A few years back I came across Malcolm McLaren’s annotated copy of Indian Rawhide, the anthropologist Mable Morrow’s study of the folk art produced by Native American tribes which inspired the late cultural iconoclast in the conceptualising with his partner Vivienne Westwood of their Spring/Summer 1982 fashion collection Savage.

Frontispiece to Morrow’s book, published by University of Oklahoma Press in the Civilization Of The American Indian Series, 1975

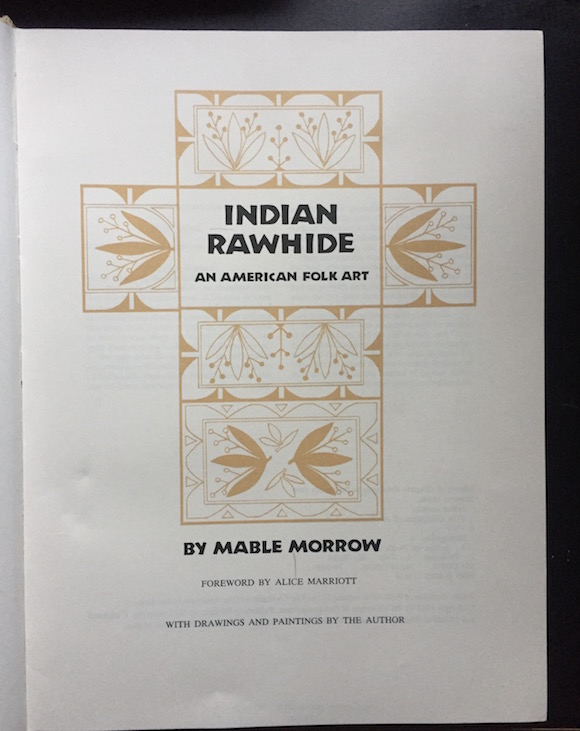

From Indian Rawhide: design produced by the Apache Mescaleros in Taos, New Mexico, matched by McLaren and Westwood with book-end marbling on this Savage slip dress. No reproduction without permission/

The Apache design as it appeared printed on the end of the train on a Worlds End jersey toga dress. No reproduction without permission

McLaren obtained a copy of Morrow’s book during travels recording his debut solo album Duck Rock. Since the Pirate collection of March 1981 had established a post-Punk direction for himself and Westwood and their Worlds End shop and label, McLaren set about investigating the powerful ideas residing in pre-Christian ethnic cultures, selecting Indian Rawhide as the text with which to frame the next group of designs.

My McLaren biography, to be published in spring 2018, will reveal that research – particularly literary – was one of the life-long consistencies in his approach to creative acts.

