the 5th of July and went really smoothly. Up until her opening day and between rehearsals she was being interviewed all the time by various member of the press.

Her story was so intriguing. This young girl had been in the French Resistance during the War and had been captured and sent to Ravensbruck Concentration Camp. She had finished up in the experimental wing of the camp, where they tried out all manners of vile tortures. She was injected in November 1944 by Dr.Hans Gerhart, one of the camp’s butcher doctors. When she asked what it was for, she was told not to worry, and that she would find out in about 20 to 25 years. This was the inhuman way the Germans treated their prisoners. The miracle was how, through all that she had endured, there emerged this glamorous and charming lady who wowed the Press with her Parisian style and elegance.

Lydia’s act was a smash hit. We staged it so that she appeared onstage between the covers of her book, “The Naked Heroine.” She sang, danced and finally stripped with such elegance that even the most prudish would have found her performance enchanting.

The three weeks just flew by, but during that time we had become firm friends and she left with the promise that whenever she wanted to come to London she would come and stay with Ray and myself at Marston Close. The house was quite large and she would be a welcome visitor.

One Sunday later that year when she was staying with us, Lydia and I were lounging around the house. Ray had gone off in the car with his mother to see her mother and sisters so that she could boast to them as to how well her son was doing.

We had a manservant at the time called Carl Coffee who was a wonderful cook and a very amiable person. I couldn’t understand why he was not around pottering in the kitchen. I said to Lydia, ‘I suppose he’s been out on the tiles and stayed with friends. He’ll most probably be back soon.’ So I thought nothing more about it and we had our breakfast. A little later the doorbell went and there on the steps were two uniformed policemen. The first thing I thought was that there must have been an accident. ‘Does Mr. Carl Coffee live here?” asked one of the officers. ‘Well, yes,” I asked. ‘Why?’ ‘I’m sorry to inform you that he is dead,’ he replied. ‘As you were the last person to see him alive, you must come and identify him.’ I nearly shat myself.

Apparently Carl was in a cinema in Edgware Road for the last performance. When they played ‘God Save the Queen’ and the audience stood up, Carl was the only one sitting! I began to think quickly. I had never seen a dead person. I really had no desire to see a corpse. I thought that maybe I could palm the task off on Ray when he got back. I told the policeman that I had no transport, but he informed me they could take me in the police car. I didn’t like the idea of that. It was bad enough that the neighbours knew that Ray and I owned a strip club. God alone knows what they would think if they saw me being dragged off in a police car. After I explained that I couldn’t leave the house until later that afternoon the policemen agreed to come back at 3p.m. I breathed a sigh of relief and shut the door.

I turned to see Lydia, who had heard the conversation, standing there ashen and shaking. I said to her, ’Why are you shaking? You must have seen loads of dead people in Ravensbruck.’ When I added, ‘ As a matter of fact, you know what Carl looked like, you can go and identify him!’ She nearly fainted. I was trying to palm it off onto anyone. To cut a long story short, it was decided that I would go, if Ray hadn’t returned in time. Of course, he didn’t, but I made Lydia promise that she would come with me and stay outside whilst I was in the mortuary.

The police car came back right at 3p.m. When Lydia and I got into the car, a few of the neighbours were hanging out their windows. Oh the shame! Lydia and I sat in the car not uttering a word. It was all a bit of a haze thanks to the half a bottle of whisky we had got through while we were waiting. All I remember of the mortuary was that it was freezing cold. There on a slab was poor Carl. My eyes really focused on the label that was hanging from his toe. After I had identified Carl’s body, the police thanked me and buggered off, leaving Lydia and I to find our own way back to Swiss Cottage. So much for helping the police out!

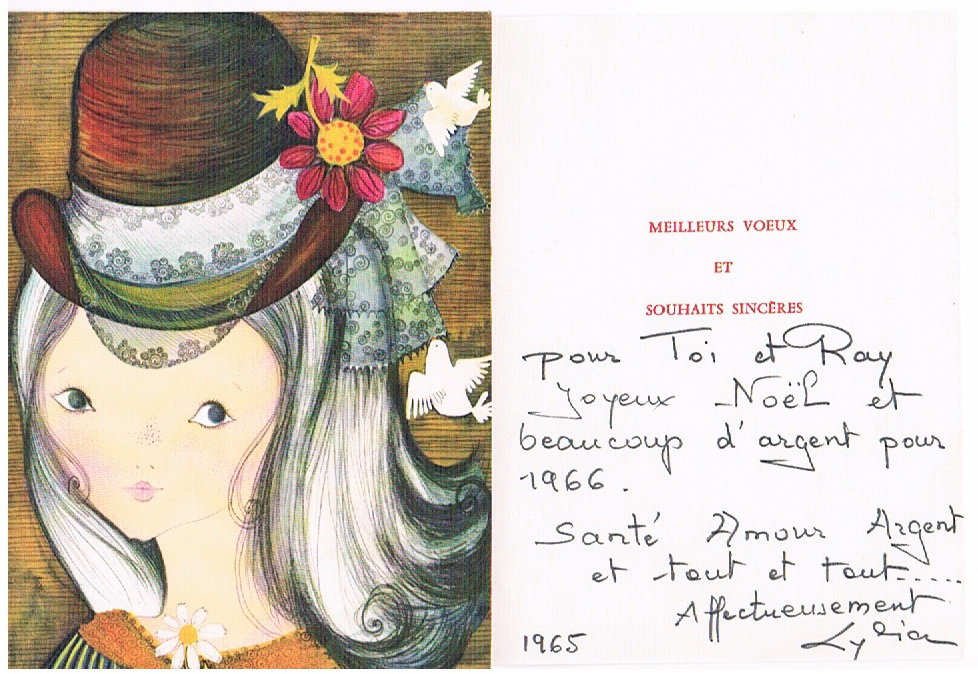

Ray and I would see Lydia whenever we were in Paris which was very frequently and she also spent Xmas and New Year with us in London in 1964.