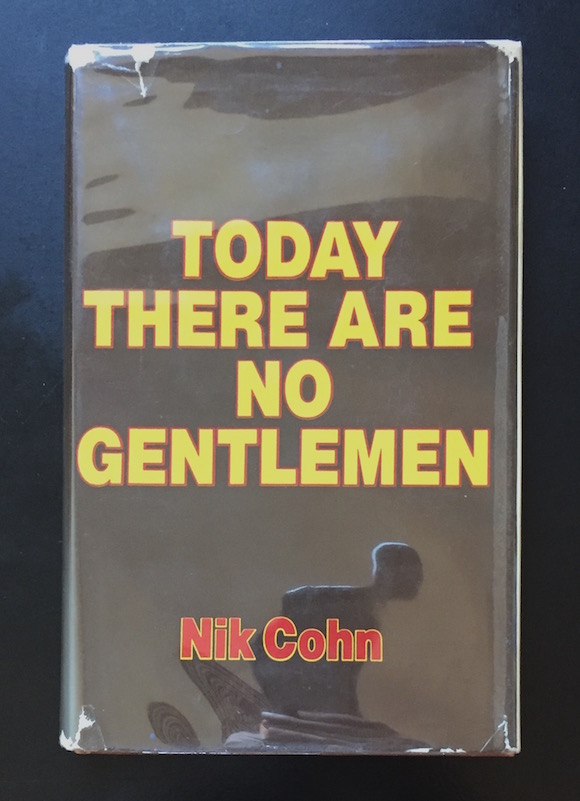

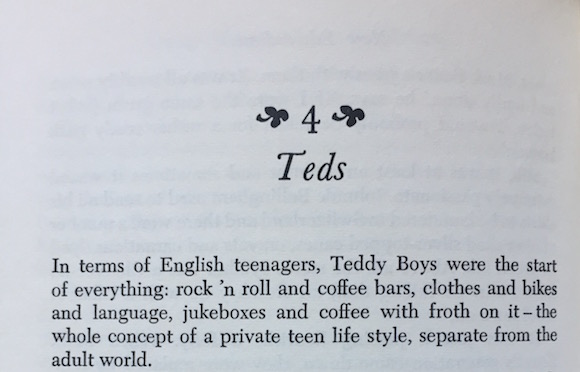

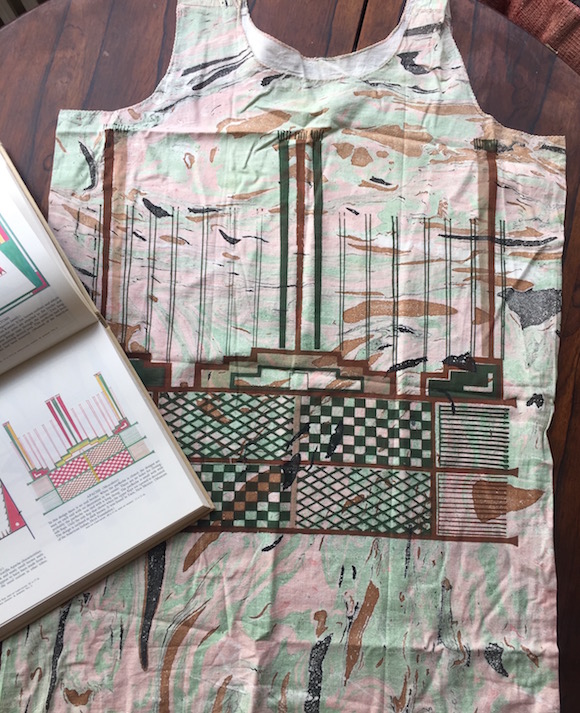

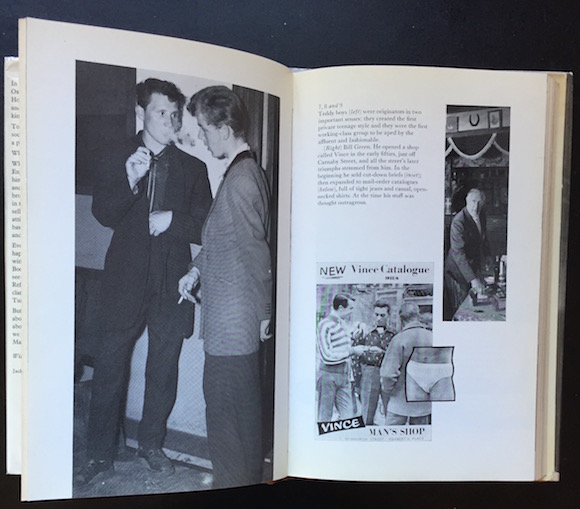

The musician Robin Scott told me that McLaren was an avid attendee of art history lessons during their spell as students at Croydon Art School in the 60s, and a couple of years before his death in 2010 McLaren confirmed that he was inspired in part to open Teddy Boy revival emporium Let It Rock at 430 King’s Road in 1971 after reading Nik Cohn’s peerless post-WW2 youth cult history Today There Are No Gentlemen.

Book illustrations link the youth cult to such outlets as Bill Green’s Vince Man Shop, which opened in central London in 1954 and was a favourite of McLaren’s

Indeed, this was recognised in one of the first media pieces on the boutique at 430 Kings Road when Rolling Stone described McLaren as “like a real historian”. Asked why he lavished care and attention upon what was considered trivial, McLaren responded: “Somebody’s got to keep track of these things.”

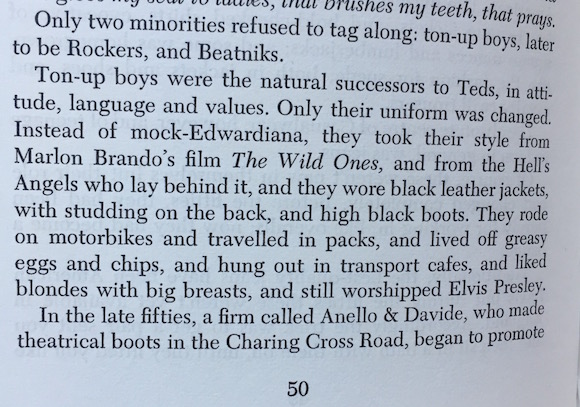

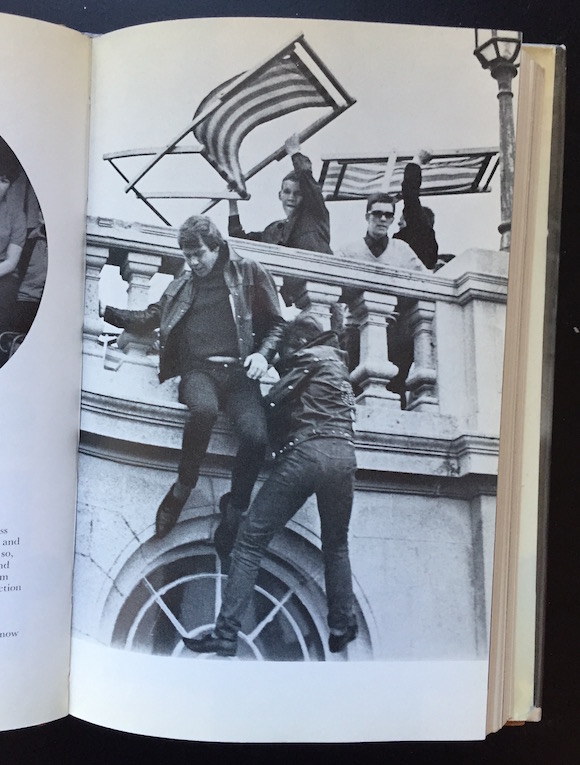

From the section in Cohn’s book on Rockers, the inspiration for McLaren to change 430 King’s Road from Let It Rock to Too Fast To Live Too Young To Die in 1973