A favourite restaurant of ours in Paris was Au Mouton de Panurge, which was an old monastery, were the waiters dressed as monks. One of their specialties was a garter that they fitted on all the ladies. It was all great fun and the food was excellent.

The last note I received from Lydia was at Xmas in 1965.

FOOTNOTE

At the conclusion of the “The Naked Heroine,” John Izbicki wrote, “The effects of the injection which she was given in Ravensbruck have yet to make themselves felt. What they will be, no one can guess. Doctors have examined Lydia thoroughly but they have been unable to make any conclusive diagnosis. But until then, Lydia Lova will go on dancing and praying and living with her memories-the memories of a Naked Heroine.”

Lydia Lova died on the 3rd of February, 1966, 22 years after being injected.

War And Why

Lydia’s father Wladimir fought with the British Army as a volunteer during World War 1. It was a country he admired greatly. From 1919 until 1922 he was employed by the British Secret Service under General Carton de Wiart, then chief of the British Military Mission in Warsaw. To progress through the ranks, Wladmir took a job in Warsaw and became a full British citizen. But the mood had darkened. Many despised the aristocrats. When Lydia was seven the family moved to France, first to Nice and then to Paris. Things we fine. The Lipskis had another child, Gerald. But in 1939 someone evil was in the air. Mrs Lipski thought it safer to take herself and Gerald to Poland. Not all of them could afford to make the trip. Lydia was 13. She never saw her brother nor mother again.

Nigel Perrin has more on his excellent site. He tells us how Lydia became a freedom fighter.

Interallié was the creation of a determined Polish staff officer, Roman Czerniawski, who chose to stay behind in Paris after the fall of France. He built up a formidable intelligence organisation across Occupied France and became an invaluable source for MI6, but in November 1941 he and more than fifty of his agents were arrested by the Abwehr. Some agreed to collaborate, but Czerniawski held his nerve and cleverly conned his interrogators into sending him to London as a double agent. There was one condition to his freedom, however: as insurance against any further treachery, Czerniawski’s agents would be held as hostages. If he cooperated, his comrades would be safe. If he decided to change sides again or renege on the deal in any way, they would suffer the consequences.

But once in England Czerniawski did turn again, and as MI5’s agent “Brutus” he became one of the heroes of its double-cross system and a crucial player in the success of the D-Day deception strategy. His MI5 case officers did a tremendous job in fooling Czerniawski’s handlers, and to the end the German High Command’s faith in Brutus’s reports remained unshakeable. But what happened to those he had left behind in France? In his recent book Double Cross: The True Story of the D-Day Spies, Ben Macintyre states that “When Paris was liberated, so were the hostages”. Unfortunately the truth is much darker.

The Abwehr did not keep its promise. Beginning in March 1943, a total of forty of Czerniawski’s agents were packed aboard trucks and deported to concentration camps in Germany; classed as “Nacht und Nebel” (Night and Fog) prisoners – political opponents of the Nazis – they could expect the most brutal treatment and were unlikely ever to see France again. Among them were two Polish émigrés, Wladimir de Korczak Lipski and his teenage daughter Lydia, both of whom Czerniawski had personally recruited. For nearly a year they had worked together as a team, collecting details of troop movements, noting the positions of anti-aircraft batteries, running errands, quietly doing whatever was asked of them. Lydia’s passion was for dancing but she also discovered a talent for technical drawing and often copied blueprints of factories and German military installations for Interallié’s regular courier to London; the network codenamed her Cipinka.

On 18 November 1941, Czerniawski was arrested with his mistress, and the collapse of Interallié soon followed. Within hours his deputy, the extraordinary Mathilde Carré, began giving up nearly everyone she knew, and four days later she led the German secret police to the de Lipski’s Montmartre apartment. Not yet seventeen, Lydia would spend the next eighteen months in miserable conditions in La Santé and Fresnes prisons, sometimes in solitary confinement. Smuggling in notes to her, Wladimir tried to keep up her spirits; in one he wrote, “Do not forget that you have great talents, and that one day you can have a beautiful and happy life”. They were reunited briefly at the fortress at Romainville on the outskirts of Paris, but in July 1943 Lydia was deported to Ravensbrück concentration camp. There she spent several months in the punishment block, which regularly supplied human guinea-pigs for medical experiments. She later recounted how she had received a mysterious injection from a doctor (possibly the prominent SS surgeon Karl Gebhardt, who was later tried at Nuremberg and hanged) who told her that its effects would not appear for at least twenty-five years.

In April 1945 she was saved when a Red Cross transport evacuated her to Denmark (a later one also saved SOE agent Yvonne Baseden) and Wladimir, having himself endured two years in Mauthausen, was reunited with his daughter at a convalescent home in Switzerland. Remarkably, only seven of the forty Interallié agents deported did not return: Wladimir’s friend and fellow agent Lucien de Rocquigny had been beaten to death in Mauthausen’s dreadful quarry, while others had lived to see liberation only to succumb to typhus before they could be repatriated.

Still only twenty-one, Lydia slowly began to live again. She regained her health, gave birth to a son, and returned to her first love, dancing. By 1950 she was appearing at the Folies Bergères as “Lydia Lova”.

Lydia Lova (January 8, 1925 – February 3, 1966). Never forget.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.