Stylishly clad Rockers escape marauding Mods in this 1964 illustration from Today There Are No Gentlemen

Cohn’s delineation of the criminal subtext of the zoot suit appealed to McLaren’s interest in outsiders; as Too Fast To Live Too Young To Die, 430 King’s Road also stocked “Alan Ladd” and “Jazz” zoot suits, two-tone shoes, spearpoint and tab-collared shirts and satin ties

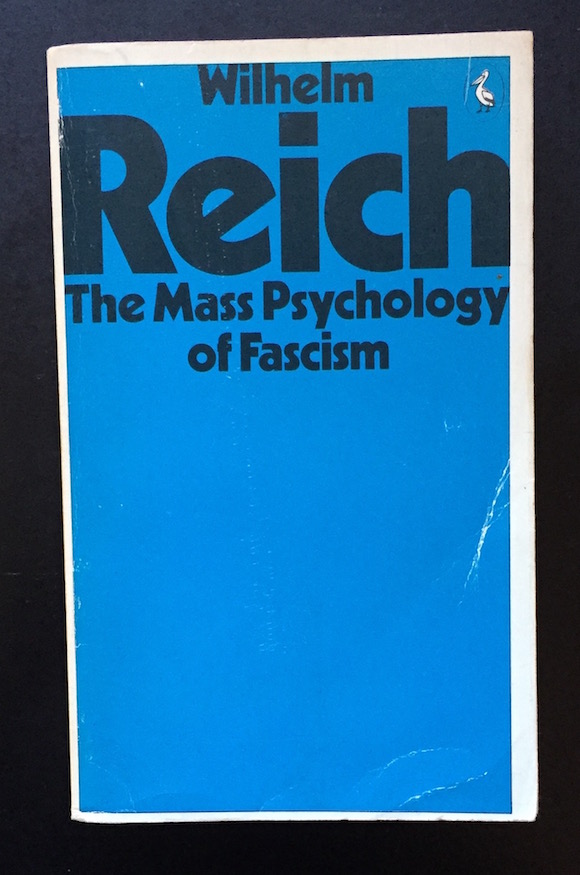

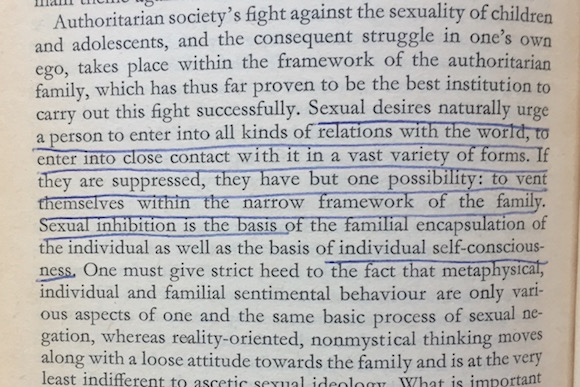

Nik Cohn’s examination of not just rockers but also zoot suits proved useful when McLaren changed Let It Rock to Too Fast To Live Too Young To Die, while Wilhelm Reich’s theories about sexual repression – specifically as expressed in McLaren’s favourite work by the German psychoanalyst, the 1933 book The Mass Psychology Of Fascism – informed the atmosphere in which the boutique was operated as Sex.

Reich’s thoughts on the exploration of sexual desires as a means of resistance informed Sex at 430 King’s Road

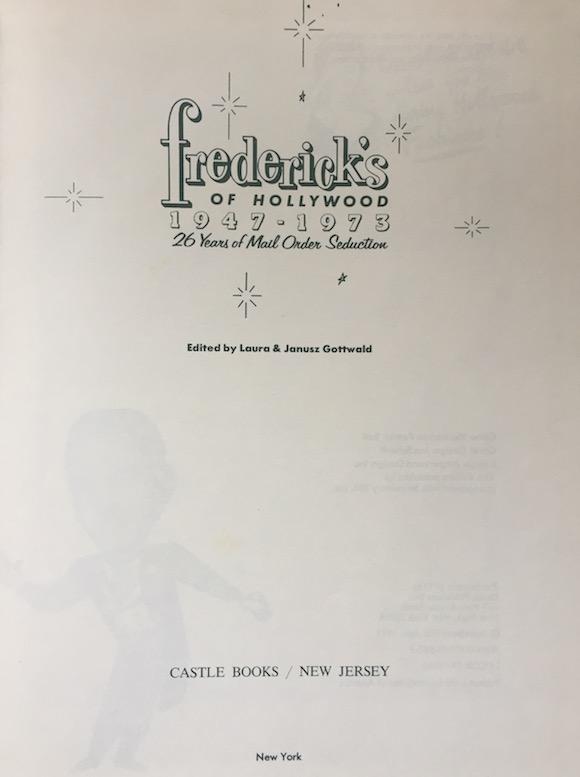

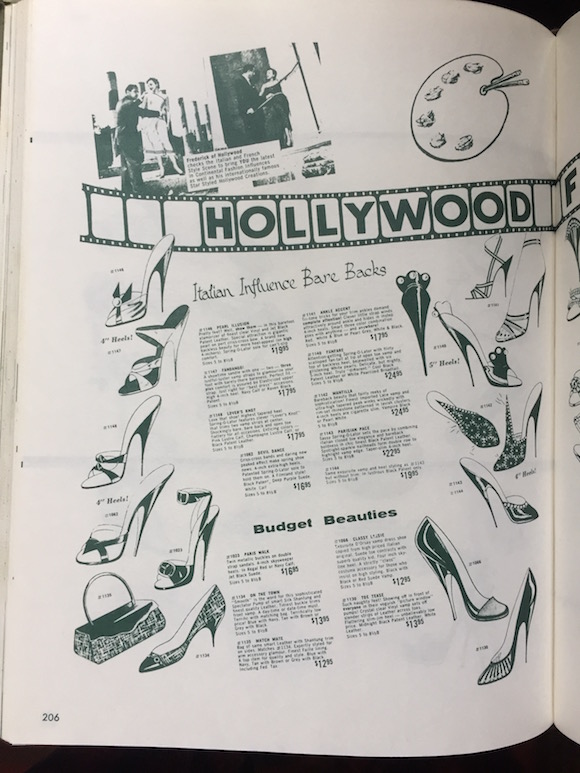

Around this time McLaren and Westwood visited the expat American artist/writer Judy Nylon at her north London flat; she loaned them a book published to celebrate the quarter century-plus existence of Los Angeles glamour-wear outlet Frederick’s Of Hollywood. Nylon was to never see her copy again, though a few of the catalogue’s design ideas made it in the mix for sale in Sex.

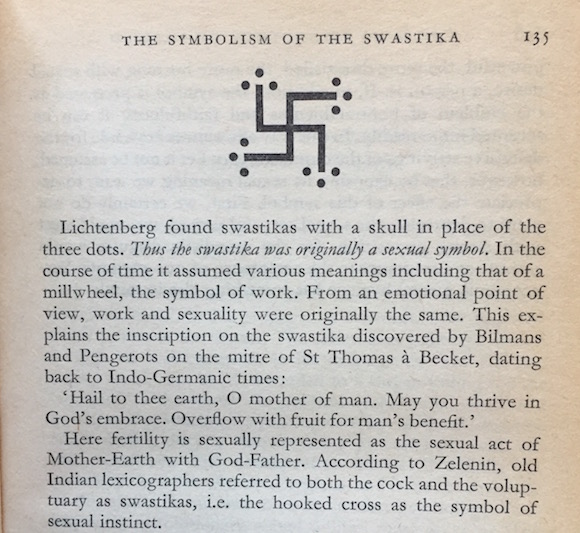

And when 430 King’s Road was changed again, to Seditionaries in 1976, Reich’s thoughts on the swastika’s original sexual potency in his book were contemplated by McLaren as he created the notorious Destroy top worn by the Sex Pistols.

The potency of the swastika was dangerously explored by McLaren in such designs as Destroy, realised with Westwood in the Spring 1977 Seditionaries collection

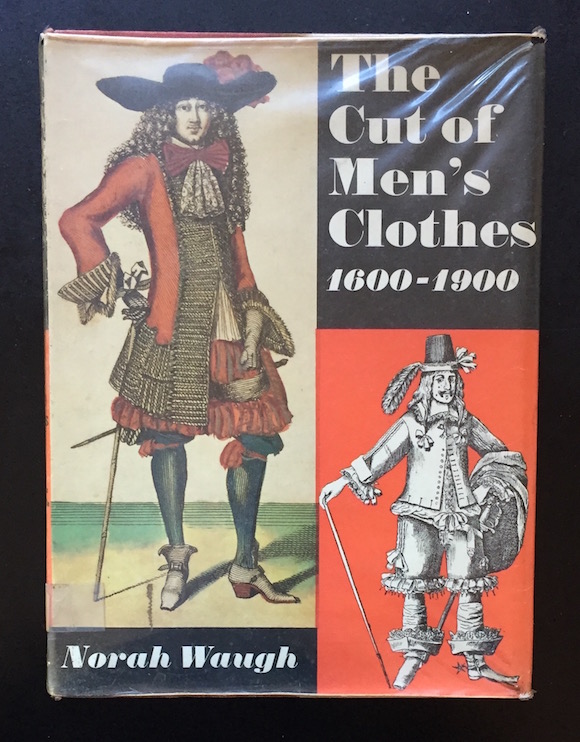

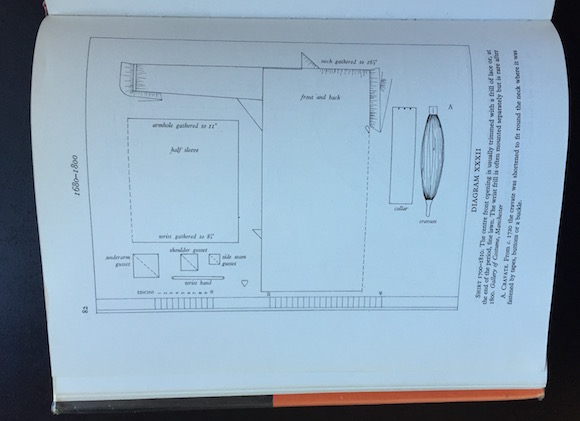

By the time Seditionaries hit the skids in the late 70s, Westwood – no slouch at historical research herself – was working on applying centuries-old techniques to contemporary fashion by absorbing the designs in Norah Waugh’s The Cut Of Men’s Clothes 1600-1900.

The open-fronted version of this 18th century chemise design without neck or wrist frills became the loose-fitting garment selected by McLaren from suggestions by Westwood as the basis for the Worlds End Pirate collection of 1981

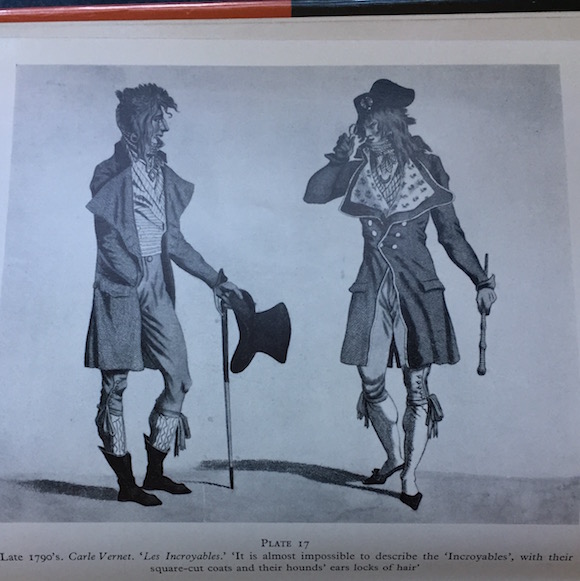

Norah Waugh’s mentions of the French Revolutionary dandies Les Incroyables prompted research which came to fruition with the S/S 1983 McLaren/Westwood collection Punkature

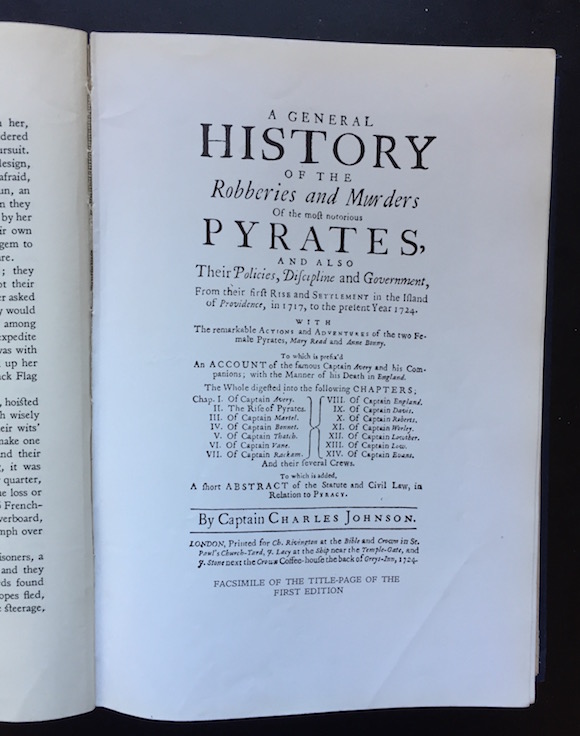

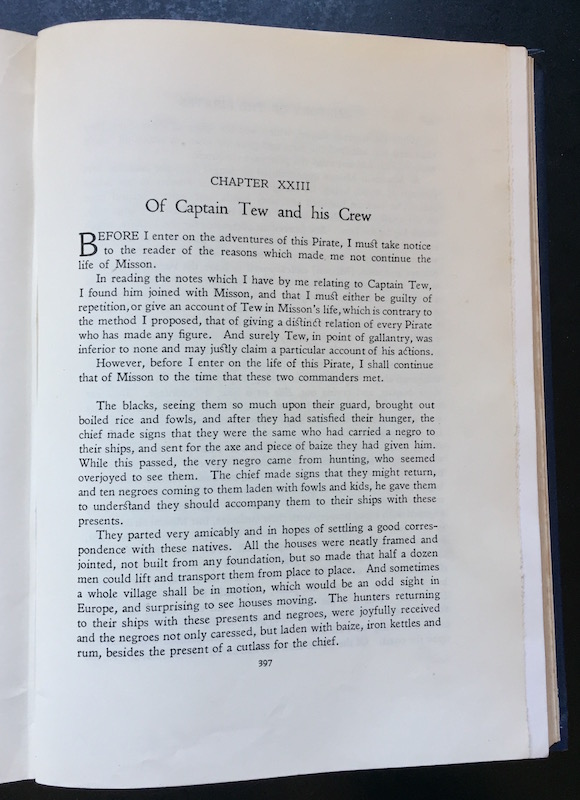

Another springboard for the concept of Pirate was a copy of A General History Of Pyrates (attributed to McLaren’s childhood hero Daniel Defoe) acquired at the venerable West End bookshop Foyles.

The Saracen sword flag flown by Captain Thomas Tew was the inspiration for the gold and burgundy Worlds End logo

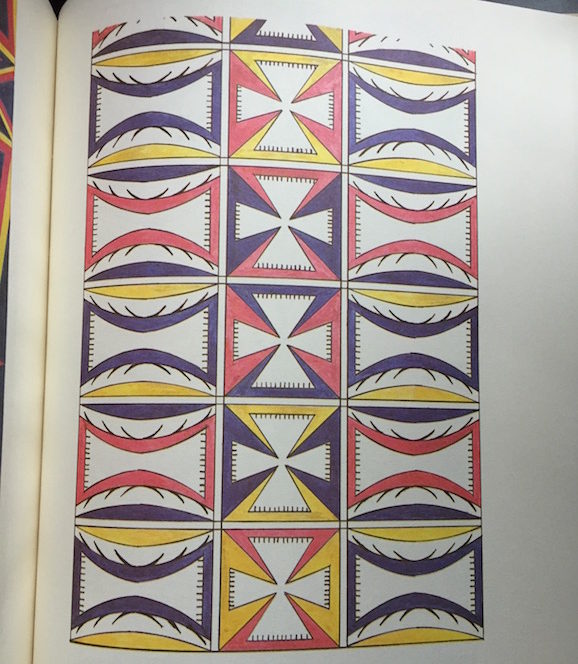

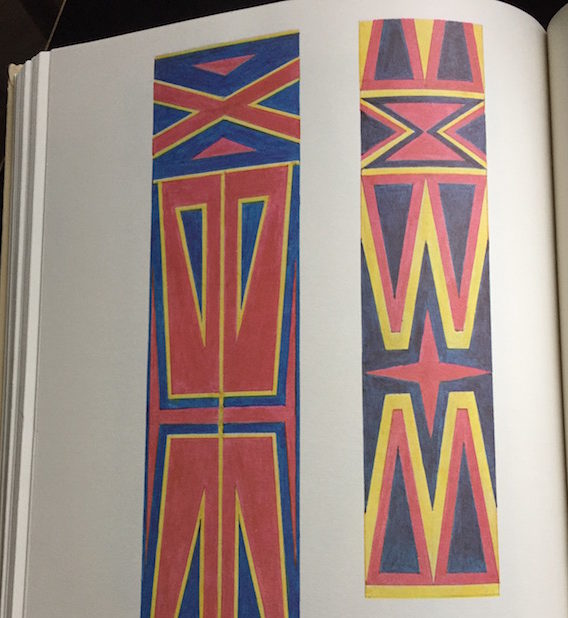

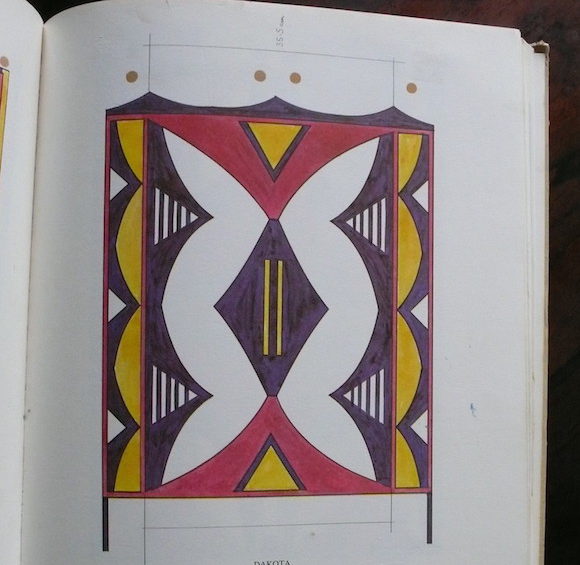

In Indian Rawhide, Mable Morrow’s renditions of the extraordinary tribal designs for parfleches (clothing and bags made from painted hides) provided the bedrock for Savage.

Combined with Westwood’s technical excellence and powers of invention, McLaren’s surprising application of these artworks made Savage a stunning follow-up to Pirate, and set the scene for the development of their fashion vision over the next four collections.

A design by an Oglala woman from the South Pine Reservation, South Dakota appeared across garments in the Savage collection, including these two printed cotton/reverse marl dresses. No reproduction without permission

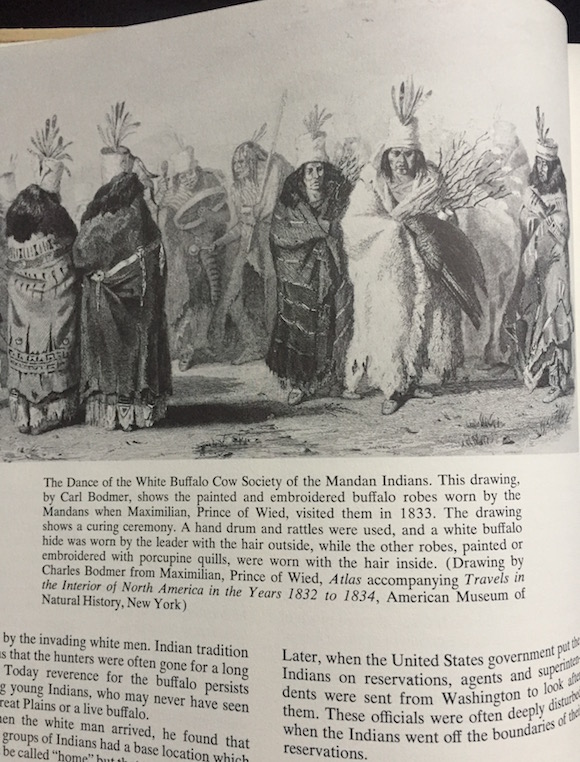

When it was introduced in spring 1982, the follow-up range Nostalgia Of Mud was also known as Buffalo since it incorporated an important theme of Morrow’s book: the talismanic position of the creature among Native American tribespeople.

Morrow included this depiction of the Dance Of The White Buffalo Cow Society of the Mandan showing painted and embroidered buffalo robes

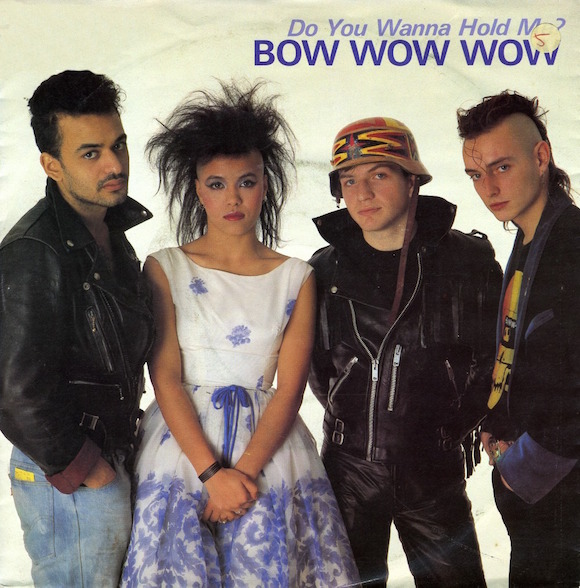

And McLaren ensured that the wild folkloric charm of the Indian Rawhide designs was conveyed by his charges in Bow Wow Wow, some of whom replaced their Pirate clothes with items from Savage when promoting their career during its most successful phase on the back of the hit cover of The Strangeloves’ 1965 song I Want Candy.

Front cover of 1983 Bow Wow Wow single released after McLaren quit managing the group. Design on helmet worn by bass-player Leigh Gorman (second right) combined the cross from the Fox design with the arrowheads from the Pawnee strap

Dakota dress worn by Bow Wow Wow singer Anabella Lwin in Nick Egan-directed I Want Candy video, 1982

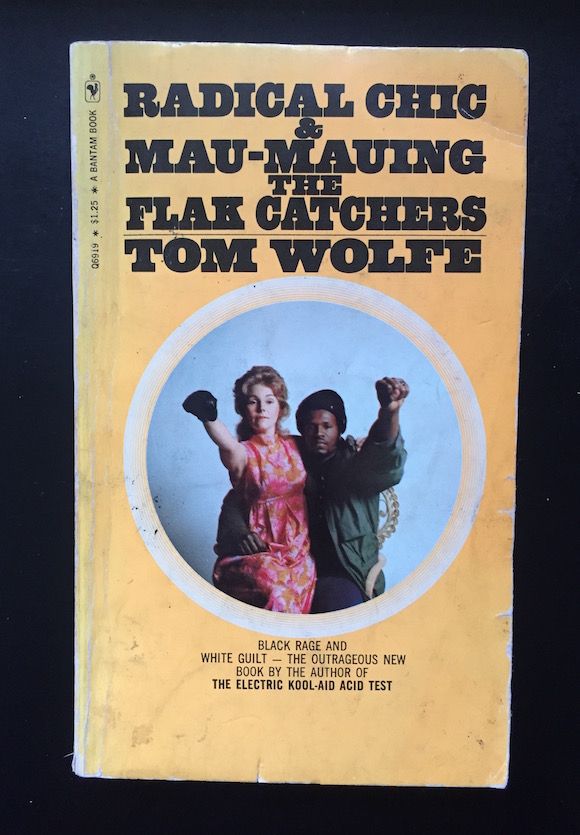

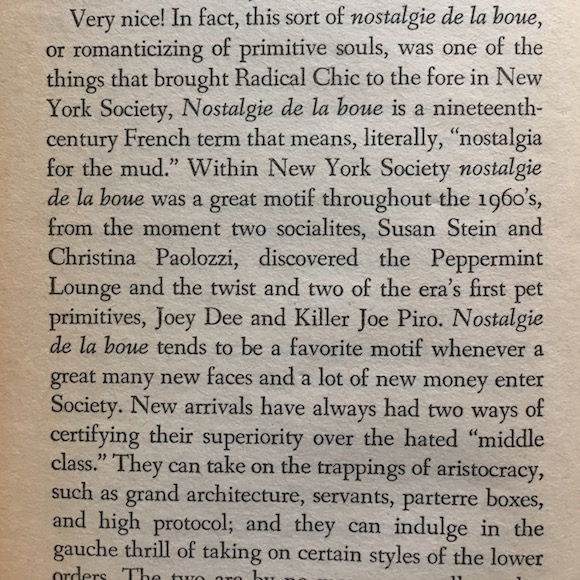

There was a particular literary root for the title of McLaren and Westwood’s collection (and also their offshoot shop in London’s St Christopher’s Place): Nostalgia Of Mud came from a phrase first deployed by Tom Wolfe denoting the “romanticizing of primitive souls” in his 1970 New York magazine article Radical Chic: That Party At Lenny’s. McLaren came across it in an extended essay by Wolfe in his subsequent book Radical Chic & Mau-Mauing The Flak-Catchers.

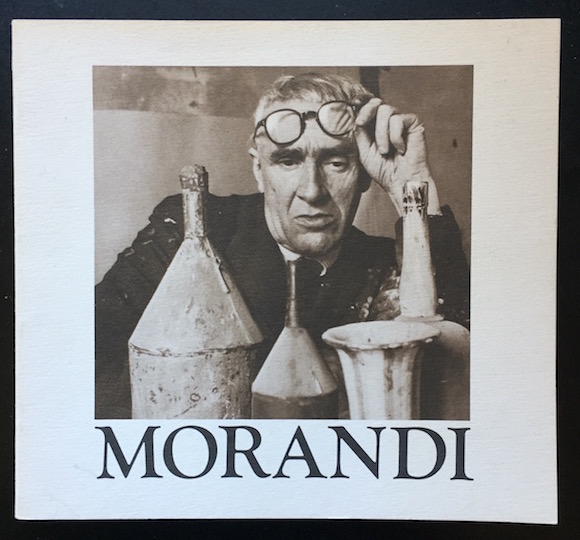

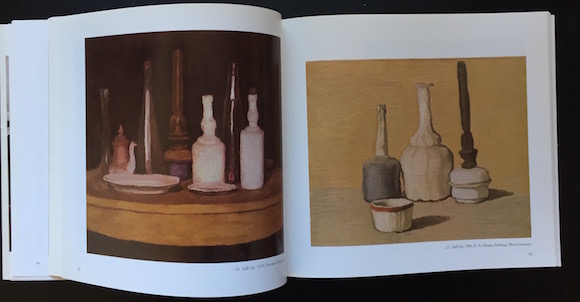

Concept aside, as McLaren revealed in 2004, the earth tones of the Nostalgia Of Mud palette stemmed from a visit to the travelling retrospective of the work of painter Giorgio Morandi staged at New York’s Guggenheim Museum early in 1982.

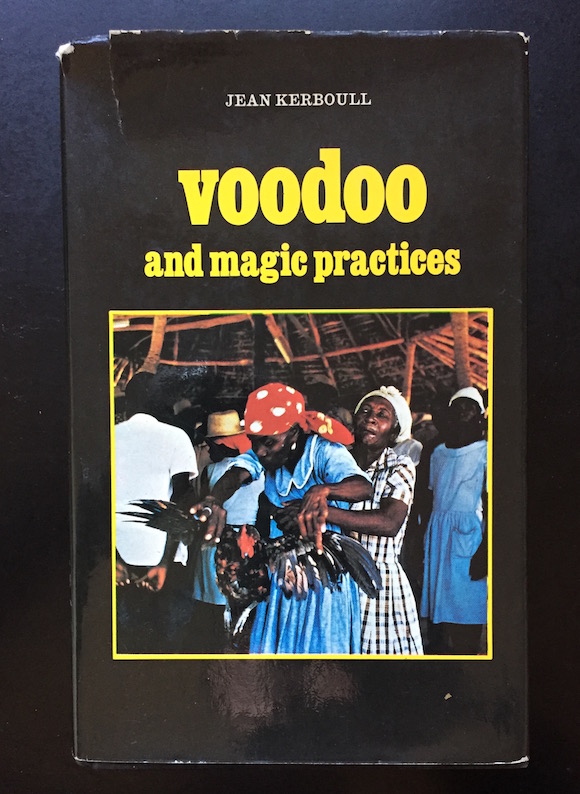

Meanwhile, as I reported recently, McLaren’s concepts for the S/S 1983 collection Witches were triggered by a reading of Jean Kerboull’s book Voodoo And Magic Practices.

In time I’ll revisit McLaren’s literary researches with an exploration of the texts which fired up his final collection with Westwood, Worlds End 1984; this became Hypnos when she struck out on her own that year.

Meanwhile, enjoy these: at 2.40 in this clip McLaren revisits the Guggenheim for the British documentary shown as part of the South Bank Show strand:

And here’s Egan’s Bow Wow Wow video with Anabella Lwin, to use McLaren’s phrase, “dancing in the magic”:

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.